Abstract

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a cutaneous type IV hypersensitivity immune reaction mounted against substances in contact with the skin to which the patient has been sensitized. ACD is common, affecting approximately 72 million Americans per year, and is more common in women. One common contact allergen group is acrylates, which are monomers that are polymerized in the making of glues, adhesives, and plastic materials. It is the monomers that are sensitizing, whereas the final polymers are inert. Acrylates were the 2012 Contact Allergen of the Year with the specific acrylate, isobornyl acrylate, being the 2020 Contact Allergen of the Year. This article reviews the history of acrylate use, epidemiology, and both known and emerging sources of acrylates resulting in ACD.

Keywords: Acrylates, Contact dermatitis, Isobornyl acrylate, Super glue, Nail adhesives, Diabetic pump adhesives

Introduction

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a cutaneous type IV hypersensitivity immune reaction mounted against substances in contact with the skin to which the patient has been sensitized (Kostner et al., 2017). ACD is common, affecting approximately 72 million Americans per year, and is more common in women (Bickers et al., 2006). One common contact allergen group is acrylates, which are monomers that are polymerized into the making of glues, adhesives, and plastic materials. The monomers are sensitizing, whereas the final polymers are inert. Acrylates were the 2012 Contact Allergen of the Year with the specific acrylate isobornyl acrylate (IBOA) being the 2020 Contact Allergen of the Year (Aerts et al., 2020, Sasseville, 2012). This article reviews the history of acrylate use, epidemiology, and both known and emerging sources of acrylates resulting in ACD.

Acrylates and history of use

Acrylates are salts, or esters, of acrylic acid. Acrylic acid was first synthesized in 1843, followed by methacrylic acid in 1865. The polymerization of acrylates was done in 1877 by German chemists Fittig and Paul (Sasseville, 2012). However, their use became more widespread after the creation of products such as Plexiglas, a transparent and nearly shatterproof glass alternative made of polymethyl methacrylate, which was patented in 1933. The first case of ACD to acrylates was documented in 1941 (Stevenson, 1941) and would be the first of many as the number and diversity of commercial products containing acrylates continued to increase (Sasseville, 2012).

Epidemiology

The exact epidemiology of acrylate-induced contact dermatitis is difficult to determine. Among patch-tested patients studied by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group from 2015 to 2016, rates of reactions to acrylates ranged from 3.4% for 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate to 1.7% for ethyl acrylate and 1.4% for methyl methacrylate, with 79% of these having at least possible relevance (DeKoven et al., 2018). Other studies of patch-tested populations in Canada, Sweden, and Singapore found that overall incidence ranged from 1.0% to 1.4% (Drucker and Pratt, 2011, Goon et al., 2008). Similarly, a majority of patients (72%) had clinically relevant exposure to acrylates (Drucker and Pratt, 2011). In a retrospective review of patients with positive extended methacrylate and acrylate testing, 67.6% of cases were occupation related, most commonly nail beauticians (80%), followed by dental workers and industrial workers (Ramos et al., 2014).

Types and sources of acrylates

Acrylates vary in their chemical structure, commercial use, and sensitization capacity (Conde-Salazar et al., 2007, Sasseville, 2012). Acrylates are typically categorized based on their chemical structure, with mono(meth)acrylates, diacrylate/triacrylates, and cyanoacrylates being the common groupings.

