Abstract

SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of the COVID-19 pandemic, is an RNA virus that has inherent high rate of mutation. Due to the mutations, the virus evolves at a rapid pace that helps them to survive better inside the host. One of the hotspots of pharmacological interventions is to inhibit binding of virus with the host cells, which is mediated by Spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 receptors present on the human cells. This study was conducted with an aim to identify and characterise the mutation (s) present in the Spike glycoprotein of the SARS-CoV-2. Towards this, an in silico methodology was used, and the mutations on Spike glycoprotein were identified by comparing the Spike glycoprotein of first reported sequence from Wuhan wet seafood market virus with the available sequences of SARS-CoV-2 from Indian isolates. Our analysis revealed the presence of twenty-five mutations in Spike glycoprotein among Indian SARS-CoV-2 isolates. These mutations spread all over the protein and can be clustered at least into four distinct positions. Further, mutations at eleven positions exhibited alterations in the secondary structure of the polypeptide chain. We also investigated the influence of these mutations on overall protein dynamics and have shown that they affect the dynamic stability of the Spike glycoprotein.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Spike glycoprotein, Mutation, Indian geographical area

Highlights

-

•

Spike glycoprotein is frequently mutated as it spreads to new locations.

-

•

SARS-CoV-2 harbours 25 mutations in its Spike glycoprotein among Indian Isolates.

-

•

Most of the mutations on Spike glycoprotein are localised in four clusters.

-

•

Mutations at eleven positions alter secondary structure and dynamicity of Spike protein.

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has recently been reported as a human pathogen in the city of Wuhan in China's Hubei province, causing COVID-19 (Chan et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020) with normal to severe respiratory problems among other symptoms. According to the publicly available datasets on various online platforms, as of 25th May 2020, there are more than 5.4 million global confirmed cases of COVID-19 and at least 0.34 million deaths. SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped virus with a positive-sense RNA genome of approximately 29.8 kb in length, that encodes structural (spike, membrane, envelope protein, and nucleocapsid) and 16 non-structural proteins (nsp1 to nsp16) (Lu et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2, being an RNA virus, is potentially endowed with a high mutation rate (Pachetti et al., 2020). These mutations contribute to minor variations in the viral genome and drive them to confer resistance to host immune system as well as to develop drug resistance (Fung and Liu, 2019; Tay et al., 2020).

SARS-CoV-2 utilises a densely glycosylated spike (S) protein to access entry into host cells. The viral Spike glycoprotein is localised in the outermost layer of their envelope and is indispensable for attaching with the host receptor protein, Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2). Once attached to the host cell receptor, the Spike glycoprotein goes through an extensive structural rearrangement that enables the fusion of the viral and host cell membranes (Bosch et al., 2003; Li, 2016). The Spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 is 1273 amino acids long and is comprised of a distinct N-terminal domain, receptor-binding domain, subdomain 1/2, transmembrane domain, C-terminal domain with heptad repeats 1/2 and a cytoplasmic tail (Wrapp et al., 2020). Further, each Spike monomer consists of an N-terminal S1 domain and a membrane proximal S2 domain that mediate receptor binding and membrane fusion, respectively (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Walls et al., 2020). The N-terminal S1 region of Spike glycoprotein interacts with ACE2 receptor to attach with the host cell. Because of the indispensable function of the S protein, it is one of the most attractive viral target molecules for various interventions.

The SARS-CoV-2 spread worldwide within a few months (Sohrabi et al., 2020) and its rapid global reach provided the virus an ample opportunity to mutate and for natural selection to act (Duffy, 2018). Most likely, due to these mutations in SARS-CoV-2 the new and more resistant strains are constantly getting generated, which can successfully evade host immune system and nullify pharmacological molecules designed against them (Chand et al., 2020; Korber et al., 2020a). Therefore, in this study we decided to investigate the variations, if any, in the Spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 isolated from different geographical regions of India and compare them with the first reported isolate from ‘Wuhan wet seafood market virus’. Here, we identified twenty-five mutations in Spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 isolated from India and their probable implications on protein dynamicity have also been discussed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sequence retrieval

As of 6th June 2020, the NCBI-Virus-database has 153 Spike glycoprotein sequences of SARS-CoV-2 deposited from India. All these (153) sequences were downloaded and their protein database accession numbers are shown in supplementary table 1. For comparison, we retrieved the Spike glycoprotein sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 that was first reported genome sequence deposited in the NCBI-Virus-database from the ‘Wuhan wet seafood market area’ (formerly called ‘Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus’) during the initial days of COVID-19 spread (Wu et al., 2020) having the protein database accession number ‘YP_009724390’.

