Summary

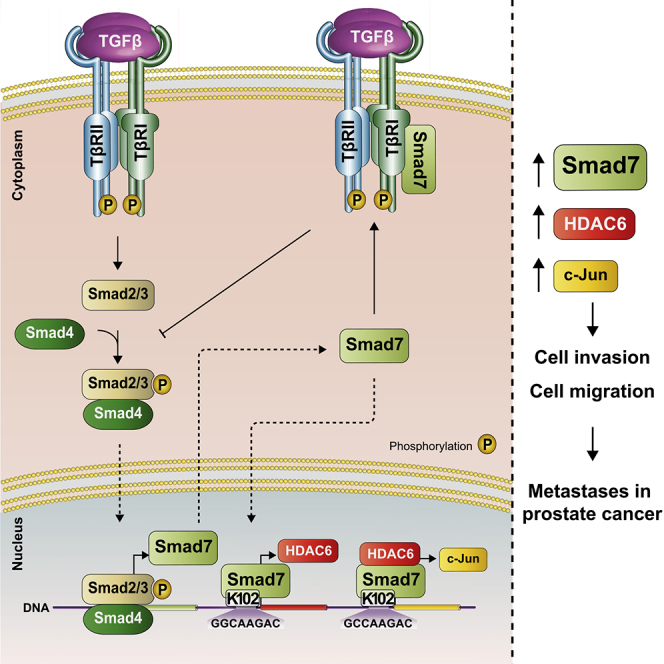

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) enhances migration and invasion of cancer cells, causing life-threatening metastasis. Smad7 expression is induced by TGF-β to control TGF-β signaling in a negative feedback manner. Here we report an additional function of Smad7, i.e., to enhance TGF-β induction of c-Jun and HDAC6 via binding to their regulatory regions, promoting migration and invasion of prostate cancer cells. Lysine 102 in Smad7 is crucial for binding to specific consensus sites in c-Jun and HDAC6, even when endogenous Smad2, 3, and 4 were silenced by siRNA. A correlation between the mRNA expression of Smad7 and HDAC6, Smad7 and c-Jun, and c-Jun and HDAC6 was found in public databases from analyses of prostate cancer tissues. High expression of Smad7, HDAC6, and c-Jun correlated with poor prognosis for patients with prostate cancer. The knowledge that Smad7 can activate transcription of proinvasive genes leading to prostate cancer progression provides clinically relevant information.

Subject Areas: Molecular Biology, Cell Biology, Cancer

Graphical Abstract

For a Figure360 author presentation of this figure, see https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101470.

Highlights

-

•

TGF-β promotes prostate cancer cell migration and invasion, via Smad7

-

•

Lysine 102 in Smad7 binds to DNA in regulatory regions of HDAC6 and c-Jun

-

•

Smad7 regulates expression of HDAC6 and c-Jun in prostate cancer in response to TGF-β

-

•

High levels of Smad7, c-Jun, and HDAC6 are found in aggressive prostate cancer tissues

Molecular Biology; Cell Biology; Cancer

Introduction

TGF-β is a pleiotropic cytokine that regulates cellular responses, such as proliferation and migration, during embryonal development and tissue homeostasis; in addition, TGF-β signaling is perturbed in diseases, including tumorigenesis (Bierie and Moses, 2006; Derynck and Akhurst, 2007; Heldin and Moustakas, 2016; Massague, 2012). TGF-β signals through type I (TβRI) and type II (TβRII) serine/threonine kinase receptors leading to phosphorylation of R-Smads (Smad2 and Smad3), which form complexes with Smad4 that are translocated to the nucleus to regulate transcription of genes. Smad7, an inhibitory (I)-Smad, has been shown to inhibit TGF-β signaling by competing with R-Smads for receptor binding and by recruitment of ubiquitin ligases targeting the receptors for degradation and phosphatases for dephosphorylating and deactivating the receptors (Hanyu et al., 2001; Hayashi et al., 1997; Kwon et al., 2013; Morikawa et al., 2016; Shi and Massague, 2003). In addition, Smad7 binds to the Smad-binding elements (SBEs) of the PAI-1 gene promoter and prevents the binding of R-Smads, thereby inhibiting the induction of PAI-1 by TGF-β (Zhang et al., 2007).

TGF-β also activates non-Smad signaling pathways (Edlund et al., 2003), in which the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) is crucial (Gudey et al., 2014; Hamidi et al., 2017; Mu et al., 2011; Sorrentino et al., 2008; Yamashita et al., 2008). In non-Smad signaling pathways, Smad7 acts as an adaptor bringing together TβRI and TRAF6 with other signaling components (Mu et al., 2012). Moreover, Smad7 also mediates cross talk between TGF-β and certain other signaling pathways; for instance, its expression is induced by γ-interferon/STAT, TNF-α/NF-κB, and epidermal growth factor (Afrakhte et al., 1998; Massague, 2008). The C-terminal region of Smad7 has a conserved Mad homology 2 (MH2) domain but lacks the SXS motif, which in R-Smads is phosphorylated by TβRI. The N-terminal MH1 domain, which is involved in the DNA binding of Smad3 and 4, is only partially conserved in Smad7 (Aragon et al., 2019; Heldin et al., 1997).

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer form and one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths in men (Velonas et al., 2013). In the clinical situation, the diagnosis and prognosis are based on the histopathological grading by using the Gleason score, measurement of the prostate specific antigen (PSA) in blood and clinical staging of prostate cancer (Falzarano et al., 2015; Partin et al., 2002). Despite recent improvements, the existing treatment options for patients with recurrent disease are still limited (Nevo et al., 2019). It is therefore necessary to develop novel methods and biomarkers to predict prognosis and to design novel strategies for treatment of recurrent disease.

TGF-β has opposing effects on normal and malignant prostate cells (Danielpour, 2005). In normal prostate, TGF-β inhibits cell proliferation and regulates cell differentiation of epithelial cells, induces apoptosis, and maintains dormancy of prostate stem cells (Danielpour, 1999; Ricciardelli et al., 2005; Salm et al., 2005). During prostate cancer progression, increased TGF-β expression in stroma and epithelium has been reported (Shariat et al., 2004; Stravodimos et al., 2000), whereas loss of TGF-β receptors in malignant tissues protects them from anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of TGF-β (Kim et al., 1998). Recent studies have demonstrated that disruption of TGF-β signaling by introduction of a dominant negative TβRII in the prostate epithelium of a preclinical adenocarcinoma mouse model leads to accelerated tumor growth (Pu et al., 2017). The increased TGF-β levels in advanced prostate cancer induce stromal expansion, fibroblast-myofibroblast transdifferentiation, angiogenesis, extracellular matrix remodeling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), immune suppression, and metastatic spread (Ahel et al., 2019; Assinder et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2000; Wikstrom et al., 1998). Aberrant TGF-β signaling has been observed in a preclinical prostate cancer model, in which the tumor suppressor PTEN is silenced specifically in the prostate, leading to premalignant alterations of the prostate epithelium. In this model, enhanced activation of the PI3K pathway and increased levels of Smad4 protein were observed, whereas reduced Smad4 expression correlated with metastatic tumor progression, supporting a role of Smad4 acting as a tumor suppressor in prostate cancer (Ding et al., 2011). The report from Ding et al. also identified two genes as being crucial for prostate cancer progression, i.e., cyclin D1 and SPP1 (Ding et al., 2011). Based on this finding it is important to achieve further knowledge about the role and function of aberrant TGF-β signaling in prostate cancer and to identify potential novel treatment strategies for aggressive prostate cancer.

The aim of the present study was to explore the possibility that Smad7 has a role as a transcription factor in the nucleus. We found that Smad7 positively regulates the expression of HDAC6 and c-Jun by binding to their regulatory regions in a TGF-β-dependent manner.

Results

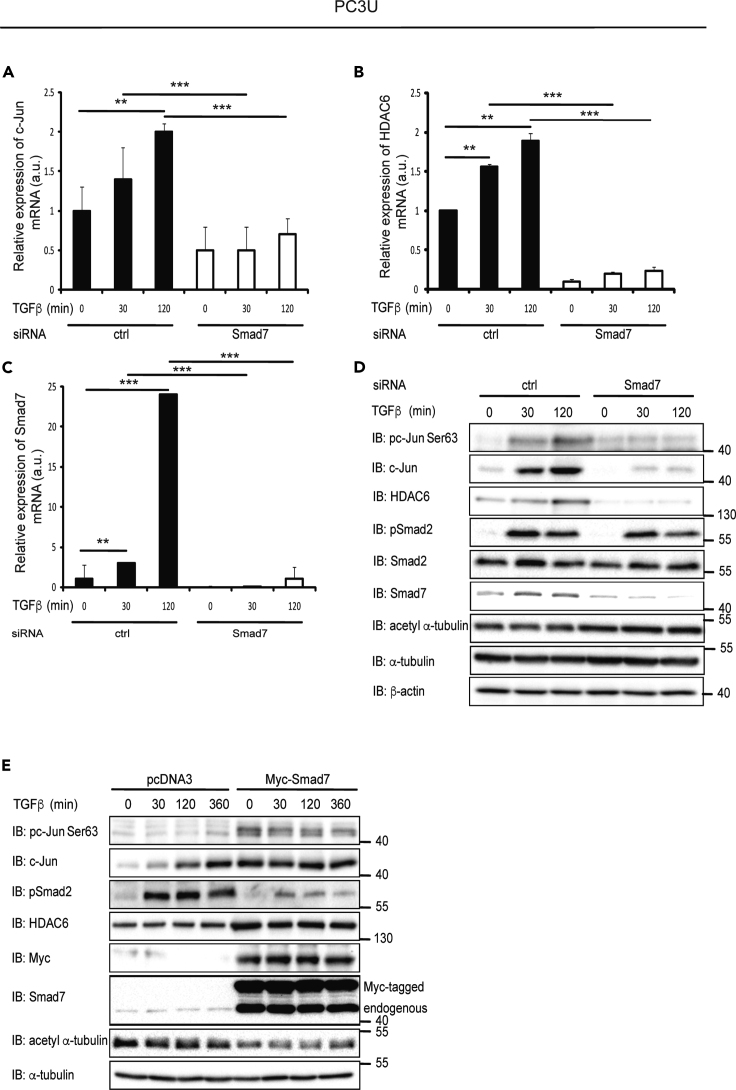

TGF-β-Induced Expression of c-Jun and HDAC6 mRNA and Protein Is Dependent on Smad7

