Abstract

Background

Cabozantinib improved progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS) and objective response rate (ORR) compared with everolimus in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) after prior antiangiogenic therapy in the phase III METEOR trial (NCT01865747). Limited data are available on the use of targeted therapies in older patients with advanced RCC.

Methods

Efficacy and safety in METEOR were retrospectively analysed for three age subgroups: <65 (n = 394), 65–74 (n = 201) and ≥75 years (n = 63).

Results

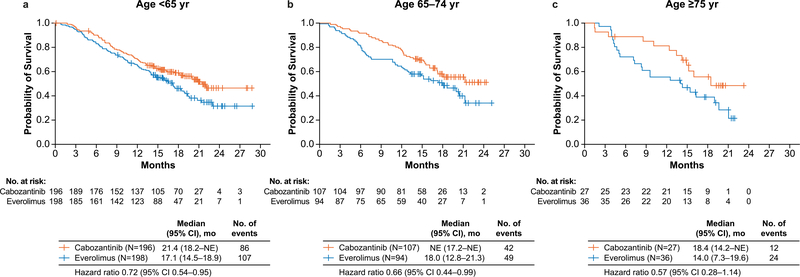

PFS, OS and ORR were improved with cabozantinib compared with everolimus in all age subgroups. The PFS hazard ratios (HRs) were 0.53 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.41–0.68), 0.53 (95% CI: 0.37–0.77) and 0.38 (95% CI: 0.18–0.79) for <65, 65–74 and ≥75 years, respectively, and the OS HRs were 0.72 (95% CI: 0.54–0.95), 0.66 (95% CI: 0.44–0.99) and 0.57 (95% CI: 0.28–1.14). The ORR for cabozantinib versus everolimus was 15% vs 5%, 21% vs 2% and 19% vs 0%, respectively. No significant differences were observed in PFS or OS with age as a categorical or continuous variable. Grade III/IV adverse events (AEs) were generally consistent across subgroups, although fatigue, hypertension and hyponatraemia occurred more frequently in older patients treated with cabozantinib. Dose reductions to manage AEs were more frequent in patients receiving cabozantinib than in those receiving everolimus. Dose reductions and treatment discontinuation due to AEs were more frequent in older patients in both treatment groups.

Conclusions

Cabozantinib improved PFS, OS and ORR compared with everolimus in previously treated patients with advanced RCC, irrespective of age group, supporting use in all age categories. Proactive dose modification and supportive care may help to mitigate AEs in older patients while maintaining efficacy.

Keywords: Age, Cabozantinib, Everolimus, METEOR, Renal cell carcinoma, Tyrosine kinase inhibitor, Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

1. Introduction

The incidence of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) increases with age, peaking in the seventies [1]. Older patients have more comorbidities and may have other age-related changes including reduced physiological reserves and changes in drug metabolism that can affect treatment course and outcomes [2,3]. Although the data are inconclusive on whether advanced age is a poor prognostic factor in RCC [4,5], treatment outcomes may vary depending on age [6]. Approximately half of the newly diagnosed kidney cancer cases occur in people aged ≥65 years, but this group represents only about a third of the study populations in pivotal phase III trials in advanced RCC [3]. Therefore, additional data on outcomes with available therapies based on age are needed to help guide treatment decisions.

Cabozantinib, an oral inhibitor of tyrosine kinases including MET, vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) and AXL [7], significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) and improved objective response rate (ORR) compared with everolimus in patients with advanced RCC after prior antiangiogenic therapy in the phase III METEOR trial [8,9]. In the present study, a retrospective analysis of efficacy and safety outcomes was conducted in the METEOR trial by three age categories.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients and treatment

METEOR is an international, randomised, open-label, phase III study that has been described in detail previously [8,9]. Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years with advanced or metastatic clear cell RCC and measurable disease as per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) version 1.1 [10]. Patients must have had previous treatment with at least one prior VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) and must have progressed within 6 months of their most recent treatment with VEGFR TKI and within 6 months of randomisation. A Karnofsky performance status of at least 70% and adequate organ function were required. Patients with clinically significant cardiovascular, gastrointestinal or infectious comorbidities were not eligible.

