Abstract

Objective. To compare first-year student pharmacists and nursing students with respect to their spirituality and perceptions of the role of spirituality in professional education and practice.

Methods. This was a five-year, cross-sectional study. All first-year student pharmacists and nursing students were invited to participate in the survey during the first week of the fall semester in 2012 through 2016. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data.

Results. A total of 1,084 students participated, including 735 student pharmacists and 349 nursing students. Significant differences in baseline demographics were noted between the groups. Students in both groups reported having frequent spiritual experiences. A significantly larger percentage of nursing students reported these experiences compared to student pharmacists. Furthermore, compared with student pharmacists, nursing students were more likely to anticipate that spirituality would play a role in their academic course work (76% vs 58%) and professional practice (90% vs 74%).

Conclusion. Student pharmacists and nursing students reported having frequent spiritual experiences, and both groups anticipated that spirituality would be incorporated into their education and professional practice.

Keywords: spirituality, religion, student pharmacist, nursing student, professional education

INTRODUCTION

Spirituality has played a critical role in the historical development of medicine. Several health systems in the United States originated from medical services provided by individuals who were inspired by religious beliefs.1,2 Studies have shown both positive and negative associations between religious practices and various medical conditions.3-8 In addition, many patients have expressed the desire that aspects of spiritual care be incorporated into the medical care they receive.9,10 Several validated scales are available to aid health care providers in performing spiritual assessments and taking patients’ spiritual histories.11-13 Pharmacists and nurses are on the front lines of health care delivery and have closely aligned goals for optimizing patient care. Some reports indicate nursing, along with medicine, has been at the forefront in recognizing the importance of spiritual care as a component of patient care in professional degree programs.14-17 While pharmacy accreditation standards make no specific mention of spirituality, they do emphasize key competencies, such as cultural sensitivity, communication, and patient advocacy, which can all be influenced by a person’s spiritual commitments.18 It is unclear how members of the pharmacy and nursing professions compare with respect to perceptions on the role of spirituality as an aspect of professional education and patient care.

Only a few studies have evaluated student pharmacists’ perceptions regarding the role of spirituality in pharmacy education.19-21 Jacob and colleagues found that incoming student pharmacists anticipated that matters of spirituality would be components of the pharmacy curriculum and their future professional practice.19 Furthermore, nearly 90% of students in the study believed that a general understanding of the role of spirituality in society was useful in order to be fully prepared for pharmacy practice. This belief was expressed by students with and without a personal religious affiliation.

Compared to pharmacy research literature, there is a significantly greater extent of research evaluating the perceptions of nursing students related to spirituality in the context of providing patient care. No published studies have compared student pharmacists with nursing students on measures of spirituality or perceptions regarding the role of spirituality in higher education and professional practice. The objective of this study was to measure spirituality among first-year student pharmacists and nursing students and to compare both groups of students with respect to measures of spirituality and perceptions regarding the role of spirituality in academic course work and future professional practice.

METHODS

This was a five-year, cross-sectional study. Some aspects of the methods have been previously described.19 An electronic survey was administered to participants. The survey included the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES), Duke Religion Index (DUREL), and five additional questions regarding perceptions on the role of spirituality in education and professional practice. The DSES and DUREL are validated survey instruments that measure spirituality. The DSES contains 16 items designed to measure ordinary daily spiritual experiences, while being inclusive of individuals with diverse theistic or nontheistic beliefs.22 The first 15 items of the DSES ask respondents to rate the frequency of various spiritual experiences using six response choices ranging from “many times a day” to “never or almost never.” The final question asks respondents to self-assess their perceived closeness to God or what they consider as divine using four response choices ranging from “as close as possible” to “not close at all.” The scale includes instructions to the participant stating that if they are not comfortable with the use of the word “God,” they may substitute another word appropriate for their spiritual commitments or practices. The DUREL is a five-item scale that was designed to be a measure of spirituality and religiosity in epidemiological studies.23 The instrument measures organizational religious activity, non-organizational religious activity, and intrinsic religiosity. Two of the questions asked respondents to rate their frequency of participation in various religious activities. The remaining items asked respondents to indicate the extent to which three statements about religious beliefs or experience described them by choosing one of five responses ranging from “definitely true of me” to “definitely not true of me.”

