Abstract

Background: Women diagnosed with gestational diabetes or preeclampsia are at a greater risk of developing future type 2 diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease. Increased perception of future chronic disease risk is positively associated with making health behavior changes, including in pregnant women. Although gestational diabetes is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes, few women have heightened risk perception. Little research has assessed receipt of health advice from a provider among women with preeclampsia and its association with risk perception regarding future risk of high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Among women with recent diagnoses of preeclampsia or gestational diabetes, we assessed associations between receipt of health advice from providers, psychosocial factors, and type of pregnancy complication with risk perception for future chronic illness.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional analysis among 79 women diagnosed with preeclampsia and/or gestational diabetes using surveys and medical record abstraction after delivery and at 3 months postpartum.

Results: Overall, fewer than half of the 79 women with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes reported receiving health advice from a provider, and women with preeclampsia were significantly less likely to receive counseling as compared with women with gestational diabetes (odds ratio 0.23). We did not identify a difference in the degree of risk perception by pregnancy complication or receipt of health advice. There were no significant differences in risk perception based on age, race, education, or health insurance coverage.

Conclusions: We demonstrated that women with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes are not routinely receiving health advice from providers regarding future chronic disease risk, and that women with preeclampsia are less likely to be counseled on their risk, compared with women with gestational diabetes. Provider and patient-centered interventions are needed to improve postpartum care and counseling for women at high risk for chronic disease based on recent pregnancy complications.

Keywords: preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, provider counseling, risk perception, future chronic disease risk, postpartum

Introduction

Women who are diagnosed with gestational diabetes or preeclampsia while pregnant have an elevated risk for future type-2 diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease compared with women without these pregnancy complications.1–3

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, including 20 studies, women with gestational diabetes had a significantly increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared with women with a normoglycemic pregnancy (relative risk 7.43).2 Similarly, in another systematic review and meta-analysis, the relative risk of developing hypertension and ischemic heart disease later in life after a pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia were 3.70 and 2.16, respectively.4 In fact, the American Diabetes Association has recognized gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) as a significant risk factor for type 2 diabetes, and the American Heart Association has recognized preeclampsia as a cardiovascular disease risk factor in their 2011 and 2018 guidelines.5–7

The pregnancy and the postpartum period is a critical but often missed opportunity for health intervention. During pregnancy, women engage with the health care system in a predictable way, allowing for health intervention, counseling, and behavior change. Since women with gestational diabetes are likely to have impaired glucose tolerance in the future, the postpartum period is an ideal screening period and would allow for early interventions, such as lifestyle modification and metformin administration, which have been demonstrated in the Diabetes Prevention Program Study to prevent type 2 diabetes.8,9 While studies have investigated rates of glucose testing in the postpartum period, there are no studies that quantify rates of counseling regarding future diabetes risk in women with histories of gestational diabetes.

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommendations on the postpartum period recommend counseling women with history of preeclampsia about future risk of cardiovascular disease and screening women with the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease risk assessment tool.1 However, a survey of providers in 2012 showed that only 9% of internists and 38% of obstetrician/gynecologists provided cardiovascular risk reduction counseling to women with preeclampsia and had overall limited knowledge of the associated risk.

Provider knowledge has been increasing, with a 2015 study showing that 73% of obstetrician/gynecologists and 55% of internists identifying preeclampsia history as important for cardiovascular risk assessment.10,11 However, to our knowledge, no studies have examined how many women with preeclampsia report receiving the recommended counseling or how this influences patient perception of their own risk.

