Abstract

With an estimated incidence of only 1-2 cases in every 1 million people, hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (HEHE) is a rare vascular endothelial cell tumor occurring in the liver and consisting of epithelioid and histiocyte-like vascular endothelial cells in mucus or a fibrotic matrix. HEHE is characterized as a low-to-moderate grade malignant tumor and is classified into three types: solitary, multiple, and diffuse. Both the etiology and characteristic clinical manifestations of HEHE are unclear. However, HEHE has a characteristic appearance on imaging including ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography/computerized tomography. Still, its diagnosis depends mainly on pathological findings, with immunohistochemical detection of endothelial markers cluster of differentiation 31 (CD31), CD34, CD10, vimentin, and factor VIII antigen as the basis of diagnosis. Hepatectomy and/or liver transplantation are the first choice for treatment, but various chemotherapeutic drugs are reportedly effective, providing a promising treatment option. In this review, we summarize the literature related to the diagnosis and treatment of HEHE, which provides future perspectives for the clinical management of HEHE.

Keywords: Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, Diagnosis, Differential diagnosis, Therapy, Prognosis, Imaging

Core Tip: In this work, we review the updated diagnosis and therapy of the hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, which is an extremely rare tumor of vascular origin with an incidence of < 0.1 per 100000 population. It is hard to differentiate from other liver lesions and there is no standard strategy for treating it based on its rarity. Our work helps to better understand and treat this rare disease.

INTRODUCTION

Epithelioid angioendothelioma (EHE) is a rare vascular endothelial cell tumor composed of epithelioid and histiocyte-like vascular endothelial cells in mucus or fibrotic matrix. The World Health Organization now classifies EHE as having complete malignant potential[1]. It can occur in multiple parts of the body such as the lungs, soft tissue, head and neck, pleura, bones and many other organs. EHE in the liver, or hepatic EHE (HEHE) is an even rarer disease, with a reported incidence of 1-2 of every 1 million people[2]. HEHE most commonly occurs between the ages of 30 and 50 years, with a predominance in females based on a male:female incidence ratio of 2:3[3]. It can be characterized as single, multiple, or diffuse, and the multifocal form is most common. It is considered a low-to-medium grade malignant tumor[4], and the degree of malignancy is between that of hemangioma and that of hemangiosarcoma of the liver[5]. HEHE contains dendritic-like cells and epithelioid tumor cells, which infiltrate the sinuses of the liver[6]. A diffuse appearance is observed in the late stage of focal complication, which is related to the infiltration of hepatic vascular and the portal vein, and is often associated with distant metastasis. The lung, peritoneum, spleen, lymph nodes, and bone are the most common sites of extrahepatic involvement[7]. The characteristic clinical manifestations remain unclear[8]. Prior research has indicated that about 80% of patients are initially misdiagnosed due to variable and atypical clinical manifestations[3], and the diagnosis of HEHE is typically only made upon pathological examination. In addition, the imaging features of HEHE are nonspecific, and differentiation from multifocal metastasis (such as those originating from breast or colon cancer), multifocal liver cancer, peripheral cholangiocarcinoma, abscess and cavernous hemangioma, and other conditions must be achieved. The main imaging features of HEHE on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) are the peripheral location of the nodules, the contraction of the capsule, and the tendency of multiple foci to merge[9,10], although one study concluded that capsule retraction is observed only for nodules with a diameter greater than 2.0 cm[9].

The etiology of HEHE also remains unclear. Several possible pathogenic factors and risk factors have been identified such as exposure to chloroethylene, polyurethane, or silica; oral contraceptive use; primary biliary cirrhosis; viral hepatitis; exposure to asbestos; and alcohol use[7]. Moreover, a special translocation t (1/3) (P36/25) is reportedly specific to HEHE, but how the fusion transcripts lead to tumorigenesis has not been elucidated[11].

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF HEHE CASES

Most patients with HEHE have no history of hepatitis infection, and no typical clinical manifestations of the disease have been observed. According to one study, the most common symptoms included right upper abdominal pain (48.6%), hepatomegaly (20.4%) and weight loss (15.6%), with a few cases also experiencing brucellosis or Kasabakh-Merritt syndrome[12]. Liver function as well as levels of serum alpha fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carcinoantigen 199 are generally within the normal ranges in HEHE patients, and thus, these indicators have no significant value in the diagnosis of HEHE[3,13]. In another study, 36.6% of HEHE patients had extrahepatic involvement, with organs such as the lung (8.5%), local lymph nodes (7.7%), peritoneum (6.1%), bone (4.9%), spleen (3.2%) and diaphragm (1.6%) as the most commonly involved sites[3]. It was reported that 25% of patients had no obvious symptoms[3]. Initial symptoms have included pain in the right upper abdomen, ascites, weight loss, anorexia and jaundice in the late stage[3] as well as portal hypertension[2]. Some cases even presented with liver failure caused by a very large tumor[14], spontaneous rupture of the tumor[15] or corresponding symptoms caused by metastatic lesions, such as pleural effusion[16]. The tumor may appear as a single or multifocal tumor, and cases with a single lesion accounted for only 13%-18% of HEHE cases in the study by Mehrabi et al[3]. If the tumor is large and convex, it can be palpated as an abdominal mass. In one reported case of HEHE, the tumor measured 20.1 cm × 14.7 cm × 20.7 cm and ruptured[14].

