Highlights

-

•

This case report contributes to the growing pool of reports concerning human papillomavirus (HPV) associated oral cancers.

-

•

There is a paucity of information in the literature regarding the malignant transformation of oral squamous cell papilloma (SCP).

-

•

The authors present a unique case of virus-associated cancer highlighting its progress and implications.

-

•

Immunocompromised patients and the elderly are at higher risk of malignancy and require closer observation.

Keywords: Oral squamous cell papilloma, Squamous cell carcinoma, Human papilloma virus, Oral verrucous hyperplasia, Koilocytosis, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Oral squamous papilloma is a benign tumor, but its potential for malignant transformation has yet to be studied. The authors report an unusual case presentation of an oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arising from a squamous cell papilloma (SCP).

Case presentation

A 61 years old immunocompromised female patient complained of an asymptomatic white mass on the buccal mucosa. The diagnosis of squamous cell papilloma (SCP) was made, and the benign nature of the lesion was confirmed by two biopsies. The lesion suddenly increased in size, and the third biopsy revealed a malignant squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) grade II. At this stage, radical surgical intervention was the treatment of choice, and reconstruction with a combination of the pectoralis major and deltopectoral flaps was performed.

Discussion

Clinical and histopathological diagnosis of oral squamous papilloma is challenging. Reconstruction of composite head and neck defects is another challenge, especially in elderly and immunocompromised patients. The whole process of diagnosis and progress of the presented case might provide useful knowledge regarding the nature of the lesion and its future management.

Conclusion

The authors emphasize the need for establishing a clear understanding of potentially malignant oral lesions. Close observation, multiple biopsies, early detection, precise diagnosis, and a multidisciplinary team approach are all of paramount importance.

1. Introduction

The worldwide updated cancer prevalence reported an increase in the incidence of oral cancer [1]. Despite that, it was regarded as the sixth most common cancer worldwide [2]. Oral squamous cell carcinoma accounts for 90% of the histologic type of oral cancer [3] and may or may not be preceded by oral potentially malignant disorders. The association of viruses and cancer was well documented. More than 20% of cancer prevalence worldwide could be related to infectious agents, including viruses, bacteria, and parasites. Over 15% of these cases are associated with viruses [4]. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is an epitheliotropic oncogenic DNA virus rarely found in oral mucosa, probably due to saliva clearance [5]. Nevertheless, more than 200 genotypes were detected in the oral mucosa [6]. HPV infection of the oral mucosa may result in benign or malignant disease. The role of HPV as an independent risk factor in oral carcinogenesis was well recognized in the literature [3]. HPV positivity claimed to override traditional prognostic indicators such as tumor grade and histological subtype [7]. However, other studies reported a non-significant association between HPV and oral cancer, suggesting its presence to be merely an incidental finding [8].

According to the classification of the World Health Organization (WHO), oral squamous cell papilloma is a benign hyperplastic exophytic localized proliferation with a verrucous or cauliflower-like morphology, which its base may be sessile or pedunculated [9]. It was reported to have two types: isolated-solitary in adults and multiple-recurring in children. The color of the lesion varies depending on the level of keratinization and vascularization [9]. Oral squamous papilloma is regarded as an innocuous lesion that is neither transmissible nor threatening [10]. The virulence and infectivity of oral papillomas are very low, unlike other HPV-induced lesions [11]. The site and size of oral papilloma can be used as risk factors for malignant transformation [12]. Although any intraoral site may be affected, the palate, tongue, lips, and gingiva are the most common. However, those present on the gingiva are associated with a higher risk of malignant transformation [13]. Also, if the size of the oral papilloma is larger than 10 mm, the risk increases [14].

Although untreated lesions of oral squamous papilloma do not usually change over time, several treatment modalities can be implemented. Conventional surgical excision without safety margin, cauterization or cryosurgery, electrocautery, intralesional injection of interferon, and the application of salicylic acid [15]. Laser ablation can also be used but with caution because viral particles are reported to be found in laser plumes after laser ablation [16]. The possibility of prophylactic HPV vaccination is certainly hope but may not be useful for treating existing disease. It is a necessity to develop effective prevention and treatment methods. The presented case report is in line with SCARE guidelines [17].

