Abstract

Introduction:

Mental health issues during adolescence are common and worsen when financial crisis occur across the world. Identification of mental health needs as they are expressed by adolescents themselves is important for efficient mental health promotion interventions.

Aim:

This systematic review examined studies on the mental health needs among adolescents from their own perspective.

Methods:

Four databases were searched between 2008-2018, starting with 2008 when the global financial crisis began.

Results:

The seven studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria used different data collection methods. Emotional and behavioral problems and hyperactivity were found, while adolescents’ own perceptions also showed positive indicators for mental health. Most studies focus on specific adolescent populations, while the general adolescent population needs more attention as a target group for mental health interventions.

Conclusion:

Interventions should address the needs as they are identified by adolescents in order to promote their mental health. Researchers should develop an instrument which assesses exclusively the adolescents’ mental health needs.

Keywords: Adolescents, mental health, needs, financial crisis, systematic review

1. INTRODUCTION

Globally, 10-20% of children and adolescents experience mental health disorders (1). Similarly, in Europe, more than 10% of children and adolescents have some form of mental health problem (2). In the United States, one in five young people face mental health problems (3). In addition, mental health disorders, such as unipolar depressive disorders, are the first cause of years lost to disability in 10-14 year olds (4). Furthermore, many mental health disorders such as mood disorders, impulse-control disorders, anxiety disorders, substance abuse problems and eating disorders, often begin in adolescence (5). However, about two-thirds of young people do not receive the help they need (6). Untreated mental health problems can have serious consequences such as suicide, which is the third leading cause of death among adolescents (4). Early intervention can prevent significant mental health problems from developing (7). However, opportunities for prevention and early identification of mental health problems are often missed in youth, resulting in the overburdening of the mental health care system (8).

When adolescents’ mental health needs are met, they have a sense of identity and self-worth, sound family and peer relationships, an ability to be productive and to learn, and a capacity to tackle developmental challenges and use cultural resources to maximize growth (9). Thus, awareness of mental health needs among adolescents is limited (10) despite the need to support this population, especially in challenging periods, like an economic crisis (11).

Children, adolescents and young people are among the vulnerable groups, majorly affected by the economic crisis, which influences their mental health (12). The importance of identifying the mental health needs from the perspective of adolescents, especially during the period of economic crisis, lies in the major lifelong health consequences and developmental deficits extreme poverty can cause (13). As far as we are aware, there have been neither systematic reviews nor meta-analyses to date about mental health needs assessment among adolescents for the period of the 2008 financial crisis which spread into a global economic shock (14).

This systematic review examined studies on the mental health needs among adolescents from their own perspective.

2. AIM

The aim of this systematic review is, firstly, to identify the studies that assess mental health needs among adolescents worldwide, secondly, to identify the methods used to assess mental health needs, and finally to present the main study findings of the included studies. The ultimate goals are to raise awareness among mental health professionals about adolescents’ mental health needs and the available assessment tools, and finally, encourage them to implement mental health promotion interventions.

3. METHODS

3.1. Literature search

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) (15). An information specialist assisted search was carried out using four databases (PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, PsycINFO). Search parameters included English-only manuscripts published (or in press) from January 1st 2008 to December 31st 2018. We focused on studies from 2008 onwards, because then was the onset of the global financial crisis, resulted in a dramatic initial economic shock (16) and hit the various Member States to a different degree (17). Some differences between databases and search words used are due to available thesaurus terms in the specific databases, in an attempt to translate the MeSH terms used. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| English language | Language other than English |

| Original, peer-reviewed research articles | Not original, peer-reviewed research articles (e.g. theoretical or methodological papers, systematic reviews, books or book chapters, letters, dissertations, editorials, study protocols, conference papers, validation studies, etc.) or intervention studies |

| Study participants were adolescents (12–18 years), with or without mental health challenges or any potential diagnosis or comorbidity | Study participants were not adolescents as the defined age in the inclusion criteria |

| Mental health needs assessment as reported by adolescents themselves | Mental health needs were assessed or reported by other persons/means than adolescents (e.g. from parents or teachers questionnaires/reports, clinical data, etc.) |

