Abstract

BACKGROUND

A previously healthy 22-year-old woman presented with abdominal pain and jaundice. She had a reagent antinuclear factor (1:640, with a homogeneous nuclear pattern) and hypergammaglobulinemia (2.16 g/dL). Anti-smooth muscle, anti-mitochondrial and anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody type 1 antibodies were negative. Magnetic resonance cholangiography showed a cirrhotic liver with multiple focal areas of strictures of the intrahepatic bile ducts, with associated dilations. Liver biopsy demonstrated periportal necroinflammatory activity, plasmocyte infiltration and advanced fibrosis. Colonoscopy showed ulcerative pancolitis and mild activity (Mayo score 1), with a spared rectum. Treatment with corticosteroids, azathioprine, ursodeoxycholic acid and mesalamine was initiated, with improvement in laboratory tests. The patient was referred for a liver transplantation evaluation.

AIM

To report the case of a female patient with autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) overlap syndrome associated with ulcerative colitis and to systematically review the available cases of autoimmune hepatitis and PSC overlap syndrome.

METHODS

In accordance with preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis protocols guidelines, retrieval of studies was based on medical subject headings and health sciences descriptors, which were combined using Boolean operators. Searches were run on the electronic databases Scopus, Web of Science, MEDLINE (PubMed), Biblioteca Regional de Medicina, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, Cochrane Library for Systematic Reviews and Opengray.eu. Languages were restricted to English, Spanish and Portuguese. There was no date of publication restrictions. The reference lists of the studies retrieved were searched manually.

RESULTS

The search strategy retrieved 3349 references. In the final analysis, 44 references were included, with a total of 109 cases reported. The most common clinical finding was jaundice and 43.5% of cases were associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Of these, 27.6% were cases of Crohn’s disease, 68% of ulcerative colitis, and 6.4% of indeterminate colitis. Most patients were treated with steroids. All-cause mortality was 3.7%.

CONCLUSION

PSC and autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome is generally associated with inflammatory bowel disease and has low mortality and good response to treatment.

Keywords: Autoimmune hepatitis, Primary sclerosing cholangitis, Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, Inflammatory bowel diseases

Core Tip: We report the case of a female patient with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) overlap syndrome associated with ulcerative colitis and systematically review the available cases of AIH and PSC overlap syndrome. A previously healthy 22-year-old woman presented with abdominal pain and jaundice. She had a reagent antinuclear factor (1:640, with a homogeneous nuclear pattern). Magnetic resonance cholangiography showed a cirrhotic liver with multiple focal areas of strictures of the intrahepatic bile ducts, with associated dilations. Liver biopsy demonstrated periportal necroinflammatory activity, plasmocyte infiltration, and advanced fibrosis. Colonoscopy showed ulcerative pancolitis and mild activity (Mayo score 1), with a spared rectum. Treatment with corticosteroids, azathioprine, ursodeoxycholic acid and mesalamine was initiated, with improvement in laboratory tests. Searches for systematic reviews were run on seven electronic databases, retrieving 3349 references. In the final analysis, 44 references were included, with a total of 109 cases reported. The most common clinical finding was jaundice and 43.5% of cases were associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Of these, 27.6% were cases of Crohn’s disease, 68% of ulcerative colitis, and 6.4% of indeterminate colitis. Most patients were treated with steroids. All-cause mortality was 3.7%. In conclusion, PSC and AIH overlap syndrome is generally associated with inflammatory bowel disease and has low mortality and good response to treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a progressive disorder that causes inflammation and scarring of bile ducts, leading to fibrosis, strictures and dilatation of the biliary tree. These abnormalities are usually identified using cholangiography techniques such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. An exception to this can occur in patients presenting with a rare variant form of PSC called small duct PSC, in which cholangiography findings are absent. The etiology and pathogenesis of PSC are currently unknown, although PSC is highly associated with the presence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[1].

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic inflammatory liver disease with specific laboratory and histological findings. It is characterized by elevated serum aminotransferases, increased total immunoglobulin G (IgG) and positive autoantibodies, whereas liver biopsy may show interface hepatitis and portal mononuclear cell infiltrate[2]. In some cases, patients may present with variant forms of AIH, in which there is an overlap of AIH and another autoimmune liver disease, such as PSC. Therefore, PSC/AIH overlap syndrome (OS) is a rare disorder characterized by the concomitant occurrence of the biochemical and histological features of AIH and the cholangiography abnormalities found in PSC.

In this paper, we report the case of a female patient with PSC/AIH OS associated with ulcerative colitis (UC) and systematically review the literature for available cases of this association.

Case report

A previously healthy 22-year-old woman sought medical care due to abdominal pain, jaundice, choluria and acholia that had begun a week before with progressive worsening. There was no report of associated weight loss. She was using oral contraceptives only and denied alcoholism, smoking and drug use.

Laboratory examinations showed hyperbilirubinemia (12.3 mg/dL) with an elevation of direct bilirubin (10 mg/dL), an increase in gamma-glutamyltransferase (165 U/L) and an increase in aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase (408 U/L and 277 U/L, respectively). The liver function tests were normal. Serology for hepatitis A, B, C and human immunodeficiency viruses was negative, and IgM serology for cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr, and herpes simplex was also negative.

Abdominal ultrasound was performed and the liver showed a diffuse micronodular pattern. Workup was continued through autoimmune markers, urinary copper, serum ceruloplasmin, serum ferritin, transferrin saturation index, and upper abdominal magnetic resonance imaging. The examinations showed a reagent antinuclear factor (1:640, with a homogeneous nuclear pattern) and protein electrophoresis showed hypergammaglobulinemia (2.16 g/dL). Anti-smooth muscle, anti-mitochondrial antibody, and liver-kidney microsomal antibody type 1 were negative.

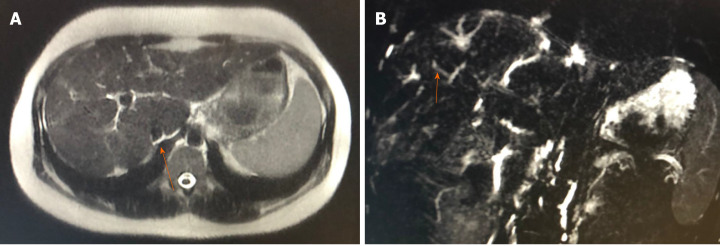

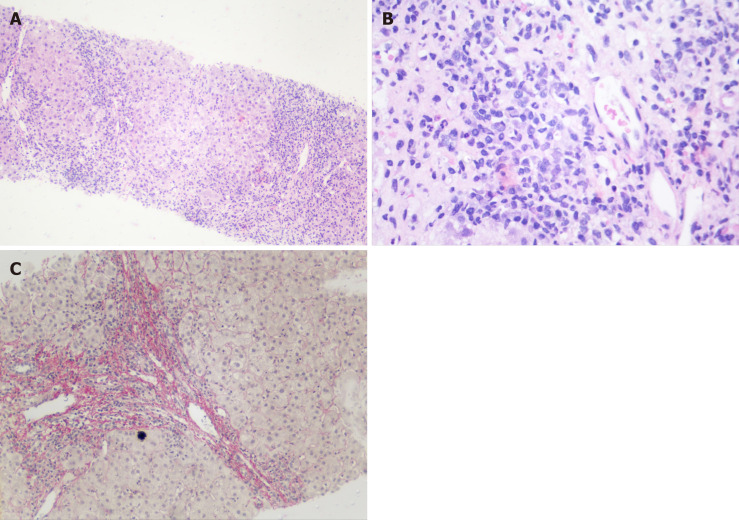

Magnetic resonance cholangiography showed a reduced-sized liver suggestive of cirrhosis and multiple focal areas of strictures of the intrahepatic bile ducts, with associated dilations (Figure 1). Cholangiography suggested the diagnosis of PSC associated with cirrhosis, and the patient underwent an ultrasound-guided liver biopsy, which showed periportal necroinflammatory activity, plasmocyte infiltration, and advanced fibrosis (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance cholangiography. A: Reduced-sized liver, with lobulated contours and blunt edges, showing caudate lobe hypertrophy and volumetric reduction of the right lobe periphery; B: Multiple focal areas of caliber reduction in the intrahepatic bile duct, with upstream biliary ectasia, associated with signs of distortion of the usual architecture and parietal irregularities in the bile duct.

