Abstract

Background and aims:

In this analysis, we estimated population-level trajectory groups of life course cardiovascular risk to explore their impact on mid-life atherosclerotic and metabolic outcomes.

Methods:

This prospective study followed n=1,269 Bogalusa Heart participants, each with at least 4 study visits from childhood in 1973 through adulthood in 2016. We used discrete mixture modeling to determine trajectories of cardiovascular risk percentiles from childhood to adulthood. Outcomes included mid-life subclinical atherosclerotic measures [(carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT), pulse wave velocity (PWV)], metabolic indicators [(diabetes and body mass index (BMI)], and short physical performance battery (SPPB).

Results:

Between the mean ages of 9.6–48.3 years, we estimated five distinct trajectory groups of life course cardiovascular risk (High-Low, High-High, Mid-Low, Low-Low, and Low-High). Adult metabolic and vascular outcomes were significantly determined by life course cardiovascular risk trajectory groups (all p<0.01). Those in the High-Low group had lower risks of diabetes (20% vs. 28%, respectively; p=.12) and lower BMIs (32.4 kg/m2 vs. 34.6 kg/m2; p=0.06) than those who remained at high risk (High-High) throughout life. However, the High-Low group had better cIMT (0.89 mm vs. 1.05 mm; p<.0001) and PWV (7.8 m/s vs. 8.2 m/s; p=0.03) than the High-High group. For all outcomes, those in the Low-Low group fared best.

Conclusions:

We found considerable movement between low- and high- relative cardiovascular risk strata over the life course. Children who improved their relative cardiovascular risk over the life course achieved better mid-life atherosclerotic health despite maintaining relatively poor metabolic health through adulthood.

Introduction

It is generally accepted that adult cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors are also applicable as indicators of cardiometabolic health among children, with tracking and clustering of these risk factors over time such that adverse CVD profiles in childhood are associated with similarly worse CVD profiles during young adulthood1,2. In early adulthood, however, the risk of future cardiovascular disease (CVD) is up to 95% modifiable through enactment of preventive measures including maintaining a healthy diet, getting adequate exercise, and avoiding the use of tobacco products3. With this understanding in mind, there is good reason to believe that most of the excess future risk of CVD among children with adverse risk profiles can be prevented. In fact, we recently found strong evidence for this hypothesis by documenting high levels of cardiovascular risk mobility (CRM) in a large bi-racial cohort followed for over 40 years4. Briefly, we showed that there was ample opportunity to improve one’s cardiovascular risk ranking relative to one’s peers over the life course (which we termed “CRM” to make it conceptually analogous to socioeconomic mobility or the “American Dream”). In other words, adults’ cardiovascular risk percentile rankings were not heavily influenced by their childhood CVD percentile ranking; individuals’ childhood rankings explained less than five percent of the variation in their adult rankings.

Nevertheless, finding sub-groups of mobility in life course CVD risk could give important insight about which children successfully modify (and which fail to modify) their CVD risk over time, and, more importantly, the resultant effects on health outcomes. Here, we sought to meaningfully magnify our prior work by finding trajectory groups of CRM to examine how individuals’ CRM affects mid-life cardiometabolic health outcomes, including subclinical measures of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease such as carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) and aortic-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV).

Patients and methods

Study population

The Bogalusa Heart Study (BHS) is a series of long-term studies in a semirural biracial (65% white and 35% black) community in Bogalusa, Louisiana, begun in 1973 by Dr. Gerald Berenson, focusing on the early natural history of cardiovascular disease since childhood. For these analyses, all participants of BHS with at least one childhood (age≤18) baseline assessment and one additional follow-up visit (n=7,624) were included, encompassing the years from 1973–2016. Within BHS, the longitudinal collection methods of cardiovascular risk factors, including biomarkers, have been previously described in great detail5. Additional demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle information collected at each study visit (approximately every 2 years) included age, race, sex, height, weight, smoking history, and educational attainment. The BHS is IRB approved by Tulane University and all participants have given informed consent.

Cardiovascular risk percentile ranking

Framingham 10-year risk of coronary heart disease6 was used to rank adult cardiovascular risk. To calculate childhood cardiovascular risk, we used a z-score from age- and sex- standardized residuals of the same risk factors included in the Framingham study (HDL-C, hypertension, systolic blood pressure, smoking, and total cholesterol), resulting in a useful approximation of childhood CVD burden that we have previously utilized and discussed4. The residuals from each of these separate risk factor models were summed to form the continuous z-score for each child7. After calculation of z-scores, participants were ranked according to their percentiles of z-score (0=highest risk factor burden; 100=lowest risk factor burden).