3.2. Study Identification

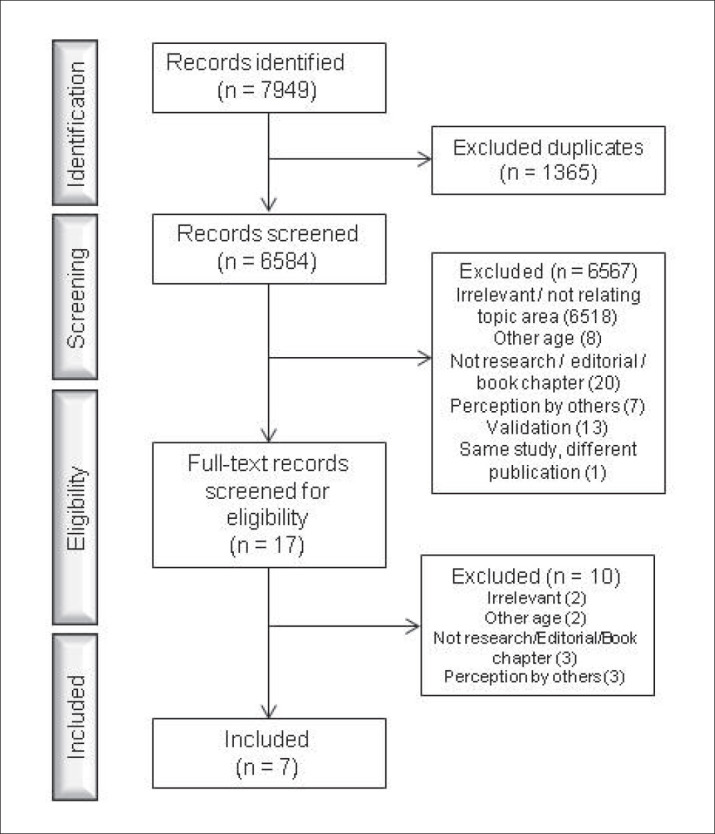

First, all study records were transferred from each database to the reference management service RefWorks (https://refworks.proquest.com/) in order to manage the study records and identify the duplicates. Out of 7949 total records, after duplicates were removed (n=1365), a total of 6584 records remained (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram.

Second, the two reviewers (ES and CA) screened titles and abstracts independently for eligibility; ineligible results were excluded (n=6567). Third, 17 full-text papers were obtained and screened for eligibility by two authors (ES and CA). Additional papers were not identified after a hand search of the reference lists. Finally, seven records satisfied the inclusion criteria. In cases of discrepancy concerning the decisions made between the reviewers, the papers were discussed until a consensus was reached. Figure 1 outlines the search process of the literature.

3.3. Data Extraction and Analyses

First, data were collected on a worksheet in table format. Data from each included study were entered into the data worksheet; each study was treated as a separate case. Descriptive characteristics of the studies were categorized manually. Second, studies’ characteristics were described (authors/year/country of origin, aim of the study, participants involved in the study [age, health status, number], Findings). Third, the assessment of mental health needs was made by identifying methods and instruments used in each study. In addition, reasons for exclusion of studies were presented (Figure 1).

4. RESULTS

4.1. Characteristics of the studies

Seven studies satisfied the inclusion criteria and were assessed. All were published in different journals with different scope and were carried out in different parts of the world. The number of study participants ranged from 34 to 29,352. Even though this literature review focused on adolescents, all studies included different age ranges including children or young adults (Table 2). Only one study focused on the general population (18), the rest of the studies investigated other adolescent population groups; young people in secure facilities (19), orphans (20), with cochlear implants (21), incarcerated (22), those held in custody (23) and from specific ethnic group; American Indians (24).

