Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The goal of this study is to examine cross-sectional rates of use and longitudinal pathways of hookah use among U.S. youth (ages 12–17), young adults (ages 18–24), and adults 25+ (ages 25 and older).

DESIGN

Data were drawn from the first three waves (2013–2016) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study, a nationally representative, longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adults and youth. Respondents with data at all three waves (youth, N = 11,046; young adults, N = 6,478; adults 25+, N = 17,188) were included in longitudinal analyses.

RESULTS

Young adults had higher ever, past 12-month (P12M), and past 30-day cross-sectional prevalence of hookah use at each wave than youth or adults 25+. The majority of Wave 1 (W1) hookah users were P12M users of other tobacco products (youth: 73.9%, young adults: 80.5%, adults 25+: 83.2%). Most youth and adult W1 P12M hookah users discontinued use in Waves 2 or 3 (youth: 58.0%, young adults: 47.5%, adults 25+: 63.4%). Most W1 P12M hookah polytobacco users used cigarettes (youth: 49.4%, young adults: 59.4%, adults 25+: 63.2%) and had lower rates of quitting all tobacco than exclusive hookah users or hookah polytobacco users who did not use cigarettes.

CONCLUSIONS

Hookah use is more common among young adults than among youth or adults 25+. Discontinuing hookah use is the most common pathway among exclusive or polytobacco hookah users. Understanding longitudinal transitions in hookah use is important in understanding behavioral outcomes at the population level.

INTRODUCTION

Hookah (also known as waterpipe, narghile, argileh, hubble-bubble, or goza) is a combusted tobacco product that typically uses charcoal to heat flavored tobacco and is often smoked in group settings.1 Hookah was the second most popular tobacco product used by U.S. youth and young adults between 2013 and 2014.2,3 Hookah smoke exposes users to nicotine and contains more of the same toxic chemicals as other combusted tobacco products.4,5

National studies have shown that past 30-day (P30D) hookah use among high school students increased from 4.1% to 9.4% between 2011 and 20146 but has since decreased to 4.1% in 2018.7 National estimates of current hookah smoking among young adults increased from 2.5% in 2012 to 3.2% by in 2014.8,9 The proliferation of hookah cafés and bars, particularly around college campuses, is likely a contributing factor in the increased prevalence of use among young adults.10–12 While hookah use is popular among youth and young adults, it is not limited to this population. Published data from the Tobacco Products and Risk Perceptions Surveys found that in 2014–2015, prevalence of ever and P30D hookah smoking among U.S. adults was 15.8% and 1.5%, respectively,13 and 0.6% of adults used hookah every day or some days as reported by the National Health Interview Survey, 2013–2014.8

One of the most salient aspects among hookah users is the concomitant use of other tobacco products, or polytobacco use.1 Based on 2014–2015 data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, 9.7 % of US young adults and 1.0% of US adults 25+ used hookah plus at least one other tobacco product.14 One study among college students showed almost 30% of hookah users also used cigarettes in the past 30 days,12 while another study showed almost half (48.6%) of current hookah users also smoked cigarettes.15 Additionally, among U.S. high school seniors, occasional and regular cigarette smokers were four and five times more likely to use hookah than nonsmokers, respectively.16

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration now regulates manufacturing, packaging, labeling, advertising, sales, and distribution of all tobacco products including hookah tobacco under the Deeming Rule that went into effect in August 2016.13,17 The current hookah literature is limited to either cross-sectional national studies or studies based on convenience samples of college students.12,13 Despite the pervasive belief that hookah use is less harmful than smoking cigarettes, hookah smoking has been associated with increased health risks similar to those from other combustible tobacco products and additional risks such as carbon monoxide poisoning.18–23 With rising prevalence among youth and young adults, large-scale longitudinal studies at a population level of patterns of hookah use are useful to inform tobacco control interventions and tobacco regulations.24–26

This study expands the current evidence base using the PATH Study to explore longitudinal pathways of hookah use across three waves of data from 2013 to 2016. The first aim of this study is to examine differences between each of the first three waves of cross-sectional weighted estimates of ever, past 12-month (P12M), P30D, and daily P30D hookah use for U.S. youth (ages 12–17), young adults (ages 18–24), and adults 25+ (ages 25 and older) (Aim 1). Using the three-wave longitudinal within-person data from the PATH Study, the second aim of this study is to examine age group differences in Wave 1 (W1), Wave 2 (W2), and Wave 3 (W3) pathways of persistent use, discontinued use, and reuptake of hookah among W1 P12M hookah users (Aim 2). Additionally, this study compares longitudinal transitions of use among W1 exclusive hookah users, W1 hookah users who use multiple tobacco products including cigarettes, and W1 hookah users who use multiple tobacco products not including cigarettes to understand product transitions such as persistent use, discontinued use and product switching (Aim 3). This study fills knowledge gaps by assessing longitudinal transitions for exclusive and polytobacco hookah use separately, a useful component in understanding population-level tobacco use behavioral patterns that could help inform hookah-related regulations.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

