Abstract

Strains MS586T and MS82, which are aerobic, Gram‐negative, rod‐shaped, and polar‐flagellated bacteria, were isolated from the soybean rhizosphere in Mississippi. Taxonomic positions of MS586T and MS82 were determined using a polyphasic approach. 16S rRNA gene sequence analyses of the two strains showed high pairwise sequence similarities (>98%) to some Pseudomonas species. Analysis of the concatenated 16S rRNA, rpoB, rpoD, and gyrB gene sequences indicated that the strains belonging to the Pseudomonas koreensis subgroup (SG) shared the highest similarity with Pseudomonas kribbensis strain 46‐2T. Analyses of average nucleotide identity (ANI), genome‐to‐genome distance, delineated MS586T and MS82 from other species within the genus Pseudomonas. The predominant quinone system of the strain was ubiquinone 9 (Q‐9), and the DNA G+C content was 60.48 mol%. The major fatty acids were C16:0, C17:0 cyclo, and the summed features 3 and 8 consisting of C16:1ω7c/C16:1ω6c and C18:1ω7c/C18:1ω6c, respectively. The major polar lipids were phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylethanolamine, and diphosphatidylglycerol. Based on these data, it is proposed that strains MS586T and MS82 represent a novel species within the genus Pseudomonas. The proposed name for the new species is Pseudomonas glycinae, and the type strain is MS586T (accession NRRL B‐65441 = accession LMG 30275).

Keywords: average nucleotide identity, Pseudomonas glycinae, rhizosphere, soybean

Bacterial strains MS586T and MS82 were isolated from soybean rhizosphere in Mississippi. Both strains exhibited striking antimicrobial activity. According to analyses of phylogenetic, phenotypic, physiological, biochemical, and chemotaxonomic characteristics, strains MS586T and MS82 represent a novel species of the genus Pseudomonas, which belongs to the Pseudomonas koreensis subgroup. The proposed name for the new species is Pseudomonas glycinae, and the type strain is MS586T.

1. INTRODUCTION

The genus Pseudomonas was first described by Migula (1894). Strains of this genus have been found in natural habitats including plants, soil, animals, and water (Palleroni, 1994). Members of the genus Pseudomonas are known to be Gram‐negative, rod‐shaped, cream‐colored, and polar‐flagellated. Pseudomonas spp. have great metabolic and nutritional versatility. Some strains of Pseudomonas spp. play potential roles as bioremediation agents to alleviate various hazardous organic substrates, such as sodium dodecyl sulfate (Furmanczyk, Kaminski, Lipinski, Dziembowski, & Sobczak, 2018). Some strains of Pseudomonas spp. promote plant growth directly by facilitating resource acquisition or indirectly by decreasing the inhibitory effects of various pathogenic agents on plant growth and development; however, some other strains of Pseudomonas can act as pathogens inciting plant diseases (Moore et al., 1996; Oueslati et al., 2019; Ye et al., 2019).

Over 200 species of Pseudomonas are included in the Bacterial Names with Standing in Nomenclature (http://www.bacterio.net). Numerous methods, including physiological, molecular, and phenotypic distinctions (Sneath, Stevens, & Sackin, 1981); 16S rDNA gene sequencing; and multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) (Pascual, Macián, Arahal, Garay, & Pujalte, 2010), have been used to identify the taxonomic status of Pseudomonas species. With the accumulation of genomic data, the analysis of complete genomes is very useful in Pseudomonas taxonomy (Hesse et al., 2018; Peix, Ramirez‐Bahena, & Velazquez, 2018). Average nucleotide identity (ANI) values calculated from genome assemblies have been widely used for the taxonomy of bacteria (Konstantinidis & Tiedje, 2005). ANI evaluates a large number of nucleic acid sequences, including some that evolve quickly and others that evolve slowly, in its calculation and reduces the influence of horizontal gene transfer events or variable evolutionary rates. It has been suggested that species descriptions of bacteria and archaea should include a high‐quality genome sequence of at least the type strain as an obligatory requirement (Rosselló‐Móra & Amann, 2015). The current metagenome databases have shown evidence for approximately 8000 sequence‐discrete natural populations, which is roughly equivalent to species at the 95% ANI level (Rosselló‐Móra & Whitman, 2018). Genome‐to‐genome distance (GGDC 2.0) is another highly effective method for inferring whole‐genome distances. GGDC effectively mimics DNA‐DNA hybridization for genome‐based species delineation and subspecies delineation (Meier‐Kolthoff, Auch, Klenk, & Göker, 2013). Therefore, ANI and GGDC are highly effective ways to evaluate the genetic relatedness between genomes. Strains MS586T and MS82 were isolated from the rhizosphere soybean plants growing in fields where most plants were infected by the charcoal rot pathogen Macrophomina phaseolina. Plate bioassay indicated both strains MS586T and MS82 exhibited striking antimicrobial activity (Ma et al., 2017). This research is focused on the characterization of the taxonomic position of the two strains.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Bacterial strains and growth conditions

MS586T and MS82 were isolated from a soybean rhizosphere sample by standard dilution plating on nutrient broth yeast extract (NBY) agar medium (Vidaver, 1967) at 28°C. Antimicrobial activity against multiple plant pathogens was detected with an antifungal plate assay as previously described (Gu, Wang, Chaney, Smith, & Lu, 2009). Following purification, the bacterium was preserved in 20% glycerol at −80°C. Pseudomonas spp. type strains and reference strains were provided by the Leibniz Institute DSMZ—German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). All strains used in this study are summarized in Table A1.

2.2. Cell morphology and physiological tests

Colony morphology of the strains MS586T and MS82 was determined after growth on NBY agar plates. Gram staining was performed as described previously (Murray, Doetsch, & Robinow, 1994); cell morphology and flagellation types were observed with a transmission electron microscope (TEM) using routine negative glutaraldehyde staining; and the production of fluorescent pigments was tested on King B medium (King, Ward, & Raney, 1954). Optical density (OD600) metrics recorded for NBY liquid cultures were used to evaluate optimal growth and pH, at temperatures from 4°C to 40°C, with an interval of 4°C for 24 hr, and at pH 4.0–10.0.

Physiological and biochemical tests were conducted as described previously (Peix, Berge, Rivas, Abril, & Velázquez, 2005). Cellular fatty acids were identified using the Sherlock 6.1 system (Microbial IDentification Inc.) and the library RTSBA6 (Sasser, 1990). Biochemical features and enzyme activities were determined using API 20 NE and API 50 CH strips with API 50 CHB/E medium (bioMerieux), as well as Biology GENIII Microplates (Biolog) as directed in the manufacturer's instructions; results were recorded after incubation for 48 hr at 28°C.

2.3. Phylogenetic analysis

Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) protocol (Doyle, 1987) and used as a template to amplify the nearly full‐length 16S rRNA gene. PCR was performed with the 16S rRNA universal primers 27F (5′‐AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG‐3′) and 1492R (5′‐TACGGHTACCTTGTTACGACTT‐3′) (Chelius & Triplett, 2000; Lane, 1991). Amplification and partial sequencing of rpoB (Tayeb, Ageron, Grimont, & Grimont, 2005), rpoD (Mulet, Bennasar, Lalucat, & García‐Valdés, 2009), and gyrB (Yamamoto et al., 2000) housekeeping genes were performed following previously described methods (Mulet et al., 2009) using primers LAPS (5′‐TGGCCGAGAACCAGTTCCGCGT‐3′)/LAPS27 (5′‐CGGCTTCGTCCAGCTTGTTCAG‐3′) for ropB, PsEG30F (5′‐ATYGAAATCGCCAARCG‐3′)/PsEG790R (5′‐CGGTTGATKTCCTTGA‐3′) for rpoD, and APrU (5′‐TGTAAACGACGGCCAGTGCNGGRTCYTTYTCYTGRCA‐3′)/UP1E (5′‐CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCAYGSNGGNGGNAARTTYRA‐3) for gyrB. All PCR was performed with a PTC‐200 Peltier Thermal Cycler (MJ Research), and products were purified using a Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean‐Up System (Promega). Sanger sequencing reactions were performed using the Eurofins MWG Operon.

Phylogenetic analysis of the multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) was performed in MEGA 7 software using the maximum‐likelihood algorithm (Kumar, Stecher, & Tamura, 2016). The sequence fragments of the four genes (16s rRNA, rpoB, rpoD, and gyrB) were concatenated in the following order: 16s rRNA, rpoB, rpoD, and gyrB. Sequences of type strains used in the MLSA were downloaded from NCBI (accession numbers in Table A2). The maximum‐likelihood method was used to construct the phylogenetic tree with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

2.4. DNA fingerprinting

DNA fingerprinting has been evaluated and proposed as a reliable method for distinguishing different strains in the same taxon, which are not clonal varieties. Thus, the primer sequence corresponding to BOX elements (BoxA1R: 5′‐CTACGGCAAGGCGACGCTGACG‐3′) was used for DNA fingerprinting (Koeuth, Versalovic, & Lupski, 1995). PCR amplification was conducted as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles (94°C for 1 min, 52°C or 53°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min), and finally 72°C for 8 min. The DNA fragments were analyzed in a 2% agarose gel.

