Abstract

Structured reporting is a favorable and sustainable form of reporting in radiology. Among its advantages are better presentation, clearer nomenclature, and higher quality. By using MRRT-compliant templates, the content of the categorized items (e.g., select fields) can be automatically stored in a database, which allows further research and quality analytics based on established ontologies like RadLex® linked to the items. Additionally, it is relevant to provide free-text input for descriptions of findings and impressions in complex imaging studies or for the information included with the clinical referral. So far, however, this unstructured content cannot be categorized. We developed a solution to analyze and code these free-text parts of the templates in our MRRT-compliant reporting platform, using natural language processing (NLP) with RadLex® terms in addition to the already categorized items. The established hybrid reporting concept is working successfully. The NLP tool provides RadLex® codes with modifiers (affirmed, speculated, negated). Radiologists can confirm or reject codes provided by NLP before finalizing the structured report. Furthermore, users can suggest RadLex® codes from free text that is not correctly coded with NLP or can suggest to change the modifier. Analyzing free-text fields took 1.23 s on average. Hybrid reporting enables coding of free-text information in our MRRT-compliant templates and thus increases the amount of categorized data that can be stored in the database. This enhances the possibilities for further analyses, such as correlating clinical information with radiological findings or storing high-quality structured information for machine-learning approaches.

Keywords: Structured reporting, Natural language processing, RadLex, Medical informatics, Database

Introduction

Communicating the results of a diagnostic study is a crucial part of a radiologist’s work [1]. The radiological report is the vehicle to communicate imaging findings and its interpretation in the clinical context [2]. In most cases, the written report represents the best way to transmit information to the referrer [1]. These reports are usually created by speech recognition and range from being little structured to unstructured. Radiologists often use subjective phrases in their reports without formal consensus on their meaning or impact. Lee et al. asked radiologists and clinical referrers about the meaning of such phrases and concluded that certain phrases such as “evidence of” or “may represent” carry different connotations for radiologists and clinicians [2].

In 2018, the European Society of Radiology published a paper on structured reporting (SR) in radiology, defining it as a key element of optimizing the work of radiologists [3]. SR can be described in several stages with an increasing degree of standardization with regard to structure and terminology. Beyond that, the term “structured reporting” can also mean the use of templates in a reporting platform with an affiliated database for further analysis.

Studies have shown the advantages of structured reports in subspecialties including musculoskeletal radiology and oncological, urogenital, and abdominal imaging, among others [4–7]. Structured reports of pancreatic cancer contain significantly more key features and essential information for surgical planning than free-text reports [7]. Schoeppe et al. compared structured reports of CT staging of lymphomas with free-text reports [5]. Four hematologists scored the reports using a questionnaire addressing completeness, structure, guidance of patient management, and overall quality. SR led to quicker information extraction and better comprehensibility [5].

Furthermore, referrals stated that structured reports addressed the clinical question significantly better than did free-text reports and enabled faster decisions for clinical management [5]. Folio et al. asked radiologists and oncologists to assess the adequacy of the current radiology report and found that most oncologists agreed that traditional text-only and qualitative reports are not sufficient for assessing tumor burden [8].

Sobez et al. showed that it is feasible to automatically deliver highly qualified reports in different languages through SR [9]. Structured reports enable new opportunities for epidemiological research by storing the structured information in a database, as has already been shown to be beneficial in pulmonary embolism [10]. Such databases enable selection of training cases for medical education or suitable cases for the training and validation of artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms.

Using structured reports in clinical routine requires their implementation in the current radiology workflow [3]. The IHE MRRT integration profile specifies the roles of the different actors involved in creating report templates [3, 11]. Using standard web technologies, Pinto et al. showed the feasibility of developing an IHE MRRT-compliant platform for structured reports and integrating it into the clinical workflow [12]. Currently, we can store all information gathered from check boxes, drop-down menus, and measurements in the database of our in-house reporting platform linked to RadLex® [12]. However, even structured reports contain free-text passages to describe complex findings and to specifically answer the question raised by the referring physician. Completing the picture would require coding these free-text parts to store them in a structured manner in the database. Furthermore, information from the clinical referrer is not structured, so structuring this information automatically is also crucial.