Risk perception, defined as perceived susceptibility or feelings of personal vulnerability to a condition, has been demonstrated to affect health behaviors and therefore may be a critical tool for postpartum risk counseling. Overall, risk perception has been shown to be associated with the adoption of certain health behaviors, including lifestyle modification.12 However, heightened risk perception can also be associated with psychological stress and depression as seen in women with high-risk perception for breast and ovarian cancer.13

Previous research has shown that women with gestational diabetes do not perceive the risk between gestational diabetes and future diabetes, potentially reducing their likelihood of making long-term behavior changes postpartum14 While the perception of risk has increased with improved understanding of gestational diabetes as a risk factor for future diabetes, the disparity between knowledge and risk perception persists. A 2016 patient survey demonstrated that 50% of patients perceive themselves as low risk, despite 89% of patients acknowledging gestational diabetes as a risk factor.15

Among women with preeclampsia, fewer studies addressed the patients' understanding of preeclampsia as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease or how this affects risk perception. A focus group study demonstrated that few women perceived the relationship between preeclampsia and future cardiovascular disease risk.16 Further research is required to understand the extent to which women with preeclampsia perceive risk of future cardiovascular disease, or what factors influence risk perception in these populations. In addition, while providers have an important role in communicating future risk, no studies have examined the association of risk perception with report of receiving health advice from a provider.

In this study, we assessed the associations between the pregnancy complications, gestational diabetes, and preeclampsia, and receipt of health advice by a provider, risk perception, and health care utilization. We hypothesized that women with preeclampsia would be less likely to receive health advice from a provider regarding their future chronic disease risk and would therefore have lower risk perception as compared with those with gestational diabetes. We also examined demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical predictors of risk perception between women with a history of a pregnancy complication who perceived themselves as high or low risk.

Methods

This study was approved by The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine IRB.

Study design, population, and setting

This study was part of a larger 12-month prospective cohort study aimed at evaluating postdelivery health care utilization and health behaviors among women with preeclampsia and/or gestational diabetes mellitus. Additional eligibility for the cohort study were: Age 18 years old or older, Spanish or English speaking. Recruitment for the main cohort occurred between October 2013 and May 2015 from three hospitals in the Baltimore, MD region. All women with preeclampsia were recruited from one of the inpatient postpartum units following delivery. Women with gestational diabetes were recruited either from the postpartum unit or from the obstetrical ultrasound unit during their last prenatal surveillance ultrasound before delivery. Screening for eligibility occurred before approaching the patient about the study; all women deemed eligible were consented and enrolled.

For this study, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis among 79 of the 134 participants who completed both a baseline and 3 months follow-up phone interview surveys. There was a 58% response rate for the 3-month survey. We also excluded 4 participants who had both preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, leaving a total sample of 79 (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Data collection

In-person surveys were interviewer administered at the time of recruitment while on the postpartum floor within 1–2 days of delivery (baseline). Three-month postpartum follow-up surveys were performed by trained interviewers by telephone. We performed medical record abstraction to identify preeclampsia and gestational diabetes diagnoses either in the current problem list at the time of recruitment or in their discharge summary at the time of delivery. Diagnosis was verified by medical provider review using standard diagnostic criteria (W.L.B., D.N., J.H.).17,18

Data collection as part of the baseline survey

Sociodemographic and family structure questions were adapted from existing standard surveys in pregnancy.19,20 Prenatal physical activity was assessed postpartum and reported as the sum of the number of times per week a woman performed strenuous, moderate, or mild physical activity, each multiplied by the metabolic equivalent of task (hours per week).21 Prenatal diet was assessed as sugary beverage consumption and fast food consumption with questions from the CDC addressing the frequency of consumption of fruit juice, fruit drinks, soda, and energy drinks throughout pregnancy.22 Fast food intake was assessed using the question, “How often did you eat fast food?” with responses ranging from “never” to “2 or more times per day.”23

Data collection as part of the 3-month survey

We assessed risk perception using five questions from the “Your Health” section of the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Core Set of Measures of Functioning and Well Being, a standard quality of life assessment tool.24 We chose this instrument because it assesses risk perception and has been validated in several populations, particularly patients with chronic health conditions.25,26 We then added two additional questions specific to women's perceived risk about the baby's health. These seven questions are included in Table 2. Risk perception was scored using the method described in the manual.24 Women were considered to have high-risk perception if their mean score was >30, based on the population median. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the risk perception survey questions was 0.65.

Table 2.