2.5. Genome sequencing and analysis

Genomic DNA of strain MS586T was extracted using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega Corporation). The extracted genomic DNA was used for library construction with an average insert size of 400 bp, and three mate‐pair libraries with an average insert size of 2000 bp, 5000 bp, and 8000 bp were prepared and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq instrument according to the manufacturer's instructions (Illumina). The standard library and 2000‐bp mate‐pair library were selected for de novo assembly using a method described by Durfee et al. (2008) using DNASTAR Lasergene software (DNASTAR, Inc.). The genome was annotated using the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (Angiuoli et al., 2008). The complete genome sequence was deposited in GenBank under accession number CP014205, and the genome project was deposited in the Genomes OnLine Database under GP0128017.

Similarity analyses (ANI and GGDC) of the sequenced genome of strain MS586T to other 40 genomes of the closely related Pseudomonas species were determined as briefed below. ANI based on pairwise comparison was calculated using the software JSpecies with the ANIb algorithm (Richter & Rosselló‐Móra, 2009). GGDC was calculated using the web service http://ggdc.dsmz.de and using the recommended BLAST+method (Meier‐Kolthoff et al., 2013). The GGDC results shown are based on the recommended formula 2 (sum of all identities found in HSPs divided by the overall HSP length), which is independent of the genome length and is thus robust against the use of incomplete draft genomes. The Type (Strain) Genome Server (https://www.dsmz.de/services/online‐tools/tygs) with the recommended settings was used to clarify species delineation (Meier‐Kolthoff & Göker, 2019). The phylogenomic tree based on whole‐genome sequences was reconstructed by Genome Blast Distance Phylogeny (GBDP). Accession numbers of sequences used in the whole‐genome phylogenetic analysis are summarized in Table A3. The clustering of the type‐based species using a 70% dDDH radius around each type strain was conducted as previously described (Meier‐Kolthoff & Göker, 2019).

2.6. Chemotaxonomic analysis

As important chemical characteristics for bacterial identification, the cellular fatty acid profile of the strain MS586T was analyzed. Cellular fatty acids were harvested after 2 days of growth at 28°C on TSA. Fatty acids extracted from the bacteria were methylated and analyzed following the protocol of the Sherlock 6.1 Microbial Identification (MIDI) system (Microbial IDentification Inc.) using the library RTSBA6 (Sasser, 1990). Analyses of respiratory quinones and polar lipids were carried out by the Identification Service of the DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Phenotype analysis

Both strains MS586T and MS82 were observed to be Gram‐negative, rod‐shaped (0.6–0.8 × 2.0–3.0 μm), and motile utilizing polar flagella (Figure A1). Colonies of the two strains were 3–5 mm in diameter and light yellow after 2 days of incubation on NBY at 28°C. No growth was detected at 40°C or with 7% NaCl. The optimum growth occurred at 28–30°C. The bacteria tolerated pH values ranging from 4 to 10. The two strains could produce fluorescent pigments when cultured for 24–48 hr at 28°C on King B medium, whereas Pseudomonas kribbensis 46‐2T, which is the closest species of strains MS586T and MS82, could not produce fluorescent (Table 1). Strain MS586T showed negative for assimilation of dextrin, formic acid, and d‐serine. In contrast, all these reactions were not negative for P. kribbensis 46‐2T, P. granadensis F‐278,770T, P. moraviensis 1B4T, and Pseudomonas koreensis Ps 9‐14T. Gelatin was hydrolyzed by strain MS586T, but it was negative by P. kribbensis 46‐2T. The physiological, morphological, and phenotypic characteristics in the API 20 NE, API 50 CH, and Biology GEN III tests, which allowed differentiation of strains MS586T from other closely related Pseudomonas species, are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Differentiating characteristics of strain MS586T from other related species of Pseudomonas

| Characteristics | 1 | 2a | 3b | 4c | 5c | 6d | 7e | 8e | 9e | 10e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flagellation | Polar, multiple | Polar, multiple | Polar, two | Polar, two | Polar, multiple | ND | ND | Polar, single | ND | ND |

| Fluorescence | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Growth at: | ||||||||||

| 4°C | + | + | + | + | + | + | ND | + | ND | ND |

| Tolerance of NaCl at | ||||||||||

| 5% | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Nitrate reduction | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| Arginine dihydrolase | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| Hydrolysis of gelatin | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Citrate utilization | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Urease | − | − | − | − | ND | − | − | − | − | − |

| Assimilation of | ||||||||||

| l‐Arabinose | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| N‐Acetyl‐d‐glucosamine | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Phenylacetic acid | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| d‐Mannose | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| Dextrin | − | + | w | + | + | − | + | + | + | − |

| Tween‐40 | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| d‐Cellobiose | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | − |

| d‐Trehalose | − | − | + | + | − | − | w | − | − | − |

| l‐Arabinose | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| d‐Fructose | + | + | + | + | + | + | ND | + | − | − |

| d‐Mannitol | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| d‐Arabitol | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| l‐Alanine | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | w | ND |

| l‐Serine | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | w | + |

| α‐Ketobutyric acid | − | − | w | + | + | − | − | + | + | − |

| α‐Ketoglutaric acid | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| Glucuronamide | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| l‐Histidine | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| d‐Serine | − | + | w | + | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| d‐Galactose | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| d‐Galacturonic acid | − | ND | − | − | ND | − | − | − | + | + |

| d‐Glucuronic acid | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Glucuronamide | − | + | + | ND | + | − | − | − | − | ND |

| p‐Hydroxy phenylacetic acid | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| Quinic acid | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| d‐Saccharic acid | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| Glycyl‐l‐proline | − | ND | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| l‐Pyroglutamic acid | + | + | + | + | ND | + | − | + | + | + |

| Inosine | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| Propionic acid | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | w | − |

| Formic acid | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| Acetic acid | + | + | w | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| Methyl pyruvate | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| GC content (%) | 60.5 | 60.5 | 59.9 | 60.3 | 59.1 | 58.7 | 67.2 | 62.2 | 59.1 | 59.4 |

Strains. 1, MS586T; 2, P. kribbensis 46‐2T; 3, P. granadensis F‐278,770T; 4, P. moraviensis 1B4T; 5, P. koreensis Ps9‐14T; 6, P. baetica a390T; 7, P. vancouverensis DhA‐51T; 8, P. jessenii DSM 17150T; 9, P. reinekei MT1T; 10, P. moorei RW10T. Data for strain MS586T were obtained in this study. Data for other type strains were obtained from references. a, (Chang et al., 2016); b, (Pascual, García‐López, Bills, & Genilloud, 2015); c, (Tvrzova et al., 2006); and d, (Lopez et al., 2012); e, (Camara et al., 2007).

Abbreviations: −, negative; +, positive; ND, not determined; W, weak.