AUXILIARY EXAMINATION

Imaging

HEHE lesions typically appear as hypoechoic on ultrasound. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) can provide enhanced detection ability for multi-focal HEHE, which shows a typical enhancement pattern of high enhancement in the arterial phase and low enhancement in the portal phase and delayed phase[17]. The malignant nature of HEHE can be judged by CEUS by analyzing the low enhancement in portal phase and delayed phase. CEUS has been used to view multiple subcystic hypoechoic focal liver lesions with regular shape[18]. The typical HEHE sign is concentric enhancement of contrast medium in the vascularized components and almost no enhancement in the corresponding center consisting of fibrotic tissue. Some tumors may also show fine calcification[19].

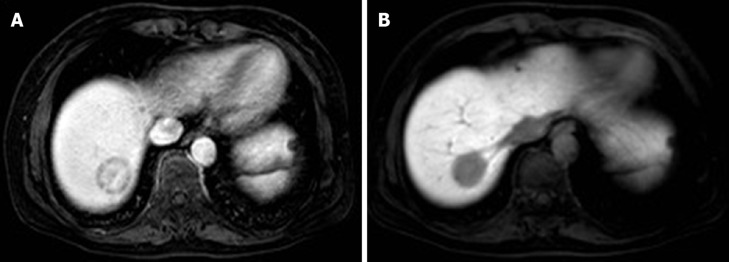

On MRI, T1-weighted imaging will show a low signal at the tumor and T2-weighted imaging will show a high signal[20]. Paolantonio et al[21] reported some specific diagnostic performance of MRI for HEHE, particularly for T2-weighted imaging and dynamic studies. Specific imaging features of HEHE included a target sign on T2 imaging, represented by a white target-like sign, consisting of a high signal intensity core, a low signal intensity thin ring, and a weak high signal intensity halo, corresponding to the dense fibrous myxoid stroma with necrotic areas, proliferating tumor cells and the peripheral avascular zone resulting from vascular infiltration or occlusion of hepatic sinusoids and small vessels[10]. The white target-like sign appears as low signal intensity on contrasted enhanced T1-weighted imaging, whereas on contrast-enhanced imaging, the target sign appears as a black target-like sign (Figure 1A), showing gradual peripheral ring-like enhancement patterns with central low signal intensity in the arterial to delay phases, with the enhanced lesion frequently surrounded by a thin, hypointense ring on the portal or delay phases[20]. A lollipop sign (Figure 1B) is formed by extension or termination of the hepatic vein or portal vein and its branches to the edge of the nodule[13]. The lollipop sign is formed by the enhanced imaging of the clear tumor mass (the candy in the lollipop) and the adjacent blocking vein (bar), because of the tendency of HEHE to spread within the branches of the portal vein and the hepatic vein[22]. Although the vein should terminate smoothly at the edge of the lesion or inside of the lesion, a vessel across the entire lesion or a displaced vessel may not be included in the sign[10]. CT or MRI typically show gradual, ring-like enhancement enhanced, but it was reported that in cases with multiple lesions less than 2.0 cm in diameter, mild, homogeneous enhancement of the arterial phase is observed[13].

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging. A: Magnetic resonance imaging shows a target-like sign as a gradual peripheral ring-like enhancement pattern with central low signal intensity in the arterial to delay phases, and the enhanced lesion is surrounded by a thin, hypointense ring on contrasted-enhanced T1-weighted image; B: The lollipop sign consists of a clear tumor mass (candy in the lollipop) and adjacent occluded vein (rod).

The importance of 18F-labeled fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT 18F-FDG PET/CT in the detection and recurrence of EHE has been widely reported[23]. 18F-FDG PET/CT offers a significant advantage for detecting potential metastasis, especially diffuse metastasis, in patients with HEHE. Most HEHE tumors show a slight increase in the uptake of FDG, which was different from cholangiocarcinoma, which presents with high uptake[24]. Kitapci et al[25] suggested that double-time 18F-FDG PET/CT may be of great significance for the detection of EHE and the judgement of the degree of the disease[25], because some of the lesions not found in early scanning could be detected by delayed scanning. Dong et al[23]reported that 18F-FDG PET/CT findings correlated with the histopathological features of the tumor and hypothesized that the extent of glucose uptake in the EHE tissue might be related to the size of the cells rather than the size of the tumor[23]. Therefore, in tumors with a high cell density, the uptake of FDG is increased due to the increase in glucose metabolism, whereas in tumors with a low cell density and relatively more stroma, the uptake of FDG will be lower. Suga et al[26] reported the application of 18F-FDG PET/CT for monitoring the response of HEHE to radiation[26]. After 7 mo of radiotherapy, FDG uptake disappeared in hepatic nodules, while FDG uptake in other untreated nodules continued to be strong. Another study reported a role for 18F-FDG PET/CT in the evaluation of tumors after use of the anti-angiogenic drug Pazopanib[27]. Finally, one imaging study of 47 nodules in 12 patients revealed that MRI using gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-EOB-DTPA) as the contrast agent is a viable approach to analyzing the core pattern of the hepatic choledochal phase (HBP) as a feature of HEHE[28].