Patients were randomised 1:1 to cabozantinib (60 mg once daily) or everolimus (10 mg once daily). Randomisation was stratified by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) risk group [11] and the number of prior VEGFR TKIs (1 vs ≥ 2). Dose reductions were implemented to manage adverse events (AEs), with reductions to 40 mg and 20 mg for cabozantinib and 5 mg and 2.5 mg for everolimus. The study was conducted as per the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at each centre, and written informed consent was obtained for all patients.

2.2. Assessments

Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scans were collected at screening, every 8 weeks for the first 12 months and every 12 weeks thereafter. Safety was evaluated every 2 weeks for the first 8 weeks and every 4 weeks thereafter until treatment discontinuation. A follow-up visit occurred 30 days after the date of the decision to discontinue treatment. Patients were followed for OS every 8 weeks. Quality of Life (QoL) was measured using the validated patient self-reported questionnaire Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Kidney Symptom Index-19 item (FKSI-19) as described [12].

2.3. Data analysis

The primary end-point of PFS and secondary endpoints of OS, ORR and safety have been reported previously [8,9]. Demographics, efficacy and safety were retrospectively evaluated in age subgroups of <65, 65–74 and ≥75 years. Cut-offs of 65 and 75 years were selected to define the subgroups because 65 years is a commonly used age cut-off, and some studies have suggested that 75 years may be a more appropriate age for defining older populations [13,14]. Subgroup analyses of PFS, ORR and OS included all randomised patients; hazard ratios (HRs) are unstratified; confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values are considered descriptive with no adjustment for multiplicity. PFS analyses presented herein were assessed as per the independent radiology committee. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise QoL scores over time for each treatment arm. Safety was assessed in patients who received at least one dose of study treatment, and AEs were graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0. PFS, ORR and QoL were analysed with a data cut-off date of 22nd May 2015, and OS and safety were analysed with a data cut-off date of 31st December 2015.

PFS was defined as the time from randomisation to the earlier of radiographic progression as per RECIST version 1.1 [10] or death due to any cause. OS was defined as the time from randomisation to death from any cause. For each of the subgroups, the Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate median duration of PFS and OS, and HRs were estimated using a Cox regression model with the treatment group as the only independent variable. For ORR, p-values were calculated using the chi-square test. Objective response was defined as the proportion of patients with a confirmed complete or partial response as per RECIST version 1.1.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

A total of 658 patients were randomised from August 2013 to November 2014; 394 patients (60%) were aged <65, 201 (31%) were aged 65–74, and 63 (10%) were aged ≥75 years. Baseline characteristics in the three age subgroups were generally similar, including the percentage of patients with prior nephrectomy and tumour burden based on the location of metastatic sites and median target lesion sum of diameters (Table 1). For the prognostic MSKCC risk groups, a difference of >10% between the arms was observed for patients aged ≥75 years, with more patients with less favourable status in the everolimus arm. Importantly, risk groups based on International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) guidelines were relatively balanced between age subgroups and treatment arms. Across the age groups, the percentage of patients with less favourable Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) increased with age.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by age group.

| Age, <65 years |

Age, 65–74 years |

Age, ≥75 years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabozantinib (N = 196) | Everolimus (N = 198) | Cabozantinib (N = 107) | Everolimus (N = 94) | Cabozantinib (N = 27) | Everolimus (N = 36) | |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 57 (52–61) | 57 (50–60) | 68 (66–71) | 68 (66–71) | 78 (76–80) | 78 (76–79) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 150 (77) | 146 (74) | 82 (77) | 69 (73) | 21 (78) | 26 (72) |

| Female | 46 (23) | 51 (26) | 25 (23) | 25 (27) | 6 (22) | 10 (28) |

| Enrolment region, n (%) | ||||||

| Europe | 91 (46) | 87 (44) | 59 (55) | 52 (55) | 17 (63) | 14 (39) |

| North America | 74 (38) | 78 (39) | 36 (34) | 29 (31) | 8 (30) | 15 (42) |

| Asia Pacific | 26 (13) | 29 (15) | 11 (10) | 12 (13) | 2 (7.4) | 6(17) |

| Latin America | 5(3) | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Time since diagnosis to randomisation, years, median (IQR) | 2.4 (1.1–4.4) | 2.1 (1.0–4.8) | 3.6 (1.5–8.0) | 3.1 (1.7–7.0) | 3.8 (1.8–6.5) | 3.1 (1.7–7.6) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 136 (69) | 144 (73) | 75 (70) | 54 (57) | 15 (56) | 18 (50) |