2. Case history

A 61 years old female patient, with a chief complaint of an intraoral white lesion covering the mucosa of the right cheek that appeared 2 years ago (Fig. 1). The patient was a non-smoker and non-drinker and suffered from end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The undertaken biopsy from the right buccal mucosa and histopathological examination revealed an oral squamous papilloma (Fig. 2). A year later, a second biopsy performed, and the pathological diagnosis of an oral squamous papilloma persisted.

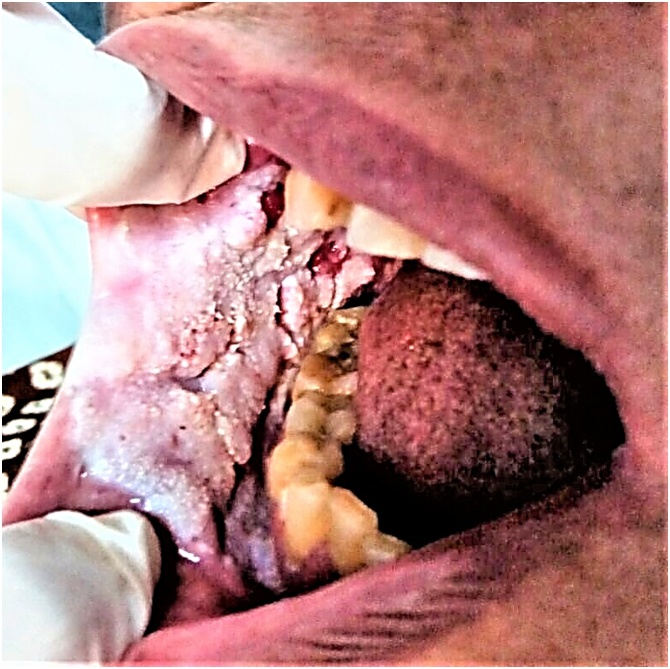

Fig. 1.

Showing the first clinical presentation of the lesion.

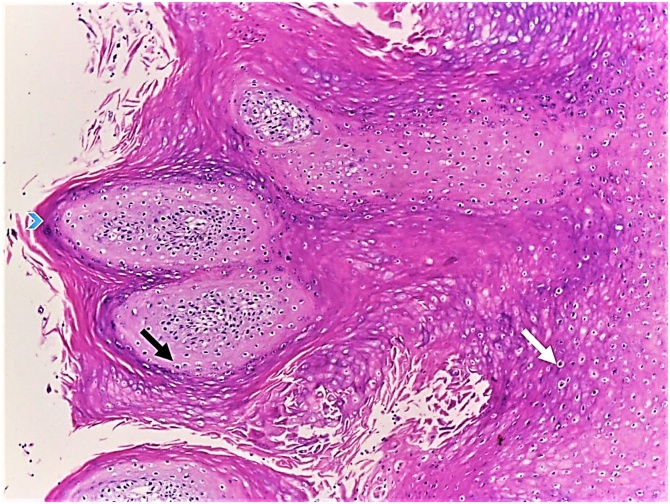

Fig. 2.

Showing oral viral papillomatous lesion (H&E, ×100), showing papillomatosis (blue arrow head), koilocytosis (black arrow) and dykeratotic figures (white arrow).

The patient presented 6 months later, complaining of the enlargement and change in the consistency of the lesion causing discomfort and dysfunction. Clinical examination revealed that the lesion extended to involve the floor of the mouth (Fig. 3) and the extraoral skin of the right cheek (Fig. 4). Bilateral suspicious lymph nodes were also noted. MRI and CT scan with contrast revealed a well-defined soft tissue mass measuring 6.2 × 2.5 × 3.5 cm along its maximum dimensions. The lesion was opposite the mandibular body (likely deep to buccinators muscle) with no evidence of bone erosion. It displayed a hypointense signal in T1WIs and hyperintense signal in STIR images with faint homogenous post-contrast enhancement. Multiple submental and bilateral submandibular lymph nodes were displaying no intrinsic calcifications or areas of breaking down. The largest of which was at the right submandibular group measuring 17 × 10 mm.

