Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a new infectious disease, and acute respiratory syndrome (ARDS) plays an important role in the process of disease aggravation. The detailed clinical course and risk factors of ARDS have not been well described.

Material/Methods

We retrospectively investigated the demographic, clinical, and laboratory data of adult confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Beijing Ditan Hospital from Jan 20 to Feb 29, 2020 and compared the differences between ARDS cases and non-ARDS cases. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression methods were employed to explore the risk factors associated with ARDS.

Results

Of the 130 adult patients enrolled in this study, the median age was 46.5 (34–62) years and 76 (58.5%) were male. ARDS developed in 26 (20.0%) and 1 (0.8%) death occurred. Fever occurred in 114 patients, with a median highest temperature of 38.5 (38–39)°C and median fever duration of 8 (3–11) days. The median time from illness onset to ARDS was 10 (6–13) days, the median time to chest CT improvement was 17 (14–21) days, and median time to negative nucleic acid test result was 27 (17–33) days. Multivariate regression analysis showed increasing odds of ARDS associated with age older than 65 years (OR=4.75, 95% CL1.26–17.89, P=0.021), lymphocyte counts [0.5–1×109/L (OR=8.80, 95% CL 2.22–34.99, P=0.002); <0.5×109/L(OR=36.23, 95% CL 4.63–2083.48, P=0.001)], and temperature peak ≥39.1°C (OR=5.35, 95% CL 1.38–20.76, P=0.015).

Conclusions

ARDS tended to occur in the second week of the disease course. Potential risk factors for ARDS were older age (>65 years), lymphopenia (≤1.0×109/L), and temperature peak (≥39.1°C). These findings could help clinicians to predict which patients will have a poor prognosis at an early stage.

MeSH Keywords: COVID-19; Fever; Lymphopenia; Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Adult; Risk Factors

Background

At the end of 2019, several cases of viral pneumonia of unknown origin were reported in Wuhan, China [1–5]. High-throughput sequencing identified the causative pathogen was a novel coronavirus, which was named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). On February 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) named the disease caused by this virus Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). So far, COVID-19 has affected more then 140 countries/regions and has become a major global health concern [6].

According to previous literature, there is a wide clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection, including asymptomatic infection, mild respiratory symptoms, severe viral pneumonia with respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and death. Most infected patients present mild symptoms and quickly recover, but some progress rapidly to ARDS and require ICU care. ARDS is associated with 35.3% ICU mortality and 40.0% hospital mortality according to a large epidemiological study in 50 countries [7]. Currently, there are no efficacious antiviral therapies or vaccines for COVID-19. To reduce the mortality and alleviate the shortage of medical resources, it is essential to identify patients at higher risk of ARDS at an early stage. However, information on the detailed clinical course and risk factors for ARDS in COVID-19 patients is limited. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the clinical characteristics, laboratory results, and imaging features between COVID-19 patients with ARDS and those without ARDS, to explore risk factors for ARDS in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Material and Methods

Study design and patients

There were 145 patients who were diagnosed based on Chinese management guidelines for COVID-19 (Trial Version 6, Revised) (meet the criteria for suspected cases and have at least 2 positive results by the RT-PCR assay for SARS-CoV-2 or a genetic sequence that matches SARS-CoV-2 [8,9]) and hospitalized in the hospital from Jan 20 to Feb 29, 2020. After excluding 15 minor patients (age <18 years old), we enrolled 130 adult patients and divided them into an ARDS group and a non-ARDS group.

Laboratory confirmation

Laboratory confirmation of COVID-19 was performed at the Beijing Center for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) and the Infectious Diseases Laboratory of the hospital (audited and authorized by the CDC). Respiratory specimens, including oropharyngeal swab, nasopharyngeal swab, or sputum, were collected from all patients on admission. Viral RNA was extracted within 2 h in a biosafety cabinet in a BSL-2 lab using the QIAamp® Viral RNA Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time RT-PCR assays targeting the open reading frame 1ab (ORF1ab) region and nucleoprotein (N) gene of SARS-CoV-2 were conducted for nucleic acid testing. The reaction system and amplification conditions were according to the manufacturer’s specifications (Shanghai BioGerm Medical Technology Co. LTD, China). A cycle threshold value of both genes less than or equal to 37 was considered as positive for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis. All the procedures were conducted in accordance with the protocol established by the WHO [10].

