Abstract

This chapter details the intratracheal delivery of dry powder microparticles termed nano-in-microparticles (NIMs) for the purpose of in vivo targeted pulmonary drug delivery. The dry powder NIMs technology improves on previous inhaled chemotherapy platforms designed as liquid formulations. Dry powder microparticles were created through the process of spray drying; a protocol detailing the formulation of NIMs dry powder is included as a separate chapter in this book. Dry powder NIMs containing fluorescent nanoparticles and magnetically-responsive superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles are intratracheally delivered (insufflated) in the presence of a magnetic field and targeted to the left lung of mice. The targeting efficiency of dry powder NIMs is compared to the targeting efficiency of liquid NIMs to demonstrate the superiority of dry power targeting platforms. Targeting is assessed using fluorescence associated with NIMs detected in the mouse trachea, left lung, and right lung by an in vivo imaging system.

Keywords: Dry powder, Nano-in-microparticles, Intratracheal delivery, Insufflation, Superparamagnetism, Iron oxide nanoparticles, Pulmonary delivery, Targeted drug delivery

1. Introduction

1.1. Advantages of Pulmonary Drug Delivery Approach

Pulmonary administration of chemotherapeutics is a direct method of local delivery to the lung, as opposed to indirect methods such as parenteral and oral routes of delivery. Pulmonary drug delivery systems offer many advantages over traditional drug delivery systems [1]. First and foremost, drugs can be delivered regionally instead of systemically, directly to the disease site. Regional delivery allows for a lower drug dose to be used, often resulting in fewer systemic side effects. Also, barriers obstructing therapeutic efficacy are bypassed, such as poor gastrointestinal absorption and first-pass metabolism of drugs in the liver. In addition, pulmonary delivery is noninvasive and “needle-free” allowing for a wide range of substances to be delivered, from small molecules to very large proteins [2]. The lungs have an enormous absorptive surface area (100 m2) and a highly permeable membrane (0.2–0.7 μm thickness) in the alveolar region [3]. Large molecules with low gastrointestinal absorption rates can be absorbed in significant quantities due to the slow mucociliary clearance in the lung periphery resulting in prolonged residence in the lung [4].

Futhermore, inhalable drugs formulated as dry powders have many additional advantages. Dry powders have greater chemical and physical stability compared to aqueous dispersions for nebulization and thus often have increased product shelf lives and may not require refrigeration during storage. A nebulized suspension can prematurely release the drug payload, whereas we have shown that an inhaled dry powder can overcome this limitation in an in vitro setting [5]. Compared to a nebulizer, inhaler devices used to deliver dry powders are more efficient and less time-consuming. This reduces the overall treatment time and improves patient compliance.

1.2. History of Inhaled Chemotherapies

Although the development of inhalational agents for oncological use in humans has been limited [6], there is a large amount of published data regarding aerosol delivery of chemotherapy in preclinical studies. Futhermore feasibility of aerosol delivery has been shown using in vitro models [7, 8], animal models [9-15], and Phase I/II human trials for various cancers [16-20].

In 1968 the chemotherapeutic agent, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), was investigated for inhalational therapy [21]. This study, published by Tatsumura and colleagues, treated patients with inhaled 5-FU preceded by surgery. Study results showed that 5-FU was found in higher concentrations in lung tumors than in the surrounding tissue. In a later study, Tatsumura et al. showed high 5-FU concentrations in the main bronchus and adjacent lymph nodes for nearly 4 h post-administration [18]. Furthermore, the formulation of 5-FU with lipid-coated nanoparticles showed sustained drug release and enhanced anticancer properties [22]. Similarly, Otterson and colleagues evaluated inhaled doxorubicin in a Phase I, and later in a Phase I/II, clinical study and demonstrated the promising efficacy of an aerosol treatment [16, 17]. However, the non-targeted aerosol delivery led to a moderate reduction of pulmonary function and pulmonary dose-limiting toxicity in some patients.

It is therefore critical to target inhaled chemotherapeutics, beyond local delivery, to tumors to protect healthy lung tissue. None of the studies described above used a targeting mechanism within the lung. To this end, Azarmi et al. formulated poly(butylcyanocrylate) nanoparticles with doxorubicin for inhaled, targeted drug delivery to the lung via encapsulation in lactose carrier particles made by spray-freeze drying [23]. This study showed successful in vitro uptake of the nanoparticles into H460 and A549 lung cancer lines through endocytosis rather than passive diffusion. Similarly, Dames et al. used a liquid suspension of magnetically-responsive superparamagnetic iron oxide nano-particles (SPIONs) and plasmid DNA (pDNA) (used as a drug surrogate) to target the different lobes of the lung in mice [11]. Unfortunately, while SPIONs were successful in tissue-targeting, pDNA was found to separate from the SPIONs during pulmonary administration. McBride and colleagues have formulated dry powder nano-in-microparticles (NIMs), incorporating SPIONs and chemotherapeutics in a dry powder lactose matrix that prevented pre-separation of SPIONs and therapeutic while maintaining the size and flow characteristics critical for lung delivery [5]. This formulation platform is detailed in another chapter of this book.