In addition to the two validated scales, the investigators developed five additional questions to evaluate students’ perceptions of the anticipated role of spirituality in higher education and their eventual professional practice. The authors did not provide a specific definition of spirituality for participants in order to ensure that the study remained as open and inclusive as possible and to encourage maximum student participation. The five questions addressed the impact of personal spirituality on the decision to pursue a career in pharmacy or nursing, the anticipated role spirituality would have in academic course work and future practice settings, and their perceptions regarding the importance of understanding spirituality as a means of improving the ability to function successfully as a pharmacist or nurse. Responses were based on a four-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree).

The complete survey instrument was offered to all entering first-year student pharmacists and nursing students during the first week of the fall semester from 2012 to 2016. Students were enrolled at a private institution for higher education in the southeastern United States. The university maintains a strong embrace of intellectual and religious freedom. Of note, the College of Nursing has a historical association with the Baptist tradition, which is reflected in its name. The college embraces various core values, including Christian caring, which they define as a commitment to value and support all persons.

The survey was delivered using a data collection and analysis software program designed by Qualtrics (Qualtrics Labs, Provo, UT). Students received an electronic link to the survey with a request to complete the survey. In addition, students were given approximately 15 minutes during orientation or class to complete the survey. Participation in the study was voluntary and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Investigational Review Board approval was obtained from the study institution.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe all baseline demographic questionnaire items. Categorical variables were characterized by count and percentage for the DSES, the DUREL, and the internally developed questionnaire on student perceptions. To determine differences in pharmacy and nursing categorical variables, the chi-square test was used. The a priori level of significance was set at .05. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics, version 21.0 and version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

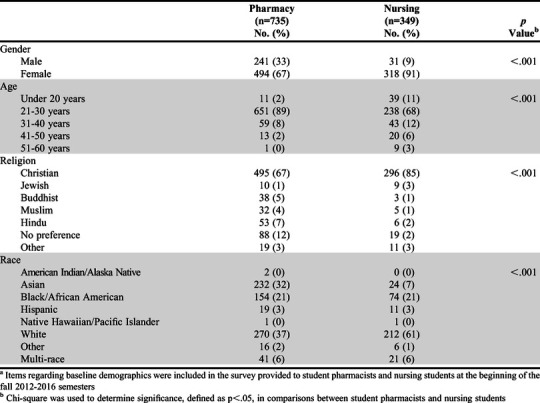

A total of 1,084 students (response rate=70%) participated over the five-year study period, including 735 student pharmacists (response rate=93%) and 349 nursing students (response rate=46%). The breakdown of student pharmacist participants by year was as follows: 2012 (n=153), 2013 (n=149), 2014 (n=134), 2015 (n=145), and 2016 (n=154). The breakdown of nursing student participants by year was as follows: 2012 (n=110), 2013 (n=19), 2014 (n=50), 2015 (n=122), and 2016 (n=48). Most participants were female (75%) and from 21 to 30 years of age (82%). As shown in Table 1, there were significant differences between groups in gender, age, religious affiliation, and race/ethnicity.

Table 1.

Demographics of Student Pharmacists and Nursing Students Who Participated in a Survey to Determine Their Perception of the Role of Spirituality in Their Professional Education and Future Practicea

