Abstract

In inflammation-associated carcinogenesis, COX-2 is markedly overexpressed, resulting in accumulation of various prostaglandins. 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) is one of the terminal products of COX-2-catalyzed arachidonic acid catabolism with oncogenic potential. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a process by which epithelial cells lose their polarity and adhesiveness, and thereby gain migratory and invasive properties. Treatment of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells with 15d-PGJ2 induced EMT as evidenced by increased expression of Snail and ZEB1, with concurrent down-regulation of E-cadherin. Nuclear extract from 15d-PGJ2-treated MCF-7 cells showed the binding of Snail and ZEB1 to E-box sequences present in the E-cadherin promoter, which accounts for repression of E-catherin expression. Unlike 15d-PGJ2, its non-electrophilic analogue 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 failed to induce EMT, suggesting that the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group located in the cyclopentenone ring of 15d-PGJ2 is essential for its oncogenic function. Notably, the mRNA level of interleukin-8 (IL-8)/CXCL8 was highly elevated in 15d-PGJ2-stimulated MCF-7 cells. 15d-PGJ2-induced up-regulation of IL-8/CXCL8 expression was abrogated by silencing of Snail short interfering RNA. Treatment of normal fibroblast with conditioned medium obtained from cultures of MCF-7 cells undergoing EMT induced the expression of activated fibroblast marker proteins, α-smooth muscle actin and fibroblasts activation protein-α. Co-culture of normal fibroblasts with 15d-PGJ2-stimulated MCF-7 cells also activated normal fibroblast cells to cancer associated fibroblasts. Taken together, above findings suggest that 15d-PGJ2 induces EMT through up-regulation of Snail expression and subsequent production of CXCL8 as a putative activator of fibroblasts, which may contribute to tumor-stroma interaction in inflammatory breast cancer microenvironment.

Keywords: 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2; Breast cancer; Cancer-associated fibroblasts; Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; Tumor microenvironment

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is one of the most common female cancers, predominantly causing carcinoma-associated death in women. The high mortality of breast cancers results from metastasis rather than the primary tumor [1]. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), an underlying process of cancer progression, is a crucial event in initiation of the tumor metastasis [2]. During EMT, cancer cells lose epithelial cell-cell junctions and acquire migratory characteristics to become motile fibroblastic cells with metastatic capacity. E-cadherin, a major adhesion molecule contributing to cell-cell junctions, is highly expressed in epithelium-derived cancer cells. As cancer cells undergo EMT, the expression of E-cadherin is down-regulated [3], whereas levels of proteins expressed in mesenchymal cells are enhanced. The down-regulation of E-cadherin is known to be regulated by repressive transcription factors such as Snail, Slug, and ZEB1, which bind to the E-box present in its promoter region [4].

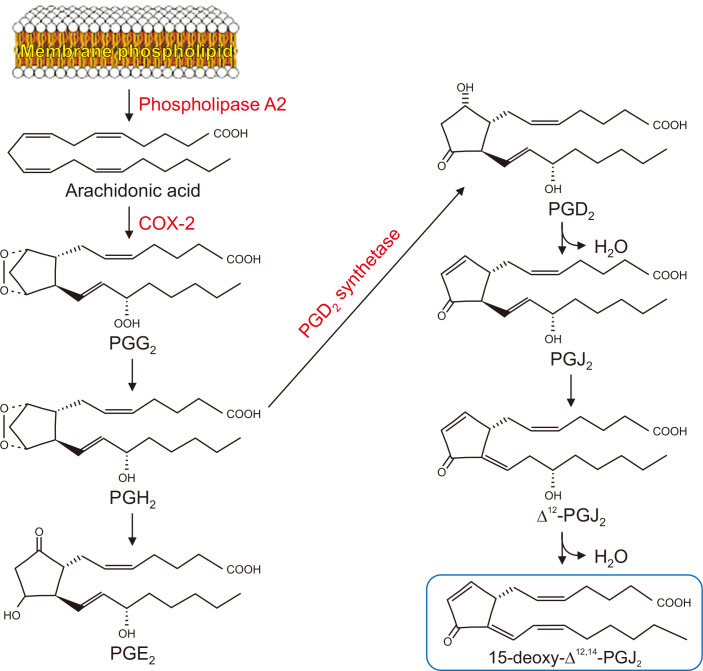

Metastasis of cancer cells is induced by several factors including an inflammatory microenvironment [5]. Aberrant up-regulation of COX-2, a prototypic pro-inflammatory enzyme mediating the biosynthesis of prostaglandins from arachidonic acid, is associated with the progression of breast cancer [6]. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2), a cyclopentenone prostaglandin, is one of the final products of the COX-2-dependent arachidonic acid pathway (Fig. 1) [7]. Although 15d-PGJ2 has been shown to have anti-carcinogenic roles [8], it also promotes tumor development, such as cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis [9]. 15d-PGJ2 contains an electrophilic α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group in its cyclopentenone ring, which may play a crucial role in exerting pro- or anti-carcinogenic effects.

Figure 1. Biosynthesis of PGE2 and 15d-PGJ2, two principal prostaglandins involved in inflammation and cancer.

PGG2, prostaglandin G2; PGH2, prostaglandin H2; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PGD2, prostaglandin D2; PGJ2, prostaglandin J2.