Stimulation of PC3U cells with TGF-β1 led to induction of both c-Jun and HDAC6 (Figure 1). To investigate the importance of Smad7 for HDAC6 and c-Jun expression, Smad7 was knocked down by siRNA in the prostate cancer cell lines PC3U, LNCaP, and DU145; this led to a decreased expression of both c-Jun and HDAC6 mRNA (Figures 1A–1C, S1A, and S2A) and protein (Figures 1D, S1B, and S2B). Overexpression of Myc-Smad7 by transfection in PC3U cells led to an increase in the expression of total c-Jun and HDAC6 (Figure 1E). Our results thus support the notion that Smad7 not only negatively regulates TGF-β signaling (Budi et al., 2017) but also positively regulates the expression of certain genes, including c-Jun and HDAC6.

Figure 1.

TGF-β-Induced Expression of c-Jun and HDAC6 mRNA and Protein Is Dependent on Smad7

(A–C) PC3U cells transfected with control (ctrl) or Smad7 siRNA and stimulated with TGF-β, or not, were lysed and subjected to RT-PCR using c-Jun (A), HDAC6 (B), or Smad7 (C) primers. Graphs are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA was used as the statistical test. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(D) PC3U cells transfected with ctrl or Smad7 siRNA and stimulated or not with TGF-β were lysed and subjected to immunoblotting (IB).

(E) Lysates from PC3U cells transfected with pcDNA3 or Myc-Smad7 plasmids and stimulated with TGF-β, or not, were subjected to immunoblotting.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

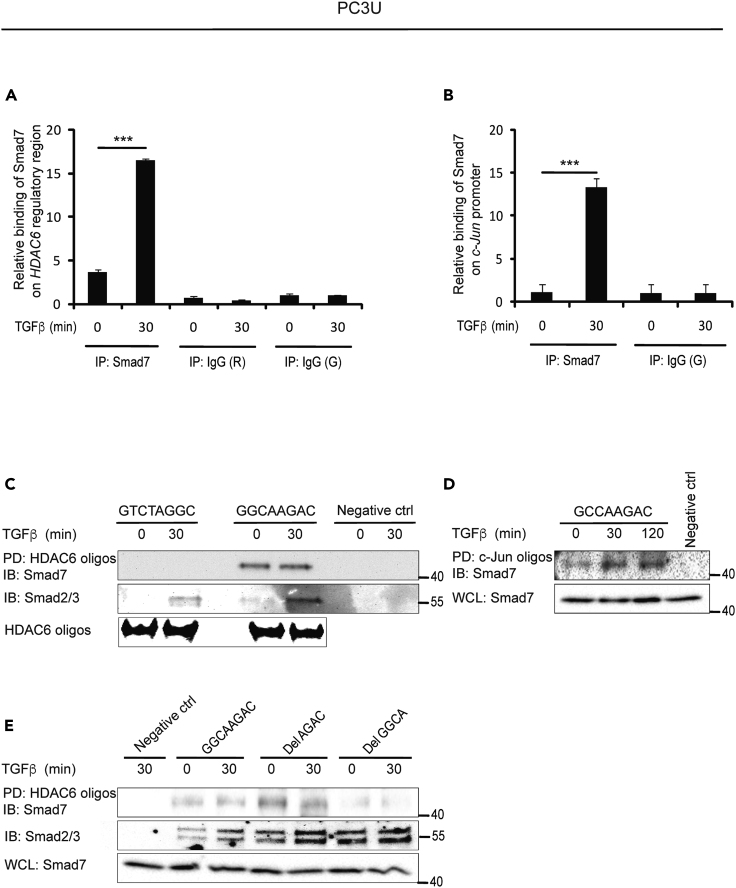

Smad7 Binds to a 5′-GGCA-3′element in HDAC6 and c-Jun Regulatory Regions

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed using different regions of the c-Jun and HDAC6 promoters and regulatory regions to explore the possibility that Smad7 binds directly to sequences in the c-Jun and HDAC6 genes. Regions of about 250 base pairs (bp) in intron 6 of HDAC6 and in the c-Jun promoter were found to be Smad7-binding sites (Figures 2A and 2B). In order to narrow down the potential binding site for Smad7, we analyzed the regulatory regions of the HDAC6 and c-Jun genes for similarities. Two candidate binding sites were found in the regulatory regions of HDAC6 and one in c-Jun. To investigate whether they bound Smad7, DNA affinity precipitation (DNAP) was performed with 52-bp biotinylated oligos containing GGCAAGAC or GTCTAGGC sequences in the HDAC6 regulatory region and the GCCAAGAC sequence in the c-Jun promoter; Smad7 was found to bind to GGCAAGAC in the regulatory region of HDAC6 and to GCCAAGAC in the c-Jun promoter (Figures 2C and 2D). These sequences contain a 5′-AGAC-3′ motif, which is a known binding site for Smad3 and 4. In order to investigate whether the 5′-AGAC-3′ motif is needed for binding of Smad7, we designed deletion oligonucleotides lacking GGCA or AGAC and determined the binding of Smad7. Smad7 bound to the oligonucleotide lacking the 5′-AGAC-3′ element, but not to the oligonucleotide lacking 5′-GGCA-3′, indicating that the GGCA sequence, but not the AGAC sequence, is needed for the binding of Smad7 (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Smad7 Binds to a 5′-GGCA-3′Element in HDAC6 and 5′-GCCA-3′Element in c-Jun Regulatory Regions

(A and B) PC3U cells stimulated or not with TGF-β were lysed and ChIP assay was performed using a Smad7 antibody, or control rabbit (R) or goat (G) IgG, for immunoprecipitation, and primers recognizing HDAC6 regulatory region (A) and c-Jun promoter (B). Graphs are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA was used as the statistical test. ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(C and D) PC3U cells were stimulated or not with TGF-β and DNAP was performed by pull-down (PD) of biotinylated GTCTAGGC, GGCAAGAC (C) or GCCAAGAC (D) oligos by streptavidin-agarose, followed by immunoblotting (IB) for Smad7. No oligo was added in the PD step for the negative ctrl. The filter was reblotted for Smad2/3. HDAC6 oligos were analyzed by agarose electrophoresis gel (C).

(E) PC3U cells were stimulated, or not, with TGF-β and DNAP was performed by PD using biotinylated GGCAAGAC, Del AGAC, or Del GGCA HDAC6 oligos, followed by IB for Smad7. No oligo was added in the PD step for the negative ctrl. The filter was reblotted for Smad2/3. IB for Smad7 was performed on whole-cell lysates (WCL) as a control of the input levels.

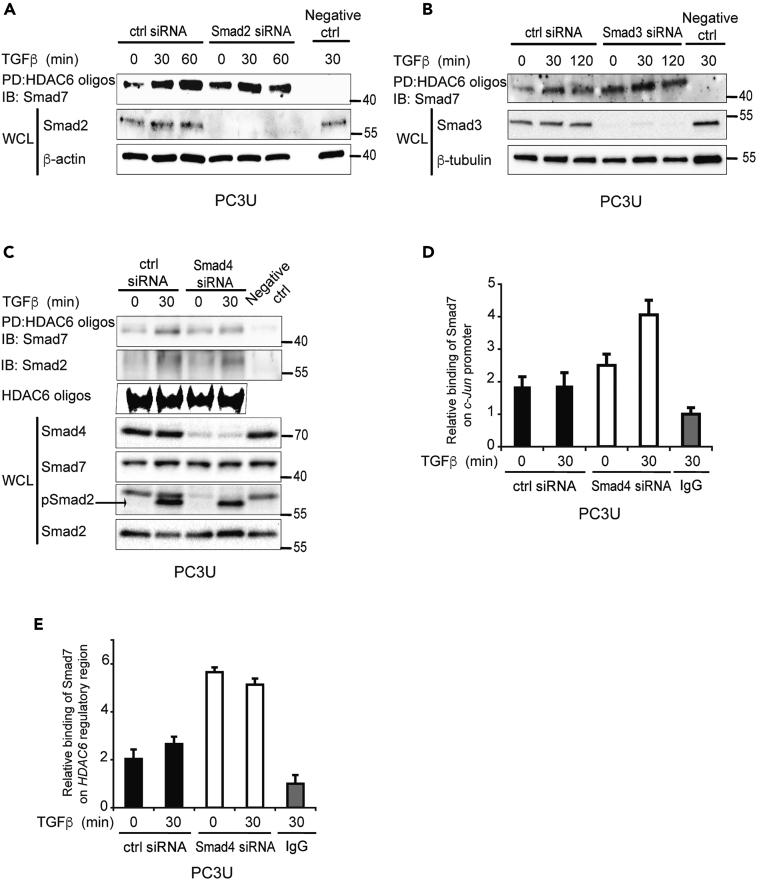

Smad2, 3, and 4 Are Not Required for Smad7 to Bind to DNA

As a Smad2/3/4-binding site was located adjacent to the Smad7-binding site in the c-Jun and HDAC6 regulatory regions, it is possible that the binding of Smad7 to DNA depends on Smad2, 3, or 4. To explore this possibility, DNAP was performed on the lysates from PC3U cells transfected with control siRNA and siRNA for Smad2, 3, or 4. Smad7 was found to bind to the HDAC6 regulatory region even in the absence of Smad2, 3, or 4 (Figures 3A–3C). ChIP assays using PC3U cells transfected with control, Smad2, Smad3 (Figures S3A and S3B), or Smad4 siRNA (Figures 3D and 3E) also showed that binding of Smad7 on the c-Jun and HDAC6 regulatory regions does not require Smad2, 3, or 4.

