Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To document sex differences in late-life cognitive function and identify their early-life determinants among older Indian adults.

DESIGN

Harmonized Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia for Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI-DAD).

SETTING

Individual cognitive testing in hospital or household setting across 14 states of India.

PARTICIPANTS

Individuals aged 60 years and older from LASI-DAD (2017–2019) (N = 2,704; 53.5% female).

MEASUREMENTS

Given the low levels of literacy and numeracy among older Indian adults, we consider two composite cognitive scores as outcome variables. Score I is based on tests that do not require literacy or numeracy, whereas score II is based on tests that require such skills. Ordinary least squares is used to estimate models featuring a progressively increasing number of covariates. We add to the baseline specification, including a sex dummy, age, and state indicators, measures of early-life socioeconomic status (SES), early-life nutrition, as proxied by knee height, and education.

RESULTS

Across most cognitive domains, women perform significantly worse than for men: −0.4 standard deviations (SD) for score I and −0.8 SD for score II. Early-life SES, health, and education explain 90% of the gap for score I and 55% for score II. Results are similar across hospital-based and home testing.

CONCLUSION

In India, lower levels of early-life human capital investments in nutrition and education among women compared with men are associated with a female disadvantage in late-life cognitive health. This has important implications for public health policy, aiming at reducing the risk of cognitive decline and dementia—a nascent concern in India.

Keywords: cognition, India, sex

INTRODUCTION

The Alzheimer’s and Related Disorders Society of India1 estimated that about 4 million Indians had dementia in 2010. Given the rapid aging of the Indian population, this number has likely increased substantially in the last decade and may now account for more than 10% of individuals with dementia worldwide.2 Considering the high rate of undiagnosed patients in India,3,4 such an estimate plausibly represents a lower bound of what the actual prevalence of dementia may be among older Indians. Moreover, because of widespread sex-discriminating practices and differential access to formal healthcare services, there exists insufficient evidence about whether dementia prevalence varies by sex and, if so, about what the determinants of observed differences might be. Previous efforts to study dementia and cognition in India have relied on relatively small, nonrepresentative samples in geographically restricted areas.5,6 Although insightful, the findings of these studies have been difficult to generalize to the entire population. At the same time, limited data availability has prevented these initiatives from shedding light on heterogeneity in dementia prevalence across groups and from identifying potential factors underlying it.

Using newly available and rich data from the Longitudinal Aging Study in India–Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia (LASI-DAD), we undertake a comprehensive investigation of sex differences in late-life cognition in India and of their possible determinants. In particular, we focus on the extent to which disparities in early-life socioeconomic conditions, nutrition, and educational achievement explain observed disparities by sex in late-life cognition and quantify their relative contribution.

Prior studies have documented that, compared with their male counterparts, older women are at a significant disadvantage in terms of cognitive ability in developing countries, such as India, China, Indonesia, Latin America, and Egypt,7–12 but less so in developed economies,13–15 where, however, sex differences in the type of dementia have been observed at very old ages. Specifically, although in developed countries there seem to be no significant differences in the overall prevalence of cognitive impairment and dementia by sex,16–18 among individuals older than 80 years, women are at a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease than men, but have the same odds of experiencing vascular dementia.19–21 These patterns can be partly explained by selective survival,22,23 but other lifestyle factors, such as intellectual stimulation, physical activity, and smoking, have also been put forward as possible drivers.24,25

Because education has a strong, protective effect on cognition,26–31 sex disparities in later-life cognition could simply reflect wider gaps in educational attainment between men and women in developing than in developed countries. Childhood nutrition has also been found to be an important correlate of later-life cognition in several countries.32–38 Existing studies examining this association have used birth weight,39–41 leg length, and skull circumference42 to proxy for early-life nutrition. We assess the relative contribution of early-life socioeconomic status (SES) and nutrition, as well as of education, to explain observed sex gaps in late-life cognition in the context of India. This is an interesting setting, where sustained economic growth over the past decades has not translated into population-wide educational expansion among the cohorts surveyed by the LASI-DAD (education became compulsory and free for Indian children aged 6–14 years in 200943), whereas cultural and traditional habits may perpetuate inequality of opportunities by sex.

METHODS

We rely on rich data on cognitive health of Indians aged 60 years and older from the LASI-DAD. The study protocol44 and harmonized data are publicly available. We construct two composite cognition indexes, which we use as dependent variables: score I, which sums scores on all tests that do not require either literacy or numeracy; and score II, which sums scores on all tests that do require literacy or numeracy. Given that rates of illiteracy and innumeracy among older Indians vary significantly by sex, this distinction allows us to examine the sex gap and its potential determinants in more basic cognitive functions and, separately, in cognitive domains where skills, such as reading, writing, and counting, are paramount.