During the progression of cancer, the tumor microenvironment plays a pivotal role by providing the field for cancer and stromal cells for interaction [10]. Among the components of the tumor stroma including extracellular matrix, inflammatory cells and fibroblasts, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) represent major units [11]. CAFs, equated to activated fibroblasts or myofibroblasts, assist tumor development by secreting various cytokines, growth factors, and matrix-degrading enzymes, which stimulate cancer cells for proliferation and progression [12]. Origins of CAFs have been proposed by some studies [13], but the mechanisms by which fibroblasts are activated still elusive. The alteration of normal fibroblasts to CAFs is affected by a number of factors, especially through the crosstalk between fibroblasts and cancer cells. Not only cancer cells activate fibroblasts to CAFs, but activated fibroblasts also stimulate cancer cells to become more invasive and carcinogenic.

In the present study, we investigated the effect of 15d-PGJ2 on manifestation of an EMT phenotypes in human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells, and whether this could activate fibroblasts to CAFs, consequently affecting the overall cancer progression and metastasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

15d-PGJ2, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 were obtained from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). MTT was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). RPMI 1640 medium, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), and FBS were purchased from Gibco BRL (Grand Island, NY, USA). Antibody against E-cadherin was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Antibodies against Snail and fibroblasts activation protein-α (FAP-α) were products of Santa Cruz Biotechnolgies Co. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibody for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). The antibody used for neutralization of interleukin-8 (IL-8) was purchased from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Secondary antibodies, Snail short interfering RNA (siRNA), negative control siRNA, and lipofectamin RNAi-MAX reagent were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc. (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All other chemicals used were of analytical or the highest purity grade available.

Cell culture

MCF-7 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and a 100 ng/mL penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone mixture at 37℃ in humidify atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. Normal fibroblasts were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and an 100 ng/mL penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone mixture at 37℃ in humidify atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. The cells were plated at an appropriate density according to each experimental scale.

Co-culture of fibroblasts with cancer cells

Human breast fibroblasts were plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL on a 6-well plate in DMEM medium, and 1 × 106 cells/mL of MCF-7 cells were seeded on the membrane of transwell insert (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) in RPMI medium. After 24-hour incubation, MCF-7 cells were treated with 15d-PGJ2 or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Cell proliferation assay

Human breast fibroblasts were plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL in 48-well plate and were treated with the conditioned medium of MCF-7 cells for 24 hours. The proliferation rate was determined by the conventional MTT assay. After incubation, cells were treated with the MTT solution (final concentration, 1 mg/mL) for 1 hour at 37℃. The dark blue formazan crystals that formed in intact cells were solubilized in DMSO, and the absorbance at 570 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Preparation of nuclear extracts

After treatment with 15d-PGJ2 or DMSO, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, scraped in 1 mL PBS and centrifuged at 7,000 ×g for 15 minutes at 4℃. Pellets were suspended in 50 μL of hypotonic buffer A (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]) for 15 minutes on ice, and 1 μL of 10 Nonidet P-40 solution was added for 5 minutes. The mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 7 minutes. The pellets were washed with hypotonic buffer and were resuspended in hypertonic buffer C (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 20% glycerol, 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF) for 30 minutes on ice and centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 7 minutes. The supernatant containing nuclear proteins was collected and stored at –70℃ after determination of the protein concentration by the Bradford method using the protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from MCF-7 cells and normal fibroblasts using the TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. One μl of total RNA was reverse transcribed with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) at 42℃ for 50 minutes and at 72℃ for 15 minutes. The primers used are listed in Appendix.

Western blot analysis

MCF-7 cells (2 × 105 cells/mL) were plated in a 60-mm dish and treated with 15d-PGJ2 under specified conditions. After rinsing with PBS, the cells were exposed to radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and a protease inhibitor in ice for 30 minutes. After centrifugation at 12,000 ×g for 15 minutes, the supernatant was collected and stored at –70℃ until use. The protein concentration was determined by using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Protein samples were electrophoresed on 8% to 10% SDS PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane at 300 mA for 3 hours. Blots were incubated in fresh blocking buffer (0.1% Tween-20 in TBS containing 5% non-fat dry milk, pH 7.4) for 1 hour followed by incubation with appropriate primary antibodies in TBS with Tween-20 (TBST) with 3% non-fat dry milk. After washing with TBST three times, blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody in TBST with 3% non-fat dry milk for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were washed again three times with TBST buffer, and were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Immunocytochemistry of Snail and E-cadherin

To visualize the expression of Snail and E-cadherin, immunocytochemistry was performed. MCF-7 cells were plated on the chamber slide at a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL and treated with 15d-PGJ2 or DMSO. Cells were fixed with 95% methanol/5% acetic acid at –20℃ for 5 minutes, washed with PBS twice, treated with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 minutes, washed with PBS with Tween-20 (PBST), and then washed with PBS. Samples were incubated with blocking agent (0.1% Tween-20 in PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin [BSA]) at room temperature for 1 hour, washed with PBS, and then incubated with a diluted (1 : 100) primary antibody for overnight at 4℃. After washing with PBS, samples were incubated with a diluted (1 : 1,000) TRITC-conjugated anti-mouse or FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G secondary antibody in PBST containing 1% BSA at room temperature for 1 hour. Samples were washed with 0.1% PBST containing 1% BSA then examined under a fluorescent microscope.

