Abstract

Objective: This study investigated survival in selected Chinese patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma who received initial chemotherapy with pemetrexed. We also explored the relationship between genetic biomarkers and pemetrexed efficacy.

Methods: We retrospectively collected patients (n = 1,047) enrolled in the Chinese Patient Assistance Program from multiple centers who received pemetrexed alone or combined with platinum as initial chemotherapy and continued pemetrexed maintenance therapy for advanced lung adenocarcinoma from November 2014 to June 2017. The outcomes were duration of treatment (DOT) and overall survival (OS). Clinical features were analyzed for their influence on the treatment effect and prognosis. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed to identify genetic biomarkers associated with the efficacy of pemetrexed.

Results: The median DOT was 9.1 months (95% CI: 8.5–9.8), and the median OS was 26.2 months (95% CI: 24.2–28.1). OS was positively correlated with DOT (r = 0.403, P < 0.001). Multivariable analysis showed that smoking status and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) were independently associated with DOT; smoking status, ECOG PS, targeted therapy, and EGFR/ALK/ROS1 status were independently associated with OS. NGS in 22 patients with available samples showed genes with high mutation rates were: TP53 (54.5%), EGFR (50.0%), MYC (18.2%), and PIK3CA (13.6%). When grouped based on progression-free survival (PFS) reported in the PARAMOUNT study, the DOT > 6.9 months set was associated with PIK3CA, ALK, BRINP3, CDKN2A, CSMD3, EPHA3, KRAS, and RB1 mutations, while ERBB2 mutation was observed only in the DOT ≤ 6.9 months set.

Conclusion: This study shows that initial chemotherapy with pemetrexed is an effective regimen for advanced lung adenocarcinoma in selected Chinese patients. There is no specific genetic profile predicting the benefit of pemetrexed found by NGS. Biomarkers predicting the efficacy of pemetrexed need further exploration.

Keywords: pemetrexed, lung adenocarcinoma, Chinese, next-generation sequencing, chemotherapy

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death all over the world (1). About 80–85% of human lung cancers belong to the category of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). These patients usually present with locally advanced (stage IIIB) or metastatic disease (stage IV) (2). Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy have become a standard first-line treatment for patients with no oncogenic driver alterations in advanced NSCLC. Nevertheless, which chemotherapy regimen combined with immunotherapy agents, will achieve optimal outcomes for these patients is unknown. In addition, in developing countries, including China, immunotherapy is often too expensive for many patients, although these drugs are recommended by the available guidelines (3). Therefore, chemotherapy is still indispensable (4–6). Some randomized controlled trials and real-world studies abroad demonstrated that pemetrexed-cisplatin induction and pemetrexed maintenance therapy is an effective and well-tolerated regimen in stage IIIB-IV patients with non-squamous NSCLC (7–14), but there is still a lack of large sample size evidence to report the survival benefit of pemetrexed as the initial chemotherapy in Chinese patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma.

Moreover, heterogeneity in response to pemetrexed has been observed, some patients experience long progression-free survival (PFS) or overall survival (OS), whereas others are having short PFS and OS (15). Identifying patients who are unlikely to benefit from pemetrexed would avoid unnecessary treatment and allow alternative therapy that might achieve better outcomes. Although we know that histologically non-squamous NSCLC is a predictive factor for the efficacy of pemetrexed, this still cannot help us screen out the patients who will really benefit from pemetrexed (16). Previous studies showed that thymidylate synthase (TS), folate receptor alpha (FRA), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene mutation, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangement, and plasma microRNA levels might be predictive markers for pemetrexed (17–22), but the predictability of these biomarkers has not been reproducible due to the lack of prospective studies. Therefore, it is necessary to explore novel and reliable biomarkers to predict the effect of pemetrexed.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) based on tumor tissue or liquid biopsy has begun to play a role in genomic profiling. Its high-throughput nature makes testing of thousands of genes or even the whole genomes possible with a small amount of DNA, allowing this method to identify actionable genomic alterations (23).

In order to reduce the financial burden and provide timely treatment for Chinese patients, the Chinese Primary Health Care Foundation launched a patient assistance program (PAP) for advanced non-squamous NSCLC patients with pemetrexed as maintenance therapy; those patients receive a 100% discount after a self-funded four-cycle induction pemetrexed therapy, starting from October 1, 2014. The patients who do not complete the four-cycle induction pemetrexed therapy are not eligible for the PAP. Following the implementation of the PAP, we observed the duration of treatment (DOT) with pemetrexed and OS among these selected patients and compared the genomic differences between the patients with long and short duration of pemetrexed treatment to explore potential predictive biomarkers.

Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective study of data from multiple centers across China. The patients were funded by the PAP to receive pemetrexed and visited their treating hospitals from November 2014 to June 2017. The PAP is offered by the Chinese Primary Health Care Foundation. All data were extracted from the patients' medical records, and telephone follow-up was conducted by physicians across more than 200 tertiary hospitals in China. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital, Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences, School of Medicine, South China University of Technology (No. GDREC2017303H). This study was conducted in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) principles. Written informed consent was obtained from all included patients.

Study Population

The patients meeting the following criteria were included: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0–2; lung adenocarcinoma; stage IV (according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system, 7th edition); pemetrexed as initial chemotherapy; received four cycles of pemetrexed monotherapy or pemetrexed plus platinum as induction chemotherapy with no disease progression according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), version 1.1 (24): complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD); and at least one cycle of pemetrexed maintenance therapy from PAP.

