Abstract

Objectives

Conduct a head-to-head experimental test of responses to alcohol harm reduction advertisements developed by alcohol industry Social Aspects/Public Relations Organisations (SAPROs) versus those developed by public health (PH) agencies. We hypothesised that, on average, SAPRO advertisements would be less effective at generating motivation (H1) and intentions to reduce alcohol consumption (H2) but more effective at generating positive perceptions of people who drink (H3).

Design

Online experiment with random assignment to condition.

Participants

2923 Australian adult weekly drinkers (49% high-risk drinkers) recruited from an opt-in online panel.

Interventions

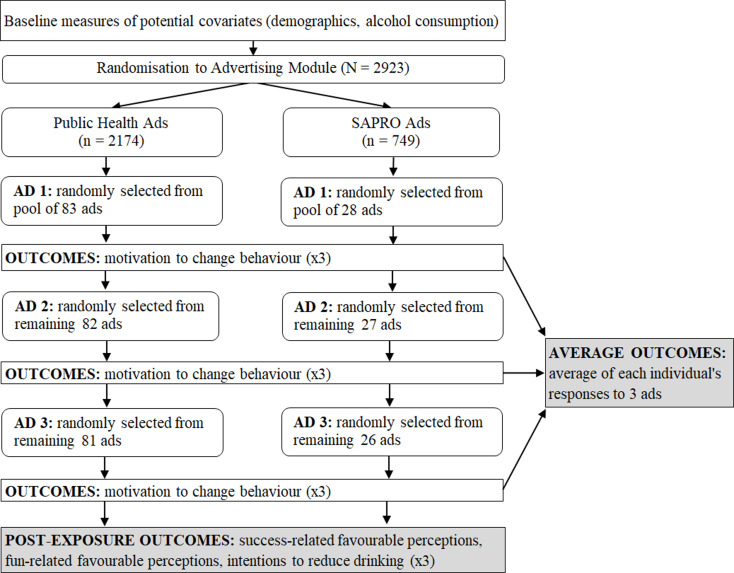

Participants viewed 3 of 83 advertisements developed by PH agencies (n=2174) or 3 of 28 advertisements developed by SAPROs (n=749).

Primary outcome measures

Participants reported their motivation to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed; behave responsibly and/or not get drunk; and limit their drinking around/never supply to minors, as well as intentions to avoid drinking alcohol completely; reduce the number of drinking occasions; and reduce the amount of alcohol consumed per occasion. Participants also reported their perceptions of people who drink alcohol on six success-related items and four fun-related items.

Results

Compared with drinkers exposed to PH advertisements, those exposed to SAPRO advertisements reported lower motivation to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed (β=−0.091, 95% CI −0.171 to −0.010), and lower odds of intending to avoid alcohol completely (OR=0.77, 0.63 to 0.94) and to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed per occasion (OR=0.82, 0.69 to 0.97). SAPRO advertisements generated more favourable fun-related perceptions of drinkers (β=0.095, 0.013 to 0.177).

Conclusions

The alcohol harm reduction advertisements produced by alcohol industry SAPROs that were tested in this study were not as effective at generating motivation and intentions to reduce alcohol consumption as those developed by PH organisations. These findings raise questions as to whether SAPROs should play a role in alcohol harm reduction efforts.

Keywords: public health, preventive medicine, education & training (see medical education & training)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Responses to alcohol harm reduction advertisements were provided by a large sample of adult weekly drinkers randomly assigned to watch advertisements produced by either public health agencies or alcohol industry Social Aspects/Public Relations Organisations (SAPROs).

All advertisements were presented in a standard way with consistent exposure, although such exposure may not reflect conditions of usual advertisement exposure.

Although small effect sizes were observed, these signal the possibility of large and meaningful differences in effectiveness at the population level when advertisements are broadcast in mass-reach multimedia campaigns.

The absence of a control condition means we cannot claim that advertisements produced by SAPROs were ineffective, or conversely that advertisements produced by public health agencies were effective.

Background

Alcohol is one of the top five global causes of preventable death, disease and injury,1 with over three million deaths annually and 5.1% of disability-adjusted life years lost attributable to alcohol consumption.2 In direct conflict with its substantial investment in marketing and promoting alcohol consumption,3 4 the alcohol industry has become increasingly involved in the development and delivery of mass media campaigns purportedly aimed at reducing the harmful use of alcohol.5 Extant research on industry-sponsored tobacco harm reduction messages has shown that these are less effective or even counterproductive relative to advertisements developed by public health (PH) agencies,6–8 but less research has examined the impact of industry-sponsored alcohol harm reduction advertising. This study aimed to address this gap by conducting the first head-to-head experimental test of alcohol harm reduction advertisements produced by the alcohol industry compared with those produced by PH agencies. Should advertisements funded by the alcohol industry prove to be less effective than PH advertisements—overall or among key demographic subgroups—then their potential utility in helping to reduce harmful alcohol use would be called into question. Such evidence may help to inform deliberations regarding the industry’s role in the development and delivery of alcohol harm reduction interventions.

Many of the supposed alcohol harm reduction campaigns recently funded by the alcohol industry have been developed by their Social Aspects/Public Relations Organisations (SAPROs). SAPROs are organisations that combine the resources of multiple alcohol companies to promote policies most favourable to industry while also presenting an outward image of being socially responsible.9 10 SAPROs often implement alcohol harm reduction campaigns as part of their efforts to present the industry as a credible and responsible corporate citizen and to deflect government scrutiny, criticism and regulation.11–13

If SAPRO-produced alcohol harm reduction campaigns were to achieve their stated objectives, then the ultimate impact would be to reduce alcohol consumption, and hence, industry profits. On the basis of this inherent conflict of interest, PH experts have recommended the alcohol industry should not be involved in the delivery of alcohol-related information and education. They are concerned that industry-funded campaigns and other communication activities may ultimately serve to benefit the industry more than PH.14–17 For example, recent analyses of the content of SAPRO websites have identified several ways in which these sites misrepresent the evidence about the link between alcohol and cancer18 and about the effects of alcohol consumption during pregnancy.19 Furthermore, a recent review of corporate social responsibility activities implemented by the alcohol industry (including harm reduction campaigns) found no robust evidence that these activities have reduced harmful drinking; rather, several studies provided evidence of effects favourable to the industry.20

