Abstract

BACKGROUND

Among the various types and causes of mesenteric ischemia, superior mesenteric vein (SMV) thrombosis is a rare and ambiguous disease. If a patient presents with SMV thrombosis, past medical history should be reviewed, and the patient should be screened for underlying disease. SMV thrombosis may also occur due to systemic infection. In this report, we describe a case of SMV thrombosis complicated by influenza B infection.

CASE SUMMARY

A 64-year-old male visited the hospital with general weakness, muscle aches, fever, and abdominal pain. The patient underwent computed tomography (CT) and was diagnosed with SMV thrombosis. Since the patient’s muscle pain and fever could not be explained by the SMV thrombosis, the clinician performed a test for influenza, which produced a positive result for influenza B. The patient had a thrombus in the SMV only, with no invasion of the portal or splenic veins, and was clinically stable. Anticoagulation treatment was prescribed without surgery or other procedures. The follow-up CT scan showed improvement, and the patient was subsequently discharged with continued oral anticoagulant treatment.

CONCLUSION

This case provides evidence that influenza may be a possible risk factor for SMV thrombosis. If unexplained abdominal pain is accompanied by an influenza infection, examination of an abdominal CT scan may be necessary to screen for possible SMV thrombosis.

Keywords: Influenza B virus, Mesenteric ischemia, Venous thrombosis, Mesenteric vascular occlusion, Influenza, Human, Case reports

Core Tip: Superior mesenteric vein (SMV) thrombosis, a potentially fatal type of mesenteric ischemia, usually occurs in individuals with predisposed factors that should be investigated upon diagnosis. Identification of a predisposed factor is crucial in SMV thrombosis because recurrence may be prevented by treatment of the underlying condition. Rarely, an influenza infection can complicate SMV thrombosis, and this report presents the third known case of this occurrence. The evidence presented in this report indicates that SMV thrombosis possibly induced by an influenza virus should be considered when an influenza patient presents with unexplained abdominal pain, or conversely, when an SMV thrombosis patient presents with a high fever of unknown cause. Moreover, the potential treatments for SMV thrombosis including medical interventions, transvenous catheter-based interventions, or surgery may differ according to the degree of vascular involvement and symptoms. These differences are highlighted in this report when the current case is compared to the two previously reported cases.

INTRODUCTION

Mesenteric ischemia is always a serious concern for clinicians. Although epidemiologically mesenteric ischemia is not common, it is a serious disease that may cause patient death. Notably, the symptoms, findings of physical examinations, and complaints from patients with potential mesenteric ischemia are variable, therefore doctors must always be alert to its possible occurrence[1].

Mesenteric ischemia may exhibit different clinical manifestations and display a variable progression, including the type of involved blood vessel, the anatomical location supplied by the damaged blood vessel, the type of vessel damage, whether the vessel is torn or blocked, the timing of the injury, whether the injury is acute or chronic, and the range of the injury[2]. Acute and extensive damage may lead to death due to intestinal necrosis, or the patient may only complain of minor abdominal pain as the collateral vessel has already occurred in a chronic course of the disease.

Among the types of mesenteric ischemia, SMV thrombosis is moderately rare (5%-15%)[3]. The fatality rate of SMV thrombosis is relatively low at 10%-20%; however it is a disease where potentially causal predisposed factors must be investigated[4,5]. SMV thrombosis is typically caused by tumors or inflammation in the abdominal cavity, or by hematological disease and a tendency for over-coagulation. However, in rare cases, SMV thrombosis may occur due to viral infection such as influenza. It is worth noting influenza's extraordinary complications, since influenza A and B infections is occurring in large quantities worldwide regardless of age[6-8]. Herein we report a case of SMV thrombosis complicated by influenza B infection.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 64-year-old man visited the local medical center on March 4th with a complaint of general weakness, myalgia, and abdominal pain, which had begun a week prior to the visit.

History of present illness

The patient underwent computed tomography (CT) at the local medical center where he was diagnosed with thrombosis of the SMV, and was subsequently transferred to our hospital. The abdominal CT scan revealed a large thrombus running straight from the SMV gastrocolic trunk to the distal site, totally obstructing a segmental portion of the SMV. Additionally, the surrounding fat stranding and bowel wall edema of the ascending colon were confirmed.

The patient had a fever of 37.9 °C at the time of the visit, and complained that he felt hot. He also complained of a headache, but there was no cough, sputum, diarrhea, or vomiting.

History of past illness

Over the previous 5-years, the patient had been prescribed 1000 mg metformin once daily (Q.D.), 1 mg glimepiride Q.D., 2.5 mg linagliptin Q.D., 50 mg losartan Q.D., and 10 mg rosuvastatin Q.D. for hypertension and diabetes.