The exclusion criteria were: history of chemotherapy; combination with other antitumor drugs such as bevacizumab; disease progression before the completion of four cycles of induction pemetrexed chemotherapy; or unavailable treatment information or survival data.

Data Source

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were extracted from their medical records and entered into the Medical Record Abstraction Form (MERAF) by designated hospital staff. These characteristics included sex, age, smoking status, disease stage at diagnosis, the time at diagnosis, disease stage at pemetrexed treatment, NSCLC histological type, gene status, ECOG PS, the time of pemetrexed treatment initiation, first-line anticancer treatment regimen, cycles, the best response to pemetrexed treatment, the time of progressive disease administered with pemetrexed, other treatment after pemetrexed, survival status, and the time to death. Patients who had smoked ≥100 cigarettes in their lifetime were defined as smokers (25). The last time of pemetrexed treatment was obtained through the electronic PAP system. Survival data were collected by the follow-up registration system from each site and by telephone follow-up. The response was assessed based on imaging examination reports and medical case notes.

Outcomes

The outcomes were the DOT of pemetrexed and OS. DOT was defined as the time from the initiation to the last pemetrexed chemotherapy. OS was defined as the time from the initiation of pemetrexed chemotherapy to death or the last follow-up, whichever came first. The last follow-up was conducted on March 31, 2018.

Grouping

The median PFS was 6.9 months for patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC who received maintenance therapy with pemetrexed after induction chemotherapy with pemetrexed plus cisplatin according to the double-blind, phase 3, randomized controlled trial “PARAMOUNT” (9). Since the PARAMOUNT study provided high-level evidence for maintenance therapy with pemetrexed, we selected their median PFS as the cutoff for grouping. In the present study, according to their PFS, patients with NGS detection whose DOT was ≤ 6.9 months were assigned to the short duration group, whereas the long duration group included patients with DOT of >6.9 months.

Next-Generation Sequencing

Patients with available blood samples at Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital underwent NGS. Plasma samples were obtained after disease progression in patients with initial pemetrexed chemotherapy. The NGS tests targeted at least 139 genes related to lung cancer and were performed in two clinical testing centers (Burning Rock Biotech Ltd and Nanjing Geneseeq Technology Inc.). First, DNA was extracted from blood. Then, the NGS library was prepared, and DNA was profiled using a capture-based sequencing panel. Finally, sequence data were analyzed and compared between the long and short duration groups.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the enrolled patients. DOT and OS were assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method. We also performed the Pearson correlation test to evaluate the correlation between DOT and OS. The factors associated with DOT and OS were analyzed by performing univariable and multivariable analyses using Cox proportional hazards models, including the following covariables: age, sex, smoking status, ECOG PS, and gene status. Multivariable analysis of OS also included the factor: targeted therapy. Variables with P < 0.1 in the univariable analyses were included in the multivariable analysis. Two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

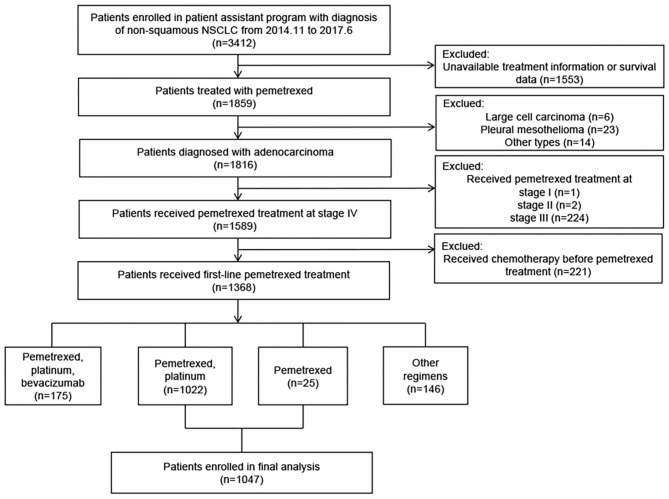

A total of 3,412 patients were screened. Of these, 1,047 patients from 44 hospitals with advanced lung adenocarcinoma who received pemetrexed treatment were included in the analyses. The screening flowchart and clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Figure 1, Table 1, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients' screening for inclusion in the study.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma.

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 1,047) |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 594 (56.7%) |

| Female | 453 (43.3%) |

| Age (years) | |

| Median (range) | 59 (24–93) |

| <65, n (%) | 758 (72.4%) |

| ≥65, n (%) | 289 (27.6%) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Non-smoker | 608 (58.1%) |

| Smoker | 439 (41.9%) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |

| 0–1 | 984 (94.0%) |

| 2 | 63 (6.0%) |

| Targeted therapy before pemetrexed treatment, n (%) | |

| Yes | 149 (14.2%) |

| No | 898 (84.8%) |

| Gene status before pemetrexed treatment, n (%) | |

| EGFR Mutation | |

| Positive | 266 (25.4%) |

| Negative | 568 (54.3%) |

| Unknown | 213 (20.3%) |

| ALK Rearrangement | |

| Positive | 59 (5.6%) |

| Negative | 580 (55.4%) |

| Unknown | 408 (39.0%) |

| KRAS Mutation | |

| Positive | 11 (1.1%) |

| Negative | 147 (14.0%) |

| Unknown | 889 (84.9%) |

| ROS1 Fusion | |

| Positive | 18 (1.7%) |

| Negative | 233 (22.3%) |

| Unknown | 796 (76.0%) |

| Chemotherapy regimen, n (%) | |

| Pemetrexed plus platinum | 1,022 (97.6%) |

| Pemetrexed monotherapy | 25 (2.4%) |

| Best tumor response, n (%) | |

| PR | 477 (45.6%) |

| SD | 570 (54.4%) |

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

The gene status before pemetrexed treatment was analyzed, including EGFR, ALK, Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), and c-ros oncogene 1 (ROS1). The gene aberration rates in patients with definitive results were 31.9% (266/834) for EGFR mutation, 9.2% (59/639) for ALK rearrangement, 7.0% (11/158) for KRAS mutation, and 7.2% (18/251) for ROS1 fusion (Table 2).