Industry-funded alcohol harm reduction campaigns may undermine PH goals by delaying, displacing or even reducing the effectiveness of campaigns from more conventional health promotion sources.16 17 There is also evidence that these campaigns sometimes employ message strategies that, either implicitly or explicitly, may have the effect of encouraging rather than discouraging alcohol consumption.21–23 In 1992, DeJong and colleagues found that responsible drinking advertisements sponsored by beer companies contained prominent images of alcoholic beverages, and depicted scenes (eg, bar scenes, party scenes) and themes (eg, relaxation, celebration, romantic and sexual conquests) commonly used in alcohol advertisements. In fact, sometimes the visuals employed in the responsible drinking advertisements were lifted directly from concurrently aired product advertisements. DeJong et al argued that these industry-funded advertisements ensured that any pro-health message ostensibly conveyed by the advertisement was undermined by both subtle and overt messages about the potential benefits of drinking alcohol.21

In a more recent study assessing responses to the ‘How To Drink Properly’ campaign, produced by the SAPRO DrinkWise Australia in 2014, Pettigrew and colleagues found that the repetitive images of alcohol consumption, and the use of an attractive and charismatic James Bond-like spokesperson, led many young adults to interpret the advertisement as encouraging drinking and reinforcing the role of alcohol in young people’s lives.23 This campaign has been criticised for glamorising drinking through associating the behaviour with images of style and sophistication, and for promoting the concept of a ‘realm of drinking excellence’.13 Industry-funded campaigns that appear to discourage underage drinking may also have the opposite effect of encouraging consumption if they emphasise that drinking is an adult behaviour; when such a strategy was used in Philip Morris’ youth smoking prevention campaign in the USA, it was found to increase rather than decrease youth interest in smoking.7

DeJong and colleagues also noted that the vague slogans used in industry-sponsored responsible drinking campaigns typically presumed drinking (eg, ‘Drink Responsibly’) and disregarded the cognitive impairment that occurs when drinking (eg, ‘Think When You Drink’).21 More than 20 years later, DrinkWise’s ‘How To Drink Properly’ campaign employed similar strategies, and young adults noted that the advertisement failed to provide a tangible definition of responsible drinking.23 Industry-funded campaigns have also been characterised as being strategically ambiguous,24–26 such that different people reach different interpretations of the same message.27 For instance, in a recent study in which participants were asked to interpret the slogans used in industry-funded advertisements, several slogans were perceived to have four or more distinct meanings, including both favourable (‘know your limits’) and unfavourable (‘looking cool when you drink’) interpretations.5

There is an urgent need for additional rigorous empirical work to test the potential positive and negative effects of industry-funded campaigns,20 particularly given the substantial resources available from the industry to disseminate these campaigns. In the current study, adult drinkers watched either PH-produced or SAPRO-produced alcohol harm reduction advertisements in a forced exposure online head-to-head experiment, thereby ensuring that exposure to all advertisements occurred in a consistent way and that the relative impact of the PH and SAPRO advertisements was not influenced by the use of different media placement strategies or the varying capacity of PH agencies and the alcohol industry to achieve high levels of campaign exposure. We first aimed to examine the impact of exposure to advertisements on measures typically used to assess the potential effectiveness of PH advertisements; that is, motivation and intentions to behave in ways that reduce alcohol-related harm. Given the lacklustre performance of industry-funded harm reduction advertisements in previous limited research testing their effectiveness5 21–23 and recent evidence that well-designed PH advertisements can increase motivation and intentions to reduce alcohol consumption,28–32 we hypothesised that compared with PH advertisements, alcohol harm reduction advertisements developed by alcohol industry SAPROs would be less effective at generating motivation to reduce alcohol consumption and to behave responsibly in relation to alcohol (H1) and less effective at producing intentions to reduce alcohol consumption over the next week (H2).

One of the features that may contribute to SAPRO advertisements being less effective on these standard public health outcomes is their use of imagery that depicts drinking and people who drink in a positive light, by promoting drinking as glamorous, cool and fun, and emphasising that it can facilitate social interactions and romantic and sexual conquests.5 21 23 It is possible that such imagery serves to promote the benefits of drinking and to undermine any explicit alcohol harm reduction message that the advertisement otherwise appears to contain. Therefore, we also assessed the extent to which exposure to PH and SAPRO advertisements resulted in favourable perceptions of people who drink alcohol. We hypothesised that compared with PH advertisements, exposure to SAPRO advertisements would be more effective at generating favourable perceptions of people who drink (H3), and we predicted that favourable perceptions of people who drink would be negatively correlated with the motivation and intentions outcomes (H4). We also conducted exploratory analyses to examine whether the relative performance of PH and SAPRO advertisements across all outcomes varied according to sex (RQ1a), age (RQ1b) and whether the audience currently drank at levels that put them at a low-risk or high-risk of alcohol-related harm (RQ1c).

Method

Design, setting and participants

This online study included n=2923 Australian weekly drinkers (consumed alcohol at least 1 to 2 days per week on average over the past 12 months) recruited through an online panel that was accredited under the International Organization for Standardization’s (ISO) standards for Access Panels in Market, Opinion and Social Research (AS ISO 26362). Quotas were applied to achieve approximately even numbers of men and women, and younger (18 to 29 years) and older (30 to 64 years) adults (the legal drinking age in Australia is 18 or older33). Participants were ineligible if they were pregnant or worked in health promotion, market research, advertising or the alcohol industry. Besides their involvement as research participants, members of the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Stimuli

The study assessed responses to a total of 111 English-language alcohol harm reduction advertisements (ads) produced between 2006 and 2014. Of the 111 ads, 83 were produced by PH agencies including government bodies and other not-for-profit organisations (PH ads). These ads were drawn from the sample of advertisements included in a recent content analysis of 110 English-language alcohol harm reduction ads produced from 2006 to 2014, which were identified as part of an exhaustive Internet search of Google, YouTube, Vimeo, relevant government and health agency websites.34 For the purposes of the current study, we only included ads that were between 30 and 60 s long (excluding n=10), that targeted adults (rather than children or adolescents (excluding n=8) or governments (excluding n=3)), and were designed to encourage individual behaviour change rather than advocating for policy reform (excluding n=6).