Natural language processing (NLP) involves automatically translating natural language text into a standardized format and using it for decision support [13]. NLP can be applied in radiology to analyze findings regarding certain questions, e.g., a radiologist’s recommendation, evaluation of text variation in reports, flagging of critical findings in the impression section, or extraction of the codes from a clinical coding system [14–16]. RadLex® is a specialized radiologic lexicon that contains concepts with definitions and synonyms as well as their relations [17]. NLP makes it possible to extract RadLex® concepts from radiological free-text reports [18].

The aim of this study was to show the feasibility of hybrid reporting—the combination of SR and NLP—by using an NLP-enabled MRRT-compliant reporting platform to increase structured content in a database that allows for more in-depth research and quality assurance.

Methods

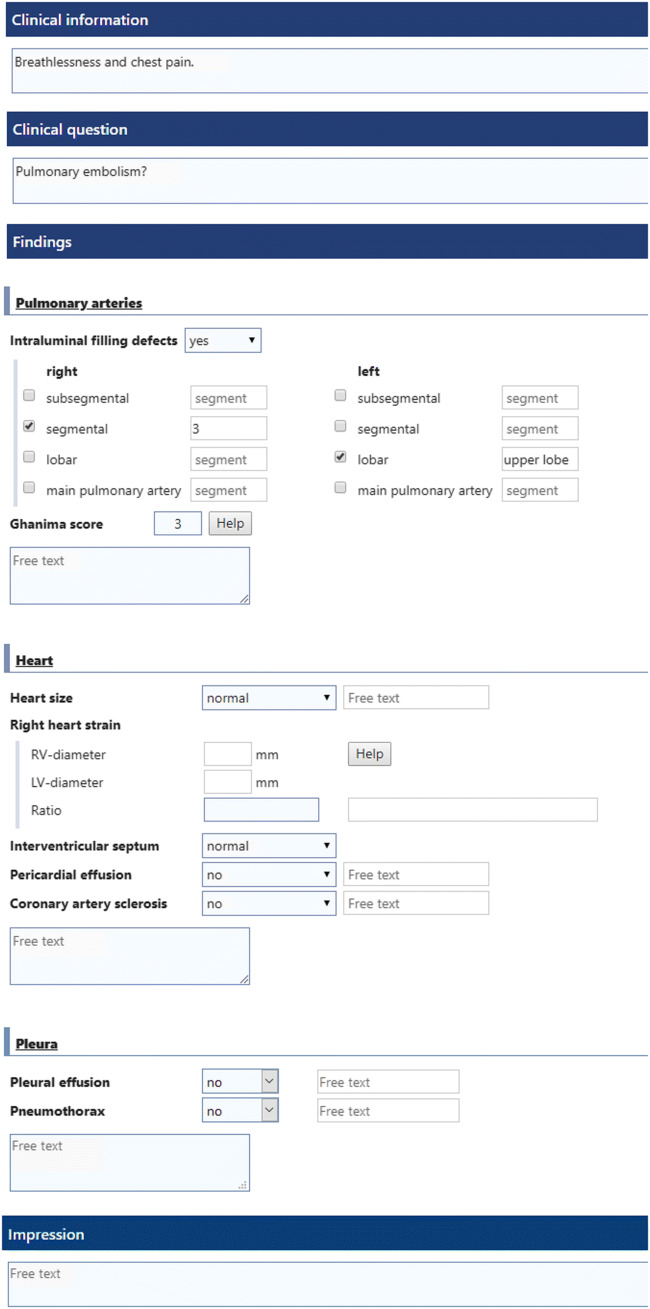

In our institution, we have a long-standing experience in SR. We have been using structured reports for several indications, e.g., for CT in suspected pulmonary artery embolism (Fig. 1) or in suspected urolithiasis, duplex sonography of the carotid arteries, or in context of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver transplantation regarding the German Transplantation Act, for the last 5 years [10, 12, 19]. Our reporting platform is fully integrated into our radiological information system (i-Solutions, Mannheim, Germany) as well as into our department’s picture archiving and communication system (Sectra AB, Linköping, Sweden).

Fig. 1.

Excerpt from the template for SR of suspected pulmonary artery embolism on CT used in our department. Unstructured clinical information and the clinical question provided by the referring physician were automatically sent from the hospital information system to the reporting platform. Most fields contain structured information, as intraluminal filling defects of the pulmonary arteries (yes or no) or the size of the heart (normal or enlarged). Additional free-text fields enable the input of unstructured additional information that cannot be provided in the form of checkboxes or select-fields. At our institution, we decided to use free-text in the impression section to generate an individualized answer to the clinical question.