Figure 2.

Liver biopsy. A: Intense increase in periportal necroinflammatory activity (Hematoxylin-eosin staining 40 ×); B: Grouping of periportal plasmocyte cells (Hematoxylin-eosin staining 100 ×); and C: Fibrosis in red demarking a nodule (Picro Sirius Red 100 ×).

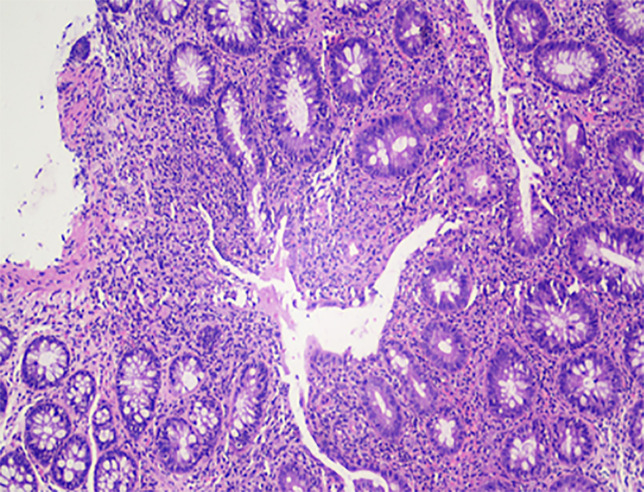

The patient also underwent colonoscopy and endoscopy. Endoscopy did not show esophageal varices and colonoscopy showed changes suggestive of ulcerative pancolitis with mild activity (Mayo score 1), with a spared rectum (Figure 3). Treatment with corticosteroids, azathioprine, ursodeoxycholic acid and mesalamine was initiated, with improvement in laboratory tests, culminating in the normalization of liver transaminases and bilirubin. The patient was referred for a liver transplantation evaluation.

Figure 3.

Ascending colon, biopsy. Area of erosion in the ascending colon (Hematoxylin-eosin staining 100 ×).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations contained in the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis protocols guidelines. Our systematic review was registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews, maintained by York University (registration number CRD42020160708).

Data sources

Studies were retrieved using the terms described in the appendix. Searches were run on the electronic databases Scopus, Web of Science, Medline (PubMed), Biblioteca Regional de Medicina, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, Cochrane Library for Systematic Reviews and Opengray.eu. Languages were restricted to English, Spanish and Portuguese. There was no date of publication restrictions. The reference lists of the retrieved studies were also searched manually. The databases were searched in December 2019.

Inclusion criteria and outcomes

Inclusion criteria were clinical case reports or case series involving AIH and PSC. Exclusion criteria were studies other than case reports or case series and articles that were not related to the topic. If there was more than one study published using the same case, the variables were complemented with both articles. Studies published only as abstracts were included, as long as the data available made data collection possible. The outcome measured was recovery or death.

Study selection and data extraction

The search terms used for each database are described in the appendix. An initial screening of titles and abstracts was the first stage to select potentially relevant papers. The second step was the analysis of full-length papers. In this step, some studies were removed due to lack of clinical information. Two independent reviewers (VB, LB) extracted data using a standardized data extraction form after assessing and reaching a consensus on eligible studies. The same reviewers separately assessed each study and extracted data on the characteristics of the subjects and the outcomes measured. A third party (JS) was responsible for divergences in study selection and data extraction, clearing them when required.

Statistical analysis

Data are summarized using descriptive analysis–frequency, means and median, using RStudio.

RESULTS

Systematic review

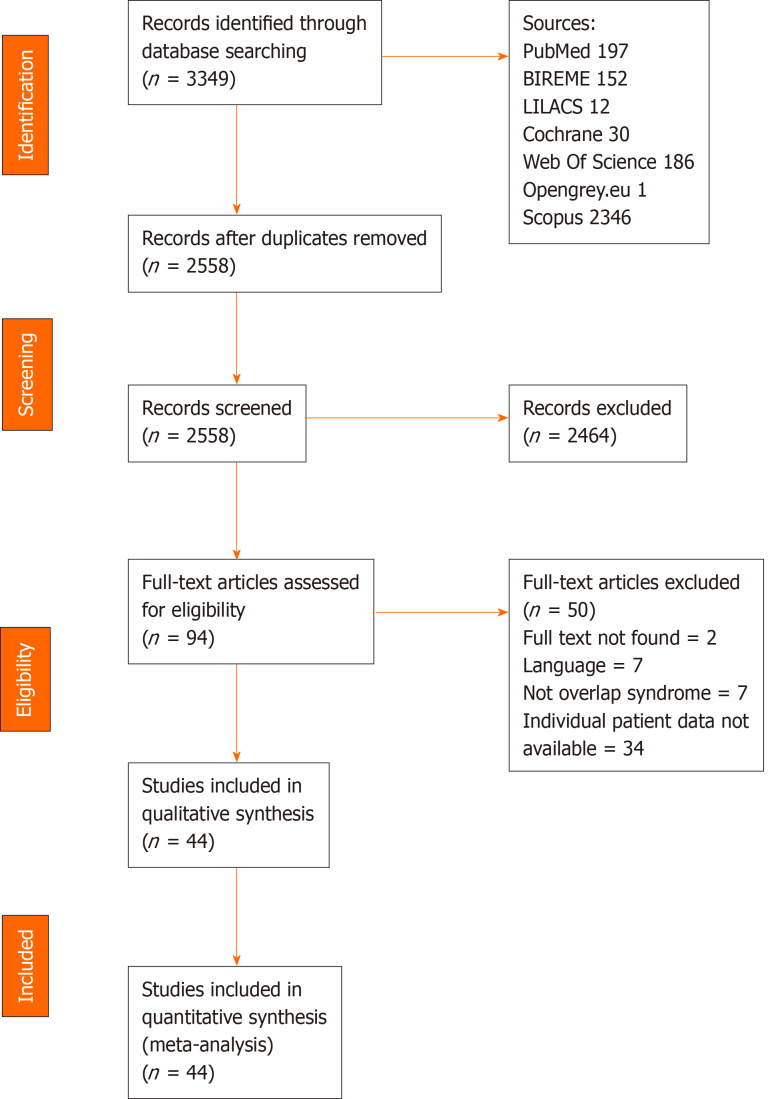

Using the search strategy, 3349 references were found and 791 references were excluded as they were duplicates. After analyzing the titles and abstracts, 2119 references were excluded and 86 full-text papers were analyzed. In the final analysis, 44 references were included, including 109 cases. A flowchart illustrating the search strategy is shown in Figure 4. The studies included were either a case report or a case series.

