Abstract

Context.

Racial and ethnic disparities in end-of-life care are well documented among adults with advanced cancer.

Objectives.

To examine the extent to which communication and care differ by race and ethnicity among children with advanced cancer.

Methods.

We conducted a prospective cohort study at nine pediatric cancer centers enrolling 95 parents (42% racial/ethnic minorities) of children with poor prognosis cancer (relapsed/refractory high-risk neuroblastoma). Parents were surveyed about whether prognosis was discussed; likelihood of cure; intent of current treatment; and primary goal of care. Medical records were used to identify high-intensity medical care since the most recent recurrence. Logistic regression evaluated differences between white non-Hispanic and minority (black, Hispanic, and Asian/other race) parents.

Results.

About 26% of parents recognized the child’s low likelihood of cure. Minority parents were less likely to recognize the poor prognosis (odds ratio [OR] = 0.19; 95% CI = 0.06−0.63; P = 0.006) and the fact that current treatment was unlikely to offer cure (OR = 0.07; 95% CI = 0.02−0.27; P <0.0001). Children of minority parents were more likely to experience high-intensity medical care (OR = 3.01; 95% CI = 1.29−7.02; P = 0.01). After adjustment for understanding of prognosis, race/ethnicity was no longer associated with high-intensity medical care (adjusted odds ratio = 2.14; 95% CI = 0.84−5.46; P = 0.11), although power to detect an association was limited.

Conclusion.

Parental understanding of prognosis is limited across racial and ethnic groups; racial and ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected. Perhaps as a result, minority children experience higher rates of high-intensity medical care. Work to improve prognostic understanding should include focused work to meet needs of minority populations.

Keywords: End-of-life, pediatric, cancer, disparities, communication, prognosis

Introduction

Racial disparities in end-of-life care for adults with cancer are well described, with lower rates of advance care planning and hospice utilization among racial and ethnic minorities and higher rates of late-life hospitalizations and care in the intensive care unit.1−12 In part, higher use of intensive measures among minorities reflects patient preferences for care; adult patients of minority race/ethnicity are more likely than white patients to want life-prolonging measures at the end of life.2,3,8 However, existing evidence also suggests that minority patients experience suboptimal communication about prognosis and advance care planning, which can in turn influence choices for care. For example, physicians are less likely to discuss prognosis with minority patients with advanced cancer as compared with white patients.13 When these conversations do take place, physicians are more likely to use euphemisms or expressions of optimism when talking with minorities.13 Perhaps as a result, prior studies have identified disparities in understanding of prognosis, with minority patients more likely to hold overly optimistic beliefs about outcomes.14−16 All these factors have potential to influence care at the end of life.

The extent to which previously described disparities in communication and care apply to children with advanced cancer is not well understood. The limited existing work has identified17 cultural and language barriers to optimal palliative care for Spanish-speaking and Mexican immigrant families18,19 and higher rates of inpatient deaths among children with cancer who are racial or ethnic minorities relative to whites.20−22 However, important gaps in knowledge remain, including the underpinnings of disparities.23,24 Efforts to improve health equity for children at the end of life require a deeper understanding of the nature and determinants of disparities.

We sought to examine prognosis communication as one potential source of end-of-life care disparities among children with advanced cancer. We prospectively enrolled a diverse cohort of parents of children with a single poor prognosis cancer (relapsed or refractory high-risk neuroblastoma), as a model that offers insight into care of children with other life-threatening conditions. More than half of children with newly diagnosed high-risk neuroblastoma will either never achieve remission or relapse after treatment.25 Five-year overall survival is estimated at 4% after recurrence,26−28 and only slightly higher in refractory disease.27,28 Despite poor prognoses, children with relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma have numerous options for care, including a range of cancer-directed therapies and noncancer-directed treatment focused on symptom management. Relapsed/refractory high-risk neuroblastoma therefore presents a model for parental decision making for children with advanced cancer.