| 1 | 60 (31) | 54 (27) | 32 (30) | 40 (43) | 12 (44) | 18 (50) |

| MSKCC risk group, n (%) | ||||||

| Favourable | 97 (49) | 99 (50) | 45 (42) | 38 (40) | 8 (30) | 13 (36) |

| Intermediate | 69 (35) | 73 (37) | 51 (48) | 44 (47) | 19 (70) | 18 (50) |

| Poor | 30 (15) | 26 (13) | 11 (10) | 12 (13) | 0 | 5(14) |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never | 74 (38) | 87 (44) | 46 (43) | 44 (47) | 16 (59) | 18 (50) |

| Former | 94 (48) | 84 (42) | 50 (47) | 43 (46) | 11 (41) | 16 (44) |

| Current | 28 (14) | 24 (12) | 9(8) | 7 (7) | 0 | 2 (6) |

| IMDC risk group, n (%) | ||||||

| Favourable | 39 (20) | 39 (20) | 23 (21) | 15 (16) | 4(15) | 8 (22) |

| Intermediate | 119 (61) | 121 (61) | 70 (65) | 68 (72) | 21 (78) | 25 (69) |

| Poor | 38 (19) | 38 (19) | 14 (13) | 11 (12) | 2 (7) | 3 (8) |

| Median target lesion SoD as per IRC, mm (IQR) | 66 (36–104) | 66 (42–111) | 66 (39–118) | 65 (43–102) | 62 (32–83) | 66 (33–117) |

| Metastatic sites as per IRC, n (%) | ||||||

| Lung | 118 (60) | 125 (63) | 68 (64) | 62 (66) | 18 (67) | 25 (69) |

| Liver | 45 (23) | 66 (33) | 36 (34) | 30 (32) | 7 (26) | 7 (19) |

| Lymph node | 133 (68) | 123 (62) | 59 (55) | 55 (59) | 14 (52) | 21 (58) |

| Bone | 47 (24) | 37 (19) | 23 (21) | 19 (20) | 7 (26) | 9 (25) |

| Prior therapy, n (%) | ||||||

| Nephrectomy | 171 (87) | 172 (87) | 90 (84) | 77 (82) | 22 (81) | 30 (83) |

| Number of VEGFR TKIs | ||||||

| 1 | 139 (71) | 140 (71) | 74 (69) | 65 (69) | 22 (81) | 24 (67) |

| ≥2 | 57 (29) | 58 (29) | 33 (31) | 29 (31) | 5(19) | 12 (33) |

| Sunitinib | 127 (65) | 125 (63) | 70 (65) | 58 (62) | 13 (48) | 22 (61) |

| Pazopanib | 85 (43) | 83 (42) | 45 (42) | 35 (37) | 14 (52) | 18 (50) |

| Axitinib | 34 (17) | 35 (18) | 14 (13) | 15 (16) | 4 (15) | 5(14) |

| Sorafenib | 10 (5) | 16 (8) | 8(7) | 10(11) | 3(11) | 5(14) |

| Nivolumab | 8 (4) | 8(4) | 8 (7) | 4 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (6) |

ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IMDC = International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium; IQR = interquartile range; IRC = independent radiology committee; MSKCC = Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; SoD = sum of diameters; TKI = tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VEGFR = vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

As of the data cut-off date for OS, the percentage of patients remaining on treatment was 21% (42/196) for cabozantinib versus 7.6% (15/198) for everolimus in patients aged <65 years, 28% (30/107) versus 7.4% (7/94) for patients aged 65–74 years and 7.4% (2/27) versus 8.3% (3/36) for patients aged ≥75 years. The median duration of follow-up for OS for surviving patients was 19.2 months (interquartile range [IQR]: 16.1–21.0) vs 18.9 months (IQR: 16.0–21.3), 18.6 months (IQR: 16.1–21.5) vs 18.6 months (IQR: 16.0–21.4) and 17.8 months (IQR: 15.9–20.1) vs 18.3 months (IQR: 15.1–20.8), respectively.

3.2. Efficacy

PFS was improved with cabozantinib compared with everolimus for all age subgroups (Fig. 1). The median PFS was 7.4 months with cabozantinib versus 3.8 months with everolimus for patients aged <65 (HR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.41–0.68), 8.1 versus 3.9 months for patients aged 65–74 (HR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.37–0.77) and 9.4 versus 4.4 months (HR: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.18–0.79) for patients aged ≥75 years.

