Abstract

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, African-American mothers were three times as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes compared to white mothers. The impact of the pandemic among African-Americans could further worsen the racial disparities in maternal mortality (MM) and severe maternal morbidity (SMM). This study aimed to create a theoretical framework delineating the contributors to an expected rise in maternal mortality (MM) and severe maternal morbidity (SMM) among African-Americans in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic due to preliminary studies suggesting heightened vulnerability of African-Americans to the virus as well as its adverse health effects. Rapid searches were conducted in PubMed and Google to identify published articles on the health determinants of MM and SMM that have been or likely to be disproportionately affected by the pandemic in African-Americans. We identified socioeconomic and health trends determinants that may contribute to future adverse maternal health outcomes. There is a need to intensify advocacy, implement culturally acceptable programs, and formulate policies to address social determinants of health.

Keywords: COVID-19, Maternal mortality, Severe maternal morbidity, African-Americans

1. Introduction

Globally, millions of people have been infected with the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). In the United States (US), African-American people are being hospitalized and dying in disproportionately greater numbers due to the COVID-19 pandemic. African-Americans comprise less than 13% of the population but account for 33.1% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients.1 This unequal burden of the disease could partially be explained by the higher prevalence of underlying chronic medical conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity among African-Americans. Prior to the pandemic, African-American mothers were three times as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes compared to white mothers.2 The current burden of both chronic diseases and COVID-19 pandemic among African-Americans could further worsen the racial disparities in maternal mortality (MM) and severe maternal morbidity (SMM). The purpose of this paper was to create a theoretical framework delineating the contributors to an expected rise in MM and SMM among African-Americans in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic due to preliminary studies suggesting heightened vulnerability of African-Americans to the virus as well as its adverse health effects.1,3 We also present policy recommendations to address the anticipated widening of the existing maternal health disparity.

2. Methods

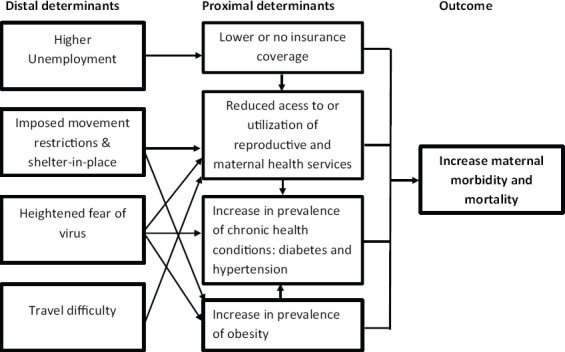

Rapid searches were conducted in PubMed and Google to identify published articles on the select health determinants of MM and SMM that have been or likely to be disproportionately affected by the pandemic in African-Americans. The following keywords were used separately and in combination: “maternal mortality”, “severe maternal morbidity”, “race/ethnicity”, “black or African-American”, “determinants”, “disparity” and “COVID-19”. Since this was a rapid mini-review, and due to the fast turnover of COVID-19 publications, it would be misleading and inappropriate to provide retrieval numbers. The theoretical framework for this study was based on a population health determinants model.4 The determinants of population health are commonly classified as either proximal or distal. Proximal factors act directly to cause the outcome, while distal determinants are further back in the causal chain and indirectly influence health by acting on the more proximal factors, their interrelated mechanisms, and distributions.4,5 The identified determinants from our searches were classified as proximal or distal determinants, and a conceptual framework to explain the expected rise in MM and SMM in African-Americans due to the pandemic was created.

3. Results

Six articles were synthesized in this brief review. The identified proximal determinants are lower insurance coverage, reduced access to or utilization of reproductive and maternal health services, and an increase in the prevalence of chronic health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. The distal determinants include higher unemployment, heightened fear of the virus, travel difficulty, and shelter-in-place restrictions. Figure 1 describes the proposed theoretical framework for a projected increase in MM and SMM in African American women as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. It also highlights the link between the identified proximal and distal determinants and the outcomes.

Figure 1.

A theoretical framework to explain a projected increase in maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity in US African American women in the era of COVID-19 Pandemic

The economic crisis, due to the ongoing pandemic, has led to a higher unemployment rate in African-Americans. From April to May 2020, the unemployment rate rose from 16.4 to 16.5% in African-American women but decreased from 15.0% to 13.1% in white women.6 Among African-American women, this may result in differential loss of insurance coverage and the inability to pay for health services. Lack of health insurance or insufficient healthcare access correlates negatively with the use and quality of maternal health services and potentially better maternal health outcomes.7

