Abstract

Background:

Prolonged use of corticosteroids continues to be the mainstay in management of most proteinuric glomerulopathies, but is limited by extensive side effects. Alternative medications such as adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) have been recently used to treat refractory glomerulopathies and have shown superior outcomes when compared with steroids. However, the clinical responsiveness to ACTH therapy varies considerably with a number of patients exhibiting de novo or acquired resistance. The underlying mechanism remains unknown.

Methods:

A patient with steroid-dependent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) developed severe steroid side effects impacting quality of life and was converted to repository porcine ACTH therapy. Immediate response in the form of remission of nephrotic syndrome was noted followed by relapse in 10 weeks. Suspecting the role of some ACTH-antagonizing factors, the patient’s serum was examined.

Results:

Immunoblot-based antibody assay revealed high titers of de novo IgG antibodies in the patient’s serum that were reactive to the porcine corticotropin with negligible cross-reactivity to human corticotropin. In vitro, in cultured B16 melanoma cells that express abundant melanocortin receptors, addition of the patient’s serum substantially abrogated the porcine corticotropin triggered signaling activity of the melanocortinergic pathway, marked by phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β, thus suggesting a mitigating effect on the biological functionality of porcine corticotropin,

Conclusion:

ACTH is a useful alternative therapeutic modality for refractory proteinuric glomerulopathies like FSGS. However, as quintessential therapeutic biologics, natural ACTH, regardless of purity and origin, is inevitably antigenic and may cause the formation of neutralizing antibodies in some sensitive patients, followed by resistance to ACTH therapy. It is imperative to develop ACTH analogues with less immunogenicity for improving its responsiveness in patients with glomerular diseases.

Keywords: corticotropin, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, proteinuria, neutralizing antibody

Background

Treatment of relapsing nephrotic syndrome is challenging despite the advent of newer immunosuppressive medications. Prolonged use of glucocorticoids continues to be the mainstay in management of proteinuric glomerulopathies. The extensive side-effect profile of glucocorticoids limits their use for prolonged therapy. Alternative medications such as animal derived adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) have been recently used in pediatric and adult patients to treat resistant diseases, such as minimal change disease (MCD), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) and others. ACTH has shown to induce remission of nephrotic syndrome not amenable to steroids and other immunosuppression medications. A multicenter small randomized controlled trial in patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy demonstrated superior outcomes with ACTH when compared with the standard Ponticelli regimen[1]. It is hypothesized that the anti-proteinuric action of ACTH is not solely attributed to its steroidogenic effects, because a number of case series studies found that patients with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome still respond well to ACTH therapy[2]. Increasing evidence suggests that ACTH may exert a glomerular protective and antiproteinuric effect via multipronged mechanisms, including direct podocyte protection, lipid lowering action and potent melanocortinergic activities[3].

The clinical responsiveness to ACTH therapy varies, however, considerably with a number of patients exhibiting resistance to treatment [4, 5]. For instance, in a study in patients with idiopathic FSGS, only 7 out of 24 patients responded to ACTH therapy and achieved clinical remission [4]. In another study to determine the effectiveness of ACTH therapy in idiopathic membranous nephropathy, 8 out of 20 patients failed to achieve proteinuria remission after ACTH gel treatment for 1 year [5]. The underlying mechanism remains unknown. As quintessential therapeutic biologics, animal-derived natural ACTH, similar to other biologics like insulin and erythropoietin, regardless of purity and origin, is inevitably antigenic, and thus may have drawbacks like treatment resistance[6]. Antibody development against therapeutic animal-derived ACTH has been reported decades ago in patients with rheumatologic disorders[7-9]. Lately, with the renaissance of ACTH therapy in proteinuric glomerulopathies, de novo formation of antibodies against short-acting ACTH of mixed bovine, ovine, and porcine origins has been noted in a pediatric patient[10]. Here, we present the first proof of concept to measure antibodies against long-acting porcine ACTH in an adult patient after initial complete remission.