Gross pathology

On pathological examination, HEHE tumor nodules are white, brown, yellow or yellowish brown, with unclear boundaries[4,29,30]. The reported tumor nodules have varied in size, with the largest measuring 20.7 cm[14]. On palpation, nodules may feel hard or rubbery, if calcification is present, and the surface may have a gravely texture[31].

Histology and cytology

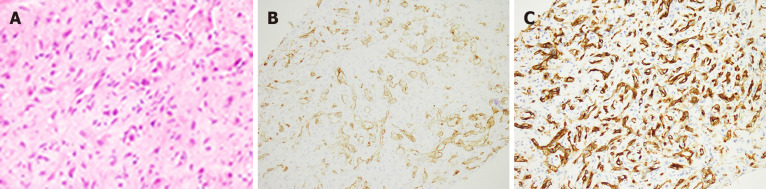

Histologically, HEHE appears as nests and cords of epithelioid endothelial cells spread throughout a myxohyaline stroma. Another classic histological feature of these tumors is the presence of intracytoplasmic lumina[32]. HEHE is characterized by three types of cells: Epithelial-like cells (rich in eosinophilic cytoplasm and atypical nuclei), dendritic cells (astroplasmic processes) and intermediate cells (characteristics between epithelial-like cells and dendritic cells) (Figure 2A). These cells are typically embedded in mucus hyaluronate or hardened matrix. In addition, epithelioid cells and dendritic cells may contain cytoplasmic vacuoles, showing a signet ring-like or vesicular appearance[33,34]. The tumor cells express the endothelial markers CD31 (Figure 2B), CD34 (Figure 2C), CD12, vimentin and factor VIII antigen[32,35]. Consistently, additional studies found that factor VIII staining was positive in 99% of case, CD34 staining was positive in 94%, and CD31 staining was positive in 86%, whereas very little staining of quercetin and abundant staining of collagen IV and laminin were observed[30,36]. Finally, cell heteromorphism, nuclear fission, the presence of fusiform cells, changes in necrotic tumors and a Ki-67 index > 10%-15% were shown to be the features of more aggressive HEHE[37,38].

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining. A: Hematoxylin and eosin staining showing epithelioid and dendritic cells forming primitive vascular structures with a myxoid matrix in epithelioid angioendothelioma (EHE); B: Positive membranous staining for cluster of differentiation (CD31) in epithelioid angioendothelioma, highlighting primitive vascular structures; C: Positive membrane staining for CD34 in EHE, highlighting primitive vascular structures.

MOLECULAR CHARACTERIZATION OF HEHE

Nuclear CAMTA1 expression was observed in 85% of HEHE tumors[39,40]. Because of the interaction of the t (1,3) (p36; q25) translocation, recurrent WWTR1–CAMTA1 gene fusions were observed in about 90% of EHE cases[41,42]. Errani et al[42] found CAMTA1 and WWTR1 translocation in 17 EHE patients by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)[42]. CAMTA1 is a calmodulin-binding transcriptional activator, and WWTR1 is a transcription coactivator[43]. A variant of EHE presents with a rearrangement deletion of WWTR1–CAMTA1 and an alternative gene fusion YAP1–TFE3, and is characterized by well-formed vasoformative tumors, with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, atypical cytogenetics, pseudo-alveoli and partly solid-state growth patterns. These tumors have been mainly found in the soft tissue, bones and lungs in young patients[44], and only one case of TFE3-recombined EHE has been reported in the liver[45]. It was suggested that detection of the TFE3 rearrangement with TFE3 immunostaining may be a valuable tool for the differential diagnosis of EHE. The vascular marker ERG is also expressed in HEHE, but it is also expressed in other lesion types that need to be differentiated from HEHE, such as angiosarcoma and sclerosing hemangioma[35]. Keratin expression detected using a monoclonal antibody cocktail AE1/AE3 has been reported in 14%-31% of HEHE cases[39,43], but this marker is not very useful for diagnosis because it can be found both in EHE and rarely in intrasinusoidal cells.