Each MRRT template can contain multiple codes from different code designators, e.g., DICOM Controlled Terminology, RadLex®, or ICD-10 German (known as DMDICD10). The codes belong directly to the whole template, a template field, or an option from a select field. The links to the codes can contain an optional term type, which describes the context from the code, e.g., modality or body part [11]. For each imported MRRT template, a content table is created. The types and IDs of the template fields define the data types and names for the columns. A report contains exactly one content entity.

Unstructured information from the referrer is sent by the hospital information system (SAP SE, Walldorf, Germany) into the reporting templates. In our hospital, we decided to use free-text fields in the findings and impression sections. Speech recognition can be used to fill these free-text fields. To analyze these passages, we used the online healthcare analytics services of Empolis Information Management (Kaiserslautern, Germany). Automatically analyzing natural language is not trivial, so we implemented a function to accept or reject codes generated by NLP as well as a function to add codes.

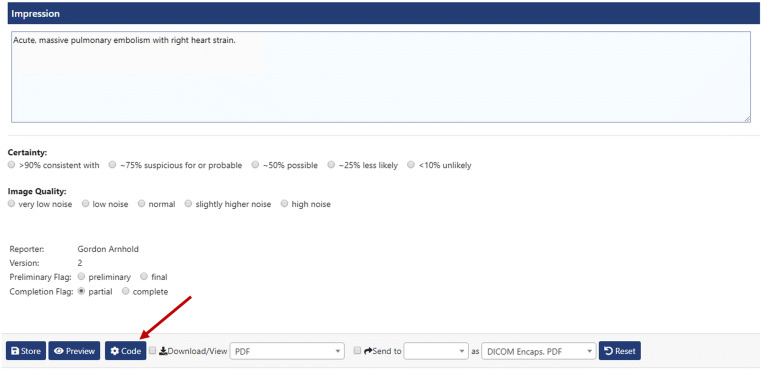

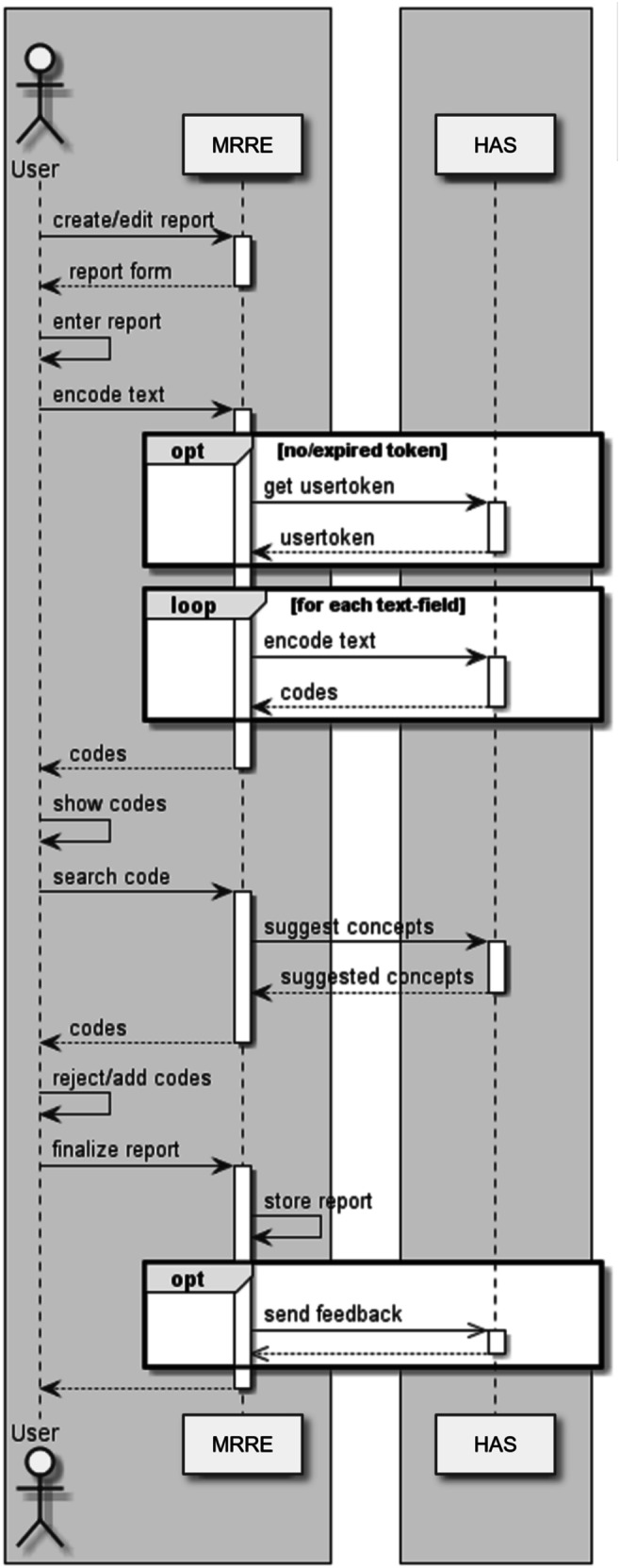

We integrated the NLP function (Fig. 2) into our IHE MRRT-compliant open-source web-based reporting platform (MRRE, Mainz Radiology Reporting Engine) [12]. For coding of all free-text content, every multiline text field is first sent to the MRRE server. Coding means that free text is translated into RadLex® codes to structure this information and enable further analyses. After authentication at the server of the Empolis Healthcare Analytics Services (HAS), the content for each free-text field then is sent to service (Fig. 3). Each free-text field contained unstructured information, i.e., narrative text. HAS implements a common NLP pipeline consisting of cleansing (e.g., replacement of abbreviations), contextualization (e.g., into segments “clinical information,” “findings,” and “conclusion”), concept recognition using RadLex®, and negation detection (“affirmed,” “negated,” and “speculated”).

Fig. 2.

Integration of the NLP function. The “Code” button (red arrow) has been added to our internal reporting platform. Coding can be performed before the structured report is saved and translates all unstructured free-text into RadLex® codes

Fig. 3.

