Abstract

Aims

How general practitioners (GPs) manage dyskalaemia is currently unknown. This study aimed at describing GP practices regarding hypokalaemia or hyperkalaemia diagnosis and management in their outpatients.

Methods and results

A telephone survey was conducted among French GPs with a 20‐item questionnaire (16 closed‐ended questions and 12 open‐ended questions) regarding their usual management of hypokalaemia or hyperkalaemia patients, both broadly and more specifically in patients with heart failure and/or chronic kidney disease and/or in patients treated with angiotensin‐converting enzyme/angiotensin receptor blockers or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. We aimed to interview 500 GPs spread geographically throughout France. This descriptive survey results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (if normally distributed or as median and inter‐quartile range if the distribution was skewed). Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and proportions (%). A total of 500 GPs participated in the study. Dyskalaemia thresholds (for diagnosis and intervention) and management patterns were highly heterogeneous. The mean ± SD (range) potassium level leading to ‘intervene’ was 5.32 ± 0.34 mmol/L (4.5–6.5) for hyperkalaemia and 3.23 ± 0.34 mmol/L (2.0–6.5) for hypokalaemia. Potassium levels leading to refer the patient to the emergency department (ED) were 6.14 ± 0.55 (4.5–10) and 2.69 ± 0.42 mmol/L (1–4), respectively. Potassium binders (51–65%) or potassium supplements (67–74%) were frequently used to manage hyperkalaemia or hypokalaemia. GPs uncommonly referred their dyskalaemic patients to cardiologists or nephrologists (or to the emergency department, if the latter was deemed necessary owing to the severity of the dyskalaemia). We identified an association between the close vicinity of GP office from an ED and ‘referring a heart failure patient’ (19.2% with ED vs. 8.6% without ED) and referring a heart failure and chronic kidney disease patient on mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (16.7% with ED vs. 9.3% without ED). Although the majority (67%) of GPs had an electrocardiogram on hand, it was rarely used (14%) in dyskalaemic patients. Subgroup analyses considering gender, age of the participating GPs, and high‐income/low‐income regions did not identify specific patterns regarding the multidimensional aspect of dyskalaemia management.

Conclusions

Owing to the considerable heterogeneity of French GP practices toward dyskalaemia diagnosis and management approaches, there is a likely need to standardize (potentially enabled by therapeutic algorithms) practices.

Keywords: General practitioners, Hyperkalaemia, Hypokalaemia, Heart failure, Chronic kidney disease/ mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist

Introduction

Hypokalaemia and hyperkalaemia are frequent electrolyte disorders consistently found to be associated with increased mortality across various patient populations. Observational data indeed report a U‐shaped association between serum potassium levels and mortality, with both hypokalaemia and hyperkalaemia being associated with worse outcomes. Dyskalaemia is particularly common among patients with cardiovascular diseases [heart failure (HF), 1 arterial hypertension, and coronary artery disease 2 ], notably in association with older age and co‐morbidities such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) and diabetes, and is related to renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASis), in particular mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) (hyperkalaemia) and non‐potassium‐sparing diuretic use (hypokalaemia). 3

The lowest risk of all‐cause mortality across studies is observed for blood potassium levels from 4 to 4.5 mEq. 4 There is, however, no actual international consensual agreement regarding a cut‐off value for defining hyperkalaemia or hypokalaemia. Potassium thresholds indeed differ between the various guidelines. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Hyperkalaemia is, however, frequently defined by serum levels ≥ 5 or 5.5 mmol/L, 9 , 10 while the European Resuscitation Council defines hyperkalaemia as a plasma level > 5.5 mmol/L. 7 , 8 Hypokalaemia is generally defined by a serum level ≤ 3.5 or even 4 mmol/L. 10 In case of severe hyperkalaemia > 6 or 6.5 or hypokalaemia < 3 mmol/L, initiation of emergency care is recommended. 7 , 8 , 10

While the management of acute or emergent dyskalaemia is reasonably well established, 9 the optimal management of moderate hyperkalaemia or hypokalaemia or with progressive onset is conversely currently undetermined in outpatients frequently managed by general practitioners (GPs).

In light of the latter, this study aimed to describe French GP practices with regard to dyskalaemia management in their outpatients, with special emphasis on HF and/or CKD patients, two frequently associated conditions.

