Abstract

Background

Following a reduction in global child mortality due to communicable diseases, the relative contribution of congenital anomalies to child mortality is increasing. Although infant survival of children born with congenital anomalies has improved for many anomaly types in recent decades, there is less evidence on survival beyond infancy. We aimed to systematically review, summarise, and quantify the existing population-based data on long-term survival of individuals born with specific major congenital anomalies and examine the factors associated with survival.

Methods and findings

Seven electronic databases (Medline, Embase, Scopus, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ProQuest Natural, and Biological Science Collections), reference lists, and citations of the included articles for studies published 1 January 1995 to 30 April 2020 were searched. Screening for eligibility, data extraction, and quality appraisal were performed in duplicate. We included original population-based studies that reported long-term survival (beyond 1 year of life) of children born with a major congenital anomaly with the follow-up starting from birth that were published in the English language as peer-reviewed papers. Studies on congenital heart defects (CHDs) were excluded because of a recent systematic review of population-based studies of CHD survival. Meta-analysis was performed to pool survival estimates, accounting for trends over time. Of 10,888 identified articles, 55 (n = 367,801 live births) met the inclusion criteria and were summarised narratively, 41 studies (n = 54,676) investigating eight congenital anomaly types (spina bifida [n = 7,422], encephalocele [n = 1,562], oesophageal atresia [n = 6,303], biliary atresia [n = 3,877], diaphragmatic hernia [n = 6,176], gastroschisis [n = 4,845], Down syndrome by presence of CHD [n = 22,317], and trisomy 18 [n = 2,174]) were included in the meta-analysis. These studies covered birth years from 1970 to 2015. Survival for children with spina bifida, oesophageal atresia, biliary atresia, diaphragmatic hernia, gastroschisis, and Down syndrome with an associated CHD has significantly improved over time, with the pooled odds ratios (ORs) of surviving per 10-year increase in birth year being OR = 1.34 (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.24–1.46), OR = 1.50 (95% CI 1.38–1.62), OR = 1.62 (95% CI 1.28–2.05), OR = 1.57 (95% CI 1.37–1.81), OR = 1.24 (95% CI 1.02–1.5), and OR = 1.99 (95% CI 1.67–2.37), respectively (p < 0.001 for all, except for gastroschisis [p = 0.029]). There was no observed improvement for children with encephalocele (OR = 0.98, 95% CI 0.95–1.01, p = 0.19) and children with biliary atresia surviving with native liver (OR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.88–1.03, p = 0.26). The presence of additional structural anomalies, low birth weight, and earlier year of birth were the most commonly reported predictors of reduced survival for any congenital anomaly type. The main limitation of the meta-analysis was the small number of studies and the small size of the cohorts, which limited the predictive capabilities of the models resulting in wide confidence intervals.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis summarises estimates of long-term survival associated with major congenital anomalies. We report a significant improvement in survival of children with specific congenital anomalies over the last few decades and predict survival estimates up to 20 years of age for those born in 2020. This information is important for the planning and delivery of specialised medical, social, and education services and for counselling affected families. This trial was registered on the PROSPERO database (CRD42017074675).

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Svetlana V. Glinianaia and colleagues report on temporal trends in long-term survival of children born with specific congenital anomalies.

Author summary

Why was this study done?

Following a reduction in global child mortality due to communicable diseases, the relative contribution of congenital anomalies to child mortality under age 5 years is increasing globally.

Identifying and addressing the emerging priority of congenital anomalies, including for children aged 5–9 years, is one of the strategic directions for the post-2015 child health agenda.

This research aimed to summarise and quantify the existing population-based evidence on long-term survival of children born with specific major congenital anomalies that manifest in childhood.

What did the researchers do and find?

This systematic review included 55 international studies that estimated survival beyond 1 year of age of children born with major congenital anomalies.

Our meta-analysis results of 41 studies over the birth years 1970–2015 showed a statistically significant improvement in survival over time in children with spina bifida, oesophageal atresia, biliary atresia, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, gastroschisis, and Down syndrome associated with a congenital heart defect, but there was no evidence of improvement in those with encephalocele or biliary atresia with a native liver.

The commonest significant independent predictors of reduced survival for any congenital anomaly type were presence of additional structural anomalies, low birth weight, and earlier birth year period.

What do these findings mean?

A significant improvement in survival of children with specific congenital anomalies over the last few decades reported by individual studies and identified by the meta-analysis has important public health, medical, social, and family implications.

Information on predicted survival of children with congenital anomalies up to 20 years of age is important for planning specialised medical, social, and education services for these children and for estimating costs associated with special care needs in childhood and adulthood.

Introduction

Globally, mortality in children aged under 5 years has halved since 1990, mainly because of a sharp reduction in deaths from communicable diseases as a result of targeted child health strategies and interventions of the United Nations (UN) Millennium Development Goals [1]. Following this worldwide reduction, the relative contribution of congenital anomalies to child mortality is increasing globally and is therefore outlined as an emerging priority to be addressed by the UN Sustainable Development Goals in the post-2015 child health agenda [2]. Although the contribution of congenital anomalies to infant mortality is well described, in particular for developed countries [3–5], there is less research focused on survival beyond the first year of life. However, this is of considerable public health importance, as according to evidence from North America and Europe, the mortality rate of individuals born with congenital anomalies significantly exceeds that of the general population after infancy as well [6–9]. In addition, a large variation in child death rates still exists between countries, even within Europe [10]. In 2012, the child death rates (age 0–14 years) were about 60% higher in the United Kingdom and Belgium compared to Sweden, with an additional 10 Western European countries being 30% higher than Sweden [10]. Currently, a quantitative summary of population-based studies of survival beyond infancy for specific congenital anomalies is lacking. Accurate estimates of long-term survival are important for clinicians counselling parents when a congenital anomaly is diagnosed pre- or postnatally and for public health commissioners to ensure adequate resources are in place to provide high-quality medical and social care for these individuals. Importantly, it is essential that estimates are provided according to type of congenital anomaly, given the diversity in aetiology, treatment, and prognosis.

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to summarise and quantify the existing population-based data on long-term survival (beyond infancy) of individuals born with specific major congenital anomalies that manifest in childhood and explore the risk factors associated with survival.

Methods

Search strategy

This study is reported as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline (S1 PRISMA Checklist). A protocol for this systematic review was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (CRD42017074675) (S1 Text). We conducted comprehensive literature searches using a combination of the following sources of information:

Electronic bibliographical databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ProQuest Natural, and Biological Science Collections and also the databases of the systematic reviews, i.e., PROSPERO, the JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. We used key words and subject headings (dependent on the database) combining the keywords for the population (birth, pregnancy, delivery), exposure (congenital anomaly, including specific anomaly groups), outcome (long-term survival, mortality), and study design (population-based studies), incorporating elements of the PICOS (Population/Patient, Intervention/Exposure, Comparator group, Outcome, Study design) framework into our systematic search strategy [11] (S1 Table). The final search results were limited to English papers and to humans, whereas the initial searches had no language limitations to examine whether there were any relevant studies we could have missed. We have identified 66 papers published in non-English language (79% from Europe) based on Medline search, but no papers met our inclusion criteria.

Manual searching of the reference lists of the included full papers and of the relevant previous literature reviews, including systematic, was performed.

Citation searching for studies that had referenced the included studies was performed via the Google Scholar citation function.

Keyword searches in key journals, including Birth Defects Research, Archives of Disease in Childhood, Pediatrics, The Journal of Pediatrics, and Journal of Pediatric Surgery, were also undertaken.

Authors were contacted if there was insufficient information to decide whether the study met the inclusion criteria or if additional information for the inclusion in the meta-analysis was needed.

Reference lists and citations of any new articles identified were further searched for any additional studies in the iterative process until no new studies were identified. Database searches were completed in March 2019 and updated in May 2020.

SVG conducted all searches and screened the titles and abstracts of all the identified records according to the inclusion criteria, and three other authors (MS, AC, JR) independently screened a random 10% sample of the records using the Rayyan software for systematic reviews [12]. Any discrepancies (n = 4) in the included studies were discussed amongst all authors and agreement reached.

Definitions and classification of congenital anomalies

Major congenital anomalies in the included studies were classified according to the International Classification of Disease (ICD) revision 8 (ICD-8) [8], ICD-9 (majority of papers), ICD-10 [13–15], and British Paediatric Association (BPA-ICD-9) diagnosis coding [16–20] or surgical codes [21]. Some papers that included a long birth year period used more than one ICD version for the corresponding time periods [9,22–25]. The included studies reported the survival estimates for all congenital anomalies combined (e.g., ICD-9 codes 740.0–759.9) and/or by congenital anomaly group (the system affected, e.g., urinary system, ICD-9 753.0–753.9) and/or subtype (the individual disorder, e.g., spina bifida, ICD-9 741). Some European studies [14,15,17] classified major congenital anomalies according to European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies (EUROCAT) guidelines [26,27]. We have presented the congenital anomaly subtypes within the major congenital anomaly groups according to the EUROCAT classification [26].

Eligibility criteria

Studies meeting the following criteria were included: (1) being an original population-based peer-reviewed study that reported long-term (beyond 1 year of life) survival of children born with a major congenital anomaly that manifests in childhood; (2) reporting survival probability (or the number of patients born and the number or proportion alive at age >1 year) for these children that were followed up from birth; (3) being published from 1 January 1995 to 30 April 2020 to increase comparability of included birth cohorts in relation to medical care and treatment availability/policies; (4) involving humans only and published in the English language.

Studies were excluded if (1) they reported survival during the first year of life only; (2) patients were not followed up from birth, because this may have under-ascertained deaths occurring prior to follow-up (e.g., if follow-up began after surgical correction); (3) they were not population-based, as other study designs are more likely to incur ascertainment bias (e.g., hospital-based studies may capture more severe phenotypes); (4) they focused on individuals born with congenital heart defect (CHD), because there was a recently published systematic review covering these population-based studies [28]; (5) they followed up a restricted subgroup of patients (e.g., preterm births only or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO] patients only). No exclusions were made based on the birth year of studied cohorts.

Data extraction

Information on the following study characteristics was extracted: study location, birth year period, duration of follow-up/years of survival, congenital anomaly type and if isolated/non-isolated, sources of case ascertainment (e.g., congenital anomaly register) and sources of death identification (e.g., linkage with a mortality database), number of cases and deaths, Kaplan-Meier survival estimates reported, or the survival estimates calculated by the reviewers. Authors were contacted if survival estimates were reported for subgroups of patients only (e.g., by sex or age at operation), if it was not possible to calculate 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) or extract survival estimates from the Kaplan-Meier curves, or if further information was required or clarification needed (n = 18). If the authors did not respond after two reminders or if the study was closed and access to the data was not possible, we calculated the lower and upper limits of the 95% CI according to the efficient-score method (corrected for continuity) described by Newcombe, 1998 [29], based on the procedure outlined by Wilson, 1927 [30] (http://www.vassarstats.net/survival.html). If survival estimates were not reported in the text or tables of the included paper, they were extracted from Kaplan-Meier survival curves, where available, using PlotDigitizer software [31]. If none of the above was possible, the study was excluded.

Data extraction and quality appraisal of the included studies were performed in duplicate, i.e., all by SVG and a subset of studies by each coauthor. Data were entered into piloted data extraction forms (S2 Table).

Statistical analysis

Where three or more articles reported survival with the number of births (or where the numbers of births could be estimated from the 95% CIs provided) for a specific congenital anomaly, a meta-analysis was performed to estimate pooled survival at ages 1, 5, 10, and 20 (and 25, where available) years. The Stata program “gllamm” was used to fit univariate multilevel meta-analysis of longitudinal data to allow for the correlations in survival over several time periods within studies [32,33]. Survival according to age (0–25 years) was modelled using the logistic regression options within the gllamm program: family(binomial) and link(logit). The outcome of interest was the number of deaths occurring out of the total number of live births. The number of deaths at each time point, if not provided, was estimated from the published proportions surviving and the number of live births by assuming there was no loss to follow-up. Calculating the number of deaths in this way will be unbiased (as the proportion surviving is unbiased) but will result in slightly too narrow confidence intervals. To confirm that this is valid, an alternative method using the arcsine square root transformation [34] of the published survival estimate was applied and the estimated standard error was calculated, and a model was fitted in gllamm using the weighted regression options instead of the logistic regression above. Both methods reported consistent results, and hence, the results of the logistic regression models are reported here, as they enable the interpretation of the odds of increasing survival over time. Studies were treated as a random effect and cohort of birth and age at survival as fixed effects nested within the studies. Age was modelled as a continuous variable using a linear term or, where significant (according to a likelihood ratio test), a quadratic term. Cohort of birth was modelled as a continuous variable. Most included studies reported survival across distinct periods (e.g., between 2000 and 2009), so the mean year of birth was used (e.g., 2005). For studies that reported survival estimates for multiple cohorts (e.g., 2000–2004, 2005–2009), survival for both cohorts were entered into the model, again with average year of birth for each cohort (e.g., 2002 and 2007). Using the models, survival at ages 1, 5, 10, 20, and 25 years was estimated for patients born in 2000 and 2020. Models were fitted separately for each type of congenital anomaly. Odds ratios (ORs) representing the increase/decrease in survival per 10-year increase in time were extracted from the models. Where fewer than three studies reported survival for a specific congenital anomaly, the survival estimates were discussed narratively. The ages for which more than three studies reported a survival rate were plotted separately; often, the reports were at 5 or 10 years of age. This allows the reader to evaluate the changes that have occurred over time in the survival of the children up to 5 years of age and separately up to 10 years of age. All modelled survival curves, although plotted on two separate figures, are derived from the one model fitted on all the data.