Table 2.

The gene aberration rates in patients with definitive results.

| Gene aberration | Positive, n | Negative, n | Mutation rate, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | 266 | 568 | 31.9% |

| ALK | 59 | 580 | 9.2% |

| ROS1 | 18 | 233 | 7.2% |

| KRAS | 11 | 147 | 7.0% |

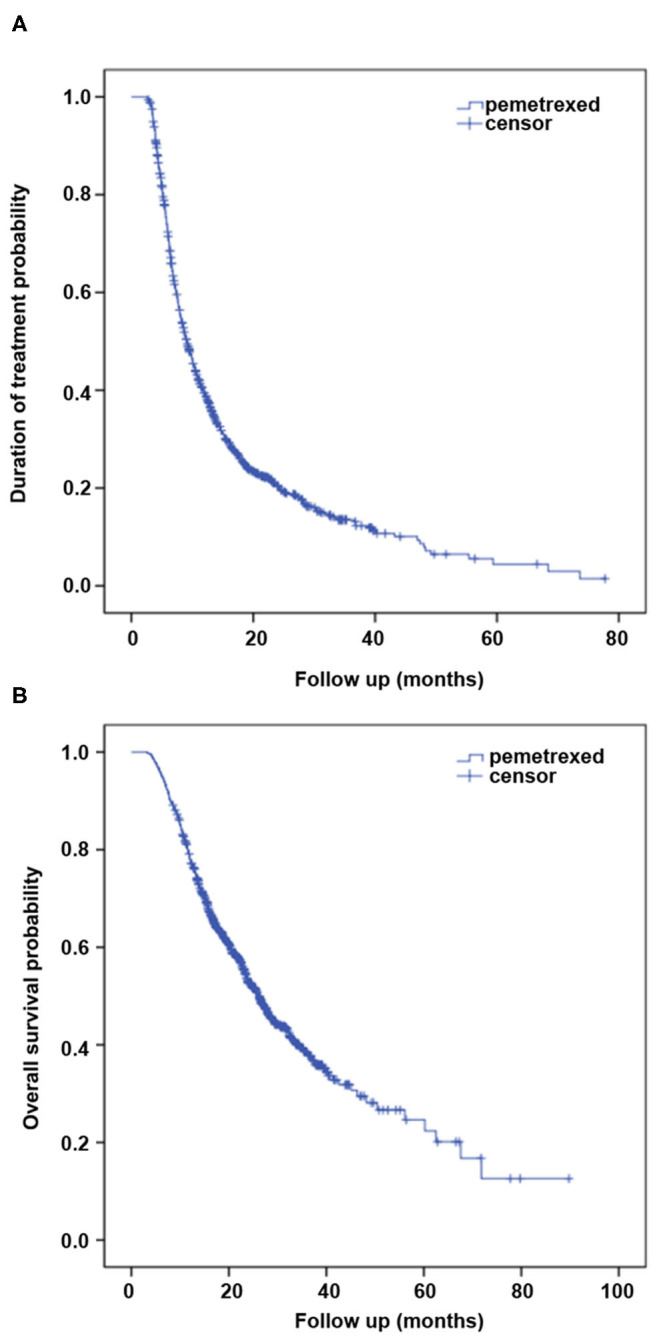

Survival Outcomes

The median follow-up of all patients was 19.1 months. The median DOT was 9.1 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 8.5–9.8) for 811 patients who had stopped pemetrexed treatment at the last follow-up (Figure 2A). Among the 536 patients who had died, the median OS was 26.2 months (95%CI: 24.2–28.1) (Figure 2B). Moreover, a positive correlation was observed between DOT defined in the present study and OS evaluated by Pearson correlation test (r = 0.543, P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of (A) duration of treatment (DOT) and (B) overall survival (OS) for 1,047 patients treated with pemetrexed.

DOT and OS were both longer than the PFS and OS observed in the PARAMOUNT, JMII, and S110 trials. Clinical characteristics and efficacy of pemetrexed in the present study were compared with these trials (Supplemental Table 1).