Methods

Study design and patient population

A telephone survey, the Management of HyperKALaemia and Hypokalaemia by General Practitioners Study (‘KAL GP’ Study), was conducted among French GPs. To obtain a nationally representative sample, the study aimed to interview 500 GPs spread geographically throughout France. We performed a random draw in the directories of each French department. In order to obtain the targeted sample size, a constant proportion of GPs, representative of the number of GPs in each region, was calculated. Medical Associations, the Council of the Order of Physicians, Regional Unions in Healthcare, physician groups on social networks, and previously interviewed GPs were asked to disseminate a proposal to participate in the Kal GP Survey. A total of 618 calls were made in order to obtain the expected 500 responses. The 118 doctors who did not respond did not express a refusal but simply did not answer the message left (most often at the secretariat).

All participants were GPs who had general practice as their main activity, excluding physicians practicing exclusively ‘alternative medicine’, such as osteopathy, acupuncture, and homoeopathy; these physicians represent a small proportion of French doctors.

The telephone survey was conducted by a single physician (L. A. V.) by questionnaire. There were no missing data.

This questionnaire was previously validated after testing on a GP sample (composed of 10 GP residents and GPs from the University's Department of General Medicine) after expert review. 11 Verifications were made to ensure that all questions were understood. Any comment they may have regarding the understanding of the questionnaire was sought. There were no negative comments, and the answers were precise enough to enable interpretation. We did not repeat the questionnaire in order to assess the consistency in the answers because we were looking for spontaneous data.

The first portion of the questionnaire consisted of demographic and clinical practice information of the participating GPs: gender, age, geographical situation, and care management (eight closed‐ended questions). The second portion consisted of the physician's current knowledge relative to hyperkalaemia and hypokalaemia definitions and intervention with regard to dyskalaemia (four closed‐ended questions for both hyperkalaemia and hypokalaemia). The third portion concerned the management of hyperkalaemia and hypokalaemia (six open‐ended questions each) specifically in the setting of either CKD or HF history, aimed at assessing the physician's behaviour with regard to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), or MRAs using two clinical cases (Data S1).

Open‐ended questions were used in order not to influence the responses. The responses were then classified based on verbatim responses, which were subsequently grouped together when expressing the same response. Thus, ‘ion exchange resin’, sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS; Kayexalate©), and ‘hyperkalaemia drug’ were deemed as expressing the same response because there are currently no other available hyperkalaemia treatment in France other than SPS or calcium polystyrene sulfonate (Sorbisterit®). Similarly, when the GPs proposed ‘hospitalization’, ‘emergency hospitalization’, calling the ‘emergency medical service’, or calling an ‘ambulance’, these responses were also considered to express the same objective of referring the patient to an ‘emergency department’ (ED).

Ethical committee approval is not required for this type of professional survey in France, and collected data were anonymized.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) if normally distributed or as median and inter‐quartile range if the distribution was skewed. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and proportions (%).

Analyses were performed using SAS® R9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Characteristics of participating general practitioners

Five hundred GPs participated in this survey, the characteristics of whom are summarized in Table 1 . Median age was 34 years (extremes 26–69), and the majority of responders (63%) were women. There were 10/101 French administrative ‘regions’ for which we were unable to find physicians available to participate in the survey. GPs estimated that access to a cardiologist was easier than access to a nephrologist. Although the majority (67%) of GPs had an electrocardiogram (ECG) device, it was rarely used (13.6%) in dyskalaemic patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating general practitioners

| Characteristic | n | Mean ± SD/n (%) | Min–max | Median (Q1–Q3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 500 | 186 (37.2%) | ||

| Age (years) | 500 | 39.9 ± 11.7 | 26.0–69.0 | 34.0 (31.0–49.5) |

| Is there an emergency department in the city you are currently living in? | 500 | 198 (39.6%) | ||

| Is there a laboratory in the city you are living in? | 500 | 310 (62.0%) | ||

| Do you have an easy access to a cardiologist? | 500 | 429 (85.8%) | ||

| Do you have easy access to a nephrologist? | 500 | 237 (47.4%) | ||

| Do you have an ECG device? | 500 | 334 (66.8%) | ||

| If you have an ECG device, do you use it in case of hypokalaemia or hyperkalaemia? | 500 | 68 (13.6%) |

Potassium definitions and management

Thresholds to define hyperkalaemia/hypokalaemia, as well as for intervention, are presented in Table 2 . A wide range of answers were observed for both items. The mean ± SD (range) potassium level leading to ‘intervene’ (as depicted in the succeeding section) was 5.32 ± 0.34 mmol/L (4.5–6.5) for hyperkalaemia and 3.23 ± 0.34 mmol/L (2.0–6.5) for hypokalaemia. The mean ± SD potassium level for referring the patient to the ED was 6.14 ± 0.55 (4.5–10) and 2.69 ± 0.42 (1–4) mmol/L, respectively.

Table 2.