Metabolic and atherosclerotic/vascular outcomes

Using measurements from the same follow-up visit in which adult cardiovascular risk was calculated, we assessed two metabolic (diabetes, body mass index) and three atherosclerotic/vascular [cIMT, PWV, physical performance] outcomes. Although physical performance is itself a useful outcome as a marker of aging, it can also serve as a meaningful proxy for vascular function8. For this study, a person was considered to have diabetes at follow-up if they had a fasting plasma glucose≥126 mg/dL, a self-reported diagnosis of diabetes, or were currently taking medication for diabetes. Body mass index was computed as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared from repeated height and weight measurements (one measurement each by two separate observers) at the follow-up visit. To measure cIMT, we used Toshiba Ultrasound equipment (Toshiba Aplio), and reported the mean cIMT across six measurement locations: left carotid bulb (or bifurcation), left common carotid, left internal carotid, right carotid bulb, right common carotid, and right internal carotid. PWV was averaged from duplicate measures, with a reported coefficient of 0.91 for same-day reliability9. Physical performance was assessed using the Short Physical Performance Battery10 (SPPB), a composite score of gait speed, balance, and leg strength, with a score of less than 10 out of 12 considered “poor physical performance”.

Statistical analysis

To create the trajectories of life course CRM, we used the population of n=1,288 participants with recent measurement of each outcome collected in the 2013–2016 examination. Further, because the trajectory approach requires at least three unique time points and becomes more precise with additional time points, we restricted our analyses to include participants with ≥4 study visits (n=1,269). Therefore, in addition to childhood (baseline) and adult (final follow-up) CVD percentile rankings, we calculated the additional percentile rankings for each of the two additional visits using the same z-score and percentile ranking methods described in the previous paragraph.

Inverse probability of censorship weighting

An Inverse Probability of Censorship Weighting (IPCW) approach was used to correct for bias from loss to follow-up11. Briefly, we made an indicator variable for loss to follow-up among all 7,624 participants in order to identify those with baseline data who did not contribute to the final follow-up visit. A multivariable logistic regression model was then formed with this indicator variable as the dependent variable (1=remained in study; 0=lost to follow-up). Independent variables in this model were age, sex, race, BMI, total cholesterol, triglycerides, number of visits prior to loss to follow-up, and year of enrollment. The predicted probabilities (p) from this model represented the probability of remaining in the study, and the IPC weights were calculated as: 1/p. The distribution of these weights was examined to determine whether there were participants with extreme influence (i.e. very large weight values), although we chose not to remove nor trim outlier weights given that model specification was very good12. Model performance was assessed using Pearson’s goodness-of-fit test and the c-statistic.

Trajectory analysis

We applied discrete mixture modeling (using SAS Proc TRAJ13) to estimate distinct trajectories of individual CRM from childhood to adulthood. These distinct trajectory groups were then compared regarding subsequent mid-life outcomes (physical performance, cIMT, PWV, diabetes, and BMI).

First, the distinct CRM trajectory groups were formed using Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) to determine the best number of distinct groups, where: BIC=log(likelihood)-0.5*log(sample size)*number of parameters. We tested models using 3–9 distinct groups and selected the model with the lowest absolute BIC value. Demographic and health characteristics of the final CRM trajectory groupings were tabulated and compared using Pearson’s chi-squared tests (categorical variables) or analysis of variance (ANOVA) (continuous variables).

After the CRM trajectory groups were selected, they were labeled according to relative childhood and adult CVD risk (high, medium, or low). When further characterizing these groups in terms of mobility, positive mobility describes an increase in CVD risk percentile ranking across the life course (i.e. moving from high childhood CVD risk to low adult CVD risk), whereas negative mobility indicates a decrease in CVD risk percentile ranking. Once the CRM trajectory groups were described and compared, these groups formed the independent variable in two separate logistic regression models to assess the effect of CRM trajectories on: 1.) physical performance; and 2.) diabetes; as well as three separate linear regression models for: 3.) BMI; 4.) cIMT; and 5.) PWV; with adjustment for age, race, sex, follow-up time, smoking status, and educational attainment (completed high school = yes/no). In addition to these covariates, we included the group-membership probabilities as an independent variable in each of these models to account for the uncertainty in trajectory groupings14. For the two logistic regression models, the overall p-value for a trend across groups was reported, along with pairwise multiple comparisons between all groups using Bonferroni-corrected confidence intervals and p-values. For the three linear regression models, we reported the overall p-value for a trend across groups, as well as the Tukey-Kramer-corrected pairwise comparisons between all groups.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of n=1,269 participants contributed 49,027 person-years of follow-up time [mean(SD)=38.6(3.5)]. Each participant contributed to this analysis at exactly four time points (mean ages = 9.6, 12.6, 16.5, and 48.3).

