Abstract

Backgrounds

Patients at greatest risk of severe clinical conditions from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and death are elderly and comorbid patients. Increased levels of cardiac troponins identify patients with poor outcome. The present study aimed to describe the clinical characteristics and outcomes of a cohort of Italian inpatients, admitted to a medical COVID-19 Unit, and to investigate the relative role of cardiac injury on in-hospital mortality.

Methods and results

We analyzed all consecutive patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 referred to our dedicated medical Unit between February 26th and March 31st 2020. Patients’ clinical data including comorbidities, laboratory values, and outcomes were collected. Predictors of in-hospital mortality were investigated. A mediation analysis was performed to identify the potential mediators in the relationship between cardiac injury and mortality. A total of 109 COVID-19 inpatients (female 36%, median age 71 years) were included. During in-hospital stay, 20 patients (18%) died and, compared with survivors, these patients were older, had more comorbidities defined by Charlson comorbidity index ≥ 3(65% vs 24%, p = 0.001), and higher levels of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (Hs-cTnI), both at first evaluation and peak levels. A dose–response curve between Hs-cTnI and in-hospital mortality risk up to 200 ng/L was detected. Hs-cTnI, chronic kidney disease, and chronic coronary artery disease mediated most of the risk of in-hospital death, with Hs-cTnI mediating 25% of such effect. Smaller effects were observed for age, lactic dehydrogenase, and d-dimer.

Conclusions

In this cohort of elderly and comorbid COVID-19 patients, elevated Hs-cTnI levels were the most important and independent mediators of in-hospital mortality.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11739-020-02495-w) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Coronavirus 2019, COVID-19, Cardiac injury, Cardiac troponin

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection shows fast contagiousness and a high rate of morbidity and mortality [1–4]. Italian public healthcare systems have been overwhelmed by infected people, forcing clinicians to tough decisions for rationing medical care [5, 6]. Assessing the severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is crucial for a correct triage and prioritization. From published experiences, the patients at greatest risk of serious illness of COVID-19 and death are elderly comorbid patients, particularly those with cardiovascular diseases [7–10]. Cardiac injury, demonstrated by the rise of high-sensitivity cardiac troponins is a common finding in patients with severe COVID-19 and previous reports pointed it as a strong predictor of adverse outcome [9–12]. Such observations may justify considering other pathogenetic mechanisms of myocardial damage, beyond the direct viral infection of the myocardium by SARS-CoV-2. Either the concomitant presence of the cytokines storm and the pneumonia-related hypoxia could also determine myocardial ischemia, by altering the myocardial oxygen supply–demand balance. The concerted negative effects of these events, along with underlying coronary artery disease (CAD), can explain the cardiac troponins elevation. However, little is known about the clinical significance of cardiac injury in non-critically ill COVID-19 patients. Furthermore, the link between cardiac injury and mortality is unclear: specifically, it is not known whether there is a direct effect of cardiac injury on mortality or whether this effect is mediated by the underlying comorbid conditions.

Therefore, the aims of the present study are (1) to describe the clinical characteristics, the incidence of cardiac injury and outcomes of a cohort of Italian COVID-19 patients, admitted to our medical non-intensive COVID-19 Unit, (2) to perform a post-hoc exploratory mediation analysis to identify the extent to which the cardiac injury mediates in-hospital mortality.

Methods

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will be available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure on reasonable request.

This was a single-center, observational study enrolled all consecutive patients with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and clinical and radiological signs of COVID-19, referred from the Emergency Department to our medical, non-intensive COVID-19 Unit of Azienda Ospedaliera Padova (Italy), between February 26th and March 31st 2020. Criteria for referral to our Unit was the no-need, or no-eligibility for age or comorbidities, of mechanical or non-invasive ventilation. Patients without laboratory cardiac troponins evaluation were excluded from the study.

According to the WHO guidance (13), laboratory confirmation for SARS-CoV-2 was defined as a positive result of real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay of nasal and pharyngeal swabs.

Study data and clinical information were collected and managed by medical staff using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at University of Padova [14, 15].