Mono(meth)acrylates

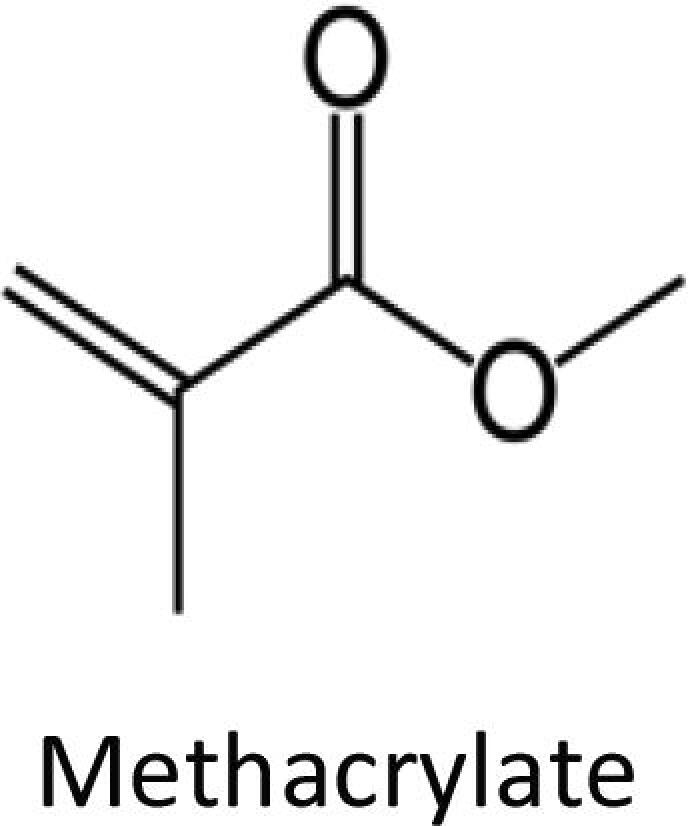

Monoacrylates are defined by a structure of only 1 vinyl group (Fig. 1; Sasseville, 2012) and are used in the production of rubber, eyeglass frames, dentures, hearing aids, and artificial nails. Artificial nails are molded in a 2-part mixture of both liquid monomer and polymer powder that polymerizes in ambient light (Sasseville, 2012).

Fig. 1.

Methacrylate.

Diacrylates and triacrylates

Diacrylates and triacrylates contain 2 or 3 reactive acrylic groups (Sasseville, 2012, Scheman et al., 2019) and are more commonly used in dental composite materials, artificial nails, and ultraviolet-cured inks (Sasseville, 2012).

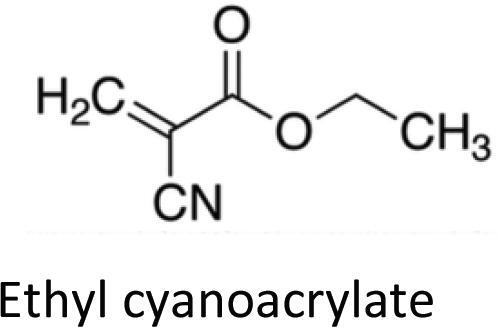

Cyanoacrylates

Cyanoacrylates are most commonly used in fast-acting glues (e.g., superglue), nail glues for press-on nails, continuous glucose monitors (Fig. 2), and medical adhesives (2-octyl cyanoacrylate or Dermabond; Aschenbeck and Hylwa, 2017, Chou et al., 2017, Durando et al., 2014, Muttardi et al., 2016).

Fig. 2.

Ethyl cyanoacrylate.

Acrylate cross polymers

The manufacturing of acrylates typically involves using a monomer of either acrylate or methacrylate that is then polymerized into the final product. It is these monomers that are acutely sensitizing and allergenic (Drucker and Pratt, 2011, Geukens and Goossens, 2001). Polymerization (hardening) of monomers renders them inert. Several methodologies can be used for polymerization: self-curing, catalyst-driven, ultraviolet light, or heat processes. Because these methodologies differ in the degree to which they result in a fully polymerized final product, some products can contain more residual monomers than others and thus be more or less sensitizing (Scheman et al., 2008).

Cross reactivity

The sensitizing potential of acrylates is a function of the chemical structure. Diacrylates have strong sensitization potential, but methacrylates are only moderately or weakly sensitizing (Conde-Salazar et al., 2007). Cyanoacrylates were initially deemed nonsensitizing because cyanoacrylate polymerization is quickly triggered by moisture on the bonded surface (e.g., metals, ceramic, glass, rubber, biologic tissue) and occurs within minutes (Sasseville, 2012). However, cyanoacrylates are now well documented sources of ACD (Chou et al., 2017). Despite significant cross reactivity between many acrylates, allergy to cyanoacrylates has not been shown to cross-react with other (meth)acrylates (Chou et al., 2017).