Figure 3.

Smad2, 3, and 4 Are Not Required for Smad7 to Bind to DNA

(A–C) Lysates from PC3U cells transfected with ctrl or Smad2 (A), Smad3 (B), or Smad4 (C) siRNA, and treated or not with TGF-β, were subjected to DNAP assay using biotinylated HDAC6 oligos for PD and Smad7 antibody for IB. DNAP filter was reblotted with Smad2 antibody (C) No oligo was added in the PD step for the negative ctrl. Corresponding WCLs were subjected to IB for Smad2 (A), Smad3 (B), Smad4, Smad2, pSmad2 (C). IB for Smad7 was performed on WCL as a control of the input levels (C). Biotinylated HDAC6 oligos with GGCAAGAC binding sites were run on an agarose electrophoresis gel (C).

(D and E) Lysates from PC3U cells transfected with ctrl or Smad4 siRNA, and treated or not with TGF-β, were subjected to ChIP with Smad7 or IgG ctrl antibody and RT-PCR with primers recognizing c-Jun promoter (D) or HDAC6 regulatory region (E). Graphs are means ± SEM from three independent experiments.

See also Figure S3.

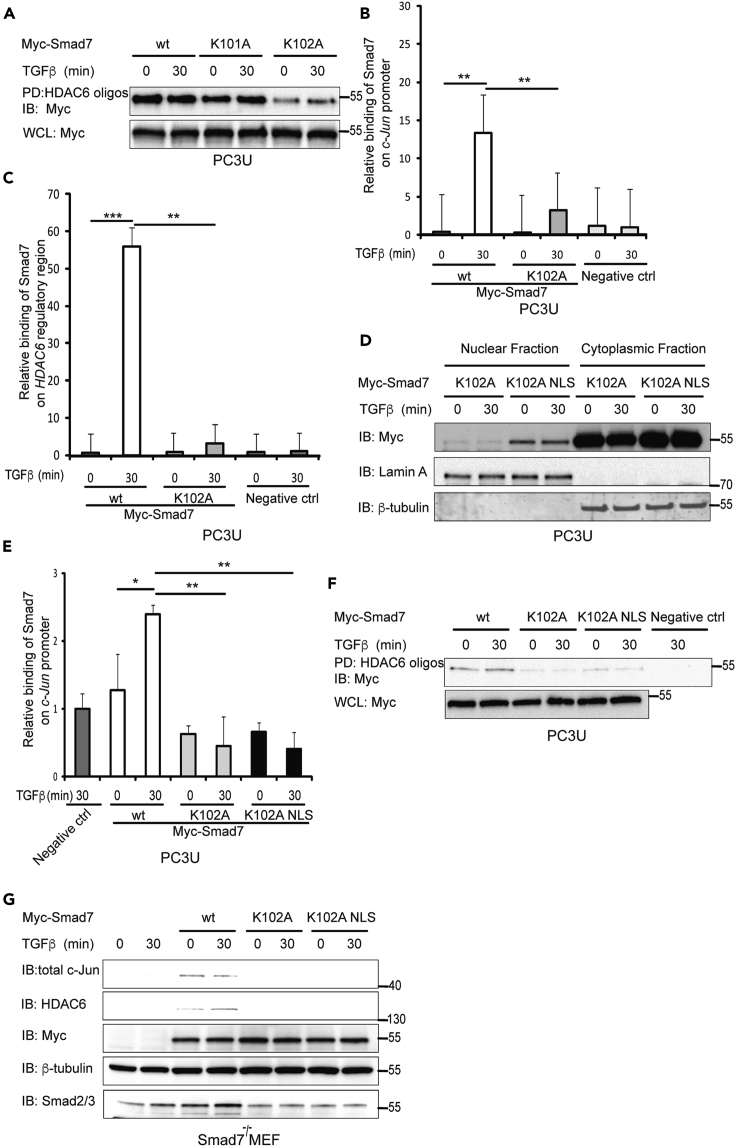

K102 of Smad7 Is Important for Binding to the HDAC6 and c-Jun Regulatory Regions

In order to identify possible DNA-binding epitopes in Smad7, we focused on basic amino acid residues in the region that are homologous with the DNA-binding region of Smad4, i.e., lysine 101 (K101) and K102. Each of the lysine residues were mutated to alanine residues and DNAP was performed in cells transfected with the different mutants. Mutation of K101 did not affect the binding of Smad7 to the regulatory region of HDAC6, whereas mutation of K102 to alanine reduced the binding, suggesting that this particular residue contributes to the efficient binding of Smad7 to DNA (Figure 4A). ChIP was also performed using lysates from cells transfected with wt Smad7, as well as K102A mutant Smad7; the results confirmed that wt Smad7 bound the regulatory regions of c-Jun and HDAC6 but the K102A mutant bound less efficiently (Figures 4B and 4C). As K102 is located in a putative nuclear localization signal (NLS) of Smad7, the K102A mutation may have disrupted the nuclear entry of mutant Smad7 and therefore decreased the binding to the c-Jun and HDAC6 regulatory regions. In order to assure an efficient nuclear translocation of the Smad7 K102A mutant, we fused an NLS sequence to the mutant construct. Cell fractionation showed that K102A Smad7 mutant supplemented with an NLS localized to the nucleus (Figure 4D). ChIP was performed to further examine the DNA-binding abilities of wt, as well as K102A and K102A-NLS mutant Smad7 on the c-Jun promoter. A reduced binding to the c-Jun promoter was observed for the mutants (Figure 4E). Moreover, DNAP was performed using PC3U cells transfected with wt Smad7, and Smad7 K102A and K102A-NLS mutants. wt Smad7 bound to the HDAC6 regulatory region, but the Smad7 K102A and K102A-NLS mutants did not (Figure 4F). Taken together with the results obtained by DNAP experiments, the results of the ChIP experiment showed that wt Smad7 bind to the promoter of c-Jun, whereas the K102A and K102A-NLS mutant Smad7 did not bind. To further elucidate the role of Smad7 in regulating the expression of c-Jun and HDAC6, the expressions of c-Jun and HDAC6 were determined by immunoblotting of lysates of Smad7−/− MEFs transfected by wt Smad7, or the K102A or K102A-NLS Smad7 mutants (Itoh et al., 1998). The expression of both c-Jun and HDAC6 was rescued by the transfection of wt Smad7 but not by the transfection of the Smad7 mutants (Figure 4G), demonstrating that Smad7 regulates these genes by directly binding to their regulatory regions.

Figure 4.

Lysine102 (K102) of Smad7 Is Important for Binding to the HDAC6 and c-Jun Regulatory Regions

(A) Cells transfected with wt Smad7, K101A or K102A mutant Smad7, and treated with TGF-β, were lysed and DNAP assay was performed on lysates using biotinylated HDAC6 oligos for PD and Myc antibody for IB. Corresponding WCLs were IB for Myc as a control for equal transfection.

(B and C) Cells were transfected with wt or K102A mutant Smad7 plasmids and treated or not with TGF-β and lysed. Cell lysates were subjected to ChIP using Smad7 or ctrl IgG antibodies for IP and primers recognizing c-Jun promoter (B) and HDAC6 regulatory region (C). Graphs are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA was used as the statistical test. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(D) PC3U cells transfected with K102A or K102A NLS mutants of Myc-Smad7 were treated or not with TGF-β and lysed. Lysates were subjected to cytoplasmic-nuclear fractionation followed by IB for Myc, Lamin A/C, and β-tubulin.

(E) Lysates from PC3U cells transfected with wt, K102A or K102A NLS mutant Myc-Smad7 and treated with TGF-β, were subjected to ChIP assay by using Smad7 or IgG control antibody for IP and primers recognizing c-Jun promoter for RT-PCR. Graphs are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA was used as the statistical test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

(F) Cells transfected with wt Smad7, K102A or K102A NLS mutants of Myc-Smad7, and treated with TGF-β, were lysed and DNAP assay was performed on lysates using biotinylated HDAC6 oligos for PD and Myc antibody for IB. Corresponding WCL were IB for Myc as a control for equal transfection.

(G) Smad7−/− MEFs transfected or not with wt Smad7, K102A or K102A NLS mutants of Myc-Smad7 plasmid and treated with TGF-β were lysed, and lysates were IB for c-Jun, HDAC6, Myc, β-tubulin, and Smad2/3.