Figure 4.

Prisma flowchart.

Cases from Germany, the United States of America, Czech Republic, Netherlands and Italy were the most common (20.3%, 13.9%, 10.2%, 8.3% and 7.4%, respectively). The baseline features are shown in Table 1. A total of 109 patients were included, 46 (42.59%) were male. Data regarding the sex of 26 patients (24.07%) were not available. All patients were diagnosed with PSC/AIH OS. The age range was 2 to 72 years (mean age was 25 years). Forty-eight (44.44%) patients had IBD. Of these, 13 (27.65%) had Crohn’s disease, 32 (68.08%) had UC and 3 (6.38%) had indeterminate colitis. Only 37 (34.25%) patients did not have IBD, and in 24 (22.22%) the data were NA.

Table 1.

Baseline features in 109 patients with overlap syndrome (primary sclerosing cholangitis/autoimmune hepatitis)

| Variable | Patients (n = 109) |

| Mean age (yr) | 25.52 |

| Sex (male) | 46 (42.59%) |

| Race | 10 (6.78%) |

| White | 7 (70%) |

| Black | 3 (30%) |

| IBD | 48 (44.44%) |

| CD | 13 (27.65%) |

| UC | 32 (68.08%) |

| Non-specific | 3 (6.38%) |

| PSC | |

| Small Ducts | 4 (3.70%) |

| AIH (median) | |

| SAH pre-treatment (pts) | 17 (13-22) |

| SAH post-treatment (pts) | 19 (13-25) |

| Clinical presentation | |

| Fever | 7 (6.48%) |

| Dyspnea | 1 (0.93%) |

| Headache | 1 (0.93%) |

| Jaundice | 31 (28.70%) |

| Pruritus | 11 (10.19%) |

| Urine alteration | 6 (5.55%) |

| Choluria | 5 (83.33%) |

| Hematuria | 1 (16.66%) |

| Nausea | 4 (3.70%) |

| Emesis | 8 (7.40%) |

| Without blood | 4 (50%) |

| Hematemesis | 4 (50%) |

| Diarrhea | 11 (10.19%) |

| Stools | 18 (16.66%) |

| Hematochezia | 1 (5.55%) |

| Melena | 1 (5.55%) |

| Incontinence | 1 (5.55%) |

| Acholia | 3 (16.66%) |

| Watery stools | 11 (61.11%) |

| Steatorrhea | 1 (5.55%) |

| Abdominal pain | 21 (19.44%) |

| Joint pain | 2 (1.85%) |

| Weight loss | 9 (8.33%) |

| Fatigue | 22 (20.37%) |

| Family history | 4 (3.70%) |

| Hepatomegaly | 15 (13.89%) |

| Splenomegaly | 12 (11.11%) |

| Ascites | 7 (6.48%) |

| Fecal occult blood | 3 (2.78%) |

| Cirrhosis | 17 (15.74%) |

| Encephalopathy | 2 (1.85%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Esophageal varices | 13 (12.03%) |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 (0.93%) |

| Anemia | 1 (0.93%) |

| Alcohol-induced pancreatitis | 1 (0.93%) |

| Hepatic insufficiency | 1 (0.93%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 (0.93%) |

| Smoker | 1 (0.93%) |

| Membranous glomerulonephritis | 1 (0.93%) |

| Hepatocarcinoma | 1 (0.93%) |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 1 (0.93%) |

| Reflux nephropathy | 1 (0.93%) |

| Post-infantile giant cell hepatitis | 4 (3.70%) |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 1 (0.93%) |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 1 (0.93%) |

| Biopsy | 109 (100%) |

| Grade (Batts-Ludwig) | 29 (26.85%) |

| None | 2 (6.89%) |

| Minimal | 1 (3.44%) |

| Mild | 10 (34.48%) |

| Moderate | 11 (37.93%) |

| Severe | 5 (17.24%) |

| Stage (Batts-Ludwig) | 37 (34.25%) |

| None | 1 (2.70%) |

| Portal fibrosis | 14 (37.83%) |

| Periportal fibrosis | 10 (27.02%) |

| Septal fibrosis | 9 (24.32%) |

| Cirrhosis | 3 (8.10%) |

| Laboratory tests (mean) | |

| Hb (g/dL) | 10.20 |

| Ht (%) | 32.8 |

| Leucocytes (mm3) (median) | 7600 |

| Platelets (mm3) (median) | 185000 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 15.35 |

| INR | 1.41 |

| ALT (U/L) | 378.2 |

| AST (U/L) | 378.2 |

| GGT (U/L) | 316.6 |

| ALP (U/L) | 693.4 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 5.14 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 4.43 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 17.82 |

| Albumin (g/dL) (median) | 3.09 |

| Total globulins (mg/L) | 51410 |

| IgG total (mg/dL) | 2762 |

| IgA total (mg/dL) | 230.3 |

| IgM total (mg/dL) | 729.7 |

| Antibodies | |

| LKM1 | 3 (2.78%) |

| AMA | 3 (2.78%) |

| ANA | 59 (54.63%) |

| SMA | 33 (30.56%) |

| pANCA | 36 (33.33%) |

| HLA | 18 (16.66%) |

| Medications | 63 (58.33%) |

| Steroids | 62 (98.41%) |

| Azathioprine | 48 (76.19%) |

| 6-mercaptopurine | 1 (1.58%) |

| Ursodeoxycholic acid | 47 (74.60%) |

| Mesalazine | 7 (11.11%) |

| Antibiotics | 3 (4.76%) |

| D-penicillamine | 1 (1.58%) |

| Cyclosporine A | 1 (1.58%) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 2 (3.17%) |

| Clinical improvement | 61 (56.48%) |

| Relapse | 41 (37.96%) |

| Transplantation | 13 (12.87%) |

| Mean time from diagnosis-transplant (mo), n = 10 (76.92%) | 74.90 |

| Transplant medications, n = 4 | 4 (30.76%) |

| Steroids | 4 (100%) |

| Basiliximab | 1 (25%) |

| Cyclosporine | 2 (50%) |

| Azathioprine | 1 (25%) |

| Tacrolimus | 2 (50%) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 2 (50%) |

| Mean time follow-up (mo) | 59.18 |

| Death | 4 (3.70%) |

IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; CD: Crohn’s disease; UC: Ulcerative colitis; PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis; AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; SAH: Score for autoimmune hepatitis; INR: International normalized ratio; ALT: Alanine transaminase; AST: Aspartate transaminase; GGT: Gamma-glutamyl transferase; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; LKM1: Liver kidney microsome type 1 antibody; AMA: Anti-mitochondrial antibodies; ANA: Antinuclear antibody; SMA: Smooth muscle antibodies; pANCA: Perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies.

The most common clinical presentation was jaundice, which was present in 31 (28.70%) cases, followed by fatigue and abdominal pain (20.37% and 19.44%, respectively). Hepatomegaly was present in 15 (13.89%) patients and 12 (11.11%) patients had splenomegaly. PSC was identified in small and large ducts (3.70% and 81.48%, respectively). The median score for autoimmune hepatitis was 17 (13-22) pretreatment, and post-treatment was 19 (13-25). Liver biopsy was performed in all patients, and some were classified using the Batts-Ludwig system for grading and staging hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. Cirrhosis was found in 17 (15.74%) patients during follow-up; 2 patients had encephalopathy; 13 (12.03%) patients had esophageal varices; 4 (3.70%) with post-infantile giant cell hepatitis; and only 1 with hepatocarcinoma. Laboratory tests and antibodies are described in Table 1. Human leukocyte antigen and a summary of the clinical cases are described in Table 2[3-46].

