Key Points

Question

Is the Affordable Care Act (ACA) associated with a change in health care–related financial burden for families with children?

Findings

In this cohort study of US families with children using a difference-in-differences design, low- and middle-income families experienced a larger reduction in out-of-pocket costs after initiation of the ACA compared with higher income families who were less likely to benefit from ACA policies.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest that, although many ACA policies were adult focused, low- and middle-income families with children have benefited from reduced financial burden, but the amount of financial hardship post–ACA implementation remains substantial.

Abstract

Importance

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) sought to improve access and affordability of health insurance. Although most ACA policies targeted childless adults, the extent to which these policies also impacted families with children remains unclear.

Objective

To examine changes in health care–related financial burden for US families with children before and after the ACA was implemented based on income eligibility for ACA policies.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Data used for this cohort study were obtained from the 2000-2017 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, a nationally representative, population-based survey. Multivariable regression with a difference-in-differences estimator was used to examine changes in family financial burden before and after ACA implementation according to income-based ACA eligibility groups (≤138% [lowest-income], 139%-250% [low-income], 251%-400% [middle-income], and >400% [high-income] federal poverty level). The cohort included 92 165 families with 1 or more children (age ≤18 years) and 1 or more adult parents/guardians.

Exposures

Income-based eligibility groups during post-ACA years (calendar years 2014-2017) vs pre-ACA years (calendar years 2000-2013).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Family annual out-of-pocket (OOP) health care and premium cost burden relative to income. High OOP burden was determined based on a previously validated algorithm with relative cost thresholds that vary across incomes, and extreme OOP burden was defined as costs exceeding 10% of income. Premiums exceeding 9.5% of income were classified as burdensome and premiums relative to median household income defined an unaffordability index.

Results

Compared with high-income families who experienced a lesser change post-ACA implementation (high OOP burden, 1.1% pre-ACA vs 0.9% post-ACA), the lowest-income families saw the greatest reduction in high OOP burden (35.6% pre-ACA vs 23.7% post-ACA; difference-in-differences: −11.4%; 95% CI, −13.2% to −9.5%) followed by low-income families (24.6% pre-ACA vs 17.3% post-ACA, difference-in-differences: −6.8%; 95% CI, −8.7% to −4.9%) and middle-income families (6.1% pre-ACA vs 4.6% post-ACA, difference-in-differences: −1.2%; 95% CI, −2.3% to −0.01%). Although premiums rose for all groups, premium unaffordability was the least exacerbated for the lowest-, low-, and middle-income families compared with higher-income families.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this study suggest that low- and middle-income families with children who were eligible for ACA Medicaid expansions and Marketplace subsidies experienced greater reductions in health care–related financial burden after the ACA was implemented compared with families with higher incomes. However, despite ACA policies, many low- and middle-income families with children appear to continue to face considerable financial burden from premiums and OOP costs.

This cohort study examines financial burden experienced by families with children from before to after implementation of the Affordable Care Act.

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) implemented several policies to improve insurance coverage access and affordability, most notably Medicaid expansion for individuals with incomes 138% or less of the federal poverty level (FPL) and creation of the ACA Marketplaces. Marketplaces allow those without access to affordable employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) to purchase insurance, often with the assistance of premium subsidies known as advanced premium tax credits (APTCs), for those with incomes 400% or less than the FPL, and cost-sharing reductions (CSRs), for those with incomes 250% or less than the FPL.1 These policies have reduced out-of-pocket (OOP) health care costs, problems paying medical bills, and financial burden for adults.2,3

However, most studies on affordability are individual-level analyses limited to adults without considering the family context, particularly families with children.4,5,6,7 Children in low-income families were eligible for public insurance programs, such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), before ACA implementation and had lower rates of uninsurance than adults as a result.8 Many of the major ACA policies, such as the Medicaid expansion and Marketplaces, were targeted at improving coverage for childless adults, yet the positive effects of these policies may also indirectly extend to children. Facilitating parental coverage through Medicaid expansion has increased the likelihood that eligible but unenrolled children will obtain Medicaid or CHIP coverage (so-called welcome mat effects)9,10 and improved preventive care use for previously eligible and covered children.11 Thus, ACA policies directed at adults may improve health care–related financial burden for families with children by directly increasing affordable coverage for both children and their parents.12 Reductions in health care–related financial burden for families could further confer benefits by reducing overall family financial strain and allowing more money for other important needs.13 This reduced financial burden is all the more important during periods of public health and economic disruption, such as the coronavirus pandemic, when millions of parents have lost employment and associated coverage and need to find affordable insurance and health care for their families amidst other financial strains.14,15

The mechanism by which the ACA impacts families with children may vary by income. For lower-income families, uptake of Medicaid with limited cost sharing by newly eligible parents and previously eligible but unenrolled children is likely to have substantial benefits. For middle-income families without ESI, Marketplaces created affordable coverage options for parents, particularly for those taking advantage of subsidies, and their children, especially for families not eligible for CHIP. Conversely, some families with children may be prohibited from receiving ACA subsidies (so-called family glitch) when a parent’s ESI offer is deemed affordable at the individual level but prohibitive at the family level. Because it is presently unknown how these policies have collectively impacted families with children, we sought to evaluate financial burden, both from annual OOP health care costs and health insurance premiums, for families with children and examine the extent of reduced family health care–related financial burden after the implementation of the Medicaid expansion and Marketplace provisions of the ACA.