Case Description

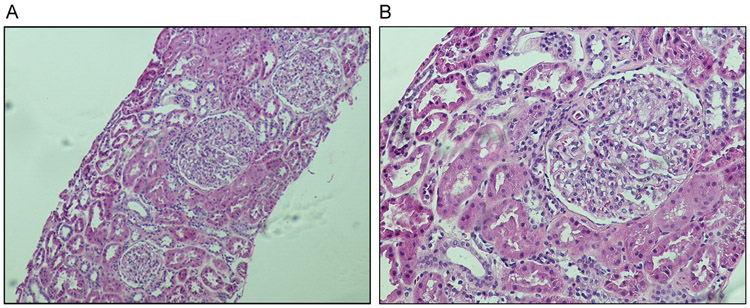

A 25-year-old woman of Asian origin was followed at the Nephrology Clinic of the University of Toledo Medical Center for the management of her nephrotic syndrome. She initially presented with symptoms of foamy urine, fatigue and lower extremity swelling at the age of 17 years. Laboratory evaluation showed proteinuria of 5 g/24h and urine analysis was positive for proteinuria, hematuria and no casts were noted. She underwent renal biopsy that showed MCD and early signs of FSGS. (Figure 1A and 1B).

Figure 1. Histology of kidney biopsy.

The patient’s kidney biopsy specimens were processed for routine periodic acid-Schiff staining. (A) Low power view shows glomerular size variability suggesting glomerulomegaly, a possibly early sign of FSGS, with otherwise normal appearance. (B) High power view shows near normal morphology of glomerulus.

At the time of presentation and throughout the disease course, her renal function was preserved as evaluated by the measurement of serum creatinine and by estimated glomerular filtration rate. She had been normotensive with blood pressure readings in the range of 120/60 mmHg and no other significant personal or family medical history.

She was initially treated with high dose (1mg/kg) of oral prednisone, ensued by regression of proteinuria. Due to frequent relapses of proteinuria and swelling, she received long-term maintenance therapy with daily 15mg of oral prednisone, 50 mg twice a day of cyclosporine and 15mg per day of lisinopril.

The patient responded well to this regimen for approximately three years, but started noticing substantial adverse effects, including elevated blood pressure and blood glucose levels, truncal obesity, menstrual abnormalities, acne and emotional lability. Dose of glucocorticoid was thus tapered with re-appearance of nephrotic range proteinuria.

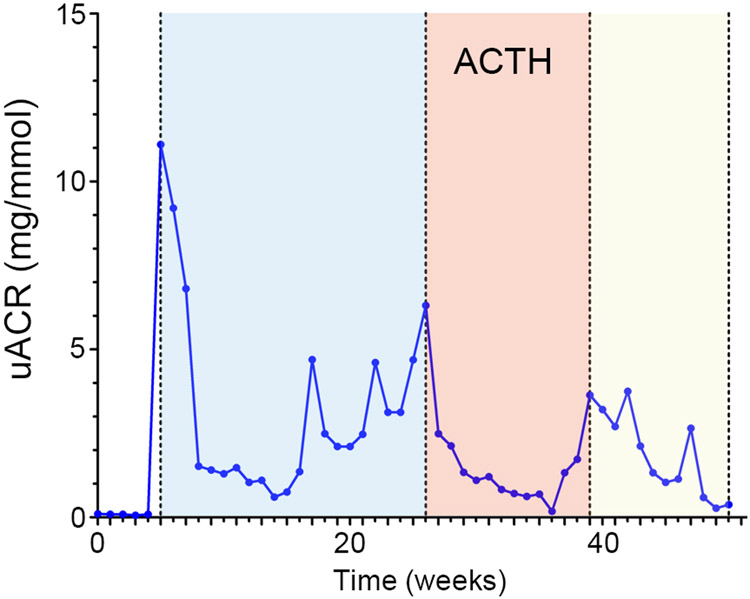

She was offered treatment with repository corticotropin of porcine origin (Acthar gel). Treatment regimen of 40 IU ACTH gel as a subcutaneous injection, twice a week, was initiated and her cyclosporine and lisinopril medications were continued in prior dosage. She developed significant remission in proteinuria, regression of swelling, better blood glucose and generalized feeling of wellbeing on the ACTH gel treatment. Complete remission of proteinuria was noted for about 10 weeks on ACTH, (Figure 2), after which proteinuria and anasarca re-appeared, and she was re-started on high dose of glucocorticoid.