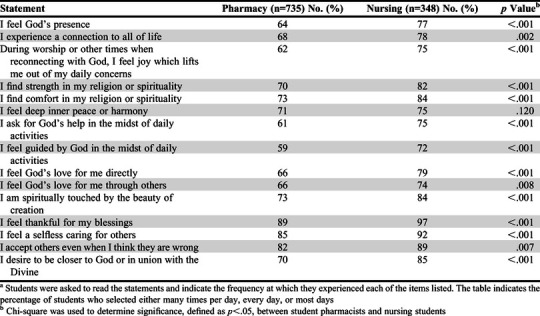

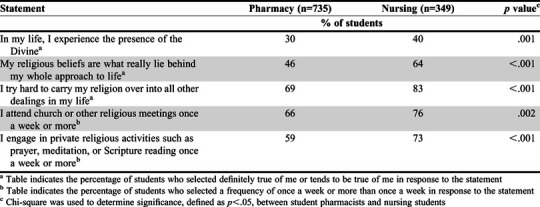

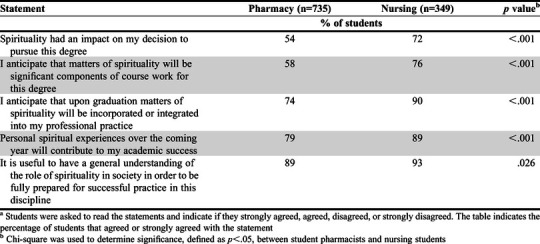

Measures of spirituality for student pharmacists and nursing students as assessed by the DSES and DUREL are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The spiritual experiences most reported by both groups included feeling thankful for blessings, feeling a selfless caring for others, and accepting others even when they disagreed with them. The degree of spiritual engagement was high in both groups; however, the percentage of nursing students who reported spiritual experiences was greater than the percentage of student pharmacists for all measures of spirituality assessed by the DSES except for feeling deep inner peace and harmony. In addition, the percentage of student pharmacists who rated themselves very close or as close as possible to God was significantly lower than the percentage of nursing students (49% vs 64%, p<.001). In addition, student pharmacists were less likely to engage in organizational and non-organizational religious activities. Nearly all the students believed that a general understanding of the role of spirituality in society was important to be fully prepared for practice as a pharmacist or nurse. However, a significantly higher percentage of nursing students anticipated spirituality to be a part of future academic course work and professional practice (Table 4).

Table 2.

Student Pharmacists and Nursing Students Responses on the Daily Spiritual

Table 3.

Duke Religion Index26

Table 4.

Students’ Perceptions Regarding the Role of Spirituality in Education and Professional Practicea

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to compare student pharmacists and nursing students with respect to spirituality using validated survey instruments and to evaluate differences in students’ perceptions on the role of spirituality in education and professional practice. Pharmacy and nursing are among the oldest and most trusted professions within health care and have shared goals as it relates to patient care, making them ideal for comparisons when examining questions related to spirituality, professional education, and health care delivery. In this study, students from both professions had frequent engagement with spiritual experiences and a high degree of anticipation for the role of spirituality in education and practice. In addition, many of the spiritual experiences attested to by these students have potential implications for health care delivery from the pharmacy and nursing perspective. A relatively high proportion of both groups of students expressed that religious views permeate much of their approach to life. Furthermore, students almost universally expressed the view that understanding the role of spirituality in society is an important aspect of developing into an effective practitioner. Students’ perceptions and personal spiritual experiences may influence the quality and nature of care they provide to patients.

This study adds to the limited pedagogical research focusing on the spirituality of students in health care disciplines. The first landmark study of spirituality in higher education by Astin and colleagues in 2009 included 14,527 undergraduate students attending 136 colleges and universities across the United States.33 Unfortunately, similar large-scale studies involving students in professional health care programs have not been conducted. Purnell and colleagues measured religiosity among student pharmacists using the DUREL. They reported that student engagement with organizational religious activities was a few times annually (median score 3.0) and with non-organizational religious activities was less than once weekly (median score 2.5).21 The religious engagement of students in our study appeared to be higher because a majority of student pharmacists (66%) and nursing students (76%) reported being involved in organized religious activities every week or more. In addition, most student pharmacists (59%) and nursing students (73%) reported engagement in private, non-organizational religious activity at a frequency of weekly or greater. This apparent greater engagement with religious activities may be explained by differences between the studies in response rates, baseline demographic characteristics, and the sociocultural differences in geographic regions. In both studies, measures of intrinsic religiosity appeared to be high. The DSES has been used sparsely for evaluation of spirituality among students in health science disciplines. Taylor and colleagues found that DSES scores improved in a study of 201 nursing students and nurses who participated in a self-study program related to the provision of spiritual care.34 Spiritual engagement of the students in our study was similar to what Wehmer and colleagues reported after evaluating 126 nursing students. Being thankful for blessings was the most frequent spiritual experience reported by participants followed by having a desire to be closer to God and a selfless caring for others.35 We suggest that further studies be conducted among students in pharmacy and nursing to evaluate their spirituality using the DSES.