The PATH Study is an ongoing, nationally representative, longitudinal cohort study of youth (ages 12–17) and adults (ages 18 and older) in the U.S. Self-reported data were collected using audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) administered in English and Spanish. Further details regarding the PATH Study design and W1 methods are published elsewhere.27,28 At W1, the weighted response rate for the household screener was 54.0%. Among screened households, the overall weighted response rate was 78.4% for youth and 74.0% for adults at W1, 87.3% for youth and 83.2% for adults at W2, and 83.3% for youth and 78.4% for adults at W3. Details on survey interview procedures, questionnaires, sampling, and weighting and information on accessing the data are available at https://doi.org/10.3886/Series606. The study was conducted by Westat and approved by the Westat Institutional Review Board. All participants ages 18 and older provided informed consent, with youth participants ages 12 to 17 providing assent while their parent/legal guardian provided consent.

The current study reports cross-sectional estimates from 13,651 youth and 32,320 adults who participated in W1 (data collected September 12, 2013 through December 14, 2014), 12,172 youth and 28,362 adults at W2 (October 23, 2014 through October 30, 2015), and 11,814 youth and 28,148 adults at W3 (October 19, 2015 to October 23, 2016). The differences in the number of completed interviews between W1, W2, and W3 reflect attrition due to nonresponse, mortality, and other factors, as well as youth who enroll in the study at W2 or W3.27 We also report longitudinal estimates from W1 youth (N = 11,046), W1 young adults (N = 6,478), and W1 adults 25+ (N = 17,188) with data collected at all three waves. See Supplemental Figure 1 for a detailed description of the analytic sample for longitudinal analysis.

Measures

Tobacco use

At each wave, adults and youth were asked about their tobacco use behaviors for cigarettes, electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), traditional cigars, cigarillos, filtered cigars, pipe tobacco, hookah, snus pouches and other smokeless tobacco (i.e., loose snus, moist snuff, dip, spit, or chewing tobacco), and dissolvable tobacco. Participants were asked about P30D use of “e-cigarettes” at W1 and W2 and “e-products” (e-cigarettes, e-cigars, e-pipes, and e-hookah) at W3; for the purposes of this paper, all electronic products noted above are referred to as ENDS. In addition, youth were asked about their use of bidis and kreteks but these data were not included in the analyses due to small sample sizes.

The PATH Study questionnaire describes hookah as a type of waterpipe that is often used to smoke tobacco in groups at cafés or hookah bars. Generic pictures of hookah were displayed on the screen for respondents prior to questioning. Respondents were asked if they had ever heard of hookah; if they had, questions regarding ever use and frequency of use were asked. Ever, P12M, and P30D tobacco use were assessed at W1, W2, and W3 among youth, young adults, and adults 25+ for hookah and other tobacco products.

Outcome measures

Cross-sectional definitions of use included ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D use. Longitudinal outcomes included P12M persistent hookah use (continued exclusive or hookah polytobacco use at W2 and W3), discontinued hookah use (stopped hookah use at W2 and W3 or just W3), and reuptake of hookah use (hookah use at W1, stopped hookah use at W2, and used hookah again at W3), as well as transitions among exclusive and polytobacco hookah users. The definition of each outcome is included in the footnote of the table/figure in which it is presented.

Analytic Approach

To address Aim 1, weighted cross-sectional prevalence of hookah use was estimated for ever, P12M, P30D, daily P30D use at each wave stratified by age. For Aim 2, longitudinal W1-W2-W3 transitions in any P12M hookah use were summarized to represent pathways of persistent any P12M hookah use, discontinued any P12M hookah use, and reuptake of any P12M hookah use at W3. Finally, for Aim 3, longitudinal W1-W2-W3 hookah use pathways that flow through seven mutually exclusive and exhaustive transition categories were examined for W1 P12M exclusive hookah users, W1 P12M hookah polytobacco use with cigarettes (w/CIGS), and W1 P12M hookah polytobacco use without cigarettes (w/o CIGS) (see Supplemental Figure 3). For each aim, weighted t-tests were conducted on differences in proportions to assess statistical significance. To correct for multiple comparisons, Bonferroni post-hoc tests were conducted. Given that combustible cigarettes are the most commonly used tobacco product with the most robust evidence base of harmful health consequences,29 polytobacco use groups were examined separately to compare longitudinal transitions among polytobacco users who use and do not use combustible cigarettes. These pathways represent building blocks that can be aggregated to reflect higher-level behavioral transitions. Hookah use is episodic and does not typically occur as frequently as use of other tobacco products; hence, we have used P12M use as the definition of use to examine transitions across three waves.

