Abstract

Objective. To determine the discourses on professional identity in pharmacy education over the last century in North America and which one(s) currently dominate.

Methods. A Foucauldian critical discourse analysis using archival resources from the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education (AJPE) and commissioned education reports was used to expose the identity discourses in pharmacy education.

Results. This study identified five prominent identity discourses in the pharmacy education literature: apothecary, dispenser, merchandiser, expert advisor, and health care provider. Each discourse constructs the pharmacist’s professional identity in different ways and makes possible certain language, subjects, and objects. The health care provider discourse currently dominates the literature. However, an unexpected finding of this study was that the discourses identified did not shift clearly over time, but rather piled up, resulting in students being exposed to incompatible identities.

Conclusion. This study illustrates that pharmacist identity constructs are not simple, self-evident, or progressive. In exposing students to incompatible identity discourses, pharmacy education may be unintentionally impacting the formation of a strong, unified healthcare provider identity, which may impact widespread practice change.

Keywords: professional identity, pharmacy, pharmacy practice, pharmacy education, Focauldian discourse analysis

INTRODUCTION

Professional identity formation, which is the development of professional values, actions, and aspirations, is gaining momentum as a movement for health professions educational reform.1-5 Nowhere is this movement stronger than in medical education.1-3 In 2010, the Carnegie Foundation brought the issue to the forefront, stating: “professional identity formation should be the backbone of medical education.”6 Similar development in pharmacy education is lagging behind.4,7-9 The paucity of research exploring professional identity in pharmacy makes it difficult for educators to incorporate identity formation into curricula effectively.7 Yet it is more important than ever that pharmacists embody a clear identity, as boundaries and scopes of practice are continuously being renegotiated, and if not careful, pharmacists risk losing their professional status.10-12 A solid professional identity can facilitate the internal regulation of pharmacists, as well as enable confidence for members to practice effectively.11-13 The increased emphasis on professional identity formation in health professions education, combined with the lack of research specific to pharmacy, present an opportunity to redefine the 21st century pharmacist.

Pharmacy is a profession with a long history of status, power, and societal importance.7,12-15 However, it has been challenged over the last century as most of its traditional roles have changed significantly due to societal transformations such as mass manufacturing of pharmaceuticals and the widespread public availability of drug information.15,16 The profession is continuously reconstructing and predominantly relying on pharmacy education and the renewal of pharmacy curricula as its change agents.7,17 This is evidenced by significant curricular changes across North America and the United Kingdom (UK), resulting in Doctor of Pharmacy degrees (PharmD) and Master of Pharmacy degrees (MPharm) as entry to practice requirements.18-21 The driving force is the development of a new breed of “patient-centered, clinical pharmacists,” with the focus mainly on professionalism and professional values, which alone are insufficient for the formation of a professional identity.4,8,9 Recent research suggests that pharmacy graduates are unable to enact patient-centered ways of being a pharmacist,22-24 suggesting that reconstructing a professional identity is more complex than curricular reform alone.7,8 Evidence suggests that pharmacy students do not have strong perceptions of their professional identity.25,26 Morison and O’Boyle compared first-year nursing, medicine, dental, and pharmacy students’ perceptions of the professional identity of their respective disciplines.25 Pharmacy students struggled to identify roles that made their profession distinct. While nursing and medicine students had clear ideas about what it meant to belong to their profession, pharmacy students struggled to describe belonging and explained their identities by how they differed from medicine. Pharmacy students had a stronger grasp of a doctor’s role than of their own future professional role.25 This may, in part, be a result of the lack of a common professional identity within pharmacy in contrast to a clearer and commonly accepted professional identity within a field such as medicine.25,26

Unfortunately, the story is no different in practice. Practicing pharmacists continue to grapple with their identity and unique contribution to the health care system.10,24,27 Elvey and colleagues have noted that “pharmacists have been variously characterized as makers of medicine, as pill pushers, pill counters and bottle labellers, as health advisers, as medicine experts, as managers, as entrepreneurs, as public health experts, as clinicians, and as substitutes for general practitioners.”10 This high number of identities suggests confusion within the profession itself, and likely contributes to role ambiguity and pharmacy students’ lack of clear ownership of what pharmacists should contribute to the health care system.10 Without a better understanding of its identity, the pharmacy profession is at risk of being perpetually caught in the hamster wheel of identity evolution: constantly seeking a new role, but never knowing when they have arrived.

