Abstract

Objective

Lyme disease is a tick-borne, multisystemic disease caused by Borrelia burgdorferi. Standard treatments for early Lyme disease include short courses of oral antibiotics but relapses often occur after discontinuation of treatment. Several studies have suggested that ongoing symptoms may be due to a highly antibiotic resistant form of B. burgdorferi called biofilms. Our recent clinical study reported the successful use of an intracellular mycobacterium persister drug used in treating leprosy, diaminodiphenyl sulfone (dapsone), in combination therapy for the treatment of Lyme disease. In this in vitro study, we evaluated the effectiveness of dapsone individually and in combination with cefuroxime and/or other antibiotics with intracellular activity including doxycycline, rifampin, and azithromycin against Borrelia biofilm forms utilizing crystal violet biofilm mass, and dimethyl methylene blue glycosaminoglycan assays combined with Live/Dead fluorescent microscopy analyses.

Results

Dapsone, alone or in various combinations with doxycycline, rifampin and azithromycin produced a significant reduction in the mass and protective glycosaminoglycan layer and overall viability of B. burgdorferi biofilm forms. This in vitro study strongly suggests that dapsone combination therapy could represent a novel and effective treatment option against the biofilm form of B. burgdorferi.

Keywords: Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, Biofilm, Dapsone

Introduction

Lyme disease is the number one vector-borne illness in the United States caused by B. burgdorferi species and transmitted via the bite of Ixodes ticks [1–3]. Successful frontline treatments for early Lyme disease involve using antibiotics including doxycycline, amoxicillin, cefuroxime axetil, and ceftriaxone [4–7]. Although standard antibiotic therapy is effective in most cases of early Lyme disease [5], CDC reports suggest that greater than 10–20% of Lyme patients who have been treated for an Erythema migrans (EM) rash, a classical early manifestation of Lyme disease, continue to experience symptoms of fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and cognitive impairment despite appropriate treatment [8–13].

Several theories to explain persistent symptoms have been suggested, including immune evasion in privileged sites [14], antigenic variation [15], persistent antigenic stimulation [16], biofilm formation [17, 18] and B. burgdorferi persister cells, a highly resistant bacterial form which may protect the bacteria from antibacterial therapy. B. burgdorferi can exist in spirochetal, round body forms, intracellularly, as well as in newly discovered biofilm forms [4, 19–29]. Previous data suggested that standard and some newly discovered antibiotics for Lyme disease can be very effective in eliminating spirochetal, round body, intracellular and antibiotic tolerant persister cells [4, 20, 25–27] but have little effect on biofilm forms [24, 30]. Persisters are multi-drug tolerant cells present in significant numbers in biofilms [27, 29], and the importance of Borrelia biofilms has been highlighted in autopsy tissues from a well-documented Lyme disease patient [31]. Therefore, to successfully treat Lyme disease, there is an urgent need to find an agent or combination of antimicrobial agents which can efficiently eliminate resistant biofilm forms of B. burgdorferi.

Dapsone combination therapy (DDS CT) is clinically effective as a novel drug regimen for the treatment of chronic Lyme disease as reported in 100 patients who had previously failed commonly prescribed antibiotic therapies [32]. A recent retrospective study among a larger group of 200 patients also found that dapsone (DDS) combined with other intracellular antibiotics including doxycycline, rifampin, and/or azithromycin was effective in reducing 8 major Lyme disease symptoms [33, 34]. Although dapsone combination therapy was clinically effective, its efficacy against different morphological forms of B. burgdorferi in culture had not yet been fully studied. In a previous 2017 study, Feng et al. compared the efficacy of sulfa drugs including dapsone, sulfamethoxazole, sulfachlorpyridazine, and assessed their combinations along with commonly prescribed Lyme antibiotics for their activity against B. burgdorferi “persisters” and found that dapsone was the most active drug among the 3 sulfa drugs [35]. However, this study did not evaluate the effect of any of the sulfa drugs on attached B. burgdorferi biofilm. We therefore designed an in vitro study using dapsone as a single drug and/or in combination with cefuroxime axetil and/or other antibiotics with intracellular activity including doxycycline, rifampin and azithromycin in order to find the most effective combinations to effectively eliminate resistant biofilm forms of Borrelia burgdorferi.

