Abstract

Purpose

We assessed the associations between population-based polygenic risk scores (PRS) for breast (BC) or epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) with cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers.

Methods

Retrospective cohort data on 18,935 BRCA1 and 12,339 BRCA2 female pathogenic variant carriers of European ancestry were available. Three versions of a 313 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) BC PRS were evaluated based on whether they predict overall, estrogen receptor (ER)–negative, or ER-positive BC, and two PRS for overall or high-grade serous EOC. Associations were validated in a prospective cohort.

Results

The ER-negative PRS showed the strongest association with BC risk for BRCA1 carriers (hazard ratio [HR] per standard deviation = 1.29 [95% CI 1.25–1.33], P = 3×10−72). For BRCA2, the strongest association was with overall BC PRS (HR = 1.31 [95% CI 1.27–1.36], P = 7×10−50). HR estimates decreased significantly with age and there was evidence for differences in associations by predicted variant effects on protein expression. The HR estimates were smaller than general population estimates. The high-grade serous PRS yielded the strongest associations with EOC risk for BRCA1 (HR = 1.32 [95% CI 1.25–1.40], P = 3×10−22) and BRCA2 (HR = 1.44 [95% CI 1.30–1.60], P = 4×10−12) carriers. The associations in the prospective cohort were similar.

Conclusion

Population-based PRS are strongly associated with BC and EOC risks for BRCA1/2 carriers and predict substantial absolute risk differences for women at PRS distribution extremes.

Key words: BRCA1/2, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, PRS, genetics

INTRODUCTION

Pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are associated with high risk of developing breast and ovarian cancers.1,2 A recent study of BRCA1/2 carriers estimated the average risk of developing breast cancer by age 80 years to be 72% for BRCA1 and 69% for BRCA2 carriers.2 Corresponding ovarian cancer risks were 44% for BRCA1 and 17% for BRCA2 carriers. This and previous studies have demonstrated that cancer risks for BRCA1/2 carriers increase with an increasing number of affected first- or second-degree relatives,2 suggesting genetic or other familial factors modify cancer risks for BRCA1/2 carriers. Consistent with this observation, common breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in the general population, have been shown to modify breast and ovarian cancer risks for BRCA1/2 carriers.3–7

Polygenic risk scores (PRS) based on the combined effects of disease-associated SNPs, can lead to significant levels of breast and ovarian cancer risk stratification in the general population.8,9 It has also been demonstrated that PRS can result in large absolute risk differences of developing these cancers for BRCA1/2 carriers.10 The largest study to date was a retrospective cohort study of 23,463 carriers using a PRS based on up to 88 breast cancer susceptibility SNPs and a PRS based on up to 17 ovarian cancer susceptibility SNPs.10

Recent population-based GWAS identified an additional 72 breast and 12 ovarian cancer susceptibility SNPs.6,7,11 Based on these data, PRS have been constructed that include SNPs associated at both genome-wide and sub-genome-wide significance levels. The best performing PRS for breast cancer includes 313 SNPs.12

It is therefore important to understand how the most recently developed breast and ovarian cancer PRS modify cancer risks for BRCA1/2 carriers, as this information will be necessary for implementation studies to evaluate how their application influences cancer risk management for women with pathogenic variants in these genes. In this study, we used the largest sample of women with pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants currently available to assess the associations between the most recently developed PRS with cancer risks for BRCA1/2 carriers. We evaluated how these PRS associations vary with age, cancer family history, and BRCA1/2 gene variant characteristics. We further validated the associations for the first time in a prospective cohort of carriers and investigated implications for cancer risk prediction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Retrospective cohort study participants

Study participants were enrolled through 63 studies from 29 countries contributing to the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA).13 Eligibility was restricted to women who were ≥18 years old at recruitment and carried a pathogenic BRCA1/2 variant. CIMBA collected information on year of birth, variant description, age at study recruitment and last follow-up, age at breast and ovarian cancer (including invasive ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal) diagnosis, age/date at bilateral prophylactic mastectomy, and number of first- and second-degree relatives with breast or ovarian cancer. Related individuals were tracked through a unique family identifier. The majority of study participants were recruited through cancer genetics clinics and enrolled in regional or national research studies. Variants were categorized according to their predicted or known effect on cellular protein expression: class I included loss-of-function pathogenic variants expected to result in unstable or no protein; class II included variants likely to yield stable mutant proteins.14 Breast cancer pathology data were available from pathology reviews, tumor registry records, medical records or pathology records, and from tissue microarray immunohistochemical staining.15

The genotyping, quality control and imputation processes have been described in detail previously6,7 (brief description provided in supplement). The present study was restricted to carriers of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants of European ancestry, determined using genetic data and multidimensional scaling.6,7

Breast cancer PRS

The methods for calculating the PRS are described in the Supplementary material. We evaluated three versions of the published breast cancer PRS based on the same 313 SNPs, with different weights optimized to predict the risk of overall (PRSBC), ER-negative (PRSER-), or ER-positive (PRSER+) breast cancer12 (Table S1).

The breast cancer PRS were standardized using the standard deviations (SDs) of the corresponding PRS in population-based controls. Therefore, the estimated hazard ratios (HRs) from this study are directly comparable with odds ratios (ORs) estimated from population-based data.12

Epithelial ovarian cancer PRS

We constructed ovarian cancer PRS based on ovarian cancer susceptibility SNPs identified through GWAS.7 Two ovarian cancer PRS were constructed: one for all invasive epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) using 30 SNPs (PRSEOC); and one for predicting high-grade serous (HGS) EOC using 22 SNPs (PRSHGS) (Supplementary material, Table S2). HGS is the predominant EOC histotype in BRCA1/2 tumors.16

The PRS SDs in unaffected women in our sample were used to standardize PRSEOC and PRSHGS.