Table 2. Short description of studies included in the systematic review.

| Study # | Authors (Year) Country | Aim | Participants (age, population group, number) | Method/ instrument and author | Content of instruments/interviews | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | McArdle and Lambie (2018), New Zealand | Describe prevalence of probable mental health disorder and related needs among young people in secure facilities in New Zealand |

13 - 17 yrs (n=204) admitted to a Youth Justice residence |

Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument Version 2 (MAYSI-2). Grisso & Barnum (2006) |

52 items, 7 scales of mental health or behavioural problems: Alcohol/drug use Angry-irritable Depressed-anxious Somatic complaints Suicide ideation Thought disturbance (only for male participants) Traumatic experience |

|

| 2 | Dorsey et al. (2015), Tanzania | Identify mental health problems of children orphaned in the Moshi, Tanzania area who were being cared for in family homes | 7-13 yrs (n=37) with their guardians and “local experts” (n=34) |

|

|

|

| 3 | Duinhof et al. (2015), The Netherlands | Investigate trends in Dutch adolescents; self-reported emotional and behavioral problems between 2003 and 2013 | 11-16 yrs, secondary education (n=29,352) | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Goodman (1977) | Five subscales, each including 5 items scored on a three point Likert scale: Conduct problems Emotional problems Hyperactivity Peer problems Prosocial behaviour, Strengths |

|

| 4 | Anmyr et al. (2012), Sweden | Explore and compare how children with cochlear implants, their parents and their teachers perceive the children’s mental health in terms of emotional and behavioral strengths and difficulties | 9, 12 & 15 yrs with cochlear implants (n=22), their parent (n=22) and their teacher (n=17) | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Goodman (1977) | Five subscales, each including 5 items scored on a three point Likert scale: Conduct problems Emotional problems Hyperactivity Peer problems Prosocial behaviour |

|

| 5 | West et al. (2012), USA | Determine the mental health and service needs of American Indian youth and families in the Chicago area in order to develop culturally-appropriate services to meet these needs | American Indian youth (up to 25 yrs) and families (n=107) | Focus groups | Sample questions from the focus group guide: What are some of the problems that youth in our community face today? What do you hear about mental health services in our community? What would life be like for youth in a healthy family and community? |

|

| 6 | Gretton & Clift (2011), Canada | Identify the prevalence of mental disorders and mental health needs among incarcerated male and female youths in Canada | 12-20 yrs (n=205) |

|

|

|

| 7 | Stathis et al. (2008), Australia | Screen for mental health problems in an Australian adolescent forensic populations, secondly, to assess the usefulness of MAYSI-2 in providing a preliminary assessment of those needs and third, to explore the level of mental health problems in vulnerable populations within detention | 10-17 yrs held in custody (n=402) | Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument Version 2 (MAYSI-2). Grisso & Barnum (2006) | 52 items, 7 scales of mental health or behavioural problems: Alcohol/drug use Angry-irritable Depressed-anxious Somatic complaints Suicide ideation Thought disturbance (only for male participants) Traumatic experience |

|

The assessment of mental health needs was described by various aims in the different studies (Table 2), in terms of describing the prevalence of probable mental health disorder and related needs (19), identifying mental health problems (20) or the trends in emotional and behavioral problems (18), in terms of emotional and behavioral strengths and difficulties (21), determining mental health and service needs (24), identifying the prevalence of mental disorders and mental health needs (22), and screening for mental health problems (23).

4.2. Methods used to assess mental health needs

Most of the studies (n=5) used validated questionnaires (18, 19, 21, 22, 23) while one study (20) included two interviews methods and one used focus groups (24) (Table 3). Two studies used the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (18, 21), three others used the Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument Version 2 (MAYSI-2) (19, 22, 23), while one used in addition the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (DISC-IV) (22). The analysis of the collected data was performed with statistical analyses for the studies using structured, validated tools, and qualitative analyses for the studies which used different qualitative approaches.

4.3. Findings of adolescents’ mental health needs assessment

There is diversity in the findings mainly because the researchers have used different approaches to collect and analyze the data. The main findings are presented in Table 2. Since the assessment of mental health needs was described by various aims in the different studies (Table 2), the findings are presented in terms used by the authors. The studies which used qualitative approaches found that potential mental health-related issues included experiences that negatively impact feelings and behavior such as mistreatment/abuse, discrimination, and isolation, as well as specific emotional and behavioral problems (e.g. stress/over thinking) (20). On the other hand, the study among American Indian youths (24), identified not only the negative but also the positive mental health indicators, with the youths including the need for positive role models, the importance of cultural and spiritual health, positive reinforcement from adults, sense of community, accountability from adults and pride in culture, and they recognized peer pressure as a negative mental health indicator.