From the SAS Proc TRAJ discrete mixture modeling macro, we selected the model with 5 trajectory groups. Each of the 5 groups was significantly unique from the others at the p<.0001 level, and the percentage of participants in each group ranged from 15.1%−25.7% (Figure 1). Specific characteristics of each of the five groups are given in Table 1. The mean predicted probabilities of group membership within each group ranged from 59% (Mid-Low) to 79% (Low-Low), indicating the trajectory model adequately assigned participants into each group.

Figure 1:

Five distinct trajectories of life course cardiovascular risk Five life course trajectory groups of cardiovascular risk mobility. The thick, solid lines are group means, with the thinner dashed lines indicating each group’s 95% confidence interval

Table 1:

Characteristics of the five distinct trajectory groups of cardiovascular risk percentile ranking

| Demographics: | High-Low (n=192, 15.1%) | High-High (n=326, 25.7%) | Mid-Low (n=246, 19.4%) | Low-Low (n=272, 21.4%) | Low-High (n=233 18.4%) | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | <.0001 | ||||||

| Female, n(%) | 178 (92.7%) | 91 (27.9%) | 201 (81.7%) | 224 (82.4%) | 62 (26.6%) | ||

| Male, n(%) | 14 (7.3%) | 235 (72.1%) | 45 (18.3%) | 48 (17.6%) | 171 (73.4%) | ||

| Race | 0.33 | ||||||

| White | 132 (68.8%) | 220 (67.5%) | 155 (63.0%) | 168 (67.8%) | 159 (68.2%) | ||

| Black | 60 (31.2%) | 106 (32.5%) | 91 (37.0%) | 104 (38.2%) | 74 (31.8%) | ||

| Baseline: | |||||||

| Age, mean(SD) | 9.4 (3.3) | 9.5 (3.3) | 9.5 (3.2) | 10.0 (3.6) | 9.4 (3.0) | 0.27 | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean(SD) | 18.9 (4.6) | 18.3 (3.7) | 17.4 (3.5) | 16.8 (2.8) | 16.6 (2.6) | <.0001 | |

| BMI percentileb, median(IQR) | 60 (32, 88) | 54 (29, 78) | 51 (23, 74) | 41 (20, 66) | 45 (24, 66) | <.0001 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), mean(SD) | 104 (10.4) | 104 (8.7) | 100 (9.6) | 95 (9.2) | 95 (7.8) | <.0001 | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL), mean(SD) | 176 (27) | 173 (28) | 162 (27) | 154 (27) | 153 (24) | <.0001 | |

| HDL-C (mg/dL), mean(SD) | 57 (23) | 63 (20) | 65 (19) | 71 (21) | 69 (18) | <.0001 | |

| LDL-C (mg/dL), mean(SD) | 107 (25) | 101 (23) | 88 (20) | 77 (18) | 78 (16) | <.0001 | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL), median(IQR)* | 75 (56, 99) | 68 (51, 88) | 62 (46, 82) | 55 (44, 74) | 51 (41, 68) | <.0001 | |

| Current smoker (≥1 cigarette/week) | 6 (3.1%) | 12 (3.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | <.0001 | |

| CVD risk percentile ranking, median(IQR) | 22 (9, 36) | 25 (14, 40) | 49 (32, 64) | 80 (65, 90) | 73 (59, 87) | <.0001 | |

| Follow-up: | |||||||

| Age, mean(SD) | 46.8 (5.6) | 48.2 (5.0) | 48.0 (5.4) | 48.7 (5.4) | 49.0 (5.3) | <.0001 | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean(SD) | 34.4 (9.6) | 32.2 (7.5) | 31.1 (7.5) | 29.9 (7.4) | 30.2 (6.6) | <.0001 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), mean(SD) | 119 (15) | 131 (18) | 118 (15) | 119 (17) | 128 (16) | <.0001 | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL), mean(SD) | 190 (34) | 209 (47) | 188 (36) | 180 (35) | 191 (39) | <.0001 | |

| HDL-C (mg/dL), mean(SD) | 54 (16) | 44 (14) | 55 (14) | 59 (18) | 47 (18) | <.0001 | |

| LDL-C (mg/dL), mean(SD) | 111 (31) | 131 (40) | 111 (31) | 101 (30) | 116 (36) | <.0001 | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL), median(IQR)* | 108 (79, 152) | 142 (102, 207) | 100 (70, 133) | 87 (67, 122) | 114 (88, 171) | <.0001 | |