Analysis was performed in Stata 15 (StataCorp), and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Quality appraisal

The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) for cohort studies [35] was used to assess the quality of the included studies. The scale assesses information bias, selection bias, and confounding (S2 Table). Although a traditional cohort study can be awarded a maximum of nine stars, for survival population-based studies a comparison group is not a mandatory component of the study design; therefore, a maximum of six stars can be allocated to the majority of the included studies (S3 Table).

Results

Search results

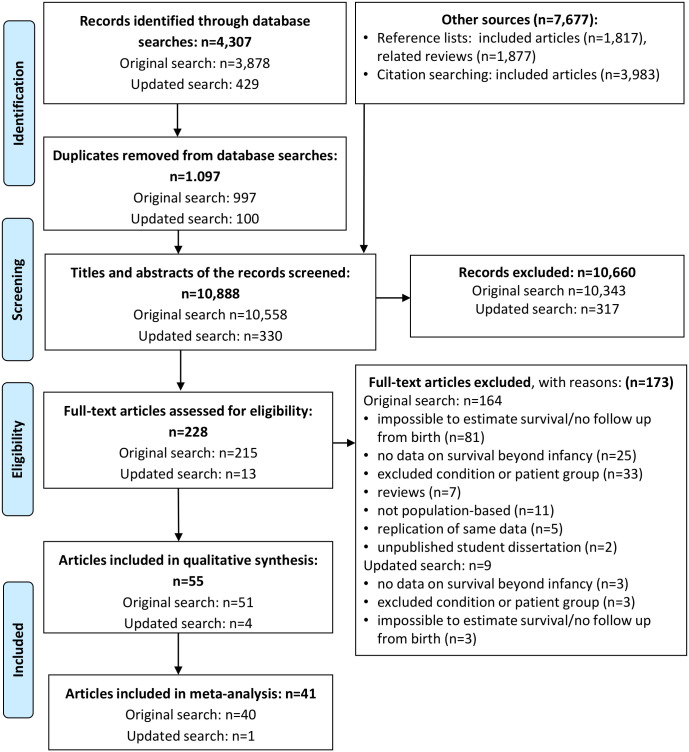

A total of 10,888 records identified from the electronic database searches and other sources were available for screening titles and abstracts (Fig 1). After excluding 10,660 records, 228 were eligible for full text review. After further exclusion of 173 articles, 55 met the inclusion criteria, covering a total population of 367,801 live births with various types of major congenital anomalies. Earlier follow-up studies based on the same population were replaced by more recent ones if they also reported survival at a younger age (n = 2 [36,37]). However, if survival at a more advanced age only was reported in the later article [38], the earlier article was also included (n = 1 [39]).

Fig 1. PRISMA flowchart of searches, screening, and study selection.

PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 provides the description of 55 studies included in this review. Further detail on the sources of case ascertainment and death identification and the description of the comparison group, if any, are given in S4 Table. Nine studies analysed long-term survival of all congenital anomalies combined: seven with [6,8,15,17,40–42] and two without [7,43] stratification by congenital anomaly group/subtype (Table 1). Other studies (n = 46) focused on specific groups or subtypes of congenital anomalies: the central nervous system (n = 5 [44–49]), including spina bifida [44–46,48,49] and encephaloсele [44,47]; orofacial clefts (n = 1 [16]); anomalies of the digestive system (n = 22), including oesophageal atresia [9,50,51], anorectal malformations [52], congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) [18,23,51,53,54], biliary atresia [36–39,55–64], and Hirschsprung disease [24]; abdominal wall defects (n = 1 [21]); chromosomal anomalies (n = 12), including trisomy 21 [14,19,22,65–69,70,71], trisomy 13 [25,72], and trisomy 18 [25,72]; skeletal dysplasias (n = 2 [13,20]); and Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) (n = 1 [73]). The included studies were conducted in Europe (n = 29 [8,9,13–15,17,21–24,36–39,44,45,50–54,56–58,60,61,64,65,68]), the United States of America (n = 12 [7,18–20,40,41,43,46–48,70,72]), Australia (n = 7 [16,42,59,66,67,69,73]), Canada (n = 3 [6,25,63]), Japan (n = 1 [62]), Brazil (n = 1 [55]), and Hong Kong (n = 1 [71]). One international study reported survival of children with spina bifida from a number of registries from Europe and the USA [49]. As all included studies were population-based, sources of case ascertainment for most studies (n = 39) were congenital anomaly registers or surveillance programmes that either included all types of major congenital anomalies or were anomaly-specific. The majority of these studies linked their congenital anomaly data with death registration data to ascertain data on age at death (S4 Table).

Table 1. Description of included studies.

| Author, publication year, reference, location | Congenital anomaly (CA) group/subtype | Birth year period | Duration and completeness of follow-up (FU) | Inclusion of additional anomalies/exclusions | Reporting of survival estimates | Study quality total score* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agha, 2006 [6], Ontario, Canada | All anomalies and by group | 1979–1986 | 10 years for all anomalies | Multiple births excluded | 1- and 5-year estimates by CA group reported, 10-year survival for all CAs extracted from Kaplan-Meier (K-M) curves | 9 |

| Bakker, 2019 [49], 5 European and 4 USA registries‡ | Spina bifida International Classification of Diseases Revision 10 (ICD-10) Q05 and ICD-9 741 | 2001–2012 (for 7 out of 8 included registers) | Up to 5 and ≥5 years, depending on the registry | Only registries with FU beyond 1 year and using linkage to vital records (n = 9) are included in this review. Cases excluded when present with anencephaly. Both isolated and syndromic cases are included | Survival estimates calculated using mortality rates reported | 6 |

| Bell, 2016 [16], Western Australia (WA) | Orofacial clefts | 1980–2010 | FU to 20 years for 1980–1992, low loss to FU (approximately 2.8%) | Estimates for isolated and those with additional CA | 1-year estimates by cleft type (for 1980–2010 cohort) and 20-year estimates (for 1980–1992) reported | 8 |

| Berger, 2003 [7], Michigan, USA | All anomalies (not stratified by group) | 1992–1998 | Up to 7 complete years of FU (for those born in 1992, 97%) | Multiple births excluded | Reported mortality for each birth year, survival estimated by reviewer | 8 |

| Borgstedt-Bakke, 2017 [45], western Denmark | Spina bifida (myelomeningocele) | 1 Jan 1970 to 30 Jun 2015 | Up to 20 years, censored on 9 Nov 2015; median age at death: 1 year of age | Excluded cases with incomplete mortality or clinical data (n = 16) | Survival estimates extracted from K-M curves by birth year period: 1970–1979, 1980–1989, and 1990–2015 | 7 |

| Brodwall, 2018 [22], Norway | Down syndrome (DS) | 1994–2009 | Complete FU to 5 years for those traced (5.5% lost to FU—censored) | Isolated DS and with associated (congenital heart defect [CHD] and/or extracardiac malformation) anomalies included | K-M survival estimates reported in the paper or obtained from authors on request | 8 |

| Burgos, 2017 [23], Sweden | Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) | 1987–2013 | FU up to 20 years for the whole period, up to 10 years for 2000–2013, complete for 98.7% | Patients who were diagnosed of CDH after the neonatal period were excluded | 1-year and overall (beyond 1 year) mortality reported; 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival extracted from K-M curves | 6 |

| Cassina, 2016 [50], Northeast Italy (NEI) | Oesophageal atresia (ICD-9 750.3) | 1981 to 31 July 2012 | FU up to age 25 years (minimum 3 months) or censored at 31 Oct 2012, survival traced in 91.7% (330/360) | Chromosomal anomalies (n = 42, 10.3%) excluded, other non-isolated cases included | Survival estimates reported for 1 and 25 years, for 5 and 10 years extracted from K-M curves | 6 |

| Cassina, 2019 [52], NEI | Anorectal malformations | 1981–2014 | Survival status was traced for patients born between 1 Jan 1990 and 31 Jul 2012 up to 20 years (88.2%) | Those with non-isolated anomalies were included (n = 216, 50.5%), isolated (n = 212) included 7 patients with trisomy 21 | Overall K-M survival estimates (with 95% confidence interval [95% CI]) reported for 1 and 20 years, for 10 years separately for isolated and non-isolated | 5 |

| Chardot, 2013 [36], France | Biliary atresia (BA) | 1986–2009 | Median FU in survivors 9.5 years (range 3 months to 24.6 years) | Only cases with corrected diagnosis of BA, including those with BA splenic malformation syndrome (BASM) | K-M survival estimates reported for 5, 10, 15, and 20 years, 95% CI calculated using reported SE | 6 |

| Chua, 2020 [71], Hong Kong | DS (ICD-9 code 758.0) | 1995–2014 | FU from birth until the age of 5 years, up to 30 Jun 2017, or the date of death (FU range 0.01–22.0 years) | All with DS, with or without associated anomalies | K-M survival estimates reported for 6 months, 1 and 5 years | 6 |

| Dastgiri, 2003 [17], Glasgow, Scotland | All anomalies and by group | 1980–1997 | 5 years’ FU for all (97% complete) | Isolated anomalies only included | K-M survival estimates reported for 1 and 5 years and 95% CI provided by authors on request | 6 |

| Davenport, 2011 [37], England and Wales | BA | 1999–2009 | Vital status assessed in Jan 2010—up to 10 years of age, none lost to FU | BA cases with BASM and other associated anomalies (n = 84) included | Actuarial survival estimates reported for 5 and 10 years, extracted from survival curve for 4 years | 6 |

| De Carvalho, 2010 [55], Brazil | BA | Jul 1982 to Dec 2008 | FU between Jul 1982 and Dec 2008, loss to FU not reported | BA cases with BASM or other associated anomalies (n = 61) included | K-M survival estimates (without 95% CI) reported for 4 years | 5 |

| De Vries, 2011 [56], the Netherlands | BA | 1977–1988 | 20-year FU: median 23.8 (range 20.2–31.4), 2 lost to FU | All BA cases (including BASM, n = 7) included, no other anomalies reported | 20-year survival reported | 6 |

| Eide, 2006 [8], Norway | All anomalies and by selected subgroup | 1967–1979; FU 1967–1998 | FU 18 years for all birth years, 6.2% (n = 24,355) untraceable from the whole cohort of 393,570 | Male patients and live singleton births only included. CAs ascertained during the first week after birth only, selection bias possible | No survival analysis performed, mortality by age 18 years (military draft) reported, survival estimated by reviewers assuming no censoring | 8 |

| Folkestad, 2016 [13], Denmark | Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) | 1977–2012 | FU to 31 Dec 2013, up to 20 years (for this review) | All patients with OI diagnosis on National Patient Register included, survival up to 20 years for patients born from 1977 included in this review | Survival estimated by reviewers using data on deaths and number at risk provided by authors on request | 9 |

| Frid, 1999 [65], northern Sweden | DS | 1973–1980, FU 1973–1997 | Complete FU to age 14.5 years (n = 213, 95.1%) | All with DS, with or without associated anomalies | Mortality reported, survival estimated by reviewers | 6 |

| Garne, 2002 [51], Funen County, Denmark | Gastrointestinal anomalies (atresias, abdominal wall defects, and CHD) | 1980–1993, FU 1980–98 | FU of all patients to 5 years of age | All patients with and without associated anomalies | Number of deaths and survivors reported, survival estimated by reviewers | 6 |

| Glasson, 2016 [66], WA | DS | 1980–2010, censored to end 2013 | FU to 31 Dec 2013, up to 25 years for birth years 1980–2010 | From the survival analysis, deaths within the first 24 hours excluded (n = 11) | 1-, 5-, 10-, 20-, and 25-year K-M survival estimates with 95% CI reported | 7 |