Main text

Methods

Bacteria culture conditions

Low passage isolates of B. burgdorferi, B31 strain were obtained from ATCC (#35,210, Manassas, VA) and cultured in Barbour-Stoner-Kelly H (BSK-H) media (Sigma, St Louis, MO) supplemented with 6% rabbit serum (Pel-Freez®, Rogers, AR). The stock cultures were maintained in sterile 15 ml glass tubes and incubated at 33 °C with 5% CO2 in the absence of antibiotics. Spirochetes for surface attached biofilms were seeded at 5 × 106 cells/ml in 4-well Permanox chamber slides (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) or in 48-well sterile tissue culture plates (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for 5 days to establish attached biofilm form. Floating spirochetal cells and aggregates from the supernatant were removed to ensure only surface attached biofilms would be analyzed.

Antibiotics

All antibiotics were prepared in standard 1 × phosphate buffered saline solution (PBS) and sterilized using 0.2 µm filter unit (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). As a negative control, 1 × PBS was used which was the diluent for antimicrobial compounds studied.

Crystal violet biofilm, Baclight LIVE/DEAD viability, Dimethylmethylene blue glycosaminoglycan (DMMB) assays.

The effect of the antimicrobial agents on B. burgdorferi biofilm mass and viability was evaluated by using a crystal violet assay and LIVE/DEAD microscopic analyses respectively as described earlier [30]. The effectiveness of the antibiotic combinations on the B. burgdorferi biofilms was also determined by quantifying the biofilm polysaccharide matrix content, glycosaminoglycans (GAG) as described [36].

Statistical analysis

Quantitative results were analyzed using the median value of all the readings from antimicrobial screens in addition to a two-tailed Student’s t -test (Microsoft Excel, Redmond, WA, USA). All experiments were performed a minimum of five independent times with at least four replicates per each experimental condition (N = 20). Each experiment was repeated by two different scientists (GG and KM) and statistical analyses were conducted independently by a third (ES).

Results

In this study, we compared and evaluated the antimicrobial effect of dapsone along with the other clinically tested antibiotics (doxycycline, rifampin, azithromycin, cefuroxime) on the growth and viability of attached B. burgdorferi biofilms using standard crystal violet biofilm mass and dimethylmethylene blue glycosaminoglycan assays combined with BacLight Live/Dead microscopic analysis. As in the previous studies from our group and others [30, 35], we tested two different antibiotic concentrations (10 µM and 50 µM) against attached B. burgdorferi biofilm structures. The 10 µM in vitro concentration corresponds well to the achievable serum level after administration of the antibiotics tested in this study [37–41]. Recent studies showed however that higher 50 µM concentrations for these antibiotics could be very effective against persister cells [27, 35], therefore this higher concentration was also tested.

First, the effectiveness of the single and combination antibiotic treatments on attached Borrelia biofilm was quantified by crystal violet biofilm mass assay after 72 h treatments with various antibiotics. The most significant results were achieved with individual and combination treatments with dapsone, as listed in Table 1. The best reduction in biofilm mass by a single antibiotic was achieved with dapsone at 10 µM and 50 µM concentrations resulting in 69% and 58% residual viability respectively, when compared to the PBS treated control (p value < 0.01). Rifampin at both 10 µM and 50 µM concentrations also resulted in a significant decrease in biofilm mass (76% and 60% respectively, p values < 0.01) compared to the PBS treated negative control samples, although not quite as effective as dapsone alone at comparable concentrations. Treatments with other single antibiotics including doxycycline, cefuroxime, and azithromycin were less effective and, in some cases, even increased biofilm size when compared to the PBS treated control (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of different antibiotic treatments on attached B. burgdorferi biofilm mass at 10 µM and 50 µM concentration evaluated with crystal violet biofilm assay after 72 h

| Antibiotics single | 10 µM residual % ± %SD | 50 µM residual % ± %SD | Antibiotics dual combinations | 10 µM residual % ± %SD | 50 µM residual ± %SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (PBS) | 100% | 100% | Control (PBS) | 100% | 100% |