Methods

Data Source and Sample

Data were obtained from the 2000-2017 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey public use files, which do not include state identifiers. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey is a nationally representative survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population that collects data on health care spending and detailed sociodemographic characteristics over 2 calendar years for a rotating panel of US households (annual response rates, 44.2%-66.3%).16 Because data are deidentified, this study was deemed exempt from review by Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

Our sample included 92 165 annualized families with at least 1 child (age ≤18 years) and at least 1 adult parent/guardian (age ≥19 years); this sample included 51 815 unique families, of whom 77.9% contributed 2 years of data. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey defines families as 2 or more persons living together who are related by blood, marriage, or adoption; this definition also includes unmarried cohabitating persons who consider themselves a family unit and relatives identified as usual household residents (eg, college students living away from home). Although we did not include families with only young adult (age 19-25 years) children, our sample included 16 708 annualized families with both a child 18 years or younger as well as a young adult dependent.

ACA Eligibility Groups

We included families with any insurance type or no insurance and defined the exposure groups based on income eligibility for ACA policies: (1) Medicaid expansion eligible (incomes ≤138% of the FPL), (2) CSR eligible (incomes between 139% and 250% of the FPL, also eligible for APTCs), (3) APTC-only eligible (incomes between 251% and 400% of the FPL), and (4) no assistance (incomes above 400% FPL, used as a referent group).1 These eligibility groups pertain mostly to coverage for parents, as eligibility groups for Medicaid and CHIP for children vary by state but were largely unchanged by the ACA. In general, children in families with incomes less than 138% of the FPL have been eligible for Medicaid in most states, and children in families with incomes up to 175% to 405% of the FPL have been eligible for CHIP, even if their parent has other coverage.17 As these policies took effect in 2014, we examined eligibility groups in the post-ACA period (calendar years 2014-2017) compared with the pre-ACA period (calendar years 2000-2013).

Financial Burden

Respondents provided detailed data on annual OOP costs and income, which were adjusted for inflation to 2017 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index. We defined OOP costs as all payments for health care expenses for all family members in a given calendar year, excluding insurance premiums. Family income included income from all sources from all family members, with a $100 floor to account for zero or negative incomes. High financial burden was defined using income-based thresholds described and validated by Wisk et al18 (eg, OOP costs exceeding 3.45% of income for families with annual income <$20 000 or OOP exceeding 8.35% of income for families with annual income at $75 000). We used this measure because previous work demonstrated that different thresholds of OOP costs relative to income substantially outperform uniform thresholds for predicting subsequent use decisions for families with children.18 We also measured extreme financial burden with a more widely used absolute threshold of OOP costs 10% or more of family income.19

Respondents with private insurance provided detailed data on their insurance plans, including their annual premium contributions from 2001 to 2017. We summed annual insurance premiums for all private medical plans held by each family and classified high premium burden as having total family annual premium contributions greater than or equal to 9.5% of family income—consistent with the ACA’s definition of unaffordable premiums.7,20,21 Given year-over-year premium growth that exceeds income growth, a premium affordability index has been used to compare total (family and employer) premium costs relative to the US median household income for a given calendar year, with higher values indicating less-affordable premiums.22,23 Because only family premium contributions were available in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, we calculated a modified premium unaffordability index by dividing total family premium contributions by median household income.

Covariates

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey respondents self-reported detailed sociodemographic information about their family, including predisposing, enabling, and need factors: family size and composition, interview language, sex of the family respondent, race/ethnicity of the family respondent, marital status of the family respondent, highest educational attainment within the family, region of residence, and whether any family member was in fair/poor physical health or fair/poor mental health.24,25 For descriptive analyses, we additionally examined insurance coverage type (including actuarial features of Marketplace plans, eTable 1 in the Supplement) and insurance concordance within the family (families were concordant if all family members had the same insurance type). Because sources of coverage differ for children vs adults, we randomly selected 1 child and 1 adult family member and report their insurance coverage sources obtained at any point in the year.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), accounting for the complex sampling design and weighting scheme of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Family sociodemographic characteristics were examined descriptively overall and by ACA eligibility groups, with differences assessed with χ2 tests; insurance and financial burden were also examined by period (pre- vs post-ACA). The unadjusted prevalence of financial burden by year and eligibility group was assessed descriptively and to examine pre-ACA trends in burden (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Multivariable linear probability models were used to examine the prevalence of OOP and premium burden before vs after ACA implementation and by eligibility groups, with a difference-in-differences estimator used to assess the post-ACA changes for each eligibility group compared with among reference families (those not targeted by ACA policies), adjusting for covariates thought to influence family use and thus burden. Multivariable linear models were similarly used to examine premium unaffordability. Average marginal probabilities and means were output from multivariable models and used to visualize burden before and after ACA implementation. The significance threshold was set at P < .05 and all tests were 2-sided.

Because the first provisions of the ACA (eg, dependent coverage expansion) were implemented in 2010 and may have impacted family coverage and burden before 2014,26 we performed a sensitivity analysis defining the pre-ACA period as 2009 or earlier (rather than ≤2013). As a second sensitivity analysis, we further classified exposure to ACA policies by partitioning Medicaid-eligible families with 1 or more members covered by Medicaid/CHIP vs none and the other 3 eligibility groups by families without ESI offered (thus conceivably shopping in the nongroup market) vs with ESI offered.