There were studies that use the same data collection tools, which help with comparisons and limited conclusions. When mental health needs were assessed with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, researchers could assess the participants’ mental well-being. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire can indicate what decisions to make and what is needed to be done in terms of mental health care. In the Anmyr et al. (21) study almost a quarter rated themselves in a way that indicated mental ill-health (9% borderline and 14% abnormal) on total difficulties and they reported conduct problems (loss of temper, being accused of lying, cheating). Mean levels of conduct problems, emotional problems and peer problems were found rather low by Duinhof et al. (18), while, in Anmyr et al. (21) study complaints of psychosomatic symptoms were not frequent (emotional symptoms), but new situations and many fears offered emotional difficulties for many of the participants. In the same study (21), some of the participants had conduct problems such as anger and loss of temper and they claimed to get on better with adults than with people of their own age (peer problems). Moderate mean levels of hyperactivity were found by Duinhof et al. (18), and Anmyr et al. (21) found that about half of the participants reported difficulties with concentrating and staying still for a long time (hyperactivity-inattention).

The ten-year trends studied by Duinhof et al. (18) showed that emotional and behavioral problem levels of Dutch adolescents were rather stable during 2003-2013. In addition, gender differences were also found to be relatively stable over time with boys reporting more conduct problems and less emotional problems than girls, while in hyperactivity the differences were not substantial at any time point. The studies using the MAYSI-2 to identify mental health needs (19, 22, 23) found high levels of mental health problems. McArdle and Lambie (19) found high levels of mental, emotional and behavioral problems, as well as high rates of problem in drug and alcohol use. Similarly, Gretton and Clift (22) found that substance abuse and dependence disorders were highly prevalent, and aggressive forms of conduct disorder were common, and exposure to physical abuse was common among more than half of the participants while sexual abuse was higher among girls. In regards to gender differences, Gretton and Clift (22) found that female youths had significantly higher odds of presenting with substance abuse and dependence disorders, current suicidal ideation, sexual abuse, PTSD, depression and anxiety symptoms, oppositional defiant disorder and multiple mental disorders diagnoses. On the other hand, males had significantly higher odds of presenting with aggressive symptoms of conduct disorder. The study by Stathis et al. (23) had different results in regards to gender differences; they found that females scored significantly higher than males in being depressed-anxious, somatic complaints and suicidal ideation, while no significant differences were found between genders for alcohol and drug use and angry-irritable scales. McArdle and Lambie (19) found no significant ethnic group differences. Finally, Gretton and Clift (22) who assessed the mental health needs of incarcerated youths found that nearly all participants met the criteria for at least one mental disorder according to DSM-IV (assessed by the DISC-IV).

5. DISCUSSION

The present systematic review aimed to identify studies which assessed mental health needs among adolescents worldwide, focusing on the period since the financial crisis began and describing methods used to assess mental health needs in order to provide useful information for mental health professionals around the world.

Surprisingly, a very small number of original studies aiming to assess the mental health needs among adolescents have been published during the financial crisis period, even though there is a broad consensus (25) about the deleterious consequences of economic crises on mental health. Even though from the year of 2008 is a long time, it was not found any difference in the needs identified in the studies across the world. Although the effect of the financial crisis on the mental health of young people is still unknown, the financial crisis is expected to produce a child and adolescent mental health crisis (26). In addition, many countries in the European Region are facing pressure from the international financial community to reduce health and welfare budgets despite the increased need. Mental health is a vulnerable target of these cuts, as it usually lacks a strong advocacy base to oppose them, unlike physical illnesses (12).

The studies identified in the current systematic review focused on different population groups, with only one (18) assessing the general population’s mental health needs. Thus, it is evident that the studies conducted among adolescents are specifically-focused with limited targets. In regards to the methods used in the different studies, two used interviews and focus group and the other four used standardized questionnaires. The use of validated questionnaires ensured the reliability and validity of the studies (27) and may allow comparisons with other studies when cultural aspects are considered (28). However, none of these questionnaires is developed for assessing mental health needs directly. They have been used as a medium, measuring mental health needs according to the specific aims of each study. It has also been previously noticed that there is no agreement of instruments to be used assessing mental health needs among adolescents (10) and the findings of this review supports this.