| DDS | 69% ± 5.1 | 58% ± 4.7 | DDS + DOXY | 68% ± 5.3 | 65% ± 4.6 |

| DOXY | 107% ± 8.2 | 103% ± 11.6 | DDS + RIF | 82% ± 7.6 | 71% ± 5.6 |

| RIF | 76% ± 4.3 | 60% ± 8.9 | DDS + AZ | 106% ± 9.1 | 93% ± 7.3 |

| CEF | 109% ± 8.6 | 102% ± 9.5 | DDS + CEF | 83% ± 7.3 | 101% ± 10.3 |

| AZ | 101% ± 7.4 | 91% ± 7.9 | DOXY + RIF | 73% ± 5.8 | 74% ± 6.5 |

| Antibiotics triple combinations | 10 µM residual % ± %SD | 50 µM residual % ± %SD | Antibiotics quadruple combinations | 10 µM residual % ± %SD | 50 µM residual % ± %SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (PBS) | 100% | 100% | Control (PBS) | 100% | 100% |

| DDS + DOXY + RIF | 78% ± 5.8 | 52% ± 4.1 | DDS + DOXY + RIF + CEF | 72% ± 5.2 | 79% ± 6.2 |

| DDS + DOXY + CEF | 65% ± 4.2 | 60% ± 8.8 | DDS + DOXY + RIF + AZ | 78% ± 5.4 | 58% ± 3.5 |

| DDS + DOXY + AZ | 80% ± 7.7 | 72% ± 6.5 | DDS + RIF + AZ + CEF | 81% ± 6.8 | 68% ± 5.5 |

| DDS + RIF + AZ | 69% ± 4.2 | 77% ± 8.5 | DOX + RIF + AZ + CEF | 98% ± 8.5 | 82% ± 5.1 |

| DDS + RIF + CEF | 70% ± 5.6 | 62% ± 5.6 |

Table summarizes the mean % of residual viability with ± SD compared to the PBS treated control. N = 20

DDS dapsone, DOXY doxycycline, RIF rifampin, CEF cefuroxime, AZ azithromycin

The most effective dual combination was dapsone + doxycycline at both 10 µM and 50 µM concentrations (68% and 65% residual viability respectively) significantly decreasing biofilm size compared to the PBS treated control (p value < 0.01; Table 1). However, when compared to dapsone alone treated samples, this dual combination was not more effective than dapsone alone (p value > 0.05).

The triple combination treatment of dapsone + doxycycline + rifampin (52% residual viability) and quadruple combination of dapsone + doxycycline + rifampin + azithromycin (58% residual viability) treatments both at 50 µM concentration were the most effective when compared to the PBS treated control (p values < 0.01), however, the effect of three and four drug combinations at 50 µM was not significantly better than the 50 µM concentration treatments of dapsone alone or dapsone + doxycycline (p values > 0.05).