Exposure to incompletely polymerized acrylates will induce broad cross-reactivity or cosensitivity to acrylates and has been documented to result in systemic contact dermatitis in rare cases (Sauder and Pratt, 2015). The recent emergence of home nail applications with acrylate curing using ultraviolet light has extended the potential risk of sensitization because patients have more direct contact with the monomers without complete curing (DeKoven et al., 2018).

Clinical features

In a review of 32 patients with ACD due to acrylate exposure, presentations varied widely. The most common pattern was chronic hand eczema with cracked pulpitis, paronychia, and nail dystrophy. Other sites of involvement included the thighs, wrists and forearms, face, oral mucosa, and eyelids (Ramos et al., 2014). Researchers have suggested that patients who present with periungual dermatitis and nail dystrophy concomitant with the use of artificial nails have ACD to acrylate in the differential (Bjorkner, 2006). Airborne sensitization to acrylates has also resulted in respiratory symptoms in rare cases (Muttardi et al., 2016, Ramos et al., 2014).

Potential protection

Recommending protection from acrylates can be challenging because products made with acrylates frequently are not labeled, the degree to which the final product is polymerized is not readily evident to the consumer, and cross reactivity between classes of acrylates is common (Darre et al., 1987). Additionally, barrier protection from (meth)acrylic monomers in the form of gloves is often not adequate because monomers easily penetrate rubber (including latex) and polyethylene gloves (Andersson et al., 2000). Gloves made of neoprene, neoprene with nitrile, butyl rubber, or polyvinyl alcohol can increase protection for up to a few hours against acrylates (Horner and Anderson, 2009). Double/triple gloving may help but is not always a practical solution in occupational settings that require fine dexterity. In patients with facial lesions and mucosal involvement, the use of protective masks during work, such as nail trimming, could potentially offer a reduction in airborne exposure (Ramos et al., 2014).

In cases of acrylate-induced ACD in wearable products, such as dentures, boiling has been found to be of some benefit via curing residual monomers (Horner and Anderson, 2009). In the case of hearing aids, asking for further curing or considering replacements made of alternative materials, such as silicone, can be helpful (Horner and Anderson, 2009).

For patients with an allergy to adhesive products due to acrylates, finding an alternative is optimal. When such possibilities do not exist, as in the case of wearable medical devices (e.g., diabetic glucose sensor or insulin infusion sets), improved tolerance may occur with a protective barrier, such as Tegaderm (3M, St. Paul, MN; Aschenbeck and Hylwa, 2017).

In a 13-year review that was completed in 2016, four individual (meth)acrylates (2-hydroxyethyl acrylate, 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate, bisphenol A glycerolate dimethacrylate, and ethyl acrylate) were found to identify 90.4% of positive cases (Spencer et al., 2016). This review also revealed a shift in exposure from a history of manufacturing toward acrylic nail sources. At that time, wound dressings were also identified as an emerging source of sensitization (Spencer et al., 2016).