Fig. 1. Progression-free survival by age group: (a) < 65 years, (b) 65–74 years, and (c) ≥75 years.

All randomised patients were included in the analyses. All hazard ratios are unstratified. CI = confidence interval; mo = months; NE = not estimable; PFS = progression-free survival; yr = year.

A higher ORR was observed with cabozantinib than with everolimus for the three age subgroups (Table 2). The ORR was 15% (95% CI: 11–21) with cabozantinib versus 5% (95% CI: 2–8) with everolimus for patients aged <65 years, 21% (95% CI: 13–29) versus 2% (95% CI: 0–7) for patients aged 65–74 years and 19% (95% CI: 6–38) versus 0 for patients aged ≥75 years. The results for objective responses as per investigator assessment also showed a higher ORR with cabozantinib than with everolimus (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2.

Tumour response as per the independent radiology committee.

| Age, <65 years |

Age, 65–74 years |

Age, ≥75 years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabozantinib (N = 196) | Everolimus (N = 198) | Cabozantinib (N = 107) | Everolimus (N = 94) | Cabozantinib (N = 27) | Everolimus (N = 36) | |

| Objective response rate, % (95% CI)a | 15 (11–21) | 5 (2–8) | 21 (13–29) | 2 (0–7) | 19 (6–38) | 0 |

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.007 | |||

| Best overall response, n (%) | ||||||

| Confirmed partial response | 30 (15) | 9(5) | 22 (21) | 2(2) | 5 (19) | 0 |

| Stable disease | 128 (65) | 113 (57) | 69 (64) | 66 (70) | 19 (70) | 24 (67) |

| Progressive disease | 30 (15) | 60 (30) | 11 (10) | 17 (18) | 0 | 11(31) |

| Not evaluable or missing | 8(4) | 16 (8) | 5(5) | 9(10) | 3(11) | 1 (3) |

CI = confidence interval.

All responses were partial responses.

Longer OS was observed with cabozantinib than with everolimus for the three age subgroups (Fig. 2). The median OS was 21.4 months with cabozantinib versus 17.1 months with everolimus (HR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.54–0.95) for patients aged <65 years, not reached versus 18.0 months for patients aged 65–74 years (HR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.44–0.99) and 18.4 versus 14.0 months (HR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.28–1.14) for patients aged ≥75 years. Systemic anticancer therapy was received by 57% of patients in the cabozantinib group versus 61% in the everolimus group among those aged <65 years, 36% versus 48% among those aged 65–74 years, and 52% versus 44% among those aged ≥75 years (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 2. Overall survival by age group: (a) < 65 years, (b) 65–74 years, and (c) ≥75 years.

All randomised patients were included in the analyses. All hazard ratios are unstratified. CI = confidence interval; mo = months; NE = not estimable; yr = year.

PFS and OS were analysed by Cox proportional hazard models using treatment group and age either as a continuous or categorical variable (<65, 65 to 74 and ≥75 years) (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Age was not a significant prognostic factor for PFS or OS in the analyses (p-values >0.05). Furthermore, interaction between the age groups and treatment was not significant.

3.3. Quality of life

The FKSI-19 questionnaire, which assesses disease-related symptoms, treatment side effects and function/well-being associated with advanced kidney cancer, was used to evaluate QoL in each of the subgroups [12]. Descriptive summaries of the FKSI-19 scores in each age subgroup are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. A clinically relevant difference could not be shown between treatment groups in each age subgroup based on an effect size ≥0.30 from repeated measures analyses [12] (Supplementary Table 5).