Score I adds the scores on the following cognitive tasks: orientation to time and place, days of week named backwards, object naming, repetition of a phrase, close eyes, paper folding, write (for literate) or say (for illiterate) a sentence, immediate and delayed word recall, word list recognition, immediate and delayed story recall, logical memory recognition, three items from the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status battery, animal naming, four items from the Community Screening Interview for Dementia, Raven’s Progressive Matrices, go-no-go, drawing overlapping pentagons, symbol cancellation, and immediate and delayed constructional praxis. Score II is the sum of three test scores that explicitly require literacy and/or numeracy to be performed, namely, serial 7s, digit span forward and backward, and clock drawing tasks. LASI-DAD provides imputed values for all cognitive test scores, as described in another article in this issue.45 Because our outcome variables are composite scores, we rely on imputed values of test scores to retain the entire sample and to avoid loss of information and corresponding bias stemming from excluding respondents with missing values on single cognitive test scores (our results remain unchanged if we use the subsample of respondents with no missing test scores).

We proxy for early-life SES using parental education and birth location, both obtained from the main LASI. The LASI-DAD assesses participants’ knee height, which we adopt as an indicator of early-life nutrition. The advantage of using knee height over height as a measure of early-life nutrition is that the former is not subject to age-related shrinkage, which may be significant in the LASI-DAD cohort and associated with late-life socioeconomic conditions.46–48 We begin with a total sample of 3,224 LASI-DAD respondents. Of these, 520 (16%) have missing information on one or more covariates. The variables with most missing values are knee height (7%) and parental education (about 5%). After dropping respondents with missing observations on any of the covariates used in the analysis, we are left with a sample of 2,704 individuals, 1,446 women and 1,258 men. A summary of sample characteristics is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary Sample Characteristics

| Women (N = 1,446) |

Men (N = 1,258) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Age, y | ||||

| 60–64 | 0.34 | 0.48 | 0.30 | 0.46 |

| 65–69 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.47 |

| 70–74 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.18 | 0.39 |

| 75–79 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.30 |

| ≥80 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.28 |

| Born in rural area | 0.70 | 0.46 | 0.67 | 0.47 |

| Caste/tribe: | ||||

| Not from disadvantaged caste/tribe | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.47 |

| Scheduled caste | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.38 |

| Scheduled tribe | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.23 |

| Other backward caste | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.50 |

| Religion | ||||

| Hindu | 0.77 | 0.42 | 0.79 | 0.41 |

| Muslim | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.36 |

| Other minorities | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| Mother attended school | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.33 |

| Father attended school | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.30 | 0.46 |

| Knee height, cm | 47.20 | 2.97 | 51.20 | 2.96 |

| Education | ||||

| No school | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.48 |

| Less than primary | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.34 |

| Primary completed | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.33 |

| Middle completed | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.32 |

| Secondary school complete | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.34 |

| Higher secondary and above | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.34 |

Note: The source was individual-level data from the Longitudinal Aging Study in India-Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia 2017 to 2019.

In the first step of our analysis, we provide descriptive statistics indicating the extent to which a sex gap in late-life cognition exists. In a second step, we rely on ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions to investigate which factors may explain the observed, unconditional sex gap in late-life cognition. Specifically, we regress score I and score II on an increasing set of explanatory variables. In our baseline specification, we include a female indicator, capturing differences in outcomes between female and male study participants, age, indicators for the language in which and the place where (hospital or home) the interview was conducted, and indicators for state and urban/rural area of residence. In our second specification, we add controls for early-life SES (namely, indicators for being born in a rural or urban area as well as for caste, religion, and parental education). In our third specification, we add knee height to proxy for early-life nutrition.33 Finally, in our last specification, we include indicators for the following levels of schooling: less than primary, primary, middle, secondary, and higher secondary and above, with no school as the reference category. The goals of this regression analysis are to determine to what extent early-life and contextual factors correlate with the observed sex gap in late-life cognition and to empirically establish their relative role in explaining sex differences in cognitive health. We use sample weights in all of our analyses to account for the sampling design of LASI-DAD as well as for differential nonresponse rates across segments of the population.

RESULTS

Sex Differences in Late-Life Cognition: Descriptive Statistics

We begin our empirical analysis by documenting unconditional differences across cognitive tests by sex. Table 2 presents mean and standard deviation (SD) of cognitive test scores included in score I and II, separately for women and men. The last column shows the observed sex difference in scores and tests whether it is statistically significant. With a few exceptions in the memory domain (word and story recall tasks), women appear to be at a disadvantage compared with men. Using the standardized score I, female study participants score, on average, 0.4 SDs less than their male counterparts. Sex disparities are more striking for cognitive tests that require literacy or numeracy. Referring to the standardized score II, women’s score is about 0.8 SDs less than men’s score, on average. As mentioned above, statistics based on a combined score comprising all cognitive tests administered in the LASI-DAD are similar to those based on score I. In fact, using a standardized overall cognition index, women score 0.44 SDs less than men, on average.

Table 2.