The findings are presented using various measures, due to the differing methodology of each study. An issue that needs our attention is that it is not clear in each study how needs were defined as it was seen that mental health “problems” were included in the results of the studies identified by this review. The studies assessed mental health needs in regards to problems or disorders, related to the specific questionnaires, while the studies using a qualitative approach offer an out-of-the-box insight about mental health needs.

More specifically, the qualitative studies included in this review found that potential mental health-related issues included experiences that negatively impact feelings and behavior as well as specific emotional and behavioral problems (20). In a study among 2 to 14 year olds, it was found that nearly half (47.9%) of them had clinically significant emotional or behavioural problems (29). On the other hand, the study among American Indian youths (24), identified not only the negative mental health indicators but also the positive, with the youths including the need for positive role models, the importance of cultural and spiritual health, positive reinforcement from adults, sense of community, accountability from adults and pride in culture, and they recognized peer pressure as a negative mental health indicator.

Different levels of mental health needs were identified by the four studies using questionnaires to assess those needs. Three studies (19, 22, 23) found high levels of mental health problems. In the study by Anmyr et al. (21) almost a quarter of the participants rated themselves in a way that indicated mental ill-health on total difficulties and they reported conduct problems. Mean levels of conduct problems, emotional problems and peer problems were rather low, according to Duinhof et al. (18). Anmyr et al. (21) found that complaints of psychosomatic symptoms were not frequent (emotional symptoms), but new situations and many fears offered emotional difficulties for many of the participants. In the same study (21), some of the participants had conduct problems such as anger and loss of temper and they claimed to get on better with adults than with people of their own age (peer problems).

An earlier study among 5 to 15 year olds identified over 70% as having conduct, hyperactivity, depressive and some anxiety disorders (30). Moreover, it is found that the mental health needs of looked after children are significantly higher than those of the general population (31). In a study among looked after children aged 11-18 years, 25% had a probable conduct disorder, 6% a probable emotional disorder and 2% a probable hyperactivity disorder (32). Another study (33) found that 44% of children in foster care are identified to have emotional needs. Moderate mean levels of hyperactivity were found in the current systematic review by Duinhof et al. (18), and (21) found that about half of the participants reported difficulties with concentrating and staying still for a long time (hyperactivity-inattention). A later study aiming to determine the prevalence of emotional and behavioural problems among Iranian 6-18 year olds found that attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (11.9%) was the most common disorder (34). In addition, hyperactivity and inattention are self-reported more often than other behavioural or emotional difficulties among adolescents in some Nordic countries (28).

On the other hand, in studies that assess mental health needs reported by parent or teachers, different results are seen as compared to the self-reported studies. In a study among parents of 16/17 year olds, 29% parents of them reported that their child needed help for mental problems (35). Similarly, a mental health need was reported in 65 children (28.5 % of the sample) by mothers or teachers among Latino children of immigrants and most (76.9 %) of these received no services (36). It has been found that teachers and parents may overestimate mental health needs as was the case in a study in the UK of 11–16 year olds; higher than average levels of need were identified, with teachers reporting that 18% of pupils scored abnormally on the SDQ, and parent rates were also higher than the national average at 13.4% (37). In a study among children under 12, findings from the parents reports indicated a high prevalence of mental health problems, with 81 % of the children in the sample having a total difficulties score in the borderline or abnormal range and 90 % of the children having borderline or abnormal scores on at least one of the subscales (conduct, emotional, peer or attention problems) (38). In a study among Iranian children and adolescents, the results of the parents reports’ revealed 21.4% with emotional problems, 32.9% with conduct problems, 20% with hyperactivity, 25.6% with peer problems, 7.6% with problems in prosocial behaviors and 16.7% with total difficulties. Emotional problems were more prevalent among girls, while conduct problems, hyperactivity, total difficulties and problems in prosocial behaviors were more prevalent among boys. Higher educational level of parents was a protective factor against some psychological problems (39).