3.4. Safety

The median duration of exposure was 7.5 months with cabozantinib versus 5.4 months with everolimus for patients aged <65, 11.1 versus 3.9 months for patients aged 65–74, and 5.6 versus 3.7 months for patients aged ≥75 years (Table 3). Dose reductions were more common and implemented sooner in older patients, particularly for patients aged ≥75 years. Dose reductions were implemented in 118 (60%) cabozantinib-treated patients versus 42 (22%) everolimustreated patients among those aged <65, in 65 (61%) versus 25 (27%) patients among those aged 65–74 and in 23 (85%) versus 13 (36%) patients among those aged ≥75 years (Table 3). Discontinuation due to AEs was more common in older patients; 16 (8.1%) patients discontinued due to AEs in the cabozantinib arm versus 16 (8.3%) patients in the everolimus arm among those aged <65, 15 (14%) versus 13 (14%) among those aged 65–74 and 10 (37%) versus 5 (14%) among those aged ≥75 years. AEs leading to discontinuation in ≥2 patients in any treatment group are shown in Supplementary Table 6. A higher proportion of patients aged ≥75 years discontinued cabozantinib due to either fatigue or asthenia compared with younger patients (2 [7%] versus 2 [1%] for fatigue and 3 [11%] versus none for asthenia for patients aged ≥75 vs <65 years, respectively).

Table 3.

Study treatment exposure and dose reductions.

| Age, <65 years |

Age, 65–74 years |

Age, ≥75 years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabozantinib (N = 197) | Everolimus (N = 193) | Cabozantinib (N = 107) | Everolimus (N = 93) | Cabozantinib (N = 27) | Everolimus (N = 36) | |

| Duration of exposure, months, median (IQR) | 7.5 (4.2–14.6) | 5.4 (1.9–9.2) | 11.1 (6.5–14.8) | 3.9 (2.1–8.3) | 5.6 (3.5–13.7) | 3.7 (1.9–7.5) |

| Patients receiving dose reductions, n (%) | 118 (60) | 42 (22) | 65 (61) | 25 (27) | 23 (85) | 13 (36) |

| Average daily dose, mg, median | 44.6 | 9.4 | 41.6 | 8.9 | 33.6 | 8.1 |

| Time to first dose reduction, weeks, median (IQR) | 9.1 (5.3–18) | 9.6 (4.9–16) | 7.1 (5.1–14) | 9.1 (5.7–13) | 6.3 (5.1–9.7) | 8.3 (7.0–9.3) |

IQR = interquartile range.

The overall safety profiles of cabozantinib and everolimus were similar in all three age subgroups (Table 4), although toxicities generally increased with age. Older patients experienced a numerically higher incidence of some grade III/IV AEs than younger patients with cabozantinib. Grade III/IV AEs that differed by ≥10% between at least two age subgroups for cabozantinib-treated patients were hypertension (26 [13%] for those aged <65, 16 [15%] for those aged 65–75 and 7 [26%] for those aged ≥75 years), fatigue (16 [8%] for those aged <65, 12 [11%] for those aged 65–75 and 8 [30%] for those aged ≥75 years), asthenia (6 [3%] for those aged <65, 5 [5%] for those aged 65–75 and 4 [15%] for those aged ≥75 years) and hyponatraemia (4 [2%] for those aged <65, 6 [6%] for those aged 65–75, and 5 [19%] for those aged ≥75 years). The median time to first event is summarised for grade III/IV AEs that occurred at ≥8.0% in any treatment arm of the three age subgroups in Supplementary Table 7. The median time to first event was shorter in both treatment arms for diarrhoea, fatigue, hyponatraemia and asthenia in older patients (aged ≥75 years) than in younger patients (aged <65 years).

Table 4.

All-causality grade III/IV adverse events.

| Age, <65 years |

Age, 65–74 years |

Age, ≥75 years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabozantinib (N = 197) | Everolimus (N = 193) | Cabozantinib (N = 107) | Everolimus (N = 93) | Cabozantinib (N = 27) | Everolimus (N = 36) | |

| Any adverse event, n (%) | 134 (68) | 116 (60) | 80 (75) | 56 (60) | 21 (78) | 21 (58) |

| Diarrhoea | 27 (14) | 4 (2) | 13 (12) | 2 (2) | 3(11) | 1 (3) |

| Hypertension | 26 (13) | 3 (2) | 16 (15) | 6 (6) | 7 (26) | 3 (8) |

| Fatigue | 16(8) | 13 (7) | 12 (11) | 9(10) | 8 (30) | 2 (6) |

| PPE | 16(8) | 0 | 11 (10) | 3 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Anaemia | 10(5) | 28 (15) | 7 (7) | 17 (18) | 2 (7) | 8 (22) |

| Asthenia | 6 (3) | 4 (2) | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 4(15) | 1 (3) |

| Hyponatraemia | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 6 (6) | 3 (3) | 5(19) | 3 (8) |