3.2. Phylogenetic analysis

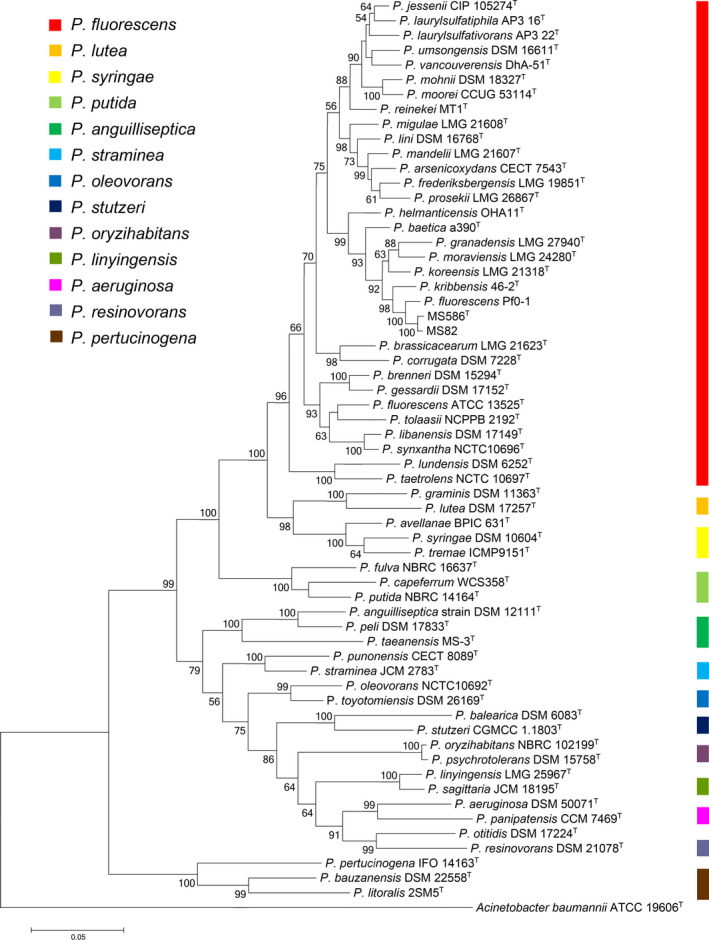

Sequence analysis revealed that the 16S rRNA genes of MS586T and MS82 shared significant identities (>98%) to some Pseudomonas species of the P. koreensis subgroup in the Pseudomonas fluorescens group. The closely related strains include P. kribbensis 46‐2T (99.94%), P. granadensis F‐278,770T (99.55%), P. koreensis Ps 9‐14T (99.52%), P. reinekei MT1T (99.46%), P. moraviensis 1B4T (99.41%), P. vancouverensis DhA‐51T (99.33%), P. baetica a390T (99.20%), P. jessenii DSM 17150T (98.94%), and P. fluorescens Pf0‐1 (99.87%). However, analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequence alone is insufficient to define the relative taxonomic positions of Pseudomonas species (Rosselló‐Móra & Whitman, 2018). Therefore, MLSA was conducted based on previously described methods using four gene sequences for the studies: 16S rRNA (1326 bp), rpoB (905 bp), rpoD (802 bp), and gyrB (663 bp). According to Hesse et al. (2018), the genus Pseudomonas has been phylogenetically divided into 13 groups (G) and 10 subgroups (SG). The closely related species of P. fluorescens subgroup and representative species of each group were selected to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree. The maximum‐likelihood tree illustrates the phylogenetic position of strain MS586T and 61 related members of the genus Pseudomonas based on four concatenated gene sequences (3696 bp); Acinetobacter baumannii strain ATCC 19606T was used as an outgroup. As shown in Figure 1, strains MS586T and MS82 were clustered with P. fluorescens Pf0‐1 with 100% bootstrap values. Strains MS586T and MS82 belong to the P. koreensis subgroup in the P. fluorescens group. It has been noted that, as reported by Gomila, Peña, Mulet, Lalucat, and García‐Valdés (2015), 30% of the genus Pseudomonas sequenced genomes of non‐type strains were not correctly assigned at the species level in the accepted taxonomy of the genus and 20% of the strains were not identified at the species level. Therefore, further extensive research is needed to update the Pseudomonas taxonomy.

FIGURE 1.

Maximum‐likelihood tree illustrating the phylogenetic position of strain MS586T and related members of the genus Pseudomonas using four concatenated gene sequences (3696 bp): 16S rRNA (1326 bp), rpoB (905 bp), rpoD (802 bp), and gyrB (663 bp). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. A. baumannii strain ATCC 19606T was used as the outgroup. Only bootstrap values above 50% are indicated. The colored bar designates groups of Pseudomonas spp. Accession numbers of sequences used in this study are summarized in Table A2

3.3. DNA fingerprinting

DNA fingerprinting by BOX‐PCR revealed that strains MS586T and MS82 were different representatives of the proposed novel species. As shown in Figure A2, two strains have the two common bands (490 bp and 900 bp) in the BOX‐PCR profiles; however, each of them produced unique bands (125 bp, 300 bp, 750 bp, and 1350 bp for MS586T; 700 bp, 750 bp, 1100 bp, and 1350 bp for MS82), which suggests the two strains are not identical isolates.

3.4. General taxonomic genome features of strain MS586T

The main characteristics of the whole‐genome sequence of strain MS586T are depicted in Table 2. No plasmid was detected. The DNA G+C content of strain MS586T was 60.48 mol%. This value is in the range (48–68 mol%) of those reported within the genus Pseudomonas (Hesse et al., 2018).

TABLE 2.

Chromosome statistics for strain MS586T

| Feature | Total |

|---|---|

| Size | 6,396,728 bp |

| Genes | 5893 |

| CDs | 5805 |

| Pseudogenes | 131 |

| rRNAs | 17 |

| tRNAs | 67 |

| ncRNA | 4 |

| G+C content | 60.48% |

All genome‐relatedness values of strain MS586T were calculated by the algorithms ANIb and GGDC. The MS586T genome was compared with the complete genome assemblies downloaded from NCBI for the strains shown in Table 3. ANI 95%–96% is equivalent to a DNA‐DNA hybridization of 70% (Kim, Oh, Park, & Chun, 2014). The species demarcations ANI ≥ 95% or GGDC ≥ 70% were used as a benchmark (Richter & Rosselló‐Móra, 2009). ANI values and GGDC values ranged from 75.28% to 98.24% and 21.00% to 84.10%, respectively, with the highest value between MS82 and MS586T. As shown in Table 3, strain MS586T shared less than 91% ANI and 35% GGDC with any of the other type strain of bacteria, but it had ANI value of 98.24% and GGDC value of 84.10% with strain MS82, which are higher than the species boundary cutoff values. Additionally, the two strains share 95.59% ANI and 65.30% GGDC with P. fluorescens Pf0‐1, which is the closest relative outside to the novel species. As reported by Lopes et al. (Lopes et al., 2018), three strains isolated from tropical soils, which share ≥95% ANI values with strain MS586T, are the potential strains for the novel species. As shown in Figure 2, the whole‐genome‐based phylogenetic tree obtained with TYGS automated pipeline shows that both MS586T and MS82 were grouped into the same species cluster and confirmed that P. kribbensis 46‐2T is the closely related type strain. P. fluorescens Pf0‐1 was clustered to independent branch, which indicates its distinct phylogenetic position and potential as a separate species. Collectively, the ANI, GGDC, and whole‐genome phylogenetic tree data support that strains MS586T and MS82 represent a unique species.

TABLE 3.

ANI (%) and GGDC (%) between strain MS586T and closely related sequenced strains of the genus Pseudomonas

| Pseudomonas species | Genome accession number at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena | ANI (%) | GGDC% |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. agarici LMG 2112T | GCA_900109755 | 79.87% | 24.30% |

| P. arsenicoxydans CECT 7543T | GCA_900103875 | 84.36% | 28.60% |

| P. azotoformans LMG 21611T | GCA_900103345 | 80.75% | 25.10% |

| P. baetica LMG 25716T | GCA_002813455 | 86.58% | 33.30% |

| P. entomophila L48T | GCA_000026105 | 77.45% | 22.40% |

| P. fluorescens ATCC 13525T | GCA_900215245 | 80.84% | 24.40% |

| P. frederiksbergensis LMG19851T | GCA_900105495 | 84.64% | 29.10% |

| P. fuscovaginae LMG 2158T | GCA_900108595 | 80.04% | 24.60% |

| P. gessardii DSM 17152T | GCA_001983165 | 80.81% | 25.00% |

| P. graminis DSM 11363T | GCA_900111735 | 77.72% | 22.70% |

| P. granadensis LMG 27940T | GCA_900105485 | 85.88% | 31.60% |

| P. jessenii DSM 17150T | GCA_002236115 | 84.40% | 29.70% |

| P. knackmussii B13T | GCA_000689415 | 75.51% | 21.00% |

| P. koreensis LMG 21318T | GCA_900101415 | 87.32% | 32.63% |

| P. kribbensis KCTC 32541T | GCA_003352185 | 90.22% | 42.20% |

| P. laurylsulfatiphila AP3_16T | GCA_002934665 | 84.74% | 29.70% |

| P. laurylsulfativorans AP3_22T | GCA_002906155 | 84.61% | 29.50% |

| P. libanensis DSM 17149T | GCA_001439685 | 80.41% | 24.50% |

| P. lini DSM 16768T | GCA_900104735 | 84.44% | 29.20% |

| P. lutea LMG 21974T | GCA_900110795 | 70.69% | 19.50% |

| P. mandelii LMG 2210T | GCA_900106065 | 84.41% | 28.90% |

| P. migulae LMG 21608T | GCA_900106025 | 84.51% | 29.40% |

| P. mohnii DSM 18327T | GCA_900105115 | 84.24% | 29.20% |

| P. monteilii DSM 14164T | GCA_000621245 | 77.07% | 21.80% |

| P. moorei DSM 12647T | GCA_900102045 | 84.76% | 29.30% |

| P. moraviensis LMG 24280T | GCA_900105805 | 85.75% | 31.70% |

| P. mucidolens LMG 2223T | GCA_900106045 | 80.17% | 24.50% |

| P. parafulva DSM 17004T | GCA_000425765 | 76.47% | 21.50% |

| P. plecoglossicida DSM 15088T | GCA_000730665 | 77.84% | 22.50% |

| P. prosekii LMG26867T | GCA_900105155 | 84.28% | 28.40% |

| P. punonensis LMG 26839T | GCA_900142655 | 75.28% | 21.50% |

| P. putida NCTC 10936T | GCA_900455645 | 77.34% | 22.30% |

| P. reinekei MT1T | GCA_001945365 | 84.16% | 29.00% |

| P. rhizosphaerae DSM 16299T | GCA_000761155 | 77.99% | 22.90% |

| P. synxantha NCTC 10696T | GCA_901482615 | 80.31% | 24.70% |

| P. umsongensis DSM 16611T | GCA_002236105 | 83.79% | 29.00% |

| P. vancouverensis DhA‐51T | GCA_004348895 | 83.95% | 28.80% |

| P. yamanorum LMG 27247T | GCA_900105735 | 80.67% | 25.10% |

| P. fluorescens Pf0‐1 | GCA_000012445 | 95.59% | 65.30% |

| MS82 | GCA_003055645 | 98.24% | 84.10% |

FIGURE 2.

