Abstract

BACKGROUND

Sweet’s syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is a rare skin disorder that may be associated with cancer.

CASE SUMMARY

A 58-year-old female presented with a cholestatic syndrome and significant weight loss three months before admission. Five months earlier, she had abruptly developed skin lesions with erythematous papules that evolved to erythematous blisters. Clinical evaluation and laboratory tests confirmed hepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Skin lesions histopathological findings showed neutrophilic dermatosis, massive edema, fibrin, necrosis, and elastosis. These results, in association with the macroscopic aspects of the findings, led to the diagnosis of paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome due to cholangiocarcinoma. As staging was consistent with an advanced tumor without a cure perspective, we opted to perform percutaneous biliary drainage, and subsequently, palliative care. Eventually, after a few weeks, the patient died.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the diagnosis of the underlying disease-causing Sweet’s syndrome must be accurate, and patients need to be followed-up, as neoplasia such as cholangiocarcinoma may be a later manifestation.

Keywords: Cholangiocarcinoma, Paraneoplastic syndrome, Sweet syndrome, Case report, Bullous lesions, Cholestasis

Core Tip: Sweet's syndrome preceding solid neoplasia, especially cholangiocarcinoma, is a rare condition. Only two cases of Sweet's syndrome associated with cholangiocarcinoma have been reported. Bullous skin lesions should be evaluated with a broad differential diagnosis, including the possibility of preceding the diagnosis of neoplasia. The evaluation and follow-up of patients with this condition is essential, seeking diagnosis and treatment in early stages of the neoplastic lesion.

INTRODUCTION

Sweet’s syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is a rare inflammatory disorder characterized by the abrupt appearance of painful, edematous, and erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules on the skin. Fever and leukocytosis frequently accompany the cutaneous lesions. It may be clinically divided into three types: Classical or idiopathic, malignancy-associated, and drug-induced[1]. The malignancy-associated form was described in approximately 20% of Sweet’s syndrome cases[2]. Within these cases, the most common reported association has been with hematopoietic neoplasia (nearly in 85%), while fewer cases were associated with solid tumors, as was our described case[3]. It is interesting to note that there is a scarcity of case reports about the association between Sweet’s syndrome and cholangiocarcinoma. Therefore, we describe the case of a patient who was diagnosed with the paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome and had this malignant biliary tumor, to remind physicians about this possible association.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 58-year-old female presented at our service on March 21st of 2018, with a three-month history of cholestasis symptoms, as well as significant weight loss (about 20 kg). She reported jaundice, choluria, acholia, and itching.

History of present illness

Two months before the development of the gastrointestinal symptoms, she had suddenly progressed with skin lesions (erythematous papules) that evolved to erythematous blisters.

History of past illness

She denied other comorbidities, fever, and diarrhea.

Physical examination

On physical examination, she was malnourished, pale, afebrile, and presented significant jaundice. The abdominal exam was remarkable for a mild diffuse abdominal tenderness to deep palpation, as well as for an enlarged nontender, firm, and irregular liver. There were also blistering and crusted skin lesions, simulating pemphigus, throughout the scalp, hands, and feet (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Blistering skin lesions suggesting pemphigus on foot (A) and hands (B).

Laboratory examinations

Tumor markers analysis showed a CA 19.9 of 1281.5 U/mL (upper limit of normal, 37.0 U/mL), alpha-fetoprotein of 2.13 ng/mL (upper limit of normal, 10.0 ng/mL), and CEA of 14.8 ng/mL (upper limit of normal, 4.9 ng/mL). The remaining laboratory tests showed leukocytes count of 8.900/m3 (80%, neutrophils), C-reactive protein of 23 mg/L (upper limit of normal, 10.0 mg/L), marked increased cholestatic liver enzymes, and bilirubin levels. Aminotransferases were mild to moderately elevated.

Imaging examinations

The patient underwent an abdomen computed tomography that revealed an infiltrative mass causing dilatation of the bile ducts, as well as increased mesenteric lymph nodes, and ascites (Figures 2 and 3). Further investigation with a magnetic resonance of the upper abdomen with cholangiopancreatography, confirmed stricture of the common bile and hepatic ducts due to probable neoplasia, and upstream dilatation of the biliary tree.

Figure 2.

Axial plane image of computed tomography obtained in the portal phase showing significant intrahepatic biliary tract dilatation (orange arrows).

Figure 3.

Axial plane image of computed tomography obtained in the portal phase showing an infiltrative aspect of the tumor, with irregular contour and mild contrast enhancement located at the common bile duct (orange arrows) determining biliary tract dilatation.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The patient underwent an echo-endoscopy with fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the tumor that confirmed the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma. Biopsies of the skin blistering and crusted lesions simulating pemphigus throughout the scalp, hands, and feet, were performed. Microscopy analysis showed neutrophilic dermatosis with massive edema, fibrin, necrosis, and elastosis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Skin lesions biopsy stained with hematoxylin-eosin showed elastosis (yellow arrow), edema (orange arrow), bleeding focus and red cells extravasation (black arrows) (A) and capillary destruction (B).

TREATMENT

The aforementioned results, in association with the macroscopic aspects of the lesions, led to the diagnosis of paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome. The patient was started on steroids and antihistaminies to treat the skin lesions without success.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

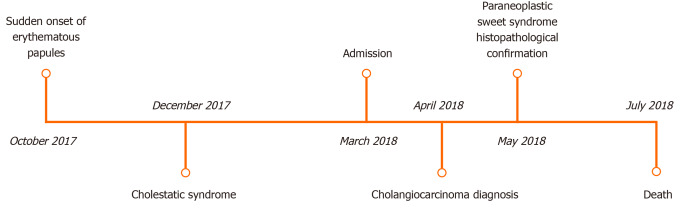

Due to the advanced stage of the tumor, with no cure perspective, we opted to perform percutaneous biliary drainage for symptomatic relief and subsequent palliative care. Figure 5 describes the chronology of the events.