Emerging acrylate allergens

Isobornyl acrylate

IBOA has been a documented allergen since 1995, but reports of this allergen have been on the rise in the diabetic population from IBOA causing ACD from adhesives/glues in glucose sensors and insulin infusion sets (Busschots et al., 1995, Herman et al., 2017). Pyl et al. (2020) found contact dermatitis due to isobornyl acrylate in 3.8% of pediatric and adult patients using FreeStyle Libre. In patients who used FreeStyle Libre or Enlite and had suspected ACD, 68% to 81% of patients screened for IBOA were found to have a positive patch-test reaction (Hyry et al., 2019, Pyl et al., 2020). These emerging reports have earned IOBA the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) Allergen of the Year Award for 2020. It is notable that acrylates are not available on commercially available patch-test kits. IBOA is not currently on the surveillance panel of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group or the ACDS 80-allergen core series and thus must be purchased separately and applied when clinical suspicion of this allergen is high (Hyry et al., 2019, Mine et al., 2019, Shinkawa et al., 2019). IBOA is currently available for purchase through Chemotechnique Diagnostics. To our knowledge, two glucose monitors (Freestyle Libra and Enlite) have been found to contain IBOA, with two alternatives without IBOA (Dexcom G6 and Eversense) (Kamann et al., 2019, Oppel et al., 2019).

An additional emerging concern around IBOA is possible sensitization to many alkyl glucosides because IBOA is used as a plasticizer in various plastics and has the potential to be leached from containers via surfactant properties of alkyl glucosides (Loranger and Alfalah, 2017, Durando et al., 2014, Foti et al., 2016). Increased suspicion would require further investigation with patch testing with IBOA in patients sensitized to alkyl glucosides (Kamann et al., 2019).

Ethyl cyanoacrylate

Ethyl cyanoacrylates have also been reported in diabetic devices (Aschenbeck and Hylwa, 2017). Notably, this allergen was not present in the adhesives used to adhere the device to the skin but rather within the device itself and exemplifies the ability of cyanoacrylates to penetrate perceived barriers (Aschenbeck and Hylwa, 2017).

2-octyl cyanoacrylate

Dermabond (2-octyl cyanoacrylate) is a topical wound-closure adhesive frequently used for its ease of use and overall patient satisfaction. Reports of ACD to this product are not uncommon, with the incidence of ACD to Dermabond reported at 2% (Davis and Stuart, 2016, Dunst et al., 2010, Durando et al., 2014, El-Dars et al., 2010, Hivnor and Hudkins, 2008). Importantly, 2-octyl cyanoacrylate does not cross react with other acrylates, such as ethyl cyanoacrylate, which is the standard cyanoacrylate on patch-test series. Thus, in cases where suspicion of ACD to 2-ocyl cyanoacrylate is high, Dermabond must be applied to the skin because there is no surrogate patch-testing hapten currently available. Fig. 3 shows a positive patch-test reaction to Dermabond.

Fig. 3.

Positive patch-test reaction to Dermabond.

Butyl acrylate

ACD to butyl acrylate has been reported from Mepilex Border (Spencer et al., 2016). In one series of 354 patients with chronic leg ulcers who underwent patch testing, 1.4% were allergic to butyl acrylate (Spencer et al., 2016, Valois et al., 2015).

Patch testing for acrylates

Patch testing remains the gold standard of evaluation of potential acrylate sensitivity. Three acrylates are included in the 2019-2020 North American Development Group Standard Allergens: 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate, ethyl acrylate, and methyl methacrylate. The ACDS Core Allergen Series includes four acrylates: hydroxyethyl methacrylate, methyl methacrylate, ethyl acrylate, and ethyl cyanoacrylate. Cyanoacrylates are tested at 10%, methacrylates at 2%, and acrylates at 0.1% to allow for allergic reaction without irritation (Sasseville, 2012). However, screening for cyanoacrylates will not pick up on ACD to Dermabond; it must be tested as is to confirm allergenicity.

Spontaneous polymerization of all acrylates is of concern because this can render the patch-test allergens inert and thus potentially yield false negative results. Spontaneous polymerization can be slowed by petrolatum and storing these allergens in a freezer (Sasseville, 2012).

Less common reactions to acrylates

Acrylates most commonly result in ACD reactions at the site of allergen application. Less common reactions include chemical leukoderma and systemic contact dermatitis. Kwok et al. (2011) reported a unique case of leukoderma after patch testing with an acrylate series in a 53-year-old woman without a history of vitiligo or autoimmune disease in five locations (methyl methacrylate, 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate, 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate, ethyleneglycol dimethacrylate, and ethyl methacrylate).