| Current smoker (≥1 cigarette/week) | 21 (10.9%) | 156 (47.9%) | 31 (12.6%) | 29 (10.7%) | 109 (46.8%) | <.0001 | |

| Completed high school | 168 (87.5%) | 267 (81.9%) | 229 (93.1%) | 239 (87.9%) | 190 (81.6%) | <.001 | |

| Years of follow-up, mean(SD) | 37.3 (4.1) | 38.7 (3.3) | 38.5 (3.6) | 38.7 (3.4) | 39.6 (2.6) | <.0001 | |

| CVD risk percentile ranking, median (IQR) | 66 (56, 78) | 18 (8, 32) | 62 (48, 76) | 66 (50, 80) | 22 (12, 32) | <.0001 | |

| Change in CVD risk percentile ranking, median(SD) | +42 (29, 57) | −8 (−23, +5) | +13 (−7, +31) | −12 (−32, +11) | −51 (−63, −33) | <.0001 | |

ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-squared for categorical variables;

Sex- and age-standardized percentiles of BMI are presented

Metabolic outcomes

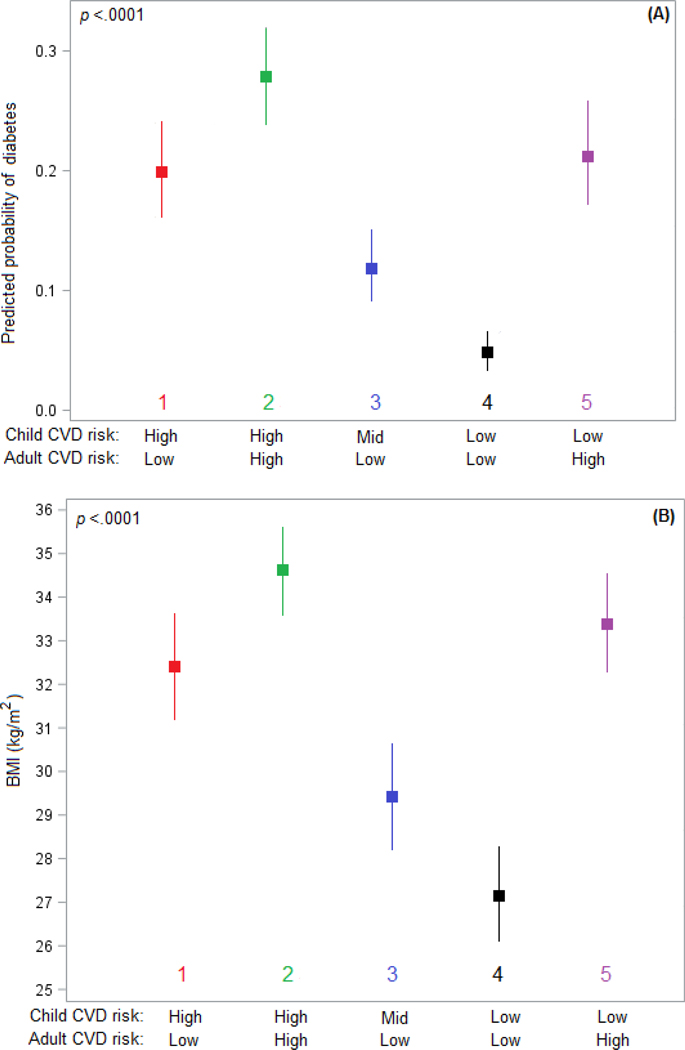

In our cohort, 226 (17.8%) participants had diabetes at their adult follow-up and mean (SD) BMI at adult follow-up was 31.5 (7.8) kg/m2 (Table 2). After multivariable adjustment, adult metabolic outcomes (diabetes and BMI) were significantly influenced by CRM trajectory groups (both p<.0001). Between trajectory groups, the largest differences were seen between the High-High and Low-Low groups, with High-High having much greater risk of diabetes (OR=7.78; 95% CI: 4.23, 14.3; p<.0001) and a greater BMI (+6.3 kg/m2; 95% CI: 4.0, 8.5; p<.0001) than Low-Low. Those with a High-Low trajectory had a similar risk of diabetes (OR=0.92; 95% CI: 0.53, 1.59; p=0.99) and similar BMI (−1.1 kg/m2; 95% CI: −3.5, +1.3; p=0.75) compared to those in the Low-High trajectory. All adjusted pairwise comparisons between trajectory groups for diabetes and BMI are given in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Figure 2 shows plots of adjusted probability of diabetes and adjusted BMI, respectively.