Mean Differences by Sex in Cognition Test Scores

| Variable | Women (N = 1,446) |

Men (N = 1,258) |

Women versus men Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Orientation to time (0–5) | 3.36 | 1.42 | 4.05 | 1.31 | −0.67*** |

| Orientation to place (0–5) | 3.86 | 1.17 | 4.48 | 0.85 | −0.66*** |

| Days of week backwards (0–6) | 3.25 | 2.69 | 4.50 | 2.34 | −1.20*** |

| Object naming (0–2) | 1.81 | 0.43 | 1.88 | 0.35 | −0.08*** |

| Repeat phrase (0–1) | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.92 | 0.27 | −0.08*** |

| Close eyes task (0–1) | 0.75 | 0.43 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.17*** |

| Paper folding task (0–3) | 2.52 | 0.78 | 2.70 | 0.61 | −0.15*** |

| Write/say a sentence (0–1) | 0.87 | 0.34 | 0.90 | 0.31 | −0.03** |

| Word recall: immediate, 3 attempts (0–30) | 11.62 | 5.34 | 12.06 | 4.96 | −0.32 |

| Word recall: delayed (0–10) | 3.21 | 2.50 | 3.26 | 2.27 | −0.01 |

| Word list recognition (0–20) | 15.94 | 3.73 | 16.52 | 3.18 | −0.67*** |

| Brave man story: immediate recall score (0–6) | 5.42 | 3.09 | 5.73 | 3.22 | −0.28* |

| Brave man story: delayed recall score (0–6) | 2.90 | 3.56 | 3.21 | 3.67 | −0.22 |

| Robbery story: immediate recall score (0–25) | 3.77 | 4.11 | 4.36 | 4.21 | −0.46** |

| Robbery story: delayed recall score (0–25) | 2.56 | 4.09 | 3.45 | 4.26 | −0.70*** |

| Logical memory recognition score (0–15) | 7.36 | 3.26 | 8.05 | 2.96 | −0.66*** |

| TICS 3-item score (0–3) | 1.87 | 0.91 | 2.26 | 0.83 | −0.41*** |

| Verbal fluency: animal naming (0–70) | 11.21 | 4.69 | 12.18 | 4.91 | −0.99*** |

| CSID 4-item score (0–4) | 3.42 | 0.84 | 3.59 | 0.71 | −0.16*** |

| Raven’s test score (0–17) | 7.24 | 3.21 | 8.23 | 3.50 | −0.88*** |

| Go-no-go total score (0–20) | 10.44 | 6.26 | 13.40 | 6.17 | −2.94*** |

| Draw overlapping pentagons (0–1) | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.48 | −0.18*** |

| Symbol cancellation score (0–57) | 5.59 | 7.59 | 9.90 | 9.86 | −3.97*** |

| Constructional praxis score (0–11) | 4.72 | 3.00 | 6.55 | 3.19 | −1.89*** |

| Constructional praxis score: recall (0–11) | 2.17 | 2.41 | 3.38 | 2.95 | −1.13*** |

| Summary score I: total | 116.84 | 43.91 | 136.48 | 44.49 | −18.58*** |

| Summary score I: standardized | −0.17 | 0.97 | 0.27 | 0.99 | −0.41*** |

| Serial 7s (0–5) | 1.78 | 1.73 | 3.00 | 1.71 | −1.16*** |

| Digit span forward (0–1) | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.48 | −0.14*** |

| Digit span backward (0–1) | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.50 | −0.21*** |

| Clock drawing score (0–3) | 0.69 | 0.94 | 1.37 | 1.12 | −0.66*** |

| Summary score II: total | 2.05 | 2.63 | 4.56 | 3.21 | −2.40*** |

| Summary score II: standardized | −0.36 | 0.84 | 0.44 | 1.03 | −0.77*** |

Note: Statistics are weighted.

The source was individual-level data from the Longitudinal Aging Study in India-Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia 2017 to 2019.

Abbreviations: CSID, Community Screening Interview for Dementia; TICS, Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status.

P < .10.

P < .05.

P < .01.