Cell-scattering assay

MCF-7 cells were plated at a density of 5 × 104 cells/mL in a 6-well plate and treated with 15d-PGJ2 or DMSO. Cells were observed for 5 days, and the scattering cells were examined under a confocal microscope.

Cell migration assay

Normal fibroblasts were plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL in a 12-well plate with culture inserts (ibidi). After 24-hour incubation, culture inserts were removed with sterilized forceps and cells were treated with the conditioned medium of 15d-PGJ2 or DMSO-treated MCF-7 cells. Cells were observed over 24 to 48 hours under a confocal microscope.

Transient transfection with Snail siRNA

MCF-7 cells were seeded at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells in 60 mm dish and grown to 80% confluence. Snail siRNA (10 nM) was transfected into MCF-7 cells with lipofectamine RNAi-MAX reagents according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48-hour transfection, cells were treated with 15d-PGJ2 for additional 12 hours, and total RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed by RT-PCR. The target sequence for Snail siRNA was 5’-GCGAGCUGCAGGACUCUAA-3’ (forward) and 5’-AGGACUCUAAUCCAGAGUU-3’ (reverse).

Statistical analysis

When necessary, data were expressed as means ± SD of at least three independent experiments, and statistical analysis for single comparison was performed using the Student’s t-test.

RESULTS

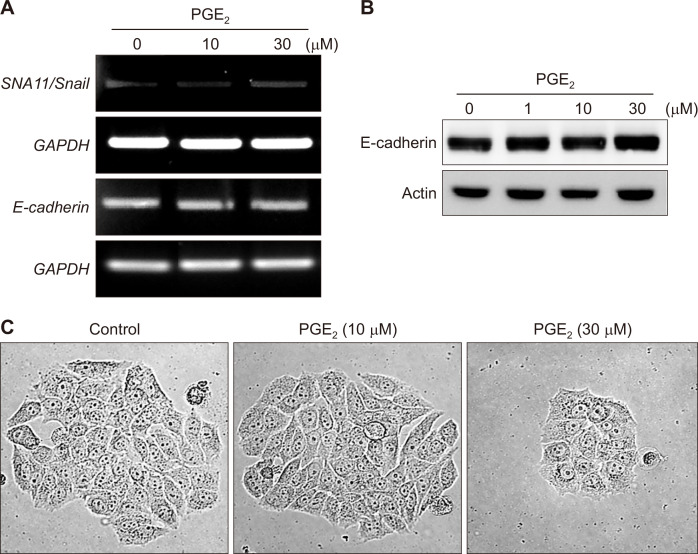

PGE2 does not induce EMT of MCF-7 cells

One of the major products of the arachidonic acid cascade is PGE2 (Fig. 1). Previous studies have demonstrated that PGE2 induces EMT in gastric cancer (SNU719) [14] and lung cancer (A549) cells [15]. To determine whether PGE2 also induces EMT in human breast cancer cells, MCF-7 cells were treated with PGE2. The mRNA level of Snail, a principal transcription factor involved in EMT, was unchanged (Fig. 2A). The expression of E-cadherin at both transcriptional (Fig. 2A) and translational (Fig. 2B) levels was not also influenced by the same treatment. Moreover, the morphology of PGE2-treated MCF-7 cells was not much different from that of the control, growing in contact with the neighboring cells (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that PGE2 lacks ability to induce EMT in MCF-7 cells.

Figure 2. The effects of PGE2 on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells.

(A, B) MCF-7 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of PGE2 for 12 hours. Cells were incubated for 12 hours and 24 hours to measure mRNA (A) and/or protein (B) levels of Snail and E-cadherin by reverse transcriptase-PCR and Western blot analysis, respectively. (C) MCF-7 cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of PGE2 for 24 hours, and the cell-scattering assay was performed (× 100). Scattering cells were photographed under an inverted microscope. PGE2, prostaglandin E2; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