Factors Associated With Duration of Treatment and Overall Survival

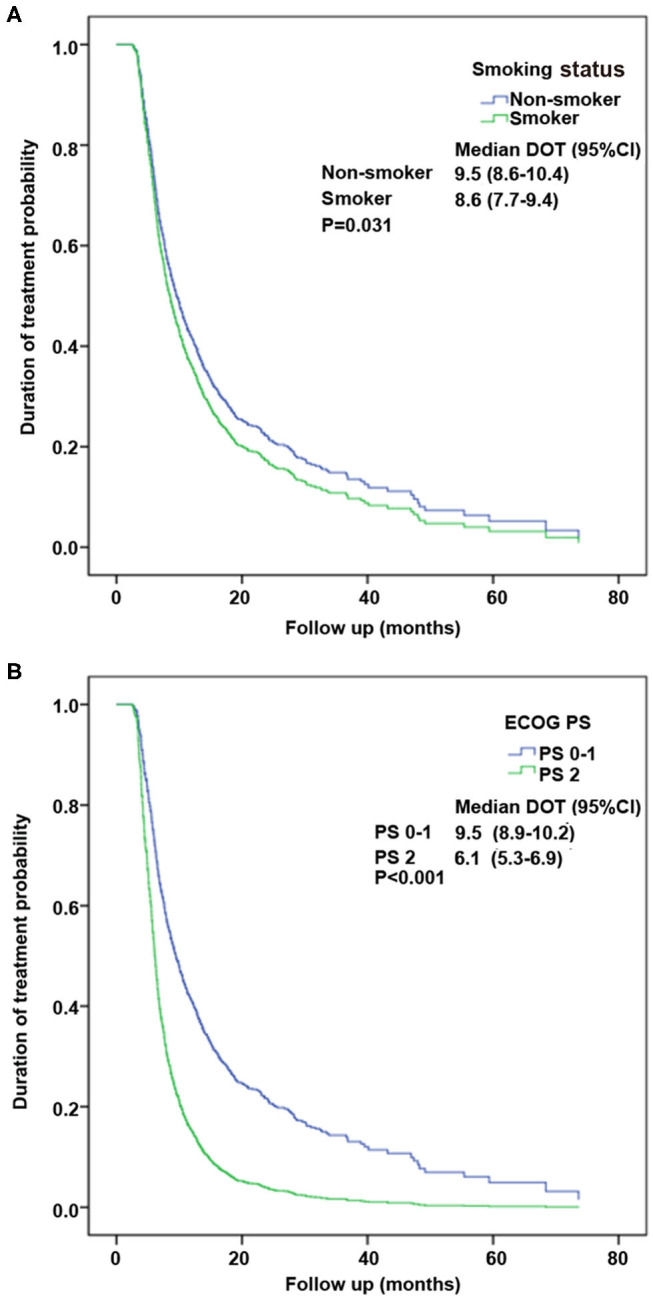

When the variables were analyzed by univariable analysis, sex, smoking status, ECOG PS, and gene status (ALK, KRAS, ROS1) were revealed as significant factors (P < 0.1) associated with DOT. These parameters were included in the multivariable Cox regression analysis. As a result, only smoking status (hazard ratio [HR], 1.167; 95%CI, 1.015–1.342; P = 0.031) and ECOG PS (HR, 2.112; 95% CI, 1.631–2.735; P < 0.001) were independent factors influencing DOT of pemetrexed (Table 3). Kaplan–Meier curves of DOT about smoking status and ECOG PS factors are shown in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of duration of pemetrexed treatment.

| Variable | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age (≥65 vs. <65 years) | 1.045 | 0.896 | 1.219 | 0.574 | - | - | - | - |

| Sex (female vs. male) | 0.889 | 0.772 | 1.022 | 0.099 | - | - | - | 0.642 |

| Smoking status (smoker vs. non-smoker) | 1.163 | 1.011 | 1.338 | 0.034 | 1.167 | 1.015 | 1.342 | 0.031 |

| ECOG PS (2 vs. 0–1) | 2.105 | 1.626 | 2.726 | <0.001 | 2.112 | 1.631 | 2.735 | <0.001 |

| EGFR Mutation | ||||||||

| (+ vs. -) | 1.071 | 0.909 | 1.261 | 0.413 | - | - | - | - |

| (unknown vs. -) | 0.976 | 0.814 | 1.171 | 0.795 | - | - | - | - |

| ALK Rearrangement | ||||||||

| (+ vs. -) | 0.716 | 0.520 | 0.987 | 0.041 | - | - | - | 0.056 |

| (unknown vs. -) | 1.000 | 0.866 | 1.155 | 0.996 | - | - | - | 0.943 |

| KRAS Mutation | ||||||||

| (+ vs. -) | 1.754 | 0.919 | 3.348 | 0.088 | - | - | - | 0.117 |

| (unknown vs. -) | 1.069 | 0.878 | 1.301 | 0.509 | - | - | - | 0.788 |

| ROS1 Fusion | ||||||||

| (+ vs. -) | 0.604 | 0.343 | 1.063 | 0.080 | - | - | - | 0.096 |

| (unknown vs. -) | 1.010 | 0.855 | 1.192 | 0.911 | - | - | - | 0.762 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves of the duration of treatment (DOT) about the significant factors by multivariate analysis. (A) Performance status (PS) factor. (B) Smoking status factor.