All clinical investigations were conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki (2001). Verbal consent from patients for management of personal data was obtained. The study protocol was approved by the cardiovascular section inhouse Ethics Committee on Human Research of the Padova Province.

Data collection

Clinical patient data reported in this study included the following: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), clinical parameters on admission in the Emergency Room, comorbidities including hypertension, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, chronic CAD, chronic heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral atheromasia, chronic pulmonary- kidney-liver disease, solid malignancy, leukemia, lymphoma, dementia, connective tissue disease and acquired immunodeficiency disease. Charlson Comorbidity Index, a score widely used in epidemiological studies to predict length of hospitalization, health-resources use, and 1-year mortality, was calculated [16]. Laboratory examinations on admission and the maximum value during the hospitalization were reported. In particular, the high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (Hs-cTnI) assay was based on the immunometric method with chemiluminescence detection and patients were considered to have acute cardiac injury if serum levels Hs-cTnI were above the 99th percentile upper reference limit (32 ng/L for males, 16 ng/L for females). Electrocardiography and echocardiography data were not object of analysis in this work. Cardiac imaging diagnostic techniques requiring the transportation of COVID-19 patients in other areas of the hospital and all cardiac catheterization laboratory procedures were discouraged to minimize the risk of dissemination and staff exposure, and performed only if considered decisive for the patient management or lifesaving, according to scientific consensus statements [17, 18].

Outcome

The endpoint was incidence of COVID-19 associated in-hospital mortality. The number of patients discharged, and referred to intensive care unit (ICU), and still admitted on April the 1st 2020, was also determined. Discharge criteria were: (1) relieved clinical symptoms, (2) normal body temperature, (3) complete weaning from oxygen therapy maintained for 48 h, (4) resolution of inflammation as shown by chest radiography and blood tests, (5) no evidence of arterial oxygen desaturation on six-minute walk test.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were carried out for all clinical variables. Data are presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]) for continuous variables and as percentages (absolute numbers) for categorical variables. To compare differences between survivors and non-survivors, we used the Mann–Whitney U test, Chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

A two-sided p of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Cardiac injury effect on in-hospital mortality was evaluated using a Generalized Additive Model with logit link and restricted cubic splines to allow for non-linearities [19]. Potential mediators of the link between cardiac injury and mortality were explored using a mediation analysis [20]. Both mediation and outcome models were built using an exhaustive search approach among all variables considered in the dataset using the Bayesian Information Criterion [21]. All confidence intervals (CIs) have been computed using bias-adjusted bootstrap with 10,000 runs. We used the Somer’s Dxy as a measure of goodness of fit (the closer to 1 the better) to present results of the multivariable model for outcome. Analyses were conducted using the R System [22], with mediation [23] and glmulti [24] libraries.

Results

Baseline characteristics

During the study period, 136 patients were admitted to our Medical Unit for COVID-19. Patients with missing Hs-cTnI results (n = 27) were excluded. The study population included 109 patients (female n = 36, 33%), with a median age was 71 years (IQR 60–81), and a BMI 28 kg/m2 [24–30]. During the observation period, 20 (18%) patients died, 83 (76%) patients were discharged, 6 (5.5%) were still hospitalized. The median length of stay was 11 days (IQR 6–16).

Hypertension (68 patients, 62%), dyslipidemia (39, 36%) and diabetes mellitus (27, 25%) were the most common cardiovascular risk factors. No current smokers were identified, past smokers were 26 (24%). Chronic CAD, chronic heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease were known in 18 patients (17%), 16 (15%), 17 (16%), and 13 (12%), respectively. Charlson Comorbidity Index was 0 in 36 (33%), 1–2 in 39 (36%), > 3 in 34 (16%). Other comorbidities, as well as admission parameters, symptoms, home therapy and clinical management are reported in Supplemental Files.