Pharmacy and nursing students’ positive disposition toward matters of spirituality in professional education and patient care builds on similar findings from previous studies, albeit limited in their scope, involving students from pharmacy and other health care disciplines. In our study, nearly 75% of student pharmacists and 90% of nursing students expected to incorporate spirituality into their future professional practice. Similarly, in a 2003 study, Cooper and colleagues found that approximately 90% of student pharmacist leaders from across the country believed that spirituality has an impact on health.20 More recently, Purnell and colleagues evaluated final-year student pharmacists and reported that they believed that a patient’s spirituality and/or religiosity can have an impact on their overall health (88%) and medication adherence (76%).21 Guck and Kavan found that medical students had a positive appreciation for the role of spirituality in helping patients with acute, chronic, terminal, and mental illnesses.24 Several studies across geographic regions have found positive nursing student perceptions regarding the role of spirituality in patient care.25-29 Interestingly, some studies among nursing students also concluded there was a need for improvement in competencies regarding the spiritual aspects of health care.27-28,30 In a prospective, multi-site study involving 2,193 nursing and midwifery students, Ross and colleagues found that a broad view of what encompasses spirituality and high personal engagement in spirituality appears to correlate best with self-perceived competence in providing spiritual care to patients.31 Similarly, Damiano and colleagues evaluated 106 medical students in the United States and found that spiritual openness was predictive of empathy scores.32 Our study suggests that both pharmacy and nursing students see matters of spirituality as being integral to patient care; however, this impression appears to be stronger among nursing students. Further research is warranted to determine whether these perceptions lead students to see connections between matters of spirituality and patient care during their professional education. It remains to be determined whether students’ perceptions change over time and whether potential changes differ based on the discipline of study.

The shared anticipation we identified in student pharmacists and nursing students regarding the role of spirituality in health professions education should encourage educators to consider how and where spirituality can be effectively implemented within interprofessional education (IPE) initiatives. Over the past several years, there has been heightened interest in implementing IPE.36,37 Interprofessional education emphasizes creating opportunities for two or more professions, like pharmacy and nursing, to learn with, from, and about each other with the goal of increasing collaboration between the profession and improving the quality of care.38 Pharmacists often work closely with nurses in a variety of health care settings, including inpatient units, ambulatory care clinics, and long-term care facilities, where issues of spirituality are likely to arise. Pedagogical literature regarding incorporation of spirituality in IPE is limited, and no studies have included student pharmacists.39,40 Only two published studies describe curricular offerings related to spirituality and health for student pharmacists.41,42 Spirituality in health care provides a unique topic that could foster IPE activities and discussions in both didactic and experiential settings. The opportunities for incorporating student pharmacists in IPE activities related to spirituality appear plentiful. There are several scenarios where spirituality may arise specifically in relation to discussions about pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, including therapeutic lifestyle modifications, use of blood products, contraception, palliative care, and mental health. Pharmacy faculty members should evaluate opportunities, including in IPE, to incorporate discussions on spirituality and health in pharmacy curricula.

Pedagogical and clinical research related to the role of spirituality in pharmacy is limited. There are over 400 published studies that examine nursing students and various aspects of spirituality, compared to only a few studies that have evaluated similar questions in pharmacy pedagogy.19-21 Moreover, only a few studies have specifically evaluated the role of practicing pharmacists in providing spiritual care.43-46 The relative lack of research on spirituality from a pharmacy perspective is a missed opportunity for the profession to contribute to this burgeoning area of scholarship. Notably, there is a minimal amount of scholarship specifically related to the role of spirituality or religious beliefs in influencing pharmacotherapy choices and response. This is an area where pharmacists should develop expertise. There are several potential research questions related to spirituality and implementation of spiritual care for patients that could be asked from the perspective of the pharmacist. For example, what role does spirituality play in promoting or hindering medication adherence and how can the pharmacist use this information for drug therapy optimization? Educators could develop appropriate methods to measure student pharmacists’ preparedness to engage with patients when issues related to spirituality arise during discussions of acute or chronic disease management. Another research question might focus on evaluating whether currently accepted instruments for performing a spiritual assessment meet the needs of pharmacists or whether alternative approaches are warranted. Increased scholarship provides an opportunity for pharmacy to join the accelerating recognition that holistic care for patients includes addressing the spiritual aspects of health and wellness.

There are limitations worth noting regarding this study. First, participants were enrolled at a single institution and the nursing school has a historical religious association. Furthermore, students were from a narrow geographic region, which may have influenced baseline perceptions regarding spirituality. The findings cannot be extrapolated to other regions and would need to be confirmed in a more geographically diverse selection of schools. The high response rate among student pharmacists (93%) was not matched among nursing students (46%). This is most likely because of the change in nursing faculty participation on the study team during the study and the logistic challenges of coordinating in-class time for students to complete the survey. Also, because participation was voluntary, spiritually or religiously inclined students might have been more likely to complete the survey. Additionally, there were significant differences between the groups in demographic characteristics. While this is not unusual for this type of study, it may contribute to differing responses to the survey questions. Finally, language in the DSES and DUREL may reflect an implicit bias toward Christianity, which possibly influenced responses.