Initial findings from this study, focused on understanding of prognosis among participating parents, have been reported previously.29 For this study, we examined racial and ethnic differences in factors relevant to parental decision making for advanced pediatric cancer.

Patients and Methods

We surveyed parents of children with relapsed/refractory high-risk neuroblastoma receiving care at nine sites (Table 1) from September 2013 to July 2018.29 One parent per child was eligible to participate any time after the child’s relapse/refractory diagnosis if the parent was English speaking or Spanish speaking and older than 18 years, and if the child was younger than 18 years. Parents were approached in person for an informed consent discussion and given a study letter. To acknowledge parents’ time and effort, a $50 gift card was offered on baseline survey completion. Medical records dating from diagnosis and consenting parents’ contact information were forwarded to Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Boston Children’s Hospital via secure Research Electronic Data Capture database.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Parents and Children, Including Prior Care and Treatment (N = 95)

| Full Cohort (% Unless Otherwise Specified) |

White |

Minority |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Characteristics | N = 95 | N = 55 | N = 40 | P |

| Parent gender | 0.42 | |||

| Female | 81 | 84 | 77 | |

| Male | 19 | 16 | 23 | |

| Parent education | 0.65 | |||

| Higher than high school graduate | 82 | 84 | 80 | |

| High school graduate or lesser | 18 | 16 | 20 | |

| Parent race/ethnicity | N/A | |||

| White | 58 | 100 | 0 | |

| Black | 8 | 0 | 20 | |

| Hispanic | 23 | 0 | 55 | |

| Other | 11 | 0 | 25 | |

| Study site | 0.09 | |||

| Boston Children’s Hospital/Dana-Farber Cancer Institute | 22 | 25 | 18 | |

| Children’s Hospital Los Angeles | 18 | 16 | 20 | |

| Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia | 20 | 24 | 15 | |

| Columbia University Medical Center | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| Cook Children’s | 7 | 5 | 10 | |

| Seattle Children’s Research Institute | 6 | 7 | 5 | |

| St Jude Children’s Research Center | 6 | 7 | 5 | |

| Stanford/Packard Children’s Hospital | 9 | 2 | 20 | |

| University of Chicago | 7 | 11 | 3 | |

| Religious coping | ||||

| Greater use of religious coping | 49 | 35 | 68 | 0.002 |

| Lesser use of religious coping | 51 | 65 | 33 | |

| Child Characteristics | ||||

| Child gender | 0.67 | |||

| Female | 40 | 42 | 38 | |

| Male | 60 | 58 | 63 | |

| Child age at time of parent enrollment (yrs) | Mean 6.4; median 6 (SD 3.1) | Mean 6.7; median 7 (SD 2.7) | Mean 6.1; median 5 (SD 3.6) | 0.35 |

| Care and Treatment Characteristics | 0.02 | |||

| Neuroblastoma status | ||||

| Recurrent | 77 | 85 | 65 | |

| Refractory to initial therapy | 23 | 15 | 35 | |

| Number of prior chemotherapeutic regimens | Mean 3.5; median 3 (SD 2.2) | Mean 3.6; median 4 (SD 2.5) | Mean 3.3; median 3 (SD 1.8) | 0.37 |

N/A = not available.

P-values indicate Chi-squared tests comparing proportions who are white (white non-Hispanic) Vs. minority (nonwhite or Hispanic); t-tests were used for continuous variables.

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Boston Children’s Hospital research staff administered questionnaires in English or Spanish to consenting parents; one site (Cook Children’s Hospital) administered questionnaires themselves. Questionnaires were administered either verbally (by phone or in person) or as paper or electronic versions. Details of survey development and medical record review have been described previously.29

The questionnaire asked parents to reflect on the most recent decision about the child’s care and treatment, including cancer-directed treatment and/or care focused on symptoms and quality of life. Medical record reviews focused on care received. Variables of interest are detailed later.

Communication About Prognosis

Communication about prognosis was assessed by asking parents, Has your child’s oncologist discussed your child’s likelihood of cure with you? (yes or no). We also reviewed medical records for any documented discussions about prognosis since the most recent recurrence/diagnosis of refractory disease.