Data collection

We collected the patients’ information from their electronic medical records that were set up when they were hospitalized in the hospital, including basic demographics [sex, age, body mass index (BMI), and comorbidities], epidemiological history (indicated if patients have resided in or traveled to Wuhan within 14 days before illness onset), clinical characteristics, course of disease (days from illness onset to diagnosis, lopinavir/ritonavir treatment. temperature recovery, chest CT improvement, negative nucleic acid test result), and clinical outcomes. Laboratory findings included whole blood counts [white blood cell (WBC) count, lymphocyte (LYM) count], blood biochemistry [creatinine clearance rate (Ccr), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatinine kinase (CK), creatine kinase isoenzyme (CK-MB), C-reactive protein (CRP)], erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and coagulation function [prothrombin time (PT), fibrinogen (FIB), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), and thrombin time (TT)]. Unilateral or bilateral lung inflammation were also recorded according to chest computed tomography (CT).

Definitions

Secondary bacterial infection was diagnosed if patients showed clinical symptoms of pneumonia and bacteremia with a positive culture of a pathogen from lower respiratory tract specimens (sputum, endotracheal aspirates, or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid) or from blood samples within 2 days after admission [8]. Fever was defined as axiliary temperature of at least 37.3°C. ARDS was diagnosed according to the Berlin Definition as follows: (1) presence of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure with PaO2/FiO2×(760/actual atmosphere) ≤300 mmHg; (2) onset within 1 week of a known clinical insult or new or worsening respiratory symptoms; (3) chest imaging showed bilateral opacities without pleural effusion, atelectasis or nodules; and (4) no cardiac failure or body fluid overload [11,12]. Liver injury, kidney injury, and myocardial injury was diagnosed if serum levels were above the 99th percentile upper reference limit. Coagulation abnormality was defined by the prolongation of PT, APTT, and TT, and increased level of FIB. Nucleic acid conversion was defined as negative nucleic acid in nasopharyngeal swabs or sputum twice with an interval of at least 24 h [8].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) as appropriate. Categorical variables were summarized as the counts and percentages in each category. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were applied to continuous variables, and chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables as appropriate. To explore the risk factors associated with ARDS, univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used. Considering the frequency of outcome variables and the total subject observations, 6 variables were chosen for multivariate analysis based on previous findings. Previous studies showed that elderly patients (age >65 years), chronic illness, and lymphopenia were risk factors for severe illness in COVID-19 patients [1–5,13]. Fever was the most common manifestation of COVID and severe cases tended to have a higher temperature peak and longer fever duration than the non-severe cases [3,4]. Early diagnosis and use of effective antiviral drugs can reduce the mortality of influenza patients [14], predicated on which we consider antiviral therapy (lopinavir/ritonavir) as potential prognostic factor of COVID-19. Although severe cases had more prominent abnormalities, laboratory findings might be difficult to obtain under emergency circumstances. Therefore, we chose age>65 years, lymphopenia, comorbidities (which was statistically different), the highest temperature, duration of fever, and antiviral therapy as potential risk factors of ARDS. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted with SPSS 16.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethnic statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital (2020-009-01). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or from a legal guardian.