The term spirituality avoids prejudicing the communal and social aspects of religious membership or belonging over the psychological, cognitive, and emotional aspects of individual religious experience. Spirituality therefore invokes a broader sense of religious experience that resonates with a wider range of students, regardless of their religious affiliation. We also acknowledge that many individuals find that the terms spirituality and religiosity need not be associated. Our focus on perceptions of spirituality prioritizes the function of spirituality over its essence. Regardless of how students define spirituality, understanding that spirituality informs students’ lives and expectations of their professions will be the first step in determining whether there is a need to adapt curricular or extracurricular offerings to address these expectations.

CONCLUSION

The student pharmacists and nursing students who participated in this study had frequent spiritual experiences as measured by validated survey instruments. Furthermore, both groups of students anticipated that spirituality would be incorporated into their academic course work and future professional practice. These findings add to the limited pedagogical literature showing that these groups of students have positive impressions regarding the role of spirituality in education and practice. Expanded scholarship from the pharmacy perspective on the role of spirituality in education and practice is warranted.

Experiences Scalea, 25

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Kathryn Momary, PharmD, Nader Moniri, PhD, and Gina Ryan, PharmD, CDE, for their contributions in reviewing this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Puchalski CM. Religion, medicine and spirituality: what we know, what we don’t know and what we do. Asian Pac J Cancer . 2010;11 Suppl 1:45-49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Numbers RL, Amundsen DW. Caring and Curing – Health and Medicine in the Western Religious Traditions. Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien B, Shrestha S, Stanley MA, et al. Positive and negative religious coping as predictors of distress among minority older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry . 2019;34(1):54-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones KF, Pryor J, Care-Unger C, Simpson GK. Spirituality and its relationship with positive adjustment following traumatic brain injury: a scoping review. Brain Inj . 2018;32(13-14):1612-1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris WS, Gowda M, Kolb JW, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effects of remote, intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients admitted to the coronary care unit. Arch Intern Med . 1999;159(19):2273-2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boelens PA, Reeves RR, Replogle WH, Koenig HG. The effect of prayer on depression and anxiety: maintenance of positive influence one year after prayer intervention. Intl J Psych Med . 2012;43(1):85-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smothers ZPW, Koenig HG. Spiritual interventions in veterans with PTSD: a systematic review. J Relig Health . 2018;57(5):2033-2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koenig HG. Medicine, Religion, and Health – Where Science and Spirituality Meet . West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green CA. Complimentary care: when our patients request to pray. J Relig Health . 2018;57(3):1179-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minton ME, Isaacson M, Banik D. Prayer and the registered nurse: nurses’ reports of ease and disease with patient-initiated prayer request. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(9):2185-2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puchalski CM, Ferrell B. Making Health Care Whole – Integrating Spirituality Into Patient Care. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young C, Koopsen C. Spirituality, Health, and Healing – An Integrative Approach. 2nd ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saguil A, Phelps K. The spiritual assessment. Am Fam Physician . 2012;86(6):546-550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stern J, James S. Every person matters: enabling spirituality education for nurses. J Clin Nurs . 2006;15(7):897-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pesut B. Developing spirituality in the curriculum: worldviews, intrapersonal communication, interpersonal connectedness. Nurs Educ Perspect . 2003;24(6):290-294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lantz CM. Teaching spiritual care in a public institution: legal implications, standards of practice, and ethical obligations. J Nurs Educ . 2007;46(1):33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puchalski CM, Blatt B, Kogan M, Butler A. Spirituality and health: the development of a field. Acad Med. 2014;89(1):10-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Key Elements for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree (“Standards 2016”). Published February 2015. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2020.