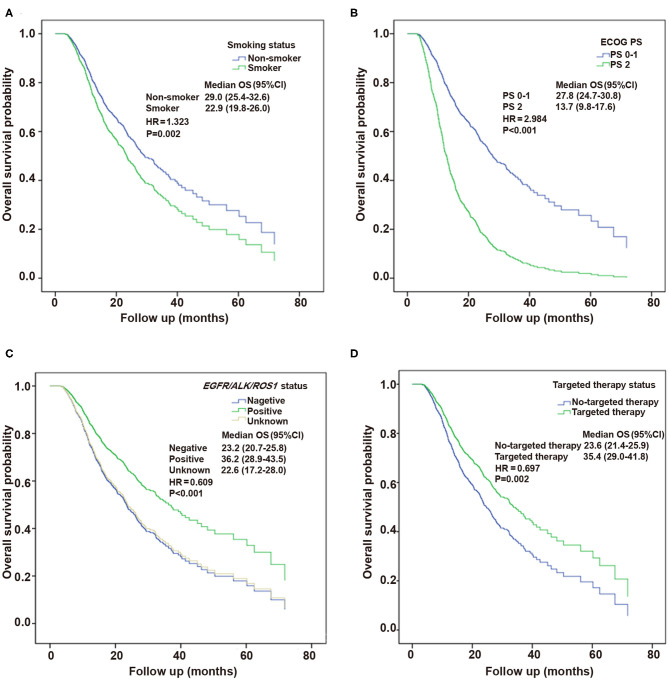

Multivariable analysis in the Cox proportional hazards model revealed the independent factors influencing OS, including smoking status (HR, 1.323; 95% CI, 1.111–1.574; P = 0.002), ECOG PS (HR, 2.984; 95% CI, 2.286–3.894; P < 0.001), targeted therapy (HR, 0.697; 95% CI, 0.556–0.875; P = 0.002), and EGFR/ALK/ROS1 status (HR, 0.609; 95% CI, 0.552–0.863; P < 0.001) (Table 4). Figure 4 presents the Kaplan–Meier curves of OS about these significant factors: smoking status, ECOG PS, EGFR/ALK/ROS1, and targeted therapy factors.

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of overall survival.

| Variable | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age (≥65 vs. <65 years) | 1.242 | 1.031 | 1.495 | 0.022 | - | - | - | 0.093 |

| Sex (female vs. male) | 0.731 | 0.614 | 0.870 | <0.001 | - | - | - | 0.267 |

| Smoking status (smoker vs. non-smoker) | 1.416 | 1.194 | 1.680 | <0.001 | 1.323 | 1.111 | 1.574 | 0.002 |

| ECOG PS (2 vs. 0–1) | 2.934 | 2.254 | 3.821 | <0.001 | 2.984 | 2.286 | 3.894 | <0.001 |

| EGFR/ALK/ROS1 Status | ||||||||

| (+ vs. -) | 0.569 | 0.463 | 0.699 | <0.001 | 0.609 | 0.552 | 0.863 | <0.001 |

| (unknown vs. -) | 1.023 | 0.822 | 1.274 | 0.838 | 0.979 | 0.785 | 1.221 | 0.852 |

| Targeted therapy (with vs. without) | 0.599 | 0.485 | 0.740 | <0.001 | 0.697 | 0.556 | 0.875 | 0.002 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival (OS) about the significant factors by multivariate analysis. (A) Smoking status factor. (B) Performance status (PS) factor. (C) EGFR/ALK/ROS1 mutation factor. (D) Targeted therapy factor.

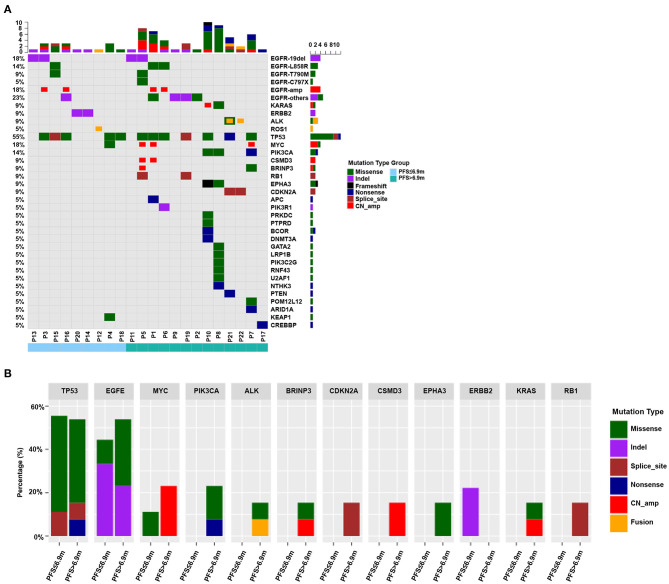

Genetic Differences Between the Long and Short Duration Groups Using on Next-Generation Sequencing

Among 1,047 patients, 117 patients received initial chemotherapy with pemetrexed at Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital. Twenty-two plasma samples from 22 patients were collected to perform NGS. Their DOT ranged from 4.5 to 27.1 months. Thirteen patients were assigned to the long duration group (DOT > 6.9 months), whereas the short duration group (DOT ≤ 6.9 months) included nine patients. Their clinical characteristics are presented in Supplemental Table 2. The demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients were similar between the two groups in regard to age, sex, smoking status, and best response.

A total of 30 intersection genes were analyzed in these 22 patients, and the genes with high mutation rate included TP53, EGFR, MYC, and PIK3CA, accounting for 54.5% (12/22), 50.0% (11/22), 18.2% (4/22), and 13.6% (3/22), respectively (Figure 5A). We also compared the difference of 12 genes that were mutated in more than one patient between the two groups (Figure 5B). Three genes (TP53, EGFR, and MYC) appeared recurrently in the two groups. Genes that were mutated in the long duration group but not in the short duration group included PIK3CA, ALK, BRINP3, CDKN2A, CSMD3, EPHA3, KRAS, and RB1. ERBB2 mutation was detected only in the short duration group.

Figure 5.

(A) Mutational frequency of 30 intersection genes analyzed in 22 patients by next-generation sequencing (NGS). The genes with high mutation rate included TP53, EGFR, MYC, and PIK3CA. (B) The differences of 12 genes mutational frequency between PFS > 6.9 months and PFS ≤ 6.9 months groups. TP53, EGFR, and MYC appeared recurrently in the two groups. PIK3CA, ALK, BRINP3, CDKN2A, CSMD3, EPHA3, KRAS, and RB1 occurred only in the PFS > 6.9 months group whereas ERBB2 mutation was detected only in the PFS ≤ 6.9 months group.