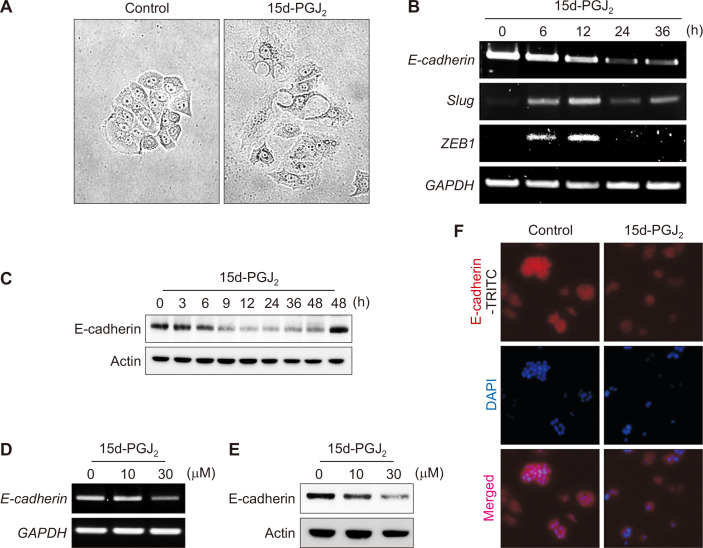

15d-PGJ2 induces manifestation of an EMT phenotype in MCF-7 cells

As 15d-PGJ2 is a terminal product of the alternative arachidonic acid pathway, we examined its effects on EMT. 15d-PGJ2 treatment resulted in the scattering of MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3A), indicating that the cells acquired the migratory characteristics of mesenchymal cells. 15d-PGJ2 also induced a transient increase in the expression of repressive transcription factors, Slug and ZEB1 (Fig. 3B). Consequent down-regulation of E-cadherin was observed at both mRNA (Fig. 3B) and protein (Fig. 3C) levels in time- (Fig. 3B and 3C) and concentration- (Fig. 3D and 3E) dependent manners. In addition, the decreased expression of E-cadherin was verified by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3. 15d-PGJ2-induced EMT of phenotypes MCF-7 cells.

(A) MCF-7 cells were incubated with 30 μM of 15d-PGJ2 for 24 hours (× 100). The scattering growth pattern was assessed by the cell-scatting assay. (B, C) MCF-7 cells were incubated with 30 μM of 15d-PGJ2 for the indicated time periods. The mRNA (B) and protein (C) levels of EMT-related factors were determined by reverse transcriptase-PCR and Western blot analysis, respectively. (D, E) MCF-7 cells were incubated with 10 or 30 μM of 15d-PGJ2 for 12 or 24 hours to measure the mRNA (D) and protein (E) levels of E-catherin, respectively. (F) Immunocytochemical analysis was performed using E-cadherin antibody after treatment of MCF-7 cells with 15d-PGJ2 for 12 hours (× 40). Cells were stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) and visualized under a confocal microscopy. 15d-PGJ2, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

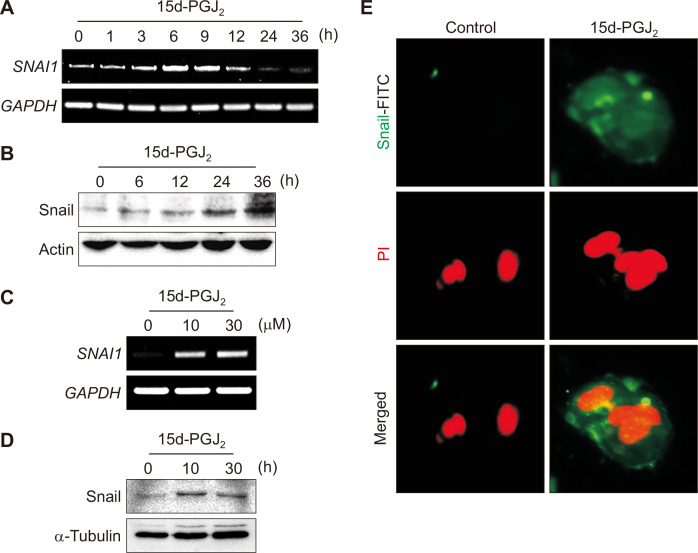

While E-cadherin expression was down-regulated, the expression of Snail was elevated at both transcriptional and translational levels in time- (Fig. 4A and 4B) and concentration-dependent (Fig. 4C and 4D) manners in 15d-PGJ2-treated MCF-7 cells. The 15d-PGJ2-induced accumulation of Snail was also visualized by immunofluorescence staining of MCF-7 cells (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4. Effects of 15d-PGJ2 on Snail expression in MCF-7 cells.

(A, B) MCF-7 cells were incubated with 30 μM of 15d-PGJ2 for the indicated time periods. The mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels of snail were determined by reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR and Western blot analysis, respectively. (C) MCF-7 cells were incubated with 10 or 30 μM of 15d-PGJ2 for 6 hours, and the mRNA expression SNAI1/Snail was determined by RT-PCR. (D) MCF-7 cells were incubated with 30 μM of 15d-PGJ2 for 6 or 12 hours, and the nuclear levels of Snail were measured by Western blot analysis. (E) Immunocytochemical analysis was performed using E-cadherin antibody after treatment of MCF-7 cells with 15d-PGJ2 for 12 hours (× 100). Cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and visualized under a confocal microscopy. 15d-PGJ2, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

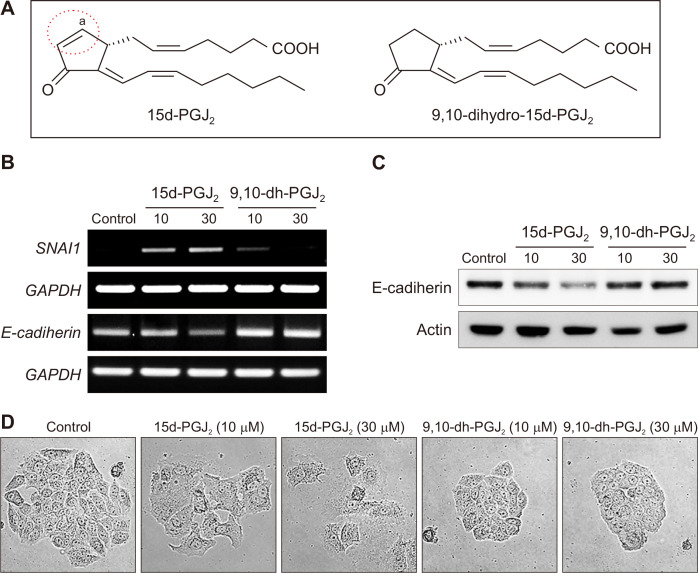

The cyclopentenone ring structure of 15d-PGJ2 is critical in inducing EMT in MCF-7 cells