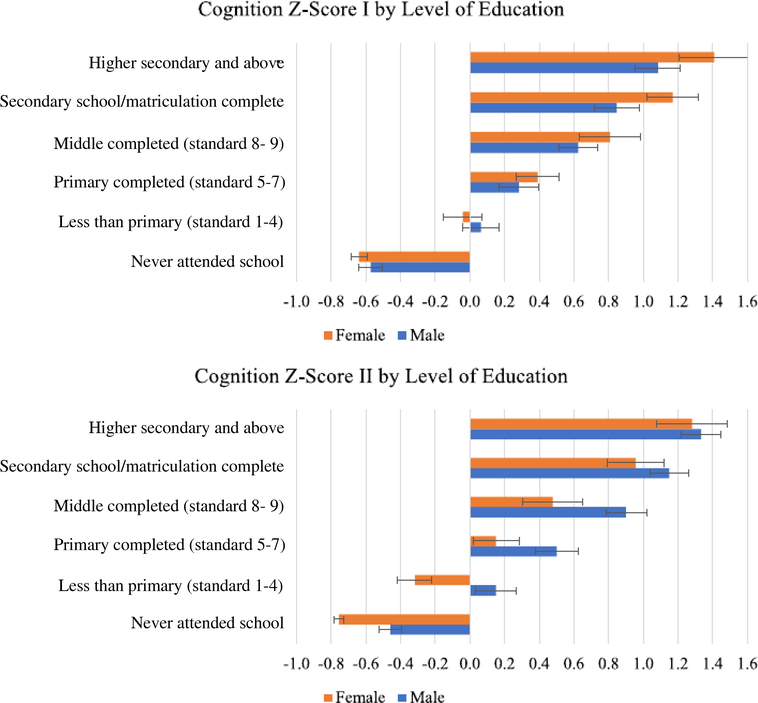

The unconditional differences just described may be confounded, among other things, by differences in educational achievement and/or differential mortality by sex. In Figure 1, we report the observed sex gap in late-life cognition by education. This breakdown reveals interesting patterns. A first noticeable fact is the steep increase of late-life cognitive functioning with educational achievement, which likely indicates a protective effect of education on cognition. The sharpest increase in score I is observed when moving from no school to at least some school. It amounts to more than 0.6 SDs and is the same for men and women. Completing primary, middle, and secondary school is associated with a larger increase in score I for women than for men, roughly 0.4 versus 0.3 SDs. Having higher secondary education is associated with a 0.25-SD increase in score I for both sexes. Within each education group, women tend to perform as well as men or better. In particular, at higher levels of education, women exhibit a positive gap of about 0.3 SDs compared with men, which is statistically significant. The protective effect of education on cognitive performance is equally evident when focusing on score II. In this case, the standardized composite score increases again by about 0.6 SDs when moving from no school to some school. From primary school onward, it increases, on average, by 0.3 and 0.4 SDs at each step on the education ladder for men and women, respectively. In contrast with what we have described for score I above, women tend to perform significantly worse than men in terms of score II within all education groups. The wider female gap of 0.5 SDs is observed among individuals with less than primary education. The female gap remains at around 0.4 SDs across other education groups. Only among individuals with higher secondary education, no significant differences in performance are detected between men and women.

Figure 1.

Cognition summary Z-scores by education. The source was individual-level data from the Longitudinal Aging Study in India–Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia 2017 to 2019.

We also examine differences by age bracket, 60 to 64, 65 to 69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, and 80 years or older, in Supplementary Figure S1, which shows an apparent worsening of cognitive performance with age for both men and women. As far as sex differences are concerned, women perform worse than men at any age. In terms of score I, the gap is slightly increasing with age. For score II, the female gap exhibits a decreasing tendency with age, but remains always above 0.65 SDs across age brackets. Based on these statistics by age, the female disadvantage in cognitive health observed in the whole sample does not seem to be driven by a widening sex gap at very old ages, which, as documented in developed countries, could reflect differential mortality by sex (e.g., given lower life expectancy for men, surviving men at very old ages would have unique attributes and systematically higher cognitive functioning than surviving women).25 We further investigate this issue below.

Determinants of Sex Differences in Late-Life Cognition: Regression Analysis

Moving beyond simple descriptive statistics, we estimate multivariate regression models by OLS to quantify the extent to which early-life and contextual factors explain the documented sex gap in late-life cognition. We present the results of this analysis in Table 3, where the top and bottom panels refer to regressions using score I and score II as dependent variable, respectively. The four columns in Table 3 report the estimated, conditional female gap for each of the four specifications described above (all other coefficients are available in the Supplementary Appendix S1).

Table 3.

OLS Estimates of Female Gap in Cognition

| Variable | Model 1: base | Model 2: add early-life SES variables | Model 3: add early life health | Model 4: add education |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-score: cognition I (no literacy and numeracy) | ||||

| Female | −0.45*** | −0.42*** | −0.33*** | −0.05 |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |

| [−0.52 to −0.38] | [−0.49 to −0.36] | [−0.41 to −0.25] | [−0.13 to 0.02] | |

| R2 | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.55 |

| Z-score: cognition II (literacy or numeracy) | ||||

| Female | −0.82*** | −0.79*** | −0.69*** | −0.37*** |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |

| [−0.89 to −0.75] | [−0.85 to −0.72] | [−0.77 to −0.60] | [−0.45 to −0.29]*** | |

| R2 | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.61 |

| Observations | 2,704 | 2,704 | 2,704 | 2,704 |

Note: Robust standard errors are in parentheses. The 95% confidence intervals are in brackets. Model 1 includes the following covariates other than a female indicator: binary indicators for age groups, state, rural, interview language, and interview location. Model 2 adds the following covariates: indicators for whether the individual was born in rural area, caste/tribe group, religion, whether mother attended school, and whether father attended school. Model 3 adds knee height to proxy for early-life nutrition. Model 4 adds indicators for different education levels. The full set of estimated coefficients is reported in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. The source is individual-level data from the Longitudinal Aging Study in India-Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia 2017 to 2019. Abbreviations: OLS, ordinary least squares; SES, socioeconomic status.