2.2. Sequence alignments

All the 153 Spike glycoprotein sequences (Indian isolates) and the reference (Wuhan isolate) were downloaded from the NCBI-Virus-database. We used these sequences for multiple sequence alignment using the CLUSTAL Omega web server provided by EMBL's European Bioinformatics Institute, UK (Madeira et al., 2019). This platform employs seeded guide trees and HMM profile-profile methodologies to form alignments among three or more input sequence data-sets. The output alignment files were analysed and the mismatched amino acid were carefully recorded.

2.3. Secondary structure predictions

To obtain a basic idea about the probable secondary structure, we input the mutant portion of Indian isolates' sequences and that of the Wuhan isolate (reference) into CFSSP (Chou and Fasman secondary structure prediction) (Ashok Kumar, 2013). This web server predicts the most plausible secondary structure, for instance, α helix, β sheet, and turns from the provided input amino acid sequence. CFSSP utilises the Chou-Fasman algorithm that uses solved X-ray crystallography structures of proteins to predict the relative frequencies of each input amino acid in the secondary structures of proteins.

2.4. Protein dynamics study

To evaluate the effect of mutations on protein structure, we have used mCSM web server (Pires et al., 2014). We uploaded the recently reported structure of SARS-CoV-2 from RCSB dataset [PDB ID: 6VYB (Walls et al., 2020)] to mCSM server, which in turn calculates and provides the impact of a mutation on the atomic-distance patterns surrounding the target residue (amino acid). mCSM tool relies on graph-based signatures to measure the protein fluctuations (Pires et al., 2014). mCSM works on the principle that the impact of a mutation can be correlated with the atomic distance patterns surrounding an amino acid residue. mCSM encodes distance patterns between atoms (up to 10 A°) and are used to represent the protein residue environment and also to train predictive models (Pires et al., 2014).

For examining the effect of mutations on the structural conformation and intramolecular interactions in the target protein, we used DynaMut web server (Rodrigues et al., 2018). The crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Spike glycoprotein ectodomain (open configuration); PDB ID: 6VYB (Walls et al., 2020) was uploaded onto DynaMut web server. Doing so, we have analysed the effects of the mutations in multiple protein structure stability factors including the vibrational entropy, atomic fluctuations and deformation energies. The DynaMut program models conformational alterations and measures the outcome of mutations on protein dynamics and stability. The calculations were executed over the first ten non-trivial modes of the protein molecule. Further, the DynaMut integrates graph-based signatures alongside normal mode dynamics to create a consensus prediction of the effect of any mutation on protein dynamicity (Rodrigues et al., 2018). DynaMut additionally provides estimates to gauge changes occurred on protein folding free energy by combining the information determined by Bio3D, ENCoM and DUET to produce an advanced and increasingly strong indicator (Rodrigues et al., 2018). The DynaMut also incorporates a lot of correlative data with respect to the environmental characteristics of the wild-type residues such as relative solvent accessibility, residue depth and secondary structure to calculate the impact of mutation on protein dynamicity (Rodrigues et al., 2018).