Compared with the survivors, non-survivors were significantly older (86 vs 69 years, p < 0.001), more likely to have hypertension (80% vs 58%, p = 0.050), dyslipidemia (55% vs 32%, p = 0.047), chronic kidney disease (30% vs 8%, p = 0.014), chronic CAD (45% vs 9%, p = 0.001) and higher Charlson Comorbidity Index values (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with COVID-19

| COVID-19 | Alive | Dead | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 109 | n = 89 | n = 20 | ||

| Age (years) | 71 (60–81) | 69 (57–79) | 86 (77–87) | < 0.001 |

| Female sex | 36 (33) | 26 (29) | 10 (50) | 0.074 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28 (24–31) | 28 (25–31) | 22 (19–31) | 0.071 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 68 (62) | 52 (58) | 16 (80) | 0.050 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 27 (25) | 21 (24) | 6 (30) | 0.572 |

| Complicated diabetes | 16 (15) | 5 (8) | 11 (24) | 0.020 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 39 (36) | 28 (32) | 11(55) | 0.047 |

| Smoking history | 26 (24) | 20 (23) | 6 (30) | 0.475 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 13 (12) | 7 (8) | 6 (30) | 0.014 |

| Chronic liver disease | 7 (6) | 7 (8) | 0 | 0.345 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 17 (16) | 12 (14) | 5 (25) | 0.302 |

| Chronic heart failure | 16 (15) | 11(12) | 5 (25) | 0.167 |

| Chronic CAD | 18 (17) | 9 (10) | 9 (45) | 0.001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥ 3 | 34 (31) | 21 (24) | 13 (65) | 0.001 |

| Admission laboratory findings | ||||

| Hs-cTnI (ng/L) | 17.0 (5.0–54.0) | 6.0 (3.0–14.0) | 64.0 (36.0–133) | < 0.001 |

| Abnormal Hs-cTnI | 41 (38) | 23 (26) | 18 (90) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 128 (122–140) | 129 (123–143) | 124 (116–131) | 0.111 |

| Lymphocytes (× 109/L) | 0.97 (0.70–1.33) | 1.07 (0.73–1.38) | 0.66 (0.40–1.05) | 0.079 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 73 (37–120) | 58 (30–118) | 101 (80–161) | 0.006 |

| d-Dimer (µg/L) | 275 (158–784) | 230 (150–575) | 773 (336–1711) | 0.003 |

| LDH (U/L) | 326 (249–406) | 304 (245–381) | 405 (294–670) | 0.008 |

| Peak laboratory findings | ||||

| Hs-cTnI (ng/L) | 18.0 (7.0–96.0) | 16.0 (6.0–37.0) | 279 (48–1084) | < 0.001 |

| Abnormal Hs-cTnI | 46 (42) | 28 (32) | 18 (90) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.1 (9.60–12.6) | 11.2 (9.8–12.6) | 10.9 (8.1–12.5) | 0.320 |

| Lymphocytes (× 109/L) | 0.70 (0.50–1.00) | 0.80 (0.50–1.10) | 0.45 (0.20–0.75) | 0.002 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 130 (87–200) | 120 (74–170) | 185 (110–251) | 0.045 |

| d-Dimer (µg/L) | 901 (361–2883) | 580 (293–2106) | 2846 (1092–4029) | 0.003 |

| LDH (U/L) | 397 (317–580) | 366 (294–517) | 630 (484–1098) | < 0.001 |

| Serum ferritin (µg/L) | 1225 (667–2311) | 1070 (665–1978) | 2663 (756–4701) | 0.035 |

| BNP (ng/L) | 90 (22–262) | 70 (20–190) | 210 (98–351) | 0.034 |

| IL-6 (ng/L) | 48 (15–115) | 40 (11.8–95) | 164 (56–298) | 0.028 |

| Outcome | ||||

| Length of stay (days) | 11 (6–16) | 12 (6–17) | 8 (4–14) | 0.129 |

| Referred to ICU | 31 (30) | |||

| Death | 20 (18) | |||

| Still hospitalized | 6 (5.5) | |||

| Discharged | 83 (76) | |||

Categorical variables are presented as number of patients (%). Continuous values are expressed as median with 25% and 75%-iles

Abnormal Hs-cTnI was defined when ≥ 32 ng/L for males, ≥ 16 ng/L for females

BMI body mass index, CAD coronary artery disease, Hs-cTnI high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I, CRP C-reactive protein, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, BNP brain natriuretic peptide, IL-6 interleukin-6, ICU intensive care unit

