Abstract

Background

Understanding the natural history of non-malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (PNSTs) in neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is critical to optimal clinical care and the development of meaningful clinical trials.

Methods

We longitudinally analyzed growth of plexiform neurofibromas (PNs) and of PNSTs with distinct nodular appearance (distinct nodular lesions [DNLs]) using volumetric MRI analysis in patients enrolled on a natural history study (NCT00924196).

Results

DNLs were observed in 58/122 (45.6%) patients (median 2 DNLs/patient). In DNLs that developed during follow-up, median age of development was 17 years. A moderate negative correlation was observed between the estimated PN growth rate and patients’ age at initial MRI (Spearman’s r [95% CI]: −0.60 [−0.73, −0.43], n = 70), whereas only a weak correlation was observed for DNLs (Spearman’s r [95% CI]: −0.25 [−0.47, 0.004]; n = 61). We observed a moderate negative correlation between tumor growth rate and baseline tumor volume for PNs and DNLs (Spearman’s r [95% CI]: −0.52 [−0.67, −0.32] and −0.61 [−0.75, −0.42], respectively). Spontaneous tumor volume reduction was observed in 10 PNs and 7 DNLs (median decrease per year, 3.6% and 7.3%, respectively).

Conclusion

We corroborate previously described findings that most rapidly growing PNs are observed in young children. DNLs tend to develop later in life and their growth is minimally age related. Distinct growth characteristics of PNs and DNLs suggest that these lesions have a different biology and may require different clinical management and clinical trial design. In a subset of PNs and DNLs, slow spontaneous regression in tumor volume was seen.

Keywords: atypical neurofibroma, neurofibromatosis, plexiform neurofibroma, volumetric MRI

Key Points.

Distinct nodular lesions (DNLs) have different growth dynamics than plexiform neurofibromas (PNs).

Some PNs and DNLs may show slow spontaneous volume decrease.

Importance of the Study.

Understanding the growth dynamics of non-malignant PNSTs in NF1 is crucial for optimal patient management and design of meaningful clinical trials. We used volumetric MRI analysis to evaluate the longitudinal growth patterns of both PNs and DNLs (PNSTs with distinct nodular appearance, some of which are atypical neurofibromas). While PNs exhibited the largest growth in young children, DNLs were first documented after early childhood and showed growth characteristics independent of age, suggesting they are biologically different. We also demonstrated that slow spontaneous tumor volume reduction may occur in PNs and DNLs, typically starting in adolescence or young adulthood. This natural history data provide an important historical control against which to compare responses and times for progression seen on treatment trials. Overall, our results suggest that tumor type (PN vs DNL), patient age, and tumor volume are associated with PNST growth.

Plexiform neurofibromas (PNs) are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors (PNSTs) seen in approximately 50% of individuals with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).1,2 Most PNs are thought to be congenital or to occur very early in life and are characterized by slow growth, complex shape, and sometimes very large size (over 20% of body weight). These tumors can cause severe morbidity, including pain, neurological dysfunction, and disfigurement as well as having the potential to transform to malignant (M)PNSTs,1–6 with a 15.8% cumulative lifetime risk of MPNST in NF1 patients.7 Most MPNSTs in NF1 patients develop within preexisting PNs,8 and patients with higher PN tumor burden may have increased risk for malignant transformation.5,9,10 Curative complete surgical resections of PNs are rarely feasible without severe morbidity because PNs arise within nerves and complete resection requires sacrificing the nerve and regional tissue infiltrated.11,12 As a result, medical therapies targeting PNs have been evaluated in clinical trials.13

Volumetric MRI analysis is the method of choice to sensitively and reproducibly measure changes in PN size.14 Although growth of PNs was previously thought to be erratic, systematic assessment of tumor volume over time revealed that PN growth is constant within patients for significant periods of time. The most rapid PN growth has been observed in younger patients, but the relationship of tumor growth to other patient or lesion characteristics is less clear.3,15,16

In patients who underwent 18F-flurodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scans for focally increasing PNST concerning for malignant transformation, we previously demonstrated that FDG avidity was localized to distinct nodular–appearing lesions. On histology, some of these lesions had atypical features, suggesting that these lesions may have a different biology than PNs.17 An analysis of 76 pathologically confirmed atypical neurofibromas also showed that many of these tumors have a distinct nodular appearance on MRI.18 A detailed understanding of the natural history of non-malignant PNSTs is required to optimally guide clinical care and clinical trial design.

Our study’s objectives were to comprehensively and longitudinally evaluate growth patterns of PNs and DNLs using volumetric MRI analysis in children and young adults3,19 and to evaluate associations of tumor growth rates with patient and tumor characteristics.

Methods

Patient Selection

Participants in the institutional review board–approved National Cancer Institute (NCI) NF1 natural history study (NCT00924196) enrolled between February 2008 and December 2013 were included in this retrospective analysis. The analysis included data collected up to November 2015, with additional imaging and clinical data collected prior to study enrollment, when available. Patients had clinically confirmed NF120 or a known NF1 mutation and were ≤35 years of age at time of enrollment. Due to NCI’s referral base, the study population is more representative of patients who seek treatment on clinical trials for PNs than the general NF1 population, with many having heavy PN burden. Patients on study were allowed to undergo clinically indicated surgeries and medical treatments and concurrently enroll on treatment trials for PNs. Longitudinal evaluations included detailed clinical exams including height and weight, regional MRIs of PNSTs and whole-body MRIs. MRIs of PNSTs were performed every 3–6 months when patients were enrolled in treatment studies and every 1–3 years when enrolled in the NF1 natural history study alone. In patients with localized PNs, whole-body MRI was performed every 3 years.

Analysis of Clinical Data

Clinical data were collected from protocol case report forms and clinical charts. Demographic information including date of birth, sex, and race was extracted. Dates when patients received medical therapy directed at PNSTs or other NF1 tumors and dates of PNST-related surgeries were noted. At each evaluation for which tumor volume was measured, patients’ height and weight from their NCI visit or any available outside records were collected.