3. Results

3.1. Multiple sequence alignment to identify Spike glycoprotein mutations from Indian isolates

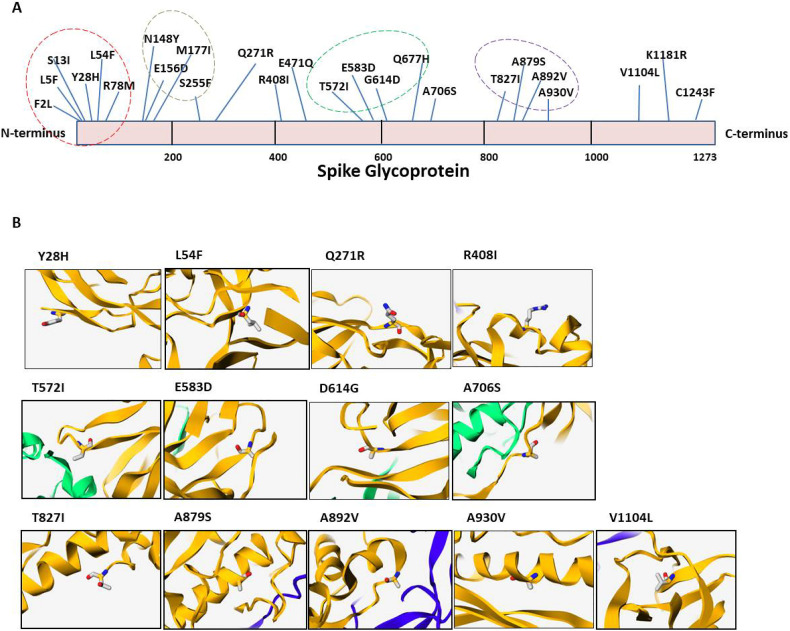

Overall, 153 Spike glycoprotein sequences, reported till 6th May 2020 from various parts of India, were downloaded from the NCBI-Virus-database and analysed by sequence alignment to identify any mutations. The sequence of Spike glycoprotein isolated from Wuhan (YP_009724390) has been used as a reference in this report. We observed a total of 25 mutations in Spike glycoprotein as shown in Fig. 1A. More importantly, our analysis shows that approximately 88% (134 out of 153) of the Indian samples harbour D614G mutation marking it as a dominant strain of SARS-CoV-2 in India. Among these, triple mutations occurred in the two Indian isolate QJR84429 (D614G, A706S and C1243F) and QJX44562 (L54F, E471Q and D614G). Furthermore, our data shows that there are 46 mutants that have double mutations (D614G with another mutation) and the rest have single mutation only. The tables showing the list of mutations identified in this study are listed in supplementary tables 2a and 2b. Moreover, these mutations are spread all over the Spike glycoprotein; however, four distinct clusters were observed between residues 1–100, 148–255, 570–680 and 820–930 as highlighted in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

A) The sequences of Spike glycoprotein obtained from India were aligned with the sequence from Wuhan (wet seafood market) SARS-CoV-2. The mutations were identified by amino acid sequence alignment by CLUSTAL Omega. The mutant residues are highlighted in the scheme of Spike glycoprotein. The Spike glycoprotein sequence of Wuhan SARS-CoV-2 was used as reference. The dotted circle represents mutation clusters. B) The location of mutant amino acids in the secondary structure of the Spike glycoprotein. The position of each amino acid mutation is highlighted as sticks in their respective panels.

Next, we analysed the location of these mutations in the secondary structure of the Spike glycoprotein by utilising the mCSM tool (Pires et al., 2014). The analysis shows that thirteen mutations are present on those areas of Spike glycoprotein whose structure has been solved recently by crystallography. Out of these, four mutations are in the β sheet (namely 28, 271, 614 and 1104), three are in α helix (408, 879 and 930) and rest are in loop areas (572, 583, 614, 706, 827 and 892) as shown in Fig. 1B.