Whole‐genome sequence tree generated with TYGS for strain MS586T and its closely related species of the genus Pseudomonas. Tree inferred with FastME from GBDP distances was calculated from genome sequences. Branch lengths are scaled in terms of GBDP distance formula d5; numbers above branches are GBDP pseudo‐bootstrap support values from 100 replications. The colored squares designate species cluster. Accession numbers of sequences used in this study are summarized in Table A3

Furthermore, strains MS586T and MS82 were noteworthy, which were isolated from the rhizosphere of soybean plants associated with fungal pathogen infections. Strain MS586T has shown remarkable antifungal activities against a broad range of plant fungal pathogens (Jia and Lu, unpublished). Similarly, our study has demonstrated that strain MS82 possesses antifungal activities against the mushroom fungal pathogen Mycogone perniciosa, but not the mushroom fungus (Ma et al., 2019). Furthermore, it has been reported that PafR gene confers resistance to the mushroom pathogenic fungus (Ma et al., 2017). As expected, the PafR gene was also found in strains MS586T. Therefore, it is not surprising that multiple nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene clusters, which are frequently associated with the production of antimicrobial compounds (Mootz & Marahiel, 1997), have been predicted from the genomes of the bacterial strains.

3.5. Chemotaxonomic analysis

Cellular fatty acids were identified using the Sherlock 6.1 system (Microbial IDentification Inc.) and the library RTSBA6 (Sasser, 1990). The majority of fatty acids for strain MS586T were C16:0 (22.9%), summed feature 3 (C16:1ω7c/C16:1ω6c) (23.57%), summed feature 8 (C18:1ω7c/C18:1ω6c) (13.37%), and C17:0 cyclo (10.28%). The similarity of the fatty acid profiles supports the affiliation of strain MS586T with the genus Pseudomonas. The three fatty acids typical of the genus Pseudomonas (C10:0 3‐OH, C12:0, and C12:0 3‐OH) were also identified in strain MS586T (Palleroni, 2005). Besides, the lowest amounts of fatty acid C16:0 (22.9%) were observed in strain MS586T than in the strains of closely related species (29.4–36.5%). Strain MS586T also contains the highest amounts of C10:0 3‐OH (6.6%) when compared to the reference strains (2.2%–5.4%). The detailed fatty acid profiles of strain MS586T and the type strains of closely related species are provided in Table 4. Two‐dimensional TLC analysis revealed that the polar lipids of strain MS586T were phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), diphosphatidylglycerol (DPG), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), three unidentified phospholipids (PL), and one unidentified lipid (L) (Figure A3). Strain MS586T contains higher amounts of PL and L as compared with those of the closest relative of P. kribbensis 46‐2T. As expected, the major polar lipid components of strain MS586T were PE, DPG, and PG, which agrees with data published previously for the genus Pseudomonas (Moore et al., 2006). Also, the major respiratory quinone of strain MS586T was Q‐9, which is consistent with other species in the genus Pseudomonas (Moore et al., 2006).

TABLE 4.

Cellular fatty acid profiles of strain MS586T and strains of closely related species

| Fatty acid | 1 | 2a | 3b | 4c | 5c | 6d | 7e | 8e | 9e | 10e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C10:0 3‐OH | 6.6 | 5.4 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 2.9 |

| C12:0 2‐OH | 5.5 | 6.8 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 5 | 5.5 | 3.8 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 3.5 |

| C12:0 3‐OH | 6.7 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 4 | 3.2 | 5.7 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 3.7 |

| C10:0 | 0.8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | ND | ND |

| C12:0 | 2.9 | ND | 1.5 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 3.8 | 4.7 | 3.6 | 2.8 |

| C14:0 | 0.6 | 1.2 | ND | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| C16:0 | 22.9 | 33.4 | 32 | 29 | 33 | 29.4 | 29.4 | 29.4 | 36.5 | 36 |

| C17:0 cyclo | 10.3 | 15.1 | 6.9 | 2.4 | 2 | 3.2 | 9.4 | 0.9 | 22.3 | 21 |

| C18:0 | 0.3 | 1.6 | ND | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| C19:0 ω8c | 1.2 | ND | ND | 0.2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.7 | 1.2 |

| Summed feature 3 | 23.6 | 16.8 | 36 | 36 | 37 | 39.5 | 30.8 | 38.1 | 28 | 23 |

| Summed feature 8 | 13.4 | 8.9 | 12 | 17 | 13 | 12.2 | 8.5 | 17.2 | 8.6 | 10 |

Strains. 1, MS586T; 2, P. kribbensis 46‐2T; 3, P. granadensis F‐278,770T; 4, P. moraviensis 1B4T; 5, P. koreensis Ps9‐14T; 6, P. baetica a390T; 7, P. vancouverensis DhA‐51T; 8, P. jessenii DSM 17150T; 9, P. reinekei MT1T; and 10, P. moorei RW10T. Data for strain MS586T were obtained in this study. Data for other type strains were obtained from references. a, (Chang et al., 2016); b, (Pascual et al., 2015); c, (Tvrzova et al., 2006); d, (Lopez et al., 2012); and e, (Camara et al., 2007). Values are percentages of total fatty acids.

Summed features represent groups of two or three fatty acids that cannot be separated by GC with the MIDI system. Summed feature 3 consists of C16:1ω7c/C16:1ω6c; summed feature 8 consists of C18:1ω7c/C18:1ω6c.

Abbreviation: ND, not detected/not reported.

4. CONCLUSIONS

Analyses of molecular, phenotypic, physiological, and biochemical characteristics are needed to discriminate between members of the genus Pseudomonas and other rRNA groups of aerobic “pseudomonads” (Palleroni, 2005). These analyses of strains MS586T and MS82 revealed its distinct characteristics of 16S rRNA and housekeeping gene sequences, ANI values, GGDC values, and phenotypic and chemotaxonomic assays as compared with those of other species and strains of the genus Pseudomonas. Collectively, these results demonstrate that strain MS586T and strain MS82 represent a novel species of the genus Pseudomonas. The name Pseudomonas glycinae sp. nov. is proposed with strain MS586T as the type strain. Strain MS586T is a motile Gram‐negative, rod‐shaped, strictly aerobic, catalase‐ and oxidase‐positive, fluorescent strain. These findings support the placement of strain MS586T in the genus Pseudomonas (Hildebrand, Palleroni, Hendson, Toth, & Johnson, 1994).