P < .10.

P < .05.

P < .01.

For score I, the estimated female gap in model 1, after adjusting for age, language, and location, is 0.45 SDs, hence similar to the unconditional difference reported in Table 2. Adding indicators for early-life SES in model 2 decreases the estimated gap only marginally. In contrast, including knee height, as a proxy for childhood nutrition, explains about 27% of the original female gap. When we add education in model 4, the residual gap is 0.05 SDs and no longer statistically significant. Thus, education explains 62% of the female gap. Overall, our richest specification accounts for almost 90% of the unconditional female gap in late-life cognition.

Although the empirical evidence for score II is qualitatively similar, there are notable quantitative differences. To start with, and in line with the descriptive statistics presented in the previous section, the original gap between women and men is substantially wider at about 0.8 SDs. As for score I, indicators of early-life SES do not seem to influence such gap. Childhood nutrition reduces the gap to 0.7 SDs, whereas education decreases it further to about 0.4 SDs. Overall, our richest model explains 55% of the original female gap in late-life cognition, with early-life nutrition and education contributing 16% and 39%, respectively.

Although the other estimated coefficients are omitted in the main text (but available in the Supplemental Appendix S1), it is worth alluding to a few salient patterns that emerge from them. The regressions for both score I and score II return the education gradients documented in Figure 1. There exist some differences across states and by language in terms of cognitive performance, but they are not always statistically significant. Living in a rural area and belonging to either a scheduled caste or a tribe are associated with lower cognition (about 0.2 SDs), even after controlling for education. On average, Muslim individuals exhibit lower scores than Hindu. Yet, this difference disappears when education is controlled for. Among early-life factors, both parental education (especially father’s) and knee height correlate strongly and significantly with late-life cognitive performance.

To further investigate how much of the estimated sex gap could be attributed to selectivity due to differential mortality, we amend our richest specification with interactions between the female indicator and age-group indicators. The results, presented in Table 4, confirm the absence of age dependency in the female cognition gap, as most of the estimated interaction terms are small in magnitude and statistically indistinguishable from zero. The only statistically significant coefficient is the one corresponding to the interaction between the female indicator and the 80 years and older age group in the regression using score II as dependent variable. Yet, this coefficient is positive, suggesting a narrowing of the female gap among those 80 years and older. Under the premise that women have longer life expectancy than men, this finding would be in contrast with selectivity due to differential mortality.

Table 4.

Exploring Age Dependency in Female Cognition Gap (Adding Interactions Between Female and Age Group Indicators to the Full Set of Covariates)

| Score I |

Score II |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 4 (all covariates) | Model 4 plus female × age interactions | Model 4 (all covariates) | Model 4 plus female × age interactions |

| Female | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.37*** | −0.40*** |