Twenty-eight ads were produced by SAPROs (SAPRO ads). These ads were identified through a search of the websites of all SAPROs known to us at the time of the study (online supplemental appendix A); this search was conducted between July and September 2015. To be eligible for inclusion, ads had to be in English; produced between 2006 and 2014; between 30 and 60 s long; and available for download from the SAPRO website or YouTube. Details and synopses of all 111 ads are provided in online supplemental appendix B.

bmjopen-2019-035569supp001.pdf (211.4KB, pdf)

Procedure

Fieldwork was undertaken in October to November 2015. Members of the online panel were invited to participate via email, and potential participants completed questions assessing eligibility criteria and quotas. As shown in figure 1, eligible participants were then allocated to either the PH or SAPRO advertising condition. Proportional block randomisation35 was used to assign participants according to a predetermined ratio so that the required (but uneven) number of participants would be assigned to each condition, which was n=1937 (required; n=2174 achieved due to a higher than expected completion rate) for the PH ads condition and n=653 (required; n=749 achieved) for the SAPRO ads condition. These sample sizes were determined by a desire to have each ad viewed by an average of 70 participants.31 Following allocation to their condition, each participant was then assigned to view a random 3 of the 83 PH ads or a random 3 of the 28 SAPRO ads. The focus of the study was on comparing participants’ immediate responses to alcohol harm reduction ads produced by different sources; it was beyond the scope of this study to include a no exposure control condition.

Figure 1.

Study procedure. ads, advertisements; SAPRO, Social Aspects/Public Relations Organisation.

Participants viewed their first ad twice and then completed a series of questions assessing their responses. This process was repeated for the remaining two ads. Additional measures were collected following exposure to all three ads (figure 1). Participants were informed prior to viewing the ads that some ads may be from different countries, and that they should focus on the ad’s main message rather than production quality or cultural differences.

Patient and public involvement

There were no patients involved in this study. Members of the public were recruited to the study as participants, as described above.

Outcome measures

Immediately following exposure to each ad, participants completed five items assessing their motivation to change their behaviour: While watching the ad, I felt motivated to (i) reduce the amount of alcohol that I drink, (ii) behave responsibly when I drink alcohol, (iii) limit my drinking so that I don’t get drunk, (iv) limit my drinking when around children and teenagers and (v) never supply alcohol to teenagers (1 ‘strongly disagree’ – 5 ‘strongly agree’). Items (ii) and (iii) were averaged together (α=0.81) into a measure of motivation to behave responsibly and/or not get drunk, and items (iv) and (v) were averaged together (α=0.82) into a measure of motivation to limit drinking around/never supply to minors. Measures of self-reported motivation to engage in behaviour change are often included in measures of perceived message effectiveness,36 including in a scale that has been validated as a predictor of subsequent intention and behaviour change following exposure to tobacco control ads.37

After viewing all three ads, participants responded to three questions about their intentions to consume alcohol: In the next week, how likely is it that you will (i) avoid drinking completely, (ii) reduce the number of occasions when you drink alcohol and (iii) reduce the amount of alcohol you have on each drinking occasion. Responses were provided on a 4-point scale (1 ‘definitely will not’ – 4 ‘definitely will’), but were combined into two categories for analysis, ‘definitely/probably will not’ or ‘definitely/probably will’. Intentions are a well-established, although imperfect, predictor of subsequent behaviour change.38 39

Finally, participants were asked about their perceptions of people who drink alcohol using 10 semantic differential attitudinal statements scored on 7-point scales (‘In your opinion, people who drink alcohol are…’). A preliminary factor analysis indicated that two sets of perception items could be identified based on the data. A success-related favourable perceptions of drinkers scale was created by combining the items: successful, attractive, intelligent, relaxed, healthy and their own person (α=0.86). A fun-related favourable perceptions of drinkers scale combined the items: fun, popular, exciting and confident (α=0.85).

Potential covariates

Ad exposure characteristics

One variable was created to indicate the number of ads from Australia each participant viewed (0, 1, 2 or 3). After each ad, participants were asked if they had seen the ad before (number of ads seen before; 0, 1, 2+ (2 and 3 combined into a single category due to small numbers)).

Drinking characteristics

Prior to viewing the ads, participants reported their average alcohol consumption based on how often in the past 12 months they had consumed each of the following numbers of standard drinks in a day (in Australia, a standard drink is defined as 10 g of alcohol): 20+, 11–19, 7–10, 5–6, 3–4, 1–2, <1 or no alcohol in a day.40 Using the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2009 guidelines for low-risk drinking,41 participants were classified as being at high risk of short-term harm if they reported having >4 drinks on any occasion at least once a month, and at high risk of long-term harm if they consumed >2 drinks per day on average. Participants were then categorised as ‘low-risk drinkers’ (low-risk of short-term and long-term harm) or ‘high-risk drinkers’ (high-risk of short-term and/or long-term harm).

The number of days on which alcohol was consumed in the past week and the total number of drinks consumed in the past week were measured using the 7-day timeline follow-back method.42 The importance of alcohol to an individual’s self-identity was assessed using two questions: ‘Drinking is part of who I am’ and ‘Drinking is part of my personality’ (1 ‘strongly disagree’ – 5 ‘strongly agree’) (α=0.90).

Demographic characteristics

Participants reported their sex, age, highest level of education completed (tertiary vs not tertiary), if they were a parent or guardian of any children and their postcode. Postcode was used to assign location (metropolitan or regional), and the socioeconomic status of the area in which participants lived.43

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/MP 14.2.44 The ad exposure, drinking and demographic characteristics of participants who viewed PH (n=2174) or SAPRO ads (n=749) were compared using t-tests, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests, or χ2 tests (as appropriate). Variable means and proportions for the drinking characteristics, demographic characteristics and number of ads seen that were Australian were not proven different between the two conditions, and so these variables were not included as covariates. However, prior exposure to the ads was not evenly distributed across the two conditions, as participants in the PH ads condition were more likely not to have seen any of the ads before (86.8% vs 82.8%), and conversely, participants in the SAPRO ads condition were more likely to have seen one of the three ads before (13.6% vs 8.8%). Therefore, all models adjusted for the ad familiarity variable (results from unadjusted models are presented in the online supplemental appendix C). Preliminary model checks of linear regression models showed no indications of non-normality and heteroscedasticity of residuals.

To test H1, linear regression models compared responses to PH and SAPRO ads on the three motivation outcomes. Given we were most interested in the average effects of exposure to all PH ads compared with the average effects of exposure to all SAPRO ads (as opposed to the effectiveness of individual PH ads compared with individual SAPRO ads), we averaged each participant’s responses to the three ads they saw and used this average as a single value in analyses.