Fig. 3.

Showing the lesion extending to the floor of the mouth.

Fig. 4.

Showing intraoral and extraoral extension of the lesion.

The multidisciplinary team included surgical oncologists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, surgical pathologists, and maxillofacial prosthetists. The treatment plan was dictated by the severity of the condition. Neck dissection, hemimandibulectomy, and the placement of a reconstruction plate to bridge the mandibular defect were performed. The combination of Pectoralis major flap for intraoral reconstruction and deltopectoral flap for extraoral coverage were used. The two flaps raised at the same time without compromising the vascularity of each other as described by McGregor, I.A. [18]. The postoperative pathological diagnosis was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) grade II (Figs. 5, 6). The histopathological analysis of the dissected lymph nodes showed no metastatic involvement. The duration of postoperative follow-up was short since the patient died of complications of acute renal failure 1 month postoperative.

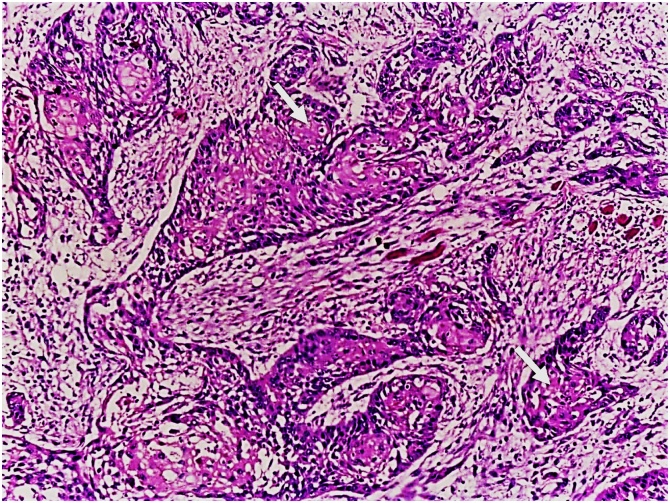

Fig. 5.

Showing moderately-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (H&E, ×100), showing some keratin pearls (white arrows).

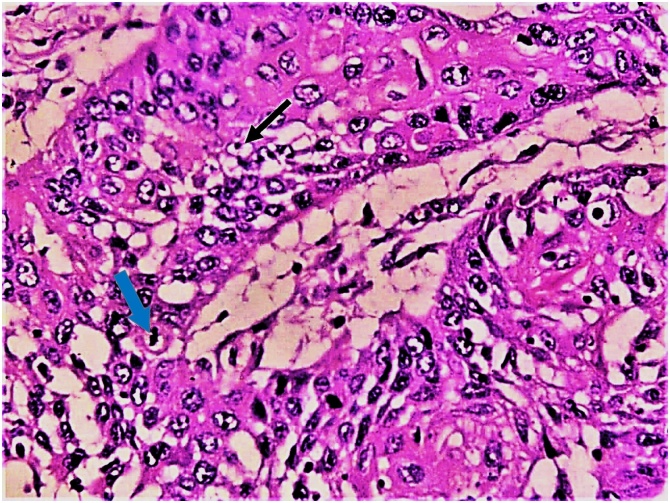

Fig. 6.

Showing moderately-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (H&E, ×400), showing mitotic figure (blue arrow) and prominent nucleoli (black arrow).