Results

In total, 130 adult patients were included in this study; 76 (58.5%) were males, and the median age was 46.5 (34–62) years, ranging from 18 to 92 years. Sixty-four (49.2%) patients were Wuhan imported cases. Thirty-six (27.7%) patients had comorbidities, with hypertension (16.9%) and diabetes (9.2%) being the most common comorbidities. Six (4.6%) patients experienced secondary bacterial infection before ARDS. Eighty-four (64.6%) patients were given lopinavir/ritonavir tablets orally with 500 mg twice a day [8] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, diagnostic time, treatment and comorbidities at baseline in Beijing, China.

| Clinical characteristics | All patients (n=130) | Non-ARDS (n=104) | ARDS (n=26) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||

| Male sex – No. (%) | 76 (58.46) | 44 (56.73) | 17 (65.38) | 0.083 |

| Age, Median (range) – years | 46.5 (34.0–62.0) | 40.0 (33.0–57.8) | 63.50 (45.8–75.0) | 0.000 |

| >65 years No. (%) | 24 (18.46) | 11 (10.58) | 13 (50.00) | 0.000 |

| BMI, Median(range) – kg/m2 | 24.68 (21.68–27.61), n=65 | 24.68 (20.56–26.88), n=50 | 25.39 (22.14–28.39), n=15 | 0.445 |

| >30 kg/m2 – No. (%) | 6 (9.23) | 4 (8.00) | 2 (13.33) | 0.907 |

| Wuhan – No. (%) | 64 (49.23) | 49 (47.12) | 15 (57.69) | 0.335 |

| Comorbidities | 36 (27.69) | 24 (23.08) | 12 (46.15) | 0.019 |

| Hypertension – No. (%) | 22 (16.92) | 13 (12.50) | 9 (30.77) | 0.017 |

| DM2 – No. (%) | 12 (9.23) | 7 (6.73) | 5 (19.23) | 0.112 |

| COPD – No. (%) | 4 (3.08) | 3 (2.88) | 1 (0.84) | 1.000 |

| Hypothyroidism – No. (%) | 5 (3.85) | 5 (4.81) | 0 (0) | 0.569 |

| CHD – No. (%) | 4 (3.08) | 2 (1.92) | 2 (7.69) | 0.374 |

| CVD – No. (%) | 2 (1.54) | 1 (0.96) | 1 (3.85) | 0.859 |

| CRF – No. (%) | 2 (1.54) | 1 (0.96) | 1 (3.85) | 0.859 |

| Bacterial infection on admission – No. (%) | 6 (4.62) | 1 (0.96) | 5 (19.23 | 0.001 |

DM2 – diabetes mellitus type 2; COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHD – chronic heart disease; CVD – chronic vascular disease; CRF – chronic renal failure.