4.1. Description of Pseudomonas glycinae sp. nov.

Pseudomonas glycinae (gly.ci'nae. N.L. gen. n. glycinae of Glycine max, soybean) is an aerobic, Gram‐negative, rod‐shaped bacterium, with motility through polar flagella. When cultured on NBY agar plates, it produces fluorescence and forms fresh light‐yellow colonies. The colony is raised from the side view, the shape is circular, and it is usually 3.0–5.0 mm in diameter within 2 days of growth at 28°C. Cells are 0.6–0.8 × 2.0–3.0 μm. Growth occurs between 4°C and 36°C (optimum growth temperature is 28–30°C). Growth occurs between pH 4 and 10 (optimum pH 6–7). The organism tolerates up to 6% (w/v) NaCl. The results obtained with Biology GENIII Microplates indicate the following substrates can be utilized: α‐d‐glucose, d‐mannose, d‐fructose, d‐fucose, d‐galactose, d‐mannitol, l‐alanine, l‐arginine, l‐aspartic acid, l‐glutamic acid, l‐pyroglutamic acid, l‐serine, d‐gluconic acid, mucic acid, quinic acid, d‐saccharic acid, l‐lactic acid, citric acid, α‐ketoglutaric acid, l‐malic acid, γ‐aminobutyric acid, β‐hydroxy‐d,l‐butyric acid, propionic acid, acetic acid, and N‐acetyl‐d‐glucosamine, but negative for dextrin, d‐maltose, d‐trehalose, d‐cellobiose, gentiobiose, sucrose, stachyose, d‐raffinose, α‐d‐lactose, d‐melibiose, β‐methyl‐d‐glucoside, d‐salicin, N‐acetyl‐β‐d‐mannosamine, N‐acetyl‐d‐galactosamine, N‐acetyl neuraminic acid, 3‐methyl glucose, l‐rhamnose, inosine, d‐sorbitol, d‐arabitol, myo‐inositol, d‐glucose‐6‐PO4, d‐fructose‐6‐PO4, d‐aspartic acid, d‐serine, gelatin, glycyl‐l‐proline, l‐histidine, pectin, d‐galacturonic acid, l‐galactonic acid lactone, d‐glucuronic acid, glucuronamide, p‐hydroxy‐phenylacetic acid, methyl pyruvate, d‐lactic acid methyl ester, d‐malic acid, Tween‐40, α‐hydroxybutyric acid, α‐ketobutyric acid, acetoacetic acid, and formic acid. According to API 20 NE tests, the organism is positive for the hydrolysis of gelatin, arginine dihydrolase, and assimilation of glucose, arabinose, mannose, mannitol, N‐acetyl‐glucosamine, potassium gluconate, capric acid, malic acid, and trisodium citrate, but negative for the reduction of nitrate to nitrogen and nitrogen, indole production, glucose fermentation, urease, hydrolysis of esculin and β‐galactosidase, and assimilation of maltose, adipic acid, and phenylacetic acid. According to API 50 CH tests, the organism is positive for acid production from l‐arabinose, d‐ribose, d‐xylose, d‐mannose, d‐mannitol, and d‐fucose, but negative for erythritol, d‐arabinose, l‐xylose, d‐adonitol, methyl‐β‐d‐xylopyranoside, d‐galactose, d‐fructose, d‐sorbose, l‐rhamnose, dulcitol, inositol, d‐sorbitol, methyl‐α‐d‐mannopyranoside, methyl‐α‐d‐glucopyranoside, amygdalin, arbutin, esculin, salicin, d‐cellobiose, d‐maltose, d‐melibiose, sucrose, d‐trehalose, inulin, d‐melezitose, d‐raffinose, starch, glycogen, xylitol, gentiobiose, d‐turanose, d‐lyxose, d‐tagatose, l‐fucose, d‐arabitol, l‐arabitol, potassium 2‐ketogluconate, and potassium 5‐ketogluconate. The predominant quinone system is Q‐9. Polar lipids are diphosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, three unidentified phospholipids, and one unidentified lipid. The type strain is MS586T (LMG 30275T, NRRL B‐65441T), isolated from the rhizosphere of soybean grown in Mississippi. The DNA G+C content of the type strain is 60.48 mol%.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jiayuan Jia: Formal analysis (equal); visualization (equal); writing – original draft (equal). Xiaoqiang Wang: Formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); writing – original draft (equal). Peng Deng: Formal analysis (equal). Lin Ma: Formal analysis (equal); resources (equal). Sonya M. Baird: Methodology (equal). Xiangdong Li: Formal analysis (equal); funding acquisition (equal). Shi‐En Lu: Conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (equal); funding acquisition (equal); project administration (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review & editing (equal).

ETHICS STATEMENT

None required.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture (MIS‐401200). We appreciate Kate Phillips for English proofreading.

Appendix A.

FIGURE A1.

The cellular morphology of strain MS586T was observed by transmission electron microscopy

FIGURE A2.

Fingerprinting analysis of strain MS586T and strain MS82 based on analysis of BOX‐PCR: 1, strain MS586T; 2, strain MS82; Mk: 1‐kb DNA ladder (GoldBio) was used with markers

FIGURE A3.

Two‐dimensional TLC of polar lipids of strain MS586T. DPG, diphosphatidylglycerol; L, lipid; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; PL, phospholipid

TABLE A1.

List of strains used in this study

| Species | Strain | Source collection |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas glycinae | MS586 | This study |

| Pseudomonas glycinae | MS82 | Ma et al. (2017) |

| Pseudomonas moraviensis | 1B4 | DSMZ |

| Pseudomonas jessenii | CIP105274 | DSMZ |

| Pseudomonas reinekei | MT1 | DSMZ |

| Pseudomonas vancouverensis | DhA‐51 | DSMZ |

| Pseudomonas baetica | a390 | DSMZ |

DSMZ: German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Braunschweig, Germany.

TABLE A2.

Accession numbers of the sequences of different Pseudomonas spp. strains used in the MLSA phylogenetic analysis

| Species | Gene name | Accession number | Strain designation | Species | Gene name | Accession number | Strain designation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. glycinae | 16S rRNA | MG692779 | MS586T | P. glycinae | 16S rRNA | CP028826 | MS82 |

| rpoB | CP014205 | MS586T | rpoB | CP028826 | MS82 | ||

| rpoD | CP014205 | MS586T | rpoD | CP028826 | MS82 | ||

| gyrB | CP014205 | MS586T | gyrB | CP028826 | MS82 | ||

| P. fluorescens | 16S rRNA | CP000094 | Pf0‐1 | P. aeruginosa | 16S rRNA | CP012001 | DSM 50071T |

| rpoB | CP000094 | Pf0‐1 | rpoB | CP012001 | DSM 50071T | ||

| rpoD | CP000094 | Pf0‐1 | rpoD | CP012001 | DSM 50071T | ||

| gyrB | CP000094 | Pf0‐1 | gyrB | CP012001 | DSM 50071T | ||

| P. anguilliseptica | 16S rRNA | FNSC00000000 | DSM 12111T | P. arsenicoxydans | 16S rRNA | LT629705 | CECT 7543T |

| rpoB | FNSC00000000 | DSM 12111T | rpoB | LT629705 | CECT 7543T | ||

| rpoD | FNSC00000000 | DSM 12111T | rpoD | LT629705 | CECT 7543T | ||

| gyrB | FNSC00000000 | DSM 12111T | gyrB | LT629705 | CECT 7543T | ||

| P. avellanae | 16S rRNA | AKBS00000000 | BPIC 631T | P. baetica | 16S rRNA | PKLC00000000 | a390T |

| rpoB | AKBS00000000 | BPIC 631T | rpoB | PKLC00000000 | a390T | ||

| rpoD | AKBS00000000 | BPIC 631T | rpoD | PKLC00000000 | a390T | ||

| gyrB | AKBS00000000 | BPIC 631T | gyrB | PKLC00000000 | a390T | ||

| P. balearica | 16S rRNA | CP007511 | DSM 6083T | P. bauzanensis | 16S rRNA | FOGN00000000 | DSM 22558T |

| rpoB | CP007511 | DSM 6083T | rpoB | FOGN00000000 | DSM 22558T | ||

| rpoD | CP007511 | DSM 6083T | rpoD | FOGN00000000 | DSM 22558T | ||

| gyrB | CP007511 | DSM 6083T | gyrB | FOGN00000000 | DSM 22558T | ||

| P. brassicacearum | 16S rRNA | LT629713 | LMG 21623T | P. brenneri | 16S rRNA | VFIL00000000 | DSM 15294T |

| rpoB | LT629713 | LMG 21623T | rpoB | VFIL00000000 | DSM 15294T | ||

| rpoD | LT629713 | LMG 21623T | rpoD | VFIL00000000 | DSM 15294T | ||

| gyrB | LT629713 | LMG 21623T | gyrB | VFIL00000000 | DSM 15294T | ||

| P. capeferrum | 16S rRNA | JMIT00000000 | WCS358T | P. corrugata | 16S rRNA | LHVK00000000 | DSM 7228T |

| rpoB | JMIT00000000 | WCS358T | rpoB | LHVK00000000 | DSM 7228T | ||

| rpoD | JMIT00000000 | WCS358T | rpoD | LHVK00000000 | DSM 7228T | ||

| gyrB | JMIT00000000 | WCS358T | gyrB | LHVK00000000 | DSM 7228T | ||

| P. fluorescens | 16S rRNA | LT907842 | ATCC 13525T | P. frederiksbergensis | 16S rRNA | FNTF00000000 | LMG 19851T |

| rpoB | LT907842 | ATCC 13525T | rpoB | FNTF00000000 | LMG 19851T | ||

| rpoD | LT907842 | ATCC 13525T | rpoD | FNTF00000000 | LMG 19851T | ||

| gyrB | LT907842 | ATCC 13525T | gyrB | FNTF00000000 | LMG 19851T | ||

| P. fulva | 16S rRNA | BBIQ00000000 | NBRC 16637T | P. gessardii | 16S rRNA | VFEW00000000 | DSM 17152T |