Complementing this main test of H1, we also conducted a post-hoc exploration of how the individual ads ranked in comparison to one another. For each motivation outcome, a multivariable linear regression model analysing data at the individual-ad level (ie, 8769 person ad ratings) was conducted, including a covariate for whether the participant had seen the ad before and adjusting for clustering at the individual level (ie, using participant identification number given each participant saw three ads). From these models, predicted marginal means were generated for each ad. The predicted means of all 111 ads (PH and SAPRO ads combined) were then ranked from highest to lowest. Fisher’s exact tests were then used to compare the proportion of ads from each condition that were ranked in the top 25%, the middle 50% and the bottom 25%, to indicate whether PH and SAPRO ads were over-represented or under-represented in the top 25% and bottom 25% of all ads for each outcome.

To test H2, logistic regression models compared differences in responses to PH and SAPRO ads on the three intention outcomes. To test H3, linear regression models compared differences on the two favourable perceptions of drinkers outcomes. H4 was tested using Pearson correlations between the favourable perceptions scales and the motivation and intention outcomes. To examine subgroup differences, an additional set of linear and logistic regression models for each outcome tested three interaction terms: condition*sex (RQ1a), condition*age (RQ1b), and condition*risky drinking status (RQ1c) (one interaction term per model).

Results

Participant demographic and drinking characteristics are presented in table 1. This sample was largely comparable in characteristics to the sample of weekly drinkers sourced from the 2013 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS), with the exception that the proportion of males in our sample (47.6%) was smaller and the proportion of 18 to 29 year olds (53.5%) was larger than in the NDSHS due to the use of sex and age quotas in recruitment (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and drinking characteristics of participants exposed to alcohol harm reduction advertisements (ads) developed by public health (PH) organisations or alcohol industry Social Aspects/Public Relations Organisations (SAPROs), compared with characteristics of weekly drinkers aged 18 to 64 in the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) 2013

| (n=2923) | (n=2174) | (n=749) | P value* | (n=8165) | |

| Overall | PH ads | SAPRO ads | NDSHS 2013 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Sex, % male | 47.6 | 47.9 | 46.6 | 0.54 | 58.4 |

| Age, % | 0.47 | ||||

| 18–29 years | 53.5 | 53.9 | 52.3 | 21.9 | |

| 30–64 years | 46.5 | 46.1 | 47.7 | 78.1 | |

| Education†, % tertiary completed | 69.3 | 69.8 | 68.0 | 0.35 | 71.6 |

| Parent or guardian of child(ren)‡, % | 43.3 | 43.4 | 43.0 | 0.85 | 45.7 |

| Location, % metropolitan | 67.6 | 67.8 | 67.0 | 0.70 | 70.1 |

| Socioeconomic status (SES)§, % | 0.99 | ||||

| Low SES (high disadvantage, 0%–40%) | 29.7 | 29.8 | 29.5 | 30.0 | |

| Mid SES (mid disadvantage, 41%–80%) | 43.9 | 43.9 | 43.8 | 44.0 | |

| High SES (low disadvantage, 81%–100%) | 25.6 | 25.5 | 25.8 | 26.0 | |

| Drinking characteristics | |||||

| High-risk drinkers, % | 49.0 | 49.0 | 49.0 | 1.00 | 53.5 |

| Number of days consumed alcohol in past week, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0 to 6.0) | 3.0 (2.0 to 6.0) | 4.0 (2.0 to 6.0) | 0.24 | n/a |

| Number of drinks in past week, median (IQR) | 8.0 (4.0 to 16.0) | 8.0 (4.0 to 16.0) | 8.0 (4.0 to 16.0) | 0.19 | n/a |

| Alcohol identity (5-point scale), mean (SD) | 2.7 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.1) | 0.48 | n/a |

| Ad exposure characteristics | |||||

| Number of ads seen from Australia, % | 0.10 | n/a | |||

| 0 | 22.7 | 23.7 | 19.9 | ||

| 1 | 43.8 | 43.6 | 44.5 | ||

| 2 | 28.6 | 27.7 | 31.1 | ||

| 3 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 4.5 | ||

| Number of ads seen before, % | <0.01 | n/a | |||

| 0 | 85.8 | 86.8 | 82.8 | ||

| 1 | 10.0 | 8.8 | 13.6 | ||

| 2 or 3 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 3.6 | ||

Recruitment quotas were applied to achieve approximately even numbers of men and women, and younger (18 to 29 years) and older (30 to 64 years) adults. n/a=data not available in the NDSHS 2013.

*P values from t-test (continuous variables), Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test (count variables), or χ2 test (categorical variables) comparing characteristics of participants who viewed PH ads with those of participants who viewed SAPRO ads.

†n=288 missing in NDSHS 2013 sample.

‡n=631 missing in NDSHS 2013 sample.

§n=25 (0.86%) missing in current study.

In all regression models, the ad familiarity covariate was a significant and positive predictor of the outcome, with participants who had previously seen 2+ of the three ads providing stronger responses on each outcome compared with those who had not previously seen any of the ads (there were no significant differences between those who had seen none and those who had seen just one ad before). Results provided partial support for H1 as motivation to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed was lower among participants who viewed SAPRO compared with PH ads (β=−0.091, 95% CI −0.171 to -0.010). However, there were no significant differences between conditions for motivation to behave responsibly/not get drunk and motivation to limit drinking around/never supply to minors, although the coefficients were in the expected direction (table 2). Furthermore, in post-hoc analyses that compared the proportion of PH and SAPRO ads that ranked in the top and bottom 25% of all ads, results from the Fisher’s exact test indicated an uneven distribution of ads (all p<0.0001; online supplemental appendix D). On all three motivation outcomes PH ads were distributed as expected (ie, across outcomes, between 24% and 28% of PH ads were ranked in the top 25% of all ads, and between 20% and 22% of PH ads were ranked in the bottom 25%). By comparison, on motivation to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed, SAPRO ads were under-represented in the top 25% (17%) and over-represented in the bottom 25% (39%; online supplemental appendix D). Similarly, SAPRO ads were over-represented in the bottom 25% on both motivation to behave responsibly/not get drunk (33%) and motivation to limit drinking around/never supply to minors (40%).

Table 2.