Definition of potassium levels and thresholds for intervention (n = 500)—closed‐ended questions

| Hyperkalaemia | Hypokalaemia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Min–Max | Median (Q1–Q3) | Mean ± SD | Min–Max | Median (Q1–Q3) | |

| Definition level | 5.12 ± 0.33 | 4.0–6.1 | 5.0 (5.0–5.5) | 3.38 ± 0.29 | 2.0–5.5 | 3.5 (3.3–3.5) |

| Intervention level | 5.32 ± 0.34 | 4.5–6.5 | 5.4 (5.0–5.5) | 3.23 ± 0.34 | 2.0–6.5 | 3.2 (3.0–3.5) |

| ‘ECG’ level | 5.65 ± 0.38 | 4.5–7.0 | 5.5 (5.5–6.0) | 3.02 ± 0.31 | 1.5–3.5 | 3.0 (2.9–3.2) |

| ‘ED’ level | 6.14 ± 0.55 | 4.5–10.0 | 6.0 (6.0–6.5) | 2.69 ± 0.42 | 1.0–4.0 | 2.8 (2.5–3.0) |

Hyperkalaemia management in chronic kidney disease and/or heart failure patients

Ruling out pseudo‐hyperkalaemia with a second blood sample was sought in approximately half of the cases (56%).

Dietary potassium restriction recommendations were scarcely recommended (4.6%). GPs reported that they seldom reduced or discontinued ‘drugs prone to induce hyperkalaemia’ for CKD (14%) or HF (25%) patients but frequently prescribed a potassium‐binding resin (65% or 51%, respectively). Adding a loop diuretic was uncommonly implemented (1.4% and 9.8%, respectively, for CKD and HF). GPs sought the advice of a cardiologist (for a HF patient) or nephrologist (for a CKD patient) in, respectively, 27% and 36% of cases. GPs rarely referred the HF (12.8%) or CKD (6%) patients to an ED(Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Main results for clinical hypokalaemia or hyperkalaemia management approaches (n = 500); open‐ended questions regarding chronic kidney disease or heart failure patients (in the absence of details regarding current medication)

| Potassium management | Hyperkalaemia | Hypokalaemia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second blood test for confirmation *** | 282 (56.4%) | ||||

| Dietary measures****** | 23 (4.6%) | 15 (3.0%) | |||

| Clinical examination****** | 208 (41.6%) | 132 (26.4%) | |||

| CKD patients* | HF patients** | CKD patients* | HF patients** | ||

| Biological monitoring as the only intervention | 36 (7.2%) | 36 (7.2%) | 25 (5.0%) | 21 (4.2%) | |

| Aetiology search | 142 (28.4%) | 193 (38.6%) | 232 (46.4%) | 238 (47.6%) | |

| Potassium‐modifying drug reduction or discontinuation | 71 (14.2%) | 126 (25.2%) | 140 (28.0%) | 156 (31.2%) | |

| Add or increase SPS | 325 (65.0%) | 255 (51.0%) | Add or increase K + supplement | 334 (66.8%) | 368 (73.6%) |

| Add or increase loop diuretic | 7 (1.4%) | 49 (9.8%) | Add or increase MRAs | 7 (1.4%) | 20 (4.0%) |

| Seek advice from a cardiologist | 8 (1.6%) | 135 (27.0%) | 14 (2.8%) | 103 (20.6%) | |

| Seek advice from a nephrologist | 181 (36.2%) | 22 (4.4%) | 142 (28.4%) | 18 (3.6%) | |

| Referral to ED or hospitalization | 30 (6.0%) | 64 (12.8%) | 23 (4.6%) | 30 (6.0%) | |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; ED, emergency department; HF, heart failure; MRAs, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; SPS, sodium polystyrene sulfonate.

Legend: Corresponding questions:

Question 2.1. In the presence of hyperkalaemia/hypokalaemia at levels defined from (Question 1.2 to Question 1.4) in a patient with CKD, what is your approach?

Question 2.2. And if this patient has HF, what is your approach?

Data extracted from open‐ended Questions 2.1 and 2.2 considered together.