Results

Eligibility groups differed significantly on sociodemographic characteristics (Table 1), with families targeted by ACA policies being more racially/ethnically diverse (eg, 38.8% of Medicaid-eligible families had a white non-Hispanic respondent vs 75.8% of families not eligible for assistance) and in poorer health compared with those not eligible for assistance (eg, 47.2% of Medicaid-eligible families had a member in fair/poor physical health vs 20.3% of families not eligible for assistance). Eligibility groups also differed with respect to insurance coverage, and all families were more likely to obtain Medicaid/CHIP (32.6% of children and 14.4% of adults pre-ACA vs 42.0% of children and 20.5% of adults post-ACA implementation) or nongroup private coverage (2.9% of children and 3.0% of adults pre-ACA implementation vs 3.6% of children and 5.9% of adults post-ACA implementation) and less likely to be uninsured after implementation of the ACA (19.7% of children and 28.6% of adults pre-ACA implementation vs 13.8% of children and 24.0% of adults post-ACA implementation) (Table 2).

Table 1. Sample Sociodemographic Characteristics by ACA Eligibility Groupa.

| Characteristic | Weighted % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Medicaid eligible | CSR eligible | APTC eligible | No assistance | |

| Total families, unweighted No. (weighted %) | 92 165 (100.0) | 29 797 (21.2) | 23 343 (22.5) | 18 379 (23.3) | 20 646 (33.0) |

| No. of children (≤18 y) | |||||

| 1 | 41.8 | 32.6 | 38.3 | 42.6 | 49.5 |

| 2 | 36.6 | 32.5 | 36.1 | 37.7 | 38.7 |

| ≥3 | 21.6 | 34.9 | 25.6 | 19.7 | 11.8 |

| No. of adults (≥19 y) | |||||

| 1 | 18.0 | 38.2 | 20.6 | 12.2 | 7.3 |

| 2 | 63.0 | 48.8 | 60.3 | 66.6 | 71.6 |

| ≥3 | 19.0 | 13.0 | 19.1 | 21.3 | 21.2 |

| Infants in family | |||||

| Any | 8.8 | 13.0 | 9.3 | 7.5 | 6.8 |

| None | 91.2 | 87.0 | 90.7 | 92.5 | 93.2 |

| Older persons (≥65 y) in family | |||||

| Any | 5.3 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 4.1 |

| None | 94.7 | 94.3 | 93.2 | 94.9 | 95.9 |

| Interview language | |||||

| English | 90.4 | 79.5 | 86.0 | 93.6 | 98.2 |

| Other | 9.6 | 20.5 | 14.0 | 6.4 | 1.8 |

| Sex of family respondent | |||||

| Female | 55.4 | 69.1 | 56.9 | 52.4 | 47.7 |

| Male | 44.6 | 30.9 | 43.1 | 47.6 | 52.3 |

| Family respondent race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic | |||||

| White | 60.6 | 38.8 | 53.1 | 66.2 | 75.8 |

| Black | 14.2 | 23.9 | 16.3 | 12.3 | 7.9 |

| Asian | 5.6 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 5.2 | 7.7 |

| Other | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Hispanic | 18.4 | 31.5 | 24.8 | 15.2 | 7.8 |

| Family respondent marital status | |||||

| Married/living with partner | 67.5 | 40.5 | 60.0 | 73.6 | 85.7 |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 18.0 | 26.5 | 22.1 | 17.0 | 10.6 |

| Never married | 14.4 | 33.0 | 17.9 | 9.4 | 3.8 |

| Highest educational attainment | |||||

| Less than high school degree | 7.9 | 23.2 | 9.2 | 3.1 | 0.6 |

| High school degree/GED | 26.5 | 42.2 | 36.2 | 25.4 | 10.5 |

| Some college (no degree) | 17.2 | 17.9 | 22.2 | 19.7 | 11.6 |

| Associate’s degree | 10.8 | 7.9 | 12.3 | 14.5 | 9.0 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 22.5 | 6.7 | 15.0 | 25.8 | 35.5 |

| Advanced degree | 15.1 | 2.1 | 5.1 | 11.4 | 32.8 |

| Region of residence | |||||

| Northeast | 17.7 | 15.7 | 15.7 | 17.2 | 20.7 |

| Midwest | 21.9 | 19.4 | 21.2 | 24.0 | 22.4 |

| South | 37.1 | 40.9 | 39.1 | 37.0 | 33.4 |

| West | 23.3 | 23.9 | 24.1 | 21.8 | 23.5 |

| Fair/poor physical health | |||||

| Any members | 31.7 | 47.2 | 36.7 | 29.0 | 20.3 |

| No members | 68.3 | 52.8 | 63.3 | 71.0 | 79.7 |

| Fair/poor mental health | |||||

| Any members | 20.5 | 31.9 | 23.2 | 17.9 | 13.2 |

| No members | 79.5 | 68.1 | 76.8 | 82.1 | 86.8 |

Abbreviations: ACA, Affordable Care Act; APTC, advanced premium tax credits; CSR, cost-sharing reductions; GED, general educational development.

All characteristics were significantly (globally) different across ACA eligibility groups at P < .001. Weighted row percentages are shown for the first row; weighted column percentages are shown elsewhere.