Comparison of the effect of exposure to alcohol harm reduction advertisements (ads) developed by public health (PH) organisations or alcohol industry Social Aspects/Public Relations Organisations (SAPROs)

| PH ads (n=2174) |

SAPRO ads (n=749) |

β (95% CI)* | P value | |

| Adj. mean | Adj. mean | |||

| Motivation to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed† | 3.15 | 3.06 | −0.091 (−0.171 to −0.010) | 0.027 |

| Motivation to behave responsibly/not get drunk† | 3.44 | 3.43 | −0.010 (−0.082 to 0.062) | 0.788 |

| Motivation to limit drinking around/never supply to minors† | 3.43 | 3.38 | −0.056 (−0.133 to 0.021) | 0.156 |

| Success-related favourable perceptions of drinkers | 3.95 | 3.97 | 0.019 (−0.060 to 0.097) | 0.641 |

| Fun-related favourable perceptions of drinkers | 4.29 | 4.38 | 0.095 (0.013 to 0.177) | 0.022 |

| Adj. percentage | Adj. percentage | OR (95% CI)* | ||

| Intention to avoid drinking alcohol completely | 25.5 | 20.8 | 0.77 (0.63 to 0.94) | 0.011 |

| Intention to reduce the number of drinking occasions | 50.7 | 48.4 | 0.91 (0.77 to 1.08) | 0.294 |

| Intention to reduce the amount of alcohol on each occasion | 52.4 | 47.5 | 0.82 (0.69 to 0.97) | 0.021 |

All models adjusted for the number of familiar ads seen by each participant. Bolded results are significant at p<0.05.

*Beta coefficients/ORs for the effect of exposure to SAPRO ads compared with PH ads.

†Motivation outcomes were the average of the scores given to the three ads seen by each participant, as described in the text.

Adj., adjusted for covariates.

H2 was also partly supported, as participants who viewed SAPRO ads had 23% lower odds of intending to avoid drinking alcohol completely (OR=0.77, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.94), and 18% lower odds of intending to reduce the amount of alcohol (OR=0.82, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.97). There was not a significant difference on intentions to reduce the number of drinking occasions although the effect was in the predicted direction (table 2).

Partially supporting H3, participants who viewed SAPRO ads reported more favourable fun-related perceptions of drinkers (β=0.095, 95% CI 0.013 to 0.177), but success-related perceptions of drinkers did not differ between the conditions (table 2). Contrary to H4, correlations between fun-related perceptions of drinkers and the motivation and intention outcomes were mostly negative and very small (ranging from −0.003 with intentions to reduce the number of drinking occasions to 0.005 with intentions to reduce the amount of alcohol on each occasion). Correlations between success-related perceptions of drinkers and the motivation and intention outcomes were also very small, ranging between −0.052 (intentions to reduce the number of drinking occasions) and 0.002 (intentions to avoid drinking alcohol completely).

None of the 24 interaction tests by sex (RQ1a), age (RQ1b) and risky drinking status (RQ1c) was significant at p<0.05 (online supplemental appendix E), indicating consistent differences in responses to PH and SAPRO ads across subgroups.

Discussion

Summary of findings

In this experimental study, compared with drinkers exposed to three PH ads, those exposed to three SAPRO ads reported significantly lower motivation to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed, intentions to avoid drinking alcohol completely in the next week and intentions to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed on each occasion over the next week, providing partial support for H1 and H2. In addition, they reported more favourable fun-related perceptions of people who drink (partially supporting H3) although contrary to H4, fun-related perceptions (and success-related perceptions) were not meaningfully correlated with the motivation and intention outcomes. Exposure to PH versus SAPRO ads did not yield significant differences in motivation to behave responsibly, motivation to limit drinking around/never supply to minors, intentions to reduce the number of drinking occasions over the next week or success-related perceptions of people who drink, although for most of these outcomes the effect was in the predicted direction. Subgroup analyses indicated that this pattern of findings was largely consistent across sex, age and risky drinking subgroups. In addition, when we ranked all 111 ads (PH and SAPRO ads combined), and grouped ads according to whether they were in the top 25%, middle 50% or bottom 25% of all 111 advertisements, we found that SAPRO ads were under-represented in the top 25% on motivation to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed and over-represented in the bottom 25% on all three motivation measures.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to experimentally compare the effectiveness of alcohol harm reduction advertisements funded by PH organisations and the alcohol industry. One study strength is that exposure to all ads occurred in a consistent way with random assignment of participants. Another strength is the inclusion of all eligible PH and SAPRO ads identified at the time of study development, which means the findings provide a comprehensive and unbiased assessment of the effects of ads produced by PH agencies and alcohol industry SAPROs. However, one consequence of including all available ads was that there was a much larger number of PH than SAPRO ads identified, such that for the motivation outcomes measured after each ad, the range of scores was broader for the 83 PH ads than for the 28 SAPRO ads (data not presented). This variation between conditions in the range of scores may have contributed to the small effect sizes for the motivation outcomes. Our use of eight outcome measures—three for H1, three for H2 and two for H3—may mean that some of the significant effects are due to chance. At the same time, for seven of the eight outcomes, the difference in means and proportions between the two ad conditions was in the expected direction; this pattern increases our confidence in the validity of these findings.

An important limitation is the absence of a control condition, which means we cannot claim that SAPRO ads were ineffective, or conversely that PH ads were effective. Further research is needed to more rigorously test the proposition that SAPRO ads have the potential to cause harm by comparing responses among individuals exposed to these ads with those not exposed to any alcohol harm reduction messaging. An additional limitation is that our study focussed on ads developed by alcohol industry SAPROs but did not include ads produced by individual alcohol companies or other types of industry bodies. This was largely because in Australia, as elsewhere, the bulk of recent activity from the alcohol industry has been led by the SAPRO DrinkWise.45 The ads used in this study were all produced prior to 2014, and data were collected in 2015. Although the media landscape has evolved rapidly in the past 5 years, with increased use of online streaming platforms and reductions in some age groups in time spent watching broadcast television,46 our findings that PH and SAPRO ads differ in their relative effectiveness are relevant irrespective of whether the ads are to be seen on broadcast television or digital media. Furthermore, investment from the alcohol industry in alcohol harm reduction education has continued in recent years: for example, AB InBev—the world’s largest beer manufacturer—has committed US$1 billion over 10 years for dedicated social marketing campaigns to, among other things, influence social norms and individual behaviours to reduce harmful alcohol use;47 and both Drinkaware UK48 and DrinkWise Australia,49 for example, have continued to develop new campaigns.