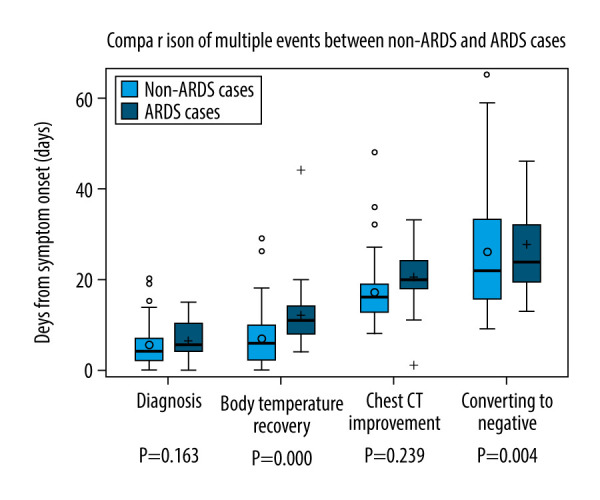

The median time from illness onset to diagnosis was 5 (2–8) days. Fever was detected in 114 (87.7%) patients. The median highest temperature was 38.5 (38–39)°C and fever duration was 8 (3–11) days. The most common respiratory symptoms were cough (63.8%) and sputum (32.3%). Pneumonia on admission was detected in 124 (95.4%) patients. Twenty-six (20.0%) developed ARDS, with a median time of 10 (6–13) days after diagnosis. Eighteen (13.9%) patients had severe ARDS and were transfer to the ICU. Ten patients (7.7%) had gastrointestinal symptoms and 8 (5.5%) had nasal congestion or watery eyes. As of March 20, 122 (93.9%) patients showed chest CT improvement in pneumonia after a median time of 17 (14–21) days. There were 101 (77.7%) patients discharged from the hospital. A continuous negative RT-PCR test result was obtained by 110 (84.6%) patients after a median time of 27 (17–33) days, but 12 (10.7%) patients were re-hospitalized due to positive results and were re-examined for nucleic acid 2 weeks after hospital discharge. Only 1 (0.8%) patient died. All the above results are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics, events of COVID cases in Beijing, China.

| Clinical characteristics | All patients (n=130) | Non-ARDS (n=104) | ARDS (n=26) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | ||||

| Day of diagnosis, Median (range) – Days | 5 (2–8) | 4 (2–7) | 5 (4–10) | 0.163 |

| Day of body temperature recovery, Median (range) – Days | 8 (3–11), n=114 | 6 (2–10), n=88 | 11 (8–14) | 0.000 |

| Day of Nucleic acid negative, Median (range) – Days | 23 (17–33), n=110 | 22 (14–34), n=88 | 24 (19–33), n=22 | 0.239 |

| Day of chest CT improvement, Median (range) – Days | 17 (14–21), n=122 | 16 (13–20), n=97 | 20 (18–25), n=25 | 0.004 |

| Symptom | ||||

| Fever – No. (%) | 114 (87.69) | 88 (84.62) | 26 (100) | 0.072 |

| Temperature peak, Median (range) – °C | 38.5 (38–39) | 38.3 (38.0–38.8) | 39.1 (38.8–39.5) | 0.000 |

| Cough – No. (%) | 83 (63.84) | 61 (58.65) | 22 (84.61) | 0.014 |

| Sputum – No. (%) | 42 (32.31) | 31 (29.81) | 11 (42.31) | 0.223 |

| Digestive tract symptoms – No. (%) | 10 (7.69) | 6 (5.77) | 4 (15.38) | 0.217 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Lopinavir/ritonavir therapy – No. (%) | 84 (64.62) | 74 (71.15) | 10 (38.46) | 0.002 |

Figure 1.

Comparison of multiple events between non-ARDS and ARDS cases.

Lymphopenia was diagnosed in 41.1% (53/130) of patients. Reduced CD4+ cells and CD8+ cells were found in 71.9% (64/81) and 46.1% (41/81) of patients, respectively. Increased CRP was found in 74.4% (96/129) of patients. Coagulation abnormalities were found in 80.6% (104/129), showing prolonged PT, APTT, TT, and increased FIB. High levels of myocardial enzymes were found in 59.7% (77/129) of patients, including LDH, HBDH, CK, and CM-MB. Liver injury was detected in 31.8% (41/129) of patients, and 3.9% (5/129) had renal injury. These results are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Laboratory and radiologic findings of COVID cases in Beijing, China.

| Clinical characteristics | All patients (n=130) | Non-ARDS (n=104) | ARDS (n=26) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Routine blood indexes | ||||

| WBC, Median (range) – 109/L | 4.45 (3.50–5.49) | 4.45 (3.55–5.19) | 4.40 (3.19–6.10) | 0.662 |

| <4×109/L, No. (%) | 51/129 (39.53) | 39/103 (37.86) | 12/26 (46.15) | 0.440 |

| Lym count, Median (range) – 109/L | 1.07 (0.72–1.50) | 1.18 (0.94–1.57) | 0.60 (0.42–0.77) | 0.000 |

| >1.0×109/L, No. (%) | 76/129 (58.91) | 73/103 (70.87) | 3/26 (11.54) | |

| 0.5–1.0×109/L, No. (%) | 41/129 (31.78) | 28/103 (27.18) | 13/26 (50.00) | 0.000 |