Analysis of MRI Studies

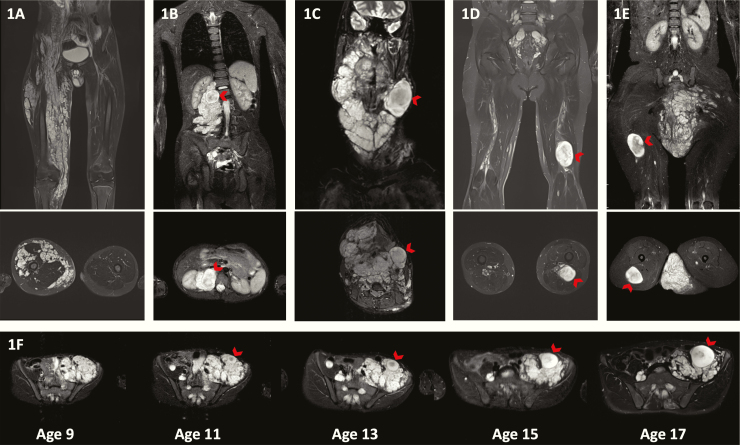

PN was operationally defined as a network-like growth of neurofibromas involving multiple fascicles or branches of a nerve,1 and was diagnosed clinically and based on characteristic imaging features appearing as signal-intense masses on short tau inversion recovery (STIR) MRI sequences3 (Fig. 1A). In addition to PNs, we identified, counted, and measured DNLs (Fig. 1B–E). DNLs were defined as well-demarcated, encapsulated-appearing, ≥3 cm lesions, lacking the central dot sign characteristic of PNs, and present within or outside of a PN. The dates were identified when a nodular-appearing lesion could be first distinguished from the PN and when the nodular lesion reached the size of 3 cm, meeting criteria for DNL.

Fig. 1.

(A) Coronal and axial MRIs of a PN without any DNLs. (B) DNL present within a PN, (C) adjacent to a PN, (D) associated with a major nerve, or (E) outside of a PN. The arrow points to the DNL. (F) Axial MR images showing development of a DNL over time. On the MRI performed at 9 years of age, the tumor appears like a PN with no DNL identifiable even in retrospect. At 11 years, one nodule appears to stand out from the background but does not reach the 3 cm size to classify as a DNL. However, the DNL was evident by age 13 and had grown out of proportion to the plexiform on the MRIs performed at ages 15 and 17.

For volumetric analysis, a measurable PN or DNL was defined as ≥3 cm in longest diameter and visible on at least 3 contiguous MRI slices with clearly identifiable contours. PN and DNL locations were classified using whole-body MRI as head and neck, trunk, extremity, and whole body. Whole-body tumors symmetrically involved most of the large nerves of the body without a regional bulky PN. Tumors were also classified as either superficial, deep, or a combination of the two based on their relationship to the muscle fascia as noted on MRIs.21 For patients with more than one PNST (>1 PN, DNL, or a combination of both), multiple tumor locations were identified, and volumes were measured separately.

Tumor Volume and Growth Rate Measurement

Tumor volumes were calculated for patients with ≥1 measurable lesion with ≥1-year follow-up that included ≥2 MRIs. A semi-automated segmentation method, based on the MEDx software, or manual lesion contouring was used to measure PNST volumes on axial or coronal STIR MRIs.19 During the entire follow-up period some patients underwent PNST-directed medical or surgical interventions. Data collection was truncated at the time of major debulking surgeries, malignant transformation in the tumors, or enrollment on the phase I/II trial of MEK inhibitor selumetinib (NCT01362803), because of reported frequent tumor responses on that study.22 No patients received any other MEK inhibitor therapy during or prior to the data cutoff. To minimize the possibility of treatment effect, the first treatment-free period was separately analyzed for the subset of patients whose follow-up included at least one interval of ≥1 year follow-up with ≥3 MRIs during which they didn’t receive PNST-directed therapies (Fig. 2A, B). If the “treatment-free” portion of follow-up occurred after the patient had received any tumor-directed therapies, a minimum 3-month washout period was used. Serial volume measurements during this treatment-free period were used to evaluate growth patterns, and linear regression was used to estimate growth rate. We separately analyzed a subset of these tumors where patients had not received any tumor-directed medical therapies prior to the “treatment-free” period used for growth rate estimation. Five PNSTs with nonlinear growth where linear regression would not be appropriate for estimating growth rate were excluded from growth rate analyses, and their growth plots and additional details are provided in Supplementary Figure 1.

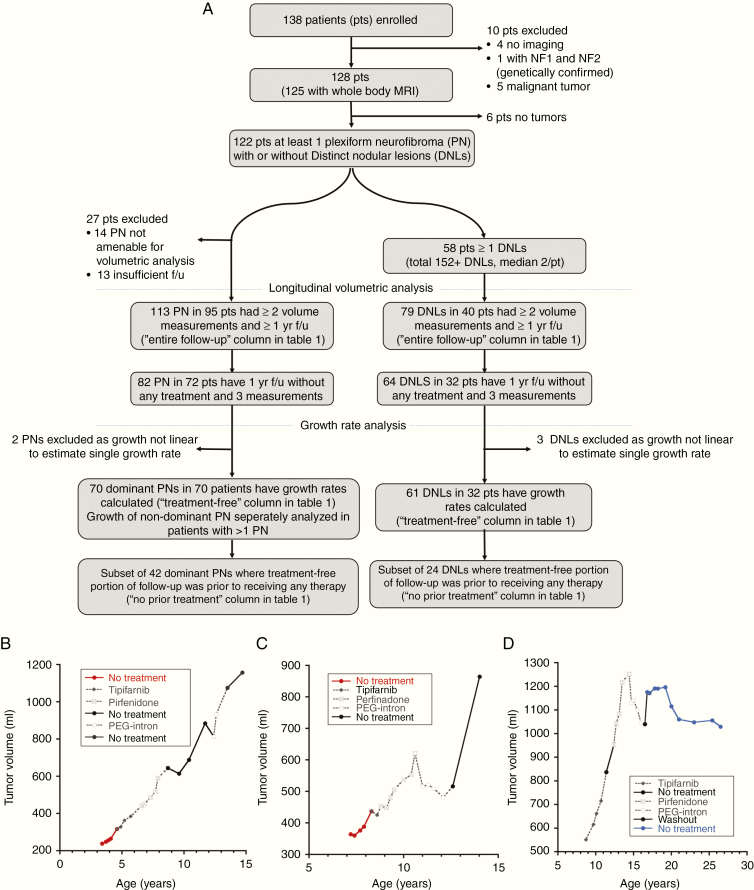

Fig. 2.