| Grizelj, 2010 [57], Croatia | BA | 1992–2006 | FU to 31 Dec 2006, (median 2.65 years, range 0.2–14.3) (6.9% [2/29] lost to FU) | 1 inoperable patient excluded from survival analysis | K-M 5- and 10-year native liver survival (NLS) estimates with 95% CI reported; all deaths included by reviewers for the overall survival | 6 |

| Gudbjartsson, 2008 [53], only Iceland centre included | CDH | 1983–2002 | FU 1983 to Apr 2005, 3-year FU of all patients (mean FU 5 years) | Only early presenters (diagnosed within first 24 hours, n = 19) included | 3-year survival reported for early presenters, overall survival estimated by reviewers (n = 23) | 6 |

| Halliday, 2009 [67], Victoria, Australia | DS | 2 birth cohorts: 1988–1990 and 1998–2000 | FU to 2005, 5-year FU for all births (unless the child died interstate; percentage of migration < 2%) | Patients with associated anomalies (n = 121 in 1988–1990 and n = 89 in 1998–2000) included | K-M 5-year survival reported, 1-year survival estimated by reviewers | 6 |

| Hayes, 1997 [68], Dublin, Ireland | DS | 1980–1989 | FU data collected in 1992 (range 3–12 years) (vital status unavailable in 1.3%, n = 5) | Patients with associated anomalies (n = 212) included (data on additional CAs available in 365/389, 93.6%) | K-M survival reported for 1980–1989, and for 1980–1994 and 1985–1989 | 6 |

| Hinton, 2017 [18], Atlanta, USA | CDH | 1979–2003 | FU to death or censored at 31 Dec 2006; 3-year survival complete for all cases | Excluded children with known chromosomal anomalies or syndromes | K-M overall survival reported by various factors, K-M survival curves plotted for White and Black ethnicity by birth period, poverty, and CHD | 6 |

| Jaillard, 2003 [54], France | CDH | 1991–1998 | FU to 2 years of all the surviving infants with CDH | Patients with associated lethal CAs (n = 9) excluded | Early (<2 months) and late deaths (between 2 months and 3 years) reported, 2-year survival with 95% CI estimated by reviewers | 6 |

| Kucik, 2013 [19], 10 regions, USA | DS | 1983–2003 | FU ranged from 9 to 22 years between the regions (8 regions with up to 11+ years, 4 with 20–22 years) | Cases with additional anomalies (e.g., CHD) included | K-M survival estimates with 95% CI reported for 1, 5, 10, and 20 years | 6 |

| Lampela, 2012 [60], Finland | BA | 1987–2010 | FU to 4 full years for all live births with BA | All BA cases included: with BASM (n = 9, 14%), with other anomalies (n = 6, 9%) | Actuarial 4-year survival estimates reported and final figures provided by author on request, 95% CI calculated by reviewers | 6 |

| Leonard, 2000 [69], WA | DS | 1980–1996 | FU to 10 years for all born in 1980–1985, to 10 years for 1986–1990, and to 5 years for 1991–1996 | Cases with additional anomalies (e.g., CHD) included | K-M 1-, 5-, and 10-year survival estimates reported, overall and by 3 birth periods | 6 |

| Leonhardt, 2011 [61], Germany | BA | 2001–2005 | FU to 2 full years (16/183 lost to FU, 8.7%) | All with BA diagnosis included | 2-year K-M survival estimates after Kasai hepatoportoenterostomy (KP) or liver transplantation reported, overall survival (including 3 initial deaths) calculated by reviewers | 5 |

| Lionti, 2012 [73], Victoria, Australia | Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) | 1950 to 31 May 2010 | FU to 35 years of age, loss to FU not reported | Only patients with diagnosed PWS included, infant deaths may have been missed by the register | K-M survival estimates with 95% CI reported for 10, 20, 30, and 35 years, estimates for 1, 5, 15, and 25 years extracted from K-M curves | 5 |

| Löf Granström, 2017 [24], Sweden | Hirschsprung disease (HSCR) | 1964–2013 | FU to 31 Dec 2013 (up to 50 years of age), median 19 years (range 2–49), loss to FU not reported† | Only those with confirmed diagnosis of HSCR included (n = 739), those with HSCR and DS also included | K-M survival curves with 95% CI presented up to 50 years, survival estimates up to 25 years extracted by reviewers | 8 |

| McKiernan, 2000 [39], UK and Ireland | BA | Mar 1993 to end Feb 1995 | FU up to 5 years (median 3.5 years, range 0.3–5.4), lost to FU 2.2% | Those with additional CAs included (n = 20, n = 9 BASM) | Actuarial survival estimated by K-M method and 5-year overall survival and NLS reported | 6 |

| McKiernan, 2009 [38], UK and Ireland | BA | Mar 1993 to end Feb 1995 | FU: median age at last FU 12 years (range 0.25–14), only 2 lost to FU (2.2%) | Those with additional CAs included (n = 20, n = 9 BASM) | Actuarial survival estimated by K-M method and 13-year overall survival and NLS reported | 6 |

| Meyer, 2016 [72], 9 states, USA | Trisomy 13 and trisomy 18 | 1999–2007 | FU 1999–2008, birth years 1999–2005 included for survival estimation to 5 years, loss to FU not reported† | All cytogenetic variants included; different birth years included in different states | K-M survival estimates with 95% CI (<28 days, <1 year, and <5 years) reported | 6 |

| Nelson, 2016 [25], Ontario, Canada | Trisomy 13 and trisomy 18 | 1991–2012 | FU 1991–2013, up to 7,000 days (1.6%, n = 7 lost to FU) | All cytogenetic variants included (90.2% unspecified, 3.5% mosaic, 6.3% translocation) | K-M survival estimates with 95% CI for 1, 5, and 10 years reported | 6 |

| Nembhard, 2010 [43], Texas, USA | All CAs, not stratified by group | 1996–2003 | FU to 2005, 5-year survival analysed; loss to FU not reported† | 3.7% (unduplicated n = 1,877) excluded: trisomy 13 or 18 (n = 511); not born to non-Hispanic White (NHW), non-Hispanic Black (NHB), or Hispanic mother (n = 1,340); deaths with no date of death (n = 50) | 5-year K-M survival estimates with 95% CI for NHW, NHB, and Hispanic ethnicity for term and preterm births reported and by size at birth | 6 |

| Nio, 2003 [62], Japan | BA | 1989–1999 | 1989 only: compete FU for 10-year survival; 1989–1994: complete FU for 5-year survival, 2.6% lost to FU (n = 19) | BA cases with additional anomalies included (19.6% including n = 33 with BASM) | 5- and 10-year survival estimates reported only for those birth years with complete FU | 6 |

| Oddsberg, 2012 [9], Sweden | Oesophageal atresia | 1964–2007 | Complete FU of the nationwide cohort by birth year, up to 25 years for 1964–1969 (percentage missing negligible) | Patients older than 1 year at diagnosis excluded to avoid misclassification; cases with associated CAs included | K-M survival estimates up to 20 years by time period extracted from K-M curves by reviewers | 9 |

| Pakarinen,2018 [58], Nordic countries | BA | 1 Jan 2005 to 30 Jun 2016 | FU for at least 4 months, median 4.9 (IQR 1.8–7.9 years) | Noncurable CHD or central nervous system CA (n = 4) withdrawn from treatment and excluded from the survival analysis, other associated CAs (n = 41, BASM n = 19) included | K-M 5- and 10-year survival estimates reported for 154 included cases, survival estimated by reviewers based on all 158 BA patients for consistency | 6 |

| Rankin, 2012 [14], Northern England | DS | 1985–2003 | FU to 29 Jan 2008, 95.3% traced (669/702) | All live-born patients with DS—full trisomy 21, mosaicism, and translocation—were included | K-M survival estimates with 95% CI reported for 1, 5, 10, and 20 years | 6 |

| Rasmussen, 2006 [70], Metropolitan Atlanta, USA | DS | 1979–1998 | 1979–1999, FU complete for 1979–1988 for 10-year survival, censored by 20 years (loss to FU not reported†) | 47 (of 692) excluded: cytogenetic results unavailable (22), complex rearrangements involving chromosome 21 (7), mosaicism (16), and not DS (2) | K-M survival estimates with 95% CI reported for 1 and 10 years, 5- and 20-year estimates with 95% CI extracted from K-M curves by reviewers | 6 |

| Risby, 2017 [21], southern Denmark | Gastroschisis | 1997–2009 | FU to 5 years for the whole cohort (between Jun 2013 and Apr 2014) | All cases with gastroschisis included | 1- and 5-year survival estimated by reviewers using mortality data | 6 |

| Schneuer, 2019 [42], New South Wales (NSW), Australia | All anomalies, by group and subtype by European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies (EUROCAT) classification | 2004–2009 | FU to death, 5 years of age, or until 31 Mar 2014, whichever came first | Excluded cases without linked birth records (n = 701), mothers residents outside NSW (n = 110), born at 19 weeks of gestation (n = 3) | K-M 1- and 5-year survival estimates with 95% CI reported | 6 |

| Schreiber, 2007 [63], Canada | BA | 1985–2002 | FU up to 10 years, 7% missing survival data for 1985–1995, no missing for 1996–2002 | All with confirmed diagnosis of BA included, including 27 (14%) with BASM phenotype | K-M survival estimates with 95% CI reported for 4 and 10 years | 6 |

| Shin, 2012 [46], 10 regions, USA | Spina bifida: | 1979–2003 | FU to 2004 (up to 20 years for 1983–2003) for 8 registries, loss to FU not reported† | Cases with associated anomalies (e.g., major CHD) included | K-M 1-, 5-, and 20-year survival reported for 1983–2003; other: extracted from K-M curves by reviewers | 6 |

| Siffel, 2003 [47], Atlanta, USA | Encephalocele | 1979–1998 | FU 1979–1999 (for survivors censored at 31 Dec 1999); loss to FU not reported† | Excluded 8 cases: trisomy 13 (1), trisomy 18 (1), amniotic bands (3), coded with ‘possible’ diagnosis (3); with other major CAs included (n = 17) | K-M survival estimates reported for 1, 5, and 20 years—overall and by risk factor | 6 |

| Simmons, 2014 [20], Texas, USA | Achondroplasia | 1996–2005 | FU to 31 Dec 2007 up to age 10 years (minimal 2-year FU for all patients), none lost to FU | All with confirmed diagnosis of achondroplasia included | Mortality reported, 2-year survival with 95% CI estimated by reviewers (no censoring, as all FU to age 2 years) | 6 |

| Sutton, 2008 [44], Dublin, Ireland | Spina bifida, encephalocele | 1976–1987 | Retrospective data collection between Aug 1989 and Apr 1990 for 5-year survival (1.1% [n = 6] lost to FU) | Excluded: those with anencephaly and with spina bifida occulta; infants lost to FU immediately after birth (n = 6) | K-M 1- and 5-year survival estimates (no 95% CI) reported | 6 |

| Tennant, 2010 [15], Northern England | All anomalies, by group and subtype | 1985–2003 | FU to 29 Jan 2008, up to 20 years; 99% traced (10,850/10,964) | Excluded individuals with unavailable data on survival status (114; 1%); those with chromosomal anomalies outside the EUROCAT range (ICD codes Q940-59) | K-M survival estimates with 95% CI reported for EUROCAT CA groups and subtypes for 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 years | 6 |

| Tu, 2015 [59], South Australia | BA | 1989–2000 | The median FU period 13.4 years (IQR, 6.2–18.2; range 0.6–21), no loss to FU | Excluded 2 patients, as the initial KP was performed interstate | K-M 5-year survival estimates with 95% CI reported by authors for both overall survival and NLS | 6 |

| Wang, 2011 [40], New York state, USA | All anomalies and by group | 1983–2006 | FU to end 2008 for up to 25 years (assuming alive if no death by 31 Dec 2008), loss to FU not reported | Only Congenital Malformations Registry cases matched to their birth certificates (97%) included (n = 57,002), cases with additional anomalies included | K-M survival estimates with 95% CI reported for selected CA groups and subtypes for 1, 5, 15, and 25 years | 5 |

| Wang, 2015 [41], 12 states, USA | All anomalies and by group | 1999–2007 | FU to end 2008 (ranging from 1 to 9 years), loss to FU not reported | All live births with a major CA included (n = 98,833); infants with multiple defects were included in each relevant birth defect category | K-M survival estimates with 95% CI reported for selected CA groups and subtypes for <1, <2, and <8 years | 5 |

| Wildhaber, 2008 [64], Switzerland | BA | 1994–2004 | Median FU 58 months (range 5–124); no loss to FU | All patients, including those with associated anomalies, were included: BASM (n = 4), other associated anomalies or disease (n = 6) | K-M 5-year survival estimates (overall and NLS) with SE reported, 95% CI calculated by reviewers | 6 |

| Wong, 2001 [48], Atlanta, USA | Spina bifida | 1979–1994 | FU 1979–1996, loss to FU not reported† | Excluded cases associated with anencephaly or trisomies 13 or 18 | K-M survival estimates with 95% CI to age 18 years (1, 5, 10, 15, 18) | 6 |

*Study data quality was measured using Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies—maximum 9, maximum 6 for those with no comparison group/nonexposed cohort. Scores of <5 indicated high risk of bias [95].