Finally, although our sample had a similar composition to the national benchmark sample in terms of education, parental status, metropolitan versus regional location, socioeconomic status and the measure of high-risk drinking, our use of quotas for sex and age meant that our sample was comprised of fewer men and more 18 to 29 year olds than would be expected in the national population of weekly drinkers. Online non-probability panels do not provide a random population sample, and so we do not suggest our parameter estimates statistically represent the national population of people who drink. However, the patterns of responses to PH and SAPRO ads observed in this large and diverse sample are likely to reflect those in the population, particularly given that our exploratory analyses indicated that responses across subgroups were largely consistent.

Implications for public health

Overall, these results suggest that governments and PH organisations should remain cautious about allowing alcohol industry SAPROs to develop and disseminate alcohol harm reduction ads. However, in considering these findings we note that even when differences between the PH and SAPRO ads were statistically significantly, effect sizes were small. This is not uncommon in message testing studies where forced exposure designs mean each participant views a small number of ads a small number of times. When these types of ads are used in real world campaigns they are typically broadcast over multiple media, reaching large segments of the population numerous times. Therefore, even the small differences observed in this limited exposure experimental study signal the possibility of large and meaningful differences in effectiveness at the population level when ads are broadcast in mass-reach multimedia campaigns.50 Furthermore, the effect sizes observed in this study are comparable with those from one previous campaign evaluation study and one controlled experiment that used similar intention measures as outcomes.28 32 In their evaluation of a mass media campaign focussed on the link between alcohol and cancer, Dixon and colleagues28 found that intentions to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed increased by between 3.4 and 10.5 percentage points from before to after the campaign (at first and second follow-up, respectively) among those who consumed more than two drinks per day, compared with a 5.2 percentage point difference in intentions to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed on each occasion between those exposed to PH and SAPRO ads in the current study. Similarly, in Wakefield et al’s study in which the effects of exposure to two PH ads about either the short-term harms or long-term harms of alcohol were compared with a non-alcohol related advertising control condition, comparable effect sizes for the measure of intentions to avoid alcohol completely were observed as in our comparison of PH and SAPRO ads (5.1 percentage points in the current study compared with 6.4 to 7.3 percentage points for long-term harm ads, and 6.2 to 6.3 percentage points for the short-term harm ads in the Wakefield et al study32). These comparisons further increase our confidence that the small effects observed in this study have practical significance.

Compared with those who saw PH ads, drinkers exposed to SAPRO ads were less motivated to reduce their drinking and less likely to intend to reduce their consumption. In addition, exposure to SAPRO ads evoked stronger perceptions that people who drink are fun, although contrary to our predictions, fun-related perceptions of drinkers (and success-related perceptions) were not meaningfully correlated with the motivation and intention outcomes. These small correlations suggest that there are other characteristics—besides positive portrayals of people who drink—that contribute to the relative ineffectiveness of SAPRO ads at generating motivation and intentions to drink less. On the whole though, this pattern of findings suggests that SAPRO ads are more likely than PH ads to present alcohol and drinking in a favourable light, rather than highlighting the negative consequences of alcohol consumption. This is consistent with DeJong et al’s audit of industry-funded responsible drinking advertisements, which found these used similar scenes, themes and visuals as in alcoholic product advertisements.21 It is also consistent with the findings of Pettigrew et al’s study of DrinkWise Australia’s ‘How To Drink Properly’ campaign (included in the SAPRO condition in the current study), in which many young adults felt that the ad encouraged drinking through its repetitive use of images of alcohol consumption which implied that alcohol enhances social interactions and can be enjoyed in a fun environment.23

SAPRO ads were over-represented in the bottom 25% of all ads on motivation to behave responsibly/not get drunk, despite the fact that many SAPROs describe their mission as primarily being to promote responsible drinking.15 Several PH scholars have described the problems with such mission statements due to (i) the emphasis they place on drinkers’ behaviour rather than the amount consumed as the cause of alcohol-related harm, (ii) the failure to clearly define what is meant by ‘responsible drinking’ and (iii) a de-emphasis of the critical role of government action in promoting reduced consumption.24 25 51–53 It is also notable that voluntary ‘Drink Responsibly’ slogans frequently appear in alcohol advertisements, although more often than not these slogans are written in such a way that they appear more like a promotion for the product than a true ‘responsible drinking’ message.54 Our results suggest that, despite SAPROs’ claims that their ads promote responsible drinking behaviour, there is no evidence that their ads are more effective in this regard than ads created by PH organisations.

Overall, these findings suggest that alcohol-industry SAPROs may not be following best practice principles when developing alcohol harm reduction campaigns, may not be pre-testing these campaigns adequately, and may not be conducting appropriate evaluation.13 In Australia, for example, campaigns developed by DrinkWise Australia have been subject to little publicly available evaluation: the DrinkWise website contains only minimal top line evaluation findings for the first three of its campaigns, and nothing for the more recent ‘You Won’t Miss a Moment If You DrinkWise’ campaign.55 Furthermore, a recent review of industry-funded drink driving prevention initiatives found that only 3% were evaluated using appropriate outcomes.56 Another recent review of alcohol industry corporate social responsibility activities found the vast majority did not demonstrate they reduced harmful drinking.11 These findings suggest that if alcohol-industry SAPROs are to play a role in disseminating public education messages, then at the very least governments should require that they provide evidence of having used best practice formative and evaluative research practices.

Future research

Ongoing research is required to build greater understanding of the characteristics of PH alcohol harm reduction ads that contribute most to their effectiveness,31 32 as well as to identify the message features that promote favourable perceptions of people who drink and so should be avoided in PH and SAPRO ads, and the features that mean some SAPRO ads may be more or less effective than others. One characteristic that is likely to be particularly important is whether the ad refers to serious long-term health consequences of drinking, including cancer. There is some evidence that PH ads31 and warning labels for alcohol containers57 58 that focus on cancer may be particularly effective, but the alcohol industry has a history of misrepresenting the evidence linking alcohol with cancer.18 59 Future research is required to determine the impact of cancer messaging overall, and when it comes from PH versus industry-sponsored sources. At the same time, the findings from the present study indicate that continued attention to the potential risks arising from alcohol industry involvement in alcohol harm reduction efforts is warranted. Similar studies should be conducted in other countries to explore similarities and differences in drinkers’ responses.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify and comparatively evaluate a large pool of alcohol harm reduction ads developed by PH agencies with those developed by alcohol industry SAPROs. It provides the most rigorous assessment to date of the potential (in)effectiveness of SAPRO-produced campaigns. The results indicate that although the alcohol industry has a sophisticated understanding of how to create persuasive alcohol advertisements,23 54 and claims by some SAPROs that they are evidence-based,60 the alcohol harm reduction ads produced by SAPROs have not been as effective at generating motivation and intentions to reduce alcohol consumption as those developed by PH agencies. Rather, these ads may lead to more positive perceptions of people who drink alcohol.