| Hyperglycaemia | 0 | 9 (5) | 3(3) | 5 (5) | 0 | 2 (6) |

| Hypomagnesaemia | 8 (4) | 0 | 8 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypokalaemia | 8 (4) | 5 (3) | 7 (7) | 1 (1) | 1 (4) | 0 |

| Dyspnoea | 7 (4) | 8 (4) | 3 (3) | 5 (5) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Pneumonia | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 1(1) | 7 (8) | 0 | 2 (6) |

| Dehydration | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 5 (5) | 1 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Nausea | 8 (4) | 1 (1) | 5 (5) | 0 | 2 (7) | 0 |

| Mucosal inflammation | 2 (1) | 7 (4) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (7) | 2 (6) |

| Proteinuria | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (4) | 0 | 2 (7) | 0 |

| Syncope | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (7) | 0 |

| Lymphopenia | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (6) |

| Peripheral oedema | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (6) |

| Femoral neck fracture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6) |

| Pneumonitis | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 3 (3) | 0 | 2 (6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (6) |

Events that occurred at ≥5.0% frequency in either treatment arm for any age subgroup are summarised. Patients are counted once at the highest grade for each preferred term. The severity of adverse events was graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0).

PPE = palmar-plantar erythrodysaesthesia.

4. Discussion

The pivotal phase III METEOR trial showed that cabozantinib improved PFS, OS and ORR in patients with advanced RCC after prior antiangiogenic therapy [8,9]. This post hoc analysis reports outcomes for METEOR based on three age subgroups: <65, 65–74 and ≥75 years old.

Cabozantinib was associated with improved PFS, OS and ORR compared with everolimus in all three age subgroups. HRs for both PFS and OS were similar across the age subgroups, suggesting that the relative improvement with cabozantinib was maintained. Analyses of PFS and OS did not show a significant difference in outcomes based on age either as a continuous or categorical variable. Overall, the incidence of baseline characteristics associated with prognosis, such as prior nephrectomy [15], IMDC risk group [16] and presence of bone metastases [17], was similar across the age subgroups in this study, although a higher proportion of patients with more favourable ECOG PS was observed in the younger age subgroups. The consistency of these results across subgroups supports efficacy for cabozantinib in each age group.

Other targeted therapies have shown efficacy in both younger and older patients with advanced RCC, although the majority of the age analyses reported for pivotal trials are based on age groups of <65 and ≥65 years and report PFS and not OS [18–21]. In the Checkmate-025 trial comparing nivolumab and everolimus in previously treated patients, subgroup analyses of OS showed similar HRs for age groups of <65 and ≥65 years, suggesting improvement with nivolumab versus everolimus in both age groups [22], whereas the HR favoured everolimus over nivolumab for the subgroup of patients aged ≥75 years [23].

The overall safety profiles for cabozantinib and everolimus were similar in all three age subgroups. However, the incidence of all-causality grade III/IV events was higher with cabozantinib for patients aged ≥75 years than for younger patients. Events that occurred more frequently with cabozantinib in patients aged ≥75 years included fatigue, hypertension and hyponatraemia. Hypertension is a common on-target AE with VEGFR TKIs, associated with efficacy [24]. Median time to first grade III/IV AE in older patients was also shorter for some events in both treatment arms. Patients receiving cabozantinib more frequently had dose reductions to manage AEs than those receiving everolimus, with older patients receiving more dose reductions in both treatment groups. Discontinuation due to AEs was also more frequent for patients aged ≥75 years and was more frequent with cabozantinib than with everolimus in that age group. A higher incidence of grade III/IV AEs, dose reductions and discontinuations due to AEs in older patients than in younger patients has also been reported for other targeted therapies for RCC [25,26], which may be due to age-related physiological changes including differences in physiological reserves and pharmacokinetics [27]. In a population pharmacokinetics analysis, age was not considered to be a clinically significant covariate for cabozantinib clearance, although the possible effect of extreme age was not specifically explored [28]. Importantly, no new or unexpected toxicity occurred during treatment with cabozantinib. The recommended starting dose of cabozantinib for adults is 60 mg daily, irrespective of age [29]. With proactive dose modification, patient education and supportive care [30], AEs may be mitigated while retaining efficacy in elderly patients.