Cross-sectional estimates (Aim 1) were calculated using the PATH Study cross-sectional weights for W1 and single-wave (pseudo-cross-sectional) weights for W2 and W3. The weighting procedures adjusted for complex study design characteristics and nonresponse. Combined with the use of a probability sample, the weighted data allow these estimates to be representative of the noninstitutionalized, civilian, resident U.S. population aged 12 or older at the time of each wave. Longitudinal estimates (Aims 2 and 3) were calculated using the PATH Study W3 all-waves weights. These weighted estimates are representative of the resident U.S. population aged 12 and older at the time of W3 (other than those who were incarcerated) who were in the civilian, noninstitutionalized population at Wave 1.

All analyses were conducted using SAS Survey Procedures, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Variances were estimated using the balanced repeated replication method30 with Fay’s adjustment set to 0.3 to increase estimate stability.31 Analyses were run on the W1-W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8). Estimates with low precision (fewer than 50 observations in the denominator or with a relative standard error greater than 0.30) were flagged and are not discussed in the Results. Respondents missing a response to a composite variable (e.g., ever, P12M) were treated as missing; missing data were handled with listwise deletion.

RESULTS

Cross-Sectional Weighted Prevalence

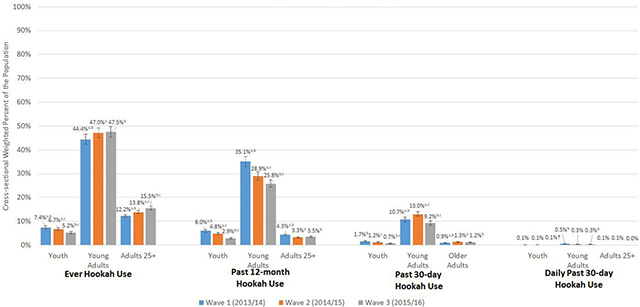

As shown in Figure 1, young adults had the highest prevalence of ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D hookah use, compared to youth and adults 25+. Among young adults, P12M hookah use decreased from 35.1% (95% CI: 33.0–37.1) at W1 to 25.8% (95% CI: 24.2–27.3) at W3. P12M hookah use also decreased among youth from 6.0% (95% CI: 5.4–6.7) at W1 to 2.9% (95% CI: 2.6%−3.3%) at W3. Among young adults, P30D hookah use decreased from 13.0% (95% CI: 12.1–14.0) at W2 to 9.2% (95% CI: 8.3–10.2) at W3. Prevalence of P30D use was less than 2% among youth and adults 25+. Less than 1% of youth, young adults, and adults 25+ used hookah daily.

Figure 1:

Cross-sectional weighted percent of ever, P12M, P30D and daily P30D hookah use among youth, young adults and adults 25+ in W1, W2 and W3 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Abbreviations: P12M = past 12-month; P30D = past 30-day; W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3 W1/W2/W3 ever hookah use unweighted Ns: youth (ages 12–17) = 1,005/799/597; young adults (ages 18–24) = 5,061/4,370/4,144; adults 25+ (ages 25 and older) = 5,561/5,430/5,776W1/W2/W3 P12M hookah use unweighted Ns: youth = 815/584/344; young adults = 3,665/2,726/2,357; adults 25+ = 1,899/1,341/1,427W1/W2/W3 P30D hookah use unweighted Ns: youth = 226/153/72; young adults = 1,261/1,244/867; adults 25+ = 459/530/473W1/W2/W3 Daily P30D hookah use unweighted Ns: youth = 14/15/7; young adults = 61/37/28; adults 25+ = 29/27/16 X-axis shows four categories of hookah use (ever, P12M, P30D, and daily P30D). Y-axis shows weighted percentages of W1, W2, and W3 users. Sample analyzed includes all W1, W2, and W3 respondents at each wave. All respondents with data at one wave are included in the sample for that wave’s estimate and do not need to have complete data at all three waves. The PATH Study cross-sectional (W1) or single-wave weights (W2 and W3) were used to calculate estimates at each wave. Ever hookah use is defined as having ever used a Hookah, even once or twice in lifetime. P12M hookah use is defined as any hookah use within the past 12 months. P30D hookah use is defined as any hookah use within the past 30 days. Daily P30D hookah use is defined as use of hookah on all 30 of the past 30 days. All use definitions refer to any use that includes exclusive or polytobacco use of hookah. a denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 and W2 b denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 and W3 c denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W2 and W3 The logit-transformation method was used to calculate the 95% confidence intervals. † Estimate should be interpreted with caution because it has low statistical precision. It is based on a denominator sample size of less than 50, or the coefficient of variation of the estimate or its complement is larger than 30%. Analyses were run on the W1, W2, and W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8).