Discussion

Previous randomized controlled trials demonstrated that pemetrexed is effective and well-tolerated for patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC (9–11). The PARAMOUNT trial was a relatively large randomized controlled trial that investigated whether continuation maintenance therapy with pemetrexed improved PFS after induction therapy with pemetrexed plus cisplatin in 539 patients randomly assigned to receive continuation maintenance therapy with pemetrexed plus best supportive care (n = 359) or with placebo plus best supportive care (n = 180) (9). The median PFS of pemetrexed during the induction plus maintenance period was 6.9 months, and the OS was 16.9 months. Therefore, that study provides high-level evidence for maintenance therapy with pemetrexed. Nevertheless, 94% of the patients enrolled in the PARAMOUNT study were Caucasian. Yang et al. reviewed the JMII and S110 studies to supplement the efficacy and safety data from PARAMOUNT on pemetrexed maintenance therapy in East Asian patients with non-squamous NSCLC (26). The median PFS during the entire period (induction plus maintenance) in the JMII and S110 studies was 5.7 months (95% CI, 4.4–7.3 months) and 6.83 months (95% CI, 5.78–7.98 months), which was consistent with that observed in the PARAMOUNT study (26). The median OS during the entire period was 20.2 months (95% CI, 16.7 to not available) in the JMII trial, whereas, in the S110 trial, the median OS could not be estimated due to a high censor rate (72.9%). Although the two studies suggested the efficacy of pemetrexed induction and maintenance therapy in East Asian patients, their samples were small. In our study, we collected a total of 1,047 patients from PAP throughout China, including 44 tertiary hospitals. It is the largest study performed so far to investigate the efficacy of pemetrexed initial chemotherapy in Chinese patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma. The results showed that the median DOT of pemetrexed induction plus maintenance therapy was 9.1 months (95% CI: 8.5–9.8), and the median OS was 26.2 months (95% CI: 24.2–28.1), which were longer than that observed in clinical trials above. It added some evidence based on large samples showing that patients with lung adenocarcinoma can benefit from pemetrexed initial chemotherapy, especially for East Asians. This also provides a basis for which chemotherapy regimen may be the most appropriate combination with immunity inhibitors such as PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor in the age of immunotherapy.

In the present study, the DOT was longer than the PFS observed in the PARAMOUNT, JMII, and S110 trials. One reason may be that our outcome DOT is different from PFS and is defined as the time from the start to the last treatment of pemetrexed. In clinical trials, the PFS is a common endpoint. Patients in clinical trials stop pemetrexed treatment once evaluated to have disease progression, according to RECIST. Nevertheless, in routine clinical practice, some patients still have a high likelihood of responding to maintenance therapy despite RECIST suggesting disease progression. Indeed, EGFR mutated patients with gradual and local progression after EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) treatment failure still show persistent symptom benefit to continuing EGFR-TKIs treatment (27). In clinical practice, there are also some patients who receive pemetrexed treatment with gradual and local progression and showing persistent clinical benefit, although the disease was evaluated as progression according to RECIST. Although more details regarding the PFS and treatment beyond progression were not available, the DOT of 9.1 months in the present study was consistent with the PFS of 9.4 months reported by a real-world study from USA (12). Moreover, because of toxicity or other reasons, some patients may quit pemetrexed treatment when their tumors had not enlarged. Therefore, DOT may reflect the efficacy and safety of pemetrexed treatment more practically and objectively in clinical practice. The other reason may be that the present study was conducted in selected Chinese patients who might have a good prognosis and good response to pemetrexed since they completed the four-cycle induction therapy.

OS was also longer in the present study than that observed in the PARAMOUNT and JMII trials. Selected Chinese patients who received at least four cycles of pemetrexed treatment were enrolled in our study, which resulted in the longer OS besides the DOT. We also compared the clinical characteristics in the present study with those of the PARAMOUNT and JMII trials. Race and druggable target gene mutations were different between this study and the PARAMOUNT trial. Our study focused on Chinese patients, while 94% of patients were Caucasian in the PARAMOUNT trial, and we know that there are differences in genetic profile between the two races (28). EGFR mutations are more common in Asian populations than Caucasians (29). The rate of EGFR mutation in the present study is lower than that reported by Wu et al. (30) due to diverse gene detection methods with different sensitivity from 44 tertiary hospitals throughout China and certain percentages of patients with unknown EGFR status. Even so, EGFR mutated rate in our study was different from the PARAMOUNT trial. The multivariable analysis also showed that the EGFR/ALK/ROS1 status and targeted therapy were independently associated with OS. This was similar to a previous study which reported that patients with an oncogenic driver mutation and who received a targeted therapy had survival benefits compared with those without oncogenic mutation or those who did not receive targeted therapy (31). The JMII trial was performed to evaluate the efficacy of pemetrexed and carboplatin, followed by pemetrexed maintenance therapy in chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC in Japan. Out of 109 patients, 106 were evaluable for efficacy analysis. Although the median OS was 20.2 months (95% CI, 16.7 to not available), among 60 patients who received continuation maintenance with pemetrexed, the median OS from the beginning of induction treatment was not calculable. Besides genetic differences, more effective anticancer agents such as immunotherapy after pemetrexed treatment failure have been available from 2014 to 2018 when our study was conducted (32). The PARAMOUNT trial was carried out between 2008 and 2010, and the OS data cutoff date was in 2012 when antitumor treatment was more limited. The JMII trial was carried out between 2009 and 2010. All of these situations are potential reasons why the OS in our study was longer than that of previous clinical trials.