The study was not designed to determine outcomes for each age subgroup, and the small size of the subgroups increases the possibility of chance results. Many other studies have used two age subgroups with a cut-off of 65 years [18–22], corresponding to the median age of patients with advanced RCC. In this analysis, three age subgroups were used to better determine outcomes within different age categories and because some studies have suggested that 75 years may be a more appropriate cut-off than 65 years to define older populations [13,14]. Eligibility criteria for this study, similar to the majority of clinical trials, restricted enrolment to those without significant comorbidities, and the study population in this trial may be healthier on average than those encountered in the clinic. Nonetheless, the results suggest that cabozantinib improves efficacy outcomes compared with everolimus in each age category. The analyses presented here are exploratory, and a larger prospective trial would be needed to better define outcomes with cabozantinib based on age.

5. Conclusions

Treatment with cabozantinib improved PFS, OS and ORR in patients with advanced RCC compared with everolimus in all age subgroups in this retrospective analysis, supporting the use of cabozantinib in all age categories. However, older patients more frequently discontinued or required dose reductions due to AEs. Older patients may benefit from proactive dose modification and supportive care to mitigate AEs while retaining efficacy. Additional studies are needed to better define outcomes with cabozantinib based on age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients, their families, the investigators and site staff, and the study teams participating in this trial. Medical writing support was provided by Julie C. Lougheed, PhD (Exelixis, Inc.), with editorial assistance by Fishawack Communications Inc. (Conshohocken, PA, USA), which was funded by Exelixis. Patients treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center were supported in part by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support grant/core grant (P30 CA008748).

6. Funding and role of the sponsor

This work was supported by Exelixis, Inc. (Alameda, CA, USA). The sponsor was involved in design and conduct of the study as well as in collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data in collaboration with the authors.

Conflict of interest statement

F.D. certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (e.g. employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony royalties or patents filed, received or pending), are the following: F.D. received research grant support from Pfizer, Novartis, Ipsen, and Health Research Foundation of Central Denmark Region, outside the submitted work. R.J.M. served in a consultancy or advisory role for Pfizer, Novartis, Merck, Genentech/Roche, Eisai and Exelixis and received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Genentech/Roche, Eisai, Exelixis and Novartis. K.C. received honoraria from Roche, served in a consultancy or advisory role for Roche and Novartis and received support for travel and accommodation from Roche and Amgen. S.N. received honoraria from Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Ipsen and Eusa Pharma, outside the submitted work. I.C. and A.C. are employees of Exelixis. B.E. received grant support and personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Novartis, Ipsen and Eusa. S.P. received honoraria from Astellas Pharma, Medivation and Novartis, served in a consultancy or advisory role for Aveo, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, Genentech, Myriad Pharmaceuticals, Novartis and Pfizer and received research funding from Medivation. T.P. served in a consultancy or advisory role for AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, Merck and Novartis, and received research funding from AstraZeneca/MedImmune and Roche/Genentech. T.K.C. served in a consultancy or advisory role for Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Peloton, Pfizer, EMD Serono, Prometheus Laboratories, Corvus, Ipsen, UpToDate, NCCN and Analysis Group, received research funding (institutional and personal) from AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Cerulean, Eisai, Foundation Medicine Inc., Exelixis, Ipsen, Tracon, Genentech, Roche, Roche Products Limited, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Peloton, Pfizer, Prometheus Laboratories, Corvus, Calithera, Analysis Group and Takeda, received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Alexion, Sanofi/Aventis, Bayer, BMS, Cerulean, Eisai, Foundation Medicine Inc., Exelixis, Genentech, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Peloton, Pfizer, EMD Serono, Prometheus Laboratories, Corvus, Ipsen, UpToDate, NCCN, Analysis Group, NCCN, Michael J. Hennessy (MJH) Associates, Inc (Healthcare Communications Company with several brands such as OncLive and PER), Lpath, Kidney Cancer journal, Clinical Care Options, PlatformQ, Navinata Healthcare, Harborside Press, American Society of Medical Oncology, NEJM, Lancet Oncology and Heron Therapeutics and has received travel, accommodations and expenses in relation to consulting and advisory roles or honoraria; T.K.C.’s institution (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) may have received additional independent funding or royalties from drug companies potentially involved in research around the subject matter. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Appendix A Supplementary Data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2019.10.032.