(A) Flow diagram describing the patient cohort included in the analysis. (B–D) Examples of growth plots of different tumors during the entire period of follow-up (f/u). Periods during which patients received any medical treatment are shown in gray dotted lines and periods where no treatment was received are shown in continuous lines. The first “treatment-free” portion of follow-up for which growth rate was calculated is highlighted in color. (B) An example of a growth plot where the treatment-free portion was representative of the entire period of follow-up as the treatments did not appear to affect tumor growth. (C) An example of a growth plot where the treatments appear to transiently affect tumor growth. However, after coming off treatment, the tumor growth resumed such that the treatment-free growth rate estimates the overall growth. In these examples, the first “treatment-free” portion of follow-up is shown in red and patients had not received any prior tumor-targeting medical therapies (no-prior-treatment subgroup). (D) An example of a plot where the treatment-free portion of follow-up captured only the period where the tumor growth appears to have stabilized and does not include the initial growth period. Here the first treatment-free portion of follow-up is shown in blue and this was after patient had come off medical therapies targeting PNs.

Spontaneous Tumor Volume Reduction

PNSTs with a final volume lower than the maximum volume during the entire period of observation were noted. Spontaneous PNST volume decrease was defined as final volume ≥10% lower than the maximum volume, with decrease documented on at least 2 successive MRI scans in patients not undergoing PN-directed medical therapy during this time period.

Statistical and Data Analysis

As growth of multiple PNs within a patient could be correlated, for statistical analysis, one dominant PN per patient was included. For patients with multiple tumors, growth rates for different tumors within a patient were compared if volumetric data for the tumors were available over the same time period. The dominant PN was selected based on the tumor with longitudinal volumetric data that was most clinically relevant. When there were ≥1 DNLs, in the absence of a clear way to identify a dominant one, all DNLs were included in the analysis with a goal to better understand their natural history, and were assumed as independent for statistical analysis. Tumor growth and body growth rates were expressed as the percentage of change in tumor volume and patient weight and height per year relative to baseline measurements.

The relationship between estimated tumor growth rates (as calculated by the slope estimates from linear regression) for PNs and DNLs and patients’ age, tumor volume, and patient weight and height at baseline was assessed with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (strong association: |r| > 0.7, moderate association: 0.5 < |r| < 0.7, moderate to weak association: 0.3 < |r| < 0.5, weak association: |r| < 0.3). For categorical variables, tumor growth rate distributions were compared according to sex (male, female), race (white, nonwhite), and age dichotomized at 8.3, 15, and 18 years using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, and the effect size was estimated using the Hodges–Lehmann median difference. The association to tumor location was analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Growth rate distributions were also compared according to lesion type (PN vs DNL) using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. All effect sizes are reported along with 95% confidence interval (CI). For descriptive statistics, unless otherwise indicated, the median is used to estimate central tendency, and 10th and 90th percentile values are provided in parentheses or brackets. Additional details provided in Supplementary Appendix 1–2.

Results

Between February 2008 and December 2013, one hundred thirty-eight patients were enrolled. MRIs were analyzed for 122 patients (74 male/48 female) who had ≥1 PN (Fig. 2). Median age at initial MRI was 9.4 years (3.1, 20.0; n = 122).

Identification and Characterization of DNLs

DNLs were identified in 58/122 (45.6%) patients, with a median of 2 DNLs/patient (1, 5). Thirty-one of 58 patients had >1 DNL. A total of 122 DNLs were present in 55 patients, and 3 patients had >10 DNLs. In these 3 patients, location and age at development were characterized for 10 DNLs. DNLs were present either within a PN (n = 109), adjacent to a PN (n = 6), associated with a major nerve (n = 19), or outside a PN (n = 18) (Fig. 1B–E). Sixty-nine of 152 DNLs were present on the initial available MRI (median age at initial MRI, 15.0 y [3.7, 30.5]). The remaining 83 DNLs were noted to have developed on one of the follow-up MRIs (median age at development, 17.0 y [10.0, 23.9]). Review of prior MRIs in these cases could identify development of the DNL over time (Fig. 1F). The earliest DNL was identified at 1.4 years.

Longitudinal Volumetric Analysis and Growth Rate Assessment

Longitudinal volumetric analysis was performed for 1067 MRIs. At least 2 evaluable MRIs were available for 113 PNs in 95 patients, and tumor growth rate was calculated for 70 dominant PNs in 70 patients who had not received PN-directed therapy during this time (Fig. 2A). Eight patients had 1 additional PN, and one patient had 2 additional PNs for which growth rate was calculated (total 80 PNs in 70 patients). At least 2 evaluable MRIs were available for 79 DNLs in 40 patients and growth rates were calculated for 61 DNLs in 32 patients (Fig. 2A). Initial and final tumor volumes, age at initial MRI, duration of follow-up, and growth rates are summarized in Table 1, and Supplementary Figure 2 shows the proportion of tumors with different growth rates. Plots of tumor volume versus time for the 2 PNs and 3 DNLs that were excluded from growth rate calculation due to nonlinearity are shown in Supplementary Figure 1 along with other examples where linear fit was preferred or only linear growth was evident.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics for PNs and DNLs#

| Plexiform Neurofibroma | Distinct Nodular Lesion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (min, max) 10th, 90th Percentile | Entire Follow-Up N = 113 | Treatment-Free Follow-Up N = 70 | No Prior Treatment# N = 42 | Entire Follow-Up N = 79 | Treatment-Free Follow-Up N = 61 | No Prior Treatment# N = 24 |