The multivariable analysis showed that the smoking status and ECOG PS were independently associated with DOT and OS, which was consistent with some previous studies (33–35). These factors might be potential clinical predictors for the effect of pemetrexed. Nevertheless, the differences of pemetrexed response among the patients could not be completely predicted by these clinical factors. This study tried to find potential genetic factors using NGS. A heterogeneous genetic profile was observed between the two groups by NGS. Mutations in PIK3CA, ALK, BRINP3, CDKN2A, CSMD3, EPHA3, KRAS, and RB1 were only observed in the long duration group, whereas ERBB2 mutation was only observed in the short duration group. But, these genes were not specific genetic profile benefit to pemetrexed treatment and may not predict the efficacy of pemetrexed. Further studies are needed to explore the predictor of the benefit to pemetrexed treatment in the future.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the present study excluded the patients who received pemetrexed for <4 cycles due to disease progression. This cannot represent the whole pemetrexed-treated patients in clinical practice in a real-world condition. Second, there are certain percentages of patients with unknown EGFR, ALK, and ROS1 statuses, and the rate of patients with druggable target gene mutations received targeted therapy before pemetrexed treatment is low. Moreover, the exploration and comparison of gene profiles by NGS were conducted in a small sample of patients. All of these might make a bias to the conclusion. Third, more details regarding the PFS and treatment during beyond progression were not collected to prove the effectiveness of continuing pemetrexed chemotherapy beyond progression according to RECIST criteria. PFS and treatment beyond progression will have to be examined.

Conclusion

This study shows that initial chemotherapy with pemetrexed is an effective regimen for advanced lung adenocarcinoma in selected Chinese patients. There is no specific genetic profile predicting the benefit of pemetrexed found by NGS. Biomarkers predicting the efficacy of pemetrexed need further exploration. More studies are needed to find a clinical treatment strategy of that chemotherapy combines with immunotherapy or targeted therapy.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: The National Omics Data Encyclopedia (http://www.biosino.org/node/project/detail/OEP001054) and the European Genome-phenome Archive (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega/studies/EGAS00001004546).

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital, Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences, School of Medicine, South China University of Technology. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