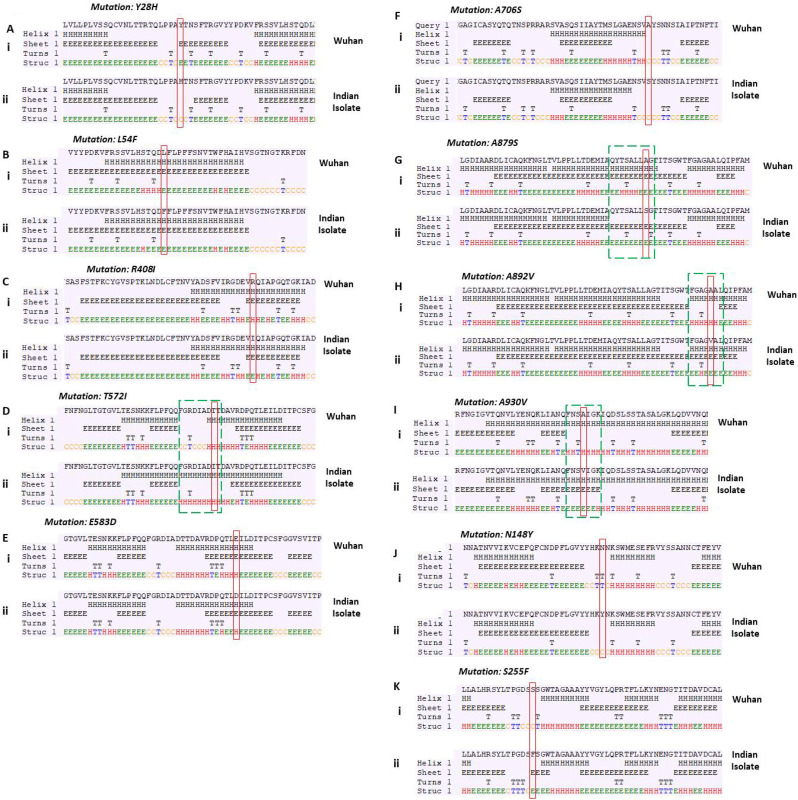

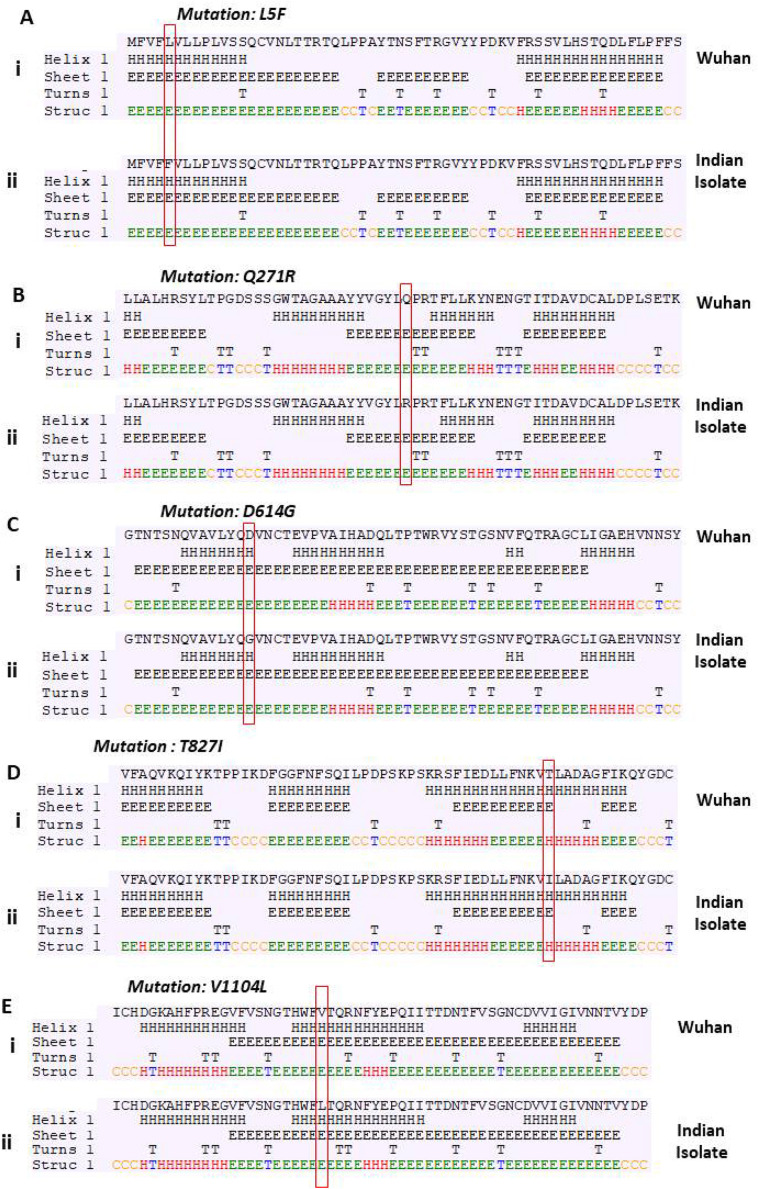

3.2. The mutations in Spike glycoprotein leads to alteration in secondary structure

Next, we investigated the effect of these mutations on the structure of Spike glycoprotein. On analysing the secondary structures using secondary structure prediction tool, we observed that eleven mutations are leading to alteration in secondary structure as shown in Fig. 2 (compare panel i and ii). However, five mutations failed to show any effect on the secondary structure (Supplementary Fig. 1). Out of the eleven mutations that alter the secondary structure, four of them have a drastic effect as highlighted with box (panel D, G, H and I). Our analysis revealed that the T572I mutation is causing the shifting of coiled region to helix (Fig. 2D); however, A879S, A892V and A930V mutations lead to replacement of helix with beta-sheet (Fig. 2G, H and I; compare panel i and ii). Further, our results are in consistence with earlier reports that have shown alanine as a good helix-forming amino acid residue as compared to valine, which is a bad helix-forming residue at certain positions in α-helix of a native protein (Gregoret and Sauer, 1998).

Fig. 2.