| <0.5×109/L, No. (%) | 12/129 (9.30) | 2/103 (0.99) | 10/26 (38.46) | |

| Blood biochemical | ||||

| Ccr, Median (range) – ml/min | 112.2 (82.2–135.2) | 116.6 (84.5–137.2) | 107.1 (71.4–120.1) | 0.092 |

| <90 ml/min, No. (%) | 43/126 (34.1) | 33/102 (32.4) | 10/24 (41.7) | 0.388 |

| Cr, Median (range) – umol/l | 68.5 (55.85–82.10) | 68.00 (55.80–80.70) | 69.55 (55.60–88.45) | 0.557 |

| >104 umol/l, No. (%) | 5/129 (3.88) | 5/103 (4.85) | 0 | 0.564 |

| ALT, Median (range) – u/l | 25.80 (18.45–37.95) | 24.80 (17.20–36.70) | 34.5 (21.48–54.68) | 0.020 |

| >40 u/l, No. (%) | 29/129 (22.48) | 18/103 (17.47) | 10/26 (38.46) | 0.020 |

| LDH, Median (range) – u/l | 227 (189–310) | 218 (188–283) | 305 (195–373) | 0.026 |

| >250 u/l, No. (%) | 49/117 (41.88) | 34/92 (36.96) | 15/25 (60.00) | 0.058 |

| CK, Median (range) – u/l | 66.90 (46.20–105.90) | 66.00 (48.40–103.00) | 71.10 (29.35–190.50) | 0.842 |

| >198 u/l, No. (%) | 12/129 (10.26) | 6/103 (9.09) | 6/26 (11.54) | 0.020 |

| CK-MB, Median (range) – u/l | 16.00 (13.00–21.3) | 15.50 (12.90–18.80) | 15.90 (13.20–22.80) | 0.309 |

| >25 u/l, No. (%) | 9/126 (7.14) | 4/91 (4.40) | 5/25 (20.00) | 0.021 |

| CRP, Median (range) – mg/dl | 23.70 (5.00–53.10) | 15.40 (4.30–34.00) | 102.00 (45.50–120.63) | 0.000 |

| >5 mg/dl, No. (%) | 96/129 (74.42) | 71/103 (68.93%) | 25/26 (96.15%) | 0.004 |

| Coagulation function | ||||

| PT, Median (range) – s | 12.30 (11.70–13.40) | 12.10 (11.60–13. 25) | 13.15 (12.50–13.60) | 0.001 |

| >12.5 s, No. (%) | 57/127 (44.88) | 38/101 (37.62) | 19/26 (73.08) | 0.001 |

| FIB, Median (range) – mg/dl | 343.00 (230.00–405.00) | 327 (221–387) | 415 (305–468) | 0.000 |

| >400 mg/dl, No. (%) | 33/127 (25.98) | 19/101 (18.81) | 14/26 (53.85) | 0.000 |

| Chest CT | ||||

| Lung inflammation No. (%) | 125 (96.15) | 99 (96.12) | 26 (100) | 0.698 |

| Bilateral lung inflammation No. (%) | 71 (54.62) | 45 (43.27) | 26 (100) | 0.000 |

| Others | ||||

| CD4+T lymphocyte count, Median (range) – cells/ul | 537 (384–713.5) | 537 (404–717) | 471 (273–705) | 0.000 |

| <706 cells/ul, No. (%) | 64/89 (71.91) | 49/69 (71.01) | 15/20 (75.00) | 0.727 |

| CD8+T lymphocyte count, Median (range) – cells/ul | 331 (187.5–576) | 409 (257–624) | 170 (127–273) | 0.192 |

| <320 cells/ul, No. (%) | 41/89 (46.07) | 24/69 (34.78) | 17/20 (85.00) | 0.000 |