QZ and Y-LW conceived the idea and designed the experiments. L-HG and M-FZ analyzed the data together. L-HG wrote the manuscript. All authors, except QZ and Y-LW, were involved in the acquisition of data. All authors participated in the interpretation of the study results, drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the study participants. The authors also thank to Hong-Hong Yan who helped making statistic analysis and two next-generation sequencing (NGS) testing centers (Burning Rock Biotech Ltd and Nanjing Geneseeq Technology Inc.) uploading the data to online database. This study was supported by the Chinese Primary Health Care Foundation that has launched a PAP for advanced non-squamous NSCLC patients with initial pemetrexed treatment.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (grant no. 2016YFC1303800 to QZ), National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81871891 to QZ), and High-level Hospital Construction Project (grant no. DFJH201810 to QZ).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.01568/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2018) 68:394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blandin Knight S, Crosbie PA, Balata H, Chudziak J, Hussell T, Dive C. Progress and prospects of early detection in lung cancer. Open Biol. (2017) 7:170070. 10.1098/rsob.170070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Version 4.2020. Fort Washington: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi G, Alama A, Genova C, Rijavec E, Tagliamento M, Biello F, et al. The evolving role of pemetrexed disodium for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. (2018) 19:1969–76. 10.1080/14656566.2018.1536746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stinchcombe TE, Borghaei H, Barker SS, Treat JA, Obasaju C. Pemetrexed with platinum combination as a backbone for targeted therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. (2016) 17:1–9. 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Q, Song Y, Zhang X, Chen GY, Zhong DS, Yu Z, et al. A multicenter survey of first-line treatment patterns and gene aberration test status of patients with unresectable Stage IIIB/IV nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer in China (CTONG 1506). BMC Cancer. (2017) 17:462. 10.1186/s12885-017-3451-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2008) 26:3543–51. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park CK, Oh IJ, Kim KS, Choi YD, Jang TW, Kim YS, et al. Randomized phase III study of docetaxel plus cisplatin versus pemetrexed plus cisplatin as first-line treatment of nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: a TRAIL trial. Clin Lung Cancer. (2017) 18:e289–96. 10.1016/j.cllc.2017.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paz-Ares L, de Marinis F, Dediu M, Thomas M, Pujol JL, Bidoli P, et al. Maintenance therapy with pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care after induction therapy with pemetrexed plus cisplatin for advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (PARAMOUNT): a double-blind, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. (2012) 13:247–55. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70063-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu YL, Lu S, Cheng Y, Zhou C, Wang M, Qin S, et al. Efficacy and safety of pemetrexed/cisplatin versus gemcitabine/cisplatin as first-line treatment in Chinese patients with advanced nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. (2014) 85:401–7. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paz-Ares LG, de Marinis F, Dediu M, Thomas M, Pujol JL, Bidoli P, et al. PARAMOUNT: final overall survival results of the phase III study of maintenance pemetrexed versus placebo immediately after induction treatment with pemetrexed plus cisplatin for advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2013) 31:2895–902. 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winfree KB, Torres AZ, Zhu YE, Muehlenbein C, Aggarwal H, Woods S, et al. Treatment patterns, duration and outcomes of pemetrexed maintenance therapy in patients with advanced NSCLC in a real-world setting. Curr Med Res Opin. (2019) 35:817–27. 10.1080/03007995.2018.1547273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moro-Sibilot D, Smit E, de Castro Carpeno J, Lesniewski-Kmak K, Aerts J, Villatoro R, et al. Outcomes and resource use of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients treated with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy across Europe: FRAME prospective observational study. Lung Cancer. (2015) 88:215–22. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, San Antonio B, Yan Y, Chen J, Goodloe RJ, John WJ. Safety profiles of non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with pemetrexed plus carboplatin: a real-world retrospective, observational, cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. (2017) 33:931–36. 10.1080/03007995.2017.1297700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park S, Kim HJ, Choi CM, Lee DH, Kim SW, Lee JS, et al. Predictive factors for a long-term response duration in non-squamous cell lung cancer patients treated with pemetrexed. BMC Cancer. (2016) 16:417. 10.1186/s12885-016-2457-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scagliotti G, Hanna N, Fossella F, Sugarman K, Blatter J, Peterson P, et al. The differential efficacy of pemetrexed according to NSCLC histology: a review of two Phase III studies. Oncologist. (2009) 14:253–63. 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimizu T, Nakanishi Y, Nakagawa Y, Tsujino I, Takahashi N, Nemoto N, et al. Association between expression of thymidylate synthase, dihydrofolate reductase, and glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase and efficacy of pemetrexed in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. (2012) 32:4589–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi H, Guo J, Li C, Wang Z. A current review of folate receptor alpha as a potential tumor target in non-small-cell lung cancer. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2015) 9:4989–96. 10.2147/DDDT.S90670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun JM, Ahn JS, Jung SH, Sun J, Ha SY, Han J, et al. Pemetrexed plus cisplatin versus gemcitabine plus cisplatin according to thymidylate synthase expression in nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: a biomarker-stratified randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. (2015) 33:2450–6. 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.9324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang X, Yang B, Lu J, Zhan Z, Li K, Ren X. Pemetrexed-based chemotherapy in advanced lung adenocarcinoma patients with different EGFR genotypes. Tumour Biol. (2015) 36:861–9. 10.1007/s13277-014-2692-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park S, Park TS, Choi CM, Lee DH, Kim SW, Lee JS, et al. Survival benefit of pemetrexed in lung adenocarcinoma patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene rearrangements. Clin Lung Cancer. (2015) 16:e83–9. 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu J, Qi Y, Wu J, Shi M, Feng J, Chen L. Evaluation of plasma microRNA levels to predict insensitivity of patients with advanced lung adenocarcinomas to pemetrexed and platinum. Oncol Lett. (2016) 12:4829–37. 10.3892/ol.2016.5295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang YC, Zhou Q, Wu YL. The emerging roles of NGS-based liquid biopsy in non-small cell lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol. (2017) 10:167. 10.1186/s13045-017-0536-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishino M, Jackman DM, Hatabu H, Yeap BY, Cioffredi LA, Yap JT, et al. New Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: comparison with original RECIST and impact on assessment of tumor response to targeted therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. (2010) 195:W221–8. 10.2214/AJR.09.3928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thongprasert S, Duffield E, Saijo N, Wu YL, Yang JC, Chu DT, et al. Health-related quality-of-life in a randomized phase III first-line study of gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel in clinically selected patients from Asia with advanced NSCLC (IPASS). J Thorac Oncol. (2011) 6:1872–80. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822adaf7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang JC, Ahn MJ, Nakagawa K, Tamura T, Barraclough H, Enatsu S, et al. Pemetrexed continuation maintenance in patients with nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer: review of two East Asian trials in reference to PARAMOUNT. Cancer Res Treat. (2015) 47:424–35. 10.4143/crt.2013.266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang JJ, Chen HJ, Yan HH, Zhang XC, Zhou Q, Su J, et al. Clinical modes of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor failure and subsequent management in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. (2013) 79:33–9. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graham RP, Treece AL, Lindeman NI, Vasalos P, Shan M, Jennings LJ, et al. Worldwide frequency of commonly detected EGFR mutations. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (2018) 142:163–67. 10.5858/arpa.2016-0579-CP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Beasley MB, Chitale DA, Dacic S, Giaccone G, et al. Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol. (2013) 8:823–59. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318290868f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu YL, Zhong WZ, Li LY, Zhang XT, Zhang L, Zhou CC, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and their correlation with gefitinib therapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis based on updated individual patient data from six medical centers in mainland China. J Thorac Oncol. (2007) 2:430–9. Epub 2007/05/03. 10.1097/01.JTO.0000268677.87496.4c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Iafrate AJ, Wistuba, et al. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. JAMA. (2014) 311:1998–2006. 10.1001/jama.2014.3741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doroshow DB, Sanmamed MF, Hastings K, Politi K, Rimm DL, Chen L, et al. Immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: facts and hopes. Clin Cancer Res. (2019) 25:4592–602. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee SJ, Lee J, Park YS, Lee CH, Lee SM, Yim JJ, et al. Impact of smoking on mortality of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. (2014) 5:43–9. 10.1111/1759-7714.12051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsao AS, Liu D, Lee JJ, Spitz M, Hong WK. Smoking affects treatment outcome in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. (2006) 106:2428–36. 10.1002/cncr.21884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawaguchi T, Takada M, Kubo A, Matsumura A, Fukai S, Tamura A, et al. Performance status and smoking status are independent favorable prognostic factors for survival in non-small cell lung cancer: a comprehensive analysis of 26,957 patients with NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. (2010) 5:620–30. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d2dcd9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: The National Omics Data Encyclopedia (http://www.biosino.org/node/project/detail/OEP001054) and the European Genome-phenome Archive (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega/studies/EGAS00001004546).