| Age at initial MRI, y | 8.4 (0.7, 40.2) 3.2, 18.7 | 10.3 (0.7, 40.2) 3.4, 20.5 | 8.2 (0.7, 40.2) 1.8, 20.2 | 15.2 (2.2, 45.3) 7.2, 25.7 | 18.1 (3.7, 40.2) 8.7, 25.7 | 18.9 (3.7, 40.2) 5.2, 30.5 |

| Initial tumor volume, mL | 295 (4, 4895) 29, 1837 | 374 (4, 4895) 27, 1862 | 273 (4, 4895) 13, 1808 | 13 (2, 122) 5, 66 | 17 (2, 201) 6, 79 | 20 (2, 122) 5, 80 |

| Final tumor volume, mL | 606 (14, 6980) 47, 2990 | 563 (14, 6513) 41, 2210 | 388 (14, 6513) 36, 1970 | 37 (9, 345) 12, 129 | 37 (9, 345) 13, 130 | 35 (11, 172) 15, 139 |

| Duration of follow-up, y | 5.6 (1.0, 14.3) 2.2, 11.1 | 3.0 (1.0, 12.9) 1.2, 7.7 | 2.7 (1.0, 12.4) 1.2, 7.7 | 4.2 (1.0, 12.9) 2.1, 7.7 | 3.7 (1.0, 12.9) 1.5, 6.3 | 3.3 (1.1, 8.0) 1.4, 5.5 |

| # MRI/tumor | 10 (2, 35) 4, 18 | 5 (3, 14) 3, 8 | 5 (3, 14) 3, 8 | 5 (2, 17) 3, 10 | 4 (3, 12) 3, 7 | 4 (3, 9) 3, 6 |

| Growth rate (%/, y)* | NA | 12.4 (−8.5, 246.7) −1.7, 47.9 | 16.6 (−5.3, 246.7) 0.6, 101.7 | NA | 27.1 (−11.9, 290.8) 2.7, 97.5 | 28.1 (1.1, 117.2) 4.8, 88.8 |

| Tumor volume % change final-initial volume per year (%/y) (%/,y)** | 13.9 (−5.8, 252.0) 0.5, 51.3 | 31.5 (−2.2, 343.5) 2.9, 121.3 | ||||

#During the entire period of follow-up, the first treatment-free portion of follow-up during which growth rate was estimated, and the subset where first treatment-free period was before patient received any therapies. No prior treatment group includes a subset of the “treatment-free” group where the patients had not received any tumor-directed medical therapies prior to the “treatment-free” portion of follow-up for which growth rate was calculated.

*Slope estimates from linear regression were used to estimate growth rate during the treatment-free portion of follow-up.

**Tumor volume % change final-initial volume per year (%/y) = 100 x (Final tumor volume − initial tumor volume)/initial tumor volume divided by the duration of follow-up in years during the entire period of follow-up.

In the 70 dominant PNs and 61 DNLs where growth rate was estimated, the age at initial MRI was greater for DNLs compared with PNs (medians, 18.1 y and 10.3 y, respectively; Hodges–Lehmann estimate of the difference between the distributions, 5.84 y [95% CI: 3.45, 8.33]). DNLs generally had higher growth rates with greater variability than dominant PNs (median growth rate, 27.1%/y and 12.4%/y, respectively; Hodges–Lehmann median difference between the tumor types, 14.1 [95% CI: 5.55, 25.2]) (Table 1).

Analysis of Tumor Growth Rate Relationship to Patient Characteristics (Age, Weight, Height, Sex, and Race)