| rpoB | BBIQ00000000 | NBRC 16637T | rpoB | VFEW00000000 | DSM 17152T | ||

| rpoD | BBIQ00000000 | NBRC 16637T | rpoD | VFEW00000000 | DSM 17152T | ||

| gyrB | BBIQ00000000 | NBRC 16637T | gyrB | VFEW00000000 | DSM 17152T | ||

| P. graminis | 16S rRNA | FOHW00000000 | DSM 11363T | P. granadensis | 16S rRNA | LT629778 | LMG 27940T |

| rpoB | FOHW00000000 | DSM 11363T | rpoB | LT629778 | LMG 27940T | ||

| rpoD | FOHW00000000 | DSM 11363T | rpoD | LT629778 | LMG 27940T | ||

| gyrB | FOHW00000000 | DSM 11363T | gyrB | LT629778 | LMG 27940T | ||

| P. helmanticensis | 16S rRNA | HG940537 | OHA11T | P. jessenii | 16S rRNA | NIWT01000000 | DSM 17150T |

| rpoB | HG940518 | OHA11T | rpoB | NIWT01000000 | DSM 17150T | ||

| rpoD | HG940517 | OHA11T | rpoD | NIWT01000000 | DSM 17150T | ||

| gyrB | HG940516 | OHA11T | gyrB | NIWT01000000 | DSM 17150T | ||

| P. koreensis | 16S rRNA | LT629687 | LMG 21318T | P. kribbensis | 16S rRNA | CP029608 | 46‐2T |

| rpoB | LT629687 | LMG 21318T | rpoB | CP029608 | 46‐2T | ||

| rpoD | LT629687 | LMG 21318T | rpoD | CP029608 | 46‐2T | ||

| gyrB | LT629687 | LMG 21318T | gyrB | CP029608 | 46‐2T | ||

| P. laurylsulfatiphila | 16S rRNA | NIRS00000000 | AP3_16T | P. laurylsulfativorans | 16S rRNA | MUJK00000000 | AP3_22T |

| rpoB | NIRS00000000 | AP3_16T | rpoB | MUJK00000000 | AP3_22T | ||

| rpoD | NIRS00000000 | AP3_16T | rpoD | MUJK00000000 | AP3_22T | ||

| gyrB | NIRS00000000 | AP3_16T | gyrB | MUJK00000000 | AP3_22T | ||

| P. libanensis | 16S rRNA | JYLH00000000 | DSM 17149T | P. lini | 16S rRNA | JYLB00000000 | DSM 16768T |

| rpoB | JYLH00000000 | DSM 17149T | rpoB | JYLB00000000 | DSM 16768T | ||

| rpoD | JYLH00000000 | DSM 17149T | rpoD | JYLB00000000 | DSM 16768T | ||

| gyrB | JYLH00000000 | DSM 17149T | gyrB | JYLB00000000 | DSM 16768T | ||

| P. linyingensis | 16S rRNA | FNZE00000000 | LMG 25967T | P. litoralis | 16S rRNA | LT629748 | 2SM5T |

| rpoB | FNZE00000000 | LMG 25967T | rpoB | LT629748 | 2SM5T | ||

| rpoD | FNZE00000000 | LMG 25967T | rpoD | LT629748 | 2SM5T | ||

| gyrB | FNZE00000000 | LMG 25967T | gyrB | LT629748 | 2SM5T | ||

| P. lundensis | 16S rRNA | JYKY00000000 | DSM 6252T | P. lutea | 16S rRNA | JRMB00000000 | DSM 17257T |

| rpoB | JYKY00000000 | DSM 6252T | rpoB | JRMB00000000 | DSM 17257T | ||

| rpoD | JYKY00000000 | DSM 6252T | rpoD | JRMB00000000 | DSM 17257T | ||

| gyrB | JYKY00000000 | DSM 6252T | gyrB | JRMB00000000 | DSM 17257T | ||

| P. mandelii | 16S rRNA | LT629796 | LMG 21607T | P. migulae | 16S rRNA | FNTY00000000 | LMG 21608T |

| rpoB | LT629796 | LMG 21607T | rpoB | FNTY00000000 | LMG 21608T | ||

| rpoD | LT629796 | LMG 21607T | rpoD | FNTY00000000 | LMG 21608T | ||

| gyrB | LT629796 | LMG 21607T | gyrB | FNTY00000000 | LMG 21608T | ||

| P. mohnii | 16S rRNA | FNRV01000000 | DSM 18327T | P. moorei | 16S rRNA | VZPP00000000 | CCUG 53114T |

| rpoB | FNRV01000000 | DSM 18327T | rpoB | VZPP00000000 | CCUG 53114T | ||

| rpoD | FNRV01000000 | DSM 18327T | rpoD | VZPP00000000 | CCUG 53114T | ||

| gyrB | FNRV01000000 | DSM 18327T | gyrB | VZPP00000000 | CCUG 53114T | ||

| P. moraviensis | 16S rRNA | LT629788 | LMG 24280T | P. oleovorans | 16S rRNA | UGUV00000000 | NCTC10692T |

| rpoB | LT629788 | LMG 24280T | rpoB | UGUV00000000 | NCTC10692T | ||

| rpoD | LT629788 | LMG 24280T | rpoD | UGUV00000000 | NCTC10692T | ||

| gyrB | LT629788 | LMG 24280T | gyrB | UGUV00000000 | NCTC10692T | ||

| P. oryzihabitans | 16S rRNA | BBIT00000000 | NBRC 102199T | P. otitidis | 16S rRNA | FOJP00000000 | DSM 17224T |

| rpoB | BBIT00000000 | NBRC 102199T | rpoB | FOJP00000000 | DSM 17224T | ||

| rpoD | BBIT00000000 | NBRC 102199T | rpoD | FOJP00000000 | DSM 17224T | ||

| gyrB | BBIT00000000 | NBRC 102199T | gyrB | FOJP00000000 | DSM 17224T | ||

| P. panipatensis | 16S rRNA | FNDS00000000 | CCM 7469T | P. peli | 16S rRNA | FMTL00000000 | DSM 17833T |

| rpoB | FNDS00000000 | CCM 7469T | rpoB | FMTL00000000 | DSM 17833T | ||

| rpoD | FNDS00000000 | CCM 7469T | rpoD | FMTL00000000 | DSM 17833T | ||

| gyrB | FNDS00000000 | CCM 7469T | gyrB | FMTL00000000 | DSM 17833T | ||

| P. pertucinogena | 16S rRNA | AB021380 | IFO 14163T | P. prosekii | 16S rRNA | LT629762 | LMG 26867T |

| rpoB | AJ717441 | LMG 1874T | rpoB | LT629762 | LMG 26867T | ||

| rpoD | FN554502 | LMG 1874T | rpoD | LT629762 | LMG 26867T | ||

| gyrB | DQ350613 | JCM 11950T | gyrB | LT629762 | LMG 26867T | ||

| P. psychrotolerans | 16S rRNA | FMWB00000000 | DSM 15758T | P. punonensis | 16S rRNA | FRBQ00000000 | CECT 8089T |

| rpoB | FMWB00000000 | DSM 15758T | rpoB | FRBQ00000000 | CECT 8089T | ||

| rpoD | FMWB00000000 | DSM 15758T | rpoD | FRBQ00000000 | CECT 8089T | ||

| gyrB | FMWB00000000 | DSM 15758T | gyrB | FRBQ00000000 | CECT 8089T | ||

| P. putida | 16S rRNA | AP013070 | NBRC 14164T | P. reinekei | 16S rRNA | MSTQ00000000 | MT1T |

| rpoB | AP013070 | NBRC 14164T | rpoB | MSTQ00000000 | MT1T | ||

| rpoD | AP013070 | NBRC 14164T | rpoD | MSTQ00000000 | MT1T | ||

| gyrB | AP013070 | NBRC 14164T | gyrB | MSTQ00000000 | MT1T | ||

| P. resinovorans | 16S rRNA | AUIE00000000 | DSM 21078T | P. sagittaria | 16S rRNA | FOXM00000000 | JCM 18195T |

| rpoB | AUIE00000000 | DSM 21078T | rpoB | FOXM00000000 | JCM 18195T | ||

| rpoD | AUIE00000000 | DSM 21078T | rpoD | FOXM00000000 | JCM 18195T | ||

| gyrB | AUIE00000000 | DSM 21078T | gyrB | FOXM00000000 | JCM 18195T | ||

| P. straminea | 16S rRNA | FOMO01000000 | JCM 2783T | P. stutzeri | 16S rRNA | CP002881 | CGMCC 1.1803T |