NLP sequence diagram showing interactions among the user (radiologist), the Mainz Radiology Reporting Engine (MRRE), and the Empolis Healthcare Analytics Services (HAS) with authentications, coding, and feedback function. All analytics as concept recognition using RadLex® were performed by the HAS

The results are collected, parsed, and sent to the browser for further review by the reporting physician.

Results

Integrating the NLP functionality in our reporting platform was feasible. We designated this process “hybrid reporting” because it contains the best of both worlds in reporting: structured and conventional free-text reporting. Our solution can generate RadLex® codes (German and English) as well as ICD codes (German) for each free-text field used in our templates, with one additional click before the report is finalized.

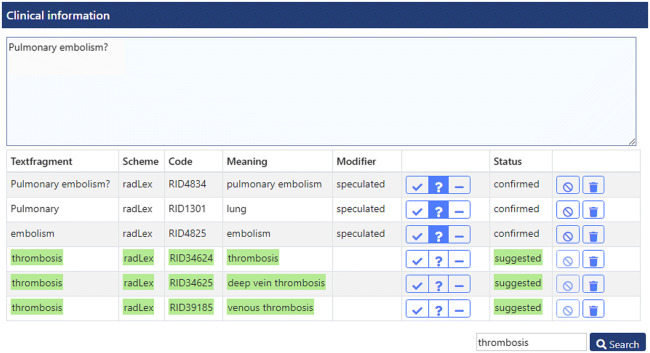

A table containing all text fragments, terms with code, modifier, and status is displayed below each of the free-text fields that contain information. The reporter can confirm or reject generated codes and suggest additional codes (Fig. 4). The radiologist can revise the modifier of the generated RadLex® code (e.g., from “affirmed” to “negated”). After the structured report is saved, the feedback is automatically sent to the HAS. Confirmed codes were stored in our database to enable analysis for quality measurements or epidemiological research.

Fig. 4.

After the HAS translated the free-text information into structured information, radiologists are able to confirm or reject the generated RadLex® codes displayed below each corresponding free-text field. The user is able to change the modifier and choose among “affirmed,” “speculated,” and “negated.” Furthermore, the radiologist can suggest additional RadLex® codes (as in this case of thrombosis) by typing the term into the search field

After implementation, we coded 15 reports of low-dose CT examinations in patients with suspected urolithiasis to evaluate the time required. Each of these 15 cases was coded five times. As a use case, the reports were randomly selected out of more than 800 structured reports of the retroperitoneum stored in the MRRE written by more than ten different radiologists. Mean number of words was 11 for the clinical information section and 20 for the conclusion section. Generating of codes by NLP took on average of 1.23 s (minimum 0.91 s, maximum 2.87 s) in these test cases.