Laboratory value

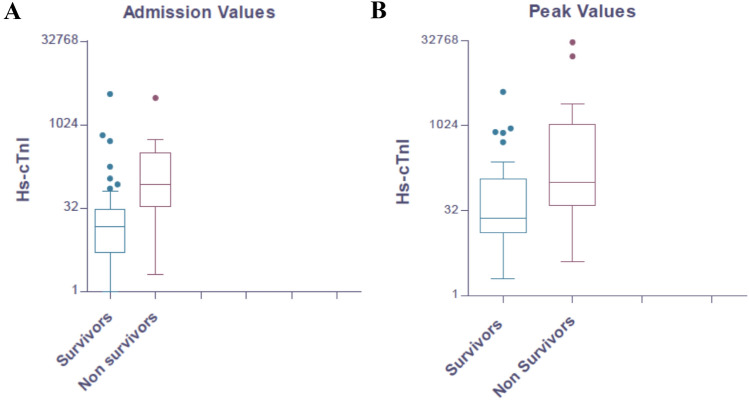

On admission, abnormal median values of hemoglobin, lymphocytes, C-reactive protein (CRP), d-Dimer and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were recorded. Hs-cTnI levels were out of normality ranges in 41 (38%). Compared with survivors, non-survivors presented with higher median levels of Hs-cTnI (64 vs 6 ng/L, p < 0.001; abnormal in 90% vs 30%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1a), CRP (101 vs 58 mg/L, p = 0.006), d-Dimer (773 vs 230 µg/L, p = 0.003) and LDH (405 vs 304 U/L, p = 0.008). During the hospitalization, almost the same trend was observed, with non-survivors showing higher levels of peak Hs-cTnI (279 vs 16 ng/L, p < 0.001; abnormal in 90% vs 32%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1b), lymphocytes (0.45 vs 0.80 × 109/L, p = 0.002), CRP (185 vs 20 mg/L, p = 0.045), d-Dimer (2846 vs 580 µg/L, p = 0.003), LDH (630 vs 366 U/L, p < 0.001). Also, serum ferritin (2663 vs 1070 µg/L, p = 0.035), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (210 vs 70 ng/L, p = 0.034) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (164 vs 40 ng/L, p = 0.028) were higher in non-survivors, compared with survivors.

Fig. 1.

Levels of admission and peak Hs-cTnI in our cohort of COVID-19 patients. Compared with survivors, non-survivors presented higher median levels of Hs-cTnI both on admission (64 vs 6 ng/L, p < 0.001) (a) and peak levels during the hospitalization (279 vs 16 ng/L, p < 0.001) (b)

Cardiac injury effect on in-hospital mortality

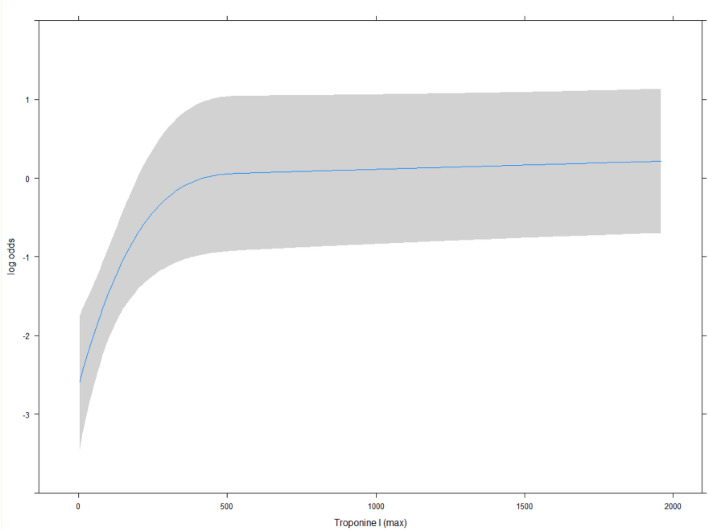

Figure 2 indicates the effect of peak Hs-cTnI on mortality: a non-linear effect (p < 0.001) of Hs-cTnI levels on in-hospital mortality was observed from 0 to 200 ng/L [OR 6.92 (95% CI 2.39–19.99)].