Longitudinal Weighted W1-W2-W3 Pathways

Among P12M hookah users at W1

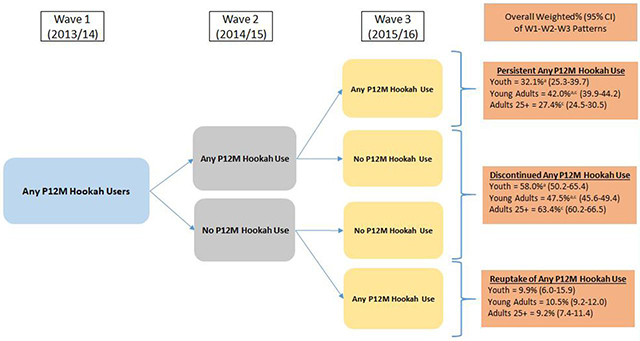

Drawing from the weighted longitudinal sample with data at all three waves, 5.9% (95% CI: 5.3–6.5) of youth, 35.2% (95% CI: 33.0–37.5) of young adults, and 4.2% (95% CI: 3.9–4.5) of adults 25+ were P12M hookah users at W1. Figure 2 presents three-wave any P12M use and non-use pathways. Among W1 P12M hookah users, persistent P12M hookah use was highest among young adults (42.0% [95% CI: 39.9–44.2]) compared to youth (32.1% [95% CI: 25.3–39.7]) and adults 25+ (27.4% [95% CI: 24.5–30.5]). Similarly, discontinued hookah use was higher among adults 25+ (63.4% [95% CI: 60.2– 66.5]) and youth (58.0% [95% CI: 50.2– 65.4]) compared to young adults (47.5% [95% CI: 45.6–49.4]). Overall, the most common pathway among W1 hookah P12M users was discontinued use by W3 across all three age groups (Three-wave any P30D pathways are presented in Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Patterns of W1-W2-W3 persistent any P12M hookah use, discontinued any P12M hookah use and reuptake of any P12M hookah use among W1 any P12M hookah users. Abbreviations: W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3; P12M = past 12-month; CI = confidence interval Wave 1 any P12M hookah use weighted percentages (95% CI) out of total U.S. population: youth (ages 12–17) = 5.9% (5.3–6.5); young adults (ages 18–24) = 35.2% (33.0–37.5); adults 25+ (ages 25 and older) = 4.2% (3.9–4.5) Analysis included W1 youth, young adults, and adults 25+ P12M Hookah users with data at all three waves. Respondent age was calculated based on age at W1. W3 longitudinal (all-waves) weights were used to calculate estimates. These rates vary slightly from those reported in Figure 1 or Supplemental Table 1 because this analytic sample in Figure 2 includes only those with data at each of the three waves to examine weighted longitudinal use and non-use pathways. Any P12M hookah use was defined as any hookah use within the past 12 months. Respondent could be missing data on other P12M tobacco product use and still be categorized into the following three groups:1) Persistent any P12M hookah use: Defined as exclusive or hookah polytobacco use at W2 and W3.2) Discontinued any P12M hookah use: Defined as any non-hookah use or no tobacco use at either W2 and W3 or just W3.3) Reuptake of any P12M hookah use: Defined as discontinued hookah use at W2 and any hookah use at W3. a denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between youth and young adults b denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between youth and adults 25+ c denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between young adults and adults 25+ The logit-transformation method was used to calculate the 95% CIs. Analyses were run on the W1, W2, and W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8).

Among P12M exclusive hookah users, P12M hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS, and P12M hookah polytobacco users w/o CIGS at W1

Among W1 P12M hookah users, most were hookah users who also used another tobacco product (youth: 73.9% [95% CI: 69.8–77.6], young adults: 80.5% [95% CI: 78.6–82.2], adults 25+: 83.2% [95% CI: 80.6–85.6]). Among W1 P12M hookah smokers, 49.4% (95% CI: 44.9–53.9) of youth, 59.4% (95% CI: 57.0–61.8) of young adults, and 63.2% (95% CI: 59.7–66.5) of adults 25+ were hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS, and 24.5% (95% CI: 21.3–28.0) of youth, 21.0% (95% CI: 19.2–22.9) of young adults, and 20.0% (95% CI: 17.4–23.0) of adults 25+ were hookah polytobacco users w/o CIGS. In comparison, 26.1% (95% CI: 22.4–30.2) of youth, 19.6% (95% CI: 18.0–21.4) of young adults, and 16.8% (95% CI: 14.5–19.4) of adults 25+ were exclusive P12M hookah users (Supplemental Figure 3 footnote). Aim 3 of this study examined 49 possible W1-W2-W3 pathways across seven mutually exclusive categories (see conceptual map in Supplemental Figure 3) among the three W1 categories: 1) P12M exclusive hookah users, 2) P12M hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS, and 3) P12M hookah polytobacco users w/o CIGS. Described below are aggregated pathways from Table 1 (based on Supplemental Tables 2a, 2b, and 2c) that estimate broad behavioral transitions such as persistent use, tobacco cessation and relapse among youth, young adults and adults 25+.