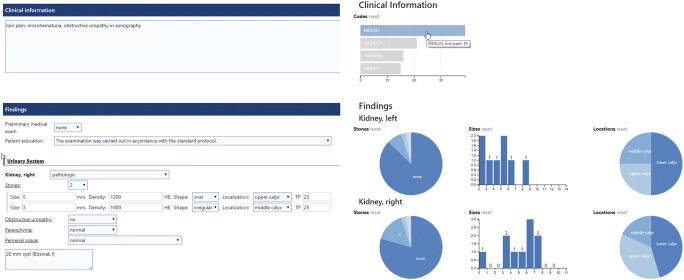

The query of our database regarding the generated codes is possible with standard database tools (SQL, RapidMiner). Figure 5 shows an example of the new possibilities in the analysis of structured data of low-dose CT in patients with suspected urolithiasis. Clinical information as well as free-text fields in the findings and impression sections can be structured and stored in the database.

Fig.5.

Excerpt from a structured report (left) and a dashboard integrated into the MRRE (right) for further analysis (here “low-dose CT of the retroperitoneum”). With hybrid reporting, we are able to analyze structured as well as unstructured information. First, we can use structured data from select fields in the structured reports. Second, by using NLP, we are now able to use initially unstructured data from free-text fields (e.g., clinical information) translated to RadLex® codes. Hybrid reporting provides the basis for in-depth analysis, e.g., the correlation between RadLex-coded clinical information (illustrated in the examples above for urolithiasis) and imaging results.

Discussion

Hybrid reporting is feasible, and we successfully integrated an NLP function into our local MRRT-compliant reporting platform for online analysis. Hybrid reporting enables the analysis of data beneath the structured data in the findings section. Up to now, only select fields and checkboxes themselves as well as their contents can be tagged with RadLex codes®. To our knowledge, we are the first to enable structuring free-text passages by NLP in a reporting platform. Code generation does not lead to a relevant time delay (mean 1.23 s) and can be used for any structured report in our institution.

SR remains a hot topic in radiology [3, 20, 21]. In addition to the numerous advantages of higher report quality and comprehensibility, high-quality training data are required for the development and validation of deep learning algorithms [22]. The Radiological Society of North America provides reporting templates on RadReport to help radiologists deliver high-quality reports [23]. However, structured reports will always contain some free-text passages in the future to allow for some flexibility for radiologists. As far as we know, all report templates that can be downloaded at the RadReport Template Library follow this architecture [23]. Unstructured text fragments cannot be easily retrieved in databases, so our options were to implement structured reports without free-text passages, ignore free text for further analysis, or analyze and structure this information. In several studies, NLP was used to analyze free text in radiological reports, e.g., to categorize oncological response or detect radiologist recommendations for additional imaging of incidental findings [14, 24].

To optimize concept recognition, we plan to develop the feedback function further. Currently, radiologists can add RadLex® codes that NLP did not recognize and correct the modifier (affirmed, speculated, or negated). Providing text fragments and the appropriate code in machine-readable form should automatically facilitate improvement in the NLP engine. In addition, the quality of detection for each of the different concepts (e.g., precision, F1-score) could be displayed for those key users that maintain and support the hybrid reporting tool. These key users can initiate additional training to improve the recognition.

SR focuses on radiologist findings and impressions. Information from clinicians should help the radiologist suggest the correct diagnosis through the clinical history and clear questions from the referring clinician. In our hospital, referring physicians add clinical information by manually filling out a mask in the radiology referral system.

Structuring clinical data is key to linking information from the referring physician with imaging study results. The use of hybrid reporting has the potential to check whether the clinical question of the referring physician was answered by the radiologist. In addition, it enables to test the consistency of the findings and conclusion sections. Hybrid reporting enables the use of decision support by calculating scores (e.g., STONE or CHOKAI score in suspected urolithiasis) or using guideline recommendations for further imaging exams [25, 26]. The prevalence of findings in correlation with clinical symptoms can be of high value for epidemiological research.

To demonstrate the potential of hybrid reporting in radiology, further analyses of structured reports and specific templates have to be conducted to correlate clinical information with radiological findings or to answer specific research questions. To this end, we currently analyze > 1000 structured reports for suspected urolithiasis to correlate clinical information with radiological findings. In addition, we have developed a “minimal structured template” (clinical information, clinical question, findings, and conclusion; each as free-text field) to cover an even broader range of conditions in our MRRE to enable the NLP function. Moreover, studies have to be performed in which the benefits of reporting dashboards for radiologists and clinical referrers will be evaluated.