Another case of interest involved a 28-year-old woman who presented after having her teeth varnished with a product containing 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate. Initially she did not have any local reaction, but she subsequently developed genital dermatitis secondary to feminine hygiene pads. This subsequently resolved, but repeated teeth varnishing resulted in systemic contact dermatitis. The patient was patch tested with positive reactions to multiple acrylates (Sauder and Pratt, 2015).

Conclusions

Acrylates have been used commercially since 1933, and ACD to acrylates is common. Sources of acrylates continue to grow and be reported. Patch testing remains the gold standard in diagnosis of this allergy, but the use of solely standard series may miss clinically relevant acrylates, such as Dermabond and IBOA. We present this review to bring awareness to these allergens and an approach to thinking about them and their sources.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Funding

None.

Study Approval

None.

Financial disclosures

Dr Hylwa is on the Board of Directors of the American Contact Dermatitis Society (unpaid position). Dr Hylwa receives grant funding through WEN and the American Contact Dermatitis Society (unrelated to the current study).

References

- Aerts O., Herman A., Mowitz M., Bruze M., Goossens A. Isobornyl acrylate. Dermatitis. 2020;31(1):4–12. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson T., Bruze M., Gruvberger B., Björkner B. In vivo testing of the protection provided by non-latex gloves against a 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate containing acetone-based dentin-bonding product. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80(6):435–437. doi: 10.1080/000155500300012891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschenbeck K.A., Hylwa S. A diabetic’s allergy ethyl cyanoacrylate in glucose sensor adhesive. Dermatitis. 2017;28(4):289–291. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickers D.R., Lim H.W., Margolis D., Weinstock M.A., Goodman C., Faulkner E. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(3):490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkner B. Plastic materials. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;4:583–621. [Google Scholar]