Parents’ Understanding of Prognosis

Parents’ understanding of prognosis was assessed by asking, How likely do you think it is that your child will be cured of neuroblastoma?30−32 Response categories were extremely likely (>90% chance of cure), very likely (75%−90%), moderately likely (50%−74%), somewhat likely (25%−49%), unlikely (10%−24%), very unlikely (<10%), or no chance of cure;30−32 understanding of prognosis was defined as parental recognition of chances of cure of <25%.

Parents’ Understanding of Treatment Intent

Parents’ understanding of treatment intent was assessed by asking parents who reported that their child was currently receiving cancer-directed therapy (N = 87) to identify how likely it is that cure of my child’s neuroblastoma would result from the child’s current treatment (not at all likely, a little likely, somewhat likely, very likely, extremely likely);15 understanding of treatment intent was defined as a parent report that cure was either not at all likely or a little likely to result from the current treatment. As a sensitivity analysis, we classified responses of anything other than extremely or very likely as understanding of treatment intent.15

Parents’ Goals of Care

Parents were asked, Parents have many goals of care for their children with neuroblastoma. What are your goals for your child’s care right now? Parents were able to choose all applicable goals, with response categories of to cure my child’s cancer, to help my child live as long as possible, and to relieve pain and discomfort, and improve quality of life, as much as possible. Parents were then asked, if they had to choose, what their single most important goal would be, with identical response categories.31,33

High-Intensity Medical Care

Medical records were used to identify markers of high-intensity medical care between the most recent recurrence and date of survey completion, including care in the intensive care unit; mechanical ventilation; blood pressure support; treatment for bacteremia; frequent inpatient, emergency room, or outpatient visits (more than five days/month); or highly myelosuppressive therapy requiring stem cell infusion.

Parent Factors

Parent factors included self-reported race/ethnicity, gender, age, education, and marital status. Religious coping was identified using the Brief R-COPE, a four-item instrument used to measure the extent to which coping is religious (e.g., I’ve been trying to see how God might be trying to strengthen me in this situation, with response categories of not at all, somewhat, quite a bit, and a great deal). Scores were summed and dichotomized at the median to represent greater and lesser use of religious coping, consistent with previous methods.34,35

Child Factors

Child factors included medical record-derived dates of birth, diagnosis, and recurrence/refractory diagnosis.

Institutional review boards of all participating sites approved the study.

Statistical Methods

Summary statistics were used to describe parent and child characteristics. Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables were used to examine differences in characteristics between white and minority parents, with minority parents defined as any racial or ethnic group other than white non-Hispanic. Proportions of parents with each of our primary variables of interest (communication about prognosis, prognostic understanding, understanding of treatment intent, goals of care, and receipt of medically intensive care) were examined by racial/ethnic group (white non-Hispanic, black, Hispanic, and Asian/other race), showing all racial/ethnic categories descriptively given potential differences by racial/ethnic group, with Chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact test used to evaluate differences in proportions.

Logistic regression analyses were used to examine relationships between race/ethnicity and primary variables of interest. For all logistic regression analyses, we analyzed race/ethnicity as white vs. minority, given the small number of parents in each racial/ethnic group and small overall sample size. In addition to unadjusted logistic regression, we adjusted analyses for relapsed vs. refractory disease and for use of religious coping, proportions of which differed by race/ethnicity, and performed exploratory analyses adjusting for parental education, which did not differ by race/ethnicity but was considered to be a potentially relevant covariate for issues of medical communication. Results for adjustment for education were similar to other findings and are not presented here. Degree of association was summarized as odds ratios (ORs), adjusted odds ratios (aORs), and corresponding 95% CIs.

Results

Of 152 parents approached for the study, 117 (77%) agreed to participate; 95 parents (81% of consenting parents and 63% of those approached) completed questionnaires, eight children of enrolled parents died before parental survey completion, two parents withdrew consent, and 12 never completed the survey. Participants did not differ significantly from nonparticipants by race/ethnicity (P = 0.55) or child gender (P = 0.59).