Pharmacy has an opportunity to learn from its storied past and transform itself to meet the challenges of today’s health care practice, or risk becoming obsolete. By exploring pharmacists’ identities of the past, new possibilities for future identities can be made visible. The objectives of this study were to explore the professional identity discourses in pharmacy education over the last century in North America and determine which one(s) currently dominate.

METHODS

This study was theoretically informed by the works of Michel Foucault, a prominent French scholar whose perspectives can be of significant value to framing health professions education research.28-31 Foucault wrote actively between 1960-1980, with famous works covering topics such as the birth of clinical medicine, psychiatry, and many other areas.28,30,31 His research methodology was historical and archival in nature 28,32 and was associated with numerous concepts and ideas, including discourse and discourse analysis. 30-33

Critical discourse analysis regards language as a social practice.35,36 It takes particular interest in the relation between language and power.35 A fully critical account of discourse requires a theorization and description of both the social processes and structures that give rise to the production of a text, and of the social structures and processes within which individuals or groups create meanings in their interaction with texts, also known as archives.37 Consequently, three concepts figure indispensably in all critical discourse analysis: the concept of power, the concept of history, and the concept of ideology.35

For this study, a Foucauldian informed critical discourse analysis was used because it allows for the examination of language and practices of pharmacists and institutions (universities, hospital pharmacy, community pharmacy) with the goal of understanding how these practices shape and limit the ways that individuals and institutions can think, speak, and conduct themselves.33,35,37 As noted by Hodges and colleagues, to undertake a Foucauldian discourse analysis is to study “how particular discourses construct, systematically, different versions of the social world.”28 This involves the analysis of text and language, but also the examination of the roles of individuals and institutions that are made possible by particular ways of thinking and seeing the world.28,34 The goal is to study constructs that might be considered “natural” in order to show how each is, in fact, a product of specific power/knowledge relationships founded on a series of repeated and legitimized statements, known as truth statements.28,34 The examination of truth statements allows for better understanding of what is taken for granted at different points in history, thus allowing for reimagination of possibilities. Foucault believed that discontinuities in knowledge appeared at different points in time, with no single “truth” being better or worse than another.31,36

The concept of archaeology, according to Foucault, involves digging up bits of language to reconstruct ideas and practices of the past as well as the present.34 This approach to discourse analysis is useful as it helps to focus attention on the way truths have been used in different ways at different times. In this approach, changes or ruptures in the kinds of statements being made are important as they signal shifts in ways of thinking and in the rules governing discourse production.34 This is important as discourses encompass elements beyond ways of thinking and speaking, including the roles people can play, the institutions that govern, and the different object and subject positions.34 For this analysis, the term subjects referred to the social construction of individuals or collectives who felt, thought, and acted in certain ways as a result of the discourse.32 Objects referred to the material things that were made possible as a result of the discourse.32 Overall, a Foucauldian approach allows one to challenge assumptions, thus creating opportunities for alternative ways of seeing the issues at hand.

Data Sources and Analysis

A Foucauldian critical discourse analysis requires an archive be created for analysis purposes. In a Foucauldian sense, an archive is “the general system of the formation and transformation of statements.”32,38 More simply put, the archive is the collection of historical artifacts (ie, texts) that contain the discourses to be investigated.32 The archive was limited to publications in the Journal from its inception in 1937, plus key reports commissioned by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) and publications of the Association of Faculties of Pharmacy of Canada (AFPC) published since 1900. The key commissioned reports included were: Basic Material for a Pharmaceutical Curriculum,39 The Pharmaceutical Survey,40,41 Pharmacists for the Future,42 and The Commission to Implement Change in Pharmaceutical Education.43 These sources were chosen specifically as they represent key voices, organizations, and publications in pharmacy education, and thus reflect important conversations of the time, but balance size and robustness of included materials.