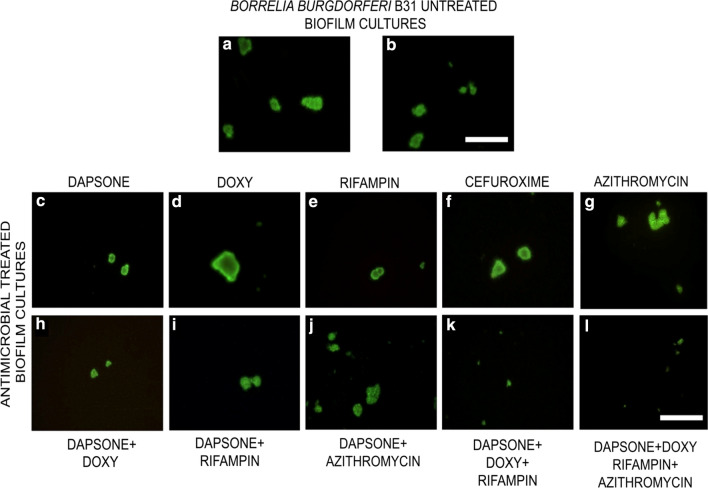

Crystal violet biofilm assay only measures the cellular mass (both live or dead) and does not provide information about the viability and the individual sizes of the antibiotic treated biofilm aggregates. Therefore, Live/Dead fluorescent microscopy techniques were used to visualize the effect of the most effective single and combination treatments after 72 h with different antibiotics and represented images are presented in Fig. 1. Biofilm cultures treated only with PBS show live (green) and compact morphology (Fig. 1a, b). For single and dual antibiotic treatments, the microscopy data were in good agreement with the crystal violet data. For example, it confirmed that single treatment dapsone (Fig. 1c) and dual treatment dapsone + doxycycline (Fig. 1h) were indeed effective in reducing Borrelia biofilm size, resulting in very small aggregates (less than 20 µm aggregates [Fig. 1c]).

Fig. 1.

Representative Live/Dead images of the attached B. burgdorferi biofilms following a 72 h treatment with different antimicrobial agents at 10 µM. Biofilms were analyzed by LIVE/DEAD assay as outlined in the Methods and representative images were taken at 100X magnification. Scale bar: 100 μm

However, for triple and quadruple antibiotic treatments, such as dapsone + doxycycline + rifampin and dapsone + doxycycline + rifampin + azithromycin, the microscopy images suggest a more significant effect of these triple and quadruple combinations than dapsone or dapsone + doxycycline as demonstrated by very small (less than 10 µm) and disorganized biofilms structures (Fig. 1k, l).

In order to further evaluate the effectiveness of the antibiotics on the attached biofilm form of B. burgdorferi, the amount of the protective layers of biofilm polysaccharide matrix of these aggregates were measured using the DMMB glycosaminoglycan (GAG) assay before and after 72 h antibiotic treatments. Biofilms treated with negative control, PBS, showed no reduction in the amounts of GAG, when compared with the untreated biofilm control. The most significant results with the different single and combination of antibiotics are summarized in Table 2. Single antibiotic treatments at 10 µM of rifampin and doxycycline were the most effective resulting in 75% and 76% residual GAG amounts compared to the PBS treated control (p value < 0.01). However, at 50 µM, dapsone showed the most significant effects with 68% residual GAG amounts of Borrelia biofilm compared to the untreated control (p value < 0.01). For combination therapies, dapsone + doxycycline + rifampin at 10 µM and dapsone + doxycycline + rifampin + azithromycin at 50 µM were the most effective agents when compared with the untreated control with 69% and 62% residual GAG amounts respectively. The 50 µM quadruple combination data were found to be significant not just in comparison to the negative control but to any single treatment result (p value < 0.05).

Table 2.

Effect of different antibiotic treatments on attached B. burgdorferi biofilm glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content at 50 µM concentration evaluated with Dimethylmethylene Blue Assay for Glycosaminoglycan after 72 h

| Antibiotics | 10 µM GAG % ± %SD | 50 µM GAG % ± %SD |

|---|---|---|

| Control (PBS) | 100% | 100% |

| DDS | 79% ± 5.8 | 68% ± 3.6 |

| DOXY | 76% ± 4.2 | 73% ± 7.2 |

| RIF | 75% ± 6.3 | 70% ± 5.8 |

| CEF | 78% ± 5.2 | 76% ± 7.4 |

| AZ | 82% ± 6.6 | 79% ± 8.2 |

| DDS + DOXY | 70% ± 8.2 | 69% ± 5.3 |

| DDS + DOXY + RIF | 69% ± 4.2 | 70% ± 7.3 |

| DDS + DOXY + RIF + AZ | 75% ± 6.8 | 62% ± 5.4 |

The table summarizes that mean % of the residual GAG amounts with ± SD compared to the PBS treated control. N = 20

DDS dapsone, DOXY doxycycline, RIF rifampin, CEF cefuroxime, AZ azithromycin

Discussion

The major findings from this study are that dapsone, as a single drug and in combination with doxycycline and doxycycline + rifampin as well as doxycycline + rifampin + azithromycin had the most significant effect in reducing the mass and viability as well the protective mucopolysaccharide layers of B. burgdorferi biofilm. These findings might explain at least in part its clinical efficacy seen in recent DDS CT trials [32–34].