†Loss to FU likely to be low as the linkage system for tracing deaths is well established (involving linkage with the National Death Index in the USA studies for deaths outside the state).

‡Data from Atlanta, USA, are not included, as they are part of the cohort used by Wang and colleagues [41].

As our literature search was restricted to years between January 1995 and April 2020, the publication years ranged between 1997 [68] and 2020 [71], whereas patients were mostly born between 1970 and 2010, with the earliest birth year in 1950 [73] and the latest ending in June 2016 [58]. Table 1 also describes the duration of follow-up, the survival age analysed, and whether survival was reported in the papers (with or without 95% CI) or estimated by our reviewers. Table 1 also gives the NOS scores that range between 5 and 8 respective of the use of the comparison group that is not mandatory for the survival studies (see S3 Table for detailed scoring). According to NOS, all studies were of low risk of bias.

Survival of children with different congenital anomalies

Table 2 shows survival estimates overall and by birth cohort, where reported, for individuals up to 25 years of age for studies estimating survival for all congenital anomalies combined and by different group/type. S5 Table presents more detail for studies reporting survival estimates by other risk factors (e.g., ethnicity or presence of additional anomalies). Most studies reported 1- and 5-year survival estimates only. Survival varied considerably according to anomaly; therefore, survival estimates are presented by different groups and subtypes (Table 2). The 5-year survival for all anomalies combined varied from 85% to 95%, owing to different inclusion and exclusion criteria. It was not considered appropriate to pool survival estimates for all congenital anomalies combined, because of the diversity of the contributing congenital anomaly groups.

Table 2. Survival estimates by congenital anomaly type at age 1–25 years, overall and by birth cohort.

| Congenital anomaly group/subtype | Study and birth year | N deaths/live births | Survival estimates percentage (95% confidence interval [95% CI]) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 5 years | 10 years | 15 years | 20 years | 25 years | |||

| All congenital anomalies | ||||||||

| International Classification of Diseases Revision 9 (ICD-9) codes 740.0–759.9 | Agha, 2006 [6], 1979–1986, Canada | 3620/45,200 | 93.4 | 92.5 | 92.3 | — | — | — |

| ICD-9 codes 740–759 | Berger, 2003 [7], 1992–1998, USA | 2182/43,708 | 95.7 | 95.0 | — | — | — | — |

| British Paediatric Association (BPA)-ICD-9 codes 740–759 | Dastgiri, 2003 [17], 1980–1997, Scotland | 740/6153 | 89.11 | 87.95 | — | — | — | — |

| ICD-8 codes (740–759) | Eide, 2006 [8], 1967–1979, Norway | 1169/9186 | — | — | — | — | 87.4a | — |

| ICD-9 740.00–758.090 | Nembhard, 2010 [43], 1996–2003, USA | 3518/48,391 | 93.7 | 92.7 | — | — | — | — |

| ICD-10 (Q00-Q99) | Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 1465/10,850 | — | — | — | — | 85.5 (84.8–86.3) | — |

| ICD-9 codes 740–759 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 9112/57,002 | 87.1 (86.8–87.4) | 85.2 (84.9–85.5) | — | 83.9 (83.6–84.2) | — | 82.7 (82.4–83.1) |

| Neural tube defects | ||||||||

| Including anencephaly | Dastgiri, 2003 [17], 1980–1997, Scotland | 40/144 | 72.2 (64.9–79.5)b | 71.5 (63.8–79.3)b | — | — | — | — |

| Including anencephaly | Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, New South Wales (NSW), Australia | 34/110 | 69.1 (60.5–77.7) | 69.1 (60.5–77.7) | — | — | — | — |

| Including anencephaly | Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 87/226 | 65.0 (58.4–70.9) | 62.8 (56.2–68.8) | 62.4 (55.7–68.3) | 62.4 (55.7–68.3) | 63.4 (53.4–66.7) | — |

| Excluding anencephaly | Sutton, 2008 [44], 1976–1987, Ireland | 313/543 | 43.7 | 40.8 | — | — | — | — |

| Anencephaly | ||||||||

| ICD-9 code 740.0–740.2 | Agha, 2006 [6], 1979–1986, Canada | 183/ | 4.8 | 4.6 | — | — | — | — |

| Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 19/19 | 0.0 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 17/17 | 0.0 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| ICD-9 740.0–740.1 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 447/479 | 7.3 (5.2–9.9) | 6.8 (4.8–9.3) | — | 6.5 (4.5–9.0) | — | 6.5 (4.5–9.0) |

| Spina bifida | ||||||||

| ICD-9 code 741.0–741.9 | Agha, 2006 [6], 1979–86, Canada | 182/ | 78.5 | 75.3 | — | — | — | — |

| ICD-10 Q05 and ICD-9 741 | Bakker, 2019 [49], 2001–2012, Czech Republic | /139 | 91.4 | 90.0 | 88.6c | — | — | — |

| Malta Congenital Anomaly Registry | /28 | 92.8 | 92.8 | — | — | — | — | |

| Sweden | /263 | 92.5 | 92.1 | 91.7c | — | — | — | |

| UK–Wales | /78 | 91.0 | 89.7 | 89.7c | — | — | — | |

| USA–Arkansas | /177 | 87.0 | 84.2 | 83.1c | — | — | — | |

| USA–Texas | /1,578 | 91.6 | 90.5 | 90.1c | — | — | — | |

| USA–Utah | /213 | 90.7 | 90.7 | 90.2c | — | — | — | |

| USA–Atlanta, 2001–2008 | /112 | 95.5 | 95.5 | 95.5c | — | — | — | |

| Italy–Lombardy, 2003–2012 | /25 | 100.0 | 96.0 | — | — | — | — | |

| Myelomeningocele | Borgstedt-Bakke, 2017 [45], 1970–1979, Denmark | 16/58 | 84.5 | 84.5 | 82.8 | 79.4 | 79.4 | — |

| 1980–1989 | 5/39 | 97.5 | 92.4 | 92.4 | 92.4 | 89.8 | — | |

| 1990–2015 | 6/90 | 95.6 | 95.6 | 94.5 | 92.8 | 92.8 | — | |

| Spina bifida (ICD-8 code 741) | Eide, 2006 [8], 1967–79, Norway | 56/113 | — | — | — | — | 50.4a | — |

| Spina bifida | Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 11/56 | 80.4 (70.0–90.8) | 80.4 (70.0–90.8) | — | — | — | — |

| ICD-9 741.0 and 741.9 | Shin, 2012 [46], 1997–2003, USA | 162/2,259 | 92.8 (91.7–93.8) | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1983–1987 | 87.1 | 84.5 | 82.7 | 80.7 | 80.4 | — | ||

| 1988–1992 | 90.4 | 87.6 | 86.7 | 85.7 | — | — | ||

| 1993–1997 | 89.9 | 88.2 | 87.2 | — | — | — | ||

| 1998–2003 | 92.8 | 90.8 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Myelomeningocele and spinal meningocele | Sutton, 2008 [44], Ireland | /373 | 50.4 | 47.3 | — | — | — | — |

| Spina bifida, ICD-10 Q05 | Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 63/195 | 70.8 (63.8–76.6) | 69.2 (62.2–75.2) | 68.7 (61.6–74.7) | 68.7 (61.6–74.7) | 66.4 (58.9–72.9) | — |

| ICD-9 741.0, 741.9 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 324/1999 | 88.5 (87.0–89.8) | 86.4 (84.8–87.8) | — | 83.8 (82.0–85.4) | — | 82.2 (80.1–84.0) |

| Spina bifida without anencephaly | Wang, 2015 [41], 1999–2007, USA | 318/3903 | 91.9 (90.9–92.7) | — | 90.2 (89.0–91.2)d | — | — | — |

| Wong, 2001 [48], USA, 1979–1994 | 45/235 | 87.2 (83.1–91.6) | 83.8 (79.2–88.6) | 80.9 (75.8–86.3) | 78.4 (72.4–84.7) | 78.4 (72.4–84.7)a | — | |

| 1979–1983 | 83 (75–91) | 82 (73–90) | 79 (71–88) | — | 76 (68–86)a | — | ||

| 1984–1988 | 89 (92–96) | 85 (78–93) | 81 (73–90) | — | — | — | ||

| 1989–1994 | 91 (85–98) | 84 (75–94) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Encephalocele | ||||||||

| Siffel, 2003 [47], 1979–1998, USA | 25/83 | 72.2 (62.6–81.9) | 70.8 (60.9–80.7) | — | — | 67.3 (55.7–78.8) | — | |

| Sutton, 2008 [44], 1976–1987, Ireland | /64 | 32.9 | 27.3 | |||||

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 7/14 | 64.3 (34.3–83.3) | 50.0 (22.9–72.2) | 50 (22.9–72.2) | 50 (22.9–72.2) | — | — | |

| ICD-9 742.0 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 171/556 | 75.7 (71.9–79.1) | 72.1 (68.1–75.6) | — | 69.7 (65.6–73.4) | — | 67.2 (62.7–71.3) |

| Wang, 2015 [41], 1999–2007, USA | 254/909 | 72.1 (69.0–74.9) | — | 69.9 (66.1–73.3)d | — | — | — | |

| Hydrocephalus | ||||||||

| Eide, 2006 [8], 1967–1979, Norway | 29/59 | — | — | — | — | 50.8a | — | |

| Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 15/60 | 75.0 (64.0–86.0) | 75.0 (64.0–86.0) | — | — | — | — | |

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 32/108 | 76.9 (67.8–83.7) | 75.0 (65.7–82.1) | 71.2 (61.3–79.0) | 69.8 (59.6–77.8) | 66.4 (54.5–75.9) | — | |

| 742.3 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 1,314/5,378 | 82.7 (81.6–83.7) | 78.5 (77.4–79.6) | — | 75.3 (74.1–76.5) | — | 73.4 (72.1–74.7) |

| Orofacial clefts | ||||||||

| Cleft palate and cleft lip (749.0–749.9) | Agha, 2006 [6], 1979–1986, Canada | 188/ | 90.2 | 88.2 | — | — | — | — |

| Orofacial clefts (749.0–749.9) | Bell, 2016 [16], 1980–2010, Western Australia | 113/1,509 | 92.5 (91.0–93.8) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Orofacial clefts | 1980–1992 | 73/585 | — | 87.5 (84.5–90.0) | — | — | — | — |

| Cleft lip only (BPA-ICD-9–749.10–749.19) | 1980–2010 for 1 year, 1980–2007 for 5 years; 1980–1992 for 20 years | 95.8 (all) 99.7 (isolated) |

95.8 (all) 99.7 (isolated) |

— | — | 97.7 (all) 100.0 (isolated) |

— | |

| Cleft lip and palate (749.20–749.27, 749.29) | 1980–2010 for 1 year, 1980–2007 for 5 years, 1980–1992 for 20 years | 91.2 (all) 99.1 (isolated) |

99.1 (isolated) | — | — | 84.5 (all); 98.0 (isolated) |

— | |

| Cleft palate (749.00–749.09) | 1980–2010 for 1 year, 1980–1992 for 20 years | 91.7 (all) 99.2 (isolated) |