DIAGNOSIS

Specific imaging features can be used as a reference for HEHE diagnosis, but histopathological examination still plays a decisive role in its diagnosis[46]. Fine needle aspiration and small biopsy followed by immunohistochemical staining of the collected sample is the most effective method for the diagnosis of HEHE[47]. However, a false negative rate of 10% was reported for puncture biopsy[48]. It was reported that biopsy pathology was focal nodular hyperplasia, and subsequent biopsy showed HEHE[49]. Pathological diagnosis of HEHE is based on the microscopic observation of a large number of proliferating dendritic or epithelial-like cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, immunohistochemical detection of CD31, CD34, or VIII-related antigen and occasionally mucus or fibrous stroma with endoplasmic vacuolization. Recent research has also attempted to identify an miRNA expression spectrum with the potential to become a new biological diagnostic tool[50].

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

HEHE should be distinguished from hepatic hemangioma, hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma and metastatic tumors by imaging or immunohistochemistry analysis (Table 1)[39,43,44]. Nuclear staining of CAMTA1 is helpful for differentiation of HEHE from hemangiosarcoma and angiosarcoma[39]. HRAS, KRAS, NRAS and PTPRB mutations can be seen in hepatic hemangiosarcoma. While the t (1; 3) (p36; q25) translocation leads to the EHE-specific fusion oncogene WWTR1–CAMTA1, only a small percentage of patients (6%) have been found to carry the YAP1–TFE3 fusion oncogene[43,44].

Table 1.

Clearly shows the differential diagnosis between hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma and other diseases

| Typical imaging features | Immunohistochemical staining markers | Molecular biology | |

| HEHE | Target sign, lollipop sign, capsular retraction | CD31, CD34, CD10, vimentin, Factor VIII antigen | Fusion gene: WWTR1-CAMTA1, YAP1-TFE3 |

| Angiosarcoma | Heterogeneous centripetal enhancement | CD31, CD34, Factor VIII antigen | HRAS, KRAS, NRAS and PTPRB mutation |

| HH | Posterior shadowing and centripetal filling | - | - |

| Cholangio carcinoma | Cholangiectasis, capsular retraction | Pan-cytokeratin | - |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Hyperechoic enhancement in the arterial phase and hypoechoic enhancement in the portal and delayed phases | HepPar-1; Pan-cytokeratin | - |

| Metastatic carcinoma | Bull's-eye sign | Pan-cytokeratin | - |

HEHE: Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma; HH: Hepatic hemangioma.

THERAPY

Because HEHE is rare, the ability to perform randomized controlled trials with multiple treatment strategies is limited, resulting the use of inconsistent treatments and even multiple operations[51]. At present, anti-angiogenic drugs, radiotherapy/chemotherapy, hepatectomy, liver transplantation (LT) as well as the observation and waiting strategy are applied in the treatment of HEHE[52]. In a study of patients treated from 1984 to 2005, LT accounted for the largest proportion of all treatments (44.8%), while non-treatment, chemotherapy or radiotherapy and partial hepatectomy were applied in 24.8%, 21% and 9.4% of cases, respectively[3]. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization also has been used to treat HEHE within the liver[53]. Surgical resection is considered to be the best treatment, especially for single small HEHE. LT is the ultimate treatment for multifocal, diffuse, non-resectable, recurrent tumors[20,54]. It has also been reported that for cases with a large HEHE tumor, the volume of the rest of the liver can be increased via embolization of the portal vein to ensure that the remaining liver volume after resection is sufficient[29]. The presence of metastasis is not a contraindication for LT[30]. In the study by Mehrabi et al[3], only 10% of cases had just a single lesion, and the 5-year survival rate for these cases was 75% after an initial treatment of hepatectomy[3]. In contrast, 81% of their patients had multiple lesions, and for these cases, LT has most often been the first choice of treatment. Rodriguez et al[54] reported a total of 110 HEHE patients who underwent LT between 1987 and 2005, and the 5-year survival rate for these patients was 64%, with 11% of them dying of recurrence within 5 years[54]. It is believed that successful hepatectomy or LT promotes long-term survival even in the presence of distal metastasis[55]. According to Fukuhara et al[56], it may be better to perform adjuvant therapy after LT in some aggressive cases and he claims that mTOR inhibitors are effective in preventing the recurrence and improving the survival rate after LT for hepatocellular carcinoma especially when the risk of recurrence was high. Ablation therapy also has a good effect on single and small HEHE, especially for marginal patients with malignant tumors[57].

Based on the rarity of HEHE, there is no standard drug strategy for treating it. Various chemotherapeutic drugs have been shown to be effective for HEHE, providing a promising treatment method. Given the vascular origin of HEHE and the detection of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors in EHE tumor cells, VEGF is believed to play a role in the growth of EHE. VEGF inhibitors, such as sorafinib[58,59], pazopanib[60], bevacizumab, and others, are known to play a role in the treatment of EHE. It was reported that the combination of the anti-VEGF drug bevacizumab and cell cycle inhibitor capecitabine achieved a good curative effect[19,61]. Other drugs such as mTOR inhibitors[56], thalidomide[62-64], pegylated liposomal doxorubicin[65], metronomic cyclophosphaide[66] and others have been introduced for the treatment of EHE and have acquired good results. For patients treated with pazopanib, Bally et al[60] proposed that the intratumoral changes observed on follow-up CT, such as a change in tumor density without obvious tumor contraction or calcification, can be regarded a strong indication of tumor response[60]. For patients with extrahepatic lesions, it has been reported that adjuvant chemotherapy may be an effective alternative therapy to prevent recurrence[67].