- 19.Jacob BC, White A, Shogbon AO. First year student pharmacists’ spirituality and perceptions regarding the role of spirituality in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ . 2017;81(6):Article 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper JB, Brock TP, Ives TJ. The spiritual aspect of patient care in the curricula of colleges of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ . 2003;67(2):Article 44. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purnell MC, Johnson MJ, Jones R, et al. Spirituality and religiosity of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ . 2019;83(1):Article 6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Underwood LG. The daily spiritual experiences scale: overview and results. Religions . 2011;2(4):29-50. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koenig HG, Bussing A. The Duke University religion index (DUREL): a five-item measure for use in epidemiological studies. Religions. 2010;1(1):78-85. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guck TP, Kavan MG. Medical student beliefs: spirituality’s relationship to health and place in medical school curriculum. Med Teach . 2006;28(8):702-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiew LH, Creedy DK, Chan MF. Student nurses’ perspectives of spirituality and spiritual care. Nurs Educ Today . 2013;33:574-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruz JP, Alshammari F, Alotaibi KA, Colet PC. Spirituality and spiritual care perspectives among baccalaureate nursing students in Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. Nurs Educ Today . 2017;49:156-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalkim A, Sagkal Midilli T, Daghan S. Nursing students’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care and their spiritual care competencies: a correlational research study. J Hosp Palliat Nurs . 2018;20(3):286-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cordero RD, Romero BB, de Matos FA, et al. Opinions and attitudes on the relationship between spirituality, religiosity, and health: a comparison between nursing students from Brazil and Portugal. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(13-14):2804-2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez V, Fischer I, Leigh MC, Larkin D, Webster S. Spirituality, religiosity, and personal beliefs of Australian undergraduate nursing students. J Transcult Nurs . 2014;25(4):395-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daghan S. Nursing students’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care: an example of Turkey. J Relig Health . 2018;57:420-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross L, McSherry W, Giske T, et al. Nursing and midwifery students’ perceptions of spirituality, spiritual care, and spiritual care competency: a prospective, longitudinal, correlational European study. Nurse Educ Today . 2018;67:64-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Damiano RF, DiLalla LF, Lucchetti G, Dorsey JK. Empathy in medical students is moderated by openness to spirituality. Teach Learn Med . 2017;29(2):188-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Astin AW, Astin HS, Lindholm JA. Cultivating the spirit: how college can enhance students’ inner lives. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor EJ, Mamier I, Bahjri K, Anton T, Petersen F. Efficacy of a self-study programme to teach spiritual care. J Clin Nurs . 2009;18(8):1131-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wehmer MA, Quinn Griffin MT, White AH, Fitzpatrick JJ. An exploratory study of spiritual dimensions among nursing students. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh . 2010;7:Article 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. Washington, DC. Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2016.

- 37.Grice GR, Thomason AR, Meny LM, Pinelli NR, Martello JL, Zorek JA. Intentional interprofessional experiential education. Am J Pharm Educ . 2018;82(3):Article 6502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barr H, Low H. Introducing interprofessional education. Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE). July 2013. https://www.caipe.org/resources/publications/caipe-publications/barr-h-low-h-2013-introducing-interprofessional-education-13th-november-2016. Accessed August 26, 2020.

- 39.Ellman MS, Schulman-Green D, Blatt L, et al. Using online learning and interactive simulation to teach spiritual and cultural aspects of palliative care to interprofessional students. J Palliat Med . 2012;15(11):1240-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lennon-Dearing R, Florence JA, Halvorson H, Pollard JT. An interprofessional educational approach to teaching spiritual assessment. J Health Care Chaplain . 2012;18(3-4):121-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell J, Blank K, Britton ML. Experiences with an elective in spirituality. Am J Pharm Educ . 2008;72(1):Article 16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dugan BD, Kyle JA, Kyle CW, Birnie C, Wahba W. Integrating spirituality in patient care: preparing students for the challenges ahead. Curr Pharm Teach Learn . 2011;3(4):260-266. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daher M, Chaar B, Saini B. Impact of patients’ religious and spiritual beliefs in pharmacy: from the perspective of the pharmacist. Res Social Adm Pharm . 2015;11(1):e31-e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenbaum CC. The role of the pharmacist – prayer and spirituality in healing. Ann Pharmacother . 2007;41(3):505-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higginbotham AR, Mary TR. Spiritual assessment: a new outlook in the pharmacist’s role. Am J Health Syst Pharm . 2006;63(2):169-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davidson LA, Pettis CT, Joiner AJ, Cook DM, Klugman CM. Religion and conscientious objection: a survey of pharmacists’ willingness to dispense medications. Soc Sci Med . 2010;71(1):161-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]