— | — | — | 83.5 (all); 97.2 (isolated) |

— | |

| Cleft lip with/without palate | Dastgiri, 2003 [17], 1980–1997, Scotland | 5/278 | 98.2 (96.8–99.6)b | 98.2 (96.6–99.8)b | — | — | — | — |

| Cleft lip | Eide, 2006 [8], 1967–1979, Norway | 6/250 | — | — | — | — | 97.6a | — |

| Cleft palate | 9/151 | — | — | — | — | 94.0a | — | |

| Cleft lip and palate | 19/357 | — | — | — | — | 94.7a | — | |

| Orofacial clefts | Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 7/575 | 99.0 (98.1–99.8) | 98.8 (97.9–99.7) | — | — | — | — |

| Cleft lip and palate | 0/188 | 100.0 | 100.0 | — | — | — | — | |

| Orofacial clefts | Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 14/584 | 97.8 (96.2–98.7) | 97.8 (96.2–98.7) | 97.6 (95.9–98.6) | 97.6 (95.9–98.6) | 97.6 (95.9–98.6) | — |

| Cleft lip | 1/140 | 99.3 (95.0–99.9) | 99.3 (95.0–99.9) | 99.3 (95.0–99.9) | 99.3 (95.0–99.9) | 99.3 (95.0–99.9) | — | |

| Cleft lip and palate | 5/227 | 98.2 (95.4–99.3) | 98.2 (95.4–99.3) | 97.7 (94.6–99.1) | 97.7 (94.6–99.1) | 97.7 (94.6–99.1) | — | |

| Cleft palate | 8/217 | 96.3 (92.8–98.1) | 96.3 (92.8–98.1) | 96.3 (92.8–98.1) | 96.3 (92.8–98.1) | 96.3 (92.8–98.1) | — | |

| Cleft lip with or without cleft palate | 6/367 | 98.6 (96.8–99.4) | 98.6 (96.8–99.4) | 98.3 (96.3–99.2) | 98.3 (96.3–99.2) | 98.3 (96.3–99.2) | — | |

| Cleft palate without cleft lip (ICD-9 749.0) | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 410/3,719 | 91.0 (90.0–91.8) | 89.6 (88.6–90.6) | — | 88.9 (87.8–89.9) | — | 88.3 (87.1–89.4) |

| Cleft lip with/without cleft palate (ICD-9 749.1–749.2) | 454/4,691 | 91.7 (90.9–92.5) | 90.8 (89.9–91.6) | — | 90.2 (89.3–91.0) | — | 90.0 (89.1–90.8) | |

| Cleft palate without cleft lip | Wang, 2015 [41], 1999–2007, USA | 660/7,356 | 91.0 (90.4–91.7) | — | 90.3 (89.5–91.1)d | — | — | — |

| Cleft lip with or without cleft palate | 999/11,862 | 91.6 (91.1–92.1) | — | 90.8 (90.1–91.4)d | — | — | — | |

| Digestive system anomalies | ||||||||

| Oesophageal atresia | ||||||||

| ICD-9 code 750.3 | Cassina, 2016 [50], 1981–2012 (all), Northeast Italy | /330 | 88.4 (84.9–91.9) | — | — | — | — | 85.1 (80.8–89.4) |

| 1981–1996 (isolated) | 96.1 | 94.6 | 94.6 | 90.6 | 90.6 | 90.6 | ||

| 1997–2012 (isolated) | 95.3 | 95.3 | 95.3 | 95.3 | — | — | ||

| 1981–1996 (non-isolated) | 63.0 (49.1–76.9)e | 58.7 (44.4–73.0) | 58.7 (44.4–73.0)e | 58.7 (44.4–73.0) | 58.7 (44.4–73.0) | 58.7 (44.4–73.0) | ||

| 1997–2012 (non-isolated) | 88.4 (82.7–94.1)e | 87.3 (81.2–93.4) | 87.3 (81.2–93.4)e | 87.3 (81.2–93.4) | — | — | ||

| Garne, 2002 [51], Denmark | 11/27 | — | 59.3 (39.0–77.0) | — | — | — | — | |

| ICD-7 756.21, ICD-8 750.20, 750.28, ICD-9 750D, ICD-10 Q39.0–Q39.2. | Oddsberg, 2012 [9], 1964–2007, Sweden | 227/1,126 | 82.1 | 80.7 | 80.6 | 80.5 | 80.1 | |

| 1964–1969 | 62.1 | 62.1 | 62.1 | 62.1 | 58.5 | 58.5 | ||

| 1970–1979 | 77.2 | 75.6 | 75.6 | 75.2 | 75.2 | 75.2 | ||

| 1980–1989 | 82.5 | 82.1 | 81.9 | 81.9 | 80.5 | — | ||

| 1990–1999 | 86.1 | 85.1 | 85.1 | 84.9 | — | — | ||

| 2000–2007 | 87.8 | 87.6 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 0/51 | 100.0 | 100.0 | — | — | — | — | |

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, northern England | 7/105 | 95.2 (88.9–98.0) | 93.3 (86.5–96.8) | 93.3 (86.5–96.8) | 93.3 (86.5–96.8) | 93.3 (86.5–96.8) | — | |

| ICD-9 750.3 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 336/1,580 | 81.5 (79.5–83.4) | 79.5 (77.4–81.4) | — | 78.6 (76.4–80.5) | — | 78.3 (76.1–80.3) |

| Wang, 2015 [41], 1999–2007, USA | 476/3,084 | 84.6 (83.2–85.8) | — | 83.8 (82.1–85.2)d | — | — | — | |

| Anorectal malformations | ||||||||

| ICD-9/BPA 752.1–752.4, cloaca—751.55 | Cassina, 2019 [52], Northeast Italy, 1990–2012 | /253 | 89.7 (85.2–92.9) | — | — | — | 86.7 (81.6–90.4) | — |

| Anorectal atresia or stenosis | ||||||||

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 2/83 | 98.8 (91.8–99.8) | 98.8 (91.8–99.8) | 98.8 (91.8–99.8) | 96.6 (86.1–99.2) | 96.6 (86.1–99.2) | — | |

| ICD-9 751.2 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 374/2,654 | 87.7 (86.4–88.9) | 86.5 (85.2–87.8) | — | 85.9 (84.5–87.2) | — | 84.8 (83.1–86.4) |

| Wang, 2015 [41], 1999–2007, USA | 702/5,400 | 87.0 (86.1–87.9) | — | 86.1 (85.0–87.2)d | — | — | — | |

| Hirschsprung disease | ||||||||

| ICD-7: 756.31, ICD-8: 751.39, ICD-9: 751D, ICD-10: Q431 | Löf Granström, 2017 [24], 1964–2013, Sweden | 22/739 | 99.3 (98.7–99.8) | 98.3 (97.4–99.2) | 98.3 (97.4–99.2) | 97.9 (96.9–99.0) | 97.7 (96.5–98.8) | 97.7 (96.5–98.8) |

| Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 5/90 | 96.7 (93.0–100) | 94.4 (89.7–99.2) | — | — | — | — | |

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 4/61 | 93.4 (83.5–97.5) | 93.4 (83.5–97.5) | 93.4 (83.5–97.5) | 93.4 (83.5–97.5) | 93.4 (83.5–97.5) | — | |

| Biliary atresia | ||||||||

| Overall survival | ||||||||

| Chardot, 2013 [36], 1986–2009, France | 228/1,107 | — | 80.8 (78.4–83.2) | 79.7 (77.2–82.2) | 78.6 (75.9–81.3) | 77.6 (74.5–80.7) | — | |

| 1986–1996 | — | 72.1 (68.0–76.2) | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1997–2002 | — | 88.0 (84.1–91.9) | — | — | — | — | ||

| 2003–2009 | — | 88.5 (84.8–92.2) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Davenport, 2011 [37], 1999–2009, England and Wales | 41/443 | — | 90 (88–93) | 89 (86–93) | — | — | — | |

| De Carvalho, 2010 [55], 1982–2008, Brazil | 166/513 | — | 67.6f | — | — | — | — | |

| De Vries, 2011 [56], the Netherlands | ||||||||

| 1977–1982 | 32/49 | — | — | — | — | 34.7 (22.1–49.7) | ||

| 1983–1988 | 27/55 | — | — | — | — | 50.9 (37.2–64.5) | ||

| Grizelj, 2010 [57], 1992–2006, Croatia | 7/29 | — | 75.9 (56.1–89.0) | 75.9 (56.1–89.0) | — | — | — | |

| Lampela, 2012 [60], 1987–2010, Finland | 27/72 | — | 62.5 (50.3–73.4)h | — | — | — | — | |

| Leonhardt, 2011 [61], 2001–2005, Germany | 31/183 | 81.9 (75.4–87.0)k | — | — | — | — | — | |

| McKiernan, 2000 [39], 1993–1995, UK and Ireland | 14/93 | — | 85.0 (77.7–92.3) | — | — | — | — | |

| McKiernan, 2009 [38], UK and Ireland | 15/93 | — | — | 83.8 (76.2–91.4)l | — | — | — | |

| Nio, 2003 [62], Japan | ||||||||

| 1989 birth year | 35/108 | — | — | 66.7 | — | — | — | |

| 1989–1994 | 182/735 | — | 75.3 | — | — | — | — | |

| Pakarinen, 2018 [58], 2005–2016, Nordic countries | 21/158 | — | 87.3 (80.9–91.9) | 86.7 (80.2–91.4) | — | — | — | |

| Schreiber, 2007 [63], Canada | ||||||||

| 1985–2002 | 81/349 | 77 (72–92)h | 75 (70–80) | — | — | — | ||

| 1985–1995 | 55/199 | 74 (67–79)h | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1996–2002 | 26/150 | 82 (75–88)h | — | — | — | — | ||

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 3/14 | 85.7 (53.9–96.2) | 85.7 (53.9–96.2) | — | — | — | — | |

| Tu, 2015 [59], 1989–2000, South Australia | 13/29 | — | 89.7 (71.5–97.3) | — | — | — | — | |

| Wildhaber, 2008 [64], 1994–2004, Switzerland | 4/48 | 91.5 (83.5–99.5)k | 91.5 (83.5–99.5) | 91.5 (83.5–99.5) | — | — | — | |

| Biliary atresia | ||||||||

| Survival with native liver (NLS) | ||||||||

| Chardot, 2013 [36], 1986–2009, France | (99 + 542)g/1,035 | — | 40.0 (36.9–43.1) | 35.8 (32.7–38.9) | 32.1 (28.8–35.4) | 29.6 (25.7–33.5) | — | |

| 1986–1996 | — | 38.2 (32.9–43.5) | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1997–2002 | — | 43.1 (37.0–49.2) | — | — | — | — | ||

| 2003–2009 | — | 39.0 (32.5–45.5) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Davenport, 2011 [37], 1999–2009, England and Wales | (24 + 179)g/424 | — | 46 (41–51) | 40 (34–46) | — | — | — | |

| De Carvalho, 2010 [55], 1982–2008, Brazil | (94 + 165)g/392 | — | 36.8h | — | — | — | — | |

| De Vries, 2011 [56], the Netherlands | ||||||||

| 1977–1982 | (31 + 8)g/49 | — | — | — | — | 20.4 (10.7–34.8)g | — | |

| 1983–1988 | (21 + 16)g/55 | — | — | — | — | 32.7 (21.0–46.8)g | — | |

| Grizelj, 2010 [57], 1992–2006, Croatia | (6 + 6)/28 | — | 51.7 (40.6–62.8) | 38.8 (24.9–52.7) | — | — | — | |

| Lampela, 2012 [60], 1987–2010, Finland | (19 + 25)/72 | — | 38.9 (27.8–51.1)h | — | — | — | — | |

| Leonhardt, 2011 [61], 2001–2005, Germany | (28 + 105)/167 | 20.4 (14.7–27.4)k | — | — | — | — | — | |

| McKiernan, 2000 [39], 1993–95, UK and Ireland | (14 + 33)/93 | — | 49.5 (39.0–60.0) | — | — | — | — | |

| McKiernan, 2009 [38], UK and Ireland | (10 + 42)/93 | — | — | 43.8 (33.3–54.1)l | — | — | — | |

| Nio, 2003 [62], Japan | ||||||||

| 1989 birth year | 51/108 | — | — | 52.8 | — | — | — | |

| 1989–1994 | /735 | — | 59.7 | — | — | — | — | |

| Pakarinen, 2018 [58], 2005–2016, Nordic countries | 72/154 | — | 53 (45–62) | 45 (35–55) | — | — | — | |

| Schreiber, 2007 [63], Canada | (81 + 169)/349 | 33 (28–38)h | 24 (19–29) | — | — | — | ||

| 1985–1995 | (55 + 98)/199 | 31 (31–38)h | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1996–2002 | (26 + 71)/150 | 36 (28–45)h | — | — | — | — | ||

| Tu, 2015 [59], 1989–2000, South Australia | — | 55.2 (36.0–73.0) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Wildhaber, 2008 [64], 1994–2004, Switzerland | (4 + 27)/48 | 40.5 (26.0–55.0)k | 32.7 (18.6–46.8) | — | — | — | — | |

| CDHo | ||||||||

| ICD-9 756.6, ICD-10 Q79.0 and Q79.1 | Burgos, 2017 [23], 1987–2013 (all fatalities) | 314/861 | 65.4 (62.1–68.5) | 63.5 (60.2–66.7)m | — | — | — | — |

| 1987–1999 (all fatalities) | 210/480 | 56.3 (51.7–60.7)m | — | — | — | — | ||

| 2000–2013 (all fatalities) | 104/381 | 72.7 (67.9–77.1)m | — | — | — | — | ||

| Garne, 2002 [51], 1980–1993 | 10/17 | — | 41.2 (19.4–66.5) | — | — | — | — | |

| Gudbjartsson, 2008 [53], 1983–2002, Iceland | 8/23 | — | 65.2 (42.8–82.8)j | — | — | — | — | |

| BPA code 756.610 | Hinton, 2017 [18], 1979–2003, USA | |||||||

| Overall survival (up to 20 years, minimum of 3 years for all cases) | ||||||||

| <1988 | 22/37 | — | — | 40.5 (23.4–57.6) | — | 40.5 (23.4–57.6) | — | |

| ≥1988 | 41/113 | — | — | 58.3 (46.0–70.6) | — | — | — | |

| Jaillard, 2003 [54], 1991–1998, France | 34/85 | 60.0 (48.9–70.3)j | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 24/90 | 73.3 (64.2–82.5) | 73.3 (64.2–82.5) | — | — | — | — | |