Individuals Risk Perception Question Responses by Pregnancy Complication

| Question | GDM (n = 46) | Preeclampsia (n = 33) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| I seem to get sick a little easier than other women (agree),an (%) | 3 (6.5) | 3 (9.1) | 0.67 |

| I am as healthy as anyone I know (n disagree),bn (%) | 9 (19.5) | 6 (18.2) | 0.88 |

| I expect my health to get worse (agree), n (%) | 6 (13.0) | 3 (9.1) | 0.59 |

| My health is excellent (disagree), n (%) | 14 (30.4) | 6 (18.2) | 0.22 |

| I worry about my health (agree), n (%) | 26 (56.5) | 13 (39.4) | 0.13 |

| My baby's health is excellent (disagree), n (%) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.39 |

| I worry about my baby's health (agree), n (%) | 22 (47.8) | 11 (33.3) | 0.20 |

Agree indicated as 4 or 5 on Likert scale.

Disagree indicated as 1 or 2 on Likert scale.

“Receipt of health advice by a provider” as part of the 3-month telephone survey using two questions: “In the last 3 months did a doctor say that you could develop diabetes?” and “In the last 3 months did a doctor say you could develop high blood pressure?”27 Women diagnosed with gestational diabetes were considered advised of their risk if a doctor said they could develop diabetes, and women with preeclampsia were considered advised of their risk if the doctor said they could develop high blood pressure.

Postpartum depression was assessed at 3 months postpartum using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and scored according to Cox et al.28 Women with a score of 9 or greater were considered to be at high risk for having postpartum depression, as recommended by Cox et al. for clinical settings.28

Statistical analyses

We assessed differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between women with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes using the Student's t-test and the chi square goodness-of-fit test. We used logistic regression to model the association between preeclampsia or gestational diabetes diagnosis and risk perception, health care utilization, advice from a provider adjusting for age, marital status, education, employment, insurance, and parity. All analyses were performed using STATA version 14.2.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 79 women who completed 3 months follow-up telephone surveys, by diagnosis of gestational diabetes (58.2%) or preeclampsia (41.8%). Mean age was 30.9 (standard deviation [SD] 0.68) and mean prepregnancy body mass index was 32.5 kg/m2 (SD 1.2). Around 41.8% were Black, 40.5% were White, 8.9% were of Hispanic ethnicity, and 77.2% completed at least some college.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics, Including Demographic Characteristics, Prenatal Physical Activity, and Diet, as Well as Risk Perception and Health Advice Received at 3 Months Postpartum

| Variable | Total (n = 79), mean (SD) or n (%) | Preeclampsia (n = 33), mean (SD) or n (%) | Gestational diabetes (n = 46), mean (SD) or n (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, SD) | 30.9 (0.68) | 28.6 (1.1) | 32.6 (0.8) | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2, SD) | 32.5 (1.2) | 34.1 (2.0) | 31.7 (1.6) | 0.34 |

| Married, n (%) | 40 (50.6) | 14 (42.4) | 26 (56.5) | 0.34 |

| Employed full or part time, n (%) | 67 (84.8) | 27 (81.8) | 40 (87.0) | 0.53 |

| Hispanic ethnicity, n (%) | 7 (8.9) | 3 (9.1) | 6 (13.0) | 0.59 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 32 (40.5) | 11 (33.3) | 21 (45.7) | 0.11 |

| Black | 33 (41.8) | 19 (57.6) | 14 (30.4) | |

| Other racesa | 14 (17.7) | 3 (9.1) | 11 (23.9) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| GED or less | 18 (22.8) | 8 (24.2) | 10 (21.7) | 0.57 |

| Any college | 26 (32.9) | 12 (36.4) | 14 (30.4) | |

| Graduated college | 35 (44.3) | 13 (39.4) | 22 (47.8) | |

| Health insurance, n (%) | ||||

| Medicaid | 25 (31.6) | 16 (48.5) | 9 (19.6) | 0.03 |

| Commercial | 47 (59.5) | 14 (42.4) | 33 (71.7) | |

| No insurance or not known | 7 (8.9) | 3 (9.1) | 4 (8.7) | |

| Parity, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 33 (41.8) | 19 (57.6) | 14 (30.4) | 0.05 |