Associations between PRS and breast cancer risk

Associations between PRS and breast cancer risk for BRCA1/2 carriers were assessed using the CIMBA retrospective cohort. Study participants were censored at the first of (1) breast cancer diagnosis, (2) ovarian cancer diagnosis, (3) risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy, (4) last follow-up, or (5) age 80 years. Participants with a first breast cancer diagnosis were considered affected. To account for nonrandom sampling with respect to disease status, associations were evaluated using weighted Cox regression.17,18 This involved assigning age- and disease-specific sampling weights, such that observed weighted age-specific incidences agreed with established incidences for BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant carriers (Supplementary material).19

We assessed the associations between three breast cancer PRS with the risk of overall breast cancer, and separately with ER-positive or ER-negative breast cancer risk. Models were stratified by country and Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry and were adjusted for birth cohort and the first four ancestry informative principal components calculated separately by genotyping array (Supplementary material). We fitted models adjusting for family history of breast cancer in first- and second-degree relatives to determine whether cancer family history was a confounder of PRS associations. Family history was coded as no family history, or one relative, or two or more relatives diagnosed with breast cancer. Robust variances were calculated to account for the inclusion of related individuals by clustering on family membership. All models were fitted separately in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers.

We fitted separate models in which the PRS was assumed to be (1) continuous and (2) categorical based on PRS percentiles determined by the PRS distribution in unaffected carriers. We tested for variation in the association of the PRS by age by fitting Cox regression models in which the PRS was a time-varying covariate, with age as the time scale, that included a PRS main effect and a PRS-by-age interaction term. Heterogeneity in the associations across countries was assessed by fitting models with a PRS–country interaction term. A likelihood ratio test (LRT) was used to assess statistical significance of interaction terms by comparing the models with the interaction against a model without the interaction term (Supplementary material). Similarly, LRTs were used to compare the fit of nested models.

Previous studies have demonstrated that cancer risks for BRCA1/2 carriers vary by pathogenic variant location or functional effect.2,20 To investigate whether the PRS associations varied by BRCA1/2-variant location, we fitted models that included a PRS by location interaction. Variants were grouped into regions by nucleotide position on the basis of previously reported differences in breast or ovarian cancer risks. BRCA1 variants were grouped in three regions (5’ to c.2281, c.2282 to c.4071, and c.4072 to 3’).20,21 The BRCA2 ovarian cancer cluster region (OCCR) was used to define the variant location groups.20,22 Two BRCA2 OCCR definitions were used: “narrow” (5’ to c.3846, c.3847 to c.6275, c.6276 to 3’) and “wide” (5’ to c.2831, c.2832 to c.6401, c.6402 to 3’). We also investigated variation in PRS associations by the predicted variant effect on protein stability/expression (class I versus class II, defined above).

To assess the associations with ER-specific breast cancer risk, a similar censoring process was used except the event of interest was diagnosis of either ER-positive or ER-negative breast cancer. Affected carriers with the alternative ER status to the outcome of interest were censored at that diagnosis. Carriers with missing ER status were excluded from the analysis.

Associations with epithelial ovarian cancer risk

The associations with EOC risk were evaluated following a similar process. However, women were censored at bilateral risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) rather than bilateral mastectomy. Carriers with a first ovarian cancer diagnosis were assumed to be affected in this analysis. We also fitted models that adjusted for family history of ovarian cancer in first- and second-degree relatives, coded as no family history, or one relative, or two or more relatives diagnosed with the disease.

The discriminatory ability of each PRS was assessed by Harrell’s C-statistic23 stratified by country and Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry and adjusted for birth cohort and principal components.24 Standard errors were estimated using 1000 bootstrap replications.

Validation in prospective cohorts

The PRS associations were further evaluated using prospective cohort data. The prospective cohort included pathogenic variant carriers from the BRCA1 and BRCA2 Cohort Consortium (BBCC)2 and CIMBA13 who were unaffected at recruitment (informed consent and baseline questionnaire). The BBCC included data from the International BRCA1/2 Carrier Cohort Study (IBCCS), Breast Cancer Family Registry (BCFR), and the Kathleen Cunningham Foundation Consortium for Research into Familial Breast Cancer (kConFab) (details in Supplementary material).2 Only women of European ancestry were included in the analysis. All prospective cohort participants were genotyped as part of the CIMBA effort described above. However, prospective analyses considered only the prospective follow-up period from the time at recruitment of each participant into the study. Thus, the analysis time considered in the prospective and retrospective analyses were completely distinct. Associations were evaluated using Cox regression, separately for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. The censoring process and analysis are described in detail in the Supplementary material.

Predicted age-specific cancer risks by PRS

Retrospective analysis HR estimates were used to predict age-specific absolute risks of developing breast and ovarian cancer by PRS percentiles following a previously published method.25 To ensure consistency with known cancer risks for BRCA1/2 carriers, average age-specific cancer incidences were constrained over PRS percentile categories to agree with external estimates of cancer incidences for carriers2 (Supplementary material). We also calculated absolute breast cancer risks for carriers in the absence or presence of cancer family history and by BRCA2 variant location, assuming external average cancer incidences by family history and variant location.2 The absolute risks were used to calculate 10-year cancer risks at each age by different PRS percentiles (Supplementary material).

Ethics statement

All study participants provided written informed consent and participated in research or clinical studies at the host institute under ethically approved protocols. The studies and their approving institutes are listed as a separate online Supplement (Ethics Statement).

All statistical tests were two-sided. Retrospective and prospective cohort analyses were performed using R 3.5.1. Age-varying PRS and discrimination analyses were conducted using Stata 13.1 (Supplementary material).

RESULTS

The CIMBA retrospective cohort consisted of 18,935 BRCA1 carriers (9473 diagnosed with breast and 2068 with ovarian cancer) and 12,339 BRCA2 carriers (6332 with breast and 718 with ovarian cancer, Table S3).

The SNPs included in the PRS were well imputed on both genotyping platforms (Supplementary material, Figs. S1, S2, Tables S1, S2). The average PRS were larger for women diagnosed with cancer, compared with unaffected carriers (Table S3), but the PRS SDs were similar in unaffected and affected carriers (Table S3).

Associations with breast cancer risk

Table 1 shows the associations between PRSBC, PRSER-, and PRSER+ and overall breast cancer risk for carriers using the CIMBA retrospective cohort data. PRSER- yielded the strongest association for BRCA1 carriers (per SD HR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.25–1.33, P = 3×10−72). For BRCA2 carriers, the strongest associations were found for PRSBC (per SD HR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.27–1.36, P = 7×10−50) and PRSER+ (per SD HR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.26–1.36, P = 6×10−49). Adjusting for breast cancer family history yielded similar associations between the PRS and breast cancer risk to those observed in the unadjusted models (Table 1). Family history was significantly associated with risk in all models.