Prediction of changes in the secondary structure of Spike glycoprotein due to mutations. Fig. A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J and K demonstrate mutations observed in Indian isolates. Panel (i) represents sequence of Wuhan isolate and panel (ii) represents sequence of Indian isolates. We observed a drastic change in the secondary structure between Wuhan and Indian isolates at four mutation sites as highlighted in the green box (Panel D, G, H and I). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Prediction of changes in the secondary structure of Spike glycoprotein due to mutations. Fig. A, B, C, D and E demonstrate mutations observed in Indian isolates. Panel (i) represents sequence of Wuhan isolate; panel (ii) represents that of the Indian isolates.

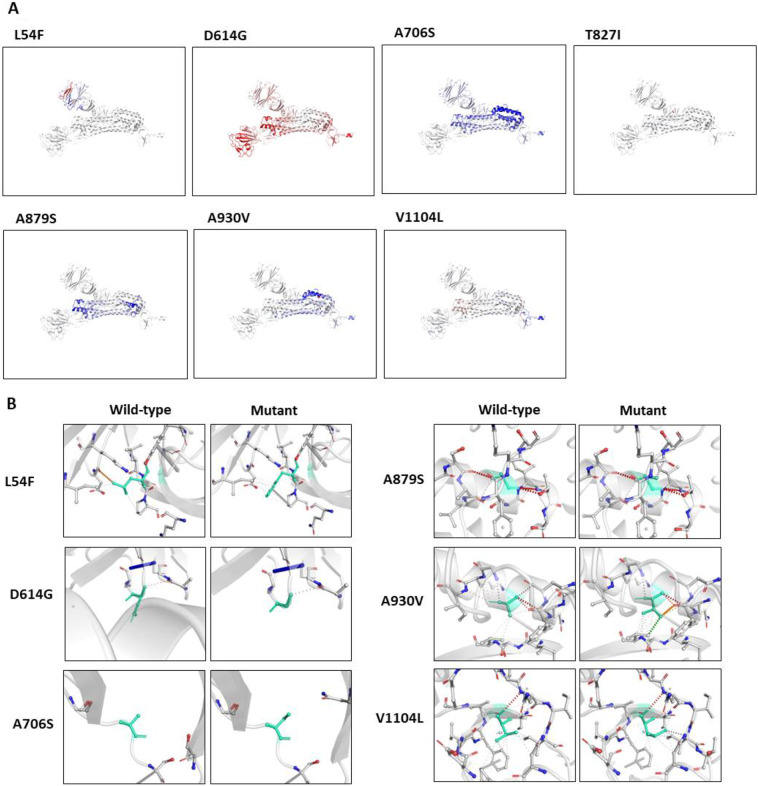

3.3. The mutations influence the dynamic stability of Spike glycoprotein

To assess the effect of the mutations on the structural dynamics of Spike glycoprotein, we measured the differences of free energy (ΔΔG) between wild-type and mutant. The ΔΔG, as a consequence of mutation, correlates with the structural changes in three-dimensional structure of protein, and, thus, measures the effect of mutation on protein stability (Eriksson et al., 1992). The value of ΔΔG below zero signifies destabilisation and above zero represents stabilisation in protein structure. Here, our analysis showed positive ΔΔG for eight mutations and negative for five mutations as shown in Table 1 . We have observed high positive ΔΔG for V1104L, L54F, A930V and D614G, indicating stabilising mutation (more than 0.4 kcal.mol−1); on the other hand, A879S yielded a high negative ΔΔG (approx. -0.4 kcal.mol−1) indicating destabilisation.

Table 1.

The analysis of ΔΔG and ΔΔSVib ENCoM between wild-type and mutant SARS-CoV-2 Spike glycoprotein. DynaMut webserver was used to calculate the above two parameters.

| S. No | Mutation | ΔΔG (kcal/mol) |

ΔΔSVib ENCoM kcal.mol−1.K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | V1104L | 0.687 | −0.102 |