Table 2. Health Insurance Pre- and Post-ACA Implementation by Eligibility Groupa.

| Characteristic | ACA, Weighted % | P value | Weighted % | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (2000-2013) | Post (2014-2017) | Medicaid eligible | CSR eligible | APTC eligible | No assistance | ||||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||||

| Total families (weighted %) | 77.8 | 22.2 | 16.5 | 4.7 | 17.5 | 4.9 | 18.3 | 5.0 | 25.4 | 7.6 | |

| Child insurance status | |||||||||||

| Any private ESI/group | 59.9 | 55.3 | <.001 | 15.9 | 11.3 | 48.0 | 37.5 | 73.8 | 68.5 | 86.7 | 85.8 |

| Any private nongroup | 2.9 | 3.6 | .009 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 4.6 |

| Any Medicaid/CHIP | 32.6 | 42.0 | <.001 | 78.2 | 87.5 | 45.0 | 62.5 | 17.7 | 28.7 | 5.2 | 8.8 |

| Any other public coverage | 3.4 | 3.2 | .35 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 3.6 |

| Ever uninsured | 19.7 | 13.8 | <.001 | 25.1 | 16.0 | 26.2 | 19.4 | 19.6 | 14.9 | 11.8 | 8.2 |

| Adult insurance status | |||||||||||

| Any private ESI/group | 67.1 | 63.4 | <.001 | 23.8 | 18.0 | 59.9 | 52.7 | 80.7 | 77.7 | 90.3 | 89.4 |

| Any private nongroup | 3.0 | 5.9 | <.001 | 1.5 | 4.8 | 2.7 | 7.0 | 3.5 | 6.2 | 3.7 | 5.6 |

| Any Medicaid/CHIP | 14.4 | 20.5 | <.001 | 44.0 | 54.6 | 15.2 | 26.0 | 5.2 | 9.5 | 1.2 | 2.7 |

| Any other public coverage | 4.5 | 6.0 | <.001 | 6.6 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 7.2 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 3.4 | 4.8 |

| Ever uninsured | 28.6 | 24.0 | <.001 | 52.3 | 43.6 | 40.4 | 34.2 | 21.7 | 19.9 | 10.1 | 7.9 |

| Insurance concordance | .01 | ||||||||||

| Concordant family | 62.7 | 60.8 | 44.2 | 49.3 | 45.5 | 41.7 | 67.2 | 60.1 | 83.3 | 81.0 | |

| Discordant family | 37.3 | 39.2 | 55.8 | 50.7 | 54.5 | 58.3 | 32.8 | 39.9 | 16.7 | 19.0 | |

Abbreviations: ACA, Affordable Care Act; APTC, advanced premium tax credits; CHIP, Children’s Health Insurance Program; CSR, cost-sharing reductions; ESI, employer-sponsored insurance.

Insurance status pertains to 1 randomly selected child and 1 randomly selected adult family member. Insurance groups are not mutually exclusive and represent the prevalence of receipt of any coverage during the year from each coverage type. Weighted row percentages are shown for the first row; weighted column percentages are shown elsewhere.

Across all years, 13.9% of families experienced high OOP burden, 5.1% experienced extreme OOP burden, and 12.1% experienced premium burden. A significant decrease was seen from the pre- to post-ACA period overall in the prevalence of high (from 14.9% to 10.2%; difference: −4.6%; 95% CI, −5.4% to −3.9%) and extreme (from 5.5% to 3.6%; difference: −1.9%; 95% CI, −2.3% to −1.5%) OOP burden (Table 3). The prevalence of premium burden increased significantly from 11.6% before to 13.9% after ACA implementation (difference: 2.3%; 95% CI, 1.3%-3.3%).

Table 3. Unadjusted and Adjusted Changes in Financial Burden and Multivariable Difference-in-Differences Estimator.

| Characteristic | Unadjusted post- vs pre-ACA | % (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ACA, % | Post-ACA, % | Difference, % (95% CI) | Adjusted post- vs pre-ACA, differencea | Difference-in-differences, estimateb | ||

| High OOP burden | ||||||

| Overall | 14.9 | 10.2 | −4.6 (−5.4 to −3.9) | NA | NA | |

| Medicaid eligible | 35.6 | 23.7 | −11.9 (−13.8 to −9.9) | −11.5 (−13.3 to −9.7) | −11.4 (−13.2 to −9.5) | |

| CSR eligible | 24.6 | 17.3 | −7.3 (−9.2 to −5.4) | −6.9 (−8.8 to −5.1) | −6.8 (−8.7 to −4.9) | |

| APTC eligible | 6.1 | 4.6 | −1.5 (−2.5 to −0.5) | −1.3 (−2.4 to −0.2) | −1.2 (−2.3 to −0.01) | |

| No assistance | 1.1 | 0.9 | −0.2 (−0.6 to 0.1) | −0.1 (−0.6 to 0.3) | 0 [Reference] | |

| Extreme OOP burden | ||||||

| Overall | 5.5 | 3.6 | −1.9 (−2.3 to −1.5) | NA | NA | |

| Medicaid eligible | 15.4 | 9.3 | −6.0 (−7.3 to −4.8) | −5.9 (−7.1 to −4.8) | −6.0 (−7.2 to −4.7) | |

| CSR eligible | 5.7 | 3.6 | −2.1 (−3.0 to −1.2) | −2.0 (−2.9 to −1.1) | −2.0 (−3.0 to −1.0) | |

| APTC eligible | 2.9 | 2.4 | −0.5 (−1.2 to 0.2) | −0.5 (−1.2 to 0.3) | −0.5 (−1.4 to 0.4) | |