Table 1.

PRS associations with breast and ovarian cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers using the CIMBA retrospective cohort data.

| BRCA1 carriers | BRCA2 carriers | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No FHa adjustment | FH adjusted | No FH adjustment | FH adjusted | ||||||||

| Outcome | PRS | Unaffected/ affected | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | Unaffected/ affected | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Breast cancer | BC | 9462/ 9473 | 1.20 (1.17–1.23) | 1.15×10−39 | 1.20 (1.17–1.23) | 9.54×10−40 | 6007/ 6332 | 1.31 (1.27–1.36) | 7.11×10−50 | 1.31 (1.26–1.36) | 6.54×10−48 |

| ER- | 1.29 (1.25–1.33) | 3.03×10−72 | 1.29 (1.25–1.33) | 1.02×10−71 | 1.23 (1.19–1.28) | 4.06×10−29 | 1.23 (1.18–1.27) | 6.72×10−28 | |||

| ER+ | 1.17 (1.14–1.20) | 6.93×10−29 | 1.17 (1.14–1.20) | 5.50×10−29 | 1.31 (1.26–1.36) | 6.12×10−49 | 1.30 (1.26–1.35) | 5.10×10−47 | |||

| ER-negative breast cancer | BC | 10,138/ 3263 | 1.09 (1.05–1.13) | 3.69×10−6 | 1.09 (1.05–1.13) | 4.44×10−6 | 8049/ 703 | 1.20 (1.11–1.30) | 4.90×10−6 | 1.19 (1.10–1.29) | 1.91×10−5 |

| ER- | 1.23 (1.18–1.28) | 2.39×10−27 | 1.23 (1.18–1.27) | 1.08×10−26 | 1.31 (1.21–1.43) | 1.15×10−10 | 1.29 (1.19–1.41) | 9.98×10−10 | |||

| ER+ | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | 4.58×10−3 | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | 4.93×10−3 | 1.17 (1.08–1.26) | 1.36×10−4 | 1.15 (1.07–1.25) | 3.91×10−4 | |||

| ER-positive breast cancer | BC | 12,376/ 1025 | 1.44 (1.35–1.53) | 3.88×10−28 | 1.44 (1.35–1.54) | 1.25×10−27 | 6440/ 2312 | 1.37 (1.31–1.44) | 2.95×10−40 | 1.36 (1.30–1.43) | 6.28×10−38 |

| ER- | 1.29 (1.21–1.38) | 2.94×10−15 | 1.29 (1.21–1.37) | 9.25×10−15 | 1.22 (1.16–1.28) | 1.93×10−15 | 1.21 (1.15–1.27) | 1.54×10−14 | |||

| ER+ | 1.44 (1.35–1.54) | 3.94×10−28 | 1.45 (1.35–1.54) | 1.12×10−27 | 1.38 (1.32–1.45) | 1.88×10−42 | 1.37 (1.31–1.44) | 5.99×10−40 | |||

| Ovarian cancer | EOC | 16,867/ 2068 | 1.31 (1.24–1.39) | 1.49×10−21 | 1.31 (1.24–1.39) | 2.36×10−21 | 11,621/ 718 | 1.43 (1.29–1.59) | 1.81×10−11 | 1.42 (1.28–1.58) | 3.40×10−11 |

| HGS | 1.32 (1.25–1.40) | 3.01×10−22 | 1.32 (1.25–1.40) | 5.18×10−22 | 1.44 (1.30–1.60) | 4.34×10−12 | 1.43 (1.29–1.59) | 7.54×10−12 | |||

BC breast cancer, CI confidence interval, CIMBA Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2, ER- estrogen receptor negative, ER+ estrogen receptor positive, EOC epithelial ovarian cancer, FH family history, HGS high-grade serous, HR hazard ratio, PRSpolygenic risk score.

Rows in bold represent the best performing PRS for each particular outcome.

aFamily history in first- and second-degree relatives: coded as no family history, or one relative, or two or more relatives diagnosed with the disease.