An α,β-unsaturated carbonyl moiety of cyclopentenone prostaglandins including 15d-PGJ2 is considered to account for some distinct biological reactions they mediate. 9,10-Dihydro-15d-PGJ2, a non–electrophilic analogue of 15d-PGJ2, lacks such a reactive α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group in its cyclopentenone ring (Fig. 5A). In contrast to 15d-PGJ2, 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 failed to influence the expression of Snail and E-cadherin (Fig. 5B and 5C). In addition, 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2-treated MCF-7 cells grew in contact with the neighboring cells, whereas MCF-7 cells dispersed in response to the same concentration of 15d-PGJ2 (Fig. 5D). These results imply that the electrophilic carbon center in the cyclopentenone ring of 15d-PGJ2 is critical for inducing EMT in MCF-7 cells.

Figure 5. A critical role of the cyclopentenone ring in 15d-PGJ2-induced EMT in MCF-7 cells.

(A) 15d-PGJ2 contains a cyclopentenone ring structure with an electrophilic α,β-unsaturated carbonyl moiety, which is absent in 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2. (B, C) MCF-7 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of 15d-PGJ2 or 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2. Cells were incubated for 12 hours and 24 hours to measure the mRNA (B) and protein (C) levels of Snail and/or E-cadherin, respectively. (D) MCF-7 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of 15d-PGJ2 or 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2 for 24 hours (× 100). Scattering morphology was assessed by the cell-scattering assay. 15d-PGJ2, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2; 9,10-dh-PGJ2, 9,10-dihydro-15d-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. aIt denotes an electrophilic carbon center.

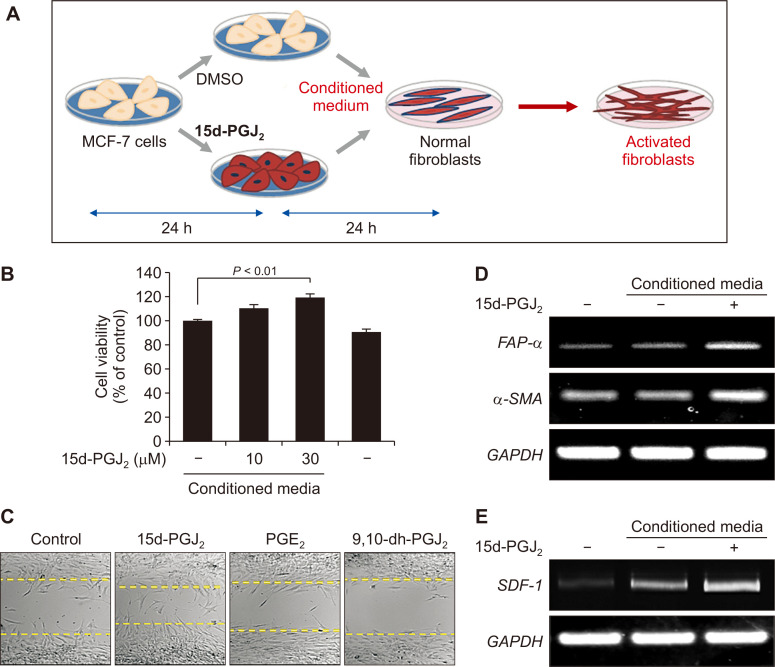

MCF-7 cells activate human breast fibroblasts to CAFs

Fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment are proposed to be in the activated state and are termed CAFs. CAFs tend to gain increased motility and proliferation, with enhanced expression of α-SMA, FAP-α, and stromal-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), also known as CXCL12, which are regarded as the markers of CAFs [16]. To elucidate the effect of MCF-7 cells on the activation of human breast fibroblasts, the conditioned medium of MCF-7 cells was collected after 24 hours of incubation (Fig. 6A). When exposed to the conditioned medium of MCF-7 cells treated with 15d-PGJ2, the viability of fibroblasts was enhanced (Fig. 6B). In another experiment, proliferative capability of fibroblasts was assessed by the cell migration assay. The conditioned media of PGE2 and 9,10-dihydro-15d-PGJ2-treated-MCF-7 cells did not stimulate fibroblasts to migrate, whereas fibroblasts incubated with the conditioned medium of 15d-PGJ2-treated-MCF-7 cells gained the increased migration potential as evidenced by a significantly reduced gap (Fig. 6C). Moreover, to determine whether fibroblasts were transformed to CAFs, we measured the mRNA levels of α-SMA, FAPα, and SDF-1. As a result, transcriptional expression of CAF markers was up-regulated in normal breast fibroblasts treated with conditioned medium of 15d-PGJ2-stimulated MCF-7 cells (Fig. 6D and 6E). Taken together, these findings indicate that the activation of human breast fibroblasts to CAFs is influenced by breast cancer cells undergoing EMT.