Table 2:

Unadjusted metabolic and vascular outcomes by CRM Trajectory Group

| Outcomes: | ALL (n=1,269) | High-Low 192 (15.1%) | High-High 326 (25.7%) | Mid-Low 246 (19.4%) | Low-Low 272 (21.4%) | Low-High 233 (18.4%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes, n (%) | 226 (17.8%) | 39 (20.3%) | 75 (23.0%) | 45 (18.3%) | 27 (9.9%) | 40 (17.2%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.5 (7.8) | 34.4 (9.6) | 32.2 (7.5) | 31.1 (7.5) | 29.9 (7.4) | 30.2 (6.6) |

| Low SPPBa, n(%) | 257 (20.3%) | 31 (16.1%) | 76 (23.3%) | 56 (22.8%) | 42 (15.4%) | 52 (22.3%) |

| cIMT (mm) | 0.95 (0.33) | 0.85 (0.29) | 1.07 (0.37) | 0.88 (0.27) | 0.87 (0.27) | 1.01 (0.33) |

| PWV (m/s) | 7.98 (1.37) | 7.84 (1.22) | 8.35 (1.55) | 7.68 (1.24) | 7.70 (1.35) | 8.24 (1.19) |

Low SPPB defined as a score of <10 out of 12 on the Short Physical Performance Battery assessment used as our dichotomous indicator of poor physical performance

Figure 2:

Adjusted adult metabolic outcomes by life course cardiovascular risk trajectory group Adjusted probability of diabetes (A) and adjusted mean BMI (B) at adult follow-up for each of the five life course trajectory groups of cardiovascular risk mobility with adjustment for age, race, sex, follow-up time, smoking status, and educational attainment (completed high school =yes/no).

Atherosclerotic/physical performance outcomes

Mean (SD) cIMT was 0.95 (0.33) mm, mean (SD) PWV was 7.98 (1.4) m/s 257 (20.3%) individuals had poor physical performance. Similarly, adult vascular outcomes (physical performance, cIMT, and PWV) were significantly influenced by CRM trajectory groups (all three p<.01) after multivariable adjustment. Between trajectory groups, the largest differences were again seen between the High-High and the Low-Low groups, with High-High having much greater risk of poor physical performance (OR=1.96; 95% CI: 1.22, 3.14; p<.001), a greater cIMT (+0.20 mm; 95% CI: +0.13, +0.28; p<.0001), and a faster PWV (+0.63 m/s 95%CI: 0.32, 0.94; p<.0001) than Low-Low. Those with a High-Low trajectory had a similar risk of poor physical performance (OR=0.94; 95% CI: 0.57, 1.56; p=0.99), but exhibited a slower PWV (−0.39 m/s; 95% CI: −0.75, −0.03; p=0.03) and lower cIMT (−0.08 m/s; 95% CI: −0.17, +0.00; p=0.07) than those with a Low-High trajectory. All adjusted pairwise comparisons between trajectory groups for physical performance, cIMT, and PWV are given in Supplementary Tables 3-5. Figure 3 shows the adjusted probability of poor physical performance, adjusted cIMT, and adjusted PWV, respectively by trajectory groups.

Figure 3:

Adjusted adult vascular outcomes by life course cardiovascular risk trajectory group.

Adjusted mean cIMT (C) adjusted mean PWV (D), and adjusted probability of poor physical performance (E) at adult follow-up for each of the five life course trajectory groups of cardiovascular risk mobility, with adjustment for age, race, sex, follow-up time, smoking status, and educational attainment (completed high school =yes/no)

Discussion

Studies examining trajectories of a single CVD risk factor, such as BMI,15,16 systolic blood pressure17,18, or multiple unique cardiovascular risk factors within the same cohort19,20 are becoming increasingly common. To our knowledge, however, ours is the first to examine trajectories of global cardiovascular risk from childhood to adulthood and associate these with clinical and subclinical outcomes, such as diabetes, cIMT and PWV, particularly in a population including a significant proportion of African-Americans. This trajectory analysis builds upon our prior novel research which showed a high level of mobility in life course cardiovascular risk, such that those with high CVD risk relative their peers had ample opportunity to become adults with low risk, and vice versa4. Furthermore, we were able to examine the effects of these trajectories on meaningful clinical and subclinical metabolic and vascular outcomes during adulthood.