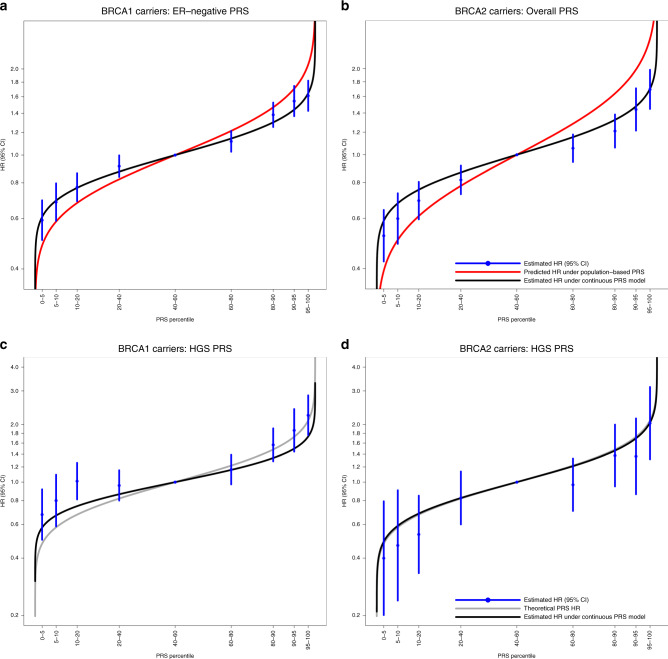

The PRSER- and PRSBC were used for subsequent BRCA1 and BRCA2 carrier analyses, respectively. There was no statistically significant evidence of heterogeneity in the country-specific HR estimates (BRCA1 PLRT = 0.26, BRCA2 PLRT = 0.64; Fig. S3). The estimated HRs for each PRS percentile category (Table 2) were consistent with the HRs predicted under models with the continuous PRS (estimated above), but were attenuated compared to the HRs expected under the population-based PRS distributions (Fig. 1a, b). Models estimating PRS percentile-specific associations did not fit significantly better than models in which PRS were continuous (BRCA1 carriers PLRT = 0.18; BRCA2 carriers PLRT = 0.99). The HRs for the breast cancer association decreased with age (Table 2; PRS-by-age interaction HRs: BRCA1 HR = 0.996, P = 0.003; BRCA2 HR = 0.994, P = 9.40×10−5). The HRs for the PRS associations with breast cancer risk did not differ by variant location (Table 2: BRCA1 PLRT = 0.17; BRCA2 PLRT ≥ 0.27). However, the associations differed by the predicted effect of the gene variant on protein stability/expression: the HRs for the PRS associations with breast cancer risk were larger for carriers with class II (stable mutant proteins) versus class I (unstable/no protein) variants (Table 2, BRCA1: class I HR = 1.26 [95% CI = 1.22–1.30], class II HR = 1.38 [1.30–1.46], Pdifference = 0.011; BRCA2: class I HR = 1.30 [95% CI = 1.25–1.35], class II HR = 1.72 [95% CI = 1.44–2.06], Pdifference = 0.003).

Table 2.

Categorical PRS, age-varying and pathogenic variant characteristic specific PRS associations with cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers, using data from the CIMBA retrospective cohort.

| Breast cancer | Ovarian cancer | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 carriers: PRSER- | BRCA2 carriers: PRSBC | BRCA1 carriers: PRSHGS | BRCA2 carriers: PRSHGS | ||||||||||

| Model | Category | HR (95% CI) | P | PLRT | HR (95% CI) | P | PLRT | HR (95% CI) | P | PLRT | HR (95% CI) | P | PLRT |

| Categorical PRS percentiles (%) | 0–5 | 0.59 (0.50–0.70) | 0.52 (0.42–0.64) | 0.68 (0.50–0.92) | 0.40 (0.20–0.79) | ||||||||

| 5–10 | 0.69 (0.59–0.80) | 0.60 (0.49–0.73) | 0.80 (0.59–1.09) | 0.47 (0.24–0.91) | |||||||||

| 10–20 | 0.77 (0.69–0.86) | 0.69 (0.59–0.80) | 1.01 (0.81–1.26) | 0.53 (0.33–0.85) | |||||||||

| 20–40 | 0.91 (0.84–1.00) | 0.82 (0.73–0.92) | 0.96 (0.80–1.15) | 0.83 (0.60–1.14) | |||||||||

| 40–60 | 1.00 [reference] | 1.00 [reference] | 1.00 [reference] | 1.00 [reference] | |||||||||

| 60–80 | 1.12 (1.03–1.21) | 1.05 (0.94–1.18) | 1.16 (0.97–1.39) | 0.97 (0.71–1.33) | |||||||||

| 80–90 | 1.38 (1.25–1.53) | 1.21 (1.06–1.38) | 1.57 (1.28–1.91) | 1.38 (0.95–2.00) | |||||||||

| 90–95 | 1.55 (1.37–1.75) | 1.44 (1.21–1.71) | 1.86 (1.44–2.41) | 1.36 (0.86–2.15) | |||||||||

| 95–100 | 1.61 (1.43–1.82) | 1.69 (1.45–1.98) | 2.24 (1.76–2.84) | 2.03 (1.31–3.15) | |||||||||

| Age-varying PRSa: model including a main PRS effect and a PRS × age interaction term | PRS | 1.517 (1.359–1.694) | 1.04×10−13 | 0.017 | 1.721 (1.498–1.977) | 1.75×10−14 | 2.27×10−3 | 1.507 (1.125–2.020) | 6.02×10−3 | 0.41 | 2.183 (1.263–3.774) | 5.17×10−3 | 0.44 |

| PRS × age | 0.996 (0.993–0.999) | 3.27×10−3 | 0.994 (0.991–0.997) | 9.40×10−5 | 0.997 (0.991–1.003) | 0.35 | 0.992 (0.982–1.003) | 0.14 | |||||

| Gene pathogenic variant class | Class I | 1.26 (1.22–1.30) | 0.011b | 5.29×10−3 | 1.30 (1.25–1.35) | 3.20×10−3 b | 0.046 | 1.33 (1.24–1.43) | 0.85b | 0.85 | N/Ac | ||

| Class II | 1.38 (1.30–1.46) | 1.72 (1.44–2.06) | 1.32 (1.18–1.47) | ||||||||||

| BRCA1 pathogenic variant location | c.2282-c.4071 | 1.25 (1.19–1.31) | 0.17 | N/A | 1.50 (1.35–1.66) | 8.73×10−3 | N/A | ||||||

| 5’ to c.2281 | 1.28 (1.22–1.34) | 1.30 (1.18–1.42) | |||||||||||

| c.4072 to 3′ | 1.34 (1.28–1.41) | 1.21 (1.10–1.33) | |||||||||||

| BRCA2 pathogenic variant location (narrow) | c.3847-c.6275 | N/A | 1.30 (1.23–1.38) | 0.27 | N/A | 1.48 (1.24–1.76) | 0.96 | ||||||

| 5’ to c.3846 | 1.26 (1.17–1.34) | 1.41 (1.17–1.69) | |||||||||||

| c.6276 to 3′ | 1.37 (1.29–1.46) | 1.43 (1.20–1.70) | |||||||||||

| BRCA2 pathogenic variant location (wide) | c.2831-c.6401 | N/A | 1.29 (1.23–1.36) | 0.33 | N/A | 1.48 (1.26–1.75) | 0.90 | ||||||

| 5’ to c.2830 | 1.26 (1.17–1.37) | 1.37 (1.13–1.68) | |||||||||||

| c.6402 to 3′ | 1.37 (1.29–1.46) | 1.43 (1.20–1.71) | |||||||||||

Class I pathogenic variant refers to loss-of-function pathogenic variants expected to result in unstable or no protein; class II pathogenic variant refers to pathogenic variants likely to yield stable mutant proteins. P value for the Wald test statistic unless otherwise stated.LRT compares the models with an interaction term against the model without the interaction term.

BC breast cancer, CI confidence interval, CIMBA Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2, ER- estrogen receptor negative, HGS high-grade serous, HR hazard ratio, LRT likelihood ratio test, N/A not applicable.

aAge in years.

bP value for the difference in HR for class I carriers vs. the HR for class II carriers.

cNumber of affected class II carriers was too small to make meaningful inference.