References

- [1].Znaor A, Lortet-Tieulent J, Laversanne M, Jemal A, Bray F. International variations and trends in renal cell carcinoma incidence and mortality. Eur Urol 2015;67(3):519–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “silver tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 2016;25(7):1029–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kanesvaran R, Saux OL, Motzer R, Choueiri TK, Scotte F, Bellmunt J, et al. Elderly patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: position paper from the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. Lancet Oncol 2018;19(6):e317–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Scoll BJ, Wong YN, Egleston BL, Kunkle DA, Saad IR, Uzzo RG. Age, tumor size and relative survival of patients with localized renal cell carcinoma: a surveillance, epidemiology and end results analysis. J Urol 2009;181(2):506–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Verhoest G, Veillard D, Guille F, De La Taille A, Salomon L, Abbou CC, et al. Relationship between age at diagnosis and clinicopathologic features of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2007; 51(5):1298–304. discussion 1304–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Vogelzang NJ, Pal SK, Ghate SR, Swallow E, Li N, Peeples M, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes in elderly advanced renal cell carcinoma patients starting pazopanib or sunitinib treatment: a retrospective Medicare claims analysis. Adv Ther 2017;26(10): 017–0628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yakes FM, Chen J, Tan J, Yamaguchi K, Shi Y, Yu P, et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther 2011;10(12):2298–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, Tannir NM, Mainwaring PN, Rini BI, et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma (METEOR): final results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17(7): 917–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, Mainwaring PN, Rini BI, Donskov F, et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015;373(19):1814–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45(2): 228–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwartz LH, Reuter V, Russo P, Marion S, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in previously treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2004;22(3): 454–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cella D, Escudier B, Tannir NM, Powles T, Donskov F, Peltola K, et al. Quality of life outcomes for cabozantinib versus everolimus in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: METEOR phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(8): 757–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pal SK, Hsu J, Hsu S, Hu J, Bergerot P, Carmichael C, et al. Impact of age on treatment trends and clinical outcome in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Geriatr Oncol 2013; 4(2):128–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nishijima TF, Muss HB, Shachar SS, Moschos SJ. Comparison of efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) between younger and older patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev 2016;45:30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hanna N, Sun M, Meyer CP, Nguyen PL, Pal SK, Chang SL, et al. Survival analyses of patients with metastatic renal cancer treated with targeted therapy with or without cytoreductive nephrectomy: a national cancer data base study. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(27):3267–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Harshman LC, Bjarnason GA, Vaishampayan UN, et al. External validation and comparison with other models of the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic model: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2013;14(2):141–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].McKay RR, Lin X, Perkins JJ, Heng DY, Simantov R, Choueiri TK. Prognostic significance of bone metastases and bisphosphonate therapy in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2014;66(3):502–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007;356(2): 115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pal SK, Vanderwalde A, Hurria A, Figlin RA. Systemic therapies for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in older adults. Drugs Aging 2011;28(8):635–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, Kaprin A, Szczylik C, Hutson TE, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;378(9807):1931–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, Szczylik C, Lee E, Wagstaff J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(6):1061–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Escudier B, Sharma P, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, et al. CheckMate 025 randomized phase 3 study: outcomes by key baseline factors and prior therapy for nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2017;72(6):962–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015;373(19):1803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Donskov F, Michaelson MD, Puzanov I, Davis MP, Bjarnason GA, Motzer RJ, et al. Sunitinib-associated hypertension and neutropenia as efficacy biomarkers in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients. Br J Cancer 2015;113(11):1571–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Eisen T, Oudard S, Szczylik C, Gravis G, Heinzer H, Middleton R, et al. Sorafenib for older patients with renal cell carcinoma: subset analysis from a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100(20):1454–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hutson TE, Bukowski RM, Rini BI, Gore ME, Larkin JM, Figlin RA, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in elderly patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2014;110(5):1125–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Li D, Yuan Y, Lau YM, Hurria A. Functional versus chronological age: geriatric assessments to guide decision making in older patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol 2018;19(6):e305–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lacy S, Yang B, Nielsen J, Miles D, Nguyen L, Hutmacher M. A population pharmacokinetic model of cabozantinib in healthy volunteers and patients with various cancer types. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2018;81(6):1071–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].CABOMETYX United States Prescribing information. January 2019.

- [30].Storbjerg B, Donskov F. Living with advanced kidney cancer and treatment with cabozantinib: through the eyes of the patient and the physician. Oncol Ther 2018;6:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.