Table 1:

Transitions in P12M Product Use at W2 and W3 Among W1 P12M Hookah Users.

| Youth | Young Adults | Adults 25+ | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 Exclusive Hookah Use | W1 Hookah PTU w/CIGS | W1 Hookah PTU w/o CIGS | W1 Exclusive Hookah Use | W1 Hookah PTU w/CIGS | W1 Hookah PTU w/o CIGS | W1 Exclusive Hookah Use | W1 Hookah PTU w/CIGS | W1 Hookah PTU w/o CIGS | ||||||||||

| Mutually Exclusive Pathways | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI |

|

Persistent hookah use type at all

waves Continuing the same W1 use type (exclusive, PTU w/CIGS, or PTU w/o CIGS) at each wave |

6.7†a | (3.6-12.1) | 42.2a,c | (35.7-48.9) | 12.4c | (7.7-19.4) | 7.8a,b | (5.5-10.9) | 35.0a,c | (32.0-38.2) | 14.8b,c | (11.6-18.9) | 7.2a | (4.3-11.9) | 25.2a,c | (21.6-29.3) | 12.3c | (8.3-17.7) |

|

Hookah use type

reuptake The same broad use type (exclusive or PTU) at W1 and W3 (but a different tobacco use at W2) |

1.1†a,b | (0.3-4.5) | 17.2a,c | (13.2-22.1) | 36.1b,c | (28.3-44.6) | 4.7a,b | (2.8-7.8) | 17.3a,c | (15.4-19.5) | 26.0b,c | (22.1-30.3) | 1.8†a,b | (0.7-4.4) | 11.9a | (9.9-14.4) | 12.2b | (8.9-16.5) |

|

Hookah use type

transition Transition from W1 exclusive use to PTU by W3, or transition from W1 PTU to exclusive use by W3 (without discontinuing all tobacco use at W2) |

41.7a,b | (34.9-48.9) | 2.3†a | (1.0-5.4) | 1.5†b | (0.3-6.4) | 28.3a,b | (23.5-33.7) | 1.9a,c | (1.2-3.0) | 5.8b,c | (4.1-8.2) | 16.2a,b | (11.2-22.9) | 1.9†a,c | (0.9-3.8) | 5.4b,c | (3.3-8.8) |

|

Switch or discontinue hookah use, but

continue other tobacco use W1 exclusive user who switches to another tobacco product by W3 or W1 polytobacco user that discontinues hookah use by W3 but uses another tobacco product (without discontinuing all tobacco use at W2) |

11.7a,b | (7.3-18.3) | 28.5a | (23.3-34.4) | 22.7b | (16.4-30.7) | 11.1a,b | (8.6-14.2) | 37.7a,c | (34.5-41.0) | 24.6b,c | (20.6-29.0) | 5.3a,b | (3.0-9.4) | 53.2a,c | (49.1-57.2) | 36.5b,c | (29.5-44.1) |

|

Tobacco use reuptake W1 users who discontinue all tobacco use at W2 and use again at W3 |

8.3 | (4.7-14.2) | 2.4†c | (1.0-5.8) | 9.4c | (5.6-15.3) | 9.6a | (6.9-13.1) | 1.9a,c | (1.2-2.9) | 5.6c | (4.0-7.9) | 11.9a | (7.5-18.3) | 1.1†a | (0.5-2.2) | 4.6† | (2.5-8.3) |

|

Discontinue all tobacco

use W1 users who discontinue all tobacco use at either W2 and W3 or just W3 |

30.5a,b | (23.8-38.1) | 7.4a,c | (4.9-10.9) | 17.9b,c | (12.2-25.4) | 38.5a,b | (33.3-44.0) | 6.2a,c | (5.0-7.6) | 23.1b,c | (19.1-27.7) | 57.6a,b | (49.1-65.6) | 6.7a,c | (4.9-9.1) | 29.0b,c | (21.9-37.2) |

Notes:

Abbreviations: P12M = past 12-month; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3; W1 = Wave 1; polytobacco use = PTU; w/ = with; CIGS = cigarettes; w/o = without; CI = confidence interval

Analysis included youth (ages 12–17), young adult (ages 18–24), and adult 25+ (ages 25 and older) W1 P12M hookah users with data at all three waves. Respondent age was calculated based on age at W1. W3 longitudinal (all-waves) weights were used to calculate estimates. All tobacco use is defined as P12M use. Use type refers to exclusive use, PTU w/CIGS, or PTU w/o CIGS.

denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 Exclusive Hookah Use and W1 Hookah PTU w/CIGS

denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 Exclusive Hookah Use and W1 Hookah PTU w/o CIGS

denotes significant difference at p<0.0167 (Bonferroni corrected for three comparisons) between W1 Hookah PTU w/CIGS and W1 Hookah PTU w/o CIGS

The logit-transformation method was used to calculate the 95% CIs.

Estimate should be interpreted with caution because it has low statistical precision. It is based on a denominator sample size of less than 50, or the coefficient of variation of the estimate or its complement is larger than 30%.

Analyses were run on the W1, W2, and W3 Public Use Files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v8).

Among Youth

As shown in Table 1, persistent use was higher among W1 P12M hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS (42.2% [95% CI: 35.7–48.9]) compared to hookah polytobacco users w/o CIGS (12.4% [95% CI: 7.7–19.4]). Reuptake of hookah use was higher among W1 P12M hookah polytobacco users w/o CIGS (36.1% [95% CI: 28.3–44.6]) compared to hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS (17.2% [95% CI: 13.2–22.1]). Discontinued all tobacco use was the highest among W1 exclusive P12M users (30.5% [95% CI: 23.8– 38.1]) compared to W1 P12M hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS (7.4% [95% CI: 4.9– 10.9]) and P12M hookah polytobacco users w/o CIGS (17.9% [95% CI: 12.2– 25.4]).