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 69/161 | 58.4 (50.4–65.6) | 57.1 (49.1–64.4) | 57.1 (49.1–64.4) | 57.1 (49.1–64.4) | 57.1 (49.1–64.4) | — | |

| ICD-9 756.6 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 586/1,541 | 63.5 (61.0–65.8) | 62.6 (60.1–64.9) | — | 62.1 (59.6–64.5) | — | 61.4 (58.8–63.8) |

| Wang, 2015 [41], 1999–2007, USA | 1,017/3,248 | 68.7 (67.1–70.3) | — | 68.0 (66.0–69.9)d | — | — | — | |

| Limb anomalies | ||||||||

| Limb reduction defects | ||||||||

| Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 5/52 | 90.4 (82.4–98.4) | 90.4 (82.4–98.4) | — | — | — | — | |

| Upper-limb reduction | ||||||||

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 1/111 | 100.0 | 99.1 (93.8–99.9) | 99.1 (93.8–99.9) | 99.1 (93.8–99.9) | 99.1 (93.8–99.9) | — | |

| ICD-9 755.2 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 199/1,752 | 90.7 (89.2–92.0) | 89.4 (87.9–90.8) | — | 89.0 (87.4–90.4) | — | 87.7 (85.8–89.4) |

| Wang, 2015 [41], 1999–2007, USA | 387/3,602 | 89.3 (88.2–90.2) | — | 88.2 (86.9–89.4)d | — | — | — | |

| Lower-limb reduction | ||||||||

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 3/42 | 92.9 (79.5–97.6) | 92.9 (79.5–97.6) | 92.9 (79.5–97.6) | 92.9 (79.5–97.6) | 92.9 (79.5–97.6) | — | |

| ICD-9 755.3 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 136/1,044 | 88.6 (86.5–90.4) | 87.3 (85.2–89.2) | — | 87.1 (84.9–89.0) | — | 86.7 (84.4–88.6) |

| Wang, 2015 [41], 1999–2007, USA | 219/1,913 | 88.6 (87.0–89.9) | — | 88.2 (86.4–89.8)d | — | — | — | |

| Abdominal wall defects | ||||||||

| Abdominal wall defects | Eide, 2006 [8], 1967–1979, Norway | 72/206 | — | — | — | — | 65.0a | — |

| Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 14/139 | 90.6 (85.8–95.5) | 89.9 (84.9–94.9) | — | — | — | — | |

| Gastroschisis | ||||||||

| Surgical code DQ79.3, JAG10 | Risby, 2017 [21], 1997–2009, South Denmark | 7/71 | 93.0 (83.7–97.4) | 91.5 (81.9–96.5) | — | — | — | — |

| Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 9/109 | 91.7 (86.6–96.9) | 91.7 (86.6–96.9) | — | — | — | — | |

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 12/190 | 93.7 (89.2–96.4) | 93.7 (89.2–96.4) | 93.7 (89.2–96.4) | 93.7 (89.2–96.4) | 93.7 (89.2–96.4) | — | |

| ICD-9 756.73 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 116/777 | 87.8 (85.3–89.9) | 85.5 (82.8–87.8) | — | 84.8 (82.0–87.2) | — | 81.7 (74.0–87.3) |

| Wang, 2015 [41], 1999–2007, USA | 266/3,698 | 92.8 (91.9–93.6) | — | 92.1 (91.0–93.2)d | — | — | — | |

| Omphalocele | ||||||||

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 6/47 | 87.2 (73.8–94.1) | 87.2 (73.8–94.1) | 87.2 (73.8–94.1) | 87.2 (73.8–94.1) | 87.2 (73.8–94.1) | — | |

| ICD-9 756.72 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 200/639 | 69.5 (65.8–72.9) | 68.8 (65.1–72.3) | — | 68.6 (64.9–72.1) | — | 68.6 (64.9–72.1) |

| Wang, 2015 [41], 1999–2007, USA | 367/1,281 | 71.4 (68.8–73.7) | — | 71.2 (68.0–74.1)d | — | — | — | |

| Urinary-system anomalies | ||||||||

| ICD-9 753.0–753.9 | Agha, 2006 [6], 1979–1986, Canada | 451/ | 68.8 | 67.2 | — | — | — | — |

| Dastgiri, 2003 [17], 1980–1997, Scotland | 69/618 | 89.0 | 88.8 | — | — | — | — | |

| Bilateral renal agenesis | Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 5/5 | 0.0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Cystic kidney disease | 9/83 | 89.2 (82.5–95.8) | 89.2 (82.5–95.8) | — | — | — | — | |

| ICD-10 Q60-Q64 | Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 84/1,258 | 93.9 (92.4–95.1) | 93.5 (86.6–94.2) | 93.4 (91.9–94.6) | 93.2 (91.6–94.5) | 93.2 (91.6–94.5) | — |

| Bilateral renal agenesis | 21/21 | 0.0 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Cystic kidney disease | 20/225 | 92.0 (87.6–94.9) | 91.1 (86.6–94.2) | 91.1 (86.6–94.2) | 91.1 (86.6–94.2) | 91.1 (86.6–94.2) | — | |

| Renal agenesis or dysgenesis—ICD-9 753.0 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 693/1,946 | 66.1 (63.9–68.1) | 64.8 (62.6–66.9) | — | 64.2 (62.0–66.3) | — | 63.8 (61.6–66.0) |

| Down syndrome | ||||||||

| 759.3 (ICD-8), 758.0 (ICD-9) and Q90.0, Q90.1, Q90.2 or Q90.9 (ICD-10) | Brodwall, 2018 [22], 1994–2009, Norway | 78/1,251 | 96.3 | 94.2 | — | — | — | — |

| 1994–1999 | 94.2b | 91.8e | — | — | — | — | ||

| 2000–2009 | 97.5b | 95.8e | — | — | — | — | ||

| 758.0 (ICD-9) | Chua, 2020 [71], 1995–2014, Hong Kong | 83/1,010 | 94.4 (92.7–95.7) | 91.8b (89.9–93.4) | — | — | — | — |

| Dastgiri, 2003 [17], 1980–1997, Scotland | 33/210 | 87.1 (82.6–91.7)b | 84.3 (78.3–90.3)b | — | — | — | — | |

| Frid, 1999 [65], 1973–1980, Sweden | 54/213 | 85.4 (79.8–89.8) | 77.4 | 76.5 (70.1–81.9) | 74.6 (68.2–80.2)i | |||

| Glasson, 2016 [66], 1953–2010, Western Australia | 245/1,378 | — | 88 (86–90) | 87 (85–89) | — | — | 83 (80–85) at 30 years | |

| 1980–2010 | 78/772 | |||||||

| 1980–1990 | 93 (89–96) | 86 (81–89) | 85 (80–89) | 84 (79–88) | 82 (77–87) | |||

| 1991–2000 | 97 (94–99) | 96 (92–98) | 95 (91–97) | 94 (90–96) | 94 (90–96) | |||

| 2001–2010 | 96 (92–98) | 94 (90–96) | 94 (90–96) | 94 (90–96) | 94 (90–96) | 94 (90–96) | ||

| Halliday, 2009 [67], Australia | ||||||||

| 1988–1990 | 25/236 | 94.1 | 89.4 | — | — | — | — | |

| 1998–2000 | 10/165 | 94.5 | 93.9 | — | — | — | — | |

| Hayes, 1997 [68], 1980–1989, Ireland | 63/389 | 88.2 (85–91) | 83 (79–87) | 83 (79–87) | — | — | — | |

| 1980–1984 | 87 | 82 | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1985–1989 | 90 | 86 | — | — | — | — | ||

| BPA codes, or both BPA and ICD-9-CM, or ICD9-CM only (North Carolina and Colorado) | Kucik, 2013 [19], 1983–2003 (20-year survival), USA | 1,584/16,506 | 92.9 (92.5–93.2) | 91.0 (90.5–91.4) | 90.7 (90.2–91.1) | — | 88.1 (87.0–89.0) | — |

| 1983–1989 (20-year survival) | 334/2,454 | 91.3 (90.0–92.4) | 88.1 (86.8–89.3) | 87.4 (86.0–88.6) | — | 85.7 (84.1–87.1) | — | |

| 1990–1996 (10-year survival) | 624/5,441 | 91.2 (90.5–92.0) | 89.2 (88.3–90.0) | 88.4 (87.6–89.3) | — | — | — | |

| 1997–2003 (5-year survival) | 608/8,611 | 94.3 (93.8–94.8) | 92.5 (91.9–93.0) | — | — | — | — | |

| Leonard, 2000 [69], 1980–1996, Western Australia | /440 | 91.7 (88.7–94.0) | 87.0 (83.0–89.0) | 85.0 (81.0–89.0) | — | — | — | |

| 1980–1985 | 89 | 80 (72–86)e | 79 | — | — | — | ||

| 1986–1990 | 92 | 86 (79–91)e | 85 | — | — | — | ||

| 1991–1996 | 94 | 93 (88–96)e | — | — | — | — | ||

| Q900–Q902 | Rankin, 2012 [14], Northern England, 1985–1990 | 54/235 | 86.0 (80.8–89.8) | 79.2 (73.4–83.8) | 78.3 (72.5–83.0) | — | 77.5 (71.6–82.3) | — |

| 1991–1996 | 36/193 | 83.9 (78.0–88.4) | 82.4 (76.2–87.1) | 81.9 (75.7–86.6) | — | 80.6 | — | |

| 1997–2003 | 21/241 | 94.2 (90.4–96.5) | 91.7 (87.4–94.6) | 91.2 (86.8–94.2) | — | 90.7 | — | |

| ICD-9-CM (758.000–758.090) | Rasmussen, 2006 [70], 1979–1998, USA | 70/645 | 92.9 (90.9–94.9) | 89.9 (87.3–92.1) | 88.6 (85.0–92.2) | — | 87.4 (84.3–90.5) | — |

| Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 30/425 | 94.1 (91.9–96.4) | 92.9 (90.5–95.4) | — | — | — | — | |

| ICD-9 758.0 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 754/6,819 | 92.0 (91.3–92.6) | 89.9 (89.1–90.6) | — | 88.9 (88.1–89.7) | — | 87.5 (86.5–88.5) |

| Wang, 2015 [41], 1999–2007, USA | 944/15,939 | 94.1 (93.7–94.4) | — | 92.8 (92.3–93.2)d | — | — | — | |

| Trisomy 13 | ||||||||

| Meyer, 2016 [72], 1999–2007, USA | 625/693 | 11.5 (9.3–14.1) | 9.7 (7.2–12.5) | — | — | — | — | |

| ICD-9, 758.1 or ICD-10, Q91.4–Q91.7 | Nelson, 2016 [25], 1991–2012, Canada | /174 | 19.8 (14.2–26.1) | 15 (10–21) | 12.9 (8.4–18.5) | — | — | — |

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 26/29 | 13.8 (4.4–28.6) | — o | — | — | — | — | |

| ICD-9 758.1 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 437/525 | 21.3 (17.9–24.9) | 18.4 (15.3–21.9) | — | 16.2 (13.0–19.7) | 15.2 (12.0–18.8) | |

| Trisomy 18 | ||||||||

| Meyer, 2016 [72], 1999–2007, USA | 984/1,113 | 13.4 (11.5–15.5) | 12.3 (10.1–14.8) | — | — | — | — | |

| ICD-9, 758.2 or ICD-10, Q91.0-Q91.3 | Nelson, 2016 [25], 1991–2012, Canada | /254 | 12.6 (8.9–17.1) | 11 (8–16) | 9.8 (6.4–14.0) | |||

| Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 28/34 | 20.6 (7.0–34.2) | 17.6 (4.8–30.5) | — | — | — | — | |

| Tennant, 2010 [15], 1985–2003, Northern England | 62/63 | 1.6 (0.1–7.5) | — o | — | — | — | — | |

| ICD-9 758.2 | Wang, 2011 [40], 1983–2006, USA | 667/773 | 18.8 (16.1–21.6) | 15.2 (12.8–17.8) | — | 13.2 (10.9–15.8) | — | 12.3 (9.8–15.1) |

| Skeletal dysplasia | ||||||||

| Osteogenesis imperfecta ICD-10 Q78.0 | Folkestad, 2016 [13], 1977–2012, Denmark | 24/366 (up to 20 years) | 94.8 (91.8–96.8) | 94.8 (91.8–96.8) | — | — | 91.6 (88.2–94.2) | — |

| Skeletal dysplasia | Schneuer, 2019 [42], 2004–2009, NSW, Australia | 15/75 | 80.0 (70.9–89.1) | 80.0 (70.9–89.1) | — | — | — | — |

| Achondroplasia BPA code 756.430 | Simmons, 2014 [20], 1996–2005, USA | 4/106 | 96.2 (90.1–98.8) | 96.2 (90.1–98.8)k | — | — | — | — |

| Achondroplasia/Hypochondroplasia | Tennant, 2010 [15], 1983–2003, Northern England | 2/22 | 95.5 (71.9–99.4) | 90.9 (68.3–97.7) | 90.9 (68.3–97.7) | 90.9 (68.3–97.7) | — | — |

| Prader-Willi syndrome | ||||||||

| Lionti, 2012 [73], 1950–2010, Australia | 15/163 (to 35 years) | 98.6 (95.2–99.7) | 98.6 (95.2–99.7) | 97 (93–99) | 96.3 (91.1–98.4) | 94 (88–97) | 89.4 (80.8–94.5) | |

| ICD-10 Q87.1 | Tennant, 2010 [15], 1983–2003, Northern England | 1/10 | 100.0 | 90.0 (47.3–98.5) | 90.0 (47.3–98.5) | — | — | — |

Congenital anomaly subtypes were presented within the major congenital anomaly groups according to the European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies (EUROCAT) classification [26].