| (0.04) | (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.06) | |

| [−0.13 to 0.02] | [−0.18 to 0.04] | [−0.45 to −0.29] | [−0.51 to −0.28] | |

| Omitted age group: 60–64 y | ||||

| Age 65–69 y | −0.09*** | −0.14** | −0.02 | −0.01 |

| (0.04) | (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.06) | |

| [−0.17 to −0.02] | [−0.24 to −0.03] | [−0.10 to 0.05] | [−0.13 to 0.10] | |

| Age 70–74 y | −0.25*** | −0.25*** | −0.11*** | −0.13** |

| (0.04) | (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.06) | |

| [−0.33 to −0.16] | [−0.37 to −0.13] | [−0.19 to −0.03] | [−0.25 to −0.01] | |

| Age 75–79 y | −0.43*** | − 0.40*** | −0.20*** | −0.25*** |

| (0.05) | (0.07) | (0.04) | (0.08) | |

| [−0.53 to −0.34] | [−0.55 to −0.26] | [−0.28 to −0.11] | [−0.40 to −0.10] | |

| Aged ≥80 y | −0.66*** | −0.65*** | −0.25*** | −0.35*** |

| (0.05) | (0.08) | (0.04) | (0.08) | |

| [−0.77 to −0.56] | [−0.80 to −0.49] | [−0.34 to −0.16] | [−0.49 to −0.20] | |

| Female × age 65–69 y | 0.08 | −0.03 | ||

| (0.07) | (0.07) | |||

| [−0.06 to 0.23] | [−0.17 to 0.12] | |||

| Female × age 70–74 y | −0.01 | 0.05 | ||

| (0.09) | (0.08) | |||

| [−0.18 to 0.17] | [−0.11 to 0.20] | |||

| Female × age 75–79 y | −0.05 | 0.10 | ||

| (0.10) | (0.09) | |||

| [−0.24 to 0.14] | [−0.08 to 0.28] | |||

| Female × age ≥80 y | −0.03 | 0.18** | ||

| (0.11) | (0.09) | |||

| [−0.24 to 0.18] | [0.00 to 0.35] | |||

| Constant | −0.47 | −0.46 | −0.49* | −0.47* |

| (0.29) | (0.29) | (0.28) | (0.28) | |

| [−1.03 to 0.10] | [−1.03 to 0.11] | [−1.04 to 0.07] | [−1.02 to 0.09] | |

| Observations | 2,704 | 2,704 | 2,704 | 2,704 |

| R2 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

Note: Robust standard errors are in parentheses. The 95% confidence intervals are in brackets. Other covariates are binary indicators for age groups, state, rural, interview language, and interview location; indicators for whether the individual was born in rural area, caste/tribe group, religion, whether mother attended school, and whether father attended school; knee height to proxy for early-life nutrition; and indicators for different education levels. The source was individual-level data from the Longitudinal Aging Study in India-Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia 2017 to 2019.

P < .10.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Last, we assess the robustness of our results to using nonimputed cognition test scores and to estimating our two most parsimonious models without excluding individuals with missing values for early-life SES and knee height (the two covariates with the largest number of missings). The results of these exercises, reported in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4, respectively, show that our main conclusions are unaffected both qualitatively and quantitatively.

DISCUSSION

We focus on sex differences in late-life cognition in the context of India, exploiting unprecedented rich data on cognitive health for a large, representative sample of the Indian population aged 60 years and older. We document an apparent female gap across cognitive domains among older Indians, with substantial heterogeneity across age and education groups. We shed light on the extent to which contextual and early-life factors explain the observed women’s disadvantage in late-life cognition and quantify their relative contribution.

Overall, older Indian female adults are at a disadvantage relative to their male counterparts in terms of cognitive performance. This phenomenon is apparent whether we focus on cognitive tests that do not explicitly require literacy or numeracy or on those tests that do require such skills. The gap in basic cognitive functions is wider within the oldest cohorts (aged ≥75 years) than within the younger ones (aged ≤65 years). This may underlie a potential, protective role of education, as women from younger cohorts have achieved relatively higher levels of schooling. At the same time, it could result from selectivity due to differential mortality by sex. Yet, this pattern is reversed when focusing on cognitive tests requiring literacy or numeracy. The breakdown by education offers two main conclusions. First, by and large women exhibit an advantage in terms of basic cognitive functions when they are compared with similarly educated men. This is consistent with the evidence from developed countries, where the education gap by sex is negligible and older women perform as well as older men or better in most cognitive domains. Second, the female gap in cognitive tests requiring literacy or numeracy conditional on education may suggest inequality of opportunities for Indian women, who, relative to men, may lack stimuli and exposure to verbal and numerical tasks/problems that are typically associated with social and labor market activities. The fact that female participants with higher secondary education perform as well as their male counterparts in more numerical oriented cognitive tests likely stems from a selection mechanism by which only women with above average cognitive abilities achieve beyond primary and middle education.

Our data allow us to investigate to what extent early-life and contextual factors help explain the observed female gap in late-life cognition. This represents a major contribution of this study to the existing literature. We find that sex differences in education are the main determinant of the observed female gap in late-life cognition. Specifically, education explains more than 60% of the female gap in cognitive tests that do not require literacy or numeracy, and about 40% of the female gap in cognitive tests that do call for such skills. The second largest contributor to the existing disparities in late-life cognitive performance is childhood nutrition, as proxied by knee height, which explains about 30% and 15% of the gap in scores I and II, respectively. Other contextual factors and early-life socioeconomic indicators, such as caste, religion, and parental education, do correlate with cognitive test scores, but explain relatively little of the existing disparities in cognitive performance by sex. We include interaction terms between female and age-group indicators in our models and find no evidence that the female gap in late-life cognition is age dependent.

Overall, our model accounts for 90% of the observed female gap in basic cognitive functions, suggesting that such gap can be largely eliminated by equalizing health investments and educational achievement across sexes. In contrast, we are able to explain only about 55% of the female gap in cognitive tests that require literacy or numeracy. This may indicate that inequality of social and labor market opportunities created by sex biases and discriminating practices may have important adverse consequences for late-life cognitive health. At the same time, the observed difference between the results using score I and score II may constitute evidence of differential item functioning (DIF) by sex induced by differences in literacy between men and women. Cognitive test items in the pilot LASI exhibit bias by literacy.49 Should this finding extend to the items in the LASI-DAD, it could partly explain the larger female gap in cognitive performance when the composite score is based on tests requiring literacy or numeracy. We leave the investigation of these potential mechanisms—sex discrimination and DIF—for future research.

Consistently lower scores on cognitive tests spanning multiple domains signal greater risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. The results of this study can inform public health policy priorities in terms of targeting demographic subpopulations, like women with low levels of education, who have a plausibly higher risk of cognitive impairment and/or dementia among Indian older adults. Our findings also provide robust evidence for modifiable early-life factors associated with later-life risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in the context of a developing country, such as India, characterized by sustained and fast economic growth, but sociocultural norms that greatly limit access to education and labor market opportunities to women. Given the longer longevity of women relative to men, reducing sex inequality in late-life cognition may have important positive consequences for the future health of the rapidly aging Indian population.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1: All Regression Coefficients, Score I.