To compile the archive for analysis, the table of contents for each issue of the Journal was reviewed. Any articles, editorials, commentaries, or public addresses that referred to the professional role or identity of the pharmacist in either practice or education was retrieved and read in full. This study relied on published texts only, so research ethics board approval was not required. The data analysis was informed by the methods of Jager and Maier, in Methods of Critical Discourse Studies, 3rd edition.35 The analysis centered on an examination of the following ideas within the texts: In what ways are pharmacists and their professional identities described at different times over the past century? How did these descriptions and ideas influence different audiences (eg, pharmacists, students, educators and researchers)?

The texts in the archive were processed using an iterative analytic approach in which they were examined for truth statements about pharmacist identity, language used to describe identities, and subjects and objects made possible by the different identities. The texts were analyzed for irregularities until a stable description of various discourses emerged. The first author read each text in the archive and kept field notes. The notes included descriptions and/or discussions regarding professional roles or identities, quotes, subjects taught, faculty composition, and changes to degree titles and/or duration of training. During the data collection phase, the first author and the last author had regular meetings where they discussed patterns that were present in the analysis. The discussions aimed to distinguish the patterns that constituted discourses through identifying and refining truth statements, language, subjects, and objects produced by or linked to the discourses. The entire team was involved in review to ensure that the results were comprehensive and clear.

RESULTS

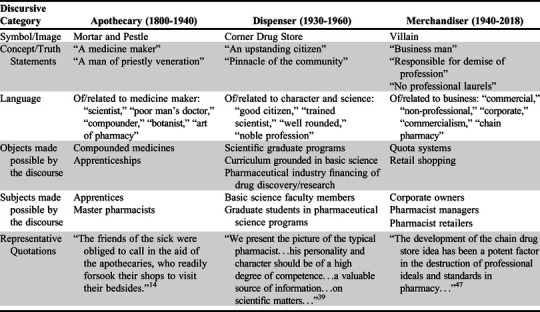

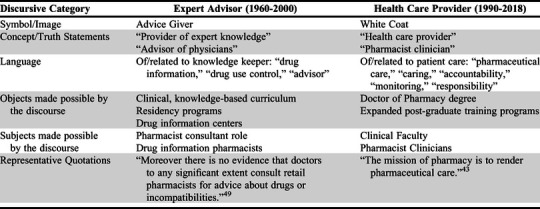

The documents retrieved for the analysis included predominantly commissioned education reports, editorials, commentaries, historical papers, position papers, and a small number of empirical studies. The date range of material included in the archive spans from 1937 to 2018. The archive contained more than 40 texts, encompassing over 500 pages. Five major identity discourses were identified: apothecary, dispenser, merchandiser, expert advisor, and health care provider. The features of each discourse, including the truth statements each embodies, the subjects and objects each enables, and the language each employ are described below and summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Importantly, although these discourses are distinct, they are not mutually exclusive. In fact, an unexpected finding of this study was that the identity discourses did not have clear shifts from one to another. Rather, elements of each identity were carried forward, but not in the sense that they were building on each other, but in ways that often were incompatible. We called this finding “discursive pile-ups.”

Table 1.

Apothecary, Druggist, and Merchandiser Discourses Within the Pharmacy Education Literature (1937-2018)

Table 2.

Expert Advisor and Health Care Provider Discourses Within the Pharmacy Education Literature (1937-2018)