Smad2/3 Binding to the HDAC6 and c-Jun Regulatory Regions Depends on Smad7

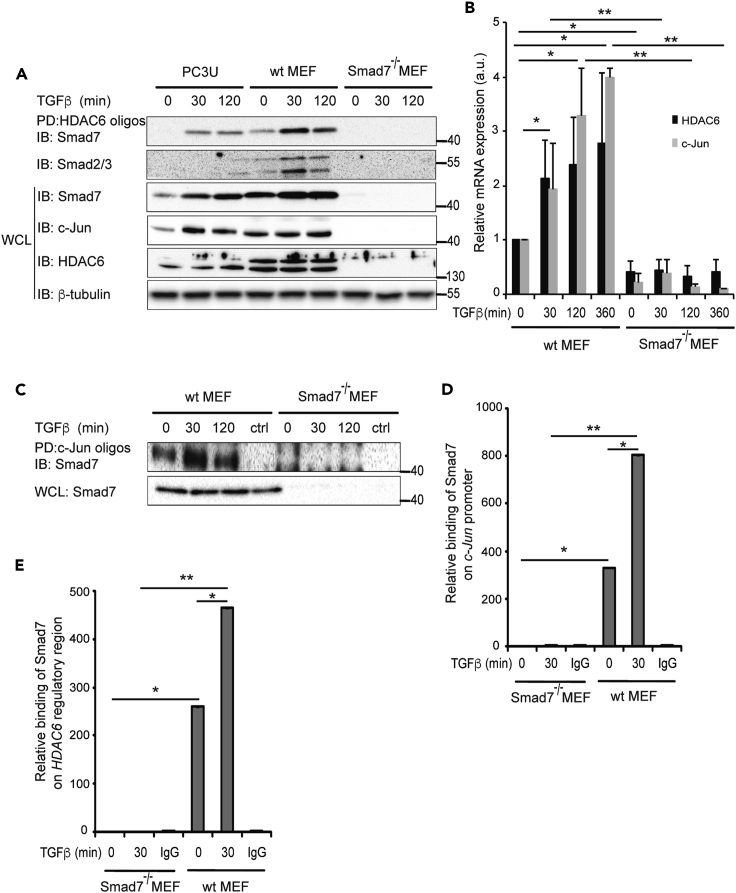

In order to further investigate the binding of Smad7 to the regulatory regions of HDAC6 and c-Jun, DNAP assays were performed using wt MEFs, as well as Smad7−/− MEFs; PC3U cells were used for comparison. Smad7, as well as Smad2/3, from PC3U cells and wt MEFs bound to HDAC6 oligos (Figure 5A). Smad2/3 binding was lost in Smad7−/− MEFs, suggesting that Smad7 is required for R-Smads to bind to the regulatory region of HDAC6. HDAC6 and c-Jun protein (Figure 5A) and c-Jun and HDAC6 mRNA (Figure 5B) expression was reduced significantly in Smad7−/− MEFs, suggesting that Smad7 binding to the regulatory regions is required for the expression of both c-Jun and HDAC6. Smad7 from wt MEFs bound to c-Jun oligos, but as expected, no binding was observed in Smad7−/− MEFs (Figure 5C). MEFs were also subjected to ChIP using a Smad7 antibody; Smad7 binding to the c-Jun and HDAC6 regulatory regions was observed in wt MEFs but, as expected, not in Smad7−/− MEFs (Figures 5D and 5E).

Figure 5.

Smad2/3 Binding to the HDAC6 and c-Jun Regulatory Regions Depends on Smad7

(A) PC3U, wt MEF cells, and Smad7−/− MEF cells were treated with TGF-β and lysates of the cells subjected to DNAP by HDAC6 oligos, followed by IB for Smad7. The same filter was reblotted with a Smad2/3 antibody. The corresponding cell lysates were IB for Smad7, c-Jun, HDAC6, and β-tubulin.

(B) After treatment with TGF-β, wt and Smad7−/− MEF cells were lysed and mRNA expression of c-Jun and HDAC6 were measured by RT-PCR.

(C) After treatment with TGF-β, wt and Smad7−/− MEF cells were lysed and DNAP was performed by PD with c-Jun oligos and IB for Smad7.

(D and E) wt and Smad7−/− MEF cells treated or not with TGF-β were exposed to ChIP assay with a Smad7 antibody or ctrl IgG and analyzed with RT-PCR using primers for the c-Jun promoter (D) or HDAC6 regulatory region (E).

Graphs are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA was used as the statistical test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

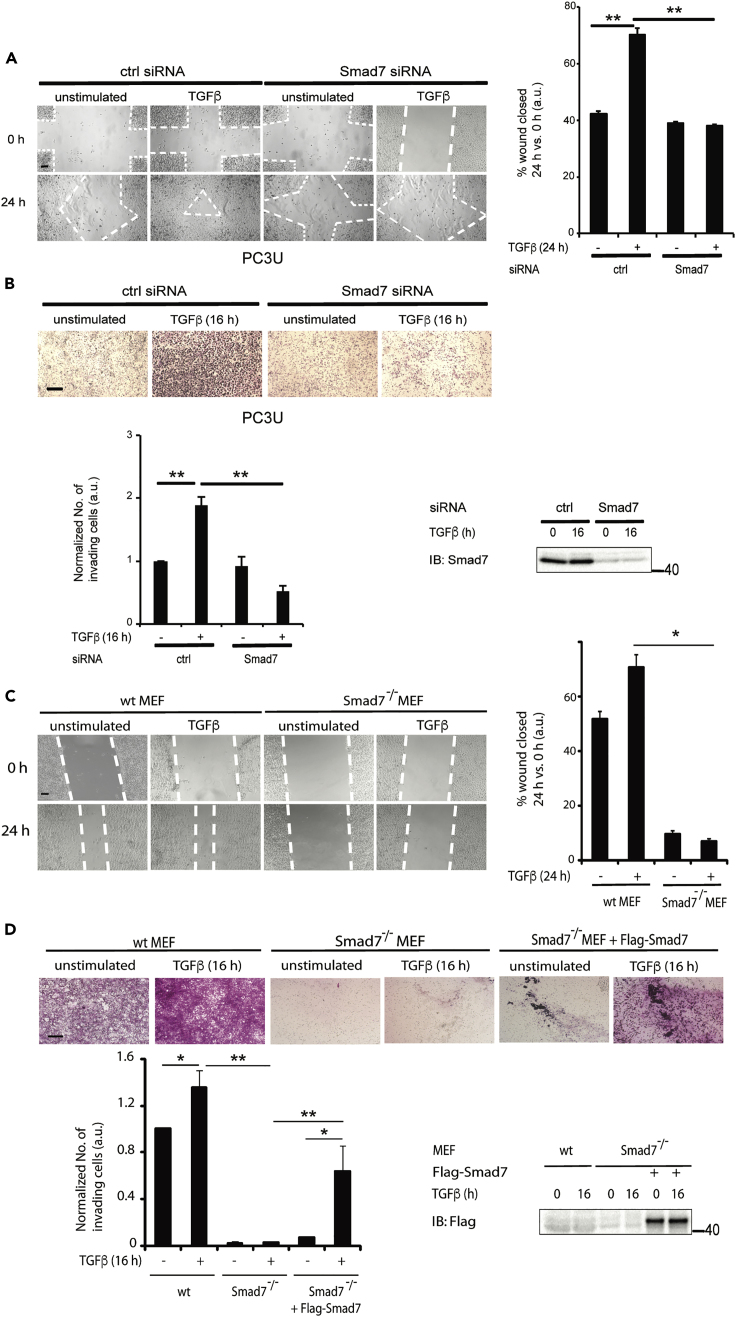

Smad7 and HDAC6 Promote TGF-β-Induced Invasion and Migration

To further validate a role for Smad7 in the regulation of TGF-β-induced migration and invasion, we investigated these responses in PC3U cells transfected with control or Smad7 siRNA. TGF-β-induced migration and invasion were abolished in cells in which Smad7 had been knocked down (Figures 6A and 6B), in line with our previous observations that Smad7 plays an important role for TGF-β-induced migration (Ekman et al., 2012). We further investigated these responses in wt and Smad7−/− MEFs. We observed a complete loss of TGF-β-induced migration of Smad7−/− MEFs in a cell culture scratch assay (Figure 6C). Moreover, TGF-β-induced invasion through a Matrigel-coated chamber was completely lost in Smad7−/− MEFs but was regained upon transfection of Smad7 (Figure 6D). From these data, we conclude that Smad7 is required for TGF-β-induced migration and invasion of MEFs.

Figure 6.

Smad7 and HDAC6 Promote TGF-β-Induced Invasion and Migration

(A) PC3U cells transfected with ctrl or Smad7 siRNA, were stimulated, or not, with TGF-β in a cell culture wound healing assay, as described in Methods.

(B) PC3U cells were subjected to an invasion assay for 16 h without or with TGF-β stimulation. Scale bar, 100 μM. Corresponding WCLs were exposed to IB with Smad7 antibody as a control.

(C) wt and Smad7−/− MEF cells were stimulated, or not, with TGF-β in a cell culture wound healing assay.

(D) wt, Smad7−/−, and Smad7-retransfected Smad7−/− MEF cells were subjected to an invasion assay for 16 h without or with TGF-β stimulation. Scale bar, 100 μM.