Physical examination

The patient continued to complain of a dull pressing pain in the right upper quadrant, with mild tenderness in the area during the physical examination. The bowel sound was hypo-active, and there were no other specific findings in other physical examinations.

Laboratory examinations

Blood tests revealed that the white blood cell count was 16160 /mL, the level of ESR was 86 mm/hr, and the level of HS-CRP was 16 mg/dL. Although SMV thrombosis was diagnosed, the patient only complained of mild tenderness, and no rebound tenderness. However, there were complaints of fever and muscle pain throughout the body. Since the patient’s symptoms were considered atypical for SMV thrombosis, a sample was collected through a nasopharyngeal swab and an Influenza A/B rapid antigen test was performed. The influenza test was performed using "The BD Veritor™ Plus System for Rapid Detection of Flu A+B" kit, sensitivity 81.3% (71.1%, 88.5%, 95% confidence interval), specificity 98.2% (95.7%, 99.3%, 95% confidence interval). In addition, after collecting samples through nasopharyngeal swab, coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) test by RT-PCR was performed by taking account of recent pandemic situation.

Imaging examinations

The abdominal CT scan revealed a large thrombus running straight from the SMV gastrocolic trunk to the distal site, totally obstructing a segmental portion of the SMV. Additionally, the surrounding fat stranding and bowel wall edema of the ascending colon were confirmed.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The test showed a positive result for influenza B. The test for COVID-19 was negative.

TREATMENT

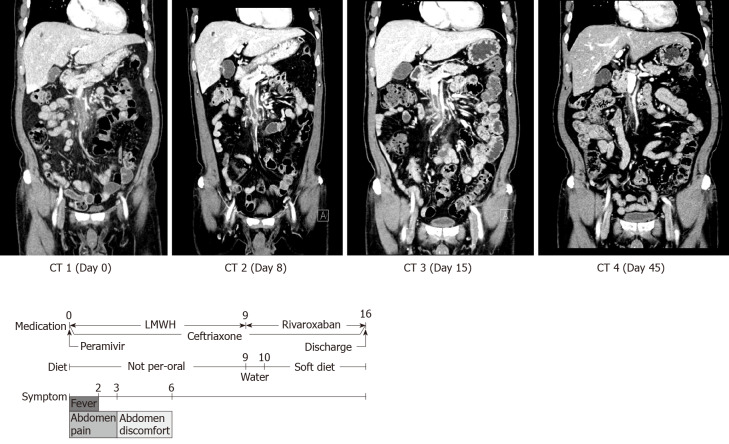

A single dose of 300 mg of peramivir was administered intravenously (Figure 1). An emergency laparotomy was not performed. However, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for close observation, and a dose of 60 mg of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) was subcutaneously injected twice per day (B.I.D.). The patient was not allowed any oral intake, and total parenteral nutrition was administered. In addition, a dose of 2 g ceftriaxone was administered Q.D. as a prophylactic antibiotic. The patient exhibited fever until March 6th (day 2 of the hospital visit), which subsequently abated. He complained of abdominal pain until March 7th (day 3), and continued to complain of abdominal discomfort until March 10th (day 6). A follow-up CT scan was performed on March 12th (day 8), and revealed that the overall size of the thrombus had decreased. The patient drank some water, and the medication was changed from LMWH to 15 mg rivaroxaban B.I.D. on March 13th. Subsequently, the patient ate a soft diet and was moved from the ICU to the general hospital ward on March 14th (day 10).

Figure 1.

Case in-hospital course with computed tomography scan, medication, and symptoms. CT: Computed tomography; LMWH: Low molecular weight heparin.

The 3rd follow-up CT scan was performed on March 19th, and revealed that the thrombus was markedly reduced. The patient was discharged on March 20th (day 16). During the hospital stay, the patient was tested for several factors which could potentially cause hypercoagulation, including tumor markers, lupus anticoagulant, rheumatoid factor, protein S activity, and protein C activity. All the results were negative. A consultation with a rheumatology and hematology specialist did not uncover any other suspected underlying diseases.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

After discharge, regular outpatient follow-up visits are underway, and all symptoms have improved. The patient underwent CT again one month after discharge (day 45), and SMV thrombosis was not seen.

DISCUSSION

SMV thrombosis is a rare disease. A study in Sweden found that only 2.7 of the 100000 patients developed SMV thrombosis between 2000–2006[9]. Approximately, 5%-15% of all acute mesenteric thromboses are SMV thrombosis, with a low rate of vascular bowel disease[4]. If mesenteric venous thrombosis does occur, it is necessary to determine whether it is caused by certain risk factors. Risk factors include venous compression due to abdominal mass (tumor, cyst), inflammation of the abdomen (pancreatitis, diverticulitis, and inflammatory bowel disease)[10], portal hypertension, and liver cirrhosis. It is also important to determine whether the mesenteric venous thrombosis resulted from acquired thrombophilia (malignancy), or inherited thrombophilia (Factor V Leiden mutation, the prothrombin G20210A mutation, protein S deficiency, protein C deficiency, antithrombin III deficiency, activated protein C resistance, or antiphospholipid syndrome), and any personal or family history of thromboembolism must be confirmed[3,11]. SMV thrombosis is rarely caused by viral infection[12,13]. However, the SMV thrombosis case in this report occurred simultaneously with influenza B.