1.3. Micro- and Nanoparticles as Drug Delivery Vehicles

Delivery vehicles (nanoparticles (NPs), microparticles, or nanoparticles encapsulated within microparticles can range in size from several nanometers to a few micrometers. Microparticles intended for inhaled drug delivery should be 1–3 μm in size to achieve alveolar deposition [24]. Depending on the target delivery region, particles exhibit desirable particle size distribution ideally with aerodynamic diameters (da) of 5–10 μm for airways and 1–5 μm for deep lung delivery with a standard density of 1 g/cm3. Particles less than 0.5 μm (NPs) are driven by diffusion and are likely to be exhaled, hence they are often encapsulated and delivered within microparticles.

This chapter describes targeted delivery of dry powder NIMs directly into the lungs of a mouse. NIMs are formulated to be magnetically-responsive, and can be used to target drug payloads to a particular lobe of the lung with the use of an external magnet [5]. NIMs dry powder matrixes have the benefit of physically binding the magnet-targeting SPIONs and drug payload (a fluorescent dye is used as a drug surrogate for visualization). Conversely, NIMs in a liquid suspension run the risk of SPION and drug separation, negating the targeting effect. To compare NIMs dry powder targeting efficiency to NIMs liquid suspension targeting, administration of a liquid suspension to mice using an intratracheal aerosolization device is also described below.

2. Materials

Balb/c mice (6–8 weeks old).

Intubation platform.

Nano-in-Microparticles (NIMs).

Penn Century dry powder Insufflator™.

Neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) permanent cylindrical magnet (grade N52, 22 mm long × 20 mm in diameter).

Laryngoscope.

Mouse intratracheal aerosolizer.

In vivo fluorescence or bioluminescence animal imager.

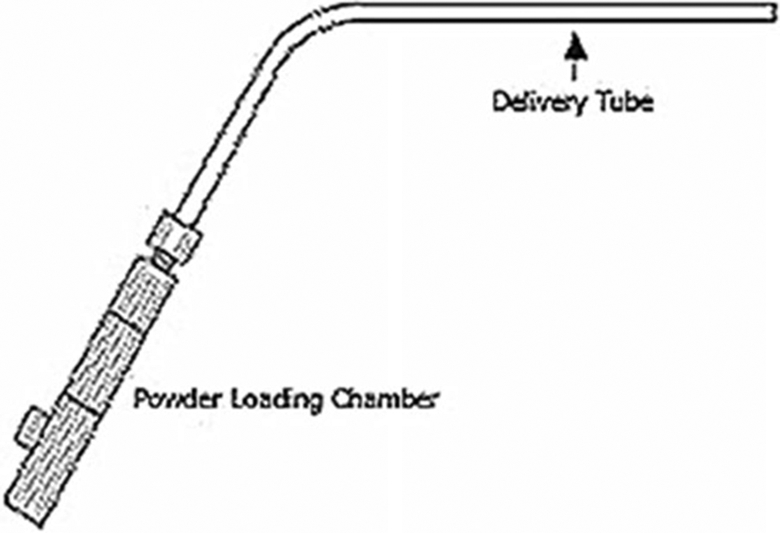

The DP-4M Dry Powder Insufflator™ is specifically developed for pulmonary dry powder administration to mice, and variants suitable for rats, guinea pigs, and larger animals exist (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A dry powder Insufflator™ for mouse (DP-4M). The device consists of a total of three pieces. The dry powder chamber is made up of two pieces; the chamber tube can be pulled apart and loaded with up to 2 mg of dry powder. To close the tube after the powder is loaded into the chamber, the two pieces are gently pressed together with pressure. The third piece of the device is the delivery tube and is attached by a screw thread to the delivery chamber tube. The delivery tube is 8″ in length from the bend angle to the tip of the tube. The insufflation device is fragile and extreme care must be taken to immediately clean the insufflator to prevent clogging. Photo of Dry Powder Insufflator™—Model DP-4 reprinted with permission of Penn-Century, Inc.

3. Methods

3.1. Intratracheal Administration of Dry Powder to Mice

Weigh mouse.