3. Discussion

Some authors define oral cancer as the group of neoplasms affecting any region of the oral cavity, oropharyngeal regions, and salivary glands, which accounts for the most majority of head and neck cancer [19]. While others define it as the neoplasm involving the oral cavity and begin at the lips and ends at the anterior pillars [7]. Controversial definitions and terminologies diminish the real impact of the disease and affect the decision-making process of treatment. The use of specific terms instead of generic terms shall be implemented. Clinical and histopathological diagnosis of oral squamous papilloma can be challenging. At clinical presentation, they may mimic invasive cancer while the histopathological features of a conventional oral squamous cell carcinoma may be absent [20]. When the histopathological sample is inconclusive; the pathology report shall reflect the possible differential diagnosis and recommend a second biopsy [14]. Although, it was suggested that the term oral verrucous hyperplasia (OVH) be used as a holding diagnosis when a definitive diagnosis of papillary lesions cannot be confirmed [14]. However, another study proposed that oral verrucous hyperplasia (OVH) may constitute a distinct entity and shall be considered in the classification of oral potentially malignant disorders [21].

In our case report, oral squamous papilloma (OSP) presented on the buccal mucosa which is not the usual site for this lesion. However, the buccal mucosa is reported to be the most common site of occurrence of oral verrucous carcinoma (OVC) [22]. Generally, oral squamous papilloma is asymptomatic, which can explain the late presentation and lack of follow-up shown by the patient in the current case report. Although alcohol and tobacco are considered major risk factors for oral cancer; their association was not observed in our study. A rising incidence of oral cancer in patients with no history of alcohol or tobacco reported by other authors [3,12]. The higher risk of carcinoma reported in elderly patients can be related to genetic susceptibility contributing to the phenotype [13,23]. The association of malignancy and immunosuppressive therapy is mediated through several pathogenic direct and indirect factors [24,25]. Therefore, the dose of immunosuppression shall be adjusted carefully to reduce the risk of malignant transformation.

Composite head and neck defects are a reconstructive challenge due to the complex anatomy and functional demands of this region. Free flaps are usually preferred and are considered the gold standard for reconstruction. Local and regional flaps have a long, reliable history and sometimes provide a superior option in some patient-specific conditions [26]. The pedicled pectoralis major flap constitutes one of the most universal flaps in head and neck reconstruction. It offers a three-dimensional reconstruction of the facial contour as well as protection of the great neck vessels in a single-stage operation. Choosing the best reconstructive option for each patient is controversial, and the surgeon must include the patient in the decision-making process. In the context of substantial pre-existing co-morbidity, the systemic factors of patients with advanced disease may implicate poor microcirculation and wound healing [27]. These patients are likely to prefer local flaps for reconstruction as the patient in our case report.

Herrero, R., et al., [28] performed a multicenter case-control study in nine countries, and Lingen, M.W., et al., [29] who sought data from 2005 to 2011 regarding HPV-associated oral squamous cell carcinoma. Although both series contributed much to our understanding of this evolving disease; they did not report clear follow-up and prognostic data [16]. In our case report, the patient’s death was a reflection of the high level of pre-existing co-morbidity rather than a treatment-related complication. The authors emphasize the need for establishing a clear understanding of potentially malignant lesions. Close observation, multiple biopsies, early detection, precise diagnosis, and a multidisciplinary team approach are all of paramount importance.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Sources of funding

The authors had no source of funding and no sponsors to this work.

Ethical Approval

The data presented in the current case report is reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee at our hospital. The patient signed a "release form" to give the authors the permission needed for publication.

Consent

“Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.”

Author contribution

Reem Hassan Saad: BDS, MSc, MFD RCSI (Corresponding Author, Data analysis, Manuscript Writing).

Samir Mohamed Halawa: BDS, MSc, MD (Lead Clinician, Data Collection, Patient’s surgery and follow up).

Ahmed Mohamed Zidan: MBBCh, MSc, MD, MD (Lead Clinician, Data Collection, Patient’s surgery and follow up).

Nashwa Mohamed Emara: MBBCh, MSc, MD (Data analysis).

Omar Abdellatif Abdelghany: BDS, MSc (Data collection).

Registration of research studies

This case study was written in accordance to Helsinki guidelines.

Guarantor

Reem Hassan Saad - BDS, MSc, MFDRCSI.