Table 2.

Summary of systematically reviewed clinical cases (primary sclerosing cholangitis/autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome)

| Ref. | Country | Sex | Age | Clinical presentation | IBD | Co-morbidities | Antibodies | HLA | Treatment | Relapse | Outcome | Miscellaneous |

| Wurbs et al[3], 1995 | Germany | F | 28 | Fever, Choluria, Weight Loss, Fatigue | N | None | pANCA, SMA | DR | Steroids, AZA | N | Recovery | |

| Lawrence et al[4], 1994 | United States | M | 39 | Nausea, Emesis, Fatigue, Hepatomegaly, Occult stool blood | UC | Cirrhosis | SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, Cyclosporine A | N | Recovery | |

| Nalepa et al[5], 2017 | Poland | M | 10 | Jaundice, Diarrhea, Abdominal Pain, Hepatomegaly, Splenomegaly, Ascites, Hematemesis | UC | Cirrhosis, Esophageal Varices | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA, MSM | Y | Recovery | Liver transplantation |

| Luketic et al[6], 1997 | United States | F | 38 | Jaundice, Nausea, Fatigue, Ascites, Hematemesis | N | None | ANA | NA | Steroids, AZA | Y | Recovery | Liver transplantation |

| Mueller et al[7], 2018 | Germany | F | 15 | Vomiting, Fatigue | N | None | ANA, pANCA, SMA, AMA | NA | Steroids, UDCA | N | Recovery | |

| Guerrero-Hernández et al[8], 2007 | Mexico | F | 22 | Jaundice, Choluria, Fatigue | N | None | ANA, pANCA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | N | Recovery | |

| Takiguchi et al[9], 2002 | Japan | F | 36 | Fever | N | None | ANA, pANCA | A24, A31, B35, B61, Cw4, DR4 | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | |

| McNair et al[10], 1998 | United Kingdom | M | 38 | Jaundice, Watery Stools, Abdominal Pain, Weight Loss | UC | Encephalopathy | ANA, LKM1, pANCA, SMA | B8, DR3 | Steroids, AZA | Y | Death | |

| McNair et al[10], 1998 | United Kingdom | F | 20 | Jaundice, Itching | N | None | ANA, pANCA, SMA | ND | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | |

| McNair et al[10], 1998 | United Kingdom | M | 26 | Dyspnea, Jaundice | N | None | ANA, pANCA | A1, B8, DR3 | Steroids, AZA | Y | Recovery | |

| McNair et al[10], 1998 | United Kingdom | M | 14 | Jaundice, Diarrhea, Abdominal Pain | UC | None | ANA, pANCA, SMA | A1, B8, DR3 | Steroids, AZA | Y | Recovery | |

| McNair et al[10], 1998 | United Kingdom | M | 18 | Jaundice, Diarrhea, Abdominal Pain, Weight Loss | N | None | pANCA, SMA | ND | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | N | Recovery | |

| Man et al[11], 2017 | Romania | M | 13 | Jaundice, Hepatomegaly, Splenomegaly | N | Esophageal Varices | SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA, Mycophenolate Mofetil | Y | Recovery | |

| Malik et al[12], 2010 | United States | F | 22 | Diarrhea, Abdominal Pain | CD | None | NA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA, Mycophenolate Mofetil | Y | Recovery | |

| Lamia et al[13], 2012 | Tunisia | M | 4 | Hematuria, Diarrhea, Hepatomegaly, Splenomegaly | NSIC | None | ANA, pANCA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA, 6-MP | Y | Recovery | |

| Lee et al[14], 2005 | Malaysia | F | 5 | Jaundice, Itching, Steatorrhea | N | None | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, UDCA | N | Recovery | |

| Santos et al[15], 2012 | Colombia | M | 36 | Jaundice, Hematemesis, Abdominal Pain, Hepatomegaly, Ascites | N | Cirrhosis, Encephalopathy, Esophageal Varices | ANA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | Liver transplantation |

| Santos et al[15], 2012 | Colombia | F | 35 | Headache, Jaundice, Fatigue | UC | Esophageal Varices | ANA, pANCA, SMA | NA | Steroids, UDCA, MSM | Y | Recovery | |

| Santos et al[15], 2012 | Colombia | F | 45 | Jaundice, Choluria, Acholia, Hepatomegaly | NSIC | Hypothyroidism | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | N | Recovery | |

| Saltik-Temizel et al[16], 2004 | Turkey | M | 11 | Jaundice, Itching, Abdominal Pain, Hepatomegaly, Splenomegaly, Fecal Occult Blood | UC | None | pANCA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA, MSM | Y | Recovery | |

| Gopal et al[17], 1999; Nagral et al[18], 1999 | India | F | 14 | Jaundice, Hepatomegaly, Splenomegaly, Ascites | N | Cirrhosis, Esophageal Varices | ANA | NA | Steroids, D-penicillamine | Y | Recovery | Liver transplantation |

| Lüth et al[19], 2009 | Germany | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Farid et al[20], 2015 | Bahrain | F | 11 | Jaundice, Nausea, Vomit, Abdominal Pain | UC | Cirrhosis | NA | NA | Steroids, AZA | Y | Death | Liver transplantation |

| Floreani et al[21], 2005 | Italy | F | 26 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Floreani et al[21], 2005 | Italy | M | 19 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Floreani et al[21], 2005 | Italy | M | 32 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Floreani et al[21], 2005 | Italy | M | 27 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Floreani et al[21], 2005 | Italy | F | 15 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Liver transplantation |

| Floreani et al[21], 2005 | Italy | F | 15 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Floreani et al[21], 2005 | Italy | F | 16 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Gohlke et al[22], 1996; Zenouzi et al[23], 2014 | Germany | M | 19 | NA | N | Esophageal Varices | ANA, pANCA, SMA | A1, A32, B8, Cw3, Cw7, DR3, DR4 | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | |

| Gohlke et al[22], 1996; Zenouzi et al[23], 2014 | Germany | M | 28 | NA | UC | Esophageal Varices | ANA, pANCA | A1, A32, B7, B8, Cw7, DR3, DR4, DR52, DR53, DQ2, DQ3 | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | |

| Gohlke et al[22], 1996; Zenouzi et al[23], 2014 | Germany | M | 18 | NA | N | Cirrhosis, Esophageal Varices | ANA, pANCA, SMA | A1, A25, B8, DR3 | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | Liver transplantation |

| Abdo et al[24], 2002 | Canada | M | 15 | Jaundice, Fatigue | UC | None | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA | Y | Recovery | |

| Abdo et al[24], 2002 | Canada | M | 51 | Abdominal Pain, Weight Loss, Fatigue | N | None | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | |

| Abdo et al[24], 2002 | Canada | M | 54 | Abdominal Pain, Fatigue, Splenomegaly | UC | Cirrhosis, Alcohol-induced Pancreatitis | NA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA, MSM | Y | Recovery | |

| Abdo et al[24], 2002 | Canada | F | 25 | Jaundice, Itching, Abdominal Pain, Fatigue, Hepatomegaly | N | None | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | |

| Abdo et al[24], 2002 | Canada | F | 23 | Fatigue | UC | None | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA, MSM | Y | Recovery | |

| Abdo et al[24], 2002 | Canada | M | 20 | Jaundice, Abdominal Pain, Weight Loss, Hepatomegaly, Splenomegaly | N | Cirrhosis | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | Liver transplantation |

| van Buuren et al[25], 2000 | Netherlands | M | 7 | NA | UC | None | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA | NA | Recovery | |

| van Buuren et al[25], 2000 | Netherlands | M | 14 | NA | CD | None | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA | NA | Recovery | |

| van Buuren et al[25], 2000 | Netherlands | F | 21 | NA | UC | None | ANA, pANCA | NA | Steroids, AZA | NA | Recovery | |

| van Buuren et al[25], 2000 | Netherlands | F | 22 | NA | CD | None | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA | Y | Recovery | Liver transplantation |

| van Buuren et al[25], 2000 | Netherlands | M | 20 | NA | UC | None | SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | NA | Recovery | |

| van Buuren et al[25], 2000 | Netherlands | M | 23 | NA | UC | Cirrhosis, Esophageal Varices | ANA, pANCA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | NA | Recovery | |

| van Buuren et al[25], 2000 | Netherlands | M | 37 | NA | N | None | ANA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | NA | Recovery | |

| van Buuren et al[25], 2000 | Netherlands | M | 54 | NA | CD | None | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | Liver transplantation |

| van Buuren et al[25], 2000 | Netherlands | F | 44 | Jaundice | UC | Hepatic Insufficiency | pANCA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | Liver transplantation |

| Li et al[26], 2017 | China | M | 52 | Jaundice, Itching | N | Rheumatoid Arthritis | NA | NA | Steroids | N | Recovery | |

| Gharibpoor et al[27], 2017 | Iran | M | 26 | Jaundice, Itching, Choluria, Acholia, Abdominal Pain, Weight Loss, Hepatomegaly | N | None | ANA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | N | Recovery | |

| Sander et al[28], 2007 | Germany | M | 24 | CD | None | ANA, SMA | B8, DR4 | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | ||

| Smolka et al[29], 2016 | Czech Republic | M | 16 | Jaundice | N | None | ANA, pANCA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Smolka et al[29], 2016 | Czech Republic | M | 17 | Diarrhea, Abdominal Pain | UC | None | pANCA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Smolka et al[29], 2016 | Czech Republic | F | 15 | Fatigue | N | None | pANCA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Smolka et al[29], 2016 | Czech Republic | M | 14 | UC | None | NA, pANCA, SMA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Smolka et al[29], 2016 | Czech Republic | F | 16 | CD | None | pANCA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Smolka et al[29], 2016 | Czech Republic | F | 10 | Fever, Weight Loss, Fatigue | NSIC | None | LKM1, pANCA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Smolka et al[29], 2016 | Czech Republic | M | 12 | Abdominal Pain | UC | None | pANCA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Smolka et al[29], 2016 | Czech Republic | F | 9 | Melena, Fatigue | UC | None | ANA, pANCA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Smolka et al[29], 2016 | Czech Republic | M | 3 | Diarrhea, Abdominal Pain | UC | None | ANA, pANCA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Smolka et al[29], 2016 | Czech Republic | F | 9 | N | None | ANA, pANCA, SMA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Smolka et al[29], 2016 | Czech Republic | F | 15 | Itching, Diarrhea, Abdominal Pain | CD | None | ANA, pANCA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Griga et al[30], 2000 | United Kingdom | F | 24 | Diarrhea | CD | None | ANA, pANCA | NA | Steroids, MSM, UDCA | N | Recovery | |

| Griga et al[30], 2000 | United Kingdom | M | 28 | Jaundice, Itching | N | None | ANA, pANCA | B8, DR4 | Steroids, UDCA | N | Recovery | |

| Warling et al[31], 2014 | Belgium | M | 29 | Jaundice, Fatigue | UC | Membranous Glomerulonephritis | pANCA | DR3 | Steroids, AZA, UDCA, MSM, 6-MP | Y | Recovery | |

| Hyslop et al[32], 2010 | United States | NA | 40 | NA | UC | None | ANA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hyslop et al[32], 2010 | United States | NA | 24 | NA | UC | None | ANA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hyslop et al[32], 2010 | United States | NA | 53 | NA | CD | Cirrhosis | ANA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hyslop et al[32], 2010 | United States | NA | 37 | NA | UC | None | ANA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hyslop et al[32], 2010 | United States | NA | 32 | NA | UC | Cirrhosis | ANA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hyslop et al[32], 2010 | United States | NA | 61 | NA | CD | Cirrhosis | ANA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hyslop et al[32], 2010 | United States | NA | 52 | NA | CD | None | ANA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hyslop et al[32], 2010 | United States | NA | 26 | NA | CD | Cirrhosis | ANA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hyslop et al[32], 2010 | United States | NA | 33 | NA | UC | None | ANA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hyslop et al[32], 2010 | United States | NA | 44 | NA | UC | Cirrhosis | ANA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Fukuda et al[33], 2012 | Japan | M | 72 | Ascites | N | Cirrhosis, Hepatocellular Carcinoma | ANA, AMA | DRB1*0405, DRB1*0901 | Steroids, UDCA | Y | Death | |

| Hatzis et al[34], 2001 | Greece | F | 46 | Fever, Arthralgia, Fatigue, Splenomegaly | N | Nephrectomy for Reflux Nephropathy | ANA, pANCA, SMA | A3, A11, B16, B35, Cw4, DR13, DR14, DR52, DQ6 | Steroids, AZA, UDCA, Antibiotics | N | Recovery | |

| Thakker et al[35], 2010 | India | F | 9 | Fever, Jaundice, Itching, Arthralgia, Fatigue, Hepatomegaly, Splenomegaly | N | None | ANA | NA | Steroids, UDCA | N | Recovery | |

| Koskinas et al[36], 1999 | Greece | M | 18 | Fever, Jaundice, Hematochezia, Fatigue, Hepatomegaly, Splenomegaly, Ascites | UC | Pyoderma Gangrenosum | NA | A2, A32, B7, B21, B49, Bw4, Bw6, DR6, DR10, DR13 | Steroids, AZA, UDCA, MSM, Antibiotics | Y | Recovery | |

| Lucas et al[37], 2007 | United States | M | 18 | Fecal incontinence, Abdominal Pain | UC | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Protzer et al[38], 1996 | Switzerland | M | 22 | Jaundice, Nausea, Diarrhea, Abdominal Pain, Fatigue | UC | PIGCH | SMA | A1, A2, B8, B44, Cw5, Cw7, DR3, DR52, DQ2 | Steroids, UDCA | Y | Recovery | |

| Protzer et al[38], 1996 | Switzerland | F | 32 | N | PIGCH | pANCA | A2, A28, B55, B67, Cw3, DR4, DR11, DQ2, DQ3 | Steroids, AZA | Y | Recovery | ||

| Protzer et al[38], 1996 | Switzerland | M | 28 | N | Cirrhosis, PIGCH | ANA | A1, B8, DR3 | Steroids, AZA | Y | Death | ||

| Protzer et al[38], 1996 | Switzerland | M | 26 | N | PIGCH | ANA | A1, B8, DR3 | Steroids, UDCA | Y | Recovery | ||