| No assistance | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 (−0.4 to 0.4) | 0.0 (−0.4 to 0.5) | 0 [Reference] | |

| Premium burdenc | ||||||

| Overall | 11.6 | 13.9 | 2.3 (1.3 to 3.3) | NA | NA | |

| Medicaid eligible | 35.6 | 35.6 | 0.0 (−3.3 to 3.3) | 0.7 (−2.6 to 3.9) | −0.6 (−3.9 to 2.8) | |

| CSR eligible | 19.1 | 23.8 | 4.7 (2.2 to 7.1) | 5.0 (2.6 to 7.5) | 3.8 (1.3 to 6.3) | |

| APTC eligible | 10.2 | 14.6 | 4.4 (2.6 to 6.2) | 4.6 (2.7 to 6.4) | 3.3 (1.4 to 5.3) | |

| No assistance | 3.1 | 4.3 | 1.2 (0.4 to 2.0) | 1.2 (0.4 to 2.1) | 0 [Reference] | |

Abbreviations: ACA, Affordable Care Act; APTC, advanced premium tax credits; CSR, cost-sharing reductions; NA, not applicable; OOP, out-of-pocket.

Adjusted post- vs pre-ACA changes were estimated from fully adjusted multivariable models including a difference-in-differences estimator and controlling for number of children in the family, number of adults in the family, number of infants in the family, number of older persons (age ≥65 y) in the family, interview language, sex of the family respondent, race/ethnicity of the family respondent, marital status of the family respondent, highest educational attainment within the family, region of residence, family members in fair/poor physical health, and family members in fair/poor mental health.

The difference-in-differences estimator shows the adjusted relative change in burden for each eligibility group compared to families who were not eligible for assistance.

Premiums are among families who reported any private coverage from 2001 on (n = 57 442).