Among Young Adults

As shown in Table 1, persistent use was higher among W1 P12M hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS (35.0% [95% CI: 32.0–38.2]) than exclusive hookah users (7.8% [95% CI: 5.5–10.9]) and hookah polytobacco users w/o CIGS (14.8% [95% CI: 11.6– 18.9]). Discontinued all tobacco use was the highest among W1 exclusive P12M hookah users (38.5% [95% CI: 33.3– 44.0]) compared to W1 P12M hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS (6.2% [95% CI: 5.0– 7.6]) and w/o CIGS (23.1% [95% CI: 19.1– 27.7]). Transition to hookah polytobacco among W1 exclusive P12M hookah users was higher (28.3% [95% CI: 23.5–33.7]) than transition to exclusive hookah use among W1 P12M hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS (1.9% [95% CI: 1.2– 3.0]) and w/o CIGS (5.8% [95% CI: 4.1– 8.2]). One notable pattern regarding W1 P12M hookah polytobacco use w/CIGS involved those who discontinued hookah but continued other products. For example, Supplemental Table 1b, row 27, shows that 11.7% (95% CI: 9.8–13.9) of W1 P12M young adult hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS continued smoking cigarettes at W3 after stopping hookah use.

Among Adults 25+

As shown in Table 1, persistent use was higher among W1 P12M hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS (25.2% [95% CI: 21.6–29.3]) than exclusive hookah users (7.2% [95% CI: 4.3–11.9]) and hookah polytobacco users w/o CIGS (12.3% [95% CI: 8.3– 17.7]). Discontinued all tobacco use was the highest among W1 exclusive P12M hookah users (57.6% [95% CI: 49.1– 65.6]) compared to W1 P12M hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS (6.7% [95% CI: 4.9– 9.1]) and w/o CIGS (29.0% [95% CI: 21.9– 37.2]). Discontinuing hookah use and continuing other tobacco products was higher among W1 P12M hookah polytobacco users w/CIGS (53.2% [95% CI: 49.1– 57.2]) than polytobacco users w/o CIGS (36.5% [95% CI: 29.5–44.1]).

DISCUSSION

Overall, weighted cross-sectional analyses found that young adults had higher rates of hookah use at each of three time points from 2013–2016 compared to youth and adults 25+, though prevalence of P30D hookah use in young adults decreased from W1-W3. This study also found that most W1 P12M hookah users across all age groups used at least one other tobacco product, and adults 25+ had higher rates of hookah polytobacco use w/CIGS compared to youth and young adults. This finding replicates other reports that found higher rates of polytobacco use among hookah smokers.12,15,32,33

Longitudinal patterns of P12M use across three waves showed that the most common pathway of hookah use across the three age groups was discontinuation (i.e., P12M use at W1 and no P12M use at W2 or W3). The literature is robust with cross-sectional studies that report hookah is used infrequently.11,15,34 Therefore, it is unclear if non-P12M use can be regarded as having quit the product because respondents may not have used hookah within the past year of the interview but may still be using hookah intermittently with no intention to quit using it given the infrequent social smoking aspect of it. This study also found that less than 27.4– 42% of hookah users in each age group were P12M users of hookah at all three waves.

In terms of longitudinal transitions among exclusive and polytobacco hookah users, distinct patterns of hookah use and non-use across three waves were observed, as shown in Table 1. Discontinued hookah was the most common pathway among W1 exclusive hookah users across all age groups. Longitudinal pathways of P12M exclusive or hookah polytobacco use showed that W1 P12M exclusive hookah users discontinued all tobacco at much higher rates than hookah polytobacco users, especially among adults 25+. These findings suggest that hookah polytobacco users are more likely to persist using tobacco products other than hookah. This may be because polytobacco users have more difficulty quitting tobacco compared to exclusive users due to higher nicotine dependence among polytobacco users.35 Furthermore, our results also showed that those who used hookah and cigarettes had lower rates of discontinuing all tobacco, compared to hookah polytobacco users who did not use cigarettes and were more likely to discontinue using hookah but continue to use other tobacco products. Among W1 young adults who used hookah and cigarettes and who later discontinued hookah but continued other tobacco product use, almost 12% continued smoking cigarettes at W3 (Supplemental Table 1b). This may be because hookah use is a transitional phase among cigarette smokers where cigarette smokers infrequently experiment with hookah use but do not continue to use it on a regular basis.36

Overall, longitudinal patterns of hookah use appear to be similar to those of some products such as ENDS but different from cigarettes and smokeless tobacco. For example, high rates of discontinuing product use were common for hookah, ENDS, and cigars as reported by Stanton et al.37 and Edwards et al.37,38 Use of tobacco products such as hookah and ENDS is more common among young adults, who experiment with tobacco products and use them infrequently.39–41 These products may be driven by similar motivational factors like socializing in hookah bars and vape shops, availability of appealing flavors, beliefs that these products could be less harmful than cigarette smoking and by pervasive misconceptions that products like hookah have low probability of addiction and quitting is not as difficult.1,36 In contrast, among cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, patterns of persistent use are more common.42,43 Health prevention interventions designed to increase awareness about harms of hookah smoking may be valuable in reducing initiation and limiting widespread use of hookah especially among youth and young adults.