Graphs are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA was used as the statistical test ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

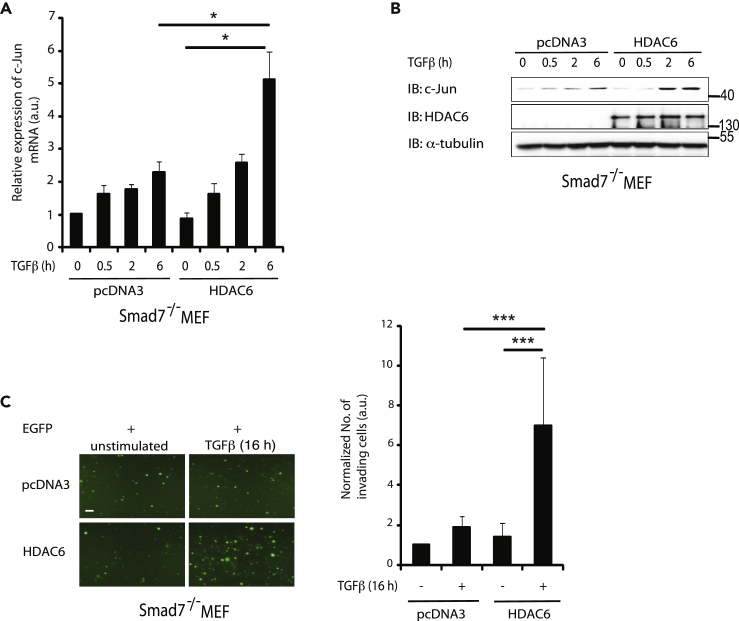

We have previously shown that c-Jun promotes invasion in prostate cancer cell (Thakur et al., 2014). Since Smad7 binds to the HDAC6 regulatory region (Figure 2A) and has a role in cell migration and invasion in response to TGF-β (Figures 6A–6D), we investigated whether c-Jun mRNA and protein expression are affected by HDAC6 transfection in Smad7−/− MEF cells. The TGF-β-induced increase in c-Jun mRNA (Figure 7A) and c-Jun protein (Figure 7B) was significantly higher in Smad7−/− MEFs transfected with HDAC6 than in control Smad7−/− MEFs. In order to further examine the role of HDAC6 in TGF-β-induced cell invasion, Smad7−/− MEF cells were co-transfected with EGFP and HDAC6, or pcDNA3 as a control. Cells transfected with HDAC6, visualized by the fluorescent signal of EGFP, showed increased invasion compared with pcDNA3-transfected control cells (Figure 7C). These data demonstrate that HDAC6 exerts its role downstream of Smad7.

Figure 7.

HDAC6 Acts Downstream of Smad7 to Promote c-Jun Expression and Invasion

(A and B) Smad7−/− cells transfected with pcDNA3 or HDAC6 plasmids and treated or not with TGF-β were lysed, and cell lysates were subjected to RT-PCR by using c-Jun primers (A) or IB for c-Jun, HDAC6, and α-tubulin (B).

(C) Smad7−/− cells transfected with EGFP and HDAC6 or pcDNA3 plasmids were stimulated or not with TGF-β and subjected to an invasion assay, as described in Methods. Scale bar, 100 μM.

Bar graph are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA was used as the statistical test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

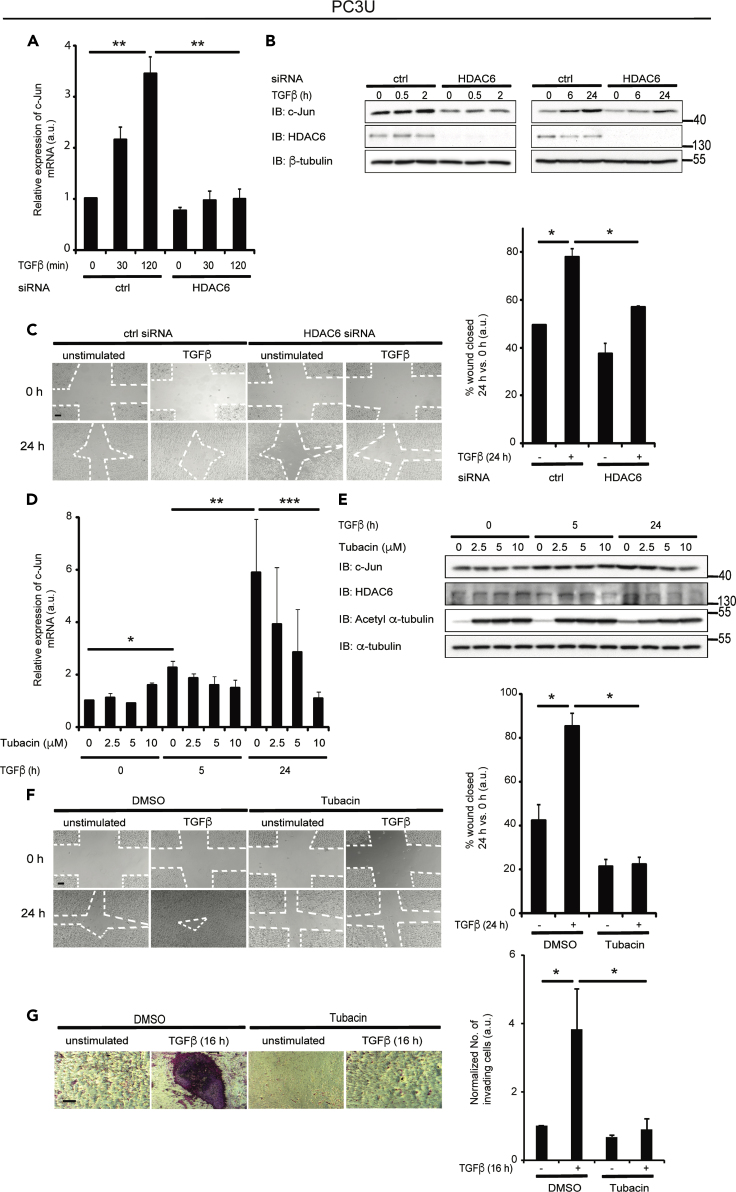

HDAC6 Is Required for TGF-β-Induced c-Jun-Mediated Migration and Invasion

We next investigated whether c-Jun mRNA and protein expression are dependent on HDAC6. HDAC6 knockdown by siRNA in PC3U cells resulted in decreased TGF-β-induced expression of c-Jun mRNA (Figure 8A) and c-Jun protein (Figure 8B). In a scratch assay, HDAC6 siRNA-transfected PC3U cells migrated slower than control siRNA-transfected cells in response to TGF-β (Figure 8C). To further investigate the role of HDAC6 in TGF-β-induced, c-Jun-dependent migration and invasion, PC3U cells were treated with increasing concentrations of tubacin, an HDAC6 inhibitor, added before TGF-β stimulation. TGF-β-induced mRNA expression of c-Jun was suppressed by tubacin treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 8D), and the amount of c-Jun protein was decreased at high doses of tubacin after 24 h of TGF-β stimulation in PC3U (Figure 8E), as well as LNCaP (Figure S1C) and DU145 (Figure S2C) cells. PC3U cells treated with tubacin, or DMSO as a control, prior to TGF-β stimulation, were subjected to scratch (Figure 8F) and invasion (Figure 8G) assays. Treatment of cells with tubacin inhibited TGF-β-induced closure of the wound, whereas the wound closed in the control cell culture (Figure 8F). Similarly, TGF-β-induced invasion of PC3U cells was significantly decreased by tubacin treatment (Figure 8G). Two additional prostate cancer cells, LNCaP (Figure S1D) and DU145 (Figure S2D), also showed decreased TGF-β-induced invasion by tubacin treatment. These results suggest that HDAC6 is required for the TGF-β-induced c-Jun-mediated migration in prostate cancer cells.

Figure 8.

HDAC6 Is Required for TGF-β-Induced c-Jun-Mediated Migration and Invasion

(A and B) PC3U cells transfected with control or HDAC6 siRNA and treated or not with TGF-β were lysed, and cell lysates were subjected to RT-PCR by using c-Jun primers (A), and IB for c-Jun, HDAC6, and β-tubulin (B).

(C) PC3U cells transfected with ctrl or HDAC6 siRNA were stimulated or not with TGF-β in a scratch assay, as described in Methods. Scale bar, 100 μM.

(D) PC3U cells were treated or not with 2.5, 5, and 10 μM tubacin prior to TGF-β stimulation, and mRNA expression of c-Jun was measured by RT-PCR.

(E) The corresponding WCLs were subjected to IB using antibodies against c-Jun, HDAC6, acetyl α-tubulin, and α-tubulin.

(F) After treatment with DMSO or 2.5 μM tubacin, PC3U cells were stimulated, or not, with TGF-β and subjected to a wound healing assay, as described in Methods. Scale bar, 100 μM.

(G) PC3U cells were subjected to an invasion assay for 16 h without or with TGF-β stimulation and without or with tubacin. Scale bar, 100 μM.