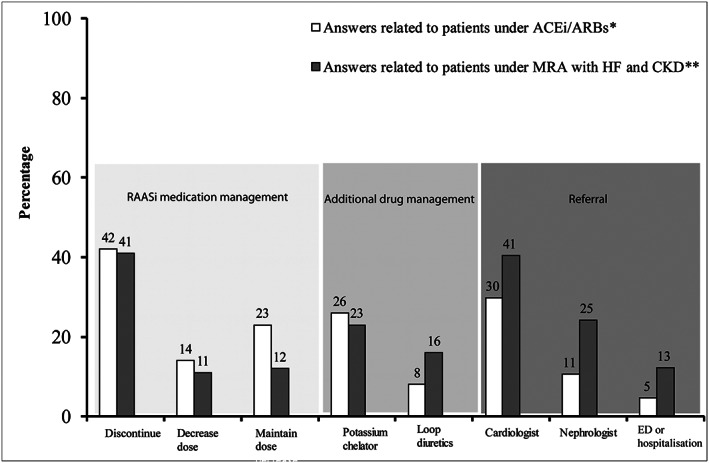

When GPs were specifically asked regarding their behaviour when confronted with hyperkalaemia in patients treated with an ACEi/ARB (without any detail regarding medical history) and in patients with HF and CKD treated with an MRA (Figure 1 ), discontinuing the drug was the option most often chosen (~40%), whereas down‐titration was seldom proposed (~10–15%). Maintaining the same doses was not uncommon (~10–20%), along with the prescription of a potassium binder (~20–30%), while loop diuretic prescription was relatively sparse (8–15%). Seeking a specialist's advice was quite common, and more frequent for a cardiologist (30–40% depending on the drug) than a nephrologist (10–25% depending on the drug). The declared approach was only very moderately modified by the clinical setting (HF and/or CKD).

Figure 1.

Initial GP behaviour (n = 500) in the presence of hyperkalaemia (level according to each physician) in patients treated with ACEi/ARBs (in the absence of details regarding medical history) or in patients with HF and/or CKD treated with MRA. *Refer to open‐ended Question 2.5: In the presence of hyperkalaemia at a threshold defined in Question 1.2 to Question 1.4, what is your approach in a patient under renin–angiotensin system inhibitor (ACEi/ARB) treatment? (several answers were possible). **Refer to open‐ended Question 2.3: In a patient with HF and CKD, under aldosterone antagonist (MRA) (Aldactone© spironolactone; or Inspra©, eplerenone) treatment, what is your approach in the presence of hyperkalaemia at a threshold defined in (Question 1.2 to Question 1.4)? (several answers were possible). Legend: HF, heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ACEi, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; ED or hospitalization, emergency department or hospitalization; GP, general practitioner; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

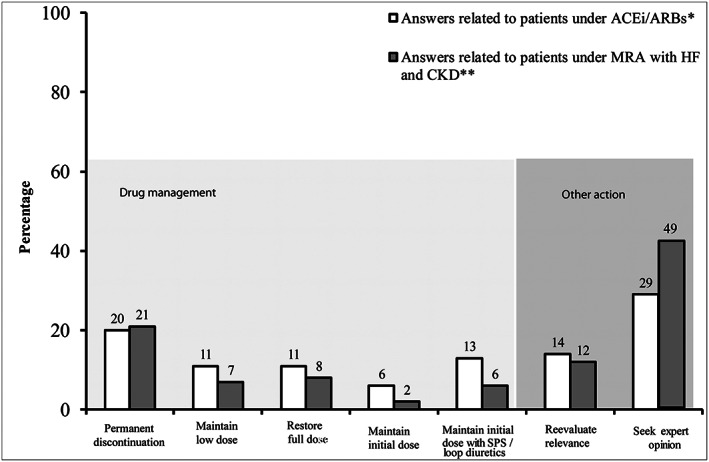

Once normalization was achieved, the most common practice (~20%) was the permanent discontinuation of ACEi/ARB or MRA. In contrast, ~10% of GPs reported maintaining a low dose of ACEi/ARB or MRA following normalization, while a similar proportion reported restoring the initial dose (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

GP approach (n = 500) after normalization of hyperkalaemia in patients under ACEi/ARBs (in the absence of details regarding medical history) and patients under MRA and history of HF and CKD. *Refer to open‐ended question 2.6: After resolution of hyperkalaemia, what is your approach toward these drugs (ACEi/ARBs)? (several answers were possible). **Refer to open‐ended question 2.4: After resolution of hyperkalaemia, what is your approach toward these drugs (Aldactone©, spironolactone; or Inspra©, eplerenone)? (several answers were possible). Legend: HF, heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ACEi, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; SPS, sodium polystyrene sulfonate; GP, general practitioner; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

Hypokalaemia management in chronic kidney disease or in heart failure patients

Approximately 50% of the GPs reported seeking the aetiology of hypokalaemia in patients with either CKD or HF (Table 3). Discontinuation or down‐titration of potassium‐modifying drugs was commonly reported (~30%), and potassium supplements were frequently reported to be prescribed (~70%). MRA use was scarcely reported (<5%), while none of the participants reported prescribing other potassium‐modulating agents such as ACEi/ARB use. In these patients, GPs were more prone to refer CKD patients to a nephrologist (~30%) than HF patients to a cardiologist (<10%).