PROGNOSIS

Compared with other malignant liver tumors, HEHE has a good prognosis. One study reported that 50% of the patients survived more than 5 years without any treatment, and the presence of metastasis did not prolong or shorten the survival rate[68]. Still, in other studies, successful hepatectomy or LT was shown to promote long-term survival[3,69], with 1- and 3-year disease-free survival rates of 83.3% and 44.4% after hepatectomy, respectively, as well as 1- and 5-year survival rates of 100% and 75%, respectively. The corresponding 1- and 5-year survival rates after LT were 96% and 54.5%, respectively[70], which were lower than those after hepatectomy due to the presence of multiple tumors or infiltrated foci in these cases. According to the European Registry for LT, among 59 HEHE patients who received LT, the 1-, 5- and 10-year survival rates were 93%, 83% and 72%, respectively[49].

The HEHE-LT score was introduced for assessing the risk of HEHE recurrence after LT[71], and the 5-year disease-free survival rate was much higher for patients with a low score (2 or less) than for those with a high score (6 or more) (93.9% vs 38.5%, P < 0.001). The results corroborate the value of the score for evaluating the risk of recurrence after transplantation.

Tumors more than 10 cm in diameter and older age are also considered to be risk factors for a poor prognosis[19]. Moreover, macrovascular infiltration, a time to LT of at least 120 d and hilar lymph node infiltration are important risk factors for recurrence[71]. Okano et al[72] reported that the average diffusion coefficient map may be helpful in assessing the malignant potential of a tumor[72]. Deyrup et al[32] provided a risk stratification strategy based on the clinicopathological features of 49 patients with soft tissue EHE. They observed that high mitotic activity (> 3/50 high power fields) and a tumor size > 3 cm were associated with a worse prognosis[32], regardless of the anatomical site, cytological dysplasia or necrosis.

Finally, 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging can be applied to evaluate the degree of disease after anti-angiogenic drug therapy[27], given that most patients with a high cell tumor also have a poor prognosis. Dong et al[23] reported that the level of FDG uptake provides valuable information about the tumor cells, which may aid the predication of its clinical behavior[23].

CONCLUSION

HEHE is a low-to-moderate grade rare malignant tumor. Because its etiology and clinical manifestations remain unclear, it is necessary to differentiate it from other types of liver tumors based on immunohistochemical staining for the markers CD31, CD34, CD10, vimentin, and factor VIII antigen. In addition, the most common fusion oncogene is WWTR1–CAMTA1, with a few cases also showing YAP1–TFE3 expression. The treatment strategies that have been applied for HEHE are diverse, but surgical treatment remains the first choice, specifically LT or hepatectomy with lymph nodes dissection. For patients who are not fit for surgical treatment due to a bad physical condition, recurrence or metastasis, treatment with a VEGF inhibitor, such as sorafinib, pazopanib, or bevacizumab, or other chemotherapeutic drugs, including thalidomide, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, metronomic cyclophosphamide and others, can be used as adjuvant chemotherapy or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The HEHE-LT score should be used to assess the risk of recurrence after LT, and close follow-up is necessary.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests to disclose.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: July 6, 2020

First decision: August 8, 2020

Article in press: August 22, 2020

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tahara H S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

Contributor Information

Kai Kou, Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Yu-Guo Chen, Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Jian-Peng Zhou, Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Xiao-Dong Sun, Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Da-Wei Sun, Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Shu-Xuan Li, Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China.

Guo-Yue Lv, Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China. kouxiuyangming@qq.com.