| 2 | 29 (36.7) | 9 (27.3) | 20 (43.5) | |

| >2 | 17 (21.5) | 5 (15.2) | 12 (26.1) | |

| Prenatal health behaviors | ||||

| Physical activity in MET hours per week (mean, SD) | 9.4 (9.8) | 9.0 (12.4) | 9.4 (6.6) | 0.88 |

| Total sugary drinks per day, n (%) | ||||

| <1 | 11 (13.9) | 1 (3.0) | 10 (21.7) | 0.01 |

| 1–2 | 52 (65.8) | 21 (63.6) | 31 (67.4) | |

| >2 | 13 (16.5) | 11 (33.3) | 5 (10.9) | |

| Fast food consumed weekly, n (%) | ||||

| <1 | 33 (41.8) | 11 (33.3) | 22 (47.8) | 0.37 |

| 1 | 25 (31.6) | 11 (33.3) | 14 (30.4) | |

| >1 | 21 (26.6) | 11 (33.3) | 10 (21.7) | |

| Past medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Chronic hypertension | 14 (17.7) | 8 (24.2) | 6 (13.0) | 0.20 |

| Prior preeclampsia | 8 (10.1) | 4 (12.1) | 4 (8.7) | 0.62 |

| Prior GDMb | 11 (13.9) | 9 (27.3) | 2 (4.3) | 0.09 |

| Risk perception | ||||

| Risk Perception scale (median, IQR) | 28.6 (25) | 25 (28.6) | 28.6 (28.6) | 0.30 |

| High perceived risk (≥30), n (%) | 33 (41.8) | 12 (36.4) | 21 (45.7) | 0.37 |

| Advised of risk of future chronic disease by provider,cn (%) | 29 (36.7) | 8 (24.2) | 21 (45.7) | 0.05 |

| Health care utilization | ||||

| Attended a postpartum visit within 3 months | 75 (94.9) | 31 (93.9) | 44 (95.7) | 0.73 |

| Emergency room visit in 3 months | 8 (10.1) | 3 (9.1) | 5 (10.9) | 0.80 |

Other races include Asian, mixed race, and other.

No patients were previously diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Advised of risk of diabetes for women with gestational diabetes or high blood pressure for women with preeclampsia.

BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; IQR, interquartile range; MET, metabolic equivalent of task; SD, standard deviation.

Women with preeclampsia were younger (mean age 28.6 vs. 32.6, p < 0.01), more likely to be nulliparous (57.6% vs. 30.4%, p = 0.05), Black (57.6% vs. 30.4%, p = 0.11), and have Medicaid insurance (48.5% vs. 9.6%, p = 0.03) compared with women with gestational diabetes. The majority of women reported attending a postpartum health care visit by 3 months (93.9% and 95.7% for women with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the number of women who presented to the emergency department during this time period (9.1% and 10.9% of those with preeclampsia preeclampsia and GDM, respectively) (Table 1).

We noted no differences in physical activity or fast food intake in pregnancy between women with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, but women with preeclampsia were more likely to drink one or more sugary drinks per day during their pregnancy as compared with women with gestational diabetes (97.0% vs. 78.2%, p < 0.01). Women with preeclampsia were significantly less likely to report receipt of health advice from their provider regarding their future chronic disease risk as compared with women with gestational diabetes (24.2% vs. 45.7%, p = 0.02).

Nineteen of the 79 women had a history of gestational diabetes or preeclampsia before the index pregnancy. Additionally, 14 of the women, 8 of those with superimposed preeclampsia and 6 with gestational diabetes, had diagnoses of chronic hypertension.

Compared with the overall sample of 134 women, the 79 women in this analysis were more likely to have graduated college (44.3% vs. 35.1%) and to have Medicaid insurance (31.7% vs. 11.9%).