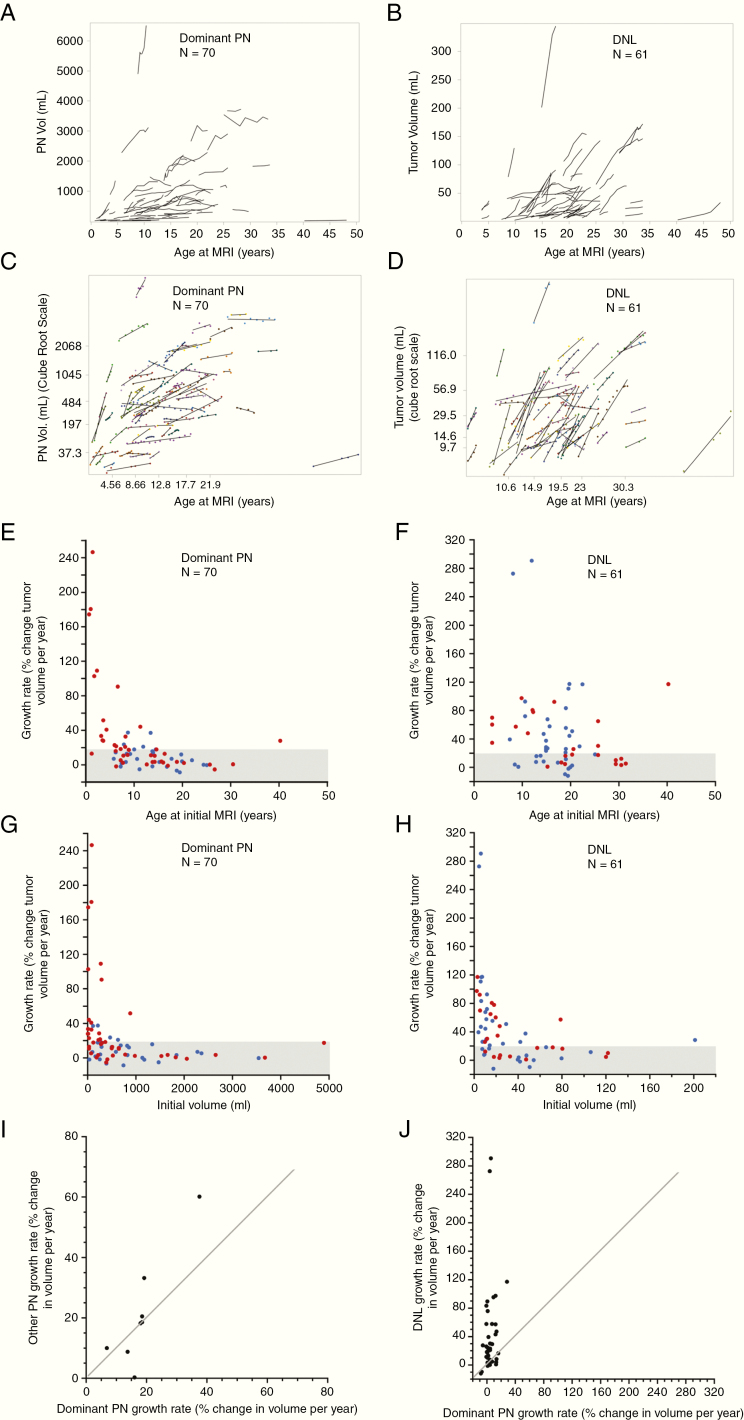

Tumor volume change relative to patients’ age at the initial MRI of the dominant PNs and DNLs is shown in Fig. 3A–D. A moderate negative correlation was observed between estimated growth rate for PNs and patients’ age at initial MRI (Spearman’s r [95% CI]: –0.60 [–0.73, –0.43]) such that the fastest growing tumors were seen in patients <5 years of age, and progressive tumors, defined as growth rate ≥20% per year, were unusual after adolescence (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Figure 3). This relationship of PN growth rate to patient’s age was also seen when age was dichotomized at 8.3, 15, or 18 years, with younger patients having higher median growth rate (Supplementary Table 1). Only a weak negative correlation was found for DNLs (Spearman’s r [95% CI]: –0.25 [–0.47, 0.004]), with many progressive tumors noted even in older patients (Fig. 3F). For patients of age <18 years and ≥18 years, the proportion of DNLs with growth rate ≥20%/year exceeded that for PNs. Similar results were noted when age was dichotomized at 15 years (Supplementary Table 2). Growth rate ≥20%/year was observed in 1/13 PNs and 14/31 DNLs in the ≥18 years age group. The only patient older than 18 years who had a progressive PN had a small paraspinal PN. Similar to the relationship of tumor growth rate to patient’s baseline age, a moderate negative correlation was observed between estimated growth rate for PNs and patients’ weight and height at baseline (Spearman’s r [95% CI]: –0.62 [–0.77, –0.43] and –0.54 [–0.71, –0.32], respectively) and only weak negative correlations were found for DNLs (Spearman’s r [95% CI]: –0.10 [–0.37, 0.19] and –0.05 [–0.33, 0.23], respectively).

Fig. 3.

Tumor volume plotted against patient’s age for the dominant PNs (A) and DNLs (B). Each tumor is shown as a series of line segments. (C, D) Tumor volume plotted against patient’s age for the dominant PNs (C) and DNLs (D), but here the PNST volume is transformed (cube root), quartiles and 10th/90th percentiles are indicated on both axes, and linear regression lines are plotted along with the data (dots). (E, F) Association between estimated tumor growth rate to patient’s age at initial MRI for dominant PNs (E) and DNLs (F). A moderate negative correlation was observed for PNs, whereas only a weak Fig. 3 Continued. association was noted for DNLs. (G, H) Association between estimated tumor growth rate to initial tumor volume for dominant PNs (3G) and DNLs (H). A moderate negative correlation was observed for PNs and DNLs. (E–H) The 42 dominant PNs and 24 DNLs which had not received any tumor-directed medical therapies prior to the “treatment-free” portion of follow-up for which growth rates were calculated (no prior treatment subset) are shown in red, and the remaining PNs and DNLs are shown in blue. (I) Growth rates of the non-dominant PN relative to the growth rate of the dominant PN in the 7 patients (8 non-dominant PNs) who had multiple PNs where tumor volumes were measured over the same follow-up period. No pattern could be noted in our small number of patients. (J) Growth rates of the DNLs relative to the growth rate of the patients’ dominant PN in 26 patients (42 DNLs) where volumes were measured over the same follow-up period. The diagonal lines on I and J indicate the points where the growth rates are equal.

Serial body weight measures were available for the interval of tumor growth rate assessment in 51/70 PNs and 48/61 DNLs. Serial height measures were available for 53/70 PNs and 48/61 DNLs. In 36/51 (71%) PNs and 41/48 (85%) DNLs, tumor growth rate exceeded the growth rate in weight (difference between tumor growth rate and rate of change of weight > 0). In 40/53 (76%) PNs and 44/48 (92%) DNLs, tumor growth rate exceeded the growth rate in height (Supplementary Figure 4).

PN and DNL growth rates were only weakly associated to patients’ sex (Hodges–Lehmann median difference [95% CI] between male and female: 2.34 [–4.77, 11.13] and –5.39 [–21.02, 14.20], respectively) or race (Hodges–Lehmann median difference [95% CI] between white and other races: 1.21 [–5.94, 11.32] and 11.44 [–5.32, 31.66], respectively).

Analysis of Tumor Growth Rate Relationship to Tumor Characteristics (Initial Tumor Volume and Tumor Location)

A moderate negative correlation was observed between calculated growth rate (% change in volume/y) and initial tumor volume for PNs (Spearman’s r –0.52; 95% CI: –0.67, –0.32) and DNLs (Spearman’s r –0.61; 95% CI: –0.75, –0.42) such that larger tumors were associated with slower growth rate despite having a greater absolute change in volume (in mL) per year (Fig. 3G–H).

PNs were located in head and neck (n = 13), trunk (n = 44), extremity (n = 7), or whole body (n = 6). PNs were also classified as superficial (n = 6), deep (n = 40), or combination of superficial and deep (n = 24). DNLs were located in head and neck (n = 7), trunk (n = 34), or extremity (n = 20). One DNL was superficial and the remaining were deep. Overall, there were no significant differences in estimated tumor growth rates and tumor location for either PN or DNL (Kruskal–Wallis test P-values 0.087 and 0.38, respectively). However, the dominant PNs located on extremities tended to have more rapid growth rate compared with whole-body tumors (Hodges–Lehmann estimate of the difference [95% CI]: 17.9 [32.1, 8.97]).