Administer anesthesia (see Note 1).

Weigh the clean insufflator, including the powder chamber and delivery tube. This initial weight will be used to calculate the final amount of powders delivered into the mouse lung.

Add 1–2 mg of dry powder NIMs to the insufflator chamber and close the chamber (see Note 2). Re-weigh the insufflator to ensure the proper powder amount has been loaded into the chamber.

Place the anesthetized mouse supine on the plexiglass intubation platform.

The platform should be situated at a 60° angle facing away from you. The operator will be facing the head of the mouse.

Using the incisor loop (plastic fishing line) hang the front incisors (teeth) of the mouse from the loop. A thin rubber band can then be placed over the mouse to secure the mouse on the intubation platform.

Using a cotton-tipped swab, gently roll the mouse tongue out of its mouth and to one side to expose the oropharynx.

Insert the laryngoscope into the mouth of the mouse. Using the light and blade features, depress the tongue to view the epiglottis. Adding a magnifying glass to the laryngoscope handle (using Velcro) will aid in the clear visualization of the small tracheal opening in a mouse. A white round opening, indicated by the opening and closing of the arytenoid cartilage around the tracheal opening should be visible (see Note 3).

The insufflator delivery tube (cannula) should be inserted down the trachea of the animal, gently proximal to the carina, until the curve of the cannula is positioned at the incisors. Attach the powder loaded chamber of the insufflator to the cannula. A 3 mL disposable plastic syringe is attached to the open end of the insufflator.

With the mouse situated on the plexiglass delivery platform, place the magnet over left lung as the mouse faces away from you, as shown in Fig. 2.

To insufflate the powders, depress the syringe attached to the insufflator with steady, forceful pressure using not more than 500 μL of air (see Note 4).

Note number of puffs given (see Note 5). Reweigh the insufflator after powder delivery (delivery tube and powder chamber) to quantify the amount of dry powder administered to the mouse lung.

If non-significant targeting exists (based on in vivo imaging), surgically open the animal and cut through the skin/ muscle to depth of the rib cage. Surgically expose the left lung by thoracotomy (see Note 6). Then re-place the magnet 1 mm above the incision, with the magnet’s edge perpendicular to the upper section of the left lung. Follow steps 8–13 again to deliver NIMs dry powder using the insufflator.

Sacrifice the mouse immediately. Remove lungs and trachea en bloc and separate (right lung, left lung, and trachea) into distinct tissues for evaluation of targeting efficiency of NIMs to the magnetized lobe. These tissues can be assessed for fluorescence and iron quantification.

Fig. 2.

Targeting NIMs to the left lung during insufflation using a permanent magnet. The mouse has been intubated with the insufflator. A magnet is held over the left lung lobe. NIMs will be dispersed into the lungs when the syringe plunger attached to the insufflator is depressed. NIMs will preferentially target the left lung compared to the right due to the magnetic field

3.2. Measurements to Be Noted

Weight of mouse: ___________________________________ g Theoretical amount of NIMs to be administered to mouse: _________________________________________________ mg Insufflator weight loaded with 2 mg NIMs: _____________ mg Insufflator weight post-NIMs administration: ____________ mg Weight of NIMs administered: ______________ _________ mg Number of insufflator “puffs” given to mouse: ___________ puffs

3.3. Intratracheal Administration of Liquid Suspension to Mice

Weigh mouse.

Administer anesthesia (see Note 1).

Add 1.5 mg NIMs (see Note 2) to 0.5 mL saline and load into the aerosolization device.

With the mouse situated on the intubation platform, place the magnet over the left lung as mouse faces you (see Note 3).

Insert the laryngoscope into the mouth. Using the light and blade features, depress the tongue to view the epiglottis. Adding a magnifying glass to the laryngoscope handle (using Velcro) will aid in the clear visualization of the small tracheal opening in a mouse. You should see a white round opening, indicated by the opening and closing of the arytenoid cartilage around the tracheal opening.

The liquid intratracheal aerosolization device should be inserted the trachea of the animal gently, proximal to the carina, until the curve of the cannula is positioned at the incisors.

To aerosolize the formulation, the plunger should be depressed firmly and with consistent force and speed (see Note 7). Once the plunger has been completely depressed, the liquid suspension will be administered into the mouse lung.

Carefully remove the aerosolizer delivery tube from the mouse trachea.

Sacrifice the mouse immediately. Remove lungs and trachea en bloc and separate (right lung, left lung and trachea) into distinct tissues for NIMs-targeting efficiency to the magnetized. These tissues can be assessed for fluorescence and iron quantification.