Fig. 2.

Effect of peak Hs-cTnI on mortality. Non-linear effect (p < 0.001) of Hs-cTnI from 0 to 200 ng/L is to increase risk of death by odds ratio (OR) 6.92 (95% CI 2.39–19.99). Curvature changes to a plateau at 209.18 ng/L (95% CI 110.80–365.75)

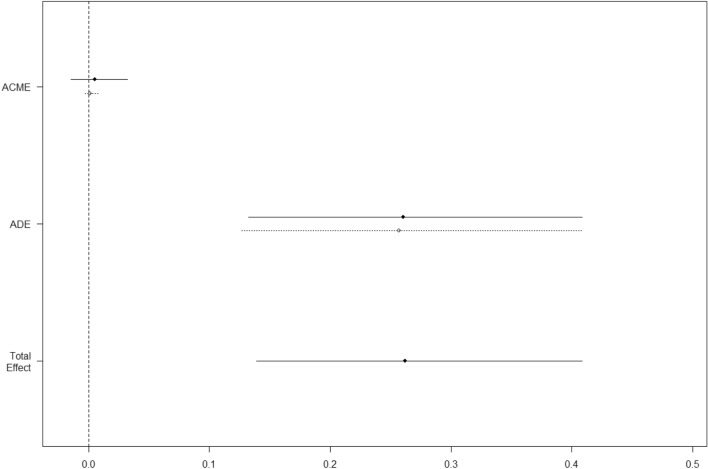

Table 2 reports the relative effect of each predictor as a mediator on in-hospital mortality as evaluated at multivariate mediation analysis: as it can be seen the strongest mediator of in-hospital mortality was peak Hs-cTnI, followed by chronic kidney disease, and chronic CAD. These three factors led to a proportion mediated of 70%. The addition of LDH increased the proportion mediated to 89%. The independent predictive effect of Hs-cTnI is further supported by the multivariate model for mortality with an OR of 32.58 (Table 3). We then performed an additional analysis to assess whether the peak of Hs-cTnI was either mediated or direct. Figure 3 shows that a statistically significant effect of the average direct effect: this testifies a direct effect of peak Hs-cTnI on mortality, with no significant interaction with other confounders.

Table 2.

Mediation analysis of risk of death in patients with COVID-19

| Effect | 95% | CI | p value | ME (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal Hs-cTnI | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.39 | 0.004 | 0.57 |

| Female sex | 0.09 | − 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 6.98 |

| Age > 70 years | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.048 | 0.51 |

| Hypertension | 0.04 | − 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.462 | 3.21 |

| Diabetes | 0.06 | − 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.376 | 4.67 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.08 | − 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.224 | 3.72 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.52 | 0.044 | 0.00 |

| Chronic CAD | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.022 | 0.60 |

| Heart failure | 0.00 | − 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.88 | 18.17 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥ 3 | 0.09 | − 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 4.52 |

| P/F < 100 | − 0.11 | − 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.108 | 5.32 |

| LDH | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 0.012 | 1.21 |

| d-Dimer | 0.14 | − 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.058 | 2.64 |

| Serum ferritin | − 0.06 | − 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.374 | 0.57 |

| BNP | 0.08 | − 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.216 | 5.87 |

| Lymphocytes | − 0.14 | − 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.048 | 1.96 |

| Hemoglobin | − 0.03 | − 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.684 | 3.30 |

Direct effects of each predictor on mortality as evaluated at mediation analysis. No mediated effect was observed as statistically significant. Effect is the increase (decrease) in probability of the outcome between risk factor’s levels. ME is the size (%) of the average causal mediation effects relative to the total effect

Hs-cTnI high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I, CAD coronary artery disease, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, BNP brain natriuretic peptide

Table 3.

Multivariable model for mortality

| OR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDH (270 U/L increase) | 2.70 | 1.20–6.08 | 0.017 |

| Abnormal Hs-cTnI | 32.58 | 3.50–303.31 | 0.030 |

| Chronic coronary artery disease | 5.20 | 1.18–22.94 | 0.008 |

Somer’s Dxy 0.78

Multivariate model showing the independent predictive effect of cardiac injury

LDH lactate dehydrogenase, Hs-cTnI high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I

Fig. 3.