Bar graph are means ± SEM from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA was used as the statistical test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

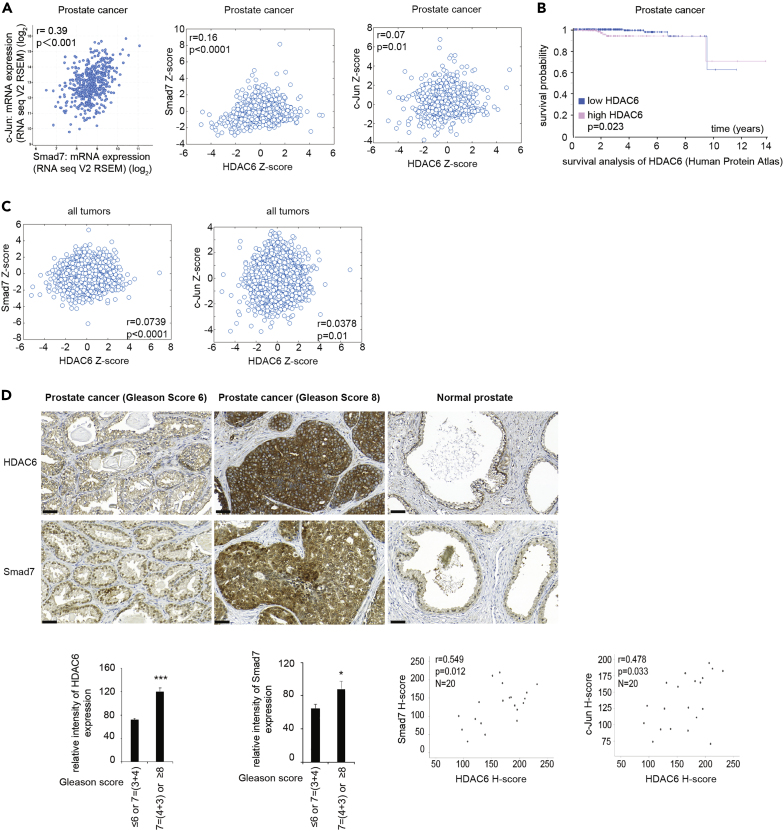

High Expression of Smad7, c-Jun, and HDAC6 is Correlated with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Prostate Cancer

To investigate the clinical relevance of our findings, we used the cBioPortal database from TCGA. We found a positive correlation between Smad7 and c-Jun mRNA, Smad7 and HDAC6 mRNA, and c-Jun and HDAC6 mRNA (Figure 9A) in tumor material from patients with prostate cancer. Notably, high expression of HDAC6 mRNA correlated with poor prognosis for patients with prostate cancer (Figure 9B), whereas no significant correlation between Smad7 mRNA expression or c-Jun mRNA expression and poor prognosis for patients with prostate cancer was observed (data not shown). Moreover, we also observed a positive correlation between Smad7 and HDAC6 mRNA, and c-Jun and HDAC6 mRNA in several various cancer forms (Figure 9C). The expression of HDAC6, Smad7, and c-Jun was examined by immunohistochemistry in tissue sections from patients with prostate cancer and in tissue sections from normal prostate gland. A significantly increased expression of HDAC6, Smad7, and c-Jun was observed in prostate cancer tissues with Gleason score ≥8 (including Gleason score 4 + 3) as compared with lower Gleason score ≤6 or 7 (including Gleason score 3 + 4), demonstrating that high expression of these proteins is correlated with prostate cancer progression. Moreover, a high co-expression of Smad7 and HDAC6, and c-Jun and HDAC6 was also observed in prostate cancer tissues, which correlated with poor prognosis (Figure 9D). The expression of both HDAC6 and Smad7 was found in basal epithelial cells in the normal prostate gland (Figure 9D). Smad7 expression has been reported to be localized in basal epithelial cells in the prostate gland in a murine prostate cancer model (Brodin et al., 1999), in line with our current observations. From these data, we conclude that the expression of HDAC6, Smad7, and c-Jun correlates with poor prognosis for patients with prostate cancer. Notably, a correlation between expression of Smad7 mRNA and both c-Jun and HDAC6 mRNA can also be seen in clinical material from patients with colorectal carcinoma, and high levels of HDAC6 mRNA correlate with poor survival (Figure S4).

Figure 9.

High Expression of Smad7, c-Jun, and HDAC6 Is Correlated with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Prostate Cancer

(A) The dot plots show positive correlations between expression of mRNA of Smad7 and c-Jun, Smad7 and HDAC6; and Jun and HDAC6 in prostate cancer. Data were obtained from cBioPortal TCGA PanCancer Atlas databases in which log2 fold change (RNA seq V2 RSEM) and Z score are shown. p Value-Bootstrap hypothesis and Pearson correlation coefficient (r) are presented.

(B) Kaplan Meier plot showing the survival probability of patients with prostate cancer categorized based on high and low expression of HDAC6 mRNA. Representative image obtained from Human Protein Atlas.

(C) The dot plots show positive correlations between expression of mRNA of Smad7 and HDAC6; and Jun and HDAC6 in all forms of cancer.

(D) Prostate tumor tissue samples were stained with HDAC6, Smad7, and c-Jun antibodies. Quantification shows the means ± SEM of ten patients in each group. Mann-Whitney U test was used. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Scale bar, 50 μm. The scatterplots show the positive correlations between Smad7 and HDAC6 protein, c-Jun, and HDAC6 proteins, respectively, in prostate cancer tissues. r = Pearson's coefficient test.

See also Figure S4.

Discussion

We report here that Smad7, a classical TGF-β target gene so far recognized mainly as a negative regulator of TGF-β signaling, also can act in the nucleus as a positive regulator of transcription of two tumor-promoting genes, which are linked to tumor invasion. We show herein that Smad7 binds to the regulatory regions of the HDAC6 and c-Jun genes thereby promoting their expression in response to TGF-β. Using Hep3B cells, in which Smad7 is predominantly located in the nuclei regardless of TGF-β stimulation, Zhang et al. (2007) previously showed that forced expression of Smad7 repressed the transcriptional activity of TGF-β, suggesting that the effect of Smad7 on transcription varies between different cell lines. It is possible that the interaction between Smad7 and various partners differ in a contextual and kinetic manner after TGF-β stimulation, which can explain why Smad7 can act both as a positive and a negative regulator. The level of Smad7 may also be controlled in a contextual manner. For instance, Smad7 interacts with p300 via its MH2 domain leading to the acetylation by p300 at K64 and K70 in the N terminus of Smad7 (Gronroos et al., 2002). Acetylation at these lysines prevents the ubiquitination and degradation of Smad7. Smad7 also interacts, via its MH2 domain, with transcriptional repressors, such as HDACs, promoting its deacetylation, ubiquitination, and degradation. It has been reported that the other I-Smad, Smad6, forms a complex with phosphorylated Smad1, thereby inhibiting BMP signaling by disrupting the formation of a functional R-Smad-co-Smad complex. Smad6 acts as a transcriptional repressor by interacting with Hoxc-8 or by binding to DNA and recruiting transcriptional repressors like HDACs or CtBP to inhibit the transcription of target genes (Bai and Cao, 2002).

TGF-β induces the expression of Smad7 in the murine interleukin-2 (IL-2)-dependent T-lymphoma cell line CTLL2, which has high expression of the transcription factor ZEB1 and low or no expression of Smad7. In these cells, Smad7 binds to Smad responsive elements (SREs) upon TGF-β stimulation (Nakahata et al., 2010). A complex consisting of ZEB1, Smad7, R-Smads, and p300 is recruited to the SRE, leading to the activation of TGF-β target genes, including Pai1 and p21. This study, showing a role for Smad7 in a transcriptionally active complex leading to enhanced TGF-β signaling, supports our findings that Smad7 binds to DNA and may also promote the binding of R-Smads to specific regions of DNA.

Using ChIP and DNAP, we mapped the binding site for Smad7 to 5′-GGCA-3′and 5′-GCCA-3′ motifs in the regulatory region of HDAC6 and c-Jun, respectively. The Smad7-binding sites are adjacent to the Smad3 and Smad4 binding motif (5′-AGAC-3′). Zhang et al. (2007) previously reported that Smad7 binds to DNA directly via its MH2 domain. In contrast, our results suggest that K102 in the N-terminal region of Smad7 is important for binding to the HDAC6 and c-Jun regulatory regions. The effect of Smad7 on transcription might be facilitated by the MH2-domain, which is known to bind to the transcriptional coregulator p300. The identification of Smad7 as a part of a transcriptional complex together with Smad2, 3, and 4 is particularly interesting in relation to the fact that Smads have low affinity for binding to DNA. Future studies will answer the question whether Smad7 promotes the regulation of other specific target genes besides c-Jun and HDAC6, in response to growth factor stimulation of cells. Furthermore, studies of the relation between the identified Smad7-binding sites and the recently identified additional binding motif for both TGF-β and BMP Smads, i.e., GGC(GC)|(CG) (Martin-Malpartida et al., 2017), will also be of importance to better understand the contextual regulation of gene expression in response to TGF-β stimulation of cells.

We have previously reported that TGF-β activates TRAF6 in PC3U cells causing activation of the p38 MAPK pathway leading to apoptosis (Sorrentino et al., 2008) and subsequent activation of c-Jun, promoting migration and invasion (Thakur et al., 2014). In this pathway, Smad7 acts as an adaptor protein facilitating TGF-β-induced activation of the JNK and p38-MAPK pathways (Sorrentino et al., 2008). These findings, together with the observations in the present study, suggest that Smad7 can exert its protumorigenic functions both as an effector of activation of non-canonical TRAF6-mediated responses and by regulation of gene transcription, in a manner dependent on its subcellular localization.

Smad7 has previously been found to be amplified in colorectal carcinoma, and this event is linked to poor prognosis for these patients (Boulay et al., 2003). Moreover, knockdown of Smad7 expression in a human colorectal carcinoma xenograft model has been shown to reduce tumor growth in vivo (Stolfi et al., 2014), giving further evidence for a tumor-promoting role of Smad7 in colorectal cancer. However, other studies have reported a dual role of Smad7 expression in colorectal cancer, in line with the dual role of TGF-β in other cancer types (Stolfi et al., 2013). In the current study, we report that Smad7 promotes expression of HDAC6 in prostate cancer cells. High expression of HDAC6 is significantly linked to poor prognosis for the patients with prostate cancer (Figure 9D), as well as colorectal cancer (Figure S4). Moreover, a high co-expression of Smad7 and HDAC6, and c-Jun and HDAC6, was observed in prostate cancer tissues, which correlated with poor prognosis (Figure 9D). We have recently reported that both TβRI and c-Jun are expressed at high levels in aggressive prostate cancer tissues (Gudey et al., 2017), and high levels of Smad7 have been reported to be expressed in prostate cancer bone metastases (Nordstrand et al., 2018), providing support for the notion that active TGF-β signaling promotes prostate cancer progression and metastases, in line with our observations in this report.

Histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) is a unique isoform of the HDAC family, which is overexpressed in some cancers, such as bladder cancer, malignant melanoma, and lung cancer (Li et al., 2018). Since HDAC6 regulates cell proliferation, metastasis, invasion, and mitosis in tumors (Lafarga et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2008; Wickstrom et al., 2010), several isoform-specific inhibitors of the enzymatic activity of HDAC6 have been developed and analyzed in clinical trials (Chuang et al., 2013; Seidel et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2018). We identified previously that c-Jun, a member of AP-1 transcription factors, is activated by TGF-β in a TRAF6-dependent manner leading to invasion of prostate cancer cells (Thakur et al., 2014) and that the Smad7-APC complex links TβRI to the microtubule system to promote migratory responses of prostate cancer cells (Ekman et al., 2012).

The fact that HDAC6 promotes migration and metastasis of cancer cells has made HDAC6 an interesting cancer drug target (Dallavalle et al., 2012). HDAC6 has unique features among HDAC isoforms in terms of its cytoplasmic localization and non-histone substrates. Since pan-HDAC inhibitors show a number of toxic effects, selective HDAC6 inhibitors, which have fewer side effects, may therefore be a preferred therapeutic option (Li et al., 2018). Anti-tumor effects of HDAC6-specific inhibitors on prostate cancer cells have been observed (Chuang et al., 2013; Seidel et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2018); however, the role of TGF-β and its connection to HDAC6 in prostate cancer progression have not been addressed before. In this study, we find that HDAC6 is acting downstream of Smad7 as overexpression of HDAC6 in Smad7-deficient MEFs increased c-Jun expression and their invasive capability (Figure 7). Moreover, treatment of prostate cancer cells with tubacin, an HDAC6 inhibitor, in a dose-dependent manner completely inhibited TGF-β-induced expression of c-Jun mRNA, as well as migration and invasion (Figures 8, S1C, S1D, S1G, and S1H), giving further experimental evidence for the important role for HDAC6 in TGF-β-induced migration and invasiveness of cancer cells and support for the potential usefulness of HDAC6 inhibitors for patients with aggressive prostate cancer. Our identification of HDAC6 as a downstream target gene of Smad7 in response to TGF-β is therefore of clinical importance for patients with prostate cancer, as HDAC6-inhibitors are currently investigated for their effects on cancer cells in clinical trials (Wang et al., 2018).

In summary, we have described a novel role for Smad7 as a transcriptional regulator of c-Jun and HDAC6 in prostate cancer cells, promoting migration and invasion. Smad7 was shown to promote recruitment of R-Smad-Smad4 complexes to DNA, thus presenting a previously unknown function for Smad7. The TGF-β- and Smad7-induced increases of c-Jun and HDAC6 promote invasion of prostate cancer cells, making it relevant to investigate expression of Smad7, c-Jun, and HDAC6 in clinical tissue samples of patients with prostate cancer as potential biomarkers and drug targets.

Limitation of the Study

The present study does not contain any investigation of the findings in an animal model. For instance, a mouse study in which the growth and invasion of prostate cancer cells, with or without knockdown of Smad7, HDAC6, or c-Jun, is missing.

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Marene Landström (Marene.Landstrom@umu.se).

Materials Availability

We generated Smad7-mutant plasmids for this study as described in this article; contact Lead Contact (as described above).

Data and Code Availability

Public databases were used in our study as described in Transparent Methods.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nikolay Aksenov at Department of Medical Biosciences, Umeå University (former postdoc in M.L. group) for assistance with information gained by using bioinformatics and Yang Zhou at Department of Medical Biosciences, Umeå University for immunohistochemical stainings with c-Jun antibodies. We appreciate comments and fruitful scientific discussions with members of our research groups at Uppsala University and Umeå University. We are also grateful for the excellent technical assistance provided by Pernilla Andersson at Department of Medical Biosciences, Umeå University, Sweden.

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (K2019-01598 to M.L.; 2015-02756), the Swedish Cancer Society (CAN 2017/544 contract number 18 0491 to M.L.; 2016/445). ALF-VLL-464591 and ALF-VLL-583901 Financial support was also provided to ML through a regional agreement between Umeå University and Region Västerbotten (RV; ALF); RV 933125, RV 738911, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (2012.0090), Prostatacancerförbundet and Novo Nordisk Foundation XPS Extension Grant #59307, Kempe Foundation, Konung Gustaf V:s och Drottning Victorias Frimurarestiftelse, Lion's Cancer Research Foundation and Umeå University. The European Research Council (787472) to C-H.H. N.T. was in part supported by the Swedish Cancer Society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.T., A.H., C-H.H., M.L.; Methodology, N.T., A.H., J.S.; Resources, S.I., A.B.; Writing – Original Draft, N.T., A.H.; Writing – Review & Editing, A.H., J.S., C.-H.H., M.L., A.B.; Funding Acquisition, M.L., C.-H.H.; Supervision, M.L., C.-H.H.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: September 3, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101470.

Contributor Information

Carl-Henrik Heldin, Email: c-h.heldin@imbim.uu.se.

Maréne Landström, Email: marene.landstrom@umu.se.