In some cases, clinical information is quite limited. Folio et al. reported that radiologists find the current clinical history insufficient for effectively selecting and measuring target lesions. Relevant information, such as the primary cancer type or best response date, often were missing in the clinical information from the referrer [8].

The use of speech recognition could potentially improve content from referring clinicians. NLP could automatically structure this information, offering clinical decision support based on it and storing it in a database. Currently, we store structured dose information, the visual impression of the images, and diagnostic confidence in the reporting templates. In addition to these features, more image information could be stored. Radiomics aims to extract high-dimensional quantitative data from clinical images [27]. Combining clinical information and quantitative image features could be a further step towards personalized medicine [28]. The combination of hybrid reporting and multimedia-enhanced radiology reports (or MERR) will provide relevant additional information for structured reports (graphs, key images, tables, calculations) that make the report more helpful for the clinical referrer and for further research [29].

Conclusion

Hybrid reporting combines SR with NLP to code free-text fragments in radiological reports. Our study shows that it is feasible to use hybrid reporting in an MRRT-compliant reporting platform. By using NLP to code the free text used in structured report templates, we can improve the coverage of content in coded form. This further evolution of SR offers numerous opportunities for quality assurance, epidemiological research, providing reporting dashboards with key information for radiologists and clinical referrers, and development of deep learning algorithms. Moreover, our approach enables the possibility to provide decision support, e.g., for consistent recommendations or classifications. This may support the radiologist during reporting. Therefore, this approach could help improve acceptance of SR tools.

Funding Information

This project received funding from the Euratom research and training programme, 2014–2018, under grant agreement No 755523.

Compliance with Ethical Standard

Benedikt Kämpgen is an employee of the Empolis Information Management GmbH (Kaiserslautern, Germany).

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

This retrospective, single-site, controlled cohort study did not need professional legal advice by the Institutional Review Board or informed consent of patients according to the state hospital law. All analyzed patient data were fully de-identified.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brady AP. Radiology reporting-from Hemingway to HAL? Insights Imaging. 2018;9(2):237–46. doi: 10.1007/s13244-018-0596-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee B, Whitehead MT: Radiology Reports: What YOU Think You’re Saying and What THEY Think You’re Saying. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 46(3):186–95, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.European Society of Radiology ESR paper on structured reporting in radiology. Insights Imaging. 2018;9(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s13244-017-0588-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gassenmaier S, Armbruster M, Haasters F, Helfen T, Henzler T, Alibek S, Pförringer D, Sommer WH, Sommer NN. Structured reporting of MRI of the shoulder – improvement of report quality? Eur Radiol. 2017;27(10):4110–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-4778-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoeppe F, Sommer WH, Nörenberg D, Verbeek M, Bogner C, Westphalen CB, Dreyling M, Rummeny EJ, Fingerle AA. Structured reporting adds clinical value in primary CT staging of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(9):3702–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wetterauer C, Winkel DJ, Federer-Gsponer JR, Halla A, Subotic S, Deckart A, Seifert HH, Boll DT, Ebbing J. Structured reporting of prostate magnetic resonance imaging has the potential to improve interdisciplinary communication. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0212444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brook OR, Brook A, Vollmer CM, Kent TS, Sacnhez N, Pedrosa I. Structured Reporting of Multiphasic CT for Pancreatic Cancer: Potential Effect on Staging and Surgical Planning. Radiology. 2015;274:464–72. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folio LR, Nelson CJ, Benjamin M, Ran A, Engelhard G, Bluemke DA. Quantitative Radiology Reporting in Oncology: Survey of Oncologists and Radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(3):W233–43. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.14054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobez LM, Kim SH, Angstwurm M, Stormann S, Pforringer D, Schmidutz F, Prezzi D, Kelly-Morland C, Sommer WH, Sabel B, Nörenberg D: Creating high-quality radiology reports in foreign languages through multilingual structured reporting. Eur Radiol 10.1007/s00330-019-06206-8. 2019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Pinto Dos Santos D, Scheibl S, Arnhold G, Maehringer-Kunz A, Düber C, Mildenberger P, Kloeckner R: A proof of concept for epidemiological research using structured reporting with pulmonary embolism as a use case. Br J Radiol doi 10.1259/bjr.20170564. 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.IHE Radiology Technical Committee: Management of Radiology Report Templates (MRRT) Rev.1.7 - Trial Implementation, July 27, 2018. Available at https://www.ihe.net/uploadedFiles/Documents/Radiology/IHE_RAD_Suppl_MRRT.pdf. Accessed 1 April 2020