In univariate analysis, there were statistically significant differences in age, secondary bacterial infection, lopinavir/ritonavir therapy, temperature peak, days from illness onset to body temperature recovery and chest CT improvement, lymphocyte count, HBDH, CRP, PT, FIB, ESR, and CD4+ T lymphocyte count (P<0.01). In the multivariate logistic regression model, we found that older age (>65 years), maximum body temperature ≥39.1°C, and lymphopenia (≤1.0×109/L) were associated with increased risk of developing ARDS (P>0.05). These results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The risk factors of ARDS.

| Clinical characteristics | Univariable OR (95% CI) | p value | Multivariable OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||

| Age, years | ||||

| >65 years (vs. 18–65 years) | 8.46 (3.14–22.77) | 0.000 | 4.75 (1.26–17.89) | 0.021 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension (vs. no hypertension) | 3.71 (2.72–220.82) | 0.010 | – | – |

| Fever | ||||

| Maximum body temperature, °C | 6.83 (2.77–16.82) | 0.000 | 5.35 (1.38–20.76) | 0.015 |

| Day of body temperature recovery, Days | 1.15 (1.05–1.25) | 0.002 | – | – |

| Treatment | ||||

| Lopinavir/ritonavir therapy (NO – lopinavir/ritonavir) | 0.25 (0.10–0.62) | 0.003 | – | – |

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| Lym count, 109/L | ||||

| >1.0 | 1 (ref) | – | – | |

| 0.5–1.0 | 2.71 (1.12–6.56) | 0.024 | 8.80 (2.22–34.99) | 0.002 |

| <0.5 | 31.88 (6.39–159.00) | 0.000 | 36.23 (4.63–283.48) | 0.001 |

WBC – white blood cell; Neu – neutrophil; Lym – lymphocyte; HGB – hemoglobin; PLT – platelet; Bun – blood urea nitrogen; Cr – serum creatinine; ALT – alanine transaminase; AST – glutamate transaminase; LDH – lactate dehydrogenase; HBDH – hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase; CK – creatine kinase; CKMB – myocardial creatine kinase isoenzyme; PT – prothrombin time; APTT – activated partial thromboplastin time; FIB – fibrinogen; TT – thrombin time; CRP – C-reactive protein; LAC – lactic acid; SAA – serum amylase-like protein; ESR – erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Discussion

We identified several risk factors associated with ARDS in COVID-19 patients, including older age (>65 years), maximum body temperature ≥39.1°C, and lymphopenia (≤1.0×109/L). Additionally, elevated levels of myocardial enzymes, decreased CD4+ T lymphocytes, and coagulation abnormality were more common in patients with ARDS.

According to previous studies, older age and underlying diseases (hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease) were related to the severity of COVID-19 patients [2–5,13]. In this study, we also found that older age (>65 years) was associated with increased risk of ARDS in COVID-19 patients. The defects in both cell-mediated and humoral immunity progressively increase with age and can lead to a deficiency in control of viral replication [15]. It is generally agreed that age-related decrease in the adaptive immune response and presence of more underlying diseases place elderly patients at increased risk for infection. There have been reports that older age is an important independent predictor of mortality in patients with SARS, MERS, and influenza [16,17]. A report of 1591 patients who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 and admitted to ICUs showed that hypertension (49%) was the most common comorbidity, followed by cardiovascular disorders (21%), hypercholesterolemia (18%), and diabetes (17%) [18]. However, no statistically significant differences were found in underlying diseases, which may be related to the relatively limited number of elderly patients (18.5%) in our study population compared to previous studies.

Consistent with recent reports, the most common symptom of COVID-19 patients was fever. In univariate analysis, patients with ARDS had longer duration of fever and higher maximum temperature (P<0.001). The median time of fever duration in ARDS cases was almost twice that of non-ARDS cases [11(8–14) vs. 6 (2–10) days]. Patients with higher body temperature peak had higher risk of ARDS, especially for patients with high fever (≥39.1°C), which has rarely been reported in the literature. These symptoms may be helpful in clinical practice for preliminary decision-making. High body temperature may be an extracorporeal indicator of the inflammatory response mainly caused by endogenous pyrogens such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF). Studies have reported that IL-6 levels were clearly elevated in non-survivors compared with survivors throughout the clinical course [13], and some other studies showed that, compared with COVID-19 patients from general wards, patients in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) had increased serum levels of TNF-α and other inflammatory factors [13]. These high levels of cytokines are also an important cause of cytokine storm, which one of the major causes of ARDS and plays an important role in the process of disease aggravation [15,19].