Finally, descriptive exploratory subgroup analyses

Considering gender, age (younger or older than 40 years) of the participating GPs, and high‐income/low‐income regions did not identify specific patterns regarding the multidimensional aspect of dyskalaemia management (data not shown). If any, we identified an association between the close vicinity of GP office from an ED and ‘referring an HF patient’ (19.2% with ED vs. 8.6% without ED) and ‘referring an HF and CKD patient on MRA’ (16.7% with ED vs. 9.3% without ED).

Discussion

This study is, to our knowledge, the first survey depicting declared GP practices regarding dyskalaemia, and it provides a number of noteworthy findings. The management of potassium disturbances appears to be very heterogeneous with regard to both dyskalaemia thresholds (for diagnosis and intervention) and management patterns. The latter most likely mirror the variety of available therapeutic options. Of note, in all likelihood, country‐specific feature was the widespread use of potassium binders to manage hyperkalaemia (with a parallel widespread use of potassium supplementation to treat hypokalaemia). Another major finding is that GPs uncommonly referred their dyskalaemic patients to cardiologists and nephrologists (or the ED, if the latter was deemed necessary owing to the severity of the dyskalaemia) and that their management of potassium disorders was only very moderately modified by the presence or absence of HF and/or CKD (Figure 1). Of note, the patterns we observed generally did not differ between women and men and between younger and older GPs.

Reported thresholds for defining hyperkalaemia and hypokalaemia in this primary care setting were found to be consistent with those typically recommended in various guidelines. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 A clear stepwise approach (i.e. the stronger the severity of the dyskalaemia, the higher the likelihood to perform an ECG and to refer the patient to the ED) was identified.

Few practitioners perform an ECG in case of dyskalaemia even though they own the device. ECG is nevertheless recommended when confronted with dyskalaemia in the emergency setting. 6 , 7 Importantly, ECG was repeatedly shown to be an insensitive indicator of the severity of hyperkalaemia because cardiac manifestations can be non‐specific or even absent at potassium levels that are associated with an increased mortality risk. 9 , 12 , 13 Despite the latter, recent attempts to detect hyperkalaemia with only two‐lead ECG have been developed 14 and may ultimately lead to practice changes.

The management of potassium disorders is highly heterogeneous, which most likely coincides with the variety of available treatment approaches. It should be noted that the treatment approach for patients with hyperkalaemia is currently undergoing change with the recent availability in the USA and European Union of new‐generation potassium binders, 4 which, as of yet, are not reimbursed in France. Until recently, the recommendations were to (i) restrict the dietary potassium intake; (ii) avoid potassium supplements and drugs affecting renal function; and (iii) initiate a non‐potassium‐sparing diuretic or increase the dose if already receiving a diuretic 15 (which, however, may lead to excessive fluid depletion and a worsening in renal function, along with an overstimulation of the RAAS). 16 The latter is unfortunate, owing to the major role of RAASi including MRAs in the cardiorenal continuum, as emphasized subsequently.

In the present survey, physicians very rarely raised in a spontaneous manner the notion of dietary measures (4.6% in hyperkalaemia and 3% in hypokalaemia). It should nevertheless be emphasized that the sustainability of such dietary restrictions (for hyperkalaemia) on the long term is questionable and may eventually deprive patients of ‘healthy’ foods, that is, a Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet. We recently 17 reported a retrospective chart review depicting recurrent hyperkalaemia management practices in five European countries (including France) by interviewing 500 physicians (including 50 cardiologists and 50 nephrologists per country). In this latter study, ~91% of nephrologists and 85% of cardiologists (consistent results were observed in France) declared having prescribed a low‐potassium diet. Of note, the above physicians were interviewed regarding their management of recurrent hyperkalaemia using a closed‐ended questionnaire, whereas open‐label questions were asked to our GPs in the current study.