Estimates (or 95% CI) in italics were not reported in the article but were estimated from the raw data provided and in italics, and bold values were extracted from Kaplan-Meier or actuarial survival curves. For calculation of 95% CIs, we used the efficient-score method (corrected for continuity) described by Newcombe, 1998 [29], based on the procedure outlined by Wilson, 1927 [30].

a18-year survival values.

bProvided by authors on request or confirmed by authors.

cSurvival at ≥5 years reported.

d8-year survival values.

ep-Values < 0.05.

fOverall survival reported, including all deaths (also without operation or liver transplantation), without specifying age at survival.

gDeaths and secondary liver transplantation used in calculation of NLS.

h4-year survival values.

i14.5-year survival values.

j3-year survival values.

k2-year survival values.

l13-year survival values.

mOverall survival (beyond 1 year of age) for all live births reported.

nThis article (Rankin, 2012 [14]) was included despite being a subset of the larger study analysing all types of congenital anomalies (Tennant and colleagues [15]) because it reported survival by year period and explored predictors of survival. To avoid duplication in reporting, survival for Down syndrome from Tennant and colleagues [15] was included in neither the tables of this review nor the meta-analysis.

oSurvival not reported as <5 cases at risk at the end of the time period.

Congenital anomalies of the nervous system

Survival in live births with anencephaly analysed by four studies was extremely low and varied from 0% [15,42] to 7.3% [40] by year 1 (Table 2).

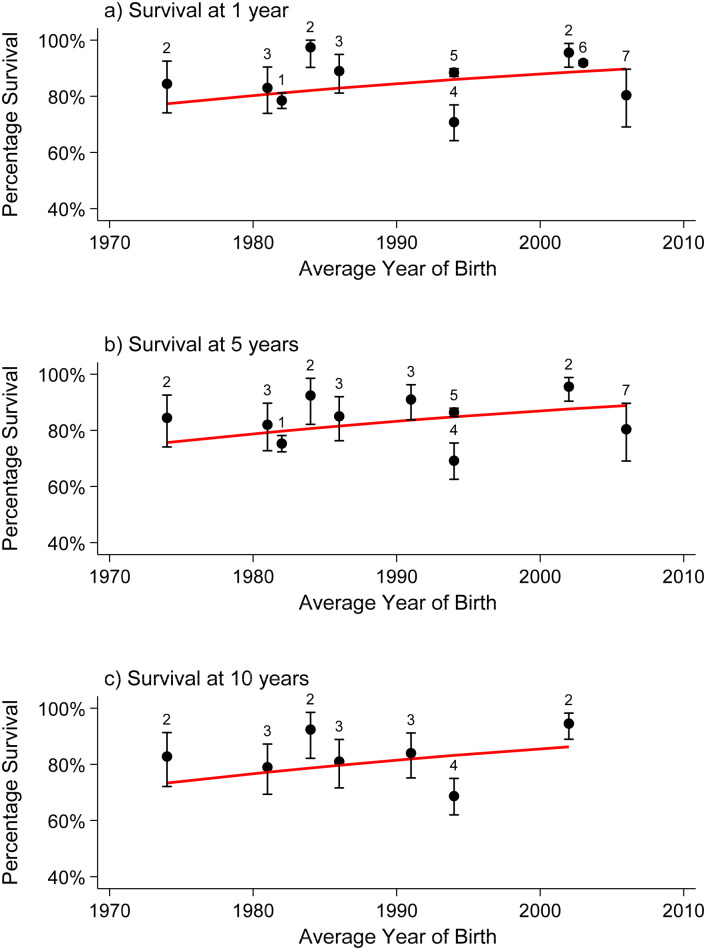

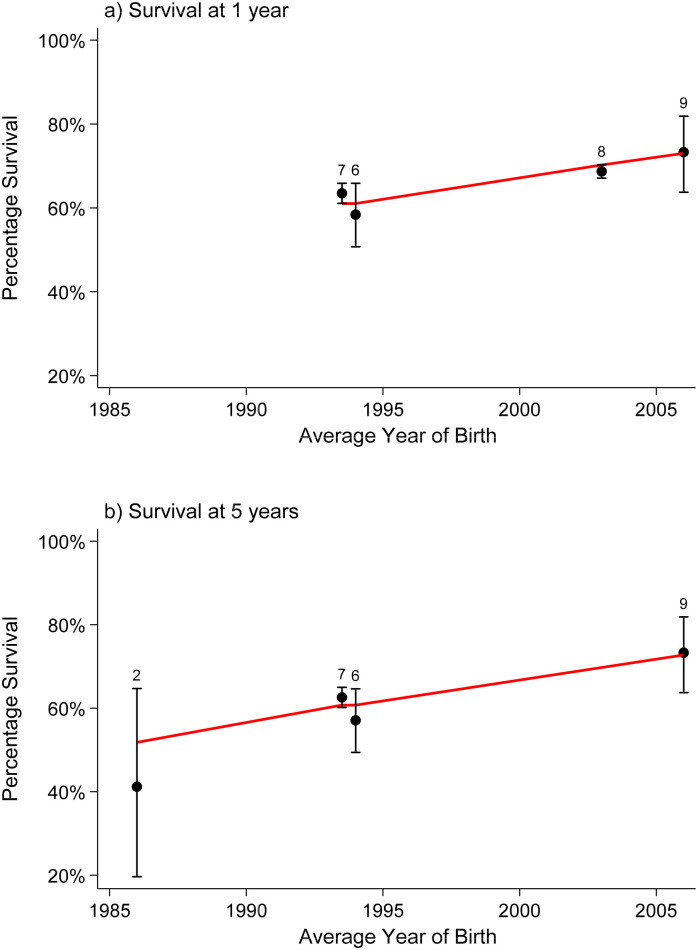

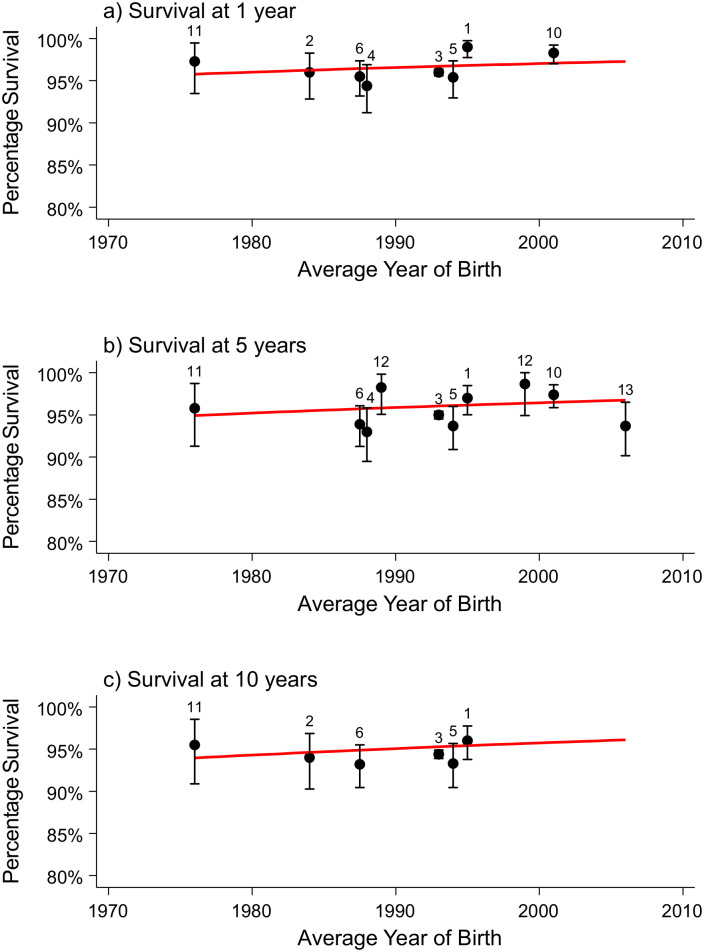

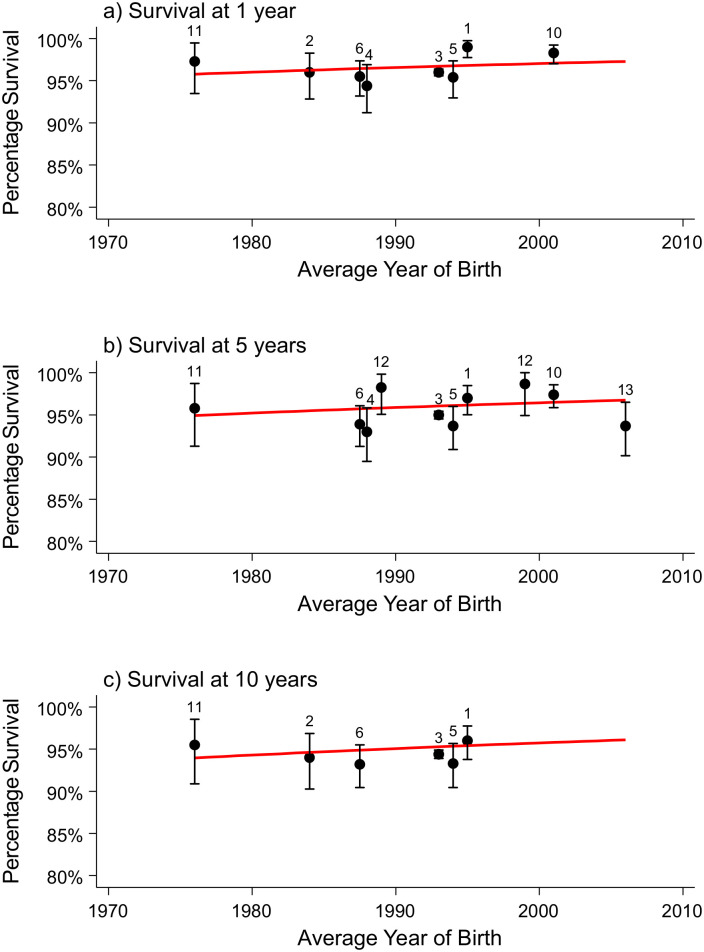

Seven studies of survival in children born with spina bifida [6,15,40–42,45,48] including 7,422 live births were summarised in a meta-analysis, with pooled survival estimates of 92%, 91%, 89%, and 88% at ages 5, 10, 20, and 25 years predicted for children born in 2020 (Table 3). Survival has improved significantly over time, with an increased OR per 10-year increase in birth year 1.34 (95% CI 1.24–1.46, p < 0.001) (Table 3 and Fig 2).