| Hong-Curtis et al[39], 2004 | United States | F | 34 | Jaundice, Itching, Fatigue | UC | Anemia | ANA | NA | Steroids, UDCA, Antibiotics | Y | Recovery | |

| Simão et al[40], 2012 | Portugal | M | 15 | Itching | N | None | ANA, AMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | Y | Recovery | |

| Larsen et al[41], 2012 | Denmark | M | 10 | Vomiting, Diarrhea, Abdominal Pain, Weight Loss | CD | None | pANCA, SMA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | N | Recovery | |

| Guerra et al[42], 2016 | Peru | F | 22 | Jaundice, Choluria, Fatigue, Splenomegaly, Ascites | N | Cirrhosis, Esophageal Varices | ANA | A2, A11, B35, B60, DR9, DR13 | Steroids, UDCA | Y | Recovery | Liver transplantation |

| Ng et al[43], 2011 | Australia | F | 33 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | UDCA | NA | NA | |

| Igarashi et al[44], 2017 | Japan | F | 19 | N | None | ANA | NA | Steroids, UDCA | Y | Recovery | ||

| Igarashi et al[44], 2017 | Japan | M | 61 | N | Renal Cell Carcinoma | NA | NA | Steroids, UDCA | Y | Recovery | ||

| Gargouri et al[45], 2013 | Tunisia | M | 10 | Jaundice, Abdominal Pain, Fatigue, Hepatomegaly, Splenomegaly | N | Esophageal Varices | pANCA | NA | Steroids, AZA, UDCA | N | Recovery | |

| Patrico et al[46], 2013 | Italy | F | 7 | Fever, Acholia, Hepatomegaly | N | None | LKM1 | NA | Steroids, AZ | Y | Recovery |

M: Male; F: Female; NA: Not available; ND: Not determined, IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; CD: Crohn’s Disease, UC: Ulcerative Colitis, NSIC: Non Specific Inflammatory Colitis, OS: Overlap syndrome, PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis, AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis, PIGCH: Post-infantile Giant Cell Hepatitis, MSM: Mesalamine, SFZ: Sulfasalazine, UDCA: Ursodeoxycholic Acid, AZA: Azathioprine, 6-MP: 6-Mercaptopurine, IFX: Infliximab, ADM: Adalimumab, LKM1: Liver kidney microsome type 1 antibody, AMA: Anti-mitochondrial antibodies, ANA: Antinuclear antibody, SMA: Smooth muscle antibodies, pANCA: Perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies.

The medications administered are described in 63 (58.33%) patients. Of these, 62 (98.41%) patients received steroids; 49 (77.77%) patients received thiopurines (48 on azathioprine and 1 on 6-mercaptopurine) and 7 (11.11%) patients received aminosalicylates (mesalamine); 47 (74.60%) patients received ursodeoxycholic acid. Other medications administered were antibiotics (4.76%), mycophenolate mofetil (3.17%), and D-penicillamine (1.58%). Medication use in 45 (41.66%) of 109 patients was unavailable.

DISCUSSION

This is a systematic review of clinical presentations and outcomes of patients with PSC/AIH OS. The findings are described in Tables 1 and 2. In this discussion, unavailable data were not considered[47].

PSC/AIH OS is not an uncommon presentation in the clinic, and occurs in 18% of patients with AIH[48,49]. As previously stated, PSC/AIH OS is characterized by the presence of histologic, serologic, and laboratory features of AIH, with biliary stricture compatible with PSC[50,51]. As described in other studies, it affects predominantly children, adolescents, and young male adults[25,50] which is consistent with our results where the mean age was 25.52 years (22.52-28.51) and the prevalence was higher in men (56.09%). Furthermore, PSC can be divided into large and small ducts, with reports of the latter being rare in the literature[52], which is consistent with our findings, where the prevalence of patients presenting with small-duct PSC was 3.70%.

With regard to the clinical features, most patients present with signs and symptoms of biliary duct involvement[53]. These were common findings in the cases reviewed here and included jaundice, choluria, acholia, and abdominal pain. Moreover, liver function tests in our patient, such as gamma-glutamyltransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase were elevated and were between the confidence interval (95%) described in Table 1 and those in the literature[54]. However, laboratory tests such as total and direct bilirubin were higher levels in the case reported here (12.3 mg/dL and 10 mg/dL, respectively) than in the studies reviewed and described in Table 1. Other tests for viral hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr, and herpes simplex were negative. Tests for other diseases were performed as part of the diagnostic workup and all were negative. Moreover, the antinuclear antibody was positive in our patient and in the majority of patients described.

Our findings demonstrated an elevated prevalence of IBD with PCS/AIH OS (57.14%), which has been shown in other studies[55,56]. It was reported that UC is found in to up to 16% of patients with AIH[57], whereas, in our study, this association was increased (38.09%), followed by the association with Crohn’s disease (15.47%) and non-specific IBD (3.57%).

Treatment was started and a liver biopsy was performed, which confirmed PSC/AIH OS. The majority of patients in the systematic review were treated with steroids (98.41%) associated with other medications, such as azathioprine or ursodeoxycholic acid. Clinical improvement was satisfactory, leading to recovery in 104 (96.30%) patients. The only patient who received D-penicillamine underwent liver transplantation and later recovered. Our patient started with steroids, azathioprine and mesalamine, with a good clinical response, similar to reports in the literature[58].

The main limitations of our study are the small number of available cases of PSC/AIH OS (n = 109) associated with the lack of available data in many of the cases reviewed. As a result, some of the variables described in Table 1 included a small number of patients and, therefore, were statistically insignificant. Moreover, some studies were excluded as individual patient data were NA; thus limiting, even more, the number of cases to be reviewed. Despite these limitations, most of the variables shown in Table 1 were between the confidence interval and this systematic review was able to reinforce some of the literature findings and raise doubts regarding other findings.

In conclusion, PCS/AIH OS has a good response to treatment with steroids, azathioprine and ursodeoxycholic acid and is associated with IBD. It should be suspected in patients with recurrent jaundice, pruritus and abdominal pain or other signals of biliary impairment with suggestive laboratory and imaging tests, especially if associated with IBD. In more severe cases, liver transplantation can be performed[5,6,15,17,20-22,24,25,42] with comparable graft and patient survival, as transplantation-free survival in patients with PSC/AIH OS is worse than that in patients with AIH only[58].

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a progressive disorder that causes inflammation and scarring of bile ducts, leading to fibrosis, strictures and dilatation of the biliary tree. The etiology and pathogenesis of PSC are currently unknown, although PSC is highly associated with the presence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic inflammatory liver disease with specific laboratory and histological findings. It is characterized by elevated serum aminotransferases, increased total IgG and positive autoantibodies, whereas liver biopsy may show interface hepatitis and portal mononuclear cell infiltrate. In some cases, patients may present with variant forms of AIH, in which there is an overlap of AIH and another autoimmune liver disease, such as PSC. Therefore, PSC/AIH overlap syndrome (OS) is a rare disorder characterized by the concomitant occurrence of the biochemical and histological features of AIH and the cholangiography abnormalities found in PSC.

Research motivation

Few cases of PSC/AIH OS have been reported in the literature and many questions are unanswered. Thus, the motivation for this systematic review was to clarify questions regarding the epidemiology, clinical presentation, possible treatments and a better understanding of this syndrome.

Research objectives

The authors report the case of a female patient with AIH and PSC OS associated with ulcerative colitis and systematically review the available cases of AIH and PSC overlap syndrome.