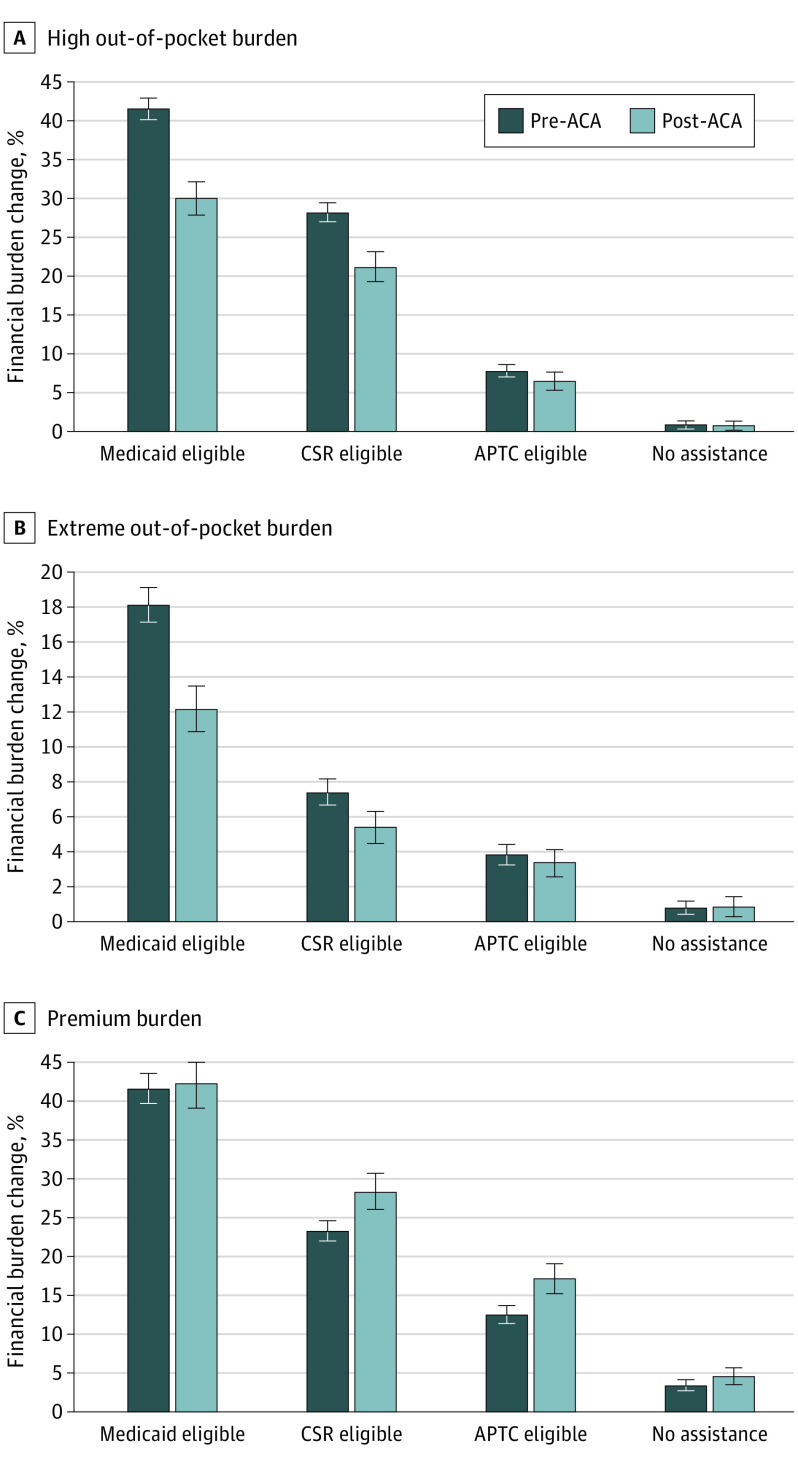

Adjusted difference-in-differences estimates revealed that the reduction in high financial burden was largest for Medicaid-eligible families (adjusted relative change in burden compared with families not eligible for assistance: −11.4%; 95% CI, −13.2% to −9.5%) (Table 3 and Figure), followed by CSR-eligible families (−6.8%; 95% CI, −8.7% to −4.9%) and APTC-eligible families (−1.2%; 95% CI, −2.3% to −0.01%). The ACA also reduced the extreme financial burden for Medicaid-eligible families (−6.0%; 95% CI, −7.2% to −4.7%) and CSR-eligible families (−2.0%; 95% CI, −3.0% to −1.0%) compared with families ineligible for assistance.

Figure. Predictive Margins for Family Financial Burden Before and After Implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Pre-ACA vs post-ACA adjusted marginal probability of financial burden by ACA eligibility group for families with high out-of-pocket burden (A), extreme out-of-pocket burden (B), and premium burden (C) output from fully adjusted multivariable models including a difference-in-differences estimator and controlling for number of children in the family, number of adults in the family, number of infants in the family, number of older persons (age ≥65 years) in the family, interview language, sex of the family respondent, race/ethnicity of the family respondent, marital status of the family respondent, highest educational attainment within the family, region of residence, family members in fair/poor physical health, and family members in fair/poor mental health. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. APTC indicates advanced premium tax credits; CSR, cost-sharing reductions.

Compared with the increase in premium burden seen for families not eligible for assistance, families eligible for either CSR or APTC saw larger increases in premium burden after ACA implementation, while Medicaid-eligible families did not (Table 3). Despite the overall increase in premiums, the ACA mitigated the magnitude of this increase in premium unaffordability for Medicaid-eligible families, CSR-eligible families, and APTC-eligible families relative to families ineligible for assistance (eTable 2 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Sensitivity analyses using an alternative preperiod revealed larger estimates of the association between the ACA and financial burden, but results were otherwise consistent with the main findings (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Larger estimates were also noted with refined exposure groups and the increase in premium burden from pre- to post-ACA implementation was associated with CSR- and APTC-eligible families with ESI offered (unexposed); there was no significant increase for CSR- and APTC-eligible families without ESI (exposed) (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Discussion

We identified substantial reductions in health care–related OOP burden for US families with children after the implementation of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and Marketplace CSR and APTC subsidies. These ACA policies, which primarily targeted low- and middle-income adults who were most vulnerable to experiencing high financial burden before ACA implementation, have likely indirectly benefited children by reducing financial burden in their families. However, despite these gains, the financial burden in low- and middle-income families remains markedly higher than that of high-income families following ACA implementation.

We found that families with children and income eligibility for Medicaid expansion and/or Marketplace plans with CSRs were most likely to benefit from the ACA’s moderating influence on financial hardship. However, concurrently, we noted that, at modestly higher incomes (>250% of the FPL), the benefits of the ACA appear to be less marked. Although modest reductions in high (but not extreme) financial burden were noted, many of the middle-income families may still experience financial burden from high deductibles and other OOP requirements in Marketplace plans without the benefit of CSRs.27 Advanced premium tax credits allow families at greater than 250% of the FPL to obtain Marketplace plans at lower premiums, but plans with lower premiums may also have lower actuarial value and higher OOP cost sharing.28 Only 16% of Marketplace plans obtained by this sample from 2015 to 2017 were a platinum or gold level plan, while 52% were silver (eTable 1 in the Supplement), suggesting that families in Marketplace plans may prioritize lower monthly premiums over lower OOP costs and thus still be at risk for high OOP burden.29 Families with incomes in this range may also be above CHIP eligibility and enroll their children with them in Marketplace plans, exposing both children and parents to high deductibles and cost sharing.

Even for children who have not directly benefited from obtaining coverage because of these ACA policies, there may be indirect benefits from improved coverage and affordability for their parents and subsequent reductions in cost-related delayed/forgone care, financial hardship, and associated sequelae, such as evictions and foreclosures30 and psychological distress among parents.4 These cost-related improvements in social determinants of health are likely to create a substantial return-on-investment for the health and well-being of children in both the short and long term, although not equally distributed given state variation in policies such as the Medicaid expansion.

Yet even after implementation of the ACA, the prevalence of financial burden among the most vulnerable families remains high.31 After the ACA was implemented, we found that more than 1 in 5 low-income (≤250% of the FPL) families with children reported high financial burden, and more than 1 in 16 spent 10% or more of their income on OOP costs. While children in low-income families are protected from high OOP costs and premiums if they are enrolled in Medicaid/CHIP, coverage options for their parents have not been as generous. Medicaid for children prohibits most cost sharing; however, this is not the case for adult Medicaid, and OOP costs can be significantly higher in Marketplace plans than CHIP.32 Policy solutions for easing financial hardship for this population should continue to focus on better supporting affordable insurance coverage with reduced cost sharing for parents, which may in turn also improve the uptake of affordable coverage for their children and reduce financial burden in their families.33

Despite gaining eligibility for Medicaid or Marketplace plans, some families have not taken up these opportunities31,34 and ESI remains the predominant coverage for most families overall. Low- and middle-income families that are offered ESI plans that are considered affordable are unable to benefit from Marketplace assistance (family glitch), limiting the effectiveness of ACA policies. Our sensitivity analysis suggests that the ACA had a greater association with premium burden for low- and middle-income families without access to ESI but did little to mitigate burden for those with ESI availability. The family glitch may contribute to the differential experiences of premium burden for these families with otherwise similar incomes.