Most participants were mothers (Table 1). Fifty-eight percent were white, 8% black, 23% Hispanic, and 11% Asian or other race/ethnicity. Median child age was six years. Parent gender and education did not differ significantly by parent race/ethnicity (P = 0.42 and 0.65, respectively). Minority parents were more likely to report greater use of religious coping than white parents (P = 0.002), and their children were more likely to have refractory disease than children of white parents (P = 0.02). Study sites had nonstatistically significant differences in racial/ethnic balance (P = 0.09).

Most parents (82%; 77 of 94) reported that the oncologist had discussed prognosis with them at some point in time since diagnosis, including 84% of white parents (46 of 55), 63% of black parents (5 of 8), 90% of Hispanic parents (19 of 21), and 70% of Asian/other race parents (7 of 10), with no difference by parent race/ethnicity (P = 0.25). The proportion of parents recalling discussions about prognosis was similar for minority vs. white parents in unadjusted logistic regression (OR = 0.76; 95% CI = 0.26−2.18; P = 0.61) and when adjusted for refractory disease (aOR = 0.82; 95% CI = 0.27−2.43; P = 0.71) and for religious coping (aOR = 0.59; 95% CI = 0.19−1.85; P = 0.37). Documented discussions about prognosis since the most recent recurrence, present in 33% of records (31 of 95), also did not differ by race/ethnicity (P = 0.23 across all racial/ethnic categories; OR for minority vs. white parents = 0.99; 95% CI = 0.42−2.36; when adjusted for refractory disease: aOR = 1.13; 95% CI = 0.46−2.77; P = 0.80; when adjusted for religious coping: aOR = 0.91; 95% CI = 0.36−2.27; P = 0.83).

Overall, only 26% (24 of 91) of parents recognized the child’s poor prognosis, defined as a chance of cure of less than 25%. Understanding of prognosis differed by parent race and ethnicity (Fig. 1), with 38% of white parents recognizing the child’s poor prognosis (20 of 53), relative to 14% of black parents (one of seven), 5% of Hispanic parents (1 of 22), and 22% of Asian/other race parents (two of nine, P = 0.02, Chi-squared test). Findings were similar for minority relative to white parents in logistic regression in both unadjusted analyses (OR = 0.19; 95% CI = 0.06−0.63; P = 0.006) and analyses adjusted for refractory disease (aOR = 0.19; 95% CI = 0.06−0.65; P = 0.008) and religious coping (aOR = 0.21; 95% CI = 0.06−0.72; P = 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Parent recognition that the child’s chances of cure were less than 25%, stratified by parent race/ethnicity. P-value calculated using Chi-squared test.