A predominant approach for treating hyperkalaemia reported in the present study consisted of the discontinuation or down‐titration of RAASi, whereas, of note, their up‐titration was by contrast never proposed in the setting of hypokalaemia. ACEi, ARBs, and MRAs may inherently expose them to an increased risk of hyperkalaemia, particularly when administered in combination, 18 while RAASi is among the drugs that confer the most significant survival benefit in patients with cardiovascular and renal diseases. Indeed, major clinical trials in HF have demonstrated a reduction in both cardiovascular and overall mortality with RAASi treatment leading to a Class I indication in major European and US guidelines. 19 Compliance to these guidelines 20 and the prescription of guideline‐recommended target doses has moreover been found to be associated with better outcomes in observational studies. 21 Current international CKD guidelines recommend using RAASi in order to achieve nephro‐protection, because they enable preserving kidney function and delay the progression to dialysis in CKD. 4 , 22 Recent guidelines further propose algorithms for therapeutic dose adjustment in case of hyperkalaemia. 23 Notwithstanding the latter, observational studies have nonetheless shown suboptimal MRA use, dose titration, and poor clinical follow‐up. 22 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 In a recent observational study including all Stockholm citizens initiating MRA therapy, the development of hyperkalaemia within a year was associated with a four‐fold significantly higher risk in overall mortality. Following the occurrence of hyperkalaemia, 47% discontinued MRA, whereas only 10% reduced the prescribed dose. Strikingly, when MRA was discontinued, most patients (76%) were not reintroduced to MRA therapy during the subsequent year. 24 Depriving patients of RAASi, highly recommended treatments based on a very high level of evidence, may ultimately lead to worse outcomes in the cardiorenal continuum. 17

In the present study, SPS prescription and potassium supplementation for hyperkalaemia and hypokalaemia treatments, respectively, were highly prevalent. Of note, with regard to hyperkalaemia, GPs did not cite bicarbonates (used in 10% of cases by French nephrologists and cardiologists) and barely prescribed loop diuretics (compared to ~48% prescription rate in France among nephrologists and cardiologists according to our previous study). 17 Thiazide diuretics were just not quoted by the GP participants.

The high prescription rate of SPS reported herein is specific to France, corroborating previous studies, 28 , 29 including our latest study (~45%), 17 whereas SPS is much less prescribed in other countries, 17 with concerns regarding its safety being repeatedly raised. 30 Patients with HF and/or CKD or with cardiovascular co‐morbidity are complex patients to manage and most often warrant a multidisciplinary approach. While access to a cardiologist was reported herein as relatively easy (85.8%), access to a nephrologist reportedly remained more difficult (47.4%). Access to a cardiologist's or nephrologist's advice is largely dependent on current French medical demographics. There is a shortage of these two specialists in France, which delays access to consultation, but also makes direct access by telephone difficult. This may contribute to the poor cooperation between the GPs and these specialists. Of note, we did not identify regional differences in the dyskalaemia management pattern, while the closed vicinity of GPs' office and ED was found to be associated with more referrals.

Ultimately, GPs rarely referred to a cardiologist or nephrologist in a situation of hyperkalaemia or hypokalaemia. These two specialists may also carry different messages and different practices as previously described, 17 which may lead to some confusion on the part of GPs and ultimately deprive their HF or CKD patients of life‐saving drugs (in case of a permanent discontinuation of RAASi). Acknowledging that there are no specific recommendations for the management of dyskalaemia in general practice, while there are cardiology and nephrology guidelines, with some inconsistencies, our main hypothesis is indeed that GPs might be somehow confused by different treatment options suggested by cardiologists versus nephrologists. We propose that including GPs in future guideline development may increase their applicability.

In our view, the heterogeneity observed in the present study strongly highlights the need to develop algorithms aimed at standardizing outpatient management practices and possibly avoid inaccurate behaviour, such as therapeutic inertia (e.g. no potassium recheck, no drug changes or RAASi dose maintenance in the setting of hyperkalaemia, and lack of mitigation strategy). A major strength of this survey is the in‐depth analysis of open‐ended questionnaires, which allowed accurately retrieving the heterogeneity of potassium disorder management.

The present study has several limitations. First, our study likely presents a selection bias: the population is not representative of the overall GP population in France given that the average age of the participating GPs was noticeably younger (39.9 vs. 50.6 years 31 ); indeed, the GPs who accepted the phone interview responded initially mostly via the Internet and had been contacted through social networks. In the same manner, the proportion of men and women also differed from the overall population of French GPs (62.8% vs. 48.2% 31 ). Secondly, there may be a possible imbalance between rural and urban areas, because the professional location of the GPs was not collected in most instances. Thirdly, the collected data were declarative and not corroborated by patient record review. Our original approach confronted the doctor with everyday situations and was deemed the most suitable to seek relevant insights on the management of dyskalaemia by GPs. Fourthly, thiazides were not spontaneously quoted by the GPs, while asking them specifically—which we did not—might have been informative.

Finally, the external validity could be questioned owing to the widespread use of ‘old‐generation’ potassium binders in France compared with other countries. However, the recent availability of better‐tolerated potassium binders may ultimately lead to a widespread use of these compounds in other countries.