Research methods

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations contained in the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis protocols guidelines. Searches for studies were run on the electronic databases Scopus, Web of Science, Medline (PubMed), Biblioteca Regional de Medicina, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, Cochrane Library for Systematic Reviews and Opengray.eu. Languages were restricted to English, Spanish and Portuguese and there was no date of publication restrictions. The inclusion criteria were clinical case reports or case series involving autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis and the exclusion criteria were studies other than case reports or case series and articles that were not related to the topic. Data, such as patients’ clinical presentation and comorbidities, laboratory results, liver biopsy results and medications used were summarized using descriptive analysis – frequency, means and median, using RStudio and the outcome measured was recovery or death.

Research results

Forty-four references were analyzed and a total of 109 patients diagnosed with PSC/AIH OS were included. Of these, 46 (42.59%) were male. Forty-eight (44.44%) patients had IBD. The most common clinical presentation was jaundice, which was present in 31 (28.70%) cases, followed by fatigue and abdominal pain (20.37% and 19.44%, respectively). PSC was identified in small and large ducts (3.70% and 81.48%, respectively). Medications were administered in 63 (58.33%) patients. Of these, 62 (98.41%) patients received steroids; 49 (77.77%) patients received thiopurines (48 on azathioprine and 1 on 6-mercaptopurine) and 7 (11.11%) patients received aminosalicylates (mesalamine); 47 (74.60%) patients received ursodeoxycholic acid. Clinical improvement with these treatments was satisfactory, leading to recovery in 104 (96.30%) patients.

Research conclusions

AIH/PSC OS has a good response to treatment with steroids, azathioprine and ursodeoxycholic acid and is generally associated with IBD. It should be suspected in patients with recurrent jaundice, pruritus and abdominal pain with laboratory and imaging tests suggestive of both hepatocellular and cholestatic diseases, especially when associated with IBD. In more severe cases, liver transplantation can be performed with comparable graft and patient survival, as transplantation-free survival in patients with PSC/AIH OS is worse than that in patients with AIH only.

Research perspectives

From the present study findings, there is no definitive and highly specific clinical presentation of PSC/AIH OS. Therefore, the gastroenterologist should be aware that patients with laboratory data suggestive of both hepatocellular and cholestatic liver injury should undergo liver biopsy in order to achieve an adequate diagnosis, especially if they have a previous diagnosis of IBD. Also, clinical treatment with steroids, azathioprine, and ursodeoxycholic acid seems to be safe and effective and it seems adequate to consider this association in such cases. If medical treatment fails, liver transplantation is also safe and should be considered earlier than with isolated PSC or AIH. The direction of future research should be clinical trials of possible treatments for PSC/AIH OS, as we expect it to become more common, as the prevalence of IBD has been steadily rising in the past decades.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The guidelines of the PRISMA 2009 statement have been adopted.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Federação Brasileira De Gastroenterologia.

Peer-review started: March 21, 2020

First decision: April 8, 2020

Article in press: July 30, 2020

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chen GX, Kaya M, Tang Y S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Vinícius Remus Ballotin, Faculty of Medicine, Universidade de Caxias do Sul (UCS), Caxias do Sul 95070560, Brazil.

Lucas Goldmann Bigarella, Faculty of Medicine, Universidade de Caxias do Sul (UCS), Caxias do Sul 95070560, Brazil.

Floriano Riva, CPM Laboratório de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul 95070561, Brazil.

Georgia Onzi, Clinical Gastroenterology, Universidade de Caxias do Sul (UCS), Caxias do Sul 95070560, Brazil.

Raul Angelo Balbinot, Clinical Gastroenterology, Universidade de Caxias do Sul (UCS), Caxias do Sul 95070560, Brazil.

Silvana Sartori Balbinot, Clinical Gastroenterology, Universidade de Caxias do Sul (UCS), Caxias do Sul 95070560, Brazil.