3.4. Comparison of Targeting Efficacy

- Evaluate the presence of dye by measuring the fluorescence of each tissue (right lung, left lung, and trachea) (see Notes 8 and 9). Compare targeting efficiency of dye by first calculating NIM-associated fluorescence of each tissue over the total tissue fluorescence. This will tell you the percent ofdye targeted to each tissue, and whether more dye was targeted to the left lung versus the right lung:

- Evaluate the presence of SPIONs by measuring iron content in each tissue (right lung, left lung, and trachea) (see Note 10). Compare targeting efficiency of SPIONs by first calculating the SPION-associated iron content of each tissue over the SPION-associated iron content of the total tissue. This will tell you the percent of SPIONs targeted to each tissue, and whether more SPIONs were targeted to the left lung versus the right lung:

Determine whether the SPIONs separated from the dye during targeting by comparing percentages (dye and SPIONs) for each tissue. The percentage deposited in each tissue will be significantly different if the SPIONs and dye separated during administration.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the University of New Mexico Health Science Center Research and Allocations Committee (RAC) grant. AAM was supported by NSF-IGERT Integrating Nanotechnology with Cell Biology and Neuroscience Fellowship (DGE-0549500) and the NCI Alliance for Nanotechnology in Cancer New Mexico CNTC Training Center. DNP was supported by Bill and Melinda Gates Grand Challenge Exploration (No OPP1061393) and UNM IDIP T32 training grant (T32-A1007538, P.I.– M. Ozbun).

Footnotes

We used 100 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg body weight of ketamine and xylazine by intraperitoneal injection, respectively, for anaesthesia dosing.

Pre-weighing powders into a capsule speeds up the loading process and helps to ensure repeatability when loading similar amounts. For NIMs suspension (liquid) experiments we used the Penn Century Microsprayer® aerosolization device.

Morello et al. has published an excellent synopsis on the insufflation of dry powders into the lung of a mouse [25].

Hoppentocht et al. recently published data stating that 200 μL air volume, as recommended by the manufacturer, did not provide adequate dispersion of the NIMs in the insufflator leading to variable dry powder deposition in mouse lungs [26, 27]. We confirmed this observation and showed that a larger pulsed air volume of 500 μL was required for adequate NIMs dispersion in the lungs using the mouse insufflator. However, a higher air volume may have led to significant powder deposition in the trachea due to inertial impaction.

In our experience, ten puffs administered 25 % of the dry powder NIMs loaded in the insufflator. The remaining 75 % remained in the insufflator. Administering more than ten puffs did not dislodge the remaining NIMs from the insufflator.

A similar surgical protocol to expose the lungs for magnetic targeting is described by Dames et al. [11].

The force used to dispense the NIMs suspension from the liquid intratracheal aerosolization device was maintained at a constant rate.

Significantly more fluorescence (from the dye in the NIMs) was quantified in the trachea for dry powder NIMs than liquid suspension. We attribute this pitfall to the DP-4M insufflator delivery tool. The insufflator deposits the dry powder in the respiratory tract based on firm pushing of the syringe, which is necessary for the proper aerosolization and delivery of NIMs into the lung [25]. However, the high velocity air stream generated by the syringe (attached to the insufflator) leads to powder deposition in the upper conducting airways and the main tracheal bifurcation due to inertial impaction. Dry powder NIMs exiting the insufflator delivery tube had increased momentum and followed their trajectory until they collided with the tracheal wall [25]. NIMs that did not impact the upper respiratory tract were available for magnetic-targeting within the lung lobes. A passive dry powder inhaler that allows slow and deep inspiration may mitigate the upper respiratory tract deposition of NIMs.

For each tissue (right lung, left lung, and trachea), obtain total relative fluorescent units (rfu) as well as region of interest rfus (keeping the region of interest constant for each tissue).

We used Inductively Coupled Plasma–Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES) to determine tissue iron content. However, it is important to note that when using this method you must have a tissue control to subtract out the endogenous iron content of the tissues.