| 2 | L54F | 0.558 | −0.26 |

| 3 | A930V | 0.486 | −0.408 |

| 4 | D614G | 0.406 | 0.047 |

| 5 | Q271R | 0.379 | 0.092 |

| 6 | T572I | 0.296 | −0.025 |

| 7 | A706S | 0.167 | −0.644 |

| 8 | T827I | 0.044 | 4.943 |

| 9 | R408I | −0.014 | 0.16 |

| 10 | A892V | −0.05 | 0.084 |

| 11 | E583D | −0.143 | 0.293 |

| 12 | Y28H | −0.217 | 0.035 |

| 13 | A879S | −0.384 | −0.389 |

Further, to evaluate the consequences of these mutations on the structural dynamics of the Spike glycoprotein, we performed protein modelling to analyse the change in vibrational entropy energy between wild-type and mutant protein (ΔΔSVibENCoM). Vibration entropy is the major contributor of the configurational-entropy of the proteins (Goethe et al., 2015). By definition, the negative ΔΔSVibENCoM signifies the rigidification and a positive value represents gain in flexibility of the protein structure. Our analysis shows a very high ΔΔSVibENCoM for T827I mutation (4.94 kcal.mol−1.K−1), which indicates gain in flexibility of the protein structure (Table 1). A930V, A879S and A706S cause considerable negative ΔΔSVibENCoM (in the range of −0.4 kcal.mol−1.K−1), which indicates rigidification in the protein structure.

Subsequently, we also analysed the impact of the mutations on the overall protein structural flexibility. We selected those mutations that exhibited larger alteration in ΔΔG as well as in ΔΔSVibENCoM (shown in Table 1). Our data revealed that L54F, T827I and V1104L mutations induce localised alteration in protein structure (Fig. 3A); however, D614G, A706S, A879S and A930V exhibit alteration in a broader region of the protein structure (Fig. 3A). Altogether, our ΔΔG and ΔΔSVibENCoM data revealed that mutations at 54, 614, 706, 879, 930 and 1104 have a greater impact on protein stability and structural dynamics. Therefore, we sought to analyse the impact of these mutations on the close range interactions made by mutant amino acids in the Spike glycoprotein. Our data show that the substitutions of the wild type amino acids by mutant ones are notably affecting the intramolecular bonds in the pockets where these amino acids reside (Fig. 3B). Specifically, considering L54F, D614G, A930V and V1104L mutations, the difference in intramolecular interactions between the wild type and mutants are distinct (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Prediction of mutation impact on structural integrity of Spike glycoprotein, A) Analysis of protein flexibility due to mutations in Spike glycoprotein. The blue color signifies rigidification of the structure and red represents gain in flexibility. B) Interatomic interactions in Spike glycoprotein- The molecular structure of wild-type and mutant amino acid are highlighted in light-green color. The surrounding residues that are making close contacts with the wild type and mutant residues are also highlighted. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

Within a span of six months, the COVID-19 pandemic spread rapidly to more than 200 countries and territories in different continents. We sought to understand whether the migration of SARS-CoV-2 into different geographical areas is causing generation of distinct SARS-CoV-2 strains, because of variation in temperature, climate and the host human populations. We performed an in silico analysis on publicly available data of RNA sequences of SARS-CoV-2 isolates from India and compared them with the first reported virus from Wuhan province, China. Here, we have reported the occurrence of twenty-five mutations in the Spike glycoprotein isolated from India (Fig. 1A and Supplementary table 2). Large scale analyses have shown that SARS-CoV-2 in most of the countries have evolved to various mutated strains and Spike glycoprotein is one of the mutational hot spots (Pachetti et al., 2020; Phelan et al., 2020). More recently, a study with 3067 genomic sequence of SARS-CoV-2 identified approximately 450 non-synonymous mutations (Laamarti et al., 2020). Consistent with these reports, our study also shows various mutations in Spike glycoprotein. In addition, we have also observed four distinct clusters where the prevalence of mutations is very high compared to other regions of the protein structure. Interestingly, at the N-terminal end (residues 1–200) there are nine mutations and this region is a part of NTD of Spike glycoprotein that is known to be N-linked glycosylated (Fung and Liu, 2018). The other two mutation clusters in S1 and S2 domains of Spike glycoprotein. Furthermore, we found some mutations that reside at very important locations in this protein. One of the mutations identified in this study is Q677H, which is just four residues upstream of S1/S2 conserved site and it could potentially affect the processing at S1/S2 site. The Spike glycoproteins are present on viral envelope and aid in viral entry to ACE2 expressing host cells. During this process, the S1 domain interacts with host cell receptor whereas the S2 domain is involved in fusion of the viral membrane with the host cell lipid membrane (Lan et al., 2020). The initiation of lipid membrane fusion is primarily subjected to the Spike glycoprotein cleavage by host cell proteases at the S1/S2 (residue 681/682) (Markus Hoffmann, 2020).