In terms of laboratory tests, the decrease of peripheral blood lymphocytes and T lymphocytes was more significant in ARDS patients (P<0.001). Multiple studies have suggested that lymphopenia is common and more serious in severe patients, which was consistent with our study. Flow cytometry analysis in peripheral blood of COVID-19 patients showed that the reduction in T lymphocytes was mainly caused by lymphocytopenia. Recent pathological anatomy research showed that the number of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in peripheral blood was greatly reduced, and they were over-activated [20], which may lead to T lymphocyte depletion. In addition, in the case of SARS-CoV infection, T lymphocyte apoptosis via TNF-mediated signal pathways has been reported. T lymphocytes are crucial for clearing virus, inhibiting overactive immune responses, and avoiding exacerbation of illness. The decrease of T cells may be an important reason for the aggravation of the disease and may be an indicator of severe COVID-19.

In univariate analysis, elevated levels of myocardial enzymes and coagulation abnormality were also more common in severe patients with ARDS. One of the contributory mechanisms of coagulopathy is that the systemic pro-inflammatory cytokine responses induce procoagulant factors and hemodynamic changes [21]. Cardiac and other organ injury may be partly caused by angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is the key receptor for SARS-CoV-2 cell entry [28] and is abundant in myocytes and vascular endothelial cells [22,23–29]. This indicates that the pulmonary, hepatic, or myocardial injury may be ACE2-related. Nevertheless, pathological analyses of lung, liver, and heart biopsy specimens from COVID-19 patients found no obvious intranuclear or intracytoplasmic viral inclusions, but lung tissue showed viral cytopathic-like changes [20]. Another possible explanation is the severe immune-mediated inflammation, such as cytokine storm, which might also contribute to organ injuries and even lead to serious organ failure in some critically ill patients. More studies are needed to clarify the main mechanism of SARS-CoV-2-related tissue damage.

In the present study, 64.62% of patents were treated with lopinavir/ritonavir, and the proportion in the non-ARDS group was significantly higher than that in ARDS cases in univariate analysis. However, the possibility of antiviral therapy blocking the progression of disease cannot be excluded. Our results may be biased because the assignment of lopinavir/ritonavir treatment was not randomized but mainly depended on the clinician’s judgement based on the patients’ tolerance to medication and safety concerns. Lopinavir/ritonavir is an antiviral drug widely used in the treatment of HIV, and the use of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of coronavirus infection has been reported. Chu et al. analyzed the antiviral effect of lopinavir/ritonavir combined with ribavirin in 41 patients with SARS in Hong Kong, China in 2003 and found that the total mortality rate (2.3% vs. 15.6%) and intubation rate (0% vs. 11.0%) were significantly lower than in patients receiving ribavirin alone [30]. In a non-human primate model, subjects who were treated with LPV/r or interferon-β-1b for MERS-CoV had a better prognosis than those who did not receive treatment [31], but a recent study on the efficacy of COVID-19 treatment reached different conclusions. According to a retrospective analysis (22 lopinavir/ritonavir therapy cases vs. 25 control cases), lopinavir/ritonavir therapy has no effect on improving symptoms or shortening the time to virus nucleic acid turning negative in respiratory samples [24]. In a randomized, controlled, open-label analysis (99 lopinavir/ritonavir therapy cases vs. 100 control cases), lopinavir-ritonavir led to a median time to clinical improvement that was shorter by 1 day than that observed with standard care (hazard ratio, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.91) [25]. Large prospective, randomized, controlled, and double-blinded studies are still needed to further explore the effectiveness of lopinavir/ritonavir.