Previous studies have shown that influenza infection may cause thrombosis[14]. Thromboses caused by viral infection may be explained as a results of systemic infection, rather than a local infection in the abdominal cavity. Systemic infections activate IL-6, IL-1b, and TNF-a. These proteins are proinflammatory cytokines that activate platelets and activated platelets adhere to endothelial cells. Infections also increase transcription of tissue factor (TF), which combines with factor VIIa to form the TF-VIIa complex. The TF-VIIa complex activates factor X as factor Xa, and forms a prothrombinase complex with other coagulation factors. This cascade eventually forms thrombin, and transforms fibrinogen into fibrin. The inflammation due to infection creates thrombosis through activation of platelets, which bind to damaged cells, and activate coagulation factors[15-17]. Also, thrombosis is observed in 6.4 % of patients with acute cytomegalovirus infection[18] and 2.6/10000 patient-years with chronic human immunodeficiency virus infection[19]. Deep vein thrombosis is highly occurred after community-acquired upper respiratory infection and urinary tract infection[20], and hypercoagulation and disseminated intravascular coagulation are caused by several bacterial infections like sepsis[21].

According to previous reports, there have been two cases of SMV thrombosis associated with influenza; the first case was an influenza A patient with protein S deficiency, and the second case was an influenza B patient without any other identified underlying diseases (Table 1)[12,13].

Table 1.

Comparison of three cases of superior mesenteric vein thrombosis complicated by influenza

| No. | Age (yr) | Sex | Symptom | Comorbidity | Blocked vessel | Surgery and other procedures | Oral medication |

| 1 | 5 | Female | Abdominal pain, vomiting and bloody stool after 2 wk of influenza A | Influenza A and protein S deficiency | Complete SMV thrombosis and partial PV and SV thrombosis | Surgical resection of small bowel | Warfarin |

| 2 | 44 | Male | Abdominal pain (twisting and pulling inside) after 3 d of influenza B | Influenza B | Complete SMV thrombosis and partial PV and SV thrombosis | Transhepatic thrombolysis | Rivaroxaban |

| This case | 64 | Male | Fever and abdominal pain for 7 d | Influenza B | Complete SMV thrombosis not involving PV and SV | None | Rivaroxaban |

SMV: Superior mesensteric vein; PV: Portal vein; SV: Splenic vein.

In the first case, a 5-year-old girl presented with abdominal pain and bloody stool 2 wk after a diagnosis of influenza A. After examination, complete thrombosis of the SMV, and partial thromboses of the portal vein (PV) and splenic vein were identified. In addition, bowel ischemia of the small intestine was confirmed, and surgical excision was performed. Subsequently, the patient was prescribed preventative warfarin. Sequence analysis detected a heterozygous K196E mutation in the PROS1 gene, and type 2 protein S deficiency was diagnosed.

In the second case, a 44-year-old man with no medical history was diagnosed with influenza B after experiencing a fever for one day. The patient returned 3 d after the influenza diagnosis with a complaint of abdominal pain. During the examination, a thrombus extending to the main PV and splenic vein as well as the SMV was identified, and the patient received transhepatic thrombolysis. The patient subsequently recovered and was discharged with a prescription for rivaroxaban.

The case described in this report is the third case documenting SMV thrombosis combined with influenza infection. Since the PV was not invaded, this case followed a more stable course compared to the previous cases, without any requirement for surgery or other procedures.

Current treatment of SMV thrombosis includes anticoagulation therapy, laparoscopic exploration with thrombectomy, transvenous thrombolysis, or transvenous thrombectomy[12,22]. There are no clear guidelines on the proper choice of treatments, however emergency surgery should not be delayed if the patient exhibits intestinal necrosis. Fortunately, in our case, the patient only required anticoagulants and other conservative treatments, unlike the patients in the previously published case reports. Since catheter-based techniques have been widely recognized for vascular disease, it is thought that further studies on the effect of transvenous catheter-based techniques on SMV thrombosis are needed.

The current case describes a patient presenting with abdominal pain who underwent CT, enabling a diagnosis of SMV thrombosis. However, since the clinical features and symptoms were not typical for SMV thrombosis, influenza was suspected, and a subsequent test result was positive for influenza B. Collectively, this information allowed the patient to receive adequate treatment resulting in a favorable clinical outcome.