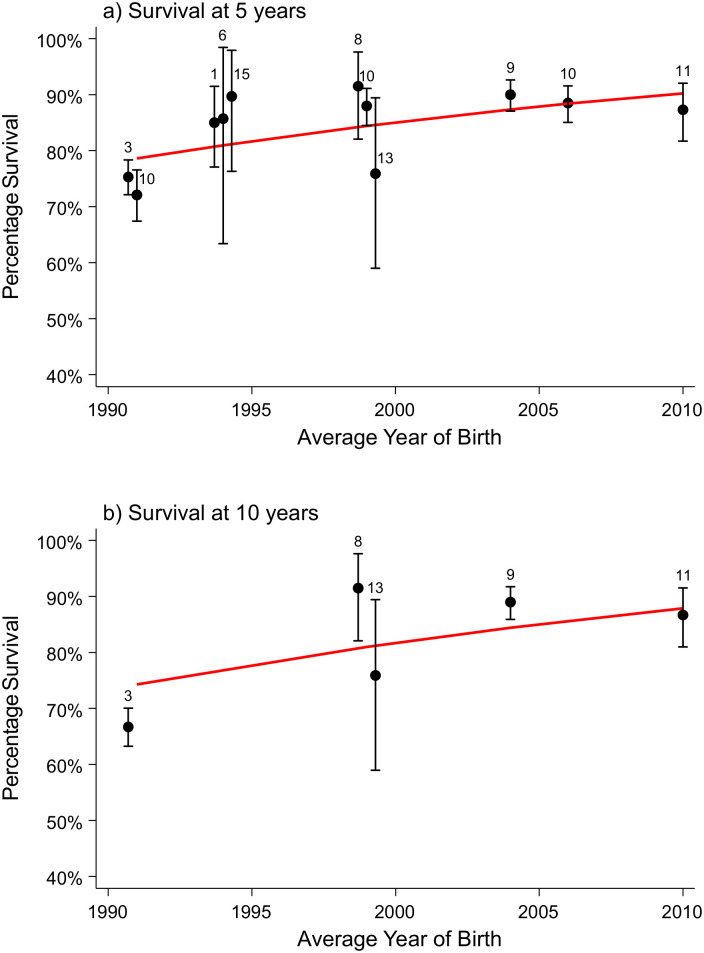

Table 3. Predicted survival estimates for children born with selected congenital anomalies in 2000 and 2020 (results of the meta-analysis).

| Congenital anomaly subtype (n of studies) | Survival period | Survival estimates for infants born in 2000, % | Survival estimates for infants born in 2020, % | Trend in survival over time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative odds (95% confidence interval) | p-Value | ||||

| Spina bifida (n = 7) | 1.34 (1.24–1.46)* | <0.001 | |||

| 1 year | 88 (87–89) | 93 (91–94) | |||

| 5 years | 87 (86–88) | 92 (90–94) | |||

| 10 years | 86 (84–87) | 91 (89–93) | |||

| 20 years | 82 (80–85) | 89 (86–92) | |||

| 25 years | 81 (77–83) | 88 (84–91) | |||

| Encephalocele (n = 4) | 0.98 (0.95–1.01)* | 0.19 | |||

| 1 year | 73 (73–74) | 73 (71–74) | |||

| 5 years | 73 (73–74) | 72 (71–74) | |||

| 10 years | 73 (72–74) | 72 (70–74) | |||

| 20 years | 72 (71–73) | 71 (69–74) | |||

| 25 years | 72 (71–73) | 71 (68–74) | |||

| Oesophageal atresia (n = 7) | 1.50 (1.38–1.62)* | <0.001 | |||

| 1 year | 86 (85–87) | 93 (92–94) | |||

| 5 years | 86 (85–87) | 93 (91–94) | |||

| 10 years | 85 (84–87) | 93 (91–94) | |||

| 20 years | 85 (82–87) | 92 (90–94) | |||

| 25 years | 84 (82–87) | 92 (89–94) | |||

| Biliary atresia (n = 14) | |||||

| Overall survival | 1.62 (1.28–2.05)* | <0.001 | |||

| 1 year | 87 (85–90) | 95 (90–97) | |||

| 5 years | 85 (81–89) | 94 (87–97) | |||

| 10 years | 82 (74–87) | 92 (83–97) | |||

| 20 years | 73 (59–84) | 88 (70–96) | |||

| Survival with native liver | 0.96 (0.88–1.03)* | 0.26 | |||

| 1 year | 44 (41–47) | 41 (35–48) | |||

| 5 years | 43 (38–47) | 41 (33–49) | |||

| 10 years | 42 (36–48) | 40 (30–50) | |||

| 20 years | 40 (31–50) | 38 (26–52) | |||

| Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (n = 9) | 1.57 (1.37–1.81)* | <0.001 | |||

| 1 year | 67 (66–69) | 84 (78–88) | |||

| 5 years | 67 (65–69) | 83 (78–88) | |||

| 10 years | 67 (64–69) | 83 (77–88) | |||

| 20 years | 66 (63–69) | 83 (76–88) | |||

| 25 years | 66 (62–69) | 83 (75–88) | |||

| Gastroschisis (n = 5) | |||||

| 1 year | 90 (90–91) | 94 (90–96) | 1.24 (1.02–1.50)* | 0.029 | |

| 5 years | 90 (89–91) | 93 (89–96) | |||

| 10 years | 89 (87–91) | 93 (88–96) | |||

| 20 years | 88 (84–90) | 92 (85–95) | |||

| Down syndrome (n = 10) | |||||

| With congenital heart defect (CHD) | 1.99 (1.67–2.37)* | < 0.001 | |||

| 1 year | 92 (91–93) | 98 (97–99) | |||

| 5 years | 90 (88–92) | 97 (95–99) | |||

| 10 years | 88 (84–92) | 97 (93–98) | |||

| 20 years | 87 (76–93) | 96 (90–99) | |||

| Without CHD | 1.17 (0.91–1.5)* | 0.23 | |||

| 1 year | 97 (96–98) | 98 (95–99) | |||

| 5 years | 96 (95–98) | 97 (94–99) | |||

| 10 years | 96 (92–98) | 97 (91–99) | |||

| 20 years | 95 (85–98) | 96 (82–99) | |||

| Trisomy 18 (n = 4) | Not tested | ||||

| 1 year | 15 (14–17) | ||||

| 5 years | 14 (12–16) | ||||

| 10 years | 13 (11–16) | ||||

*Per 10-year increase compared to any previous birth cohort.

Fig 2. Survival estimates (with 95% confidence intervals) of children with spina bifida at 1 (a), 5 (b), and 10 (c) years of age over time (10 birth cohorts from 7 studies).

The numbers at survival points indicate the included study, which may appear more than once if survival was reported for more than one birth cohort: 1 –Agha, 2006, Canada; 2 –Borgstedt-Bakke, 2017, western Denmark; 3 –Wong, 2001, Atlanta, USA; 4 –Tennant, 2010, Northern England; 5 –Wang, 2011; USA, 6 –Wang, 2015, USA; 7 –Schneuer, 2019, New South Wales, Australia.

Four studies [15,40,41,47] reported survival of 1,562 encephalocele live births, with pooled survival estimates of 72%, 72%, 71%, and 71% at ages 5, 10, 20, and 25 years predicted for infants born in 2020 (Table 3). A small decrease in survival was observed over time, which was not statistically significant (p = 0.19) but was included in the model predictions to be consistent with the models for other congenital anomalies and acknowledging that the power from analysing only 4 studies is very low (Table 3 and S1 Fig).

Survival in individuals with hydrocephalus was reported in four studies, with the three more recent studies reporting very similar survival rates at age 5 years [15,40,42] and at 15 years in two studies with longer follow-up. The earlier study (1967–1979) reported lower survival of 50.8% for male individuals by age 18 years [8] (Table 2). Comparison of survival between these studies is difficult owing to differences in the inclusion criteria.

Orofacial clefts

Seven studies providing survival estimates for children born with orofacial clefts [6,15–17,40–42] included 32,492 live births. There was insufficient number of studies reporting data by specific cleft type that met criteria for a meta-analysis; therefore, the survival data are presented in Table 2. Generally, 1-year and long-term survival of children with isolated cleft lip is over 99% [15,16], about 96%–97% for isolated cleft palate [15,16] and much lower for non-isolated orofacial cleft types [40,41].

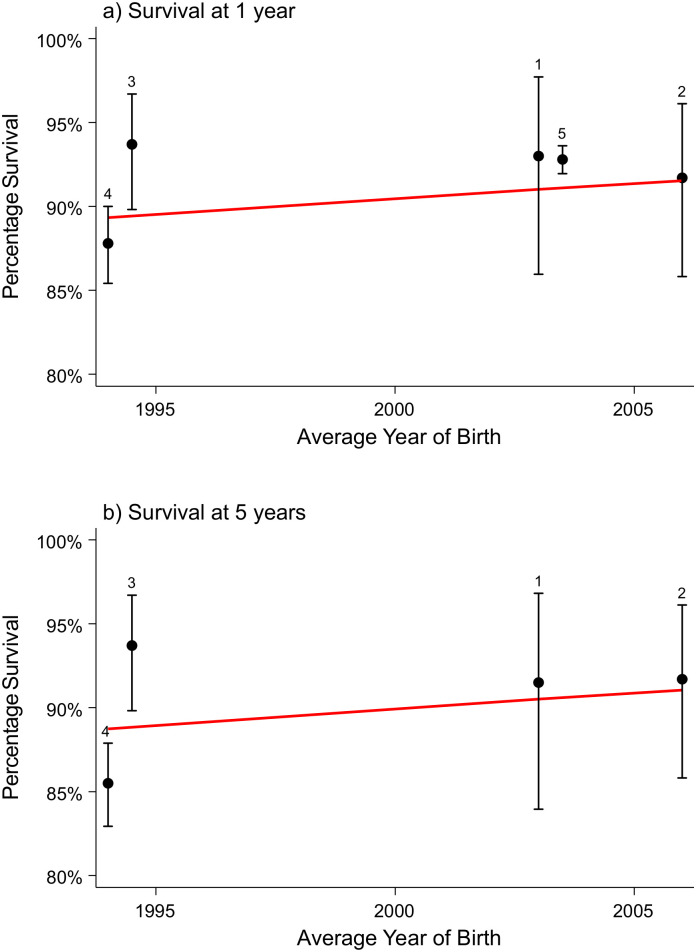

Anomalies of the digestive system

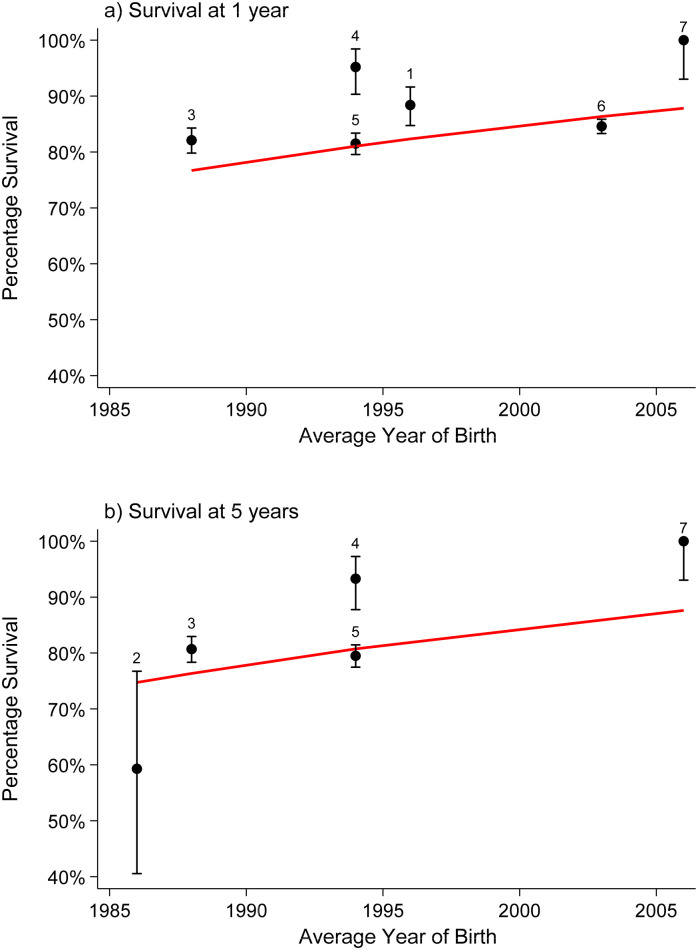

Seven studies reporting survival in children with oesophageal atresia (n = 6,303) were summarised in a meta-analysis [9,15,40–42,50,51]. There was a statistically significant improvement in survival over time, with an increased OR of 1.50 (95% CI 1.38–1.62, p < 0.001) per 10-year increase in birth year. The pooled survival estimates predicted for infants born in 2020 were 93%, 93%, 92%, and 92% at ages 5, 10, 20, and 25 years, respectively (Table 3 and Fig 3).

Fig 3. Survival estimates (with 95% confidence intervals) of children with oesophageal atresia at 1 (a) and 5 (b) years of age over time (7 studies).

The numbers at survival points indicate the included study: 1 –Cassina, 2016, Northeast Italy; 2 –Garne, 2002, Funen, Denmark; 3 –Oddsberg, 2012, Sweden; 4 –Tennant, 2010, Northern England; 5 –Wang, 2011 USA; 6 –Wang, 2015, USA; 7 –Schneuer, 2019, New South Wales, Australia.