Mediation analysis of an abnormal Hs-cTnI. Average causal mediation effect (ACME) and average direct effect (ADE). Effects are the increase (decrease) in probability of the outcome between risk factor’s levels

Discussion

Cardiac injury is a powerful predictor of mortality in patients with severe COVID-19 infection. However, little is known in non-critically ill COVID-19 patients. Furthermore, it is unclear the relative predictive role of cardiac injury in the context of other comorbidities.

In the present study, we show that: (1) COVID-19 non-survivors show higher Hs-cTnI, both on admission and peak levels. (2) There is a dose–response relationship between Hs-cTnI levels and mortality up to 200 ng/L; (3) Hs-cTnI is the most powerful mediator of in-hospital mortality; (4) This mediation is independent of other underlying confounding variables.

Since the first Chinese observational studies, cardiac injury demonstrated by elevation of cardiac troponins has been reported in 10–30% in-patients with COVID-19 and associated with severe COVID-19 illness, a higher need for intensive care and higher odds of in-hospital mortality [3, 4, 8, 9]. Our data confirmed this observation, yet reporting a higher rate of cardiac injury (38% on admission, 46% during hospitalization) and mortality (18%), which may be explained by the characteristics of our population, represented by older and comorbid patients. Indeed, median age of our patients (71 years) was notably higher than Huang et al. (49 years), Zhou et al. (56 years), Guo et al. (58.5 years), and Shi et al. (64 years) [3, 4, 8, 9]. Along with the age, also comorbidities were more prevalent, with a Charlson comorbidity index ≥ 3 in about one third of patients, and in keeping with previous reports [4, 8, 25, 26], patients with hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and chronic CAD were associated with poor outcome.

Cardiac injury in patients with COVID-19 has been also demonstrated to be predictive of in-hospital mortality [7, 12, 27, 28]. In a metanalysis exploring the risk factors for COVID-19 patients to develop critical disease or death, a Hs-cTnI > 28 pg/mL was associated with an OR of 43.24 (95% CI 9.92–188.49) to deterioration of the patient’s condition [27]. We also found that the risk for mortality increases exponentially with low levels of Hs-cTnI, reaching a plateau at a concentration of about 200 ng/L. These Hs-cTnI levels are uncommonly observed in type-1 acute myocardial infarction or acute myocarditis, and seem likely to be related to myocardial inflammation and supply/demand discrepancy (ischemia).

In the context of elderly and comorbid patients affected by viral pneumonia and systemic inflammation, it can however be problematic to extrapolate the clinical predictive value of cardiac injury, beyond other factors like hypoxemia, hypercoagulation, and systemic inflammation. This is clinically important since experts’ consensus endorse the use of Hs-cTnI after hospitalization as a tool to identify COVID-19 patients with cardiac injury, predict the progression of the disease and set up early treatment approach [29, 30]. Our mediation analysis highlights the central role of cardiac injury in the prediction of mortality, since the peak of Hs-cTnI was the variable with the largest impact on the odds for in-hospital mortality.

The present study has the limitations inherent of single-center, retrospective, observational studies, with a relatively small sample size. Nevertheless, the available sample allows to estimate, assuming a baseline event rate of 20%, a range of OR between approximately 0.3 and 1.8 with a power of 0.80 and the observed effects are all well above the upper limit. We included all patients admitted to our medical COVID-19 Unit for a COVID illness, who did not need any positive-pressure ventilation or were deemed ineligible to it for age or multiple comorbidities; so, our data may not extend to the entire patients with COVID-19, in particular, the most critical patients admitted to ICU. Autopsy cardiovascular studies are needed to advance our knowledge and understanding the pathophysiology of cardiac injury in COVID-19.