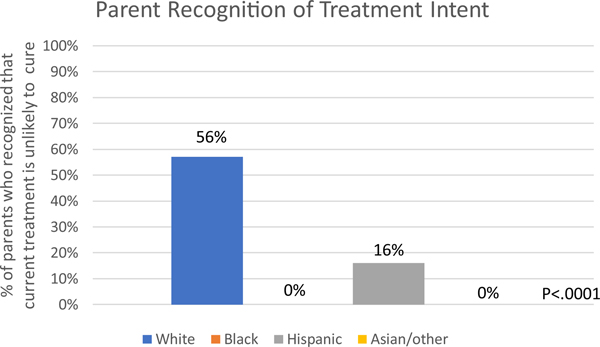

Of 87 parents whose children were currently receiving cancer-directed therapy, 38% (33 of 87) recognized that the child’s current treatment was unlikely to offer cure. Among white parents, 57% recognized that cure was unlikely (30 of 53); 16% of Hispanic parents recognized this (3 of 19), and no black or Asian/other race parents did (P = 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test; Fig. 2). Findings were similar for minority vs. white parents in unadjusted logistic regression (OR = 0.07; 95% CI = 0.02−0.27; P < 0.0001) and analyses adjusted for refractory neuroblastoma (aOR = 0.08; 95% CI = 0.02−0.30; P = 0.0002) and religious coping (aOR = 0.08; 95% CI = 0.02−0.30; P = 0.0002). A sensitivity analysis considering responses of anything less than very likely to be accurate had similar results (P = 0.03, Chisquared test; unadjusted OR = 0.26; 95% CI = 0.10−0.65; P = 0.004; adjusted for refractory disease: aOR = 0.25; 95% CI = 0.09−0.64; P = 0.004; adjusted for religious coping: aOR = 0.30; 95% CI = 0.11−0.78; P = 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Parent recognition that the child’s current treatment was no more than a little likely to offer cure, stratified by parent race/ethnicity. P-value calculated using Fisher’s exact test.

Parents’ goals of care did not differ by race/ethnicity (P = 0.39), with 19% (18 of 94) of parents reporting that their primary goal of care at present was improving quality of life. This included 24% of white parents (13 of 54), 25% of black parents (two of eight), 9% of Hispanic parents (2 of 22), and 10% of Asian/other race parents (1 of 10). Prioritization of quality of life was also no different among minority relative to white parents in unadjusted (OR = 0.45; 95% CI = 0.15−1.39; P = 0.17) and adjusted logistic regression (adjusted for refractory disease: aOR = 0.48; 95% CI = 0.15−1.51; P = 0.21; adjusted for religious coping: aOR = 0.53; 95% CI = 0.16−1.73; P = 0.30).

Nearly half of children (47%; 49 of 95) received at least one form of high-intensity medical care since the last recurrence. About 38% of children of white parents received medically intensive care (21 of 55), compared with 63% of children of black parents (five of eight), 64% children of Hispanic parents (14 of 22), and 70% children of Asian/other race parents (7 of 10; P = 0.08). After logistic regression using combined racial/ethnic categories, children of minority parents were more likely to receive medically intensive measures than children of white parents (OR = 3.01; 95% CI = 1.29−7.02; P = 0.01), with slight attenuation after adjustment for refractory disease (aOR = 2.47; 95% CI = 1.02−5.97; P = 0.046) and religious coping (aOR = 2.57; 95% CI = 1.06−6.26; P = 0.04). After adjustment for understanding of prognosis, race/ethnicity was no longer associated with receipt of highintensity medical care (aOR = 2.14; 95% CI = 0.84−5.46; P = 0.11). We also tested for effect modification by including an interaction term between race/ethnicity and prognostic understanding in the model. The interaction term was not statistically significant (OR = 0.75 for nonwhite patients with prognostic understanding; 95% CI = 0.06−8.81; P = 0.82), suggesting that race does not modify the effect of prognostic understanding on treatment intensity.

Discussion

Previous work among adult patients with cancer has identified pervasive disparities in end-of-life care.1−12 Work in pediatric oncology, and across pediatrics, has been more limited, with a handful of studies raising concern that minority children and those of low socioeconomic status have inferior end-of-life experiences.17−22 Our study adds to this work by examining communication and care in a prospective cohort of parents of children with advanced cancer. Parent reports of prognosis communication processes were similar across racial and ethnic groups, whereas parents of minority race/ethnicity were less likely to recognize the child’s poor prognosis and less likely to understand that treatment was unlikely to offer cure. Perhaps as a result, use of high-intensity medical care was also higher among children of minority parents.

Understanding of prognosis has been identified as a prerequisite for informed decision making about advanced cancer; parents who recognize that a child with relapsed or refractory high-risk neuroblastoma is unlikely to be cured are more likely to choose care focused on quality of life over life-extending care.29 Prior work in adults from the 1990s found that desire for prognostic information varied by racial and ethnic group, with less interest in prognostic information among adult minority patients.36 However, in our own prior work among parents of children with newly diagnosed cancer, parents’ wishes for information did not vary by race or ethnicity. Instead, desire for prognostic information was nearly universal,37 perhaps reflecting more modern norms or the special obligation parents feel to be well informed about the health of their children. That study also found that oncologists’ perceptions of what parents wanted to know, as well as oncologists’ beliefs about parents’ capacity to understand medical information, varied significantly by race and ethnicity.37 Although that study and the present study found no difference in parent reports of prognostic communication, the difference in oncologist attitudes about communication raises the question as to whether other unmeasured aspects of communication may have differed and underpinned the disparity in knowledge that we found.