Conclusions

Owing to the major heterogeneity of French GP practices toward hypokalaemia and hyperkalaemia diagnosis and management practices in their outpatients, including those with HF and or CKD, there is a likely need to standardize (potentially enabled by therapeutic algorithms) and evaluate standardized practices.

Conflict of interest

L.A.V., Z.L., and J.M.B. have nothing to declare. P.R. reports personal fees (consulting) from Idorsia and G3P and honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, CVRx, Fresenius, Grunenthal, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Servier, Stealth Peptides, Ablative Solutions, Corvidia, Relypsa, and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma; outside the submitted work, P.R. is the cofounder of CardioRenal. N.G. reports personal fees (consulting) for Novartis and Boehringer, outside of the submitted work.

Supporting information

Data S1. Telephone survey.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Fabien Abensur Vuillaume for help in questionnaire data entry into the database. L.A.V., P.R., Z.L., N.G., and J.M.B. are supported by the RHU Fight‐HF, a public grant overseen by the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of the second ‘Investissements d'Avenir’ programme (reference: ANR‐15‐RHUS‐0004), and by the French PIA project ‘Lorraine Université d'Excellence’ (reference: ANR‐15‐IDEX‐04‐LUE).

Abensur Vuillaume, L. , Rossignol, P. , Lamiral, Z. , Girerd, N. , and Boivin, J.‐M. (2020) Hyperkalaemia and hypokalaemia outpatient management: a survey of 500 French general practitioners. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 2042–2050. 10.1002/ehf2.12834.