Fig. 1. Associations with specific polygenic risk score (PRS) percentiles.

The PRS percentile thresholds were determined in the sets of unaffected carriers for the disease under assessment. Table 2 shows the estimated hazard ratios (HRs). The black curve represents the expected HRs assuming the per standard deviation HR estimates in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers based on the continuous PRS models (Table 1). (a) PRSER- percentile-specific associations with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 carriers. The red curve represents the expected HRs over the PRS percentile distribution, assuming the per SD odds ratio (OR) estimate from the population-based validation studies from Mavaddat et al.12 (OR = 1.45 per PRSER- standard deviation). (b) PRSBC percentile-specific associations with breast cancer risk for BRCA2 carriers. The red curve represents the expected HRs over the PRS percentile distribution, assuming the per SD OR estimate from the population-based validation studies from Mavaddat et al.12 (OR = 1.61 per PRSBC standard deviation). (c) PRSHGS percentile-specific associations with ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 carriers. (d) PRSHGS percentile-specific associations with ovarian cancer risk for BRCA2 carriers. The gray curve (c and d only) represents the theoretical HRs across the PRS distribution, calculated by assuming external single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) effect sizes and allele frequencies for SNPs contributing to the PRS. CI confidence interval, ER estrogen receptor, HGS high-grade serous.

Under the age-varying PRS models, the C-statistic for PRSER- was 0.60 (95% CI = 0.59–0.61) for BRCA1 carriers, and for the PRSBC for BRCA2 carriers 0.65 (95% CI = 0.63–0.67). Under models that did not include the age-varying PRS, the estimated C-statistics were 0.58 (95% CI = 0.57–0.59) and 0.60 (95% CI = 0.59–0.62) for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers, respectively.

Associations with ER-specific breast cancer risk

The strongest PRS associations with ER-negative disease were observed for PRSER- for both BRCA1 (per SD HR = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.18–1.28, P = 2×10−27) and BRCA2 (HR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.21–1.43, P = 1×10−10) carriers (Table 1). The PRSBC and PRSER+ showed the strongest associations with ER-positive disease for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with similar HR estimates for PRSBC and PRSER+ (Table 1). The associations remained similar after adjusting for family history of breast cancer (Table 1).

Associations with epithelial ovarian cancer risk

The 30-SNP PRSEOC was strongly associated with EOC risk for BRCA1 (per SD HR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.24–1.39, P = 1×10−21) and BRCA2 (per SD HR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.29–1.59, P = 2×10−11) carriers (Table 1). The 22-SNP PRSHGS, based only on SNPs showing associations with high-grade serous EOC, showed similar associations (Table 1, BRCA1 HR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.25–1.40, P = 3×10−22; BRCA2 HR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.30–1.60, P = 4×10−12). Adjusting for family history of ovarian cancer yielded similar associations to unadjusted models (Table 1).

PRSHGS was used for downstream analyses for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. There was no evidence of heterogeneity in the PRSHGS associations across countries (Fig. S3: BRCA1 PLRT = 0.08; BRCA2 PLRT = 0.97). For both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers the estimated HRs by PRS percentile categories (Table 2) were consistent with those expected under the theoretical population-based PRS distributions (Fig. 1c, d). There was no evidence that the PRSHGS association with EOC risk varied by age (BRCA1 P = 0.35; BRCA2 P = 0.14). The associations between PRSHGS and EOC risk varied by BRCA1 variant location (PLRT = 8.7×10−3), with a larger HR for variants in the central region of BRCA1 (central region HR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.35–1.66; 5’ to c.2281 region HR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.18–1.42; c.4072 to 3’ region HR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.10–1.33). There was little evidence to support differences in the associations by BRCA2 variant location (Table 2). There was no evidence of differences in the associations by the BRCA1 variant predicted effect on protein expression (Pdifference = 0.85).

The C-statistics for PRSHGS were estimated to be 0.604 (95% CI = 0.582–0.626) for BRCA1 and 0.667 (95% CI = 0.636–0.699) for BRCA2 carriers.

Prospective cohort associations

The breast cancer prospective cohort included 2088 BRCA1 carriers with 297 incident cases and 1757 BRCA2 carriers with 215 incident cases (Table S4). The PRSER- was associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 carriers (per SD HR = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.14–1.44, P = 4.4×10−5). For BRCA2 carriers, PRSBC was associated with breast cancer risk with a per SD HR = 1.36 (95% CI = 1.17–1.57, P = 4.3×10−5) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations of the best performing PRS in the prospective cohort of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers.

| Outcome | PRS | Number of women at risk | Incident cancers | HR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | BRCA1 carriers | ER- | 2088 | 297 | 1.28 (1.14–1.44) | 4.44×10−5 |

| BRCA2 carriers | BC | 1757 | 215 | 1.36 (1.17–1.57) | 4.26×10−5 | |

| Ovarian cancer | BRCA1 carriers | HGS | 3152 | 108 | 1.28 (1.06–1.55) | 1.08×10−2 |

| BRCA2 carriers | HGS | 2495 | 56 | 1.45 (1.13–1.86) | 3.29×10−3 |

Number of women at risk is the number of pathogenic variant carriers unaffected at baseline. Incident cancers is the number of women who developed breast/ovarian cancer during the follow-up period.

BC breast cancer, CI confidence interval, ER- estrogen receptor negative, HGS high-grade serous, HR hazard ratio, PRS polygenic risk score.

The ovarian cancer prospective cohort comprised 3152 BRCA1 carriers with 108 incident cases and 2495 BRCA2 carriers with 56 incident cases (Table S4). The PRSHGS was associated with EOC risk for both BRCA1 (HR = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.06–1.55, P = 0.011) and BRCA2 (HR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.13–1.86, P = 0.003) carriers (Table 3).