Supplemental Information

References

- Afrakhte M., Moren A., Jossan S., Itoh S., Sampath K., Westermark B., Heldin C.H., Heldin N.E., ten Dijke P. Induction of inhibitory Smad6 and Smad7 mRNA by TGF-beta family members. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;249:505–511. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahel J., Hudorovic N., Vicic-Hudorovic V., Nikles H. Tgf-Beta in the natural history of prostate cancer. Acta Clin. Croat. 2019;58:128–138. doi: 10.20471/acc.2019.58.01.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragon E., Wang Q., Zou Y., Morgani S.M., Ruiz L., Kaczmarska Z., Su J., Torner C., Tian L., Hu J. Structural basis for distinct roles of SMAD2 and SMAD3 in FOXH1 pioneer-directed TGF-beta signaling. Genes Dev. 2019;33:1506–1524. doi: 10.1101/gad.330837.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assinder S.J., Dong Q., Kovacevic Z., Richardson D.R. The TGF-beta, PI3K/Akt and PTEN pathways: established and proposed biochemical integration in prostate cancer. Biochem. J. 2009;417:411–421. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai S., Cao X. A nuclear antagonistic mechanism of inhibitory Smads in transforming growth factor-beta signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:4176–4182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierie B., Moses H.L. Tumour microenvironment: TGFbeta: the molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:506–520. doi: 10.1038/nrc1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay J.L., Mild G., Lowy A., Reuter J., Lagrange M., Terracciano L., Laffer U., Herrmann R., Rochlitz C. SMAD7 is a prognostic marker in patients with colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2003;104:446–449. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodin G., ten Dijke P., Funa K., Heldin C.H., Landstrom M. Increased smad expression and activation are associated with apoptosis in normal and malignant prostate after castration. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2731–2738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budi E.H., Duan D., Derynck R. Transforming growth factor-beta receptors and Smads: regulatory complexity and functional versatility. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:658–672. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang M.J., Wu S.T., Tang S.H., Lai X.M., Lai H.C., Hsu K.H., Sun K.H., Sun G.H., Chang S.Y., Yu D.S. The HDAC inhibitor LBH589 induces ERK-dependent prometaphase arrest in prostate cancer via HDAC6 inactivation and down-regulation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallavalle S., Pisano C., Zunino F. Development and therapeutic impact of HDAC6-selective inhibitors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012;84:756–765. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielpour D. Transdifferentiation of NRP-152 rat prostatic basal epithelial cells toward a luminal phenotype: regulation by glucocorticoid, insulin-like growth factor-I and transforming growth factor-beta. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 2):169–179. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielpour D. Functions and regulation of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) in the prostate. Eur. J. Cancer. 2005;41:846–857. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R., Akhurst R.J. Differentiation plasticity regulated by TGF-beta family proteins in development and disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:1000–1004. doi: 10.1038/ncb434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z., Wu C.J., Chu G.C., Xiao Y., Ho D., Zhang J., Perry S.R., Labrot E.S., Wu X., Lis R. SMAD4-dependent barrier constrains prostate cancer growth and metastatic progression. Nature. 2011;470:269–273. doi: 10.1038/nature09677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund S., Bu S., Schuster N., Aspenstrom P., Heuchel R., Heldin N.E., ten Dijke P., Heldin C.H., Landstrom M. Transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta)-induced apoptosis of prostate cancer cells involves Smad7-dependent activation of p38 by TGF-beta-activated kinase 1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:529–544. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-03-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman M., Mu Y., Lee S.Y., Edlund S., Kozakai T., Thakur N., Tran H., Qian J., Groeden J., Heldin C.H. APC and Smad7 link TGFbeta type I receptors to the microtubule system to promote cell migration. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2012;23:2109–2121. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-12-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falzarano S.M., Ferro M., Bollito E., Klein E.A., Carrieri G., Magi-Galluzzi C. Novel biomarkers and genomic tests in prostate cancer: a critical analysis. Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 2015;67:211–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronroos E., Hellman U., Heldin C.H., Ericsson J. Control of Smad7 stability by competition between acetylation and ubiquitination. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:483–493. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00639-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudey S.K., Sundar R., Heldin C.H., Bergh A., Landstrom M. Pro-invasive properties of Snail1 are regulated by sumoylation in response to TGFbeta stimulation in cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:97703–97726. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudey S.K., Sundar R., Mu Y., Wallenius A., Zang G., Bergh A., Heldin C.H., Landstrom M. TRAF6 stimulates the tumor-promoting effects of TGFbeta type I receptor through polyubiquitination and activation of presenilin 1. Sci. Signal. 2014;7:ra2. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamidi A., Song J., Thakur N., Itoh S., Marcusson A., Bergh A., Heldin C.H., Landstrom M. TGF-beta promotes PI3K-AKT signaling and prostate cancer cell migration through the TRAF6-mediated ubiquitylation of p85alpha. Sci. Signal. 2017;10:eaal4186. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aal4186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanyu A., Ishidou Y., Ebisawa T., Shimanuki T., Imamura T., Miyazono K. The N domain of Smad7 is essential for specific inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:1017–1027. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H., Abdollah S., Qiu Y., Cai J., Xu Y.Y., Grinnell B.W., Richardson M.A., Topper J.N., Gimbrone M.A., Jr., Wrana J.L. The MAD-related protein Smad7 associates with the TGFbeta receptor and functions as an antagonist of TGFbeta signaling. Cell. 1997;89:1165–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin C.H., Miyazono K., ten Dijke P. TGF-beta signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature. 1997;390:465–471. doi: 10.1038/37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin C.H., Moustakas A. Signaling receptors for TGF-beta family members. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016;8:a022053. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh S., Landstrom M., Hermansson A., Itoh F., Heldin C.H., Heldin N.E., ten Dijke P. Transforming growth factor beta1 induces nuclear export of inhibitory Smad7. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:29195–29201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.29195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I.Y., Ahn H.J., Lang S., Oefelein M.G., Oyasu R., Kozlowski J.M., Lee C. Loss of expression of transforming growth factor-beta receptors is associated with poor prognosis in prostate cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 1998;4:1625–1630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H., Lee J., Song R., Hwang S.I., Lee J., Kim Y.H., Lee H.J. In vitro and in vivo imaging of prostate cancer angiogenesis using anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 antibody-conjugated quantum dot. Korean J. Radiol. 2013;14:30–37. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2013.14.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafarga V., Aymerich I., Tapia O., Mayor F., Jr., Penela P. A novel GRK2/HDAC6 interaction modulates cell spreading and motility. EMBO J. 2012;31:856–869. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.M., Timme T.L., Thompson T.C. Resistance to lysis by cytotoxic T cells: a dominant effect in metastatic mouse prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1927–1933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.S., Lim K.H., Guo X., Kawaguchi Y., Gao Y., Barrientos T., Ordentlich P., Wang X.F., Counter C.M., Yao T.P. The cytoplasmic deacetylase HDAC6 is required for efficient oncogenic tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7561–7569. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Zhang C., Hassan S., Liu X., Song F., Chen K., Zhang W., Yang J. Histone deacetylase 6 in cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018;11:111. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0654-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Malpartida P., Batet M., Kaczmarska Z., Freier R., Gomes T., Aragon E., Zou Y., Wang Q., Xi Q., Ruiz L. Structural basis for genome wide recognition of 5-bp GC motifs by SMAD transcription factors. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:2070. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02054-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. TGFbeta in cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. TGFbeta signalling in context. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:616–630. doi: 10.1038/nrm3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa M., Derynck R., Miyazono K. TGF-beta and the TGF-beta family: context-dependent roles in cell and tissue physiology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016;8:a021873. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Y., Gudey S.K., Landstrom M. Non-Smad signaling pathways. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Y., Sundar R., Thakur N., Ekman M., Gudey S.K., Yakymovych M., Hermansson A., Dimitriou H., Bengoechea-Alonso M.T., Ericsson J. TRAF6 ubiquitinates TGFbeta type I receptor to promote its cleavage and nuclear translocation in cancer. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:330. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahata S., Yamazaki S., Nakauchi H., Morishita K. Downregulation of ZEB1 and overexpression of Smad7 contribute to resistance to TGF-beta1-mediated growth suppression in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Oncogene. 2010;29:4157–4169. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo A., Navaratnam A., Andrews P. Prostate cancer and the role of biomarkers. Abdom. Radiol. (N. Y.) 2019;45:2120–2132. doi: 10.1007/s00261-019-02305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrand A., Bovinder Ylitalo E., Thysell E., Jernberg E., Crnalic S., Widmark A., Bergh A., Lerner U.H., Wikstrom P. Bone cell activity in clinical prostate cancer bone metastasis and its inverse relation to tumor cell androgen receptor activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:1223. doi: 10.3390/ijms19041223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partin A.W., Hanks G.E., Klein E.A., Moul J.W., Nelson W.G., Scher H.I. Prostate-specific antigen as a marker of disease activity in prostate cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2002;16:1218–1224. discussion 1224, 1227-1218 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu H., Begemann D.E., Kyprianou N. Aberrant TGF-beta signaling drives castration-resistant prostate cancer in a male mouse model of prostate tumorigenesis. Endocrinology. 2017;158:1612–1622. doi: 10.1210/en.2017-00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardelli C., Choong C.S., Buchanan G., Vivekanandan S., Neufing P., Stahl J., Marshall V.R., Horsfall D.J., Tilley W.D. Androgen receptor levels in prostate cancer epithelial and peritumoral stromal cells identify non-organ confined disease. Prostate. 2005;63:19–28. doi: 10.1002/pros.20154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salm S.N., Burger P.E., Coetzee S., Goto K., Moscatelli D., Wilson E.L. TGF-{beta} maintains dormancy of prostatic stem cells in the proximal region of ducts. J. Cell Biol. 2005;170:81–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel C., Schnekenburger M., Mazumder A., Teiten M.H., Kirsch G., Dicato M., Diederich M. 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid derivatives as HDAC6-specific inhibitors modulating microtubular structure and HSP90alpha chaperone activity against prostate cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016;99:31–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariat S.F., Kattan M.W., Traxel E., Andrews B., Zhu K., Wheeler T.M., Slawin K.M. Association of pre- and postoperative plasma levels of transforming growth factor beta(1) and interleukin 6 and its soluble receptor with prostate cancer progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:1992–1999. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0768-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino A., Thakur N., Grimsby S., Marcusson A., von Bulow V., Schuster N., Zhang S., Heldin C.H., Landstrom M. The type I TGF-beta receptor engages TRAF6 to activate TAK1 in a receptor kinase-independent manner. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:1199–1207. doi: 10.1038/ncb1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolfi C., De Simone V., Colantoni A., Franze E., Ribichini E., Fantini M.C., Caruso R., Monteleone I., Sica G.S., Sileri P. A functional role for Smad7 in sustaining colon cancer cell growth and survival. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1073. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolfi C., Marafini I., De Simone V., Pallone F., Monteleone G. The dual role of Smad7 in the control of cancer growth and metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:23774–23790. doi: 10.3390/ijms141223774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stravodimos K., Constantinides C., Manousakas T., Pavlaki C., Pantazopoulos D., Giannopoulos A., Dimopoulos C. Immunohistochemical expression of transforming growth factor beta 1 and nm-23 H1 antioncogene in prostate cancer: divergent correlation with clinicopathological parameters. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:3823–3828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur N., Gudey S.K., Marcusson A., Fu J.Y., Bergh A., Heldin C.H., Landstrom M. TGFbeta-induced invasion of prostate cancer cells is promoted by c-Jun-dependent transcriptional activation of Snail1. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:2400–2414. doi: 10.4161/cc.29339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velonas V.M., Woo H.H., dos Remedios C.G., Assinder S.J. Current status of biomarkers for prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:11034–11060. doi: 10.3390/ijms140611034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.X., Wan R.Z., Liu Z.P. Recent advances in the discovery of potent and selective HDAC6 inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;143:1406–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickstrom S.A., Masoumi K.C., Khochbin S., Fassler R., Massoumi R. CYLD negatively regulates cell-cycle progression by inactivating HDAC6 and increasing the levels of acetylated tubulin. EMBO J. 2010;29:131–144. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikstrom P., Stattin P., Franck-Lissbrant I., Damber J.E., Bergh A. Transforming growth factor beta1 is associated with angiogenesis, metastasis, and poor clinical outcome in prostate cancer. Prostate. 1998;37:19–29. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980915)37:1<19::aid-pros4>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.W., Hsu K.C., Lee H.Y., Huang T.C., Lin T.E., Chen Y.L., Sung T.Y., Liou J.P., Hwang-Verslues W.W., Pan S.L. A novel dual HDAC6 and tubulin inhibitor, MPT0B451, displays anti-tumor ability in human cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:205. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M., Fatyol K., Jin C., Wang X., Liu Z., Zhang Y.E. TRAF6 mediates Smad-independent activation of JNK and p38 by TGF-beta. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Fei T., Zhang L., Zhang R., Chen F., Ning Y., Han Y., Feng X.H., Meng A., Chen Y.G. Smad7 antagonizes transforming growth factor beta signaling in the nucleus by interfering with functional Smad-DNA complex formation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:4488–4499. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01636-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Public databases were used in our study as described in Transparent Methods.