Supplementary Table S2: All Regression Coefficients, Score II.

Supplementary Table S3: OLS Estimates of Female Gap in Cognition Using Nonimputed Scores.

Supplementary Table S4: Estimations of Models 1 and 2 Without Excluding Individuals with Missing Covariates.

Supplementary Figure S1: Cognition summary Z-scores by age group.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial Disclosure: This project is funded by the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (R01AG051125 and RF1AG055273)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Sponsor’s Role: The National Institute on Aging had no role in preparing the data or the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: We obtained ethics approval from the University of Southern California.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaji KS, Jotheeswaran A, Girish N, et al. The Dementia India Report: Prevalence, Impact, Costs and Services for Dementia: Executive Summary. New Delhi, India: Alzheimer’s and Related Disorders Society of India; 2010:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prince MJ, Prina P, Guerchet M. World Alzheimer Report 2013 - Journey of Caring: An Analysis of Long-Term Care for Dementia. London, UK: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2013. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2013.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang L, Clifford A, Wei L, et al. Prevalence and determinants of undetected dementia in the community: a systematic literature review and a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e011146 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez JJL, Ferri CP, Acosta D, et al. Prevalence of dementia in Latin America, India, and China: a population-based cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2008;372(9637):464–474. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganguli M, Ratcliff G, Chandra V, et al. A hindi version of the MMSE: the development of a cognitive screening instrument for a largely illiterate rural elderly population in India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1995;10(5):367–377. 10.1002/gps.930100505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prince M, Acosta D, Chiu H, Scazufca M, Varghese M. Dementia diagnosis in developing countries: a cross-cultural validation study. Lancet. 2003;361 (9361):909–917. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12772-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J, Shih R, Feeney K, Langa KM. Gender disparity in late-life cognitive functioning in India: findings from the Longitudinal Aging Study in India. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(4):603–611. 10.1093/geronb/gbu017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishna M, Beulah E, Jones S, et al. Cognitive function and disability in late life: an ecological validation of the 10/66 battery of cognitive tests among community-dwelling older adults in South India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(8):879–891. 10.1002/gps.4404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lei X, Hu Y, McArdle JJ, Smith JP, Zhao Y. Sex differences in cognition among older adults in China. J Hum Resour. 2012;47(4):951–971. 10.3368/jhr.47.4.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strauss J, Witoelar F, Meng Q, et al. Cognition and SES Relationships Among the Mid-Aged and Elderly: A Comparison of China and Indonesia. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maurer J Education and male-female differences in later-life cognition: international evidence from Latin America and the Caribbean. Demography. 2011;48(3):915–930. 10.1007/s13524-011-0048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yount KM. Gender, resources across the life course, and cognitive functioning in Egypt. Demography. 2008;45(4):907–926. 10.1353/dem.0.0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langa KM, Larson EB, Karlawish JH, et al. Trends in the prevalence and mortality of cognitive impairment in the United States: is there evidence of a compression of cognitive morbidity? Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(2):134–144. 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langa KM, Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, et al. Cognitive health among older adults in the United States and in England. BMC Geriatr. 2009;9(1):23 10.1186/1471-2318-9-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oksuzyan A, Crimmins E, Saito Y, O’Rand A, Vaupel JW, Christensen K. Cross-national comparison of sex differences in health and mortality in Denmark, Japan and the US. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(7):471–480. 10.1007/s10654-010-9460-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzpatrick AL, Kuller LH, Ives DG, et al. Incidence and prevalence of dementia in the cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2): 195–204. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(6): 427–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocca WA, Petersen RC, Knopman DS, et al. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and cognitive impairment in the United States. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(1):80–93. 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersen K, Launer LJ, Dewey ME, et al. Gender differences in the incidence of AD and vascular dementia. Neurology. 1999;53(9):1992–1997. 10.1212/WNL.53.9.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fratiglioni L, Viitanen M, von Strauss E, Tontodonati V, Herlitz A, Winblad B. Very old women at highest risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1997;48(1):132–138. 10.1212/WNL.48.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin KA, Choudhury KR, Rathakrishnan BG, Marks DM, Petrella JR, Doraiswamy PM. Marked gender differences in progression of mild cognitive impairment over 8 years. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2015;1(2):103–110. 10.1016/j.trci.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perls TT, Morris JN, Ooi WL, Lipsitz LA. The relationship between age, gender and cognitive performance in the very old: the effect of selective survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(11):1193–1201. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb07302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suthers K, Kim JK, Crimmins E. Life expectancy with cognitive impairment in the older population of the United States. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(3):S179–S186. 10.1093/geronb/58.3.S179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mielke MM, Vemuri P, Rocca WA. Clinical epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: assessing sex and gender differences. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:37–48. 10.2147/CLEP.S37929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayeda ER. Invited commentary: examining sex/gender differences in risk of Alzheimer disease and related dementias—challenges and future directions. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(7):1224–1227. 10.1093/aje/kwz047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S, Kawachi I, Berkman LF, Grodstein F. Education, other socioeconomic indicators, and cognitive function. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(8):712–720. 10.1093/aje/kwg042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banks J, Mazzonna F. The effect of education on old age cognitive abilities: evidence from a regression discontinuity design. Econ J (London). 2012;122 (560):418–448. 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2012.02499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glymour MM, Kawachi I, Jencks CS, Berkman LF. Does childhood schooling affect old age memory or mental status? using state schooling laws as natural experiments. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(6):532–537. 10.1136/jech.2006.059469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jefferson AL, Gibbons LE, Rentz DM, et al. A life course model of cognitive activities, socioeconomic status, education, reading ability, and cognition. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(8):1403–1411. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meng X, D’Arcy C. Education and dementia in the context of the cognitive reserve hypothesis: a systematic review with meta-analyses and qualitative analyses. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38268 10.1371/journal.pone.0038268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang W, Zhou Y. Effects of education on cognition at older ages: evidence from China’s great famine. Soc Sci Med. 2013;98:54–62. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Case A, Paxson C. Height, health, and cognitive function at older ages. Am Econ Rev. 2008;98(2):463–467. 10.1257/aer.98.2.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang TL, Carlson MC, Fitzpatrick AL, Kuller LH, Fried LP, Zandi PP. Knee height and arm span: a reflection of early life environment and risk of dementia. Neurology. 2008;70(19, pt 2):1818–1826. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000311444.20490.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maurer J Height, education and later-life cognition in Latin America and the Caribbean. Econ Hum Biol. 2010;8(2):168–176. 10.1016/j.ehb.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guven C, Lee W-S. Height, aging and cognitive abilities across Europe. Econ Hum Biol. 2015;16:16–29. 10.1016/j.ehb.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosca I, Wright RE. Height and cognition at older ages: Irish evidence. Econ Lett. 2016;149:98–101. 10.1016/j.econlet.2016.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Z, Gu D, Hayward MD. Childhood nutritional deprivation and cognitive impairment among older Chinese people. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(5): 941–949. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Z, Liu J, Li L, Xu H. The long arm of childhood in China: early-life conditions and cognitive function among middle-aged and older adults. J Aging Health. 2018;30(8):1319–1344. 10.1177/0898264317715975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krishna M, Kumar GM, Veena SR, et al. Birth size, risk factors across life and cognition in late life: protocol of prospective longitudinal follow-up of the MYNAH (MYsore studies of Natal effects on Ageing and Health) cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012552 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grove BJ, Lim SJ, Gale CR, Shenkin SD. Birth weight and cognitive ability in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Int. 2017;61: 146–158. 10.1016/j.intell.2017.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krishna M, Jones S, Maden M, et al. Size at birth and cognitive ability in late life: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(8):1139–1169. 10.1002/gps.5138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prince M, Acosta D, Dangour AD, et al. Leg length, skull circumference, and the prevalence of dementia in low and middle income countries: a 10/66 population-based cross sectional survey. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(2):202–213. 10.1017/S1041610210001274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.School Education | Government of India, Ministry of Human Resource Development. https://mhrd.gov.in/rte. Published 2019. Accessed December 1, 2019.