- 12.Pinto Dos Santos D, Klos G, Kloeckner R, Oberle R, Dueber C, Mildenberger P. Development of an IHE MRRT-compliant open-source web-based reporting platform. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(1):424–30. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jungmann F, Kuhn S, Kampgen B. Basics and applications of Natural Language Processing (NLP) in radiology. Radiologe. 2018;58(8):764–8. doi: 10.1007/s00117-018-0426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dutta S, Long WJ, Brown DF, Reisner AT. Automated detection using natural language processing of radiologists recommendations for additional imaging of incidental findings. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):162–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huesch MD, Cherian R, Labib S, Mahraj R. Evaluating Report Text Variation and Informativeness: Natural Language Processing of CT Chest Imaging for Pulmonary Embolism. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(3):554–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galvez JA, Pappas JM, Ahumada L, Martin JN, Simpao AF, Rehman MA, Witmer C. The use of natural language processing on pediatric diagnostic radiology reports in the electronic health record to identify deep venous thrombosis in children. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;44(3):281–90. doi: 10.1007/s11239-017-1532-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langlotz CP. RadLex: a new method for indexing online educational materials. Radiographics. 2006;26(6):1595–7. doi: 10.1148/rg.266065168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jungmann F, Kuhn S, Tsaur I, Kampgen B: Natural language processing in radiology: Neither trivial nor impossible. Radiologe 59(9):828–32, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Pinto dos Santos D, Arnhold G, Mildenberger P, Düber C, Kloeckner R: Guidelines Regarding §16 of the German Transplantation Act - Initial Experiences with Structured Reporting. Rofo 189:1145–51, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Pinto Dos Santos D, Baessler B. Big data, artificial intelligence, and structured reporting. Eur Radiol Exp. 2018;2(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s41747-018-0071-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinto Dos Santos D, Hempel JM, Mildenberger P, Klockner R, Persigehl T. Structured Reporting in Clinical Routine. Rofo. 2019;191(1):33–9. doi: 10.1055/a-0636-3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinto dos Santos D, Brodehl S, Baeßler B, Arnhold G, Dratsch T, Chon SH et al.: Structured report data can be used to develop deep learning algorithms: a proof of concept in ankle radiographs. Insights Imaging 10(1):93, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Radiological Society of North America: RadReport Template Library. Available at https://radreport.org. Accessed 1 April 2020

- 24.Chen PH, Zafar H, Galperin-Aizenberg M, Cook T. Integrating Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning Algorithms to Categorize Oncologic Response in Radiology Reports. J Digit Imaging. 2018;31(2):178–84. doi: 10.1007/s10278-017-0027-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukuhara H, Ichiyanagi O, Midorikawa S, Kakizaki H, Kaneko H, Tsuchiya N. Internal validation of a scoring system to evaluate the probability of ureteral stones: The CHOKAI score. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(12):1859–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang RC, Rodriguez RM, Moghadassi M, Noble V, Bailitz J, Mallin M, Corbo J, Kang TL, Chu P, Shiboski S, Smith-Bindman R. External Validation of the STONE Score, a Clinical Prediction Rule for Ureteral Stone: An Observational Multi-institutional Study. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(4):423–32 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rizzo S, Botta F, Raimondi S, Origgi D, Fanciullo C, Morganti AG, Bellomi M. Radiomics: the facts and the challenges of image analysis. Eur Radiol Exp. 2018;2(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s41747-018-0068-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambin P, Leijenaar RTH, Deist TM, Peerlings J, de Jong EEC, van Timmeren J, Sanduleanu RTHM, Even AJG, Jochems A, van Wijk Y, Woodruff H, van Soest J, Lustberg T, Roelofs E, van Elmpt W, Dekker A, Mottaghy FM, Wildberger JE, Walsh S. Radiomics: the bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(12):749–62. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folio LR, Machado LB, Dwyer AJ. Multimedia-enhanced Radiology Reports: Concept, Components, and Challenges. Radiographics. 2018;38(2):462–82. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017170047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]