Association between pregnancy complication and receipt of health advice by a provider, high perceived risk, and health care utilization

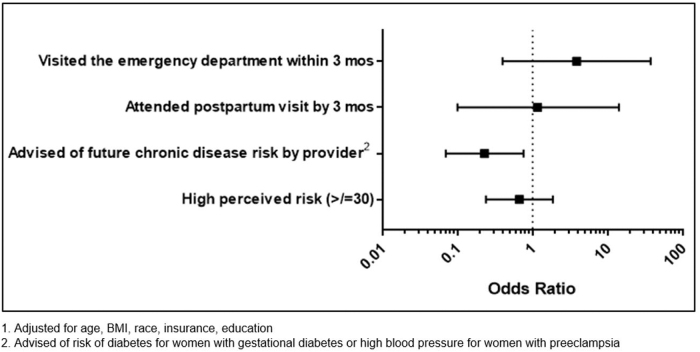

Women with preeclampsia were significantly less likely to receive health advice from their provider regarding their future chronic disease risk as compared with women with gestational diabetes (24.2% vs. 45.7%, p = 0.02). There was no statistically significant association between pregnancy complication and the proportion of women with high-risk perception (36.4% and 45.7%, p = 0.44) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Association between preeclampsia (vs. gestational diabetes [ = Ref.]1) and utilization of care, receipt of health advice, and risk perception for chronic disease.

The majority of women with histories of preeclampsia or gestational diabetes attended a postpartum visit by 3 months (93.9% and 95.7%, respectively). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the number of women who presented to the emergency department during this time period (9.1% and 10.9% of those with preeclampsia and GDM, respectively (Fig. 1).

Association between risk perception and pregnancy complication

The proportion of women with high risk perception (average score ≥30 on a scale of 0–100) was not significantly different in women with preeclampsia as compared with women with gestational diabetes. In an itemized analysis of the risk score, there were no significant difference in the number of women who agreed or disagreed with each statement based on pregnancy complication. Overall, women with preeclampsia were less likely to expect their health to get worse (9% vs. 13%), to worry about their health (39% vs. 57%), and to worry about their baby's health (33% vs. 48%) as compared with women with gestational diabetes and were more likely to agree that they are healthy and that their and their baby's heath are excellent. However, these results were nonsignificant (Table 2).

Of the 19 women with history of gestational diabetes or preeclampsia before the index pregnancy, 8 (42%) had high-risk perception. This was similar to the overall proportion of women with high perceived risk (41.8%). The median and interquartile range of risk perception scores were also similar in those with prior history of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia as compared with the general study population (28.6 [16.1] compared with 28.6 [16.5], respectively).

Associations between risk perception and health advice, postpartum depression

We noted no statistically significant association between receipt of health advice and perceived risk of future disease (health advice received in 35.6 and 39.4% of those with low- and high-risk perception, respectively, p = 0.57) (Supplementary Table S1).

High-risk perception was associated with 10-fold increased odds of scoring a 9 or greater on EPDS. In those with a high-risk score (≥30), 30.3% of women were at risk for postpartum depression based on the EPDS, compared with 4.4% of those in the low-risk group (odds ratio 20.5, Supplementary Table S1). This difference was also seen when the population was separated by complication (data not shown). In the four women with preeclampsia who were at risk for postpartum depression, three of them had high-risk perception scores. Seven of the eight women with gestational diabetes who were at high risk of postpartum depression had high-risk perception scores.

We did not detect any significant differences in risk perception between women by age, race, insurance type, and education level, both in the total population and when stratified by pregnancy complication. Additionally, there were no significant differences in risk perception between women who did and did not receive health advice from their provider regarding their future chronic disease risk. Since 8 of the women who reported a history of preeclampsia had already developed chronic hypertension (i.e., were not at risk for hypertension) and, as such, may not have received related counseling from their provider, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding these women and the conclusions were unchanged.