- 44.Lee J, Banerjee J, Khobragade PY, Angrisani M, Dey AB. LASI-DAD study: a protocol for a prospective cohort study of late-life cognition and dementia in India. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e030300 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gross AL, Khobragade PY, Meijer E, Saxton JA. Measurement and Structure of Cognition in the Longitudinal Aging Study in India–Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:S11–S19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cline MG, Meredith KE, Boyer JT, Burrows B. Decline of height with age in adults in a general population sample: estimating maximum height and distinguishing birth cohort effects from actual loss of stature with aging. Hum Biol. 1989;61(3):415–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sorkin JD, Muller DC, Andres R. Longitudinal change in height of men and women: implications for interpretation of the body mass index: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(9):969–977. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang W, Lei X, Ridder G, Strauss J, Zhao Y. Health, height, height shrinkage, and SES at older ages: evidence from China. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2013;5(2):86–121. 10.1257/app.5.2.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goel A, Gross A. Differential item functioning in the cognitive screener used in the Longitudinal Aging Study in India. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31:1–11. 10.1017/S1041610218001746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1: All Regression Coefficients, Score I.

Supplementary Table S2: All Regression Coefficients, Score II.

Supplementary Table S3: OLS Estimates of Female Gap in Cognition Using Nonimputed Scores.

Supplementary Table S4: Estimations of Models 1 and 2 Without Excluding Individuals with Missing Covariates.

Supplementary Figure S1: Cognition summary Z-scores by age group.