Comparison of Multiple Tumors Within Patients

Eight patients had 2 PNs, for whom an overlapping follow-up period was available in 6. One patient had 3 PNs whose growth rates were measured over the same time period. There were no consistent patterns between growth rates in different PNs within the same patient in this small patient cohort (Fig. 3I, Supplementary Table 3).

For 42/61 DNLs in 26 patients, corresponding PN growth rate for the same period of follow-up was available. In 34/42 (81%) tumor pairs, the DNL growth rate exceeded that of the dominant PN (difference in growth rate > 0) (Fig. 3J, Supplementary Table 4).

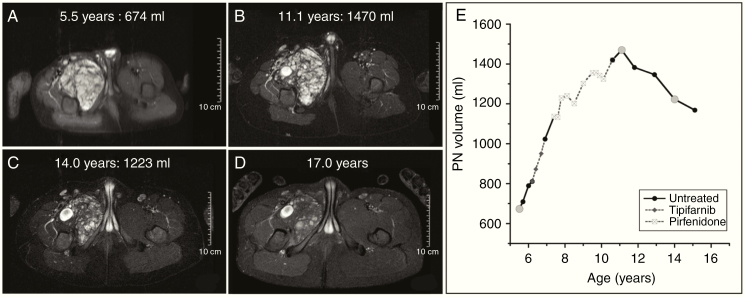

Frequency of Spontaneous Tumor Volume Decrease

In 47/113 PNs the final volume was less than the maximal volume during the entire period of follow-up. In 10/47 PNs, spontaneous gradual tumor volume decrease could be confirmed (median decrease from maximum volume, 19.0%; median decrease per year, 3.6%). In one additional patient, volume decrease (10.7% over 1.3 y) was noted on a single MRI without subsequent imaging for confirmation. In the remaining 36 PNs, spontaneous tumor volume decrease could not be confirmed either because the final volume was <10% from maximum tumor volume, and therefore potentially within measurement error (N = 22), or because the decrease could be potentially attributed to treatment effect (N = 4), or both (N = 10). For DNLs, final volume was lower than maximal observed volume in 12/81 tumors. Spontaneous tumor volume decrease could be confirmed in 7/12 DNLs (median decrease from maximum volume, 16.1%; median decrease per year, 7.3%). In the remaining 5 DNLs, tumor volume decrease was either within 10% of maximum volume (N = 2), or could be potentially attributed to treatment effect (N = 1), or both (N = 2). Tumor volume reduction, rate of reduction, and age at maximal tumor volume are summarized in Table 2. Sequential MR images of a PN demonstrating spontaneous volume decrease and associated changes in MRI signal characteristics are shown in Fig. 4.

Table 2.

Tumor volume and rate of change in 10 PNs and 7 DNLs with confirmed tumor volume regression

| Patient Number (PNST@ Number) | Initial Tumor Volume (Ml) | Maximum Tumor Volume* (Ml) | Final Tumor Volume (Ml) | Age at Maximum Volume, y | Duration of Follow-Up After Maximum Volume,* y | Percent Decrease from Maximum Volume* | Percent Decrease from Maximum Volume/Year# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plexiform neurofibroma | |||||||

| 24 (1) | 818 | 742 | 492 | 19.5 | 3.9 | 33.7 | 8.5 |

| 85 (1) | 118 | 177 | 139 | 18.8 | 2.7 | 21.2 | 7.6 |

| 66 (1)** | 384 | 384 | 317 | 26.7 | 3.0 | 17.4 | 5.3 |

| 7 (1) | 674 | 1470 | 1169 | 11.1 | 4.0 | 20.5 | 5.1 |

| 5 (1) | 3615 | 4426 | 3494 | 30.6 | 4.9 | 21.1 | 4.0 |

| 36 (1) | 2055 | 1879 | 1677 | 19.6 | 3.4 | 10.8 | 3.1 |

| 17 (1) | 551 | 1196 | 1048 | 19.2 | 3.8 | 12.4 | 3.0 |

| 10 (1) | 644 | 871 | 722 | 18.2 | 6.8 | 17.1 | 2.8 |

| 26 (1)** | 408 | 469 | 369 | 8.4 | 10.3 | 21.3 | 2.2 |

| 6 (1)** | 712 | 975 | 848 | 10.1 | 6.5 | 13.0 | 2.1 |

| Distinct nodular lesion | |||||||

| 61 (3)** | 56 | 89 | 60 | 28.3 | 2.0 | 33.0 | 12.9 |

| 24 (2) | 2 | 18 | 9 | 19.5 | 3.9 | 47.4 | 11.9 |

| 85 (2) | 34 | 50 | 37 | 18.8 | 2.7 | 27.4 | 9.6 |

| 61 (6)** | 46 | 52 | 62 | 27.7 | 2.4 | 16.1 | 7.3 |

| 22 (2) | 41 | 67 | 58 | 18.1 | 3.2 | 12.6 | 3.8 |

| 22 (3) | 33 | 47 | 42 | 16.6 | 4.7 | 10.4 | 3.0 |

| 32 (2) | 43 | 43 | 36 | 19.8 | 6.0 | 15.7 | 1.5 |

@PNST = peripheral nerve sheath tumor.

* Maximum volume selected during the period of tumor volume decrease when patient was not receiving any treatment (which in patient 24 PN1 and Patient 36 PN1 was lower than the initial volume).

# Slope estimates from linear regression were used to calculate percent decrease from maximum volume/year.

**Patients did not receive any prior tumor-directed medical therapies prior to period of tumor volume decrease. In all other cases, patients received prior medical therapies, however, the period of decreasing volume included here only reflects the period when patient was not receiving any tumor-directed medical therapies.

Fig. 4.