| rpoB | FOMO01000000 | JCM 2783T | rpoB | CP002881 | CGMCC 1.1803T | ||

| rpoD | FOMO01000000 | JCM 2783T | rpoD | CP002881 | CGMCC 1.1803T | ||

| gyrB | FOMO01000000 | JCM 2783T | gyrB | CP002881 | CGMCC 1.1803T | ||

| P. synxantha | 16S rRNA | LR590482 | NCTC10696T | P. syringae | 16S rRNA | JALK00000000 | DSM 10604T |

| rpoB | LR590482 | NCTC10696T | rpoB | JALK00000000 | DSM 10604T | ||

| rpoD | LR590482 | NCTC10696T | rpoD | JALK00000000 | DSM 10604T | ||

| gyrB | LR590482 | NCTC10696T | gyrB | JALK00000000 | DSM 10604T | ||

| P. taeanensis | 16S rRNA | AWSQ00000000 | MS‐3T | P. taetrolens | 16S rRNA | LS483370 | NCTC 10697T |

| rpoB | AWSQ00000000 | MS‐3T | rpoB | LS483370 | NCTC 10697T | ||

| rpoD | AWSQ00000000 | MS‐3T | rpoD | LS483370 | NCTC 10697T | ||

| gyrB | AWSQ00000000 | MS‐3T | gyrB | LS483370 | NCTC 10697T | ||

| P. tolaasii | 16S rRNA | PHHD00000000 | NCPPB 2192T | P. toyotomiensis | 16S rRNA | NIQV00000000 | DSM 26169T |

| rpoB | PHHD00000000 | NCPPB 2192T | rpoB | NIQV00000000 | DSM 26169T | ||

| rpoD | PHHD00000000 | NCPPB 2192T | rpoD | NIQV00000000 | DSM 26169T | ||

| gyrB | PHHD00000000 | NCPPB 2192T | gyrB | NIQV00000000 | DSM 26169T | ||

| P. tremae | 16S rRNA | LJRO00000000 | ICMP9151T | P. umsongensis | 16S rRNA | NIWU00000000 | DSM 16611T |

| rpoB | LJRO00000000 | ICMP9151T | rpoB | NIWU00000000 | DSM 16611T | ||

| rpoD | LJRO00000000 | ICMP9151T | rpoD | NIWU00000000 | DSM 16611T | ||

| gyrB | LJRO00000000 | ICMP9151T | gyrB | NIWU00000000 | DSM 16611T | ||

| P. vancouverensis | 16S rRNA | RRZK00000000 | Dha‐51T | Acinetobacter baumannii | 16S rRNA | MJHA00000000 | ATCC 19606T |

| rpoB | RRZK00000000 | Dha‐51T | rpoB | MJHA00000000 | ATCC 19606T | ||

| rpoD | RRZK00000000 | Dha‐51T | rpoD | MJHA00000000 | ATCC 19606T | ||

| gyrB | RRZK00000000 | Dha‐51T | gyrB | MJHA00000000 | ATCC 19606T |

TABLE A3.

Accession numbers of the sequences of different Pseudomonas spp. strains used in the whole‐genome phylogenetic analysis

| Species | Accession number | Strain designation |

|---|---|---|

| P. glycinae | GCA_001594225 | MS586T |

| P. glycinae | GCA_003055645 | MS82 |

| P. fluorescens | GCA_000012445 | Pf0‐1 |

| P. arsenicoxydans | GCA_900103875 | CECT 7543T |

| P. baetica | GCA_002813455 | LMG 25716T |

| P. batumici | GCA_000820515 | UCM B‐321T |

| P. chlororaphis | GCA_001269625 | LMG 5004T |

| P. frederiksbergensis | GCA_900105495 | LMG 19851T |

| P. granadensis | GCA_900105485 | LMG 27940T |

| P. jessenii | GCA_002236115 | DSM 17150T |

| P. koreensis | GCA_900101415 | LMG 21318T |

| P. kribbensis | GCA_003352185 | 46‐2T |

| P. laurylsulfatiphila | GCA_002934665 | AP3_16T |

| P. laurylsulfativorans | GCA_002906155 | AP3_22T |

| P. lini | GCA_001042905 | DSM 16768T |

| P. moorei | GCA_900102045 | DSM 12647T |

| P. moraviensis | GCA_900105805 | LMG 24280T |

| P. prosekii | GCA_900105155 | LMG 26867T |

| P. reinekei | GCA_001945365 | MT1T |

| P. vancouverensis | GCA_900105825 | LMG 202221T |

Jia J, Wang X, Deng P, et al., Pseudomonas glycinae sp. nov. isolated from the soybean rhizosphere. MicrobiologyOpen. 2020;9:e1101 10.1002/mbo3.1101

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The GenBank accession numbers for the complete genome of Pseudomonas glycinae MS586T and the full‐length sequence of 16S rDNA are CP014205 and MG692779, respectively. The type strain MS586T was deposited in the ARS Culture Collection, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Peoria, IL, USA (Culture collection 1 accession #NRRL B‐6544: https://nrrl.ncaur.usda.gov/cgi‐bin/usda/prokaryote/report.html?nrrlcodes=B‐65441), and the BCCM/LMG Bacteria Collection, Laboratorium voor Microbiologie, Universiteit Gent, Belgium (Culture collection 2 accession #LMG 30275: https://bccm.belspo.be/catalogues/lmg-strain-details?NUM=30275).

REFERENCES

- Angiuoli, S. V. , Gussman, A. , Klimke, W. , Cochrane, G. , Field, D. , Garrity, G. M. , … White, O. (2008). Toward an online repository of standard operating procedures (SOPs) for (meta) genomic annotation. OMICS A Journal of Integrative Biology, 12(2), 137–141. 10.1089/omi.2008.0017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camara, B. , Strömpl, C. , Verbarg, S. , Spröer, C. , Pieper, D. H. , & Tindall, B. J. (2007). Pseudomonas reinekei sp. nov., Pseudomonas moorei sp. nov. and Pseudomonas mohnii sp. nov., novel species capable of degrading chlorosalicylates or isopimaric acid. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 57(5), 923–931. 10.1099/ijs.0.64703-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, D.‐H. , Rhee, M.‐S. , Kim, J.‐S. , Lee, Y. , Park, M. Y. , Kim, H. , … Kim, B.‐C. (2016). Pseudomonas kribbensis sp. nov., isolated from garden soils in Daejeon, Korea. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 109(11), 1433–1446. 10.1007/s10482-016-0743-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelius, M. K. , & Triplett, E. W. (2000). Immunolocalization of dinitrogenase reductase produced by Klebsiella pneumoniae in association with Zea mays L. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 66, 783–787. 10.1128/AEM.66.2.783-787.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, J. J. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Durfee, T. , Nelson, R. , Baldwin, S. , Plunkett, G. , Burland, V. , Mau, B. , … Blattner, F. R. (2008). The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli DH10B: Insights into the biology of a laboratory workhorse. Journal of Bacteriology, 190(7), 2597–2606. 10.1128/JB.01695-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furmanczyk, E. M. , Kaminski, M. A. , Lipinski, L. , Dziembowski, A. , & Sobczak, A. (2018). Pseudomonas laurylsulfatovorans sp. nov., sodium dodecyl sulfate degrading bacteria, isolated from the peaty soil of a wastewater treatment plant. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 41(4), 348–354. 10.1016/j.syapm.2018.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomila, M. , Peña, A. , Mulet, M. , Lalucat, J. , & García‐Valdés, E. (2015). Phylogenomics and systematics in Pseudomonas . Frontiers in Microbiology, 6, 214 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, G. , Wang, N. , Chaney, N. , Smith, L. , & Lu, S.‐E. (2009). AmbR1 is a key transcriptional regulator for production of antifungal activity of Burkholderia contaminans strain MS14. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 297(1), 54–60. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01653.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, C. , Schulz, F. , Bull, C. T. , Shaffer, B. T. , Yan, Q. , Shapiro, N. , … Paulsen, I. T. (2018). Genome‐based evolutionary history of Pseudomonas spp. Environmental Microbiology, 20(6), 2142–2159. 10.1111/1462-2920.14130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, D. , Palleroni, N. , Hendson, M. , Toth, J. , & Johnson, J. (1994). Pseudomonas flavescens sp. nov., isolated from walnut blight cankers. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 44, 410–415. 10.1099/00207713-44-3-410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. , Oh, H.‐S. , Park, S.‐C. , & Chun, J. (2014). Towards a taxonomic coherence between average nucleotide identity and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity for species demarcation of prokaryotes. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 64, 346–351. 10.1099/ijs.0.059774-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, E. O. , Ward, M. K. , & Raney, D. E. (1954). Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescein. The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine, 44(2), 301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeuth, T. , Versalovic, J. , & Lupski, J. R. (1995). Differential subsequence conservation of interspersed repetitive Streptococcus pneumoniae BOX elements in diverse bacteria. Genome Research, 5(4), 408–418. 10.1101/gr.5.4.408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidis, K. T. , & Tiedje, J. M. (2005). Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(7), 2567–2572. 10.1073/pnas.0409727102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. , Stecher, G. , & Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 33(7), 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane, D. J. (1991). 16S/23S rRNA sequencing In Stackebrandt E., & Goodfellow M. (Eds.), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics (pp. 125–175). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, L. D. , Davis, E. W. , Pereira e Silva, M. D. C. , Weisberg, A. J. , Bresciani, L. , … Andreote, F. D. (2018). Tropical soils are a reservoir for fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. biodiversity. Environmental Microbiology, 20(1), 62–74. 10.1111/1462-2920.13957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López, J. R. , Diéguez, A. L. , Doce, A. , De la Roca, E. , De la Herran, R. , Navas, J. I. , … Romalde, J. L. (2012). Pseudomonas baetica sp. nov., a fish pathogen isolated from wedge sole, Dicologlossa cuneata (Moreau). International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 62(4), 874–882. 10.1099/ijs.0.030601-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L. , Qu, S. , Lin, J. , Jia, J. , Baird, S. M. , Jiang, N. , … Lu, S.‐E. (2019). The complete genome of the antifungal bacterium Pseudomonas sp. strain MS82. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, 126(2), 153–160. 10.1007/s41348-019-00205-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L. , Wang, X. , Deng, P. , Baird, S. M. , Liu, Y. , Qu, S. , & Lu, S.‐E. (2017). The PafR gene is required for antifungal activity of strain MS82 against Mycogone perniciosa . Advances in Microbiology, 7(4), 217–230. 10.4236/aim.2017.74018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meier‐Kolthoff, J. P. , Auch, A. F. , Klenk, H.‐P. , & Göker, M. (2013). Genome sequence‐based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics, 14(1), 60 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier‐Kolthoff, J. P. , & Göker, M. (2019). TYGS is an automated high‐throughput platform for state‐of‐the‐art genome‐based taxonomy. Nature Communications, 10(1), 1–10. 10.1038/s41467-019-10210-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migula, W. (1894). Über ein neues system der bakterien. Arb Bakteriol Inst Karlsruhe, 1, 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, E. R. B. , Mau, M. , Arnscheidt, A. , Böttger, E. C. , Hutson, R. A. , Collins, M. D. , … Timmis, K. N. (1996). The determination and comparison of the 16S rRNA gene sequences of species of the genus Pseudomonas (sensu stricto) and estimation of the natural intrageneric relationships. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 19, 478–492. 10.1016/S0723-2020(96)80021-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, E. R. , Tindall, B. J. , Martins Dos Santos, V. , Pieper, D. H. , Ramos, J.‐L. , & Palleroni, N. J. (2006). Nonmedical: Pseudomonas . The Prokaryotes, 6, 646–703. [Google Scholar]