Discussion

In a sample of 79 women with recent preeclampsia or gestational diabetes, we had predicted that women with preeclampsia would have lower risk perception for future chronic disease and also be less likely to receive health advice from a provider regarding their future chronic disease risk. We found that women with preeclampsia were 23% less likely to receive health advice from their provider regarding future chronic disease risk as compared with women with gestational diabetes, but rates of risk perception were similar and low between the two groups. Overall, the receipt of health advice was low among both groups with only 45.7% of women with gestational diabetes and 24.2% of women with preeclampsia receiving health advice from a provider. We also predicted that the lack of health advice would be associated with lower levels of risk perception among women with preeclampsia as compared with those with gestational diabetes. However, we did not find a statistically significant difference in risk perception between these groups. Both women with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes had relatively low levels of risk perception.

While prior research found low-risk perception for future chronic illness among women with gestational diabetes, less was known about risk perception among women with preeclampsia, as well as the role of health advice from providers and other potential factors that influence risk perception in these populations. Previous studies have found that internists and obstetrician/gynecologists were less aware of the relationship between preeclampsia and future ischemic heart disease risk than they were between gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes risk.14,29 Additionally, in prior studies, providers reported low rates of counseling their patients with history of preeclampsia regarding their future chronic disease risk.10,11

Our study also showed that women with preeclampsia were less likely to receive health advice as compared with women with gestational diabetes. While few previous studies described the content and frequency of provider counseling in peripartum care, particularly for patients with pregnancy complications, studies that have been performed in general pregnant populations demonstrate low rates of counseling. In a study of audio recordings of prenatal visits, weight-related behavior counseling in pregnancy was overall low for patients in the general pregnant population.30 In addition, in a national survey, rates of self-reported postpartum counseling for breastfeeding were low indicating that the peripartum period is often a missed opportunity for health advise and counseling.31

Regarding risk perception, we found relatively low-risk perception for future chronic disease, with only 41.8% of women having high-risk perception, and no significant difference between women who had gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. The low rates of perceived risk are especially concerning, since older research by Kim et al. showed low-risk perception, despite high knowledge of the association between gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes.14 In fact, studies characterizing risk perception in nonpregnant women regarding heart disease risk and diabetes risk also showed low rates of risk perception, indicating that gaps in risk perception may be attributable to a larger societal understanding of the risk factors for these chronic conditions.32,33

Further research into this disconnect between counseling and risk perceptions should aim to clarify what information is communicated in postpartum visits and how, as well as whether or not counseling leads to improved patient knowledge and motivates behavior change to prevent chronic disease.

Finally, in our analysis to identify factors affecting risk perception, we found no significant association between risk perception and receipt of health advice. Additionally, there were no significant associations between risk perception, age, race, insurance coverage, or education level. We did find an association between postpartum depression and high-risk perception, although the directionality of this relationship is unclear. This is consistent with past literature that demonstrated a correlation between high-risk perception and depression in individuals with lung cancer.34 While previous research has demonstrated the role of risk perception in modifying future health behaviors, the relationship between mental health and risk perception and the potential negative consequences of high-risk perception need to be considered.

While our study did not show an association between receipt of provider counseling and risk perception, intervention studies continue to use education about future risk as a tool to motivate future health behavior and mitigate the risk of future chronic disease. Interventions such as the Diabetes Prevention Program, which included women with gestational diabetes because of their diabetes risk, showed that intensive lifestyle modification and counseling reduced the incidence of type 2 diabetes in women with a history of gestational diabetes by ∼50%.35

Use of more than 1 of the 5A's in the 5 A's (ask, assess, advise, agree, and assist) behavior change counseling strategy was associated with decreased weight gain.36 The 5 As counseling method is also shown to be effective in prenatal smoking cessation and has been integrated into the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology clinical recommendations.37 Importantly, a recent randomized control trial among 151 women with a recent history of preeclampsia of a remotely delivered lifestyle coaching intervention demonstrated significant improvements in knowledge of cardiovascular disease risk factors and self-efficacy related to healthy eating as well as decreased physical inactivity.38