Figure 6. The effect of conditioned medium from MCF-7 cells on the proliferation and activation of human breast fibroblasts.

(A, B) Human breast fibroblasts were exposed to the conditioned media of MCF-7 cells (A) treated with the indicated concentrations of 15d-PGJ2 for 24 hours (B). The cell proliferation rate was determined by the MTT assay, and presented as means ± SD (n = 3). (C) Human breast fibroblasts were incubated in the 24 hour-conditioned medium of MCF-7 cells treated with 10 mM of the indicated prostaglandins (× 100). Cell migration was visualized over 24 to 48 hours under a confocal microscope. (D, E) Human breast fibroblasts were treated with the conditioned medium of MCF-7 cells treated with DMSO or 15d-PGJ2 (30 μM). The mRNA levels of FAP-α, α-SMA (D) and the secretion factor SDF-1 (E) were determined by RT-PCR. 15d-PGJ2, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; FAP-α, fibroblasts activation protein-α; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; SDF-1, stromal-derived factor-1.

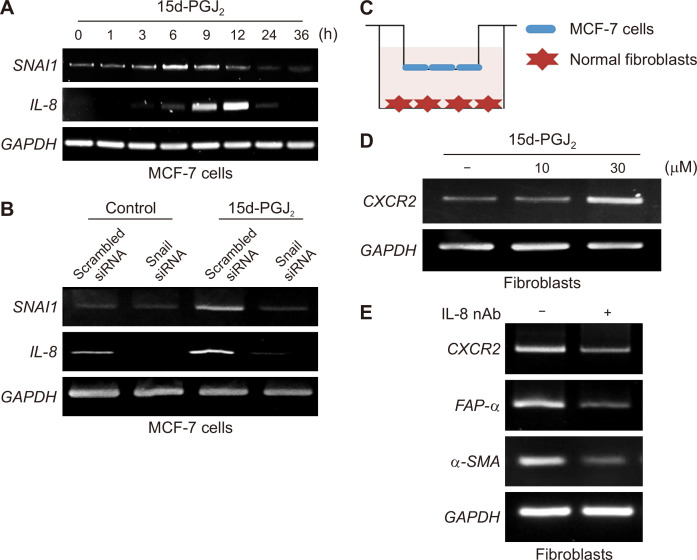

Secretion factors from MCF-7 cells may play a role in activating fibroblasts to CAFs; IL-8 as a putative mediator

Based on the above results, we speculated that certain secreted factors could be responsible for the crosstalk between breast cancer cells and fibroblasts. IL-8/CXCL8 is known to play an important role in EMT and the tumor microenvironment [17]. To investigate the possible factors involved in the tumor-stroma interactions, expression of IL-8 as well as SNAI1 was measured in 15d-PGJ2-treated MCF-7 cells by RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 7A, the mRNA level of SNAI1 started to increase at 6 hours after 15d-PGJ2 treatment which was accompanied by induced IL-6 expression. To determine whether IL-8 is a key regulator in 15d-PGJ2-induced EMT phenomenon, MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected with scrambled or Snail siRNA, and treated with DMSO or 15d-PGJ2. Knock down of Snail resulted in suppression of IL-8 expression (Fig. 7B). These findings suggest that IL-8 may be a putative mediator connecting EMT of MCF cells and fibroblasts. Chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2), an IL-8 receptor, was up-regulated in the fibroblasts co-cultured with MCF-7 cells stimulated with 15d-PGJ2 (Fig. 7C and 7D). The expression of CXCR2 as well as FAP-α in activated fibroblasts stimulated with conditioned media from 15d-PGJ2-treated MCF-7 cells was abrogated in the presence of IL-8 neutralizing antibody (Fig. 7E). It is hence likely that fibroblasts stimulated in response to IL-8 express a higher level of its receptor, CXCR2.

Figure 7. Up-regulated expression of IL-8 and its involvement in 15d-PGJ2-induced EMT and activation of fibroblasts.

(A) MCF-7 cells were treated with DMSO or 30 μM of 15d-PGJ2 for the indicated time periods. The mRNA levels of IL-8 and Snail were determined by reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR. (B) MCF-7 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA as a negative control or Snail siRNA for 48 hours and exposed to DMSO or 15d-PGJ2 (30 μM) for another 12 hours. The mRNA levels of Snail and IL-8 were determined by RT-PCR. (C) For the transwell co-culture assay, human breast cancer MCF-7 cells stimulated with 15d-PGJ2 (10 or 30 μM) for 24 hours and fibroblasts were seeded in the upper and the lower chambers, respectively. (D) After 24-hour co-culture, the mRNA level of CXCR2 expressed in fibroblasts was determined by RT-PCR. (E) The expression of CXCR2 as well as cancer-associated fibroblast marker genes was measured in human breast fibroblasts incubated with conditioned media derived from 15d-PGJ2-stimulated MCF-7 cells in the absence or presence of IL-8 neutralizing antibody (IL-8 nAb; 10 μL/mL). IL-8, interleukin-8; 15d-PGJ2, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; siRNA, short interfering RNA; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; CXCR2, chemokine receptor 2; FAP-α, fibroblasts activation protein-α α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin.