These results suggest that policymakers need to question whether there is a role for alcohol industry SAPROs in alcohol harm reduction efforts.16 17 61 62 There is an inherent conflict of interest in the alcohol industry developing campaigns that, if effective, could reduce alcohol industry profits.15 At the very least, these results suggest that care should be taken to ensure that any activities undertaken by SAPROs do not supplant or replace effort or funding by governments and PH agencies.17 To reduce the PH burden attributable to alcohol, there is a need for public education that motivates people to change their behaviour. Our study results suggest that this goal will best be served by funding and disseminating alcohol harm reduction campaigns developed by PH organisations.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: EB, MAW and KD designed the study, with input from SJD, HGD, MDS and SP. KD managed data collection. DAJMS analysed the data. DAJMS, EB and SJD interpreted the findings, with input from all other authors. EB and DAJMS drafted the manuscript, with critical feedback from all other authors. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council under Project Grant #1070689 and by Cancer Council Victoria.

Competing interests: EB, SJD, KD, HGD and MAW report grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, during the conduct of the study. EB, SJD, KD, HGD and MAW are employed by a non-profit organisation that conducts public health interventions and advocacy aimed at reducing alcohol-related health harms in the community, especially those pertaining to cancer. SP reports funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council to conduct alcohol-control research, and she is a non-executive director of the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from Cancer Council Victoria’s Institutional Research Review Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. . A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2224–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/274603/9789241565639-eng.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 29 Oct 2019].

- 3.White V, Faulkner A, Coomber K, et al. . How has alcohol advertising in traditional and online media in Australia changed? Trends in advertising expenditure 1997-2011. Drug Alcohol Rev 2015;34:521–30. 10.1111/dar.12286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth Alcohol advertising and youth fact sheet, 2010. Available: http://www.camy.org/resources/fact-sheets/alcohol-advertising-and-youth/ [Accessed 29 Oct 2019].

- 5.Jones SC, Hall S, Kypri K. Should I drink responsibly, safely or properly? Confusing messages about reducing alcohol-related harm. PLoS One 2017;12:e0184705. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrelly MC, Healton CG, Davis KC, et al. . Getting to the truth: evaluating national tobacco countermarketing campaigns. Am J Public Health 2002;92:901–7. 10.2105/AJPH.92.6.901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakefield M, Terry-McElrath Y, Emery S, et al. . Effect of televised, tobacco company-funded smoking prevention advertising on youth smoking-related beliefs, intentions, and behavior. Am J Public Health 2006;96:2154–60. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henriksen L, Dauphinee AL, Wang Y, et al. . Industry sponsored anti-smoking ads and adolescent reactance: test of a boomerang effect. Tob Control 2006;15:13–18. 10.1136/tc.2003.006361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson P. The beverage alcohol industry's social aspects organizations: a public health warning. Addiction 2004;99:1376–7. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00866.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCambridge J, Kypri K, Miller P, et al. . Be aware of Drinkaware. Addiction 2014;109:519–24. 10.1111/add.12356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babor TF, Robaina K, Brown K, et al. . Is the alcohol industry doing well by 'doing good'? Findings from a content analysis of the alcohol industry's actions to reduce harmful drinking. BMJ Open 2018;8:e024325. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casswell S. Vested interests in addiction research and policy. why do we not see the corporate interests of the alcohol industry as clearly as we see those of the tobacco industry? Addiction 2013;108:680–5. 10.1111/add.12011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones SC, Wyatt A, Daube M. Smokescreens and beer goggles: how alcohol industry CSM protects the industry. Soc Mar Q 2015;22:264–79. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babor T, Hall W, Humphreys K, et al. . Who is responsible for the public's health? The role of the alcohol industry in the WHO global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. Addiction 2013;108:2045–7. 10.1111/add.12368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casswell S, Callinan S, Chaiyasong S, et al. . How the alcohol industry relies on harmful use of alcohol and works to protect its profits. Drug Alcohol Rev 2016;35:661–4. 10.1111/dar.12460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daube M. Protecting their paymasters. Addiction 2014;109:526–7. 10.1111/add.12416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hastings G, Angus K. When is social marketing not social marketing? J Soc Mark 2011;1:45–53. 10.1108/20426761111104428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petticrew M, Maani Hessari N, Knai C, et al. . How alcohol industry organisations mislead the public about alcohol and cancer. Drug Alcohol Rev 2018;37:293–303. 10.1111/dar.12596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim AWY, van Schalkwyk MCI, Maani Hessari N, et al. . Pregnancy, fertility, breastfeeding, and alcohol consumption: an analysis of framing and completeness of information disseminated by alcohol industry-funded organizations. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2019;80:524–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mialon M, McCambridge J. Alcohol industry corporate social responsibility initiatives and harmful drinking: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health 2018;28:664–73. 10.1093/eurpub/cky065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeJong W, Atkin CK, Wallack L. A critical analysis of "moderation" advertising sponsored by the beer industry: are "responsible drinking" commercials done responsibly? Milbank Q 1992;70:661–78. 10.2307/3350215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavack AM. Message content of alcohol moderation TV commercials. Health Mark Q 1999;16:15–31. 10.1300/J026v16n04_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettigrew S, Biagioni N, Daube M, et al. . Reverse engineering a 'responsible drinking' campaign to assess strategic intent. Addiction 2016;111:1107–13. 10.1111/add.13296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atkin JL, McCardle M, Newell SJ. The role of advertiser motives in consumer evaluations of ‘responsibility’ messages from the alcohol industry. Journal of Marketing Communications 2008;14:315–35. 10.1080/13527260802141447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barry AE, Goodson P. Use (and misuse) of the responsible drinking message in public health and alcohol advertising: a review. Health Educ Behav 2010;37:288–303. 10.1177/1090198109342393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith SW, Atkin CK, Roznowski J. Are "drink responsibly" alcohol campaigns strategically ambiguous? Health Commun 2006;20:1–11. 10.1207/s15327027hc2001_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisenberg EM. Ambiguity as strategy in organizational communication. Commun Monogr 1984;51:227–42. 10.1080/03637758409390197 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dixon HG, Pratt IS, Scully ML, et al. . Using a mass media campaign to raise women's awareness of the link between alcohol and cancer: cross-sectional pre-intervention and post-intervention evaluation surveys. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006511. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin N, Buykx P, Shevills C, et al. . Population level effects of a mass media alcohol and breast cancer campaign: a cross-sectional pre-intervention and post-intervention evaluation. Alcohol Alcohol 2018;53:31–8. 10.1093/alcalc/agx071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stautz K, Marteau TM. Viewing alcohol warning advertising reduces urges to drink in young adults: an online experiment. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1–10. 10.1186/s12889-016-3192-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wakefield MA, Brennan E, Dunstone K, et al. . Features of alcohol harm reduction advertisements that most motivate reduced drinking among adults: an advertisement response study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014193. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wakefield MA, Brennan E, Dunstone K, et al. . Immediate effects on adult drinkers of exposure to alcohol harm reduction advertisements with and without drinking guideline messages: experimental study. Addiction 2018;113:1019–29. 10.1111/add.14147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Australian Government Department of Health Alcohol laws in Australia, 2020. Available: https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/alcohol/about-alcohol/alcohol-laws-in-australia [Accessed 26 Feb 2020].