(A–D) Serial MR images for patient whose tumor increased in size from 674 mL (A) to maximum of 1470 mL (B) and subsequently decreased in size spontaneously (C–D). (E) Tumor volume vs age plot for this PN. Gray circles correspond to the time points for which MR images are presented here. The tumor volume increase occurred both when the patient was not receiving any treatment (shown with black continuous lines) as well as during treatment with tipifarnib and pirfenidone (gray dashed lines). The volume decrease occurred after patient had completed receiving any tumor-directed therapy. During the period of volume decrease, MRI signal intensity also decreased such that by age 17, the tumor appeared smaller and fainter compared with prior scans, but due to change in signal intensity volumetric analysis could no longer be performed. The decrease in volume was seen while patient was not receiving any tumor-directed therapy.

Discussion

This is the first study to comprehensively analyze and compare the longitudinal natural history of both PN and DNL growth in children and young adults with NF1. Our analysis revealed several crucial findings. First, we corroborated our previously reported association between age and estimated PN growth rates. Growth rates are variable between patients, with greater variability in younger patients such that rapid growing PNs are seen usually in younger patients and growth rate of ≥20%/year is uncommon in patients ≥18 years of age. Second, we characterized DNLs—a subgroup of PNSTs—that have different growth characteristics compared with PNs. In contrast to PNs, DNLs tend to develop later in life and tend to not have the same growth relationship to patient age as PNs. Third, we provide evidence that slow spontaneous tumor volume reduction may occur in PNs and DNLs, typically starting in adolescence or young adulthood.

For PNs, the volume change we observed was highly variable between patients but relatively consistent within a patient over extended periods of time, allowing the use of linear regression to estimate tumor growth rate. In a small subset (5 tumors), the treatment-free portion of growth was nonlinear. As rapid PN growth was typically observed in younger patients and was uncommon after adolescence, we anticipate that continued longitudinal follow-up on our study will identify other tumors that show nonlinear growth. Additional analyses of the entire period of follow-up that also assesses the effect of PN-targeted medical therapies on PN and DNL growth patterns are ongoing and may provide additional insight regarding change in growth rate over time. In a majority of patients, growth rate exceeded the rate of change in patient weight, suggesting that although some degree of PN volume increase may be related to the child’s general growth, tumor growth exceeds general anatomical growth in most children with NF1-associated PN, consistent with previous reports.3

We previously reported that increased FDG-PET avidity is localized to distinct nodular appearing lesions, some, but not all, of which show atypical features on pathology.17 Atypical neurofibromas are defined based on histopathological appearance and are thought to be precursor lesions for malignant transformation based on recent reports documenting cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A/B deletion in these lesions,23,24 and frequently show distinct nodular appearance on MRI.18 A new term, “atypical neurofibromatous neoplasms of uncertain biologic potential (ANNUBP),” with defined diagnostic criteria, has also been recently proposed for these tumors.25 Here we comprehensively analyzed the growth of both PNs and DNLs and provide evidence for key differences in the age of development and growth behavior between these tumors. These findings support DNLs and PNs being biologically different, and DNLs may represent areas concerning for malignant transformation. In our patient cohort, which was enriched for patients with large PN burden, DNLs were observed in 58/122 (45.6%) patients, with 31/58 having multiple DNLs. Further investigation is necessary to determine what proportion of DNLs are atypical neurofibroma or ANNUBP and therefore represent areas concerning for malignant transformation, as well as the timing of malignant transformation.

Lastly, we provide evidence of spontaneous tumor volume reduction in 10/113 (8.8%) PNs and 7/81 (8.6%) DNLs, typically starting in adolescence or young adulthood. Nguyen et al reported on growth rate of 200 individual PNs in 95 patients aged 1–64 years with median follow-up of 2.2 years (minimum 1.1, maximum 4.9 y) who were not receiving any PN-directed therapy, and found that in 71/200 tumors (35.5%) the volumes were smaller on follow-up compared with baseline, with a median change in volume of −3.4%/year (minimum −0.07%/y, maximum −35.9%/y). Growth rate was calculated for most of these patients (n = 140/171) based on only 2 time points, with a few tumors (n = 31/171) having 3 or 4 volume measurements. The authors felt that the lower measured tumor volume on follow-up could have been due to measurement error in some cases (but tumor shrinkage may have also occurred in some of the tumors) and that further studies would be required to clarify this.15 In our study, 47/113 (41.6%) PNs and 12/81 (14.8%) DNLs had a final volume that was less than the maximal volume during the entire period of follow-up. However, after excluding volume decreases noted while on tumor-directed therapies, and limiting volume decrease to ≥10% to exclude for potential measurement error, we were able to confirm spontaneous tumor volume reduction in 8.8% of PNs and 8.6% of DNLs. We anticipate that further follow-up will confirm spontaneous volume reduction in additional PNSTs in this ongoing study. In some cases, the tumor volume reduction was associated with decrease in T2 signal intensity on MRI (Fig. 4). Spontaneous tumor volume reduction occurred at a slow rate with no PN or DNL having ≥20%/year volume decrease, and was not seen in young children. This contrasts with volume decreases observed on the treatment trials with MEK inhibitors and in the phase II trial of cabozantinib.22,26,27

Limitations of our study are that the data collected on the natural history study has variable periods of follow-up for different patients and variable numbers and durations of systemic treatments during the observation period. To minimize potential treatment effect, the analysis focused on the first treatment-free portion of follow-up, which in some instances may not have been representative of the patient’s tumors’ entire follow-up period. Although many treatment trials were deemed ineffective, and many treatments appeared to have either no or only transient effects on the growth trajectory, the possibility of long-term effects of some of the therapies on tumor growth cannot be completely excluded. Additionally, in a small subset of patients (n = 5), the growth rate could not be estimated using linear regression as the growth pattern was nonlinear. Analysis was also limited by missing data for patients’ height and weight for a subset of patients and the analysis of relationship of growth rate to tumor location was limited by small sample sizes for extremity and whole-body PNs as well as DNLs located in the head and neck region. Many patients had multiple DNLs, and all the tumors were treated independently for associational analyses. However, it is possible that growth rates of multiple DNLs within a patient may be correlated. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insight into the growth behavior of PNSTs in children and young adults with NF1 given the large number of PNST studied and the long follow-up period with multiple serial volumetric MRIs. Continued longitudinal imaging and clinical evaluations of PNSTs and biologic studies on our NF1 natural history study are ongoing and will provide further insight.

Implications of our results for trial designs include that one should consider age, tumor volume at baseline, and tumor type (PN vs DNL) when designing trials or comparing results across trials. PN-directed treatments intended to slow growth may be more beneficial when started at younger age when rapid tumor growth may be seen. None of the tumors with confirmed spontaneous volume shrinkage had ≥20%/year decrease, suggesting that a decrease of >20%/year signifies a treatment effect in children and young adults with NF1. Additionally, future treatment trials should assess differences in responses of PNs and DNLs and assess DNL histology prospectively to better understand these lesions’ natural history and biologic potential.

Funding

This work was supported by the NCI intramural research program and a Neurofibromatosis Therapeutic Acceleration Program (NTAP) grant for partial salary support for SA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeffrey Solomon for development of volumetric analysis methods and technical support throughout the study.

Conflict of interest statement. None of the authors report any conflict of interest.

Authorship statement. SA, DJL, JOB, SMS, ED, BCW contributed significantly to the study design; SA, AB, DJL, AG, SMS, ED, BCW to the implementation; SA, AB, DJL, JOB, AMG, SMS, ED, and BCW to the analysis and interpretation of the data.

References

- 1. Korf BR. Plexiform neurofibromas. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89(1): 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nguyen R, Kluwe L, Fuensterer C, Kentsch M, Friedrich RE, Mautner VF. Plexiform neurofibromas in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: frequency and associated clinical deficits. J Pediatr. 2011;159:652–655.e652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dombi E, Solomon J, Gillespie AJ, et al. NF1 plexiform neurofibroma growth rate by volumetric MRI: relationship to age and body weight. Neurology. 2007;68(9):643–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim A, Gillespie A, Dombi E, et al. Characteristics of children enrolled in treatment trials for NF1-related plexiform neurofibromas. Neurology. 2009;73(16):1273–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mautner VF, Asuagbor FA, Dombi E, et al. Assessment of benign tumor burden by whole-body MRI in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10(4):593–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prada CE, Rangwala FA, Martin LJ, et al. Pediatric plexiform neurofibromas: impact on morbidity and mortality in neurofibromatosis type 1. J Pediatr. 2012;160(3):461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Uusitalo E, Rantanen M, Kallionpää RA, et al. Distinctive cancer associations in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(17):1978–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meany H, Widemannn B, Ratner N.. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: Prognostic and Diagnostic Markers and Therapeutic Targets. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nguyen R, Jett K, Harris GJ, Cai W, Friedman JM, Mautner VF. Benign whole body tumor volume is a risk factor for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in neurofibromatosis type 1. J Neurooncol. 2014;116(2):307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tucker T, Wolkenstein P, Revuz J, Zeller J, Friedman JM. Association between benign and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in NF1. Neurology. 2005;65(2):205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Canavese F, Krajbich JI. Resection of plexiform neurofibromas in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31(3):303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Needle MN, Cnaan A, Dattilo J, et al. Prognostic signs in the surgical management of neurofibroma: the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia experience, 1974–1994. J Pediatr. 1997;131:678–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gutmann DH, Blakeley JO, Korf BR, Packer RJ. Optimizing biologically targeted clinical trials for neurofibromatosis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22(4):443–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dombi E, Ardern-Holmes SL, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, et al. ; REiNS International Collaboration Recommendations for imaging tumor response in neurofibromatosis clinical trials. Neurology. 2013;81(21 Suppl 1):S33–S40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nguyen R, Dombi E, Widemann BC, et al. Growth dynamics of plexiform neurofibromas: a retrospective cohort study of 201 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tucker T, Friedman JM, Friedrich RE, Wenzel R, Fünsterer C, Mautner VF. Longitudinal study of neurofibromatosis 1 associated plexiform neurofibromas. J Med Genet. 2009;46(2):81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meany H, Dombi E, Reynolds J, et al. 18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) evaluation of nodular lesions in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 and plexiform neurofibromas (PN) or malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(1):59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higham CS, Dombi E, Rogiers A, et al. The characteristics of 76 atypical neurofibromas as precursors to neurofibromatosis 1 associated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(6):818–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Solomon J, Warren K, Dombi E, Patronas N, Widemann B. Automated detection and volume measurement of plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis 1 using magnetic resonance imaging. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2004;28(5):257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Neurofibromatosis. Conference statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(5):575–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lim R, Jaramillo D, Poussaint TY, Chang Y, Korf B. Superficial neurofibroma: a lesion with unique MRI characteristics in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(3):962–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dombi E, Baldwin A, Marcus LJ, et al. Activity of selumetinib in neurofibromatosis type 1-related plexiform neurofibromas. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(26):2550–2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beert E, Brems H, Daniëls B, et al. Atypical neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis type 1 are premalignant tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50(12):1021–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pemov A, Hansen NF, Sindiri S, et al. Low mutation burden and frequent loss of CDKN2A/B and SMARCA2, but not PRC2, define pre-malignant neurofibromatosis type 1–associated atypical neurofibromas. Neuro Oncol. 2019. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noz028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miettinen MM, Antonescu CR, Fletcher CDM, et al. Histopathologic evaluation of atypical neurofibromatous tumors and their transformation into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in patients with neurofibromatosis 1-a consensus overview. Hum Pathol. 2017;67:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fisher M. NF105: a Neurofibromatosis Clinical Trials Consortium (NFCTC) phase II study of cabozantinib (XL184) for neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) associated plexiform neurofibromas. 2018 Joint Global Neurofibromatosis Conference; 2018; Paris, France.

- 27. Weiss B, Plotkin S, Widemann B, et al. NF106: phase 2 trial of the MEK inhibitor PD-0325901 in adolescents and adults with NF1-related plexiform neurofibromas: an NF clinical trials consortium study. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(suppl_2):i143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.