Interestingly, our trajectory analysis implied that among those who had CVD risk factor burdens in childhood, positive mobility seemed to limit the progression of atherosclerotic CVD despite doing little to alleviate the risks of obesity, diabetes, and poor physical performance that were largely carried forward into adulthood. This result is generally consistent with the well-documented paradigm that cardiovascular disease forms over the life course from an accumulation of risk, and that the transition during young adulthood from a high-risk childhood to a low-risk status at mid-adulthood may help avoid excess risk accumulation. However, this result also suggests that having a high CVD risk burden as a child may make reductions in metabolic risks less surmountable into adulthood than changes in atherosclerotic CVD risk. Because diabetes, obesity, and poor physical performance are themselves strong predictors of CVD morbidity and mortality, it will be important to follow BHS participants for the next 20+ years to see if the reduced atherosclerotic CVD risk seen in positively mobile participants translates to reductions in hard CVD events despite the high metabolic risk in this group. Among the other trajectory groups, those who maintained a low CVD risk throughout the life course had the best metabolic and vascular outcomes as adults, while those who maintained a high risk throughout the life course had the worst.

The characteristics of our trajectory groups indicated that women were more likely to be in a trajectory group with a low adult CVD risk, with about 80% of all women in the cohort being found in High-Low, Mid-Low, or Low-Low groups versus only approximately 20% of all men in the cohort in these groups. Given that CVD risk is known to be higher for middle aged men, this result is expected21. On the other hand, there were no differences in racial composition across groups; black and white participants were evenly distributed. This implies that race did not differentially impact the distribution of CRM from childhood to adulthood. In Low-High, which had low childhood risk but faced steep negative mobility towards high risk adulthood, a high prevalence of smoking (nearly 50% of the group at follow-up) may largely explain the decline. Likewise, this was also the least educated group with only 81.6% obtaining a high school degree. The low childhood risk factor burden enjoyed by this group did not significantly prevent the later risks of diabetes, poor physical performance, or obesity. However, carotid intima-media thickening was significantly less pronounced in Low-High compared to High-High, which was at a high relative cardiovascular risk throughout the life course, supporting prior autopsy evidence that carotid intima media thickening begins in childhood22.

Several trajectory analyses of BMI have failed to find distinct groups with cross-over trajectories, such as groups with higher relative childhood BMIs that have lower adult BMIs (or the inverse)15,23,24. This is consistent with our analysis; those who started with higher BMIs in childhood generally became adults with high BMIs, regardless of whether they experienced positive, negative, or neutral cardiovascular risk mobility. We have made the important finding, however, that many of those who had consistently high BMIs from childhood through adulthood were better able to avoid carotid intima-media thickening if they experienced positive mobility in cardiovascular risk. Thus, our result is also consistent with the emerging hypothesis that all types of obesity may not be equally associated with subclinical and clinical cardiovascular disease25,26.

As compared to our prior work on showing substantial life course CRM, the current investigation of trajectory groups demonstrated substantial cross-over between trajectory groups of life course global cardiovascular risk. Approximately 18% of the cohort began in the lowest risk group as children and ended with a high adult CVD risk, while 15% started in the highest risk group as children and became adults with low relative CVD risk. This high level of mobility supports our prior findings and makes it reasonable to believe that substantial life course cross-over in relative risk does indeed occur at the levels indicated by our trajectory analysis4. Because CVD risk in relation to one’s peers can increase or decrease drastically over the life course, preventive behavioral and lifestyle approaches should be widely encouraged for all children regardless of their apparent CVD risk burden.

As with BMI, we found that children with high relative CVD risk were largely unable to avoid being at high risk for diabetes or having poor physical performance as adults, regardless of their mobility trajectories. Therefore, despite the lowered risk of adult subclinical CVD among those with positive mobility, children with high risk factor burdens remain an important primary target for prevention of adult metabolic syndrome. Indeed, many studies have documented the tracking of lipids and cholesterol from childhood to adulthood27–29. Our analysis does not imply that individual risk factors do not track. Rather, it highlights that there remains an important distinction between metabolic syndrome and global cardiovascular risk – despite many shared mechanisms, there are key differences in the underlying biology of metabolic disorders, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. This may help explain why screening for subclinical atherosclerotic disease in Type 2 diabetes patients has not proven effective for improving cardiovascular outcomes30.

The High-High and Low-High groups in our study, despite having very similar Framingham scores (median percentile rankings of 18, and 22, respectively), had significant differences in cIMT that could conceivably be used to more accurately differentiate their risks, for example. In fact, cIMT has been shown to add predictive ability for cardiovascular events when added to the Framingham risk factors31, although these studies have generally been conducted in much older populations than our own. Nevertheless, our findings support that cIMT may have additional predictive utility to contribute to adult CVD risk models.