Figure 2. Time course of the patient’s urinary albumin excretion in response to ACTH therapy.

Urinary albumin to creatinine ratios (uACR) at indicated times were collected and plotted. The period of ACTH therapy was colored beige.

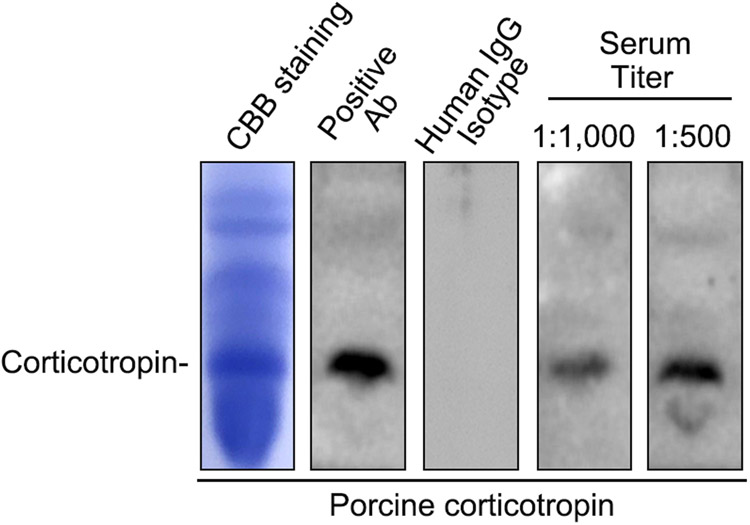

At this time, blood was drawn for immunoblot-based antibody assay for detecting the possible development of ACTH antibody. Abundant anti-ACTH antibody was noted in the patient’s serum (Figure 3). Disease relapse was subsequently treated with Rituximab, to which the patient responded completely with disappearance of proteinuria.

Figure 3. Immunoblot-based antibody assay reveals the formation of ACTH antibodies in the patient’s serum.

Standard porcine corticotropin was fractionated on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels, followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining (leftist panel). Standard porcine corticotropin was fractionated on SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to PVDF membrane, and subjected to immunoblotting overnight with a commercial rabbit anticorticotropin antibody (Ab) as positive control, control human IgG as negative control, or with the patient’s sera (1:500 and 1:1,000 dilution). The blots were then developed by using an anti-rabbit secondary antibody or anti-human IgG antibody. Bands for corticotropin were indicated.

Methods and Results

The patient’s blood was collected 3 weeks after relapse of proteinuria, while she was being treated with ACTH gel. Serum was separated and subjected to immunoblot assay as previously described. Standard porcine corticotropin was fractionated on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Subsequently, the membrane was subjected to blocking with Tris-buffered saline containing 5% bovine serum albumin, and then incubated overnight with either a commercial rabbit anticorticotropin antibody as positive control or with the patient’s serum (1:1,000 or 1:500 dilution). Afterwards, the blots were incubated with an anti-rabbit secondary antibody or anti-human IgG antibody. Finally, the blots were washed three times with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and developed with the Enhanced Chemiluminescence Western Blotting Detection System (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. As a negative control, immunoblots were probed by standard human IgG isotype controls and no bands demonstrated. In stark contrast, immunoblots developed by using the patient’s serum evidently revealed abundant IgG antibodies that were reactive to a peptide band also probed by the anti-ACTH positive control antibody, suggesting that the patient has high titers of circulating anti-ACTH antibodies. To further ascertain if the anti- ACTH antibody in the patient’s serum actually affects the biological functionality of porcine corticotropin, an in vitro test was carried out in B16 melanoma cells, known to express abundant melanocortin receptors. Shown in Supplementary Figure 1, B16 cells were exposed to porcine corticotropin (100 mIU/ml) in the presence or absence of the patient’s serum. Porcine corticotropin treatment apparently triggered the melanocortinergic signaling pathway, as evidenced by an increased phosphorylation of GSK3β, a downstream signaling transducer of the melanocortin cascade. This effect was substantially abrogated by addition of the patient’s serum, suggesting that the anti-ACTH antibody in the patient’s serum is effective in counteracting the biological effect of porcine corticotropin.