Policy Implications

Despite the gains in coverage and affordability for families with children after the ACA, there are still concerning levels of financial burden in these families, particularly those with incomes 250% or lower than the FPL. Extending Medicaid expansion to other states could indirectly benefit children by increasing coverage for parents and other family members and improving access to affordable health care.35,36 Streamlining Medicaid/CHIP enrollment for children via “no wrong door” policies in state and federal ACA Marketplaces can enhance the impact of ACA policies targeted at adult coverage to increase coverage for eligible but previously unenrolled children.10 Revising the definition of affordable coverage may also be warranted, especially for family-level ESI. Without knowing the premium of ESI that was offered but not taken up, we cannot directly assess the prevalence of the family glitch. However, our finding that nearly 15% of middle-income families and 27% of those with low incomes had post-ACA premiums over the ACA premium affordability threshold of 9.5% of income suggests that some income-eligible families are not able to take advantage of premium subsidies.

Potential restrictions of the ACA and its components could directly negate the improvements to family financial burden noted in this study and have other indirect negative effects on children. The ACA’s individual mandate may have played a role in nudging families to take advantage of these coverage options,37 but as this policy is no longer enforced, some families may decide to opt out of insurance coverage and could experience an increase in health care–related financial burden as a result. Our study suggests that CSRs were beneficial in reducing financial burden. Removal of CSRs has the potential to make health care difficult to afford for those eligible and those ineligible for subsidies in the nongroup market who may be indirectly affected by compensatory sharp increases in premiums owing to defunding of CSRs. In addition, alterations that would limit affordable coverage options are worrisome in situations such as the coronavirus pandemic or other economic downturns if parents lose job-related coverage and need to turn to Medicaid or Marketplaces.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. First, without data on state of residence that could distinguish families in Medicaid expansion states, as well as the delayed phase-in of Medicaid expansion across the post-ACA period, our findings may misestimate the association of actual parental Medicaid eligibility with financial burden. Similarly, eligibility groups identified families who were potentially eligible for ACA policies based on self-identified family structure and income rather than applying exact program eligibility criteria or conditioning on families’ actual receipt of CSR or APTC subsidies, potentially underestimating the specific correlation of uptake of ACA coverage with financial burden. In addition, even with a quasi-experimental design and multivariable adjustment, there are substantial differences between income-based eligibility groups and we lack a maximally similar comparator group; still, this imperfect approach has been used previously to provide suggestive, although not causal, evidence of policy influence on financial burden.7,20,21

Conclusions

Families with children with incomes targeted for ACA Medicaid expansions and Marketplace subsidies have seen reductions in OOP financial burden compared with those with higher incomes not targeted by the ACA, although those with incomes below 250% of the FPL remain at risk for high financial burden. Policy makers and child health advocates should work to preserve and improve policies that increase coverage and affordability for parents, in addition to policies that directly address children’s health care coverage. Doing so may reduce health care–related financial strain in families with children that can lead to delayed/forgone care due to cost,13,18 with the goal of improving children’s access to needed care and family well-being.

eTable 1. Characteristics of Marketplace Insurance Plans Among Families With Children

eFigure 1. Time Trends in Financial Burden by ACA Eligibility Group

eTable 2. Unadjusted and Adjusted Changes in Premium Unaffordability Index and Multivariable Difference-in-Differences Estimator

eFigure 2. Predictive Margins for Family Premium Unaffordability Index Pre- and Post-ACA

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analysis for Changes in Financial Burden Using an Alternative Pre-Period

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analysis for Changes in Financial Burden Using Refined ACA Exposure Groups

References

- 1.Explaining health care reform: questions about health insurance subsidies. Kaiser Family Foundation website. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/explaining-health-care-reform-questions-about-health/

- 2.Blavin F, Karpman M, Kenney GM, Sommers BD. Medicaid versus Marketplace coverage for near-poor adults: effects on out-of-pocket spending and coverage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(2):299-307. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim U, Rose J, Koroukian S. Access and affordability in low- to middle-income individuals insured through health insurance exchange plans: analysis of statewide data. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):792-795. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04826-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMorrow S, Gates JA, Long SK, Kenney GM. Medicaid expansion increased coverage, improved affordability, and reduced psychological distress for low-income parents. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(5):808-818. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selden TM, Lipton BJ, Decker SL. Medicaid expansion and marketplace eligibility both increased coverage, with trade-offs in access, affordability. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(12):2069-2077. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guth M, Garfield R, Rudowitz R The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: updated findings from a literature review. Kaiser Family Foundation website. Accessed March 17, 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review/