Finally, Gretton and Clift (22) who assessed the mental health needs of incarcerated youths found that nearly all participants met the criteria for at least one mental disorder according to DSM-IV. While, an Australian study (40) identified 14% of 4-17 years olds as having mental health problems, while among the general population (13 to 19 year olds) (41) the overall prevalence for anxiety, behaviour or depressive disorders was found 29%.

A possible limitation of our systematic review is that there is no heterogeneity in the designs and the measures used to assess mental health needs in the different studies, thus a meta-analysis was not possible. Therefore, this review cannot lead to generalizations of the outcomes. However, different tools are identified and useful information is provided in regards to mental health assessments among adolescents for the multidisciplinary teams working towards mental health. In addition, including only English language studies might have resulted in excluding relevant studies published in other languages.

6. CONCLUSION

As it is revealed from this review, even though mental health has been of an important public health aspect, there is a gap that researchers need to fill in. Moreover, the current literature review clearly shows that there are mental health needs among adolescents which need to be addressed. Mental health professionals should plan and implement mental health promotion interventions. Finally, evaluation is needed in order to improve those interventions and since not specific tools have been identified by the current review of the literature, future research should focus on the development of measurement tools designed specifically for assessing the mental health needs among adolescents.

Author’s contribution:

Each author gave substantial contribution to the conception or design of the work and in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work. Each author had role in drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Each author gave final approval of the version to be published and they agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflicts of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship:

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. Adolescents and mental health. 2017. [28. 6. 2020]. Available at URL: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/mental_health/en/

- 2.European Public Health Alliance. Growing up in the unhappy shadow of the economic crisis: Mental health and well-being of the European child and adolescent population. 2014. [28. 6. 2020]. Available at URL: http://v3.epha.org/IMG/pdf/_EPHA_Report_Mental_Health_Child_and_Adolescent_Population_Economic_Crisis.pdf.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mental Health Surveillance among Children - United States, 2005 - 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62. 2013. [28. 6. 2020]. pp. 1–35. Available at URL: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6202a1.htm.

- 4.WHO. Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health: Adolescent health epidemiology. 2012. [28. 6. 2020]. Available at URL: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/epidemiology/adolescence/en/

- 5.Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aquilar-Gaxioka S, Alonso J, Lee S, Üstun TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(4):359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein ME, et al. Service Utilization for Lifetime Mental Disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian Policy Brief. Childhood mental health: promotion, prevention, and early intervention. No 5. 2006. [28. 6. 2020]. Available at URL: http://www.rch.org.au/uploadedFiles/Main/Content/ccch/PB5_Childhood_mental_health.pdf. http://www.rch.org.au/uploadedFiles/Main/Content/ccch/PB5_Childhood_mental_health.pdf. Accessed: 28. 6. 2020.

- 8.Knitzer J, Cooper J. Beyond integration: challenges for children’s mental health. Health Aff. 2006;25(3):670–679. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. Child and adolescent mental health policies and plans. 2005. 2005. [28. 6. 2020]. Available at URL: http://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/services/9_child%20ado_WEB_07.pdf.

- 10.WHO. Adolescents’ mental health. Mapping actions of nongovernmental organizations and other international development organizations. 2012. [28. 6. 2020]. Available at URL: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/adolescent_mental_health/en/

- 11.Anagnostopoulos DC, Soumaki E. The state of child and adolescent psychiatry in Greece during the international financial crisis: A brief report. Eur Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;22(2):131–134. doi: 10.1007/s00787-013-0377-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO. Impact of economic crises on mental health. 2011. [28. 6. 2020]. Available at URL: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/134999/e94837.pdf.

- 13.Shonkoff J, Phillips D, editors. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin CYY, Edvinsson L, Chen J, Beding T. New York: Springer; 2013. National Intellectual Capital and the Financial Crisis in Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan. 2013. [28. 6. 2020]. Available at URL: http://www.who.int/entity/mental_health/publications/action_plan/en/index.html.