Jonathan Soldera, Clinical Gastroenterology, Universidade de Caxias do Sul (UCS), Caxias do Sul 95070560, Brazil. jonathansoldera@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Lazaridis KN, LaRusso NF. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1161–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1506330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czaja AJ, Manns MP. Advances in the diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:58–72.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wurbs D, Klein R, Terracciano LM, Berg PA, Bianchi L. A 28-year-old woman with a combined hepatitic/cholestatic syndrome. Hepatology. 1995;22:1598–1605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence SP, Sherman KE, Lawson JM, Goodman ZD. A 39 year old man with chronic hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 1994;14:97–105. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nalepa A, Woźniak M, Cielecka-Kuszyk J, Stefanowicz M, Jankowska I, Dądalski M, Pawłowska J. Acute-on-chronic hepatitis. A case report of autoimmune hepatitis/primary sclerosing cholangitis/ulcerative colitis overlap syndrome in a 15-year-old patient. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2017;3:28–32. doi: 10.5114/ceh.2017.65501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luketic VA, Gomez DA, Sanyal AJ, Shiffman ML. An atypical presentation for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2009–2016. doi: 10.1023/a:1018845829198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mueller T, Bianchi L, Menges M. Autoimmune hepatitis 2 years after the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis: an unusual overlap syndrome in a 17-year-old adolescent. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:232–236. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282e1c648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerrero-Hernández I, Montaño-Loza A, Gallegos-Orozco JF, Weimersheimer-Sandoval M. [Autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis: dependent or independent association?] Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2007;72:240–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takiguchi J, Ohira H, Rai T, Shishido S, Tojo J, Sato Y, Kasukawa R, Watanabe H, Funabashi Y, Kumakawa H. Autoimmune hepatitis overlapping with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Intern Med. 2002;41:696–700. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.41.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNair AN, Moloney M, Portmann BC, Williams R, McFarlane IG. Autoimmune hepatitis overlapping with primary sclerosing cholangitis in five cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:777–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.224_a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Man SC, Schnell CN, Sas V, Buzoianu AD, Gheban D. Autoimmune hepatitis with sclerosing cholangitis in a patient with thiopurine methyltransferase deficiency: case presentation. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2017;58:211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malik TA, Gutierrez AM, McGuire B, Zarzour JG, Mukhtar F, Bloomer J. Autoimmune hepatitis-primary sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome complicated by Crohn's disease. Digestion. 2010;82:24–26. doi: 10.1159/000273735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamia S, Sana K, Rachid J, Hajer A, Leila M, Nabil T, Mongia H. Autoimmune hepatitis-primary sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome complicated by inflammatory bowel disease. Tunis Med. 2012;90:899–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee WS, Saw CB, Sarji SA. Autoimmune hepatitis/primary sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome in a child: diagnostic usefulness of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:225–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santos OM, Muñoz Ortiz E, Pérez C, Restrepo JC. [Autoimmune hepatitis/primary sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome in adults: report of three cases] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;35:254–258. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saltik-Temizel IN. Autoimmune hepatitis/sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome with inflammatory bowel disease in a boy: role ofMR cholangiopancreatography in the diagnosis. Eur J Radiol Extra. 2004;50:45–47. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gopal S, Nagral A, Mehta S. Autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis: an overlap syndrome in a child. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1999;18:31–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagral A, Gopal S, Mehta S. Autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis in a child. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1999;18:91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lüth S, Kanzler S, Frenzel C, Kasper HU, Dienes HP, Schramm C, Galle PR, Herkel J, Lohse AW. Characteristics and long-term prognosis of the autoimmune hepatitis/primary sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:75–80. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318157c614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farid E, Isa HM, Al Nasef M, Mohamed R, Jamsheer H. Childhood Autoimmune Hepatitis in Bahrain: a Tertiary Center Experience. Iran J Immunol. 2015;12:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Floreani A, Rizzotto ER, Ferrara F, Carderi I, Caroli D, Blasone L, Baldo V. Clinical course and outcome of autoimmune hepatitis/primary sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1516–1522. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gohlke F, Lohse AW, Dienes HP, Löhr H, Märker-Hermann E, Gerken G, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Evidence for an overlap syndrome of autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 1996;24:699–705. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zenouzi R, Lohse AW. Long-term outcome in PSC/AIH "overlap syndrome": does immunosuppression also treat the PSC component? J Hepatol. 2014;61:1189–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdo AA, Bain VG, Kichian K, Lee SS. Evolution of autoimmune hepatitis to primary sclerosing cholangitis: A sequential syndrome. Hepatology. 2002;36:1393–1399. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.37200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Buuren HR, van Hoogstraten HJE, Terkivatan T, Schalm SW, Vleggaar FP. High prevalence of autoimmune hepatitis among patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2000;33:543–548. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Sun L, Brigstock DR, Qi L, Gao R. IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis overlapping with autoimmune hepatitis: Report of a case. Pathol Res Pract. 2017;213:565–569. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gharibpoor A, Mansour-Ghanaei F, Sadeghi M, Gharibpoor F, Joukar F, Mavaddati S. Innumerable Liver Masses in a Patient with Autoimmune Hepatitis and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis Overlap Syndrome. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:131–135. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.901153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sander LE, Koch A, Gartung C, Winograd R, Donner A, Wellmann A, Trautwein C, Geier A. Lessons from a patient with an unusual hepatic overlap syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:635–640. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smolka V, Karaskova E, Tkachyk O, Aiglova K, Ehrmann J, Michalkova K, Konecny M, Volejnikova J. Long-term follow-up of children and adolescents with primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2016;15:412–418. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(16)60088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griga T, Tromm A, Müller KM, May B. Overlap syndrome between autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis in two cases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:559–564. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012050-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warling O, Bovy C, Coïmbra C, Noterdaeme T, Delwaide J, Louis E. Overlap syndrome consisting of PSC-AIH with concomitant presence of a membranous glomerulonephritis and ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4811–4816. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hyslop WB, Kierans AS, Leonardou P, Fritchie K, Darling J, Elazazzi M, Semelka RC. Overlap syndrome of autoimmune chronic liver diseases: MRI findings. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31:383–389. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuda K, Kogita S, Tsuchimoto Y, Sawai Y, Igura T, Ohama H, Makino Y, Matsumoto Y, Nakahara M, Zushi S, Imai Y. Overlap syndrome of autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis complicated with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2012;5:183–188. doi: 10.1007/s12328-012-0294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hatzis GS, Vassiliou VA, Delladetsima JK. Overlap syndrome of primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:203–206. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200102000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thakker A, Karande S. Overlap syndrome: autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:1063–1065. doi: 10.1007/s13312-010-0164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koskinas J, Raptis I, Manika Z, Hadziyannis S. Overlapping syndrome of autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis associated with pyoderma gangrenosum and ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1421–1424. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199912000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lucas RG, Jr, Lee EY. Overlapping syndrome of autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis associated with ulcerative colitis. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:844. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0480-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Protzer U, Dienes HP, Bianchi L, Lohse AW, Helmreich-Becker I, Gerken G, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Post-infantile giant cell hepatitis in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis. Liver. 1996;16:274–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1996.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong-Curtis J, Yeh MM, Jain D, Lee JH. Rapid progression of autoimmune hepatitis in the background of primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:906–909. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200411000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simão TS. Síndrome de Overlap entre colangite esclerosante primária e hepatite auto -imune – um caso com apresentação sequencial ao longo dos anos. Nascer e Crescer. 2012:102–106. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larsen EP, Bayat A, Vyberg M. Small duct autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis and Crohn colitis in a 10-year-old child. A case report and review of the literature. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:100. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guerra Montero L, Ortega Alvarez F, Marquez Teves M, Asato Higa C, Sumire Umeres J. [Syndrome overlap: autoimmune hepatitis and autoimmune cholangitis] Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2016;36:77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ng S, Janjua M, Kontorinis N, Doyle A, Kong J, Macquillan G, Adams L, Jeffrey G, Garas G, Cheng W. Treatment and outcomes of patients with autoimmune overlap syndromes. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Australia) 2017;32:100–1. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Igarashi G, Endo T, Mikami K, Sawada N, Satake R, Ohta R, Sakamoto J, Yoshimura T, Kurose A, Kijima H, Fukuda S. Two Cases of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis Overlapping with Autoimmune Hepatitis in Adults. Intern Med. 2017;56:509–515. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.56.7633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gargouri L, Mnif L, Safi F, Turki F, Majdoub I, Maalej B, Bahri I, Mnif H, Boudawara T, Tahri N, Mahfoudh A. Type 2 autoimmune hepatitis overlapping with primary sclerosing cholangitis in a 10-year-old boy. Arch Pediatr. 2013;20:1325–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pratico AD, Salafia S, Barone P, La Rosa M, Leonardi S. Type II Autoimmune Hepatitis and Small Duct Sclerosing Cholangitis in a Seven Years Old Child: An Overlap Syndrome? Hepat Mon. 2013;13:e14452. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.14452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Portilho DR, Caixêta NG. Overlap syndrome: A case of ulcerative colitis in a patient with autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis and diabetes mellitus. Revista da AMRIGS. 2019;63:337–339. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beuers U, Rust C. Overlap syndromes. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:311–320. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdalian R, Dhar P, Jhaveri K, Haider M, Guindi M, Heathcote EJ. Prevalence of sclerosing cholangitis in adults with autoimmune hepatitis: evaluating the role of routine magnetic resonance imaging. Hepatology. 2008;47:949–957. doi: 10.1002/hep.22073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rust C, Beuers U. Overlap syndromes among autoimmune liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3368–3373. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Czaja AJ. Diagnosis and management of the overlap syndromes of autoimmune hepatitis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:417–423. doi: 10.1155/2013/198070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaplan GG, Laupland KB, Butzner D, Urbanski SJ, Lee SS. The burden of large and small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis in adults and children: a population-based analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1042–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Czaja AJ. The variant forms of autoimmune hepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:588–598. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-7-199610010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hunter M, Loughrey MB, Gray M, Ellis P, McDougall N, Callender M. Evaluating distinctive features for early diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome in adults with autoimmune hepatitis. Ulster Med J. 2011;80:15–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woodward J, Neuberger J. Autoimmune overlap syndromes. Hepatology. 2001;33:994–1002. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.23316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al-Chalabi T, Portmann BC, Bernal W, McFarlane IG, Heneghan MA. Autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndromes: an evaluation of treatment response, long-term outcome and survival. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:209–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perdigoto R, Carpenter HA, Czaja AJ. Frequency and significance of chronic ulcerative colitis in severe corticosteroid-treated autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1992;14:325–331. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(92)90178-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Czaja AJ. Frequency and nature of the variant syndromes of autoimmune liver disease. Hepatology. 1998;28:360–365. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]