The central truth statement regarding the apothecary identity construct is that of “medicine maker.” The apothecary was a person who combined the art and science of medicines to care for patients.15,17 Apothecaries practiced a mixture of medicine and pharmacy.15 The professional status of the apothecary was highly regarded, similar to that of the doctor or the priest.45 Apothecaries learned their trade by apprenticeship, often working with physicians. There were no formal institutions for pharmacy education so apprentices would work alongside a master, rendering seven years of service in exchange for learning the “mysteries of the trade.”15 These early days of pharmacy practice illustrate an important role for the profession within society, even in the absence of formal university training. Over time, as pharmacy education became more formalized, the discourse surrounding the apothecary carried a nostalgic tone, referencing the “good old days” and a desire to return to this identity construct, particularly because of the significant professional status afforded the apothecary and the rising threat that the profession would be corporatized.46 The language used to describe the apothecary in the archive is admirable: a man who was available to the community, who provided medical care to those from all socioeconomic backgrounds, particularly during times of great need, such as during the Great Plague.15,17 The subjects made possible by this discourse are that of apprentice and master pharmacist. The objects enabled are compounded medicines and apprenticeships. This identity has a legitimate social role, similar to that of medicine.

The central truth statement in the dispenser discourse is a dual one of “man of character” and “man of science.”39 There is a strong emphasis on the upstanding place of the dispenser in the community, with a prominent focus on the professional role outweighing commercial interests.39 The dispenser identity is associated with predominantly dispensing of medications, as well as some compounding of agents not commercially available, the provision of information related to public health, and as a source of scientific information to the layman due to accessibility. The community pharmacy is seen as a pinnacle of the community.40 The language used is heavily grounded in moral ethics and personality traits deemed to be associated with strong character. There is also a science component, and reference to the dispenser as a “scientist.”39 From this dispenser discourse, new subjects and objects are made possible. For example, this discourse enables an increase in basic science tenured faculty members, the development of scientific graduate programs, a curriculum grounded in the basic sciences, and a role for the pharmaceutical industry to finance drug discovery.41,42 In addition, the dispenser discourse is associated with filling prescriptions, some manufacturing of products, and the provision of health information. These activities were all legitimate ways in which pharmacists served patients and society.

The central truth statement in the merchandiser discourse is that this pharmacist identity is purely commercialized and, as such, undesirable.47 This discourse is burdened with the blame of the loss of status of the profession.47 The language used is aggressive and accusatory in nature. It is discussed predominantly in editorials, with a strong opinion to move away from identities associated with commercial pharmacy practice. There is concern over the role of the corporate employer and the conflict between serving the public and serving the corporation, with corporate culture trumping and dictating professional roles.48 A tension is experienced in this discourse in the archive as it is seen to be incompatible with the health care provider discourse,46,48 yet paradoxically the majority of current pharmacy graduates will practice in a commercial pharmacy environment. The subjects and objects made possible by the merchandiser discourse relate to business and profit. This discourse enables prescription volumes and quota systems to generate revenue. It also leads to the creation of pharmacy manager positions within the chain drug store setting. It enables a business-oriented curriculum and administrative courses. The corporate pharmacy institutions gain power with this discourse and the individual “staff” pharmacist experiences reduced professional autonomy. Throughout the archive, the merchant discourse is undervalued and associated with resentment, as it is felt to contribute to loss of professional status and power in pharmacy.47

The central truth statement of the expert advisor identity positions pharmacy as a knowledge system.42 Within this discourse, pharmacists take on a consultant or expert advisor role to physicians specifically. The patient is largely absent in the advisor discourse. The language used shifts to be more clinical in nature than in previous discourses; however, it lacks the patient as a potential advisee.

The clinical pharmacy movement is housed within this discourse, in which pharmacists can apply complex drug information and knowledge to improve health outcomes. The language is very encouraging and positions pharmacists as partners with physicians. A contradiction exists within this discourse in the archive in that physicians have not yet bought into this pharmacist expert identity.49 Also of note, this is the first time in the texts where the language explicitly suggests subordination in relation to the medical doctor. This discourse reinforces the view of the pharmacist as an advisor without decision-making authority. The subjects created by this discourse include pharmacist consultants and drug information pharmacists. The objects made possible are curricula with increased clinical and drug information content, as well as pharmacy residency programs, and drug information centers. This discourse emphasizes career paths related to dissemination of knowledge.