References

- 1.Labiris NR, Dolovich MB (2003) Pulmonary drug delivery. Part I: Physiological factors affecting therapeutic effectiveness of aerosolized medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol 56:588–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolff RK (1998) Safety of inhaled proteins for therapeutic use. J Aerosol Med 11:197–219. doi: 10.1089/jam.1998.11.197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patton JS, Byron PR (2007) Inhaling medicines: delivering drugs to the body through the lungs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6:67–74. doi: 10.1038/nrd2153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agnew JE, Pavia D, Clarke SW (1981) Airways penetration ofinhaled radioaerosol: an index to small airways function? Eur J Respir Dis 62:239–255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McBride AA, Price DN, Lamoureux LR et al. (2013) Preparation and characterization of novel magnetic nano-in-microparticles for site-specific pulmonary drug delivery. Mol Pharm 10:3574–3581. doi: 10.1021/mp3007264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma S, White D, Imondi AR et al. (2001) Development of inhalational agents for oncologic use. J Clin Oncol 19:1839–1847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azarmi S, Tao X, Chen H et al. (2006) Formulation and cytotoxicity of doxorubicin nanoparticles carried by dry powder aerosol particles. Int J Pharm 319:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.03.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tseng C-L, Su W-Y, Yen K-C et al. (2009) The use of biotinylated-EGF-modified gelatin nanoparticle carrier to enhance cisplatin accumulation in cancerous lungs via inhalation. Biomaterials 30:3476–3485. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao R, Markovic S, Anderson P (2003) Aerosol therapy for malignancy involving the lungs. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 3:239–250. doi: 10.2174/1568009033481895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hershey AE, Kurzman ID, Forrest LJ et al. (1999) Inhalation chemotherapy for macroscopic primary or metastatic lung tumors: proof of principle using dogs with spontaneously occurring tumors as a model. Clin Cancer Res 5:2653–2659 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dames P, Gleich B, Flemmer A et al. (2007) Targeted delivery of magnetic aerosol droplets to the lung. Nat Nanotechnol 2:495–499. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasenpusch G, Geiger J, Wagner K et al. (2012) Magnetized aerosols comprising superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles improve targeted drug and gene delivery to the lung. Pharm Res 29:1308–1318. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0682-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gagnadoux F, Hureaux J, Vecellio L et al. (2008) Aerosolized chemotherapy. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 21:61–70. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2007.0656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez CO, Crabbs TA, Wilson DW et al. (2010) Aerosol gemcitabine: preclinical safety and in vivo antitumor activity in osteosarcoma-bearing dogs. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 23:197–206. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2009.0773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yi D, Wiedmann TS (2010) Inhalation adjuvant therapy for lung cancer. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 23:181–187. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2009.0787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otterson GA, Villalona-Calero MA, Sharma S et al. (2007) Phase I study of inhaled Doxorubicin for patients with metastatic tumors to the lungs. Clin Cancer Res 13:1246–1252. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otterson GA, Villalona-Calero MA, Hicks W et al. (2010) Phase I/II study of inhaled doxorubicin combined with platinum-based therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 16:2466–2473. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tatsumura T, Koyama S, Tsujimoto M et al. (1993) Further study of nebulisation chemotherapy, a new chemotherapeutic method in the treatment of lung carcinomas: fundamental and clinical. Br J Cancer 68:1146–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zarogoulidis P, Darwiche K, Krauss L et al. (2013) Inhaled cisplatin deposition and distribution in lymph nodes in stage II lung cancer patients. Future Oncol 9:1307–1313. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemarie E, Vecellio L, Hureaux J et al. (2011) Aerosolized gemcitabine in patients with carcinoma of the lung: feasibility and safety study. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 24:261–270. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2010.0872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tatsumura T, Yamamoto K, Murakami A et al. (1983) New chemotherapeutic method for the treatment of tracheal and bronchial cancers—nebulization chemotherapy. Gan No Rinsho 29:765–770 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hitzman CJ, Elmquist WF, Wattenberg LW, Wiedmann TS (2006) Development of a respirable, sustained release microcarrier for 5-fluorouracil I: in vitro assessment of liposomes, microspheres, and lipid coated nanoparticles. J Pharm Sci 95:1114–1126. doi: 10.1002/jps.20591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azarmi S, Lobenberg R, Roa WH et al. (2008) Formulation and in vivo evaluation of effervescent inhalable carrier particles for pulmonary delivery of nanoparticles. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 34:943–947. doi: 10.1080/03639040802149079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerrity TR, Lee PS, Hass FJ et al. (1979) Calculated deposition of inhaled particles in the airway generations of normal subjects. J Appl Physiol 47:867–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morello M, Krone CL, Dickerson S et al. (2009) Dry-powder pulmonary insufflation in the mouse for application to vaccine or drug studies. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 89:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2009.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoppentocht M, Hoste C, Hagedoorn P et al. (2014) In vitro evaluation of the DP-4M Penn-Century insufflator. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 88:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2014.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duret C, Wauthoz N, Sebti T et al. (2012) Solid dispersions of itraconazole for inhalation with enhanced dissolution, solubility and dispersion properties. Int J Pharm 428:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]