The low rates of health counseling and advice that we observed in our study indicate that there is room for improvement. The first year after a delivery is a critical window for promoting long-term health in women with pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia and gestational diabetes since the increased risk of cardiovascular disease is observed starting within 1 year postpartum.39 Using clinically supported behavioral modification and motivation strategies to discuss future cardiovascular and metabolic disease risk and to encourage lifestyle interventions is an important future step for mitigating the risk. In the Balance After Baby program, web-based lifestyle programs assigned to women with history of gestational diabetes can improve postpartum health outcomes, including postpartum weight retention.40

Future research on interventions that utilize these methods to improve provider counseling will help elucidate the relationship among counseling, risk perception, and future behavior change. In addition to it being an important time for counseling regarding future chronic disease risk, the postpartum visit is also a critical time for screening tests, including the oral glucose tolerance test and blood pressure screening.

There are several notable limitations of this study. First, this study has a small sample size and because risk perception was assessed 3 months after delivery, we had significant participant dropout. Participants that dropped out were more likely to have reached an education level of GED or less and were more likely to have commercial insurance. Otherwise there were no significant differences in the original cohort and participating population at 3 months.

Second, the risk perception instrument was not specific for the development of type 2 diabetes, or hypertension and cardiovascular disease. More specific questions about risks could have elucidated differences in risk perception between women with gestational diabetes and preeclampsia and women who did or did not receive health advice, which we did not show.

Third, while we assessed provider counseling regarding the most proximal and most likely health risks for those with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes (hypertension and type 2 diabetes, respectively),41,42 we acknowledge that both of these groups of women are also at risk for cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, if a woman with preeclampsia was counseled about her risk of developing diabetes but not hypertension, our analytic approach did not consider her to have received health advice from a provider (despite the fact that she also has an increased risk of type 2 diabetes).

Fourth, this study was designed to evaluate follow-up care for women with gestational diabetes and preeclampsia and therefore did not include a normal pregnancy comparison group. However, previous studies have characterized health care utilization in individuals with normal pregnancies as compared with those with pregnancy complications.43

Fifth, we showed a relationship between postpartum depression and risk perception, but because few women had postpartum depression, this finding will need to be confirmed with future studies.

Conclusions

Given the well-established relationship between pregnancy complications and future risk of chronic disease, it is important to understand the contributing and ameliorating factors of this progression. This study theorized that health advice and risk perception would differ among those with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes. Despite greater evidence and public campaigning about risk of future chronic disease in these populations, provider counseling remained low in women with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, but lower for women with preeclampsia. While health advice differed significantly between these groups, health advise was not associated with differences in risk perception. Risk perception was most significantly correlated to receiving a high score on the EPDS, indicating a significant relationship between risk perception and mental health postpartum.

Practice implications

Overall, this study demonstrated that we need improved provider-based counseling of future chronic disease risk, especially among women with preeclampsia. Future studies are needed to better understand contributing factors to accurate risk perception among women with these pregnancy complications, specifically related to their risk of developing chronic disease. Additionally, more research on ways to modify risk perception in these populations would allow providers to more effectively target risk perception to improve health behaviors and outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This project was funded by a Career Development Award from National Institute of Health-National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (K23HL098476). This funding source had no involvement in study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Optimizing postpartum care. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:140–150 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bellamy L, Casas J-P, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:1773–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Craici I, Wagner S, Garovic VD. Preeclampsia and future cardiovascular risk: Formal risk factor or failed stress test? Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 2008;2:249–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bellamy L, Casas J-P, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med J 2007;335:974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. 13. Management of diabetes in pregnancy: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care 2018;41:S137–S143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women—2011 Update. Circulation 2011;123:1243–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018;71:1269–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shah BR, Lipscombe LL, Feig DS, Lowe JM. Missed opportunities for type 2 diabetes testing following gestational diabetes: A population-based cohort study. BJOG 2011;118:1484–1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Keely E. An opportunity not to be missed—How do we improve postpartum screening rates for women with gestational diabetes? Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2012;28:312–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wilkins-Haug L, Celi A, Thomas A, Frolkis J, Seely EW. Recognition by women's health care providers of long-term cardiovascular disease risk after preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:1287–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Young B, Hacker MR, Rana S. Physicians' knowledge of future vascular disease in women with preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy 2012;31:50–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol 2007;26:136–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cicero G, De Luca R, Dorangricchia P, et al. Risk Perception and psychological distress in genetic counselling for hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer. J Genet Couns 2017;26:999–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim C, McEwen LN, Piette JD, Goewey J, Ferrara A, Walker EA. Risk perception for diabetes among women with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2281–2286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mukerji G, Kainth S, Pendrith C, et al. Predictors of low diabetes risk perception in a multi-ethnic cohort of women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 2016;33:1437–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Skurnik G, Roche AT, Stuart JJ, et al. Improving the postpartum care of women with a recent history of preeclampsia: A focus group study. Hypertens Pregnancy 2016;35:371–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:e1–e25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gestational diabetes mellitus. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e49–e64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/ Accessed July23, 2019