Limitations

This study provides a unique perspective on hookah use based on a large, nationally representative design and describes cross-sectional and longitudinal transition patterns among hookah users across three age groups in the U.S. population. Limitations include use of self-reported data, which are subject to recall bias. Small sample sizes in some groups, especially among hookah users who do not use cigarettes, limited meaningful interpretations of those pathways. In addition, this study defined discontinued hookah use as no P12M use, without any consideration of intent to quit. Discontinuance based on P12M use may not be the best measure to assess cessation, considering infrequent use patterns among many hookah users. Future research can explore pathways of cessation using different definitions of non-use and incorporating frequency and intensity of use. Future studies can also examine correlates that predict these unique patterns among exclusive and non-exclusive hookah users. Kasza et al.44,45 and Edwards et al.46 examine demographic correlates of initiation, cessation, and relapse of hookah use to further explore predictors of these outcomes.

Summary and Implications

This study of hookah use suggests distinct longitudinal patterns among exclusive hookah users and polytobacco users who use hookah with and without cigarettes. Findings show that discontinuation of all tobacco is the most common pathway among hookah users who do not concurrently smoke cigarettes; however, hookah users who use hookah but also use cigarettes continue smoking cigarettes. The use of cigarettes along with hookah appears to be a noteworthy factor in continued tobacco use. Given the popularity of hookah among young adults, future work can help better understand why some hookah users cease using the product while others persist in using it. Results of this study are intended to offer detailed transitional patterns to serve as building blocks that researchers can aggregate to clearly understand hookah use in the population. The FDA finalized a rule extending its regulatory authority to cover all tobacco products, including hookah tobacco, components, and parts.17 These findings could be useful in determining the most appropriate regulatory approaches for hookahs.

Supplementary Material

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

Very little is known about longitudinal patterns of hookah use in the U.S. population, especially among exclusive and hookah polytobacco users.

Longitudinal pathways of P12M hookah polytobacco users showed higher rates of discontinuation of all tobacco use among hookah users who did not smoke cigarettes compared to those who used both hookah and cigarettes.

Most W1 P12M hookah users across all age groups used at least one other tobacco product, and adults 25+ had higher rates of hookah polytobacco use with cigarettes compared to youth and young adults.

Understanding patterns of hookah use could help inform hookah-related regulations.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This manuscript is supported with Federal funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, and the Center for Tobacco Products, Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, under a contract to Westat (Contract No. HHSN271201100027C).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies.