The central truth statement of the health care provider discourse is that pharmacists take accountability and responsibility for the outcomes of drug therapy in their patients.43 This discourse is housed in the pharmaceutical care movement. The language used in this discourse is assertive and authoritative. It seeks to reaffirm pharmacy as a legitimate health profession as long as pharmacists care for patients and take responsibility for drug outcomes.43 The subjects created by this discourse are predominantly clinicians and clinical faculty members. The objects made possible are the Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) degree, which is rooted in a clinically focused curriculum. It includes expanded training that incorporates physical assessment, immunizations, and increased experiential requirements. The PharmD degree comes with the title “Doctor” and adds an extra year of training, making the minimum time for completion of the degree six years. The health care provider discourse gives power to patient care. It seeks legitimacy through titles and patient care activities that mimic those of physicians. At the same time, it undervalues anything resembling the dispensing and merchant discourses by making them less legitimate.

DISCUSSION

This study identified five discourses in the pharmacy education literature related to the professional identities of pharmacists in North America over the last century. Currently, the health care provider discourse is dominant. It was born out of the desire of academic leaders to reprofessionalize pharmacy; hence, it is positioned in the archive as a “savior.”15,39,46,50 However, 50 years later the profession is still trying to actualize this identity in practice. Because of the paucity of research, it is unclear whether our educational institutions have been unsuccessful in socializing students to the health care provider identity, or if our practice settings undo this identity, or a combination of both. One potential explanation relates to our finding that there have been no clear discursive shifts from one identity construct to another in pharmacy education. Rather, this study exposed discursive “pile-ups” which occur when elements of previous identity discourses remain in the formal and/or hidden curriculum and impact learners’ abilities to fully form new collective identities. The different discourses are incompatible with each other, particularly the dispenser, merchant, and health care provider discourses. Educational settings value the health care provider discourse, while portraying the dispenser and merchant as less important and desirable. This creates confusion and tension for trainees and new pharmacy graduates because, in many cases, the health provider identity they aspire to during their education is in direct opposition to what they later experience in practice settings. Difficulty enacting the health care provider role may contribute to pharmacists’ dissatisfaction in the workplace and impact workforce retention, uptake of professional responsibilities, and future enrollment in pharmacy programs.10,22-23

Within contemporary education, the health care provider construct is given significant legitimacy and is seen by many as professional evolution. From a Foucauldian perspective, history is not progressive; hence, the health care provider identity is not a sign of progression but rather the professional identity currently associated with the most legitimacy in the social world. The health care provider identity most resembles the identity of medicine; hence, it is associated with more power than other identities. By challenging the assumption that the health care provider identity is an inevitable progression, one is able to make visible other ways of being for pharmacy and broadens the tent within which different individuals with different interests and strengths may be able to all claim allegiance to and legitimacy within the profession called pharmacy.

Pharmacy continues to renegotiate its place in modern society. On the one hand, pharmacy’s attempts to transform can be viewed as a strength, illustrating the profession’s robust adaptability and resilience in an ever-changing health care environment. On the other hand, it is a vulnerability in that it challenges the formation of a solid professional identity.7,8,24,27 A profession whose roles, responsibilities, and identities are constantly changing may be perceived by members of the public as unstable, unpredictable, and ultimately unreliable. In addition, socializing pharmacy students to a professional endpoint that is a moving target has challenged pharmacy educators for close to a century, resulting in curricular changes that are not designed with identity formation as a main goal.8 Pharmacy educators and leaders have been well intentioned in their attempts to transform the professional identity of pharmacists over time; however, they have been largely unsuccessful.10,12,22-24 Based on this study, a potential consequence of pharmacy’s ongoing quest for professional legitimacy is the accumulation of discursive identity pile-ups which inadvertently create conditions that make it challenging for pharmacy students to fully adopt the health care provider identity. As a result, it is plausible that students graduate with a fragile professional identity that can be easily shifted to another identity based on what is experienced in practice. This impacts the ability of the profession to fully enact the health care provider identity broadly, which further confuses the pharmacist’s role in modern society. This finding opens up new ways of conceptualizing pharmacist identity moving forward.