The structural studies on hACE2 and Spike glycoprotein interactions revealed that there are strong polar contacts between the SARS-CoV-2 Spike residue A475 and E484 (present on a long loop region) with hACE2 residues (Wang et al., 2020). In this study, we have identified another mutation E471Q, which is also present in the same loop region and we hypothesize that this mutation might affect the interactions mediated by A475 residue with hACE2. Among the twenty-five, the mutation at 930, 614, 706 and 879 positions, lead to comparatively notable deviation in the structure of the protein and precisely add to the alterations in flexibility of the polypeptide chain. The resulting loss of flexibility may hamper host cell invasion too, either positively or negatively, as a cluster of mutations are housed in the S2 domain and involves the helices heptad repeat 1. There have been consistent efforts to study the mutation profile of SARS-CoV-2, after it spreads from Wuhan, China. The RBD (331 to 524 residues) of Spike glycoprotein is frequently mutated and various mutations have been mapped in this domain. Here, in this study we are reporting two additional mutations, R408I and E471Q found among the Indian isolates. Further, one of the mutations at the 614th position of the Spike glycoprotein (D614G) has gained considerable interest due to its rapid dominance worldwide and thus, may be a potential candidate responsible for making COVID-19 more virulent (Korber et al., 2020b) by making it resistant to proteolytic cleavage (Daniloski et al., 2020). It has also been hypothesized that the D614G mutation enables the RBD to acquire an open conformation that is better suited for its interaction with the host ACE2 (Bhattacharyya et al., 2020; Trucchi et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Therefore, the D614G variant is the most prominent strain already reported from various countries (Korber et al., 2020b). Our data also indicate that D614G is the dominant form among the Indian isolates, approximately 88% (134 out of 153) of the samples analysed in this study harbour this mutation (Fig. 1). Additionally, the molecular characterization of the mutations in Spike glycoprotein strongly indicates an emerging diversity among Indian isolates and, at the same time, raises concerns about the efficacy of diagnostics, prevention, and treatment measures against SARS-CoV-2.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Supplementary tables

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Gyanendra Bahadur Chand: Methodology, Visualization, editing manuscript.

Atanu Banerjee: Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft and & editing.

Gajendra Kumar Azad: Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft and & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Patna University, Patna, Bihar (India) for providing necessary infrastructural support. No funding was used to conduct this research.