- 7.Liu C, Tsugawa Y, Weiser TG, Scott JW, Spain DA, Maggard-Gibbons M. Association of the US Affordable Care Act with out-of-pocket spending and catastrophic health expenditures among adult patients with traumatic injury. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e200157. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blavin F, Holahan J, Kenney G, Chen V. A decade of coverage losses: implications for the Affordable Care Act. Urban Institute; February 24, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson JL, Moriya AS. Medicaid expansion for adults had measurable “welcome mat” effects on their children. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1643-1651. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson JL, Moriya AS. Association between Marketplace policy and public coverage among Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program–eligible children and parents. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):881-882. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkataramani M, Pollack CE, Roberts ET. Spillover effects of adult Medicaid expansions on children’s use of preventive services. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20170953. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeVoe JE, Tillotson CJ, Angier H, Wallace LS. Predictors of children’s health insurance coverage discontinuity in 1998 versus 2009: parental coverage continuity plays a major role. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(4):889-896. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1590-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wisk LE, Witt WP. Predictors of delayed or forgone needed health care for families with children. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):1027-1037. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karpman M, Gonzalez D, Kenney GM Parents are struggling to provide for their families during the pandemic: material hardships greatest among low-income, Black, and Hispanic Parents. Urban Institute website. Accessed May 2020. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/parents-are-struggling-provide-their-families-during-pandemic

- 15.Levitt L. COVID-19 and massive job losses will test the US health insurance safety net. JAMA Forum. Published May 28, 2020. Accessed July 29, 2020. https://jamanetwork.com/channels/health-forum/fullarticle/2766729?utm_source=silverchair&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=article_alert-jhf&utm_content=olf&utm_term=052820 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.MEPS-HC Response Rates by Panel Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. August 30, 2019. Accessed May 19, 2020. https://meps.ahrq.gov/survey_comp/hc_response_rate.jsp [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks T, Roygardner L, Artiga S, Pham O, Dolan R Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies as of January 2020: findings from a 50-state survey. Kaiser Family Foundation website. Accessed March 26, 2020. https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2020-findings-from-a-50-state-survey-executive-summary/

- 18.Wisk LE, Gangnon R, Vanness DJ, Galbraith AA, Mullahy J, Witt WP. Development of a novel, objective measure of health care–related financial burden for US families with children. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(6):1852-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banthin JS, Bernard DM. Changes in financial burdens for health care: national estimates for the population younger than 65 years, 1996 to 2003. JAMA. 2006;296(22):2712-2719. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.22.2712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldman AL, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Bor DH, McCormick D. Out-of-pocket spending and premium contributions after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):347-355. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu C, Maggard-Gibbons M, Weiser TG, Morris AM, Tsugawa Y. Impact of the Affordable Care Act insurance Marketplaces on out-of-pocket spending among surgical patients. Published online March 26, 2020. Ann Surg. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emanuel EJ, Glickman A, Johnson D. Measuring the burden of health care costs on US families: the Affordability Index. JAMA. 2017;318(19):1863-1864. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.15686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glickman A, Weiner J The burden of health care costs for working families: a state-level analysis. University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics website. April 1, 2019. Accessed August 24, 2020. https://ldi.upenn.edu/brief/burden-health-care-costs-working-families

- 24.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9(3):208-220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1-10. doi: 10.2307/2137284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wisk LE, Sharma N. Inequalities in young adult health insurance coverage post-federal health reform. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(1):65-74. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4723-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen W, Page TF. Impact of health plan deductibles and health insurance marketplace enrollment on health care experiences. Med Care Res Rev. 2018;1077558718810129. doi: 10.1177/1077558718810129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drake C, Anderson DM. Terminating cost-sharing reduction subsidy payments: the impact of marketplace zero-dollar premium plans on enrollment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(1):41-49. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hero JO, Sinaiko AD, Kingsdale J, Gruver RS, Galbraith AA. Decision-making experiences of consumers choosing individual-market health insurance plans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(3):464-472. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallagher EA, Gopalan R, Grinstein-Weiss M. The effect of health insurance on home payment delinquency: Evidence from ACA Marketplace subsidies. J Public Econ. 2019;172(C):67-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.12.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fung V, Liang CY, Hsu J. Health Insurance and Health Care Affordability Perceptions Among Individual Insurance Market Enrollees in California in 2017. California Health Care Foundation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peltz A, Davidoff AJ, Gross CP, Rosenthal MS. Low-income children with chronic conditions face increased costs if shifted from CHIP To Marketplace plans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(4):616-625. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeVoe JE, Marino M, Angier H, et al. . Effect of expanding Medicaid for parents on children’s health insurance coverage: lessons from the Oregon experiment. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(1):e143145. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sinaiko AD, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB, Lieu T, Galbraith A. The experience of Massachusetts shows that consumers will need help in navigating insurance exchanges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(1):78-86. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karpman M, Kenney GM, Gonzalez D Health care coverage, access, and affordability for children and parents: new findings from March 2018. Urban Institute: Health Policy Center; September 6, 2018 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis MM. Evidence for a uniform Medicaid eligibility threshold for children and parents. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20173236. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wisk LE, Finkelstein JA, Toomey SL, Sawicki GS, Schuster MA, Galbraith AA. Impact of an individual mandate and other health reforms on dependent coverage for adolescents and young adults. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1581-1599. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Characteristics of Marketplace Insurance Plans Among Families With Children

eFigure 1. Time Trends in Financial Burden by ACA Eligibility Group

eTable 2. Unadjusted and Adjusted Changes in Premium Unaffordability Index and Multivariable Difference-in-Differences Estimator

eFigure 2. Predictive Margins for Family Premium Unaffordability Index Pre- and Post-ACA

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analysis for Changes in Financial Burden Using an Alternative Pre-Period

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analysis for Changes in Financial Burden Using Refined ACA Exposure Groups