References

- 1.Moulai N, Chavanon O, Guillou L, Noirclerc M, Blin D, Brambilla E, Lantuejoul S. Atypical primary epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the heart. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:188–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elleuch N, Dahmani W, Aida Ben S, Jaziri H, Aya H, Ksiaa M, Jmaa A. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: A misdiagnosed rare liver tumor. Presse Med. 2018;47:182–185. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2017.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrabi A, Kashfi A, Fonouni H, Schemmer P, Schmied BM, Hallscheidt P, Schirmacher P, Weitz J, Friess H, Buchler MW, Schmidt J. Primary malignant hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: a comprehensive review of the literature with emphasis on the surgical therapy. Cancer. 2006;107:2108–2121. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishak KG, Sesterhenn IA, Goodman ZD, Rabin L, Stromeyer FW. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver: a clinicopathologic and follow-up study of 32 cases. Hum Pathol. 1984;15:839–852. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(84)80145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonescu C. Malignant vascular tumors--an update. Mod Pathol. 2014;27 Suppl 1:S30–S38. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruegel M, Muenzel D, Waldt S, Specht K, Rummeny EJ. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: findings at CT and MRI including preliminary observations at diffusion-weighted echo-planar imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36:415–424. doi: 10.1007/s00261-010-9641-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurung S, Fu H, Zhang WW, Gu YH. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma metastasized to the peritoneum, omentum and mesentery: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5883–5889. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Earnest F 4th, Johnson CD. Case 96: Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Radiology. 2006;240:295–298. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2401032099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blachar A, Federle MP, Brancatelli G. Hepatic capsular retraction: spectrum of benign and malignant etiologies. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:690–699. doi: 10.1007/s00261-001-0094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamone G, Miraglia R. The "Target sign" and the "Lollipop sign" in hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2019;44:1617–1620. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1820-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neofytou K, Chrysochos A, Charalambous N, Dietis M, Petridis C, Andreou C, Petrou A. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma and the danger of misdiagnosis: report of a case. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:243939. doi: 10.1155/2013/243939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mistry AM, Gorden DL, Busler JF, Coogan AC, Kelly BS. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:521–525. doi: 10.1007/s12029-012-9389-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou L, Cui MY, Xiong J, Dong Z, Luo Y, Xiao H, Xu L, Huang K, Li ZP, Feng ST. Spectrum of appearances on CT and MRI of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:69. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0299-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim KH, Kim SJ, Lee SH. Living-Donor Liver Transplantation for Hepatic Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma with Early Recurrence in an Adult: A Case Report. Transplantation. 2018;102:S905–S905. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang JW, Li Y, Xie K, Dong W, Cao XT, Xiao WD. Spontaneous rupture of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: A case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:185–190. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afrit M, Nasri M, Labidi S, Mejri N, El Benna H, Boussen H. Aggressive primary hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: a case report and literature review. Cancer Biol Med. 2017;14:187–190. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2016.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong Y, Wang WP, Cantisani V, D'Onofrio M, Ignee A, Mulazzani L, Saftoiu A, Sparchez Z, Sporea I, Dietrich CF. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of histologically proven hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4741–4749. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i19.4741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ling WW, Luo Y, Lin L, Ma L, Qiu TT, Yang LL, Lu Q. [Ultrasonographic Features of Hepatic Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma on B-mode and Contrast-enhanced Ultrasound] Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2017;48:595–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Treska V, Daum O, Svajdler M, Liska V, Ferda J, Baxa J. Hepatic Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma - a Rare Tumor and Diagnostic Dilemma. In Vivo. 2017;31:763–767. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gan LU, Chang R, Jin H, Yang LI. Typical CT and MRI signs of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:1699–1706. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paolantonio P, Laghi A, Vanzulli A, Grazioli L, Morana G, Ragozzino A, Colagrande S. MRI of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (HEH) J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40:552–558. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alomari AI. The lollipop sign: a new cross-sectional sign of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:460–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong A, Dong H, Wang Y, Gong J, Lu J, Zuo C. MRI and FDG PET/CT findings of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38:e66–e73. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318266ceca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YJ, Yun M, Lee WJ, Kim KS, Lee JD. Usefulness of 18F-FDG PET in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:1467–1472. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitapci MT, Akkaş BE, Gullu I, Sokmensuer C. FDG-PET/CT in the evaluation of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver: the role of dual-time-point imaging. A case presentation and review of the literature. Ann Nucl Med. 2010;24:549–553. doi: 10.1007/s12149-010-0379-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suga K, Kawakami Y, Hiyama A, Hori K. F-18 FDG PET/CT monitoring of radiation therapeutic effect in hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Clin Nucl Med. 2009;34:199–202. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181966f45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giancipoli RG, Monti S, Basturk O, Klimstra D, Keohan ML, Schillaci O, Corrias G, Sawan P, Mannelli L. Complete metabolic response to therapy of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma evaluated with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/contrast-enhanced computed tomography: A CARE case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e12795. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JH, Jeong WK, Kim YK, Lee WJ, Ha SY, Kim KW, Kim J. Magnetic resonance findings of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: emphasis on hepatobiliary phase using Gd-EOB-DTPA. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2017;42:2261–2271. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makhlouf HR, Ishak KG, Goodman ZD. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver: a clinicopathologic study of 137 cases. Cancer. 1999;85:562–582. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990201)85:3<562::aid-cncr7>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Remiszewski P, Szczerba E, Kalinowski P, Gierej B, Dudek K, Grodzicki M, Kotulski M, Paluszkiewicz R, Patkowski W, Zieniewicz K, Krawczyk M. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver as a rare indication for liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11333–11339. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i32.11333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss SW, Ishak KG, Dail DH, Sweet DE, Enzinger FM. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma and related lesions. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1986;3:259–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deyrup AT, Tighiouart M, Montag AG, Weiss SW. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of soft tissue: a proposal for risk stratification based on 49 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:924–927. doi: 10.1097/pas.0b013e31815bf8e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Illueca C, Machado I, García A, Covisa A, Morales J, Cruz J, Traves V, Almenar S. Uncommon vascular tumor of the ovary. Primary ovarian epithelioid hemangioendothelioma or vascular sarcomatous transformation in ovarian germ cell tumor? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:1589–1591. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-2036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi KH, Moon WS. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2013;19:315–319. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2013.19.3.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujii T, Zen Y, Sato Y, Sasaki M, Enomae M, Minato H, Masuda S, Uehara T, Katsuyama T, Nakanuma Y. Podoplanin is a useful diagnostic marker for epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:125–130. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu HJ, Jin YW, Jing QY, Shrestha A, Cheng NS, Li FY. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: Dilemma and challenges in the preoperative diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:9247–9250. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i41.9247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sardaro A, Bardoscia L, Petruzzelli MF, Portaluri M. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: an overview and update on a rare vascular tumor. Oncol Rev. 2014;8:259. doi: 10.4081/oncol.2014.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong K, Wang XX, Feng JL, Liu H, Zu KJ, Chang J, Lv FD. Pathological characteristics of liver biopsies in eight patients with hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:11015–11023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doyle LA, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. Nuclear Expression of CAMTA1 Distinguishes Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma From Histologic Mimics. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:94–102. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shibuya R, Matsuyama A, Shiba E, Harada H, Yabuki K, Hisaoka M. CAMTA1 is a useful immunohistochemical marker for diagnosing epithelioid haemangioendothelioma. Histopathology. 2015;67:827–835. doi: 10.1111/his.12713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendlick MR, Nelson M, Pickering D, Johansson SL, Seemayer TA, Neff JR, Vergara G, Rosenthal H, Bridge JA. Translocation t(1;3)(p36.3;q25) is a nonrandom aberration in epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:684–687. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200105000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Errani C, Zhang L, Sung YS, Hajdu M, Singer S, Maki RG, Healey JH, Antonescu CR. A novel WWTR1-CAMTA1 gene fusion is a consistent abnormality in epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of different anatomic sites. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50:644–653. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flucke U, Vogels RJ, de Saint Aubain Somerhausen N, Creytens DH, Riedl RG, van Gorp JM, Milne AN, Huysentruyt CJ, Verdijk MA, van Asseldonk MM, Suurmeijer AJ, Bras J, Palmedo G, Groenen PJ, Mentzel T. Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma: clinicopathologic, immunhistochemical, and molecular genetic analysis of 39 cases. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:131. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Antonescu CR, Le Loarer F, Mosquera JM, Sboner A, Zhang L, Chen CL, Chen HW, Pathan N, Krausz T, Dickson BC, Weinreb I, Rubin MA, Hameed M, Fletcher CD. Novel YAP1-TFE3 fusion defines a distinct subset of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52:775–784. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuo FY, Huang HY, Chen CL, Eng HL, Huang CC. TFE3-rearranged hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma-a case report with immunohistochemical and molecular study. APMIS. 2017;125:849–853. doi: 10.1111/apm.12716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller WJ, Dodd GD, 3rd, Federle MP, Baron RL. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver: imaging findings with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:53–57. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.1.1302463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campione S, Cozzolino I, Mainenti P, D'Alessandro V, Vetrani A, D'Armiento M. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: Pitfalls in the diagnosis on fine needle cytology and "small biopsy" and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract. 2015;211:702–705. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Venkatesh SK, Chandan V, Roberts LR. Liver masses: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic perspective. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1414–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lerut JP, Orlando G, Adam R, Schiavo M, Klempnauer J, Mirza D, Boleslawski E, Burroughs A, Sellés CF, Jaeck D, Pfitzmann R, Salizzoni M, Söderdahl G, Steininger R, Wettergren A, Mazzaferro V, Le Treut YP, Karam V European Liver Transplant Registry. The place of liver transplantation in the treatment of hepatic epitheloid hemangioendothelioma: report of the European liver transplant registry. Ann Surg. 2007;246:949–57; discussion 957. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815c2a70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morishita A, Iwama H, Yoneyama H, Sakamoto T, Fujita K, Nomura T, Tani J, Miyoshi H, Fujihara S, Nishiyama N, Kobara H, Mori H, Yamamoto N, Okano K, Suzuki Y, Ibuki E, Haba R, Himoto T, Masaki T. MicroRNA profile of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:1655–1659. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Emamaullee JA, Nowak K, Beach M, Bacani J, Shapiro AMJ. Hepatic Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma Presenting as an Enlarging Vascular Lesion within the Spleen. Case Rep Transplant. 2018;2018:3948784. doi: 10.1155/2018/3948784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weitz J, Klimstra DS, Cymes K, Jarnagin WR, D'Angelica M, La Quaglia MP, Fong Y, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH, Dematteo RP. Management of primary liver sarcomas. Cancer. 2007;109:1391–1396. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cardinal J, de Vera ME, Marsh JW, Steel JL, Geller DA, Fontes P, Nalesnik M, Gamblin TC. Treatment of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: a single-institution experience with 25 cases. Arch Surg. 2009;144:1035–1039. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodriguez JA, Becker NS, O'Mahony CA, Goss JA, Aloia TA. Long-term outcomes following liver transplantation for hepatic hemangioendothelioma: the UNOS experience from 1987 to 2005. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:110–116. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Madariaga JR, Marino IR, Karavias DD, Nalesnik MA, Doyle HR, Iwatsuki S, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. Long-term results after liver transplantation for primary hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1995;2:483–487. doi: 10.1007/BF02307080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fukuhara S, Tahara H, Hirata Y, Ono K, Hamaoka M, Shimizu S, Hashimoto S, Kuroda S, Ohira M, Ide K, Kobayashi T, Ohdan H. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma successfully treated with living donor liver transplantation: A case report and literature review. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:108–115. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamarajah SK, Robinson D, Littler P, White SA. Small, incidental hepatic epithelioid haemangioendothelioma the role of ablative therapy in borderline patients. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy223. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjy223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sangro B, Iñarrairaegui M, Fernández-Ros N. Malignant epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver successfully treated with Sorafenib. Rare Tumors. 2012;4:e34. doi: 10.4081/rt.2012.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chevreau C, Le Cesne A, Ray-Coquard I, Italiano A, Cioffi A, Isambert N, Robin YM, Fournier C, Clisant S, Chaigneau L, Bay JO, Bompas E, Gauthier E, Blay JY, Penel N. Sorafenib in patients with progressive epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: a phase 2 study by the French Sarcoma Group (GSF/GETO) Cancer. 2013;119:2639–2644. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bally O, Tassy L, Richioud B, Decouvelaere AV, Blay JY, Derbel O. Eight years tumor control with pazopanib for a metastatic resistant epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2015;5:12. doi: 10.1186/s13569-014-0018-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lau A, Malangone S, Green M, Badari A, Clarke K, Elquza E. Combination capecitabine and bevacizumab in the treatment of metastatic hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2015;7:229–236. doi: 10.1177/1758834015582206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raphael C, Hudson E, Williams L, Lester JF, Savage PM. Successful treatment of metastatic hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma with thalidomide: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:413. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mascarenhas RC, Sanghvi AN, Friedlander L, Geyer SJ, Beasley HS, Van Thiel DH. Thalidomide inhibits the growth and progression of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Oncology. 2004;67:471–475. doi: 10.1159/000082932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salech F, Valderrama S, Nervi B, Rodriguez JC, Oksenberg D, Koch A, Smok G, Duarte I, Pérez-Ayuso RM, Jarufe N, Martínez J, Soza A, Arrese M, Riquelme A. Thalidomide for the treatment of metastatic hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: a case report with a long term follow-up. Ann Hepatol. 2011;10:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grenader T, Vernea F, Reinus C, Gabizon A. Malignant epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver successfully treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e722–e724. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lakkis Z, Kim S, Delabrousse E, Jary M, Nguyen T, Mantion G, Heyd B, Lassabe C, Borg C. Metronomic cyclophosphamide: an alternative treatment for hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. J Hepatol. 2013;58:1254–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tan Y, Yang X, Dong C, Xiao Z, Zhang H, Wang Y. Diffuse hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma with multiple splenic metastasis and delayed multifocal bone metastasis after liver transplantation on FDG PET/CT images: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e10728. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Llueca A, Piquer D, Maazouzi Y, Medina C, Delgado K, Serra A, Escrig J. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: A great mimicker. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;53:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baek SH, Yoon JH. Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings of a Malignant Hepatic Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma: A Rare Case of Solitary Small Nodular Form. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2013;1:2324709613504549. doi: 10.1177/2324709613504549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jung DH, Hwang S, Hong SM, Kim KH, Lee YJ, Ahn CS, Moon DB, Ha TY, Song GW, Park GC, Yu E, Lee SG. Clinicopathological Features and Prognosis of Hepatic Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma After Liver Resection and Transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2016;21:784–790. doi: 10.12659/aot.901172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lai Q, Feys E, Karam V, Adam R, Klempnauer J, Oliverius M, Mazzaferro V, Pascher A, Remiszewski P, Isoniemi H, Pirenne J, Foss A, Ericzon BG, Markovic S, Lerut JP European Liver Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA) Hepatic Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma and Adult Liver Transplantation: Proposal for a Prognostic Score Based on the Analysis of the ELTR-ELITA Registry. Transplantation. 2017;101:555–564. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Okano H, Nakajima H, Tochio T, Suga D, Kumazawa H, Isono Y, Tanaka H, Matsusaki S, Sase T, Saito T, Mukai K, Nishimura A, Matsushima N, Baba Y, Murata T, Hamada T, Taoka H. A case of a resectable single hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma with characteristic imaging by ADC map. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2015;8:406–413. doi: 10.1007/s12328-015-0604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]