- 34.Dunstone K, Brennan E, Slater MD, et al. . Alcohol harm reduction advertisements: a content analysis of topic, objective, emotional tone, execution and target audience. BMC Public Health 2017;17:312. 10.1186/s12889-017-4218-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suresh K. An overview of randomization techniques: an unbiased assessment of outcome in clinical research. J Hum Reprod Sci 2011;4:8–11. 10.4103/0974-1208.82352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.Noar SM, Bell T, Kelley D, et al. . Perceived message effectiveness measures in tobacco education campaigns: a systematic review. Commun Methods Meas 2018;12:295–313. 10.1080/19312458.2018.1483017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brennan E, Durkin SJ, Wakefield MA, et al. . Assessing the effectiveness of antismoking television advertisements: do audience ratings of perceived effectiveness predict changes in quitting intentions and smoking behaviours? Tob Control 2014;23:412–8. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheeran P. Intention-behaviour relations: a conceptual and empirical review : Stroebe W, Hewstone M, Eur Rev Soc Psychol. London: Wiley, 2002: 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Webb TL, Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull 2006;132:249–68. 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) National Drug Strategy Household Survey detailed report 2013. Canberra, Australia: AIHW, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia, 2009. Available: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/australian-guidelines-reduce-health-risks-drinking-alcohol [Accessed 28 Feb 2020].

- 42.Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, et al. . Reliability of a timeline method: assessing normal drinkers' reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br J Addict 1988;83:393–402. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Australian Bureau of Statistics Technical paper: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) 2011. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013. Available: http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/22CEDA8038AF7A0DCA257B3B00116E34/$File/2033.0.55.001%20seifa%202011%20technical%20paper.pdf [Accessed 29 Oct 2019].

- 44.StataCorp Stata statistical software: release 14.2. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brennan E, Wakefield MA, Durkin SJ, et al. . Public awareness and misunderstanding about DrinkWise Australia: a cross-sectional survey of Australian adults. Aust N Z J Public Health 2017;41:352–7. 10.1111/1753-6405.12674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Durkin S, Wakefield M. CBRC Research Paper Series No. 49: media use and trends and implications for potential reach of public education and motivation campaigns: application to tobacco control. Melbourne, Australia: Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer, Cancer Council Victoria, 2018. Available: https://www.cancervic.org.au/downloads/cbrc_research_papers/CBRC_RPS_No.49.pdf [Accessed 14 Apr 2020].

- 47.Anderson P, Rehm J. Evaluating alcohol industry action to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol 2016;51:383–7. 10.1093/alcalc/agv139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drinkaware Our campaigns, 2020. Available: https://www.drinkaware.co.uk/about-us/our-campaigns/ [Accessed 14 Apr 2020].

- 49.DrinkWise Australia You won't miss a moment if you DrinkWise, 2020. Available: https://drinkwise.org.au/our-work/you-wont-miss-a-moment-if-you-drinkwise-2/# [Accessed 14 Apr 2020].

- 50.Snyder LB, Hamilton MA, Mitchell EW, et al. . A meta-analysis of the effect of mediated health communication campaigns on behavior change in the United States. J Health Commun 2004;9:71–96. 10.1080/10810730490271548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moss AC, Albery IP. The science of absent evidence: is there such thing as an effective responsible drinking message? Alcohol Alcohol 2018;53:26–30. 10.1093/alcalc/agx070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petticrew M, Fitzgerald N, Durand MA, et al. . Diageo's 'Stop Out of Control Drinking' campaign in Ireland: an analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0160379. 10.1371/journal.pone.0160379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maani Hessari N, Petticrew M. What does the alcohol industry mean by ‘Responsible drinking’? A comparative analysis. J Public Health 2018;40:90–7. 10.1093/pubmed/fdx040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith KC, Cukier S, Jernigan DH. Defining strategies for promoting product through 'drink responsibly' messages in magazine ads for beer, spirits and alcopops. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;142:168–73. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DrinkWise Australia Campaigns, 2019. Available: https://drinkwise.org.au/#q=campaigns&r=true [Accessed 29 Oct 2019].

- 56.Esser MB, Bao J, Jernigan DH, et al. . Evaluation of the evidence base for the alcohol industry's actions to reduce drink driving globally. Am J Public Health 2016;106:707–13. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.303026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vallance K, Romanovska I, Stockwell T, et al. . "We Have a Right to Know": exploring consumer opinions on content, design and acceptability of enhanced alcohol labels. Alcohol Alcohol 2018;53:20–5. 10.1093/alcalc/agx068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pettigrew S, Jongenelis M, Chikritzhs T, et al. . Developing cancer warning statements for alcoholic beverages. BMC Public Health 2014;14:786. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maani Hessari N, van Schalkwyk M, Thomas S, et al. . Alcohol industry CSR organisations: what can their Twitter activity tell us about their independence and their priorities? A comparative analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:892 10.3390/ijerph16050892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DrinkWise Australia About, 2019. Available: https://drinkwise.org.au/about-us/about/# [Accessed 29 Oct 2019].

- 61.McCambridge J, Mialon M, Hawkins B. Alcohol industry involvement in policymaking: a systematic review. Addiction 2018;113:1571–84. 10.1111/add.14216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McKee M, Stuckler D. Revisiting the corporate and commercial determinants of health. Am J Public Health 2018;108:1167–70. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035569supp001.pdf (211.4KB, pdf)