Financial disclosure: Wilson Compton reports long-term stock holdings in General Electric Company, 3M Company, and Pfizer Incorporated, unrelated to this manuscript. No financial disclosures were reported by the other authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Bhatnagar A, Maziak W, Eissenberg T, et al. Water pipe (hookah) smoking and cardiovascular disease risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(19):e917–e936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasza KA, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Tobacco-Product Use by Adults and Youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salloum RG, Thrasher JF, Kates FR, Maziak W. Water pipe tobacco smoking in the United States: findings from the National Adult Tobacco Survey. Preventive medicine. 2015;71:88–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Primack BA, Carroll MV, Weiss PM, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of inhaled toxicants from waterpipe and cigarette smoking. Public Health Reports. 2016;131(1):76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S, Saini A, Mittal V, Singh U, Singh V. Breath carbon monoxide levels in different forms of smoking. Indian Journal of Chest Diseases and Allied Sciences. 2011;53(1):25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students-United States, 2011–2014. MMWRMorb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(14):381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gentzke AS, Creamer M, Cullen KA, et al. Vital Signs: Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu S, Neff L, Agaku I, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults-United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(27):685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agaku IT, King BA, Husten CG, et al. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2012–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(25):542–547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnett TE, Smith T, He Y, et al. Evidence of emerging hookah use among university students: a cross-sectional comparison between hookah and cigarette use. BMC public health. 2013;13(1):302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fielder RL, Carey KB, Carey MP. Prevalence, frequency, and initiation of hookah tobacco smoking among first-year female college students: a one-year longitudinal study. Addictive behaviors. 2012;37(2):221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarrett T, Blosnich J, Tworek C, Horn K. Hookah use among US college students: results from the National College Health Assessment II. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14(10):1145–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majeed BA, Sterling KL, Weaver SR, Pechacek TF, Eriksen MP. Prevalence and harm perceptions of hookah smoking among US adults, 2014–2015. Addictive behaviors. 2017;69:78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasza KA, Borek N, Conway KP, et al. Transitions in Tobacco Product Use by U.S. Adults between 2013(−)2014 and 2014(−)2015: Findings from the PATH Study Wave 1 and Wave 2. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Primack BA, Shensa A, Kim KH, et al. Waterpipe smoking among US university students. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;15(1):29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palamar JJ, Zhou S, Sherman S, Weitzman M. Hookah use among US high school seniors. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):227–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Food and Drug Administration (HHS). Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; restrictions on the sale and distribution of tobacco products and required warning statements for tobacco products. Final rule. Federal Register. 2016;81(90):28973–29106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khabour OF, Alzoubi KH, Bani-Ahmad M, Dodin A, Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Acute exposure to waterpipe tobacco smoke induces changes in the oxidative and inflammatory markers in mouse lung. Inhalation toxicology. 2012;24(10):667–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koul PA, Hajni MR, Sheikh MA, et al. Hookah smoking and lung cancer in the Kashmir valley of the Indian subcontinent. Asian Pac JCancer Prev. 2011;12(2):519–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montazeri Z, Nyiraneza C, El-Katerji H, Little J. Waterpipe smoking and cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Tobacco control. 2017;26(1):92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rammah M, Dandachi F, Salman R, Shihadeh A, El-Sabban M. In vitro effects of waterpipe smoke condensate on endothelial cell function: a potential risk factor for vascular disease. Toxicology letters. 2013;219(2):133–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waziry R, Jawad M, Ballout RA, Al Akel M, Akl EA. The effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking on health outcomes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2016;46(1):32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Retzky SS. Carbon monoxide poisoning from hookah smoking: an emerging public health problem. Journal of medical toxicology. 2017;13(2):193–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnett TE, Lorenzo FE, Soule EK. Hookah smoking outcome expectations among young adults. Substance use & misuse. 2017;52(1):63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hair E, Rath JM, Pitzer L, et al. Trajectories of Hookah Use: Harm Perceptions from Youth to Young Adulthood. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2017;41(3):240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wackowski OA, Delnevo CD. Young adults’ risk perceptions of various tobacco products relative to cigarettes: results from the National Young Adult Health Survey. Health Education & Behavior. 2016;43(3):328–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Tobacco control. 2016:tobaccocontrol-2016–052934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tourangeau R, Yan T, Sun H, Hyland A, Stanton CA. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) reliability and validity study: selected reliability and validity estimates. Tobacco control. 2018:tobaccocontrol-2018–054561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014:943. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCarthy PJ. Pseudoreplication: further evaluation and applications of the balanced half-sample technique. 1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Judkins DR. Fay’s method for variance estimation. Journal of Official Statistics. 1990;6(3):223. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, Kim AE. Multiple tobacco product use among adults in the United States: cigarettes, cigars, electronic cigarettes, hookah, smokeless tobacco, and snus. Prev Med. 2014;62:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMillen R, Maduka J, Winickoff J. Use of emerging tobacco products in the United States. Journal of environmental and public health. 2012;2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heinz AJ, Giedgowd GE, Crane NA, et al. A comprehensive examination of hookah smoking in college students: use patterns and contexts, social norms and attitudes, harm perception, psychological correlates and co-occurring substance use. Addictive behaviors. 2013;38(11):2751–2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sung H-Y, Wang Y, Yao T, Lightwood J, Max W. Polytobacco use and nicotine dependence symptoms among US adults, 2012–2014. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2018;20(suppl_1):S88–S98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper M, Pacek LR, Guy MC, et al. Hookah Use among US Youth: A Systematic Review of the Literature from 2009–2017. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanton CA, Sharma E, Edwards KC, et al. Longitudinal transitions of exclusive and polytobacco electronic nicotine delivery systems (ends) use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s147–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards KC, Sharma E, Halenar MJ, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco cigar use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s163–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang TW, Gentzke A, Sharapova S, Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Jamal A. Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Villanti AC, Pearson JL, Glasser AM, et al. Frequency of Youth E-Cigarette and Tobacco Use Patterns in the United States: Measurement Precision Is Critical to Inform Public Health. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2016;19(11):1345–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agaku I, Odani S, Armour B, Glover-Kudon R. Social Aspects of Hookah Smoking Among US Youth. Pediatrics. 2018:e20180341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma E, Edwards KC, Halenar MJ, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco smokeless use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s170–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor KA, Sharma E, Edwards KC, et al. Longitudinal pathways of exclusive and polytobacco cigarette use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s139–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kasza K, Edwards KC, Tang Z, et al. Correlates of tobacco product initiation among youth and adults in the United States: findings from the path study waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kasza K, Edwards KC, Tang Z, et al. Correlates of tobacco product cessation among youth and adults in the United States: findings from the path study waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s203–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edwards KC, Kasza K, Tang Z, et al. Correlates of tobacco product relapse among youth and adults in the United States: findings from the path study waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control 2020;29:s216–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.