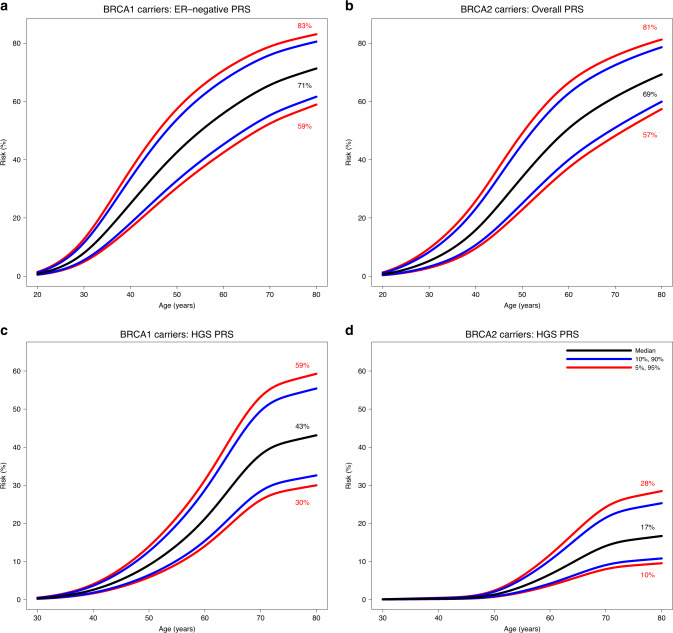

Absolute risks of cancer by PRS percentiles

We estimated age-specific and 10-year absolute risks of developing breast and ovarian cancers across different PRS percentiles (Figs. 2 and S4). BRCA1 carriers at the 5th and 95th percentiles of the PRSER- distribution were predicted to have breast cancer risks to age 80 years of 59% and 83%, respectively. The corresponding risks for BRCA2 carriers based on PRSBC were 57% and 81%. Although PRS associations were not altered by family history adjustment in the models, and there was no significant evidence of interaction between PRS and variant location, both of these factors remain significant predictors of breast cancer risk (in addition to PRS). Therefore, family history and variant location can be considered jointly with the PRS to predict cancer risks for BRCA1/2 carriers (Figs. S5–S9). For example, breast cancer risk to age 80 years for BRCA2 carriers with no family history at the 5th and 95th percentiles of the PRS were predicted to be 43% and 67%, respectively, compared with 62% and 85% for those with a family history. The risks of developing ovarian cancer by age 80 years were 30% and 59% for BRCA1 carriers at the 5th and 95th percentiles of the PRSHGS distribution. The corresponding risks for BRCA2 carriers were 10% and 28%, respectively.

Fig. 2. Predicted absolute risks of developing breast and ovarian cancer by polygenic risk score (PRS) percentile.

Risks were calculated assuming the retrospective cohort hazard ratio (HR) estimates (Tables 1, 2). (a) Predicted absolute risks of developing breast cancer for BRCA1 carriers by percentiles of the PRSER-. (b) Predicted absolute risks of developing breast cancer for BRCA2 carriers by percentiles of the PRSBC. (c) Predicted absolute risks of developing ovarian cancer for BRCA1 carriers by the percentiles of the PRSHGS. (d) Predicted absolute risks of developing ovarian cancer for BRCA2 carriers by percentiles of the PRSHGS. ER estrogen receptor, HGS high-grade serous.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the associations between a recently reported PRS for breast cancer, based on 313 SNPs, and a PRS for EOC, based on 30 SNPs, with cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. The associations were evaluated in a large retrospective cohort and separately in a prospective cohort of BRCA1/2 carriers.

The results demonstrate that the PRS developed using population-based data are also associated with breast and ovarian cancer risk for women with BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants. The PRS developed for predicting ER-negative breast cancer showed the strongest association with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 carriers, while for BRCA2 carriers the PRS developed for predicting overall breast cancer risk performed best. The associations were unchanged after adjusting for cancer family history and were similar between the retrospective and prospective studies. There was evidence that the magnitude of the PRS associations decreased with increasing age for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. There was evidence for differences in associations by the predicted effects of variants on protein stability/expression, with the breast cancer PRS having a larger effect for carriers of variants predicted to yield a stable protein. For ovarian cancer, the PRS developed for predicting overall or HGS EOC demonstrated similar evidence of association with EOC risk, for both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. The results are consistent with findings from a previous CIMBA study, based on fewer samples and fewer SNPs, which demonstrated that PRS can lead to large differences in absolute risks of developing breast and ovarian cancers for female BRCA1/2 carriers.10

The estimated HR associations for the PRS with breast cancer risk from this study were smaller than the estimated ORs from the population-based study in which they were derived.12 This difference is unlikely to be an overestimation of the ORs in the general population (“winner’s curse”26), because the effect sizes were estimated in prospective studies that were independent of the data used in their development.12,27 Adjustment for family history, a potential confounder in this study, did not influence the associations. Therefore, these most likely represent real differences, in which PRS modify breast cancer risk for BRCA1/2 carriers to a smaller relative extent than the general population. This meaningful attenuation must be considered when using population-based PRS to predict breast cancer risk for BRCA1/2 carriers and should be incorporated into breast cancer risk prediction models.28

The departure from the multiplicative model for the joint effects of PRS (or some subset of SNPs) and BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants might simply reflect the high absolute risks for BRCA1/2 carriers. That is, women with the highest polygenic risk are likely to develop breast cancer at a young age, so that the relative risk associated with the PRS will diminish with age. It is interesting that the decreasing age effect appeared stronger for carriers than the general population, while the relative risk below age 50 years was more comparable with that seen in the general population.12 We found that the breast cancer HRs were significantly elevated for carriers of variants that are predicted to generate a stable mutant protein (class II variants). These elevated HRs were similar to the corresponding ORs for association between the PRS and ER-negative (OR = 1.47) and ER-positive (OR = 1.74) breast cancer reported in the general population.12 The vast majority of individuals in the general population would be expected to be noncarriers with intact BRCA1/2 protein expression in at-risk tissues, so this observation suggests that some SNPs in the PRS may exert their effect on proteins that interact with stable wildtype or mutant BRCA1 or BRCA2 protein.

We used the ER-specific PRS to assess associations with ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancer for BRCA1/2 carriers. As expected, the PRS developed for ER-positive breast cancer in the general population was the most predictive of ER-positive breast cancer risk for both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers, and the PRS developed for ER-negative breast cancer was the most predictive of ER-negative breast cancer for both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers, in line with known differences in ER expression between BRCA1- and BRCA2-related tumors.29,30 These results suggest that further risk prediction improvements can be achieved by estimating the risk of developing ER-specific breast cancer for BRCA1/2 carriers.