Figure 5.

Timeline of events reported in the clinical case.

DISCUSSION

We reported the case of a patient diagnosed with Sweet’s syndrome as a paraneoplastic manifestation of a cholangiocarcinoma, in which the primary symptoms were cholestatic syndrome and weight loss. The clinical evolution, laboratory tests, and skin lesions biopsy results made it possible to confirm the diagnosis of Sweet’s syndrome based on Su and Liu’s criteria[4] (1896) modified by von den Driesch[5]. Sweet’s syndrome is characterized by the sudden appearance of erythematous papules and/or plaques, which can contain vesicular surfaces and usually affect thorax, back, face, neck, and upper extremities[5]. Our patient presented with abrupt onset of erythematous papules, histopathological evidence of dense neutrophilic infiltrate with no signs of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and had an underlying visceral malignancy. Laboratory values at presentation showed > 8000 leukocytes as well > 70% neutrophils.

There are three possible clinical categorizations for this syndrome based upon etiology: Classical or idiopathic, malignancy-associated, and drug-induced[1]. Malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome corresponds to approximately 20% of the cases[2]. It is most associated with hematological neoplasia (in 85% of the cases), and less frequently, with solid tumors, as was the case of our patient[3]. The main form of presentation in these cases associated with malignancy is as a paraneoplastic syndrome. The appearance of the skin lesions can precede the primary illness’ diagnosis in months to years[6]. The histopathological and laboratory test results favored the patient’s diagnosis of a paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome in our case.

Gold standard treatment is to administer systemic steroid therapy, which may lead to a fast remission of the symptomatology. Treatment of the primary underlying disease is also related to the chances of patient recovery[3]. Nevertheless, in our case, corticosteroid and antihistamine therapy were unsuccessful. Another therapeutic approach that we adopted was biliary drainage to proportionate symptomatic relief. There are no current well-established guidelines to treat malignancy-associated Sweet's syndrome[3].

To our knowledge, there are only two reported cases of Sweet’s syndrome in association with cholangiocarcinoma. The first case ever describing this association, was published in 2006. In this case of a 68-year-old woman, skin lesions preceded the diagnosis of the malignant tumor, as it occurred with our patient[7]. The other case report described a 72-year-old man with cholangiocarcinoma in which Sweet’s syndrome manifested 3 years after the initial diagnosis, five months after chemotherapy interruption due to a semi-urgent surgery[8].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the diagnosis of the underlying disease-causing Sweet’s syndrome must be accurate, and patients need to be followed-up, as neoplasia such as cholangiocarcinoma may be a later manifestation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Digestive Endoscopy, Radiology, and the Surgery teams at the Hospital Geral Roberto Santos for their support in the clinical management of the case. We also thank Fiocruz-Bahia for kindly providing the images shown on this case report.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: The written informed consent was provided.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors worked on this case and none of them have conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors read the CARE checklist (2016) and the case report was prepared and revised in accordance with the CARE checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: April 19, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Article in press: August 29, 2020

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fava G, Zhang X S-Editor: Huang P L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

Contributor Information

Camille Carneiro Lemaire, Department of Internal Medicine, Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública, Salvador 40290-000, Bahia, Brazil.

Ana Luisa Carvalho Portilho, Department of Internal Medicine, Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública, Salvador 40290-000, Bahia, Brazil.

Luciana V Pinheiro, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Salvador 41180-780, Bahia, Brazil.

Rafael Alves Vivas, Department of Surgery, Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Salvador 41180-780, Bahia, Brazil.

Maíra Britto, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Salvador 41180-780, Bahia, Brazil.

Melaine Montenegro, Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Salvador 41180-780, Bahia, Brazil.

Luiz Felipe de Farias Rodrigues, Department of Radiology, Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Salvador 41180-780, Bahia, Brazil.

Sérgio Arruda, Pathological Anatomy, Fiocruz - Bahia, Universidade Estadual da Bahia, Salvador 40000-000, Bahia, Brazil.

André Castro Lyra, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Federal University of Bahia and Gastro-Hepatology Service, Salvador 40295-050, Bahia, Brazil.

Lourianne Nascimento Cavalcante, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Federal University of Bahia and SED-CHD Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Salvador 40295-050, Bahia, Brazil. lourianne@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Cohen PR. Sweet's syndrome--a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet's syndrome and cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:149–157. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(93)90112-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raza S, Kirkland RS, Patel AA, Shortridge JR, Freter C. Insight into Sweet's syndrome and associated-malignancy: a review of the current literature. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:1516–1522. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet's syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von den Driesch P. Sweet's syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535–556; quiz 557-560. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung VQ, Moschella SL, Zembowicz A, Liu V. Clinical and pathologic findings of paraneoplastic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:745–762; quiz 763-766. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinojima Y, Toma Y, Terui T. Sweet syndrome associated with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma producing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. B. r J Dermatol. 2006;155:1103–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Opneja A, Mahajan S, Kapoor S, Marur S, Yang SH, Manno R. Unusual Paraneoplastic Presentation of Cholangiocarcinoma. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:806835. doi: 10.1155/2015/806835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]