DISCUSSION

Abnormal up-regulation of COX-2 contributes to the chronic inflammation, which is closely related to the tumor progression [18]. In breast carcinogenesis, overexpression of COX-2 has been frequently associated with poor prognosis, including cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis [19,20]. In the light of the fact that the high mortality of human breast cancer appears to be primarily caused by metastasis, it would be worth examining the initiation of metastasis in depth. EMT is considered to be an important means for cancer cells to escape the tissue structure and migrate to other organs [21]. Tumor microenvironment plays a vital role in growth and survival of cancer cells and also in metastasis. As a major product of COX-2, PGE2 has been reported to play a crucial role in the inflammatory tumor microenvironment and in EMT of gastric cancer (SNU719) [14] and lung cancer (A549) cells [15]. Therefore we initially speculated that PGE2 might also cause EMT in breast cancer cells. Contrary to our speculation, however, PGE2 did not induce EMT of human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells. It has been shown that the level of PGE2 is different between the central and peripheral regions of colorectal cancer [22]. Similarly, the function of PGE2 may also differ depending on its subcellular localization. This may explain why the EMT-inducing effect of PGE2 was not prominent in breast cancer cells unlike in gastric and lung cancer cells.

15d-PGJ2, another lipid mediator produced during inflammation, is one of the terminal products in the COX-2-mediated arachidonic acid pathway [23]. 15d-PGJ2 is known to exert dual roles in carcinogenesis depending on the cell type and its intracellular concentration [24]. The present study focused on the oncogenic effect of 15d-PGJ2 in inducing EMT in human breast malignancies. E-cadherin is down-regulated by suppressive transcription factors such as Snail, Slug and ZEB1, and then cancer cells undergoing EMT subsequently lose cell-cell adhesion [25]. The data from the present study reveal that 15d-PGJ2 up-regulates expression of EMT-related transcription factors, thereby suppressing the transcription of E-cadherin. The underlying molecular mechanism by which 15d-PGJ2 enhances the expression of Snail remains to be unveiled.

Tumor progression, which involves tumor growth, angiogenesis, and EMT, significantly relies on the microenvironment surrounding the tumor [26]. One study demonstrates that stromal cells such as fibroblasts play an essential role in the metastasis of breast cancer cells [27]. Stromal fibroblasts around the tumor termed CAFs are activated fibroblasts and are reported to secrete tumor promoting signaling molecules [28]. Although the significance of CAFs has been acknowledged, their origins and characteristics are yet to be clearly defined.

Multiple sources of CAFs have been suggested by several studies, including the conversion of normal fibroblasts [26], bone marrow progenitor cells [29], epithelial cancer cells or endothelial cells [30]. The present study demonstrates the generation of CAFs as a consequence of activation of normal fibroblast by cancer cell-derived secretion factors. Increased expression of α-SMA and FAP-α in fibroblasts is commonly regarded as the characteristics of CAFs. However, some studies suggest that this is not necessarily same for all CAFs [31], while another study reports SDF-1 as a representative marker of CAFs [16]. The data from our present study indicate that human breast fibroblasts are activated by the conditioned medium of 15d-PGJ2-treated MCF-7 cells, with enhanced expression of α-SMA, FAP-α and SDF-1. Based on these results, it could be speculated that certain factors may be involved in the interaction between cancer cells and fibroblasts.

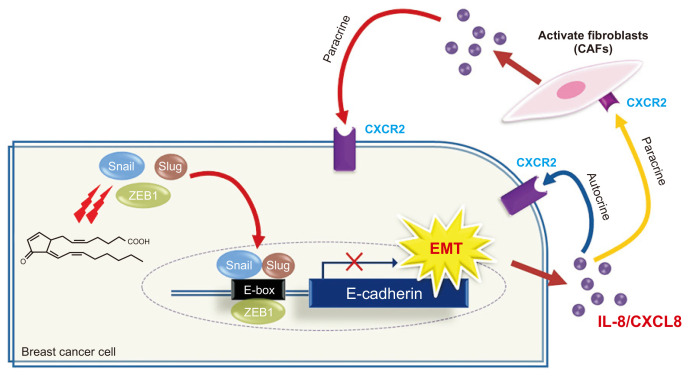

Among cytokines/chemokines screened in 15d-PGJ2-treated-MCF-7 cells, IL-8 appears to be the most plausible mediator, based on the time and the level of induction of the EMT-related genes. Corresponding to the elevated IL-8 expression, expression of CXCR2 which is IL-8 receptor B was also induced in fibroblasts. This suggests that fibroblasts become activated in response to IL-8 secretion by breast cancer cells. IL-8 also has been reported to be secreted by CAFs [32], indicative of the existence of both autocrine and paracrine routes of IL-8 (Fig. 8) that may influence the fibroblast activation through a positive feedback mechanism. Further investigations would be needed to clarify the involvement of other cytokines in tumor-stroma interaction.

Figure 8. Proposed mechanisms for 15d-PGJ2-induced EMT in MCF-7 cells and consequent activation of human breast fibroblasts.

15d-PGJ2, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; CXCR2, chemokine receptor 2; IL-8, interleukin-8.