- Mootz, H. D. , & Marahiel, M. A. (1997). Biosynthetic systems for nonribosomal peptide antibiotic assembly. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 1(4), 543–551. 10.1016/S1367-5931(97)80051-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulet, M. , Bennasar, A. , Lalucat, J. , & García‐Valdés, E. (2009). An rpoD‐based PCR procedure for the identification of Pseudomonas species and for their detection in environmental samples. Molecular and Cellular Probes, 23, 140–147. 10.1016/j.mcp.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, R. G. E. , Doetsch, R. N. , & Robinow, C. F. (1994). Determination and cytological light microscopy In Gerhardt P., Murray R. G. E., Wood W. A., & Krieg N. R. (Eds.), Methods for general and molecular bacteriology (pp. 32–34). Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology. [Google Scholar]

- Oueslati, M. , Mulet, M. , Gomila, M. , Berge, O. , Hajlaoui, M. R. , Lalucat, J. , & García‐Valdés, E. (2019). New species of pathogenic Pseudomonas isolated from citrus in Tunisia: Proposal of Pseudomonas kairouanensis sp. nov. and Pseudomonas nabeulensis sp. nov. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 42(3), 348–359. 10.1016/j.syapm.2019.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palleroni, N. J. (1994). Pseudomonas classification. A new case history in the taxonomy of gram‐negative bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 64, 231–251. 10.1007/BF00873084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palleroni, N. J. (2005). Genus I. Pseudomonas migula 1894, 237AL (Nom. Cons., Opin. 5 of the Jud. Comm. 1952, 121) In Boone D. R., Brenner D. J., Castenholz R. W., Garrity G. M., Krieg N. R., & Staley J. T. (Eds.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology (2nd ed., pp. 323–379). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, J. , García‐López, M. , Bills, G. F. , & Genilloud, O. (2015). Pseudomonas granadensis sp. nov., a new bacterial species isolated from the Tejeda, Almijara and Alhama Natural Park, Granada, Spain. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 65(2), 625–632. 10.1099/ijs.0.069260-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, J. , Macián, M. C. , Arahal, D. R. , Garay, E. , & Pujalte, M. J. (2010). Multilocus sequence analysis of the central clade of the genus Vibrio by using the 16S rRNA, recA, pyrH, rpoD, gyrB, rctB and toxR genes. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 60, 154–165. 10.1099/ijs.0.010702-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peix, A. , Berge, O. , Rivas, R. , Abril, A. , & Velázquez, E. (2005). Pseudomonas argentinensis sp. nov., a novel yellow pigment‐producing bacterial species, isolated from rhizospheric soil in Cordoba, Argentina. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 55(3), 1107–1112. 10.1099/ijs.0.63445-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peix, A. , Ramirez‐Bahena, M.‐H. , & Velazquez, E. (2018). The current status on the taxonomy of Pseudomonas revisited: An update. Infection, Genetics and Evolution, 57, 106–116. 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter, M. , & Rosselló‐Móra, R. (2009). Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106, 19126–19131. 10.1073/pnas.0906412106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosselló‐Móra, R. , & Amann, R. (2015). Past and future species definitions for bacteria and Archaea . Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 38, 209–216. 10.1016/j.syapm.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosselló‐Móra, R. , & Whitman, W. B. (2018). Dialogue on the nomenclature and classification of prokaryotes. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 42(1), 5–14. 10.1016/j.syapm.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasser, M. (1990). Identification of bacteria by gas chromatography of cellular fatty acids. MIDI Technical Note #101. [Google Scholar]

- Sneath, P. H. A. , Stevens, M. , & Sackin, M. J. (1981). Numerical taxonomy of Pseudomonas based on published records of substrate utilization. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 47, 423–448. 10.1007/BF00426004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayeb, L. A. , Ageron, E. , Grimont, F. , & Grimont, P. (2005). Molecular phylogeny of the genus Pseudomonas based on rpoB sequences and application for the identification of isolates. Research in Microbiology, 156, 763–773. 10.1016/j.resmic.2005.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tvrzová, L. , Schumann, P. , Spröer, C. , Sedláček, I. , Páčová, Z. , Šedo, O. , … Lang, E. (2006). Pseudomonas moraviensis sp. nov. and Pseudomonas vranovensis sp. nov., soil bacteria isolated on nitroaromatic compounds, and emended description of Pseudomonas asplenii . International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 56(11), 2657–2663. 10.1099/ijs.0.63988-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidaver, A. M. (1967). Synthetic and complex media for the rapid detection of fluorescence of phytopathogenic pseudomonads: Effect of the carbon source. Papers in Plant Pathology, 15, 1523–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, S. , Kasai, H. , Arnold, D. L. , Jackson, R. W. , Vivian, A. , & Harayama, S. (2000). Phylogeny of the genus Pseudomonas: Intrageneric structure reconstructed from the nucleotide sequences of gyrB and rpoD genes. Microbiology, 146, 2385–2394. 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y. , Chen, C. , Ren, Y. , Wang, R. , Zhang, C. , Han, S. , … Wu, M. (2019). Pseudomonas mangrovi sp. nov., isolated from mangrove soil. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 69(2), 377–383. 10.1099/ijsem.0.003141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The GenBank accession numbers for the complete genome of Pseudomonas glycinae MS586T and the full‐length sequence of 16S rDNA are CP014205 and MG692779, respectively. The type strain MS586T was deposited in the ARS Culture Collection, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Peoria, IL, USA (Culture collection 1 accession #NRRL B‐6544: https://nrrl.ncaur.usda.gov/cgi‐bin/usda/prokaryote/report.html?nrrlcodes=B‐65441), and the BCCM/LMG Bacteria Collection, Laboratorium voor Microbiologie, Universiteit Gent, Belgium (Culture collection 2 accession #LMG 30275: https://bccm.belspo.be/catalogues/lmg-strain-details?NUM=30275).