In order to eliminate the most resistant forms of B. burgdorferi, there is a need for safe and effective drugs that are able to eliminate all morphological forms of B. burgdorferi including attached biofilm forms [24, 30]. Our recent clinical studies reported that DDS combination therapy [DDS with rifampin and a tetracycline (doxycycline, minocycline) and/or a macrolide (azithromycin, clarithromycin) and/or cephalosporin (cefuroxime axetil)] improved symptoms of fatigue, muscle/joint pain, neuropathy, disturbed sleep, cognitive complaints, and sweats and/or flushing [32–34].

A recent study [35] evaluated DDS for activity against persisters and found it was not only the most active sulfa drug but exhibited in vitro superiority to other antibiotics including rifampin, azithromycin, and minocycline. Unfortunately, these researchers did not evaluate DDS combinations against attached B. burgdorferi biofilm, the most antibiotic resistant form in vitro [24, 30] and a dominant form in a human autopsy study from a Lyme disease patient [31]. Furthermore, a recent mouse model study [42] showed that the biofilm like microcolony and stationary phase planktonic forms (free cells) caused more severe Lyme arthritis with an earlier onset of inflammation and joint swelling than the log phase spirochetes. Therefore, addressing biofilm forms is vital, and for that reason in this study, we added several assays to evaluate dapsone alone and in combination on B. burgdorferi biofilms. We found that dapsone as a single agent is very effective in reducing the attached biofilm forms, and that dapsone combination therapy (DDS CT) with a tetracycline, rifampin and/or macrolide had a more significant effect on reducing the mass and viability as well the protective mucopolysaccharide layers of highly resistant B. burgdorferi biofilm.

Conclusion

Results from this study verify that dapsone alone and in combination with other antibiotics is effective in reducing the antibiotic resistant biofilm forms of B. burgdorferi and support the in vitro effectiveness of DDS CT. Two prior published retrospective studies using DDS CT also showed clinical efficacy in relieving eight major Lyme symptoms. Considering the worldwide spread of borreliosis and significant numbers of individuals with persistent Lyme symptoms, prospective randomized trials are urgently required to evaluate the clinical efficacy of DDS CT.

Limitations

This study evaluated the antibiotic sensitivity of the B. burgdorferi B31 laboratory strain and needs to be repeated with other Bb sensu lato strains as well to evaluate efficacy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the MSIDS Research Foundation, LivLyme Foundation, Lyme Navigator Foundation, Lyme Warriors, and National Philanthropic Trust for their support of the research reported in this paper. Microscopes and cameras were donated by Lymedisease.org, the Schwartz Research Foundation, and the Global Lyme Alliance.

Abbreviations

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- DDS

Dapsone

- DDS CT

Dapsone combination therapy

- DMMB

Dimethylmethylene blue glycosaminoglycan

- EM

Erythema migrans

- GAG

Glycosaminoglycan

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

Authors' contributions

Dr. Richard Horowitz and Dr. Phyllis Freeman helped design the initial study and contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. Krithika Murali, Gauri Gaur, and Dr. Eva Sapi from the University of New Haven helped design the study, performed the laboratory experiments, and were equally involved in the writing and editing of this manuscript.

Funding

MSIDS Research Foundation, LivLyme Foundation, Lyme Navigator Foundation, Lyme Warriors, and National Philanthropic Trust.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from Dr. Eva Sapi, University of New Haven, on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of Dr Richard Horowitz, and do not represent the views of the Tick-Borne Disease Working Group, HHS or the United States.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cook MJ. Lyme borreliosis: a review of data on transmission time after tick attachment. Int J Gen Med. 2014;8:1–8. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S73791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feder HM, Jr, Abeles M, Bernstein M, Whitaker-Worth D, Grant-Kels JM. Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of erythema migrans and Lyme arthritis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24(6):509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kugeler KJ, Farley GM, Forrester JD, Mead PS. Geographic distribution and expansion of human Lyme disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(8):1455–1457. doi: 10.3201/eid2108.141878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donta ST. Tetracycline therapy for chronic Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25(Suppl 1):S52–56. doi: 10.1086/516171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wormser GP, Nadelman RB, Dattwyler RJ, Dennis DT, Shapiro ED, Steere AC, et al. Practice guidelines for the treatment of Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(Suppl 1):S1–14. doi: 10.1086/314053134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eppes SC, Childs JA. Comparative study of cefuroxime axetil versus amoxicillin in children with early Lyme disease. Pediat. 2002;109(6):1173–1177. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dattwyler RJ, Wormser GP, Rush TJ, Finkel MF, Schoen RT, Grunwaldt E, et al. A comparison of two treatment regimens of ceftriaxone in late Lyme disease. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117(11–12):393–397. doi: 10.1007/s00508-005-0361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Center of Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/humancases.html. Accessed 20 Jun 2020.