- Busschots A.M., Meuleman V., Poesen N., Dooms-Goossens A. Contact allergy to components of glue in insulin pump infusion sets. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:205–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1995.tb00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou M., Dhingra N., Strugar T. Contact sensitization to allergens in nail cosmetics. Dermatitis. 2017;28(4):231–240. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde-Salazar L., Vargas I., Tévar E., Barchino L., Heras F. Sensitization to acrylates in varnishes. Dermatitis. 2007;18(1):45–48. doi: 10.2310/6620.2007.06011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darre E., Vedel P., Jensen J.S. Skin protection against methylmethacrylate. Acta Orthop Scand. 1987;58:236–238. doi: 10.3109/17453678709146473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M., Stuart M. Severe allergic contact dermatitis to Dermabond Prineo, a topical skin adhesive of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate increasingly used in surgeries to close wounds. Dermatitis. 2016;27(2):75–76. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKoven J.G., Warshaw E., Zug K.A., Maibach H.I., Belsito D.V., Sasseville D. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2015–2016. Dermatitis. 2018;29(6):297–309. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker A.M., Pratt M.D. Acrylate contact allergy: Patient characteristics and evaluation of screening allergens. Dermatitis. 2011;22:98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunst K.M., Auboeck J., Zahel B., Raffier B., Huemer G.M. Extensive allergic reaction to a new wound closure device (Prineo) Allergy. 2010;65(6):798–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durando D., Porubsky C., Winter S., Kalymon J., O'Keefe T., LaFond A.A. Allergic contact dermatitis to Dermabond (2-octyl cyanoacrylate) after total knee arthroplasty. Dermatitis. 2014;25(2):99–100. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Dars L.D., Chaudhury W., Hughes T.M., Stone N.M. Allergic contact dermatitis to Dermabond after orthopaedic joint replacement. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62(5):315–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2010.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti C., Romita P., Rigano L., Zimerson E., Sicilia M., Ballini A. Isobornyl acrylate: an impurity in alkyl glucosides. Cutan Ocular Toxicol. 2016;35(2):115–119. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2015.1055495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geukens S., Goossens A. Occupational contact allergy to (meth)acrylates. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44(3):153–159. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.044003153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goon A.T., Bruze M., Zimerson E., Goh C.L., Soo-Quee Koh D., Isaksson M. Screening for acrylate/methacrylate allergy in the baseline series: our experience in Sweden and Singapore. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:307–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman A., Aerts O., Baeck M., Bruze M., De Block C., Goossens A. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in Freestyle® Libre, a newly introduced glucose sensor. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77:367–373. doi: 10.1111/cod.12866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hivnor C.M., Hudkins M.L. Allergic contact dermatitis after postsurgical repair with 2-octylcyanoacrylate. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(6):814–815. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.6.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner K., Anderson B. Acrylates. Dermatitis. 2009;20(4):218–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyry H., Liippo J., Virtanen H. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by glucose sensors in type 1 diabetes patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:161–166. doi: 10.1111/cod.13337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamann S., Oppel E., Liu F., Reichl F.X., Heinemann L., Högg C. Evaluation of isobornyl acrylate content in medical devices for diabetes treatment. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019;21(10):533–537. doi: 10.1089/dia.2019.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostner L., Anzengruber F., Guillod C., Recher M., Schmid-Grendelmeier P., Navarini A.A. Allergic contact dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017;37(1):141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok C., Wilkinson M., Sommer S. A rare case of acquired leukoderma following patch testing with an acrylate series. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:292–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loranger C., Alfalah M., Ferrier Le Bouedec M.C., Sasseville D. Alkyl glucosides in contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2017;28(1):5–13. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mine Y., Urakami T., Matsuura D. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate when using the FreeStyle® Libre. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10(5):1382–1384. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muttardi K., White I.R., Banerjee P. The burden of allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylates. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75(3):180–184. doi: 10.1111/cod.12578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppel E., Kamann S., Reichl F.X., Högg C. The Dexcom glucose monitoring system-An isobornyl acrylate-free alternative for diabetic patients. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81(1):32–36. doi: 10.1111/cod.13248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyl J., Dendooven E., Van Eekelen I., den Brinker M., Dotremont H., France A. Prevalence and prevention of contact dermatitis caused by FreeStyle Libre: a monocentric experience. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(4):918–920. doi: 10.2337/dc19-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos L., Cabral R., Gonçalo M. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by acrylates and methacrylates – a 7-year study. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71(2):102–107. doi: 10.1111/cod.12266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasseville D. Acrylates in contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2012;23(1):6–16. doi: 10.1097/DER.0b013e31823d1b81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauder M., Pratt M.D. Acrylate systemic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2015;26(5):235–238. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheman A., Hylwa-Deufel S., Jacob S.E., Katta R., Nedorost S., Warshaw E. Alternatives for allergens in the 2018 American Contact Dermatitis Society core series: report by the American Contact Alternatives Group. Dermatitis. 2019;30(2):87–105. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheman A., Jacob S., Zirwas M., Warshaw E., Nedorost S., Katta R. Contact allergy: alternatives for the 2007 North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) standard screening tray. Dis Mon. 2008;54:7–156. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkawa E., Washio K., Tatsuoka S., Fukunaga A., Sakaguchi K., Nishigori C. A case of contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in FreeStyle Libre: the usefulness of film-forming agents. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81(1):56–57. doi: 10.1111/cod.13239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer A., Gazzani P., Thompson D.A. Acrylate and methacrylate contact allergy and allergic contact disease: a 13-year review. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75(3):157–164. doi: 10.1111/cod.12647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson W.J. Methyl-methacrylate dermatitis. Contact Point. 1941;18:171. [Google Scholar]

- Valois A., Waton J., Avenel-Audran M., Truchetet F., Collet E., Raison-Peyron N. Contact sensitization to modern dressings: a multicentre study on 354 patients with chronic leg ulcers. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;72:90–96. doi: 10.1111/cod.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]