In conclusion, the risk stratification is of crucial importance in patients suffering from COVID-19: the use of Hs-cTnI is now considered an important tool to predict outcome. In this study, we not only confirmed that Hs-cTnI is a predictor of in-hospital mortality also in non-critically ill patients with COVID-19, but also that it is the most important mediator independent from any other confounder. Cardiac damage plays a central role in the prognosis of patients with COVID-19 infection.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. S. Continisio, Dr. C. Merola, Dr. A. Arfini and Dr. M. De Zuccato for contribution in data collection. We would like to thank all patients and nurse staff of the Clinica Medica 3, Azienda Ospedaliera—Università di Padova, Italy.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: AC, FC, AA, RV; acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: FC, FD, DC, LM, AS, RP, CS, LP, PF; drafting of the manuscript: AC, FC, AA; critical revision of the manuscript: all authors. Statistical analysis: AC, DG; administrative, technical or material support: SI, RV; study supervision: AA; AC and FC: had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Padova within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Availability of data and material

The data, analytical methods, and study materials will be available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure on reasonable request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human and animal rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Verbal consent from patients for management of personal data was obtained.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Alberto Cipriani and Federico Capone are joint co-first authors.

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China. N Engl J Med. 2019 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2019 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2019 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji Y, Ma Z, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q. Potential association between COVID-19 mortality and health-care resource availability. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(4):e480. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30068-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montagnani A, Pieralli F, Gnerre P, Vertulli C, Manfellotto D, FADOI COVID-19 Observatory Group COVID-19 pandemic and Internal Medicine Units in Italy: a precious effort on the front line. Intern Emerg Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02454-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi S, Qin M, Cai Y, Liu T, Shen B, Yang F, Cao S, Liu X, Xiang Y, Zhao Q, Huang H, Yang B, Huang C. Characteristics and clinical significance of myocardial injury in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(22):2070–2079. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karbalai Saleh S, Oraii A, Soleimani A, et al. The association between cardiac injury and outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Intern Emerg Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02466-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO (2020) Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected: interim guidance, 25 January 2020. Published January 25, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330854. Accessed 30 Mar 2020

- 14.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, Duda SN, REDCap Consortium The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson M, Wells MT, Ullman R, King F, Shmukler C. The Charlson comorbidity index can be used prospectively to identify patients who will incur high future costs. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skulstad H, Cosyns B, Popescu BA, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and cardiac imaging: EACVI recommendations on precautions, indications, prioritization, and protection for patients and healthcare personnel. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeaa072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szerlip M, Anwaruddin S, Aronow HD, et al. Considerations for cardiac catheterization laboratory procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic perspectives from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions Emerging Leader Mentorship (SCAI ELM) Members and Graduates. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;96(3):586–597. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Generalized additive models. London: Chapman and Hall; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods. 2010;15:309–334. doi: 10.1037/a0020761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller AJ. Subset selection in regression. London: Chapman and Hall; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.R Core Team (2019) R: a language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. https://www.R-project.org/

- 23.Tingley D, Yamamoto T, Hirose K, Keele L, Imai K. Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. J Stat Softw. 2014;59:1–38. doi: 10.18637/jss.v059.i05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calcagno V (2019) glmulti: Model Selection and Multimodel Inference Made Easy [Internet]. 2019. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=glmulti

- 25.Du RH, Liang LR, Yang CQ, et al. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00524-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li JW, Han TW, Woodward M, et al. The impact of 2019 novel coronavirus on heart injury: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, et al. Risk factors of critical and mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inciardi RM, Adamo M, Lupi L, Cani DS, Di Pasquale M, Tomasoni D, Italia L, Zaccone G, Tedino C, Fabbricatore D, Curnis A, Faggiano P, Gorga E, Lombardi CM, Milesi G, Vizzardi E, Volpini M, Nodari S, Specchia C, Maroldi R, Bezzi M, Metra M. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 and cardiac disease in Northern Italy. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(19):1821–1829. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guzik TJ, Mohiddin SA, Dimarco A, et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc Res. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atallah B, Mallah SI, AbdelWareth L, AlMahmeed W, Fonarow GC. A marker of systemic inflammation or direct cardiac injury: should cardiac troponin levels be monitored in COVID-19 patients? Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data, analytical methods, and study materials will be available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure on reasonable request.