Intriguingly, the ACTH antibodies was not associated with any clinical signs of hypoadrenocorticism, or other notable side effects except a delayed-onset resistance to ACTH therapy, entailing that these antibodies are likely specific for porcine ACTH and have negligible cross-reactivity with the patient’s native ACTH. This was validated by a separate immunoblot-based antibody assay to verify the specificity of the anti-ACTH antibody in the patient’s serum. Shown in Supplementary Figure 2, human ACTH was fractionated by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining or by immunoblot analysis through incubating the blots overnight with a commercial rabbit anti-human ACTH antibody as positive control or with the patient’s serum. The blots were then developed by using an anti-rabbit secondary antibody or anti-human IgG antibody. Despite a clear detection of the human corticotropin by the positive control antibody, no bands were detected by the patient’s serum at multiple titers, suggesting that the anti-ACTH antibody in the patient’s serum is unlikely reactive to human ACTH.

Discussion

Corticotropin or ACTH has been successfully used in the treatment of nephrotic syndrome since 1950s. In the past, it was believed that the antiproteinuric effect of ACTH may be attributed to its steroidogenic activity through a direct action on the melanocortin 2 receptor[11, 3] on the adrenal cortex. However, recently more and more studies suggest that ACTH is still quite effective in patients with steroid-resistant glomerular diseases, denoting a steroidogenic-independent proteinurea-reducing activity of ACTH[2], In consistency, a growing body of evidence suggests that non-steroidogenic melanocortin receptors like MC1R and MC5R are expressed by glomerular podocytes and that the melanocortinergic activity of ACTH conveyed by these melanocortin receptors may contribute to a podocyte protective and antiproteinuric action[12-15, 3].

Structurally, ACTH is a 39 amino acid straight chain polypeptide. It is constituted of the highly conserved N-terminal amino acids 1-24, and the C-terminal amino acids 25-39[3]. The first 24 amino acid chain is identical in ACTH derived from all species[10] including human and porcine ACTH. In contrast, the C-terminal amino acids 25-39 of ACTH are species specific and are implicated in antigenicity of the ACTH molecule[16, 17]. ACTH in the formulation used in our patient is naturally occurring porcine ACTH extracted from porcine pituitary[18] and thus is the complete 39 amino acid chain containing the species-specific 25-39 segment of ACTH. Gelatin in the ACTH gel is a commonly used carrier and unlikely antigenic.

As is common with any biologic medications[6] like insulin or erythropoietin, animal-derived ACTH is antigenic to humans, and antibody formation results in resistance to ACTH therapy[19, 20]. Even though biologic preparations of porcine origin are thought to be least antigenic, antibodies to ACTH have been well documented in patients with rheumatologic disorders treated by naturally occurring porcine ACTH[7-9]. Most frequently, anti-porcine IgG has been demonstrated against the C- terminal of the polypeptide chain of ACTH, however there are isolated reports of antibody development to the entire polypeptide chain[16]. There is a case report of antibody formation against short-acting ACTH[10], in which a pediatric patient with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome due to MCD was converted to ACTH therapy after developing Cushing syndrome and severe cellulitis. Following a rapid remission of proteinuria, the patient exhibited a delayed-onset resistance to ACTH treatment, concomitant with de novo antibody formation against ACTH. This unusual finding was attributed to the fact that the short-acting ACTH used in this patient was a mixture of pituitary extracts of porcine, bovine, and ovine origins that greatly rendered it antigenic. In consistency, Glass et al[8, 9] have reported that administration of porcine ACTH induces only humoral immunity but no cellular component as noted by lack of lymphocyte transformation, however data in this regard is limited.

In our report, the possibility of antibody reaction to gelatin carrier of the ACTH gel was rejected, as the serum of our patient was strongly reactive to external standard porcine ACTH. We did not come across any similar case report in our extensive literature search, where initial sustained complete remission of proteinuria induced by ACTH gel treatment was followed by resistance due to antibody development in an adult patient.