Parent understanding of treatment intent similarly differed by racial and ethnic groups, with minority parents less likely than white parents to recognize that current treatment offered limited prospect of cure. Misperceptions about the goals of treatment are common among adults with advanced cancer.15 Our findings raise the concern that treatment decision making for children with advanced cancer often occurs in the absence of full parental understanding of what treatment can offer.

Although we also found that goals of care were not statistically different among racial and ethnic minority parents, their children were more likely to experience high-intensity medical care. This again reflects findings among minority adults, who are more likely to receive late-life care in the hospital and intensive care unit, for example.4 The underpinnings of these disparities in adults are thought to be multifactorial. Although minority adult patients are more likely to wish for life-prolonging care at the end of life,2,3,8 effective communication and collaboration around advance care planning also seem to be lacking more often in minorities.38,39 Lack of prognostic understanding is a likely mechanism in our population as well; race was no longer statistically associated with receipt of high-intensity medical care once we adjusted for understanding of prognosis, although given our small sample size, our ability to detect associations was limited.

Because we focused on a single rare condition, our sample size was small, limiting our ability to detect small effects or to adjust for multiple variables. Black parents were represented in relatively low numbers, and although we displayed descriptive data by racial/ethnic category, the overall sample size precluded examination of effects within each racial/ethnic group. Instead, logistic regression examined effects in minority parents combined, although religious, cultural, and personal considerations likely varied widely in this diverse group. However, the focus on a single rare condition offered opportunity to ensure that other differences in cancer type, therapeutic options, and prognosis were not driving our findings. Future work should explore the underpinnings of differences identified with attention to unique needs within subpopulations of minority groups.

In addition, although we identified differences in understanding of prognosis and treatment intent, we still do not know the reasons for these differences. Although we speculate based on previous work that the nature of oncologists’ prognostic communication may differ by racial and ethnic groups, there may also be important differences in processing of information and the ways in which different parents chose to respond to our questions. Some parents, for example, may have been expressing hopes rather than expectations about outcomes. However, the finding of higher medical intensity of care among minority children suggests that the identified differences in perspectives about prognosis are clinically relevant and influence decision making.

Even among adult patients, for whom prognosis communication has been studied more extensively and refined interventions have been developed, optimal ways of communicating information about prognosis and treatment intent have not been defined. The best ways to meet needs of minority populations in particular require further study. However, some basic strategies are likely to be helpful to all parents. We recommend making sure prognosis and treatment intent are addressed at critical junctures such as recurrence and new treatment decisions. Clinicians can also check understanding by asking parents what they know about their child’s prognosis and revisit this topic over time, so that information can be absorbed outside the crisis of bad news and urgent decisions. These strategies may be helpful to all parents, regardless of racial or ethnic background.

Key Message.

In this multicenter prospective study of 95 parents of children with very poor prognosis childhood cancer, minority parents were less likely than white parents to recognize their child’s poor prognosis and more likely to receive intensive measures.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many parents who participated in this study.