Compounding reduced health care access is the government-imposed movement and shelter-in-place restrictions, heightened fear of the virus, and travel difficulty due to reliance on public transport, which all affects African-Americans disproportionately. About 19% of African-Americans compared to only 4.6% of whites live in homes in which no one owns a car.8 The highlighted distal determinants may lead to underutilization of reproductive and maternal health services, resulting in reduced preconception and prenatal visits and missed postpartum visits. Abortion and contraceptive services to prevent unwanted or high-risk pregnancies may also be underutilized. Inadequate prenatal care is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.7 Additionally, preconception and postpartum care are essential for monitoring the health of women with chronic illness, linking vulnerable women with the health system and reducing SMM and MM.9

A recent study estimated that 31%, 17%, and 4.9% of the attributable increase in maternal mortality were due to the proportion of obese women of childbearing age, the proportion of births to women with diabetes, and births to women attending fewer than ten prenatal visits respectively. 7 These determinants could be affected negatively during the pandemic. For instance, the prevalence of obesity might increase because of shelter-at-home, while diabetes may be undiagnosed or untreated because of insufficient healthcare access. Further, elevated BMI also increases the risk of chronic health conditions, including diabetes mellitus and hypertension.7 African-American women already have a higher prevalence of obesity and may be disproportionately affected during this crisis. As evident from previous research, small changes in body weight in relatively short time periods can become permanent and lead to substantial weight gain over time. 10 Considering the surge of COVID-19 cases in the US due to the reopening of states, the stay-at-home order could be extended and may last several months. As a result, extended home confinement due to COVID-19 could result in significant body weight gain, with women with overweight/obesity being at the greatest risk for permanent change.11

4. Discussion and Global Health Implications

In the coming months, the US may expect to see a substantial increase in pregnancy and childbirth-related complications and deaths among African-American women. The significant changes in socioeconomic factors and health trends because of COVID-19 may play an important role. African American women constitute a population with social vulnerabilities, and to mitigate the inevitable rise in maternal mortality and morbidity, it is necessary to target the proximal and distal risk factors noted in this study.

Given the historical context of systemic racism among African-Americans, there is a need to intensify advocacy, implement culturally acceptable intervention programs, and formulate policies to address social determinants of health and make equitable social justice a reality. Globally, to sustain the gains in maternal health achieved in the past decades, country-level assessments of the pandemic-related altered risk factors that may affect maternal health, particularly among high-risk populations, are warranted and appropriate interventions implemented.

Key Messages.

The significant changes in socioeconomic factors and health trends because of the COVID-19 pandemic may contribute to an expected rise in maternal mortality (MM) and severe maternal morbidity (SMM) among African-Americans.

The proximal contributors to this anticipated surge in adverse maternal health outcomes among African-Americans are lower insurance coverage, reduced access to or utilization of reproductive and maternal health services, and an increase in the prevalence of chronic health conditions. The distal determinants include higher unemployment, heightened fear of the virus, travel difficulty, and shelter-in-place restrictions.

There is a need to intensify advocacy, implement culturally acceptable intervention programs, and formulate policies to address social determinants of health and make social justice a reality.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure: None declared.

Funding/Support: The publication of this article was partially supported by the Global Health and Education Projects, Inc. (GHEP) through the Emerging Scholars Grant Program (ESGP). The information, contents, and conclusions are those of the authors’ and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by ESGP or GHEP.

Ethics Approval: This study was based on existign literature.

References

- 1.Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 - COVID-NET, 14 states, March 1-30 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):458–464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgess APH, Dongarwar D, Spigel Z, Salihu HM, Moaddab A, Clark SL, Fox K. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States 2003-2016:Age, race, and place of death. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(5):489.e1–489.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SJ, Bostwick W. Social Vulnerability and Racial Inequality in COVID-19 Deaths in Chicago. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47(4):509–513. doi: 10.1177/1090198120929677. doi:10.1177/1090198120929677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arah OA, Westert GP, Delnoij DM, Klazinga NS. Health system outcomes and determinants amenable to public health in industrialized countries:A pooled, cross-sectional time series analysis. BMC Public Health. 2005;5 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-81. 81-2458-5-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2002:Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. [Accessed June 25 2020]. https://www.who.int/whr/2002/en/whr02_en.pdf?ua=1 .

- 6.U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics. Table A-2. Employment status of the civilian population by race, sex, and age. 2020. Jun 05, [Accessed June 25 2020]. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t02.htm .

- 7.Nelson DB, Moniz MH, Davis MM. Population-level factors associated with maternal mortality in the united states 1997-2012. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5935-2. 1007-018-5935-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berube A, Raphael S. Paper presented at:Berkeley Symposium on Real Estate, Catastrophic Risk, and Public Policy;March 22-23. Berkeley, CA: 2006. [Accessed June 25 2020]. Socioeconomic differences in household automobile ownership rates:implications for evacuation policy. https://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2006/03/23_carownership.shtml . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howell EA. Reducing disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61(2):387–399. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoeller DA. The effect of holiday weight gain on body weight. Physiol Behav. 2014;134:66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhutani S, Cooper JA. COVID-19 related home confinement in adults:Weight gain risks and opportunities. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.22904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]