Unlike the breast cancer PRS, no systematic evaluation of EOC PRS has been reported in the general population. We therefore included only SNPs identified through GWAS for EOC and its histotypes, using the reported effect sizes as PRS weights. We found that a PRS constructed on the basis of the associations between SNPs and HGS EOC was the most predictive for both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers, in line with the fact that the majority of tumors in both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers are HGS.15 The estimated HR for PRSHGS was larger for BRCA2 carriers compared with the BRCA1 carrier HR estimate. This pattern had been observed previously, based on a smaller sample size and fewer SNPs, but the difference between the HRs observed here is smaller than that reported previously.10

Predicted absolute risks for BRCA1 carriers at the 5th and 95th PRS percentiles at age 50 years varied from 31% to 58% for breast, and from 5% to 13% for ovarian cancer. By age 80 years, they varied from 59% to 83% for breast and from 30% to 59% for ovarian cancer. The corresponding absolute risks for BRCA2 carriers by age 50 years ranged from 23% to 49% and by age 80 years from 57% to 81% for breast cancer. The ovarian cancer risks by age 80 years varied from 10% to 28%. We also observed differences in the 10-year age-specific risks of cancer for different PRS distribution percentiles (Fig. S4). For example, the estimated 10-year risk of developing breast cancer at age 40 years was 17% and 34% for BRCA1 carriers at the 5th and 95th percentiles of the PRS for ER-negative breast cancer, respectively. We found no significant attenuation of the PRS associations when adjusting for family history, and no evidence of interaction between PRS and pathogenic variant location. However, family history and variant location are both associated with cancer risk for BRCA1/2 carriers.2,20–22 Taken together, the results suggest that when family history and PRS are considered jointly, or when variant location and PRS are considered jointly, both factors influence the risk of developing breast cancer for BRCA1/2 carriers. As a consequence, the differences in absolute risk become larger when the PRS is considered together with family history or variant location (Figs. S5–S9) and demonstrate that the PRS should be considered in combination with other risk factors to provide comprehensive cancer risks for BRCA1/2 carriers.

Strengths of this study include the large cohort sample sizes of BRCA1/2 carriers and use of independent prospective cohort data to validate PRS associations with cancer risks. The similarity in association estimates between the retrospective and prospective analyses suggests that retrospective estimates have not been strongly influenced by potential biases (e.g., survival bias). As the PRS analyzed in this study were originally developed and validated in population-based studies, the associations reported here represent independent evaluations of the PRS in BRCA1/2 carriers. The analyses were also adjusted for cancer family history, hence associations are unlikely to be biased due to confounding.

Limitations of this study include the fact that tumor ER status information was missing on a substantial proportion of the study population. Therefore, we were unable to assess associations with ER-specific breast cancer in the entire sample of BRCA1/2 carriers. The use of PRS developed in the general population means that if there are BRCA1- or BRCA2-specific modifier SNPs,4,5 these may not have been included in the PRS. Therefore, alternative approaches should also investigate developing PRS using data directly from BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers, although much larger sample sizes will be required. We did not present confidence intervals for the predicted PRS-specific absolute risks of breast or ovarian cancer, and the absolute PRS-specific risks by variant location and family history. These predictions critically depend on external cancer incidence estimates for BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant carriers,2 which themselves are uncertain and therefore should only be used as a general guide. Future studies should aim to factor in uncertainty in the predicted risks based on all parameters. In addition, the PRS-specific absolute cancer risks overall and by family history or pathogenic variant location should be validated in much larger prospective studies of unaffected carriers. Finally, the present analyses were limited to carriers of European ancestry. Hence the results presented may not be applicable to BRCA1/2 carriers of Asian, African, and other non-European ancestries.

PRS are now being used in risk-stratified screening trials and other implementation studies in the general population.31 They are commercially available and have been incorporated in comprehensive cancer risk prediction models.28,32 The findings of this study indicate that these PRS, in combination with established risk modifiers (e.g. family history and pathogenic variant characteristics) can be used to provide more personalized cancer risk predictions for carriers, which may assist clinical management decisions. It is therefore important to undertake relevant implementation studies to determine the optimal way of incorporating these PRS into genetic counseling and risk management, and to assess whether PRS on their own or in combination with other risk factors influence the short- or long-term clinical management decisions that female BRCA1/2 carriers make. Furthermore, the available risk models incorporating the effects of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants28,32 and PRS should be validated in large prospective studies of carriers.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Full acknowledgements and funding details can be found in the Supplementary material. The following consortia and studies contributed to this research and are listed as authors: The Genetic Modifiers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 (GEMO) Study Collaborators: Pascaline Berthet, Chrystelle Colas, Marie-Agnès Collonge-Rame, Capucine Delnatte, Laurence Faivre, Paul Gesta, Sophie Giraud, Christine Lasset, Fabienne Lesueur, Véronique Mari, Noura Mebirouk, Emmanuelle Mouret-Fourme, Hélène Schuster, Dominique Stoppa-Lyonnet. Epidemiological Study of Familial Breast Cancer (EMBRACE) Collaborators: Julian Adlard, Munaza Ahmed, Antonis Antoniou, Daniel Barrowdale, Paul Brennan, Carole Brewer, Jackie Cook, Rosemarie Davidson, Douglas Easton, Ros Eeles, D. Gareth Evans, Debra Frost, Helen Hanson, Louise Izatt, Kai-ren Ong, Lucy Side, Aoife O’Shaughnessy-Kirwan, Marc Tischkowitz, Lisa Walker. Kathleen Cuningham Foundation Consortium for research into Familial Breast cancer (kConFab) Investigators: Georgia Chenevix-Trench, Kelly-Anne Phillips, Amanda Spurdle. Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Research Group Netherlands (HEBON) Investigators: Marinus Blok, Peter Devilee, Frans Hogervorst, Maartje Hooning, Marco Koudijs, Arjen Mensenkamp, Hanne Meijers-Heijboer, Matti Rookus, Klaartje van Engelen. French National BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations carrier cohort (GENEPSO) Investigators: Nadine Andrieu, Catherine Noguès. The Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 (CIMBA): All authors are members of CIMBA.