Funding: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and Friends for Life Neuroblastoma Research Fund.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Smith AK, Earle CC, McCarthy EP. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life care in fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness, and treatment preferences. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4131–4137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, Gallagher PM, Fisher ES. Racial and ethnic differences in preferences for end-of-life treatment. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnato AE, Chang CC, Saynina O, Garber AM. Influence of race on inpatient treatment intensity at the end of life. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:338–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Barriers to hospice care among older patients dying with lung and colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Ngo-Metzger Q, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Hospice use among Medicare managed care and fee-for-service patients dying with cancer. JAMA 2003;289:2238–2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tanis D, Tulsky JA. Racial differences in hospice revocation to pursue aggressive care. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mack JW, Paulk ME, Viswanath K, Prigerson HG. Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1533–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Paulk E, et al. Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5559–5564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng NT, Mukamel DB, Caprio T, Cai S, Temkin-Greener H. Racial disparities in in-hospital death and hospice use among nursing home residents at the end of life. Med Care 2011;49:992–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lepore MJ, Miller SC, Gozalo P. Hospice use among urban Black and White U.S. nursing home decedents in 2006. Gerontologist 2011;51:251–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welch L, Teno JM, Mor V. End-of-life care in black and white: race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1145–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingersoll LT, Alexander SC, Priest J, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in prognosis communication during initial inpatient palliative care consultations among people with advanced cancer. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:1098–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G, et al. Determinants of patient-oncologist prognostic discordance in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1421–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1616–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enzinger AC, Zhang B, Schrag D, Prigerson HG Outcomes of prognostic disclosure: associations with prognostic understanding, distress, and relationship with physician among patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33:3809–3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilowite MF, Al-Sayegh H, Ma C, et al. The relationship between household income and patient-reported symptom distress and quality of life in children with advanced cancer: a report from the PediQUEST study. Cancer 2018;124:3934–3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen H. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Contro N, Davies B, Larson J, Sourkes B. Away from home: experiences of Mexican American families in pediatric palliative care. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2010;6:185–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cawkwell PB, Gardner SL, Weitzman M. Persistent racial and ethnic differences in location of death for children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62:1403–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston EE, Alvarez E, Saynina O, et al. Disparities in the intensity of end-of-life care for children with cancer. Pediatrics 2017;140:e20170671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston EE, Bogetz J, Saynina O, et al. Disparities in inpatient intensity of end-of-life care for complex chronic conditions. Pediatrics 2019;143:e20182228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linton JM, Feudtner C. What accounts for differences or disparities in pediatric palliative and end-of-life care? A systematic review focusing on possible multilevel mechanisms. Pediatrics 2008;122:574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beaune L, Morinis J, Rapoport A, et al. Paediatric palliative care and the social determinants of health: mitigating the impact of urban poverty on children with life-limiting illnesses. Paediatr Child Health 2013;18:181–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ries L, Percy CL, Bunin GR. Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975–1995. Bethesda, MD: NCI SEER Program, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.London WB, Castel V, Monclair T, et al. Clinical and biologic features predictive of survival after relapse of neuroblastoma: a report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group project. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3286–3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreno L, Rubie H, Varo A, et al. Outcome of children with relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma: a meta-analysis of ITCC/SIOPEN European phase II clinical trials. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garaventa A, Parodi S, De Bernardi B, et al. Outcome of children with neuroblastoma after progression or relapse. A retrospective study of the Italian neuroblastoma registry. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:2835–2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mack JW, Cronin AM, Uno H, et al. Unrealistic parental expectations for cure in poor-prognosis childhood cancer. Cancer 2020;126:416–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SJ, Fairclough D, Antin JH, Weeks JC. Discrepancies between patient and physician estimates for the success of stem cell transplantation. JAMA 2001;285:1034–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA 1998;279:1709–1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mack JW, Cook EF, Wolfe J, et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children with cancer: parental optimism and the parent-physician interaction. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1357–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med 2000;342:326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:445–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA 2009;301:1140–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blackhall LJ, Murphy ST, Frank G, Michel V, Azen S. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA 1995;274:820–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ilowite MF, Cronin AM, Kang TI, Mack JW. Disparities in prognosis communication among parents of children with cancer: the impact of race and ethnicity. Cancer 2017;123:3995–4003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanders JJ, Robinson MT, Block SD. Factors impacting advance care planning among African Americans: results of a systematic integrated review. J Palliat Med 2016;19:202–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanders J, Johnson K, Cannady K, et al. From barriers to assets: rethinking factors impacting advance care planning for African Americans. Palliat Support Care Cancer 2019;17:306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]