This work focused on a selection of pharmacy education literature specific to North America (but predominantly from the United States), where scholarship in pharmacy education has been historically dominant and influential. As such, the predominant identity discourses identified may be different outside of North America or with an archive that included a different journal as its base. In addition, the inclusion of a larger variety of artefacts in the archive, such as interviews with pharmacy leaders, as well as curriculum documents, organizational academic plans, and different journals, may have added further understanding to the discourses identified or introduced new ones.

This study highlights interesting opportunities for future research exploring how professional identity formation is embedded in curriculum, as well as how pharmacy students perceive their identity. A closer examination of the pharmaceutical care discourse is also warranted as it may shed light on the gaps between identity constructs in education and practice, and why the health care provider identity is considered the natural professional evolution for pharmacy.

CONCLUSION

This critical discourse analysis opens up the possibility that pharmacist identity constructs are not simple, self-evident, or progressive. When multiple discourses interplay, those using them need to understand their impact on student identity formation, specifically during the professional education years, and how it translates into their practice environment. This study helps pharmacy expose the identity constructs from the past that remain alive in the present and which can inform needed professional changes moving forward. It also serves as an example for other professions that seek to renegotiate professional identities and roles in the future.

REFERENCES

- 1.Irby D. Educating physicians for the future: Carnegie’s calls for reform. Med. Teach. 2011; 33:547-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruess R, Cruess S, Steinert Y. Introduction. In: Cruess R, Cruess S, Steinert Y, eds. Teaching Medical Professionalism: Supporting the Development of a Professional Identity. 2nd edition Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2016:1-4. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316178485.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad. Med. 2014; 89:1446-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myrlea M, Gupta T, Glass B. Professionalization in pharmacy education as a matter of identity. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79:142. doi: 10.5688/ajpe799142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mylrea MF, Gupta TS, Glass BD. Developing professional identity in undergraduate pharmacy students: a role for self-determination theory. Pharmacy. 2017;5:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooke M, Irby DM, O’Brien BC. Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawodu P, Rutter P. How do pharmacists construct, facilitate and consolidate their professional identity? Pharmacy. 2016;4(3):23. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy4030023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noble C, Coombes I, Shaw PN, Nissen LM, Clavarino A. Becoming a pharmacist: the role of curriculum in professional identity formation. Pharm. Pract. 2014; 12:380-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noble C, O’Brien M, Coombes I, Shaw PN, Nissen L, Clavarino A. Becoming a pharmacist: students’ perceptions of their curricular experience and professional identity formation. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2014; 6:327-339. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elvey R, Hassell K, Hall J. Who do you think you are? pharmacists’ perceptions of their professional identity. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013; 21:322-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson S, Turnbull J, Bainbridge L et al. Optimizing scopes of practice: new models for a new health care system. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Academy of Health Sciences; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kellar J. Who are we? The evolving professional role and identity of pharmacists in the 21st century. In: Babar ZUD, ed. Encyclopaedia of Pharmacy Practice and Clinical Pharmacy, Cambridge, MA; 2019:47-59. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monrouxe L. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Med. Educ. 2010;44(1):40-49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonnedecker G. Kremers and Urdang’s History of Pharmacy. 3rd ed Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Company; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buereki R. In search of excellence: the first century of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ . 1999;63(Fall Supplement):1-185. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helper C. The third wave in pharmaceutical education: the clinical movement. Am J Pharm Educ. 1987;51:369-385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muzzin L, Brown G, Hornosty R. Professional Ideology in Canadian Pharmacy. In Coburn D, D’Arcy C, Torrance GM, eds. Health and Canadian Society. 3rd ed Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press; 1993: 379-398. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Austin Z, Ensom M. Education of pharmacists in Canada. Am J Pharm Educ . 2008;752(6):128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sosabowski M, Gard P. Pharmacy education in the United Kingdom. Am J Pharm Educ . 