Our study does have some limitations to discuss. Foremost is the loss to follow-up from the original enrollment of the Bogalusa Heart Study, although the IPCW approach was used to limit the potential impact of this emigrative selection bias. A second limitation is the small number of metabolic outcomes we could assess given that total cholesterol and lipoproteins are individually included in the Framingham risk algorithm. As discussed in our prior work4, there is no reliable childhood cardiovascular risk score. Many studies have used z-scores of cardiometabolic risk factors to assess childhood risk in a manner similar to ours7,32. Despite the fact that our measures of childhood and adult risk were calculated using the identical set of risk factors, they differed in their underlying algorithms, which could add an uncertain amount of random error to our results. Nevertheless, the development of a meaningfully predictive childhood cardiovascular risk score remains elusive, and our results are suggestive that this could be due to the large amount of crossover is risk strata over the life course. Because cardiovascular risk is largely modifiable, it will likely remain difficult to predict a child’s cardiovascular risk moving forward. Further, our use of multiple time points did not seem to highlight any clearly-defined periods of increased modifiable over the life course, but rather our trajectories showed that there was relatively consistent mobility in risk strata from childhood through adulthood. Third, although we have adjusted for major confounders, we do not discount the possibility of residual confounding from unmeasured confounders. As this is an observational study, we make no claims of causality, but rather we hoped to elucidate life course associations that could be hypothesis-forming within a complex web of cardiometabolic pathways. While there are very few cardiovascular cohorts with 40+ years of follow-up, our results should be tested among those with the available data to determine whether similar patterns are seen in external populations.

In summary, we have expanded the concept of CRM to show that positive cardiovascular risk trajectories are associated with a better atherosclerotic profile in mid-life, despite the more muted effects of positive CRM on reducing the risks of obesity and diabetes in adulthood. Nearly equal amounts of children move from a high childhood CVD risk burden to low adult CVD risk (High-Low) as from Low-High. These findings provide further support for the proposition that life course cardiovascular risk is very dynamic and not overwhelmingly influenced by childhood CVD risk burden. Those tasked with the clinical care of children should express optimism that even the highest risk children can make great strides towards lowering their adult CVD risk, while simultaneously cautioning low risk children that they must also adopt good preventive behaviors over the life course.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Five distinct trajectories of life course CVD risk were identified

Many children with high CVD relative risk factor burdens became low CVD risk adults

The high → low risk group had healthy carotid IMT and pulse wave velocity as adults

Atherosclerotic health is more modifiable than obesity & diabetes over the lifecourse

Acknowledgments

Financial support

This work was supported by R01 ES021724 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and R01 AG041200 from the National Institute on Aging. This research was also funded in part by The Prize Paper Award from the Michigan State University Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared they do not have anything to disclose regarding conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Katzmarzyk PT, Perusse L, Malina RM, Bergeron J, Despres JP, Bouchard C. Stability of indicators of the metabolic syndrome from childhood and adolescence to young adulthood: the Quebec Family Study. J Clin Epidemiol. February 2001;54(2):190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Celermajer DS, Ayer JGJ. Childhood risk factors for adult cardiovascular disease and primary prevention in childhood. Heart. November 2006;92(11):1701–1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. September 11 2004;364(9438):937–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollock BD, Harville EW, Mills KT, Tang W, Chen W, Bazzano LA. Cardiovascular Risk and the American Dream: Life Course Observations From the BHS (Bogalusa Heart Study). J Am Heart Assoc. February 6 2018;7(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berenson GS, Bogalusa Heart Study I. Bogalusa Heart Study: a long-term community study of a rural biracial (Black/White) population. The American journal of the medical sciences. November 2001;322(5):293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleeman JI, Grundy SM, Becker D, et al. Executive summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Jama-J Am Med Assoc. May 16 2001;285(19):2486–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenmann JC. On the use of a continuous metabolic syndrome score in pediatric research. Cardiovasc Diabetol. June 5 2008;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heffernan KS, Chale A, Hau C, et al. Systemic vascular function is associated with muscular power in older adults. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:386387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen W, Li SX, Fernandez C, et al. Temporal Relationship Between Elevated Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffening Among Middle-Aged Black and White Adults. Am J Epidemiol. April 1 2016;183(7):599–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A Short Physical Performance Battery Assessing Lower-Extremity Function - Association with Self-Reported Disability and Prediction of Mortality and Nursing-Home Admission. J Gerontol. March 1994;49(2):M85–M94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robins JM, Rotnitzky A, Zhao LP. Analysis of Semiparametric Regression-Models for Repeated Outcomes in the Presence of Missing Data. J Am Stat Assoc. March 1995;90(429):106–121. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee BK, Lessler J, Stuart EA. Weight trimming and propensity score weighting. Plos One. March 31 2011;6(3):e18174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones BL, Nagin DS. Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them. Sociol Method Res. May 2007;35(4):542–571. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark SL, Muthén B. (2009). Relating Latent Class Analysis Results to Variables Not Included in the Analysis. Avaliable online at: http://www.statmodel.com/download/relatinglca.pdf.