Samir Mohamed Halawa - BDS, MSc, MD.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Dr Mohamed Ibrahim M. AbdelGawad BDS, MSc.

References

- 1.Du M. Incidence trends of lip, oral cavity, and pharyngeal cancers: global burden of disease 1990-2017. J. Dent. Res. 2020;99(2):143–151. doi: 10.1177/0022034519894963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin D.M. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int. J. Cancer. 2001;94(2):153–156. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marur S. HPV-associated head and neck cancer: a virus-related cancer epidemic. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(8):781–789. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70017-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zur Hausen H. The search for infectious causes of human cancers: where and why. Virology. 2009;392(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campisi G., Giovannelli L. Controversies surrounding human papilloma virus infection, head & neck vs oral cancer, implications for prophylaxis and treatment. Head Neck Oncol. 2009;1:8. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Psyrri A., DiMaio D. Human papillomavirus in cervical and head-and-neck cancer. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2008;5(1):24–31. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Husain N., Neyaz A. Human papillomavirus associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: controversies and new concepts. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2017;7(3):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marx R.E., Stern D. Quintessence Pub. Co.; Hanover Park, IL: 2012. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: a Rationale for Diagnosis and Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toledano-Serrabona J. Recurrence rate of oral squamous cell papilloma after excision with surgical scalpel or laser therapy: a retrospective cohort study. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2019;24(4):e433–e437. doi: 10.4317/medoral.22943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaju P.P., Suvarna P.V., Desai R.S. Squamous papilloma: case report and review of literature. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2010;2(4):222–225. doi: 10.4248/IJOS10065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nogueira E.F. Partial glossectomy for treating extensive oral squamous cell papilloma. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bao Z. Clinicopathologic features of oral squamous papilloma and papillary squamous cell carcinoma: a study of 197 patients from eastern China. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2012;16(6):454–458. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W. Malignant transformation of oral verrucous leukoplakia: a clinicopathologic study of 53 cases. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2011;40(4):312–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zain R.B. Exophytic verrucous hyperplasia of the oral cavity - application of standardized criteria for diagnosis from a consensus report. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016;17(9):4491. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.(9).4491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh A.P. Oral squamous papilloma: report of a clinical rarity. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stojanov I.J., Woo S.B. Human papillomavirus and Epstein-Barr virus associated conditions of the oral mucosa. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2015;32(1):3–11. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agha R.A. The SCARE 2018 statement: Updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGregor I.A. A "defensive" approach to the island pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1981;34(4):435–437. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(81)90052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gan L.L. Prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a case-control study in Wuhan, China. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014;15(14):5861–5865. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.14.5861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kallarakkal T.G., Ramanathan A., Zain R.B. Verrucous papillary lesions: dilemmas in diagnosis and terminology. Int. J. Dent. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/298249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patil S. Exophytic oral verrucous hyperplasia: a new entity. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2016;7(4):417–423. doi: 10.1111/jicd.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franklyn J. Oral verrucous carcinoma: ten year experience from a tertiary care hospital in India. Indian J. Med. Paediatr. Oncol. 2017;38(4):452–455. doi: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_153_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho P.S. Malignant transformation of oral potentially malignant disorders in males: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:260. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutierrez-Dalmau A., Campistol J.M. Immunosuppressive therapy and malignancy in organ transplant recipients: a systematic review. Drugs. 2007;67(8):1167–1198. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767080-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azadarmaki R., Lango M.N. Malignant transformation of respiratory papillomatosis in a solid-organ transplant patient: case report and literature review. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2013;122(7):457–460. doi: 10.1177/000348941312200708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colletti G. Regional flaps in head and neck reconstruction: a reappraisal. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015;73(3):571.e1–571.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avery C.M. Indications and outcomes for 100 patients managed with a pectoralis major flap within a UK maxillofacial unit. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014;43(5):546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrero R. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: the International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003;95(23):1772–1783. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lingen M.W. Low etiologic fraction for high-risk human papillomavirus in oral cavity squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]