Disclosure

G.P. has received honoraria from Novartis, Amgen, Roche, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Daniel R. Barnes, Email: drb54@medschl.cam.ac.uk.

GEMO Study Collaborators:

Pascaline Berthet, Chrystelle Colas, Marie-Agnès Collonge-Rame, Capucine Delnatte, Laurence Faivre, Sophie Giraud, Christine Lasset, Véronique Mari, Noura Mebirouk, Emmanuelle Mouret-Fourme, Hélène Schuster, and Dominique Stoppa-Lyonnet

EMBRACE Collaborators:

Julian Adlard, Munaza Ahmed, Antonis Antoniou, Daniel Barrowdale, Paul Brennan, Carole Brewer, Jackie Cook, Rosemarie Davidson, Douglas Easton, Ros Eeles, D. Gareth Evans, Debra Frost, Helen Hanson, Louise Izatt, Kai-ren Ong, Lucy Side, Aoife O’Shaughnessy-Kirwan, Marc Tischkowitz, and Lisa Walker

kConFab Investigators:

Georgia Chenevix-Trench, Kelly-Anne Phillips, and Amanda Spurdle

HEBON Investigators:

Marinus Blok, Peter Devilee, Frans Hogervorst, Maartje Hooning, Marco Koudijs, Arjen Mensenkamp, Hanne Meijers-Heijboer, Matti Rookus, and Klaartje van Engelen

GENEPSO Investigators:

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41436-020-0862-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Antoniou A, Pharoah PDP, Narod S, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case Series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1117–1130. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, et al. Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA. 2017;317:2402–2416. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antoniou AC, Spurdle AB, Sinilnikova OM, et al. Common breast cancer-predisposition alleles are associated with breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:937–948. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couch FJ, Wang X, McGuffog L, et al. Genome-wide association study in BRCA1 mutation carriers identifies novel loci associated with breast and ovarian cancer risk. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaudet MM, Kuchenbaecker KB, Vijai J, et al. Identification of a BRCA2-specific modifier locus at 6p24 related to breast cancer risk. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milne RL, Kuchenbaecker KB, Michailidou K, et al. Identification of ten variants associated with risk of estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1767–1778. doi: 10.1038/ng.3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phelan CM, Kuchenbaecker KB, Tyrer JP, et al. Identification of 12 new susceptibility loci for different histotypes of epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat Genet. 2017;49:680–691. doi: 10.1038/ng.3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mavaddat N, Pharoah PDP, Michailidou K, et al. Prediction of breast cancer risk based on profiling with common genetic variants. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv036. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang X, Leslie G, Gentry-Maharaj A, et al. Evaluation of polygenic risk scores for ovarian cancer risk prediction in a prospective cohort study. J Med Genet. 2018;55:546–554. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuchenbaecker KB, McGuffog L, Barrowdale D, et al. Evaluation of polygenic risk scores for breast and ovarian cancer risk prediction in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109:djw302. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michailidou K, Lindström S, Dennis J, et al. Association analysis identifies 65 new breast cancer risk loci. Nature. 2017;551:92–94. doi: 10.1038/nature24284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mavaddat N, Michailidou K, Dennis J, et al. Polygenic risk scores for prediction of breast cancer and breast cancer subtypes. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chenevix-Trench G, Milne RL, Antoniou AC, et al. An international initiative to identify genetic modifiers of cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 (CIMBA) Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:104. doi: 10.1186/bcr1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antoniou AC, Sinilnikova OM, Simard J, et al. RAD51 135G–>C modifies breast cancer risk among BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from a combined analysis of 19 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1186–1200. doi: 10.1086/522611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mavaddat N, Barrowdale D, Andrulis IL, et al. Pathology of breast and ovarian cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:134–147. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lakhani SR, Manek S, Penault-Llorca F, et al. Pathology of ovarian cancers in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2473–2481. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antoniou AC, Goldgar DE, Andrieu N, et al. A weighted cohort approach for analysing factors modifying disease risks in carriers of high-risk susceptibility genes. Genet Epidemiol. 2005;29:1–11. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes DR, Lee A, Investigators E, kConFab I, Easton DF, Antoniou AC. Evaluation of association methods for analysing modifiers of disease risk in carriers of high-risk mutations. Genet Epidemiol. 2012;36:274–291. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antoniou AC, Cunningham AP, Peto J, et al. The BOADICEA model of genetic susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancers: updates and extensions. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1457–1466. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rebbeck TR, Mitra N, Wan F, et al. Association of type and location of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with risk of breast and ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2015;313:1347–1361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson D, Easton D, Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Variation in BRCA1 cancer risks by mutation position. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson D, Easton D, Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Variation in cancer risks, by mutation position, in BRCA2 mutation carriers. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:410–419. doi: 10.1086/318181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrell FE. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA. 1982;247:2543–2546. doi: 10.1001/jama.1982.03320430047030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White IR, Rapsomaniki E, Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration Covariate-adjusted measures of discrimination for survival data. Biom J. 2015;57:592–613. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201400061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antoniou AC, Beesley J, McGuffog L, et al. Common breast cancer susceptibility alleles and the risk of breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: implications for risk prediction. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9742–9754. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao R, Boehnke M. Quantifying and correcting for the winner’s curse in genetic association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2009;33:453–462. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Läll K, Lepamets M, Palover M, et al. Polygenic prediction of breast cancer: comparison of genetic predictors and implications for risk stratification. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:557. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5783-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee A, Mavaddat N, Wilcox AN, et al. BOADICEA: a comprehensive breast cancer risk prediction model incorporating genetic and nongenetic risk factors. Genet Med. 2019;1708–1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Mavaddat N, Barrowdale D, Andrulis IL, et al. Pathology of breast and ovarian cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:134–147. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee AJ, Cunningham AP, Kuchenbaecker KB, et al. BOADICEA breast cancer risk prediction model: updates to cancer incidences, tumour pathology and web interface. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:535–545. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antoniou A, Anton-Culver H, Borowsky A, et al. A response to “Personalised medicine and population health: breast and ovarian cancer”. Hum Genet. 2019;138:287–289. doi: 10.1007/s00439-019-01984-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.IBIS. IBIS breast cancer risk evaluation tool. 2017. http://www.ems-trials.org/riskevaluator/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.