CONCLUSION

Herein we report a rare case of influenza B complicating SMV thrombosis, and compare it with two separate previously published cases documenting either influenza A or B combined with SMV thrombosis. Based on the current case, we determined that if an influenza patient presents with a complaint of unexplained abdominal pain, SMV thrombosis should be considered, and a proper examination, such as a CT scan, should be performed to enable a correct diagnosis.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: None.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: May 4, 2020

First decision: May 21, 2020

Article in press: August 25, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Baymakova M, Wijaya R S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu YXJ

Contributor Information

Gyu Man Oh, Department of Internal Medicine, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan 49267, South Korea.

Kyoungwon Jung, Department of Internal Medicine, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan 49267, South Korea. forjkw@gmail.com.

Jae Hyun Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan 49267, South Korea.

Sung Eun Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan 49267, South Korea.

Won Moon, Department of Internal Medicine, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan 49267, South Korea.

Moo In Park, Department of Internal Medicine, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan 49267, South Korea.

Seun Ja Park, Department of Internal Medicine, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan 49267, South Korea.

References

- 1.Brandt LJ, Boley SJ. AGA technical review on intestinal ischemia. American Gastrointestinal Association. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:954–968. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70183-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clair DG, Beach JM. Mesenteric Ischemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:959–968. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1503884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar S, Sarr MG, Kamath PS. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1683–1688. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra010076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunaud L, Antunes L, Collinet-Adler S, Marchal F, Ayav A, Bresler L, Boissel P. Acute mesenteric venous thrombosis: case for nonoperative management. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:673–679. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.117331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abu-Daff S, Abu-Daff N, Al-Shahed M. Mesenteric venous thrombosis and factors associated with mortality: a statistical analysis with five-year follow-up. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1245–1250. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0833-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popov G, Baymakova M, Andonova R. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of hospitalized patients with Influenza type B in the 2017-2018 season. General Medicine. 2018;20(4):3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korsun N, Angelova S, Trifonova I, Georgieva I, Voleva S, Tzotcheva I, Mileva S, Ivanov I, Tcherveniakova T, Perenovska P. Viral pathogens associated with acute lower respiratory tract infections in children younger than 5 years of age in Bulgaria. Braz J Microbiol. 2019;50:117–125. doi: 10.1007/s42770-018-0033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korsun NS, Angelova SG, Trifonova IT, Georgieva IL, Tzotcheva IS, Mileva SD, Voleva SE, Kurchatova AM, Perenovska PI. Predominance of influenza B/Yamagata lineage viruses in Bulgaria during the 2017/2018 season. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147:e76. doi: 10.1017/S0950268818003588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acosta S, Alhadad A, Svensson P, Ekberg O. Epidemiology, risk and prognostic factors in mesenteric venous thrombosis. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1245–1251. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida H, Granger DN. Inflammatory bowel disease: a paradigm for the link between coagulation and inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1245–1255. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singal AK, Kamath PS, Tefferi A. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayakawa T, Morimoto A, Nozaki Y, Kashii Y, Aihara T, Maeda K, Momoi MY. Mesenteric venous thrombosis in a child with type 2 protein S deficiency. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33:141–143. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181fce4d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins MH, McGinn MK, Weber DJ. Mesenteric Thrombosis Complicating Influenza B Infection. Am J Med. 2016;129:e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt M, Horvath-Puho E, Thomsen RW, Smeeth L, Sørensen HT. Acute infections and venous thromboembolism. J Intern Med. 2012;271:608–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstrong SM, Darwish I, Lee WL. Endothelial activation and dysfunction in the pathogenesis of influenza A virus infection. Virulence. 2013;4:537–542. doi: 10.4161/viru.25779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Short KR, Veldhuis Kroeze EJ, Reperant LA, Richard M, Kuiken T. Influenza virus and endothelial cells: a species specific relationship. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:653. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levi M, van der Poll T, Schultz M. Infection and inflammation as risk factors for thrombosis and atherosclerosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2012;38:506–514. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1305782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Justo D, Finn T, Atzmony L, Guy N, Steinvil A. Thrombosis associated with acute cytomegalovirus infection: a meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22:195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan PS, Dworkin MS, Jones JL, Hooper WC. Epidemiology of thrombosis in HIV-infected individuals. The Adult/Adolescent Spectrum of HIV Disease Project. AIDS. 2000;14:321–324. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200002180-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smeeth L, Cook C, Thomas S, Hall AJ, Hubbard R, Vallance P. Risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after acute infection in a community setting. Lancet. 2006;367:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis RP, Miller-Dorey S, Jenne CN. Platelets and coagulation in infection. Clin Transl Immunology. 2016;5:e89. doi: 10.1038/cti.2016.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvi AR, Khan S, Niazi SK, Ghulam M, Bibi S. Acute mesenteric venous thrombosis: improved outcome with early diagnosis and prompt anticoagulation therapy. Int J Surg. 2009;7:210–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]