Conclusion

ACTH is an alternative therapeutic modality for refractory proteinuric glomerulopathies like FSGS. However, as quintessential therapeutic biologics, natural ACTH, regardless of purity and origin, is inevitably antigenic in humans and may cause the formation of neutralizing antibodies in some sensitive patients, ensued by resistance to ACTH therapy. Our findings stress the need to develop ACTH analogues with less immunogenicity for improving its responsiveness in patients with glomerular diseases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the U.S. National Institutes of Health grant DK092485 and DK114006.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

Drs. Gong and Dworkin report research funding from the Mallincrodt Pharmaceuticals, which is not related to this study. Dr. Gong served as a consultant to the Questcor Pharmaceuticals and the Mallincrodt Pharmaceuticals. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ponticelli C, Passerini P, Salvadori M, Manno C, Viola BF, Pasquali S, et al. A randomized pilot trial comparing methylprednisolone plus a cytotoxic agent versus synthetic adrenocorticotropic hormone in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2006. February;47(2):233–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gong R. The renaissance of corticotropin therapy in proteinuric nephropathies. Nature reviews Nephrology. 2011. December 6;8(2):122–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gong R. Leveraging melanocortin pathways to treat glomerular diseases. Advances in chronic kidney disease. 2014. March;21(2):134–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogan J, Bomback AS, Mehta K, Canetta PA, Rao MK, Appel GB, et al. Treatment of idiopathic FSGS with adrenocorticotropic hormone gel. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2013. December;8(12):2072–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hladunewich MA, Cattran D, Beck LH, Odutayo A, Sethi S, Ayalon R, et al. A pilot study to determine the dose and effectiveness of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (H.P. Acthar(R) Gel) in nephrotic syndrome due to idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2014. August;29(8):1570–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garces S, Demengeot J. The Immunogenicity of Biologic Therapies. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2018;53:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landon J, Friedman M, Greenwood FC. Antibodies to corticotrophin and their relation to adrenal function in children receiving corticotrophin therapy. Lancet (London, England). 1967. March 25;1(7491):652–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass D, Daly JR. Development of antibodies during long-term therapy with corticotrophin in rheumatoid arthritis. I. Porcine ACTH. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 1971. November;30(6):589–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glass D, Nuki G, Daly JR. Development of antibodies during long-term therapy with corticotrophin in rheumatoid arthritis. II. Zinc tetracosactrin (Depot Synacthen). Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 1971. November;30(6):593–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang P, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Brem AS, Liu Z, Gong R. Acquired Resistance to Corticotropin Therapy in Nephrotic Syndrome: Role of De Novo Neutralizing Antibody. Pediatrics. 2017. July;140(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dores RM. Adrenocorticotropic hormone, melanocyte-stimulating hormone, and the melanocortin receptors: revisiting the work of Robert Schwyzer: a thirty-year retrospective. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009. April;1163:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chhajlani V Distribution of cDNA for melanocortin receptor subtypes in human tissues. Biochemistry and molecular biology international. 1996. February;38(1):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voisey J, Carroll L, van Daal A. Melanocortins and their receptors and antagonists. Current drug targets. 2003. October;4(7):586–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cone RD. Studies on the physiological functions of the melanocortin system. Endocrine reviews. 2006. December;27(7):736–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez E, Rubio VC, Cerda-Reverter JM. Characterization of the sea bass melanocortin 5 receptor: a putative role in hepatic lipid metabolism. The Journal of experimental biology. 2009. December;212(Pt 23):3901–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleischer N, Abe K, Liddle GW, Orth DN, Nicholson WE. ACTH antibodies in patients receiving depot porcine ACTH to hasten recovery from pituitary-adrenal suppression. J Clin Invest. 1967. February;46(2):196–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imura H, Sparks LL, Tosaka M, Hane S, Grodsky GM, Forsham PH. Immunologic studies of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH): effect of carboxypeptidase digestion on biologic and immunologic activities. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1967. January;27(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gettig J, Cummings JP, Matuszewski K. H.p. Acthar gel and cosyntropin review: clinical and financial implications. P T. 2009. May;34(5):250–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg AS. Immunogenicity of biological therapeutics: a hierarchy of concerns. Developments in biologicals. 2003;112:15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schellekens H. The immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins. Discovery medicine. 2010. June;9(49):560–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.