- 17.European Commission. Economic Crisis in Europe: causes, consequences and responses. 2009. [28. 6. 2020]. Available at URL: http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/ publication15887_en.pdf 02.07.2017.

- 18.Duinhof EL, Stevens GW, van Dorsselaer S, Monshouwer K, Vollebergh WA. Ten-year trends in adolescents’ self-reported emotional and behavioral problems in the Netherlands. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(9):1119–1128. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0664-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McArdle S, Lambie I. Screening for mental health needs of New Zealand youth in secure care facilities using the MAYSI-2. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2018;28:239–254. doi: 10.1002/cbm.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorsey S, Lucid L, Murray L, et al. A qualitative study of mental health problems among orphaned children and adolescents in Tanzania. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(11):864–870. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anmyr L, Larsson K, Olsson M, Freijd A. Strengths and difficulties in children with cochlear implants - comparing self-reports with reports from parents and teachers. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76(8):1107–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gretton HM, Clift JWC. The mental health needs of incarcerated youth in British Columbia, Canada. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2011;34(2):109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stathis S, Letters P, Doolan I, et al. Use of the Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument to assess mental health problems in young people within an Australian youth detention centre. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008;44(7-8):438–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2008.01324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West AE, Williams E, Suzukovich E, Strangeman K, Novins D. A Mental Health Needs Assessment of Urban American Indian Youth and Families. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;49(3-4):441–453. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9474-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin-Carrasco M, Evans-Lacko S, Dom G, et al. EPA guidance on mental health and economic crises in Europe. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;266(2):89–124. doi: 10.1007/s00406-016-0681-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolaitis G, Giannakopoulos G. Greek financial crisis and child mental health. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):335. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimberlin CL, Winterstein AG. Validity and reliability of measurement instruments used in research. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(23):2276–2284. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obel C, Heiervang E, Rodriguez A, et al. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in the Nordic countries. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;13(suppl. 2):ii32–ii39. doi: 10.1007/s00787-004-2006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Wagner HR, et al. Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: a national survey. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):960–970. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodman R, Ford T, Simmons H, Gatward R, Meltzer H. Using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:534–539. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richards L, Wood N, Ruiz-Calzada L. The mental health needs of looked after children in a local authority permanent placement team and the value of the Goodman SDQ. Adopt Foster. 2006;30(2):43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck A. Addressing the mental health needs of looked after children who move placement frequently. Adopt Foster. 2006;30(3):60–65. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan DJ, van Zyl M.A. The well-being of children in foster care: Exploring physical and mental health needs. Children Youth Serv Rev. 2008;30(7):774–786. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dodangi N, Ashtiani NH, Valadbeigi B. Prevalence of DSM-IV TR Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents of Paveh, a Western City of Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(7):e16743. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.16743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jansen DEMC, Wiegersma P, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Vollebergh WAM, Reijneveld SA. Need for mental health care in adolescents and its determinants: The TRAILS Study. Eur J Public Health. 2012;23(2):236–241. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks087. (2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toppelberg CO, Hollinshead MO, Collins BA, Nieto-Castañon A. Cross-sectional study of unmet mental health need in 5- to 7-year old latino children in the united states: do teachers and parents make a difference in service utilization? School Ment Health. 2013;5(2):59–69. doi: 10.1007/s12310-012-9089-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hackett L, Theodosiou L, Robson C, Spicer F, Lever R. Understanding the mental health needs of secondary school children in Manchester. Ment Health Fam Med. 2011;8(3):173–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitted KS, Delavega E, Lennon-Dearing R. The youngest victims of violence: examining the mental health needs of young children who are involved in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2013;30(3):181–195. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohammadi MR, Salmanian M, Ghanizadeh A, et al. Psychological problems of Iranian children and adolescents: parent report form of Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. J Ment Health. 2014;23(6):287–291. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2014.924049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sawyer MG, Arney FM, Baghurst PA, et al. The mental health of young people in Australia: key findings from the child and adolescent component of the national survey of mental health and well-being. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(6):806–814. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts N, Stuart H, Lam M. High School Mental Health Survey: Assessment of a Mental Health Screen. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53(5):314–322. doi: 10.1177/070674370805300506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]