- 20. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/prams/ Accessed July23, 2019

- 21. Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci 1985;10:141–146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2013. Available at: www.cdc.gov/brfss Accessed July23, 2019

- 23. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Year 25. Diet practices (form 48), May 2015. Available at: www.cardia.dopm.uab.edu Accessed July23, 2019

- 24. Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel R. User's manual for the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) core measures of health-related quality of life. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bozzette SA, Hays RD, Berry SH, Kanouse DE. A Perceived Health Index for use in persons with advanced HIV disease: Derivation, reliability, and validity. Med Care 1994;32:716–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989;262:907–913 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nichols GA, Desai J, Elston Lafata J, et al. Construction of a multisite DataLink using electronic health records for the identification, surveillance, prevention, and management of diabetes mellitus: The SUPREME-DM project. Prev Chronic Dis 2012;9:E110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gabbe SG, Gregory RP, Power ML, Williams SB, Schulkin J. Management of diabetes mellitus by obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:1229–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Washington Cole KO, Roter DL. Starting the conversation: Patient initiation of weight-related behavioral counseling during pregnancy. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:1603–1610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jarlenski M, McManus J, Diener-West M, Schwarz EB, Yeung E, Bennett WL. Association between support from a health professional and breastfeeding knowledge and practices among obese women: Evidence from the Infant Practices Study II. Womens Health Issues 2014;24:641–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mosca L, Jones WK, King KB, Ouyang P, Redberg RF, Hill MN. Awareness, perception, and knowledge of heart disease risk and prevention among women in the United States. American Heart Association Women's Heart Disease and Stroke Campaign Task Force. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:506–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Walker EA, Caban A, Schechter CB, et al. Measuring comparative risk perceptions in an urban minority population: The risk perception survey for diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2007;33:103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Floyd AHL, Westmaas JL, Targhetta V, Moyer A. Depressive symptoms and smokers' perceptions of lung cancer risk: Moderating effects of tobacco dependence. Addict Behav 2009;34:154–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ratner RE, Christophi CA, Metzger BE, et al. Prevention of diabetes in women with a history of gestational diabetes: Effects of metformin and lifestyle interventions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:4774–4779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Washington Cole KO, Gudzune KA, Bleich SN, et al. Influence of the 5A's counseling strategy on weight gain during pregnancy: An observational study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017;26:1123–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smoking cessation during pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 721. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:200–204 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rich-Edwards JW, Stuart JJ, Skurnik G, et al. Randomized trial to reduce cardiovascular risk in women with recent preeclampsia. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2019;28:1493–1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ehrenthal DB, Maiden K, Rogers S, Ball A. Postpartum healthcare after gestational diabetes and hypertension. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23:760–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nicklas JM, Zera CA, England LJ, et al. A web-based lifestyle intervention for women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:563–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Catov JM. Pregnancy as a window to cardiovascular disease risk: How will we know? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:691–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim C. Maternal outcomes and follow-up after gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 2014;31:292–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bennett WL, Chang H-Y, Levine DM, et al. Utilization of primary and obstetric care after medically complicated pregnancies: An analysis of medical claims data. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:636–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.