2008;72(6):130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Association of Faculties of Pharmacy of Canada. Educational outcomes for first professional degree programs in pharmacy (entry-to-practice pharmacy programs) in Canada. 2010. and 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes 2013. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenthal M, Austin Z, Tsuyuki R. Are pharmacists the ultimate barrier to practice change? Can Pharm J. 2010; 143:37-42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frankel GEC, Austin Z. Responsibility and confidence: identifying barriers to advanced pharmacy practice. CPJ. 2013;14(3):155-161. Doi: 10.1177/1715163513487309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biggs C, Hall J, Charrois TL. Professional abstinence: what does it mean for pharmacists? CPJ . 2019;152(3):148-150. DOI: 10.1177/1715163519840055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morison S, O’Boyle A. Developing professional identity: a study of the perceptions of first year nursing, medical, dental and pharmacy students. In Callara L.R, ed. Nursing Education Challenges in the 21st Century. New York: Nova Science; 2007: 195-220 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kritikos V, Watt HMG, Krass I, Sainsburry EJ, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ. Pharmacy students’ perceptions of their profession relative to other health care professions. Int J Pharm Pract. 2003; 11:121-129. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gregory P, Austin Z. Pharmacists’ lack of professionhood: Professional identity formation and its implications for practice [published online ahead of print May 16, 2019]. CPJ. doi: 10.1177/1715163519846534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Hodges BD, Martimianakis MA, McNaughton N, Whitehead C. Medical education…meet Michel Foucault. Med. Educ. 2014; 48:563-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan K, Bissell P, Morgall Traulsen J. The work of Michel Foucault: relevance to pharmacy practice. Int J Pharm Pract. 2004; 12:43-52. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutting G. Foucault: A Very Short Introduction. 1st ed New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Farrell C. Michel Foucault. SAGE publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kendall G, Wickham G. Using Foucault’s Methods. London, UK: SAGE; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hodges BD, Kuper A, Reeves S. Discourse analysis. BMJ. 2008; 337:570-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuper A, Whitehead C, Hodges BD. Looking back to move forward: using history, discourse and text in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 73. Med. Teach. 2013; 35:e849-e860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wodak R, Meyer M. Methods of Critical Discourse Studies. 3rd ed London, UK: SAGE; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haddara W, Lingard L. Are we all on the same page? a discourse analysis of interprofessional collaboration. Acad. Med. 2013; 88:1509-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fairclough N. Critical discourse analysis and the marketization of public discourse: the universities. Discourse Soc . 1993;4:133-168. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foucault M. 1969. The Archaeology of Knowledge. Trans A. Sheridan Smith M. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charters WW, Lemon AB, Monell LM. Basic Material for a Pharmaceutical Curriculum. 1st ed New York: Mc-Graw-Hill; 1927. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elliott EC. Findings and Recommendations of the Pharmaceutical Survey 1948.1st ed Washington, DC: American Council on Education; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elliott EC. The General Report of the Pharmaceutical Survey 1946-49. 1st ed Washington, DC: American Council on Education; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 42.The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Pharmacists for the Future: The Report of the Study Commission on Pharmacy. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Health Administration Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Commission to Implement Change in Pharmaceutical Education. Entry-level education in pharmacy: a commitment to change [A Position Paper]. Am J Pharm Educ. 1993;57:366-374. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jager S, Maier F. Analysing discourses and dispositives: a Foucauldian approach to theory and methodology. In: Wodak R, Meyer M, eds. Methods of Critical Discourse Studies. 3rd ed London, UK: SAGE; 2016:109-136. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tainter ML. Pharmacy a noble profession. Am J Pharm Educ. 1952;16:5-10. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caldwell HW. Address of president Harmon W. Caldwell – University of Georgia. Am J Pharm Educ. 1937;1: 25-37. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson RC. Address of the president of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy at Dallas, Texas, August 24, 1936. Am J Pharm Educ. 1937;1:16-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen JL, Nahata MC, Roche VF, et al. Pharmaceutical care in the 21st century: from pockets of excellence to standard of care: report of the 2003-04 Argus Commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68:S9. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ladinsky J. Professionalism in pharmacy education in the contemporary period. Am J Pharm Educ. 1974;38:679-690. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romanelli F. Flexner, educational reform and pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(2):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]