An important finding of the present study was that 10.7% of patients were re-hospitalized due to positive results, perhaps because of false-negative RT-PCR results when patients were discharged from the hospital. It was recently found that after the pharyngeal swab results became negative, the nucleic acid could still be detected in sputum or feces, indicating that the patients with negative pharyngeal swab results were not truly virus-free [26]. Sputum is more reliable than nasopharyngeal swabs as a test sample for use in guiding isolation. Although no infection was found in people with close contacts with them, it is still unknown whether they continue to pose a risk of infection to others.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study and not all data were complete for all patients, which may have increased the occurrence of selection and measurement biases in the results or underestimated the value of factors in predicting ARDS. Second, the number of ARDS patients was small. Therefore, large-scale, multicenter epidemiological studies with complete data to identify potential predictive risk factors for ARDS in COVID-19 patients are still necessary.

Conclusions

In summary, older age (>65 years), maximum body temperature, and lymphopenia (≤1.0×109/L) were associated with increased risk of ARDS. Most patients aggravated during the second week of the clinical course, when a minority of patients developed ARDS. Pneumonia improved in the third week, and the conversion of nucleic acid results from positive to negative mostly occurred in the fourth week.

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors of the primary studies for their timely and helpful responses to our information requests.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92:401–2. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. Med Rxiv. 2020 20020974. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus (2019-n Co V) situation report-59. Published March 20, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200319-sitrep-59-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=c3dcdef9_2.

- 7.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315:788–800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Diagnosis and treatment protocols for patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia (Trial Version 6, Revised) http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202003/46c9294a7dfe4cef80dc7f5912eb1989.shtml.

- 9.World Health Organization. Clinical management of COVID-19. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/clinical-management-of-covid-19. [PubMed]

- 10.World Health Organization. Laboratory diagnostics for novel coronavirus 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-331501.

- 11.Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riviello ED, Kiviri W, Twagirumugabe T, et al. Hospital incidence and outcomes of the acute respiratory distress syndrome using the Kigali Modification of the Berlin Definition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:52–59. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201503-0584OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uyeki TM, Bernstein HH, Bradley JS, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2018 update on diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management of seasonal influenzaa. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e1–47. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chousterman BG, Swirski FK, Weber GF. Cytokine storm and sepsis disease pathogenesis. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39:517–28. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi KW, Chau TN, Tsang O, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in 267 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:715–23. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong KH, Choi JP, Hong SH, et al. Predictors of mortality in Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) Thorax. 2018;73:286–89. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Godel P, Subklewe M, et al. Cytokine release syndrome. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:56. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0343-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–22. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson JA, Warren-Gash C. Cardiovascular complications of acute respiratory infections: Current research and future directions. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019;17:939–42. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2019.1689817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. Regulation of ACE2 in cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H2373–79. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00426.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendoza-Torres E, Oyarzun A, Mondaca-Ruff D, et al. ACE2 and vasoactive peptides: Novel players in cardiovascular/renal remodeling and hypertension. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;9:217–37. doi: 10.1177/1753944715597623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J, Ling Y. [Efficacies of lopinavir/ritonavir and abidol in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia]. Zhonghuachuanranbingzazhi. 2020;38:86–89. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu F, Yan L, Wang N, et al. Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):793–98. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Channappanavar R, Fehr AR, Vijay R, et al. Dysregulated Type I interferon and inflammatory monocyte-macrophage responses cause lethal pneumonia in SARS-CoV-infected mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(2):181–93. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–80.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, et al. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203(2):631–37. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu CM, Cheng VC, Hung IF, et al. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: Initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax. 2004;59:252–56. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan JF-W, Yao Y, Yeung M-L, et al. Treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir or interferon-β1b improves outcome of MERS-CoV infection in a nonhuman primate model of common marmoset. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1904–13. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]