- 15.Ostbye T, Malhotra R, Landerman LR. Body mass trajectories through adulthood: results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 Cohort (1981–2006). International journal of epidemiology. February 2011;40(1):240–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhana K, van Rosmalen J, Vistisen D, et al. Trajectories of body mass index before the diagnosis of cardiovascular disease: a latent class trajectory analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. June 2016;31(6):583–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen NB, Siddique J, Wilkins JT, et al. Blood pressure trajectories in early adulthood and subclinical atherosclerosis in middle age. Jama. February 05 2014;311(5):490–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hao G, Wang XL, Treiber FA, Harshfield G, Kapuku G, Su SY. Blood Pressure Trajectories From Childhood to Young Adulthood Associated With Cardiovascular Risk Results From the 23-Year Longitudinal Georgia Stress and Heart Study. Hypertension. March 2017;69(3):435-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pletcher MJ, Vittinghoff E, Thanataveerat A, Bibbins-Domingo K, Moran AE. Young Adult Exposure to Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Risk of Events Later in Life: The Framingham Offspring Study. Plos One. May 3 2016;11(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norby FL, Soliman EZ, Chen LY, et al. Trajectories of Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation Over a 25-Year Follow-Up The ARIC Study (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities). Circulation. August 23 2016;134(8):599–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson R, Chambless L, Higgins M, et al. Sex difference in ischemic heart disease mortality and risk factors in 46 communities: an écologie analysis. WHO MONICA Project, and ARIC Study. Cardiovasc Risk Factors. 1997;7:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berenson GS, Srinivasan SR, Bao WH, et al. Association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in children and young adults. New Engl J Med. June 4 1998;338(23):1650–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albrecht SS, Gordon-Larsen P. Ethnic Differences in Body Mass Index Trajectories from Adolescence to Adulthood: A Focus on Hispanic and Asian Subgroups in the United States. Plos One. September 5 2013;8(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elrashidi MY, Jacobson DJ, St Sauver J, et al. Body Mass Index Trajectories and Healthcare Utilization in Young and Middle-aged Adults. Medicine. January 2016;95(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rey-Lopez JP, de Rezende LF, de Sa TH, Stamatakis E. Is the Metabolically Healthy Obesity Phenotype an Irrelevant Artifact for Public Health? Am J Epidemiol. November 1 2015;182(9):737–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stefan N, Haring HU, Hu FB, Schulze MB. Metabolically healthy obesity: epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Lancet Diabetes Endo. October 2013;1(2):152–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauer RM, Clarke WR. Use of Cholesterol Measurements in Childhood for the Prediction of Adult Hypercholesterolemia - the Muscatine Study. Jama-J Am Med Assoc. December 19 1990;264(23):3034–3038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webber LS, Srinivasan SR, Wattigney WA, Berenson GS. Tracking of SerumLipids and Lipoproteins from Childhood to Adulthood - the Bogalusa Heart-Study. Am J Epidemiol. May 1 1991;133(9):884–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Porkka KVK, Viikari JSA, Taimela S, Dahl M, Akerblom HK. Tracking and Predictiveness of Serum-Lipid and Lipoprotein Measurements in Childhood - a 12-Year Follow-up - the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Am J Epidemiol. December 15 1994;140(12):1096–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young LH, Wackers FJ, Chyun DA, et al. Cardiac outcomes after screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: the DIAD study: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. April 15 2009;301(15):1547–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baldassarre D, Hamsten A, Veglia F, et al. Measurements of carotid intima-media thickness and of interadventitia common carotid diameter improve prediction of cardiovascular events: results of the IMPROVE (Carotid Intima Media Thickness [IMT] and IMT-Progression as Predictors of Vascular Events in a High Risk European Population) study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. October 16 2012;60(16):1489–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen LB, Harro M, Sardinha LB, et al. Physical activity and clustered cardiovascular risk in children: a cross-sectional study (The European Youth Heart Study). Lancet. July 22 2006;368(9532):299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.