References

- Ashok Kumar T. CFSSP: Chou and Fasman secondary structure prediction server. Wide Spectr. 2013 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.50733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya C., Das C., Ghosh A., Singh A.K., Mukherjee S., Majumder P.P., Basu A., Biswas N.K. 2020. Global Spread of SARS-CoV-2 Subtype with Spike Protein Mutation D614G is Shaped by Human Genomic Variations that Regulate Expression of TMPRSS2 and MX1 Genes. bioRxiv. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch B.J., van der Zee R., de Haan C.A.M., Rottier P.J.M. The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J. Virol. 2003 doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.16.8801-8811.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F.W., Yuan S., Kok K.H., To K.K.W., Chu H., Yang J., Xing F., Liu J., Yip C.C.Y., Poon R.W.S., Tsoi H.W., Lo S.K.F., Chan K.H., Poon V.K.M., Chan W.M., Ip J.D., Cai J.P., Cheng V.C.C., Chen H., Hui C.K.M., Yuen K.Y. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand G.B., Banerjee A., Azad G.K. Identification of novel mutations in RNA-dependent RNA polymerases of SARS-CoV-2 and their implications on its protein structure. PeerJ. 2020;8 doi: 10.7717/peerj.9492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniloski Z., Guo X., Sanjana N.E. 2020. The D614G Mutation in SARS-CoV-2 Spike Increases Transduction of Multiple Human Cell Types. bioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy S. Why are RNA virus mutation rates so damn high? PLoS Biol. 2018 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson A.E., Baase W.A., Zhang X.J., Heinz D.W., Blaber M., Baldwin E.P., Matthews B.W. Response of a protein structure to cavity-creating mutations and its relation to the hydrophobic effect. Science (80-. ) 1992 doi: 10.1126/science.1553543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung T.S., Liu D.X. Post-translational modifications of coronavirus proteins: roles and function. Futur. Virol. 2018 doi: 10.2217/fvl-2018-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung T.S., Liu D.X. Human coronavirus: host-pathogen interaction. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2019 doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-115759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goethe M., Fita I., Rubi J.M. Vibrational entropy of a protein: large differences between distinct conformations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015 doi: 10.1021/ct500696p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoret L.M., Sauer R.T. Tolerance of a protein helix to multiple alanine and valine substitutions. Fold. Des. 1998 doi: 10.1016/s1359-0278(98)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.H., Nitsche A., Müller M.A., Drosten C., Pöhlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber B., Fischer W.M., Gnanakaran S., Yoon H., Theiler J., Abfalterer W., Hengartner N., Giorgi E.E., Bhattacharya T., Foley B., Hastie K.M., Parker D.G. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber Bette, Fischer W., Gnanakaran S.G., Yoon H., Theiler J., Abfalterer W., Foley B., Giorgi E.E., Bhattacharya T., Parker M.D., Partridge D.G., Evans C.M., Silva T. de, LaBranche C.C., Montefiori D.C., Group, S.C.-19 G . 2020. Spike Mutation Pipeline Reveals the Emergence of a More Transmissible Form of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laamarti Meriem, Alouane T., Kartti S., Chemao-Elfihri M.W., Hakmi M., Essabbar A., Laamarti Mohamed, Hlali H., Allam L., Hafidi N. El, Jaoudi R. El, Allali I., Marchoudi N., Fekkak J., Benrahma H., Nejjari C., Amzazi S., Belyamani L., Ibrahimi A. 2020. Large Scale Genomic Analysis of 3067 SARS-CoV-2 Genomes Reveals a Clonal Geo-Distribution and a Rich Genetic Variations of Hotspots Mutations. bioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., Zhang Q., Shi X., Wang Q., Zhang L., Wang X. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F. Structure, function, and evolution of coronavirus spike proteins. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2016 doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N., Bi Y., Ma X., Zhan F., Wang L., Hu T., Zhou H., Hu Z., Zhou W., Zhao L., Chen J., Meng Y., Wang J., Lin Y., Yuan J., Xie Z., Ma J., Liu W.J., Wang D., Xu W., Holmes E.C., Gao G.F., Wu G., Chen W., Shi W., Tan W. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira F., Park Y.M., Lee J., Buso N., Gur T., Madhusoodanan N., Basutkar P., Tivey A.R.N., Potter S.C., Finn R.D., Lopez R. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus Hoffmann H.K.-W.S.P. Cell Press; 2020. A Multibasic Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 is Essential for Infection of Human Lung Cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachetti M., Marini B., Benedetti F., Giudici F., Mauro E., Storici P., Masciovecchio C., Angeletti S., Ciccozzi M., Gallo R.C., Zella D., Ippodrino R. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 mutation hot spots include a novel RNA-dependent-RNA polymerase variant. J. Transl. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02344-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan J., Deelder W., Ward D., Campino S., Hibberd M.L., Clark T.G. 2020. Controlling the SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak, Insights from Large Scale Whole Genome Sequences Generated Across the World. bioRxiv. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pires D.E.V., Ascher D.B., Blundell T.L. MCSM: predicting the effects of mutations in proteins using graph-based signatures. Bioinformatics. 2014 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues C.H.M., Pires D.E.V., Ascher D.B. DynaMut: predicting the impact of mutations on protein conformation, flexibility and stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018 doi: 10.1093/nar/gky300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi C., Alsafi Z., O’Neill N., Khan M., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C., Agha R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int. J. Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay M.Z., Poh C.M., Rénia L., MacAry P.A., Ng L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucchi E., Gratton P., Mafessoni F., Motta S., Cicconardi F., Bertorelle G., D\textquoterightAnnessa I., Di Marino D. 2020. Unveiling Diffusion Pattern and Structural Impact of the most Invasive SARS-CoV-2 Spike Mutation. bioRxiv. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walls A.C., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Qihui, Zhang Y., Wu L., Niu S., Song C., Zhang Z., Lu G., Qiao C., Hu Y., Yuen K.Y., Wang Qisheng, Zhou H., Yan J., Qi J. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.L., Abiona O., Graham B.S., McLellan J.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science (80-. ) 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.aax0902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.M., Wang W., Song Z.G., Hu Y., Tao Z.W., Tian J.H., Pei Y.Y., Yuan M.L., Zhang Y.L., Dai F.H., Liu Y., Wang Q.M., Zheng J.J., Xu L., Holmes E.C., Zhang Y.Z. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Jackson C.B., Mou H., Ojha A., Rangarajan E.S., Izard T., Farzan M., Choe H. 2020. The D614G Mutation in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Reduces S1 Shedding and Increases Infectivity. bioRxiv. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables