Abstract

Early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD) is pathologically and clinically similar to the more common late-onset sporadic form of the disease. The study of rare genetic mutations that cause FAD should provide insight into the pathogenesis of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. FAD mutations have only been found in the substrate (amyloid precursor protein, APP) and protease (γ-secretase) that produces the amyloid-β peptide (Aβ). The secreted, aggregation-prone 42-residue Aβ peptide (Aβ42) has long been considered the pathogenic entity in Alzheimer’s disease. However, recent understanding of the complexity of the processing of APP by γ-secretase and the effects of FAD mutations on this processing suggests other forms of Aβ as potentially pathogenic.

Keywords: amyloid precursor protein, presenilin, proteolysis, mutations, membrane

Why Study Familial Alzheimer’s Disease?

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized pathologically by cerebral neurodegeneration, extracellular amyloid plaques, and intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles and clinically by the progressive loss of memory and cognitive function. The disease, however, is much more complex and heterogeneous than this brief description implies.1 AD typically strikes those over age 65, with frequent comorbidities.2 Genetics plays a role but is quite complicated.3 For these reasons, the pathogenic mechanisms of AD remain unclear, and no effective therapeutics have been identified.

Familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD) presents basic similarities to sporadic AD, but with important differences. Onset is in mid-life or earlier, and the genetics follows a dominant Mendelian pattern, with 100% penetrance in most pedigrees. Only three genes have been identified as associated with FAD: the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilin-1 and presenilin-2 (PSEN1 and PSEN2).4 Other than the hereditary nature and early onset, FAD is closely similar to the much more common sporadic late-onset AD with respect to pathology, presentation, and progression.

The idea of using rare genetic forms of a disease as a window into the molecular pathogenesis of more common sporadic cases is not new. Investigations into rare forms of cardiovascular disease led to understanding of the importance of cholesterol biosynthesis and transport to cardiovascular disease in the general population. This understanding ultimately resulted in the development of statins and other cholesterol-lowering drugs, which quickly ranked among the most prescribed medications. Moreover, the study of these rare genetic forms of hypercholesterolemia unveiled basic biology, for instance the process of endocytosis.

Biology and Pathobiology of γ-Secretase

The study of FAD has likewise borne fruit for basic biology and provided critical clues to pathogenesis. As the name indicates, APP is the precursor to the amyloid β-peptide that deposits in the AD brain. Successive proteolysis by β-secretase and γ-secretase results in release of secreted 38–43 residue Aβ peptides. Presenilin is the catalytic component of γ-secretase, a membrane protein complex also composed of three other subunits.5 Presenilin contains two conserved transmembrane aspartates that catalyze hydrolysis of the APP transmembrane domain within the lipid bilayer. Thus, FAD genes encode the substrate and the protease that produce Aβ.

γ-Secretase cleaves many other substrates besides APP, with more than 90 substrates identified.6, 7 Arguably the most important substrate is the Notch1 receptor, critical to cell-fate determinations in development and adulthood in all metazoans.8 Knockout of γ-secretase components results in lethal phenotypes remarkably similar to those seen upon Notch1 knockout.9, 10 Cleavage of Notch1 by γ-secretase is an essential component of its signaling mechanism, releasing the Notch1 intracellular domain for translocation to the nucleus and activation of transcription factors.11 Cleavage of certain other substrates by γ-secretase likewise results in cell signaling, but for most substrates the role of this protease appears to be clearance of membrane-bound protein stubs. For this reason, γ-secretase has been dubbed “the proteasome of the membrane”.12

These findings illustrate how the study of FAD has uncovered basic biology, including intramembrane proteolysis and elucidation of a central cellular and developmental signaling pathway. Yet despite the role of γ-secretase in signaling from Notch1 and other receptors and the many substrates cleaved by this protease, the only substrate mutated in FAD is APP. FAD mutations in APP are found in and around the small Aβ sequence and alter the properties and/or production of Aβ peptides.13 Fourteen FAD missense mutations are within the APP transmembrane domain near γ-secretase processing sites, and these mutations lead to increased proportions of the 42-residue form of Aβ (Aβ42) compared to the major Aβ variant Aβ40. Although a minor portion of secreted Aβ, Aβ42 is highly aggregation-prone14 and the major form deposited in AD plaques.15 Presenilin FAD mutations likewise alter APP proteolysis to increase the ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40.16

Reconsidering Aβ42

Aβ42 has been the lead candidate for the pathogenic entity—the molecular trigger—of AD for more than 25 years.17, 18 Nevertheless, there is no consensus on identity of the responsible Aβ42 assembly state, the nature of the neurotoxic signals, or the connection between pathological Aβ and tau.19, 20 Moreover, targeting Aβ has not led to effective therapeutic agents.21

The many clinical failures of anti-Aβ drug candidates may be due to intervening too late. Brain Aβ deposition can begin 15 years before and cerebrospinal fluid Ab42 can decrease 25 years before the appearance of symptoms.22 This observation coupled with the later spread of tau pathology suggests that even before clinical manifestation disease progression may become Aβ-independent and tau-driven.23 Intervention at the level of Aβ would be expected to have little effect if this is the case. Again targeting cholesterol for cardiovascular disease provides an analogy: treatment with statins should begin long before congestive heart failure is imminent.

Although the dearth of effective disease-modifying therapeutics may be explained by timing of intervention, the collective clinical failures over the course of nearly 20 years coupled with the many fundamental unknowns regarding pathogenic entities and mechanisms has led to disillusion with the amyloid hypothesis.24 Nevertheless, the genetics and biochemistry of FAD clearly point to aberrant proteolytic processing of APP substrate by γ-secretase as the triggering event in FAD.

A detailed understanding of the structural and functional changes in γ-secretase and its processing of APP substrate would seem to be critical for elucidating the pathogenesis of FAD and revealing strategies for developing prophylactic agents for FAD. Although FAD represents only 1–2% of all AD cases, this could be 50,000–100,000 FAD cases in the U.S. alone. Precision medicines for other, rarer genetic diseases have been successfully developed,25 and this should be both possible and worthwhile for FAD as well. FAD therapeutics might also prove effective for sporadic AD.

Processive Proteolysis and FAD

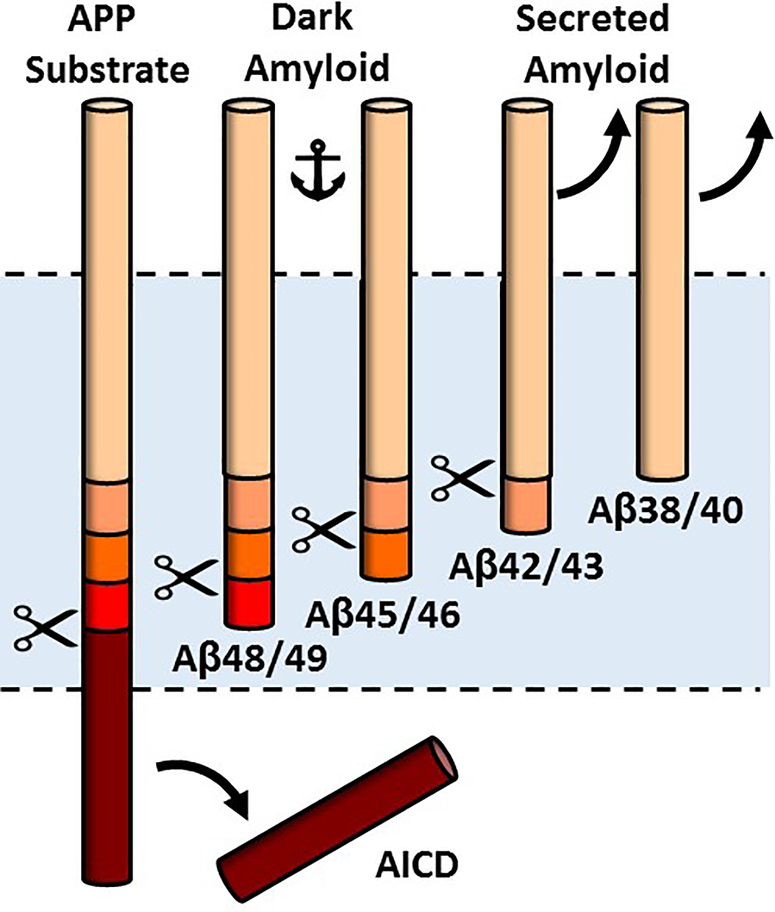

In recent years, the proteolytic processing of APP substrate by γ-secretase has been revealed to be much more complicated than previously imagined.26 The initial cut is near the cytoplasmic side of the APP transmembrane domain, releasing the APP intracellular domain and forming a 48- or a 49-residue Aβ peptide.27 These long Aβs contain most of the APP transmembrane domain and are not secreted. Instead, they are further proteolyzed by the γ-secretase complex, trimming them from the C-terminus in increments of three amino acids.28 Thus, two general pathways to secreted Aβ peptides are Aβ49→Aβ46→Aβ43→Aβ40 and Aβ48→Aβ45→Aβ42→Aβ38 (this last trimming event cleaves off four amino acids)(Fig. 1). Full confirmation of this carboxypeptidase activity of γ-secretase came with the detection and quantification of the tri- and tetrapeptide products by mass spectrometry.29

Figure 1.

Processive proteolysis of APP substrate by γ-secretase. Initial proteolysis releases the APP intracellular domain (AICD) and forms Aβ48 or Aβ49, which are subsequently trimmed along two pathways: Aβ49→Aβ46→Aβ43→Aβ40 and Aβ48→Aβ45→Aβ42→Aβ38. Peptide intermediates Aβ45 through Aβ48 contain most of the APP TMD and are membrane-anchored, while Aβ38 through Aβ43 are secreted. FAD mutations in g-secretase are deficient in carboxypeptidase activity and increase membrane-anchored Aβ peptides, dubbed here “dark amyloid”.

Presenilin FAD mutations are deficient in this carboxypeptidase activity.30–32 So far only a limited number of mutations have been examined at this levels, and it would seem to be critically important to determine if this is a common effect of FAD mutations, both in presenilins and APP. The deficient trimming of the mutants so far examined results not only in increased Aβ42 vis-à-vis Aβ40 but also in increased proportions of longer, membrane-anchored Aβ peptides ranging from 45 to 49 amino acids.30 Presenilin FAD mutations can also be deficient in the initial cleavage event, which can result in buildup of substrate, the 99-residue APP C-terminal fragment (C99).30 C99 also contains the entire Aβ sequence and can be thought of as a form of membrane-anchored Aβ.

Dark Amyloid

Normal or pathological roles of membrane-anchored Aβ peptides are completely unknown; to date they have only been considered as intermediates to the secreted peptides. I refer to these membrane-anchor Aβs as “dark amyloid” (Fig. 1). Like dark matter, they are difficult to detect, but they may have profound effects. As dark amyloid is located in the membrane, it is well positioned to trigger a toxic signal in the cell. This could occur through self-association, through interaction with other membrane proteins, or a combination of the two. Effects need not be cell-autonomous in neurons, but could for instance be produced in and trigger responses from glial cells, ultimately leading to synaptic dysfunction and neurotoxicity.

The pathogenic forms of Aβ in FAD may be distinct from the aggregated extracellular forms. Formation of Aβ42-containing plaques and oligomers could be epiphenomena occurring coincidentally with formation of the actual neurotoxic Aβ, which I posit here could be dark amyloid. However, roles for Aβ42 aggregates and membrane-anchored dark amyloid peptides are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, pathogenic roles for both extracellular aggregated and membrane-anchored prion protein appear to be operative in prion diseases.33

Criteria for pathogenic Aβ include the ability to elicit synaptic toxicity, tau pathology, and neurodegeneration, along with progressive loss of memory and cognitive function, all key features of AD and FAD. Aβ plaques do not meet these criteria. Aβo can cause synaptic toxicity along with inhibition of long-term potentiation and cognitive deficits in animal models,34, 35 but neither tau pathology nor neurodegeneration are observed. Thus, the AD phenotype is only partially recapitulated by Aβo. The search for alternative forms of Aβ as candidate pathogenic entities in AD and FAD would therefore seem appropriate.

Concluding comments

AD research is in a state of crisis, and there is the palpable sense that some fundamental piece in the puzzle of pathogenesis is missing. Thus, the field seems ripe for a paradigm shift, moving away from an old model that is no longer useful, as it is not leading to fundamental advances in either pathogenic mechanisms or effective therapeutics. Whether the concept of dark amyloid is key to such a paradigm shift remains to be seen. In any event, a focus on unraveling the effects of FAD mutations on γ-secretase processing of APP to elucidate pathogenesis of FAD is entirely appropriate.

References

- 1.Querfurth HW, and LaFerla FM (2010) Alzheimer’s disease, New Engl J Med 362, 329–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kovacs GG (2019) Are comorbidities compatible with a molecular pathological classification of neurodegenerative diseases? Curr Op Neurol 32, 279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pimenova AA, Raj T, and Goate AM (2018) Untangling Genetic Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease, Biol Psychiatry 83, 300–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanzi RE (2012) The genetics of Alzheimer disease, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2, pii: a006296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfe MS (2019) Structure and Function of the γ-Secretase Complex, Biochemistry, doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00401 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beel AJ, and Sanders CR (2008) Substrate specificity of γ-secretase and other intramembrane proteases, Cell Mol Life Sci 65, 1311–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemming ML, Elias JE, Gygi SP, and Selkoe DJ (2008) Proteomic profiling of γ-secretase substrates and mapping of substrate requirements, PLoS Biol 6, e257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kopan R, and Ilagan MX (2009) The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism, Cell 137, 216–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong PC, Zheng H, Chen H, Becher MW, Sirinathsinghji DJ, Trumbauer ME, Chen HY, Price DL, Van der Ploeg LH, and Sisodia SS (1997) Presenilin 1 is required for Notch1 and DII1 expression in the paraxial mesoderm, Nature 387, 288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen J, Bronson RT, Chen DF, Xia W, Selkoe DJ, and Tonegawa S (1997) Skeletal and CNS defects in Presenilin-1-deficient mice, Cell 89, 629–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Strooper B, Annaert W, Cupers P, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Mumm JS, Schroeter EH, Schrijvers V, Wolfe MS, Ray WJ, Goate A, and Kopan R (1999) A presenilin-1-dependent γ-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain, Nature 398, 518–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kopan R, and Ilagan MX (2004) γ-Secretase: proteasome of the membrane?, Nature reviews. Mol Cell Biol 5, 499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanzi RE, and Bertram L (2005) Twenty years of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid hypothesis: a genetic perspective, Cell 120, 545–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarrett JT, Berger EP, and Lansbury PT Jr. (1993) The carboxy terminus of the beta amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, Biochemistry 32, 4693–4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, and Ihara Y (1994) Visualization of Aβ42(43) and Aβ40 in senile plaques with end-specific Aβ monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is Aβ42(43), Neuron 13, 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duff K, Eckman C, Zehr C, Yu X, Prada CM, Perez-tur J, Hutton M, Buee L, Harigaya Y, Yager D, Morgan D, Gordon MN, Holcomb L, Refolo L, Zenk B, Hardy J, and Younkin S (1996) Increased amyloid-β42(43) in brains of mice expressing mutant presenilin 1, Nature 383, 710–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy J, and Allsop D (1991) Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease, Trends Pharmacol Sci 12, 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selkoe DJ (1991) The molecular pathology of Alzheimer’s disease, Neuron 6, 487–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benilova I, Karran E, and De Strooper B (2012) The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: an emperor in need of clothes, Nat Neurosci 15, 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marttinen M, Takalo M, Natunen T, Wittrahm R, Gabbouj S, Kemppainen S, Leinonen V, Tanila H, Haapasalo A, and Hiltunen M (2018) Molecular Mechanisms of Synaptotoxicity and Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease, Front Neurosci 12, 963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castellani RJ, Plascencia-Villa G, and Perry G (2019) The amyloid cascade and Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics: theory versus observation, Lab Invest, doi: 10.1038/s41374-019-0231-z. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, Marcus DS, Cairns NJ, Xie X, Blazey TM, Holtzman DM, Santacruz A, Buckles V, Oliver A, Moulder K, Aisen PS, Ghetti B, Klunk WE, McDade E, Martins RN, Masters CL, Mayeux R, Ringman JM, Rossor MN, Schofield PR, Sperling RA, Salloway S, and Morris JC (2012) Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease, New Engl J Med 367, 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jack CR Jr., Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Shaw LM, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Lesnick TG, Pankratz VS, Donohue MC, and Trojanowski JQ (2013) Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers, Lancet Neurol 12, 207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makin S (2018) The amyloid hypothesis on trial, Nature 559, S4–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyle MP, and De Boeck K (2013) A new era in the treatment of cystic fibrosis: correction of the underlying CFTR defect, Lancet Respir Med 1, 158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfe MS (2019) Dysfunctional γ-Secretase in Familial Alzheimer’s Disease, Neurochem Res 44, 5–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu Y, Misonou H, Sato T, Dohmae N, Takio K, and Ihara Y (2001) Distinct intramembrane cleavage of the β-amyloid precursor protein family resembling γ-secretase-like cleavage of Notch, J Biol Chem 276, 35235–35238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Funamoto S, Morishima-Kawashima M, Tanimura Y, Hirotani N, Saido TC, and Ihara Y (2004) Truncated carboxyl-terminal fragments of β-amyloid precursor protein are processed to amyloid β-proteins 40 and 42, Biochemistry 43, 13532–13540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takami M, Nagashima Y, Sano Y, Ishihara S, Morishima-Kawashima M, Funamoto S, and Ihara Y (2009) γ-Secretase: successive tripeptide and tetrapeptide release from the transmembrane domain of β-carboxyl terminal fragment, J Neurosci 29, 13042–13052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quintero-Monzon O, Martin MM, Fernandez MA, Cappello CA, Krzysiak AJ, Osenkowski P, and Wolfe MS (2011) Dissociation between the processivity and total activity of γ-secretase: implications for the mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease-causing presenilin mutations, Biochemistry 50, 9023–9035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandez MA, Klutkowski JA, Freret T, and Wolfe MS (2014) Alzheimer presenilin-1 mutations dramatically reduce trimming of long amyloid β-peptides (Aβ) by γ-secretase to increase 42-to-40-residue Aβ, J Biol Chem 289, 31043–31052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szaruga M, Veugelen S, Benurwar M, Lismont S, Sepulveda-Falla D, Lleo A, Ryan NS, Lashley T, Fox NC, Murayama S, Gijsen H, De Strooper B, and Chavez-Gutierrez L (2015) Qualitative changes in human γ-secretase underlie familial Alzheimer’s disease, J Exp Med 212, 2003–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chesebro B, Trifilo M, Race R, Meade-White K, Teng C, LaCasse R, Raymond L, Favara C, Baron G, Priola S, Caughey B, Masliah E, and Oldstone M (2005) Anchorless prion protein results in infectious amyloid disease without clinical scrapie, Science 308, 1435–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, and Selkoe DJ (2002) Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo, Nature 416, 535–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Townsend M, Cleary JP, Mehta T, Hofmeister J, Lesne S, O’Hare E, Walsh DM, and Selkoe DJ (2006) Orally available compound prevents deficits in memory caused by the Alzheimer amyloid-βoligomers, Ann Neurol 60, 668–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]