- 9.Klempner MS, Hu LT, Evans J, Schmid CH, Johnson GM, Trevino RP, et al. Two controlled trials of antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms and a history of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):85–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preac-Mursic V, Wilske B, Gross B, Weber K, Pfister HW, Baumann A, et al. Survival of B. burgdorferi in antibiotically treated patients with Lyme borreliosis. Infect. 1989;17(6):355–359. doi: 10.1007/BF01645543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liegner KB, Rosenkilde CE, Campbell GL, Quan TJ, Dennis DT. Culture-confirmed treatment failure of cefotaxime and minocycline in a case of Lyme meningoencephalomyelitis in the United States. In Program and abstracts of the Fifth International Conference on Lyme Borreliosis, Arlington, VA., May 30-June 2, 1992; Bethesda, Md.: Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, A11.

- 12.Liegner KB, Shapiro JR, Ramsay D, Halperin AJ, Hogrefe W, Kong L. Recurrent erythema migrans despite extended antibiotic treatment with minocycline in a patient with persisting B. burgdorferi infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(2):312–314. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70043-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steere AC, Angelis SM. Therapy for Lyme arthritis: Strategies for the treatment of antibiotic-refractory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(10):3079–3086. doi: 10.1002/art.22131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klempner MS, Noring R, Rogers RA. Invasion of human skin fibroblasts by the Lyme disease spirochete B burgdorferi. J Infect Dis. 1993;167(5):1074–1081. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang JR, Hardham JM, Barbour AG, Norris SJ. Antigenic variation in Lyme disease borreliae by promiscuous recombination of VMP-like sequence cassettes. Cell. 1997;89(2):275–285. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jutras BL, Lochhead RB, Kloos ZA, Biboy J, Strle K, Booth CJ, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi peptidoglycan is a persistent antigen in patients with Lyme arthritis. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2019;116(27):13498–13507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sapi E, Bastian SL, Mpoy CM, Scott S, Rattelle A, Pabbati N, et al. Characterization of biofilm formation by B burgdorferi in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sapi E, Balasubramanian K, Poruri A, Maghsoudlou JS, Socarras KM, Timmaraju AV, et al. Evidence of in vivo existence of B. burgdorferi biofilm in Borrelial lymphocytomas. Eur J Microbiol Immunol. 2016;6(1):9–24. doi: 10.1556/1886.2015.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brorson Ø, Brorson SH. Transformation of cystic forms of B. burgdorferi to normal, mobile spirochetes. Infect. 1997;25(4):240–246. doi: 10.1007/BF01713153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donta ST. Macrolide therapy of chronic Lyme disease. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9(11):PI136–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murgia R, Cinco M. Induction of cystic forms by different stress conditions in B. burgdorferi. APMIS. 2004;112(1):57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm1120110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacDonald AB. Spirochetal cyst forms in neurodegenerative disorders hiding in plain sight. J Med Hypothesis. 2006;67(4):819–832. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miklossy J, Kasas S, Zurn AD, McCall S, Yu S, McGeer PL. Persisting atypical and cystic forms of B. burgdorferi and local inflammation in Lyme neuroborreliosis. J Neuroinflam. 2008;5(1):40. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sapi E, Kaur N, Anyanwu S, Luecke DF, Datar A, Patel S, et al. Evaluation of in-vitro antibiotic susceptibility of different morphological forms of B. burgdorferi. Infect Drug Resist. 2011;4:97–113. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S19201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng J, Wang T, Shi W, Zhang S, Sullivan D, Auwaerter PG, et al. Identification of novel activity against B. burgdorferi persisters using an FDA approved drug library. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2014;3(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/emi.2014.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng J, Shi W, Zhang S, Zhang Y. Identification of new compounds with high activity against stationary phase B. burgdorferi from the NCI compound collection. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2015;4(1):1–15. doi: 10.1038/emi.2015.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng J, Auwaerter PG, Zhang Y. Drug combinations against B. burgdorferi persisters in vitro: eradication achieved by using daptomycin, cefoperazone and doxycycline. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0117207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vancová M, Rudenko N, Vaněček J, Golovchenko M, Strnad M, Rego RO, et al. Pleomorphism and viability of the Lyme disease pathogen B. burgdorferi exposed to physiological stress conditions: a correlative cryo-fluorescence and cryo-scanning electron microscopy study. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:596. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Kybicova K, Vancova M. Metamorphoses of Lyme disease spirochetes: phenomenon of B. burgdorferi persisters. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12(1):237. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3495-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Theophilus PAS, Victoria MJ, Socarras KM, Filush KR, Gupta K, Luecke DF, et al. Effectiveness of Stevia rebaudiana whole leaf extract against the various morphological forms of B. burgdorferi in vitro. Eur J Microbiol Immunol. 2015;5(4):268–280. doi: 10.1556/1886.2015.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sapi E, Kasliwala RS, Ismail H, Torres JP, Oldakowski M, Markland S, et al. The long-term persistence of Borrelia burgdorferi antigens and DNA in the tissues of a patient with Lyme Disease. Antibiotics. 2019;8(4):183. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8040183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horowitz RI, Freeman PR. The use of dapsone as a novel “persister” drug in the treatment of chronic Lyme disease/post treatment Lyme disease syndrome. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 2016;7(3):345. doi: 10.4172/2155-9554.1000345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horowitz RI, Freeman PR. Precision medicine: The role of the MSIDS model in defining, diagnosing, and treating chronic Lyme disease/post treatment Lyme disease syndrome and other chronic illness: part 2. Healthcare. 2018;6(4):129. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6040129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horowitz RI, Freeman PR. Precision medicine: retrospective chart review and data analysis of 200 patients on dapsone combination therapy for chronic Lyme disease/post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome: part 1. Int J Gen Med. 2019;12:101–119. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S193608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng J, Zhang S, Shi W, Zhang Y. Activity of sulfa drugs and their combinations against stationary phase B. burgdorferi in vitro. Antibiotics (Basel) 2017;6(1):10. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics6010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tote K, Vanden Berghe D, Maes L, Cos P. A new colorimetric microtitre model for the detection of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Lett App Microbiol. 2007;46(2):249–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zuidema J, Hilbers-Modderman ESM, Merkus FWHM. Clinical pharmacokinetics of dapsone. Clin-Pharmacokinet. 1986;11(4):299–315. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198611040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holmes NE, Charles PGP. Safety and efficacy review of doxycycline. Clin Med Ther. 2009;1:CMT.S2035. doi: 10.4137/CMT.S2035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garnham JC, Taylor T, Turner P, Chasseaud LF. Serum concentrations and bioavailability of rifampicin and isoniazid in combination. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1976;3(5):897–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1976.tb00644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imamura Y, Higashiyama Y, Tomono K, Izumikawa K, Yanagihara K, Ohno H, et al. Azithromycin exhibits bactericidal effects on Pseudomonas aeruginosa through interaction with the outer membrane. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(4):1377–1380. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1377-1380.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ginsburg CM, McCracken GH, Jr, Petruska M, Olson K. Pharmacokinetics and bactericidal activity of cefuroxime axetil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28(4):504–507. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.4.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng J, Li T, Yuan Y, Yee R, Bai C, Cai M, et al. Biofilm/persister/stationary phase bacteria cause more severe disease than log phase bacteria – Biofilm B. burgdorferi not only display more tolerance to Lyme antibiotics but also cause more severe pathology in a mouse arthritis model: Implications for understanding persistence, PTLDS and treatment failure. Discov Med. 2019;148:125–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from Dr. Eva Sapi, University of New Haven, on reasonable request.