In summary, this study reveals for the first time that the cyclopentenone prostaglandin 15d-PGJ2 produced during chronic inflammation can cause EMT of MCF-7 cells through up-regulation of Snail expression. MCF-7 cells going through EMT secrete various factors to interact with stromal cells, in which IL-8 may play a central role in the activation of human breast fibroblasts into CAFs. Such crosstalk between MCF-7 cells and adjacent fibroblasts, as a prelude to breast cancer metastasis, merits further investigations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Global Core Research Center (GCRC) grant (No. 2011-0030001) from the National Research Foundation, Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Sporn MB. The war on cancer. Lancet. 1996;347:1377–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalluri R. EMT: when epithelial cells decide to become mesenchymal-like cells. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1417–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI39675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maeda M, Johnson KR, Wheelock MJ. Cadherin switching: essential for behavioral but not morphological changes during an epithelium-to-mesenchyme transition. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 5):873–87. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulte J, Weidig M, Balzer P, Richter P, Franz M, Junker K, et al. Expression of the E-cadherin repressors Snail, Slug and Zeb1 in urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder: relation to stromal fibroblast activation and invasive behaviour of carcinoma cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2012;138:847–60. doi: 10.1007/s00418-012-0998-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dannenberg AJ, Howe LR. The role of COX-2 in breast and cervical cancer. Prog Exp Tumor Res. 2003;37:90–106. doi: 10.1159/000071368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scher JU, Pillinger MH. 15d-PGJ2: the anti-inflammatory prostaglandin? Clin Immunol. 2005;114:100–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin SW, Seo CY, Han H, Han JY, Jeong JS, Kwak JY, et al. 15d-PGJ2 induces apoptosis by reactive oxygen species-mediated inactivation of Akt in leukemia and colorectal cancer cells and shows in vivo antitumor activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5414–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surh YJ, Na HK, Park JM, Lee HN, Kim W, Yoon IS, et al. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2, an electrophilic lipid mediator of anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:1335–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.07.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Littlepage LE, Egeblad M, Werb Z. Coevolution of cancer and stromal cellular responses. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:499–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhowmick NA, Neilson EG, Moses HL. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature. 2004;432:332–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Micke P, Ostman A. Exploring the tumour environment: cancer-associated fibroblasts as targets in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2005;9:1217–33. doi: 10.1517/14728222.9.6.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xing F, Saidou J, Watabe K. Cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in tumor microenvironment. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2010;15:166–79. doi: 10.2741/3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jee YS, Jang TJ, Jung KH. Prostaglandin E2 and interleukin-1β reduce E-cadherin expression by enhancing snail expression in gastric cancer cells. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:987–92. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.9.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dohadwala M, Yang SC, Luo J, Sharma S, Batra RK, Huang M, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-dependent regulation of E-cadherin: prostaglandin E2 induces transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and snail in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5338–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mishra PJ, Mishra PJ, Humeniuk R, Medina DJ, Alexe G, Mesirov JP, et al. Carcinoma-associated fibroblast-like differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4331–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palena C, Hamilton DH, Fernando RI. Influence of IL-8 on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and the tumor microenvironment. Future Oncol. 2012;8:713–22. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kundu JK, Surh YJ. Inflammation: gearing the journey to cancer. Mutat Res. 2008;659:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies G, Salter J, Hills M, Martin LA, Sacks N, Dowsett M. Correlation between cyclooxygenase-2 expression and angiogenesis in human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2651–6. doi: 10.3390/cancers12082008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranger GS, Thomas V, Jewell A, Mokbel K. Elevated cyclooxygenase-2 expression correlates with distant metastases in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:2349–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hugo H, Ackland ML, Blick T, Lawrence MG, Clements JA, Williams ED, et al. Epithelial--mesenchymal and mesenchymal--epithelial transitions in carcinoma progression. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:374–83. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young AL, Chalmers CR, Hawcroft G, Perry SL, Treanor D, Toogood GJ, et al. Regional differences in prostaglandin E2 metabolism in human colorectal cancer liver metastases. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Na HK, Surh YJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) ligands as bifunctional regulators of cell proliferation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1381–91. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00488-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim EH, Surh YJ. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 as a potential endogenous regulator of redox-sensitive transcription factors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1516–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreno-Bueno G, Portillo F, Cano A. Transcriptional regulation of cell polarity in EMT and cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:6958–69. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Delaunay T, Naeem R, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, Sullivan A, Brooks MW, Bell GW, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557–63. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serini G, Gabbiani G. Mechanisms of myofibroblast activity and phenotypic modulation. Exp Cell Res. 1999;250:273–83. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Direkze NC, Hodivala-Dilke K, Jeffery R, Hunt T, Poulsom R, Oukrif D, et al. Bone marrow contribution to tumor-associated myofibroblasts and fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8492–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Wever O, Demetter P, Mareel M, Bracke M. Stromal myofibroblasts are drivers of invasive cancer growth. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2229–38. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugimoto H, Mundel TM, Kieran MW, Kalluri R. Identification of fibroblast heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1640–6. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.12.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li L, Dragulev B, Zigrino P, Mauch C, Fox JW. The invasive potential of human melanoma cell lines correlates with their ability to alter fibroblast gene expression in vitro and the stromal microenvironment in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1796–804. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]