References

- 1. Nunez J, Bayes‐Genis A, Zannad F, Rossignol P, Nunez E, Bodi V, Minana G, Santas E, Chorro FJ, Mollar A, Carratala A, Navarro J, Gorriz JL, Lupon J, Husser O, Metra M, Sanchis J. Long‐term potassium monitoring and dynamics in heart failure and risk of mortality. Circulation 2017; 137: 1320–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goyal A, Spertus JA, Gosch K, Venkitachalam L, Jones PG, Van den Berghe G, Kosiborod M. Serum potassium levels and mortality in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2012; 307: 157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rossignol P, Duarte K, Girerd N, Karoui M, McMurray J, Swedberg K, van Veldhuisen DJ, Pocock S, Dickstein K, Zannad F, Pitt B. Cardiovascular risk associated with serum potassium in the context of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist use in patients with heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction. Eur J H Fail 2020. 10.1002/ejhf.1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rossignol P. A new area for the management of hyperkalaemia with potassium binders: clinical use in nephrology. Eur Heart J Suppl 2019; 21: A48–A54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, Oates JA, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW, American College of Cardiology F, American Heart A . 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53: e1–e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alfonzo A, Soar J, MacTier R, Fox J, Shillday I, Nolan J, Kishen R, Douglas A, Bartlett B, Wiese M, Wilson B, Beatson J, Allen L, Goolam M, Whittle M. Clinical practice guidelines treatment of acute hyperkalaemia in adults UK Renal Institution; 2014. https://renal.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/hyperkalaemia-guideline-1.pdf (11 November 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Truhlář A, Deakin CD, Soar J, Khalifa GEA, Alfonzo A, Bierens JJLM, Brattebø G, Brugger H, Dunning J, Hunyadi‐Antičević S, Koster RW, Lockey DJ, Lott C, Paal P, Perkins GD, Sandroni C, Thies K‐C, Zideman DA, Nolan JP, Barelli A, Böttiger BW, Georgiou M, Handley AJ, Lindner T, Midwinter MJ, Monsieurs KG, Wetsch WA. European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2015. Resuscitation 2015; 95: 148–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dépret F, Peacock WF, Liu KD, Rafique Z, Rossignol P, Legrand M. Management of hyperkalemia in the acutely ill patient. Ann Intensive Care 2019; 9: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rossignol P, Legrand M, Kosiborod M, Hollenberg SM, Peacock WF, Emmett M, Epstein M, Kovesdy CP, Yilmaz MB, Stough WG, Gayat E, Pitt B, Zannad F, Mebazaa A. Emergency management of severe hyperkalemia: guideline for best practice and opportunities for the future. Pharmacol Res 2016; 113: 585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garcia P, Belhoula M, Grimaud D. Les dyskaliémies SFAR; 1999. https://www.urgences-serveur.fr/IMG/pdf/les_dyskaliemies_99.pdf (11 November 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bouletreau A, Chouaniere D, Wild P, Fontana JM. Concevoir, traduire et valider un questionnaire. A propos d'un exemple EUROQUEST. Notes scientifiques et techniques de l'INRS NS 178. Institut National de Recherche et de Sécurité (INRS); 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mattu A, Brady W, Robinson DA. Electrocardiographic manifestations of hyperkalemia. Am J Emerg Med 2000; 18: 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Montague BT, Ouellette JR, Buller GK. Retrospective review of the frequency of ECG changes in hyperkalemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3: 324–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Galloway CD, Valys AV, Shreibati JB, Treiman DL, Petterson FL, Gundotra VP, Albert DE, Attia ZI, Carter RE, Asirvatham SJ, Ackerman MJ, Noseworthy PA, Dillon JJ, Friedman PA. Development and validation of a deep‐learning model to screen for hyperkalemia from the electrocardiogram. JAMA Cardiol 2019; 4: 428–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kovesdy CP. Management of hyperkalemia: an update for the internist. Am J Med 2015; 128: 1281–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zannad F, Rossignol P. Cardiorenal syndrome revisited. Circulation 2018; 138: 929–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rossignol P, Ruilope LM, Cupisti A, Ketteler M, Wheeler DC, Pignot M, Cornea G, Schulmann T, Lund LH. Recurrent hyperkalaemia management and use of reninangiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors. A European multi‐national targeted chart review. Clin Kidney J 2019. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weir MR, Rolfe M. Potassium homeostasis and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5: 531–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rossignol P, Hernandez AF, Solomon SD, Zannad F. Heart failure drug treatment. Lancet 2019; 393: 1034–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Komajda M, Lapuerta P, Hermans N, Gonzalez‐Juanatey JR, van Veldhuisen DJ, Erdmann E, Tavazzi L, Poole‐Wilson P, Le Pen C. Adherence to guidelines is a predictor of outcome in chronic heart failure: the MAHLER survey. Eur Heart J 2005; 26: 1653–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ouwerkerk W, Voors AA, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, van der Harst P, Hillege HL, Lang CC, Ter Maaten JM, Ng LL, Ponikowski P, Samani NJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, Zannad F, Metra M, Zwinderman AH. Determinants and clinical outcome of uptitration of ACE‐inhibitors and beta‐blockers in patients with heart failure: a prospective European study. Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 1883–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pecoits‐Filho R, Fliser D, Tu C, Zee J, Bieber B, Wong MMY, Port F, Combe C, Lopes AA, Reichel H, Narita I, Stengel B, Robinson BM, Massy Z, Investigators CK. Prescription of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi) and its determinants in patients with advanced CKD under nephrologist care. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2019; 21: 991–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rosano GMC, Tamargo J, Kjeldsen KP, Lainscak M, Agewall S, Anker SD, Ceconi C, Coats AJS, Drexel H, Filippatos G, Kaski JC, Lund L, Niessner A, Savarese G, Schmidt TA, Seferovic P, Wassmann S, Walther T, Lewis BS. Expert consensus document on the management of hyperkalaemia in patients with cardiovascular disease treated with RAAS‐inhibitors—Coordinated by the Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2018; 4: 180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Trevisan M, de Deco P, Xu H, Evans M, Lindholm B, Bellocco R, Barany P, Jernberg T, Lund LH, Carrero JJ. Incidence, predictors and clinical management of hyperkalaemia in new users of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. Eur J Heart Fail 2018; 20: 1217–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maggioni AP, Anker SD, Dahlström U, Filippatos G, Ponikowski P, Zannad F, Amir O, Chioncel O, Leiro MC, Drozdz J, Erglis A, Fazlibegovic E, Fonseca C, Fruhwald F, Gatzov P, Goncalvesova E, Hassanein M, Hradec J, Kavoliuniene A, Lainscak M, Logeart D, Merkely B, Metra M, Persson H, Seferovic P, Temizhan A, Tousoulis D, Tavazzi L, ESC. HFAot. Are hospitalized or ambulatory patients with heart failure treated in accordance with European Society of Cardiology guidelines? Evidence from 12 440 patients of the ESC Heart Failure Long‐Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:1173–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Allen LA, Shetterly SM, Peterson PN, Gurwitz JH, Smith DH, Brand DW, Fairclough DL, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, Magid DJ. Guideline concordance of testing for hyperkalemia and kidney dysfunction during initiation of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist therapy in patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2014; 7: 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cooper LB, Hammill BG, Peterson ED, Pitt B, Maciejewski ML, Curtis LH, Hernandez AF. Consistency of laboratory monitoring during initiation of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist therapy in patients with heart failure. JAMA 2015; 10: 1973–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wagner S, Metzger M, Flamant M, Houillier P, Haymann JP, Vrtovsnik F, Thervet E, Boffa JJ, Massy ZA, Stengel B, Rossignol P, NephroTest Study g . Association of plasma potassium with mortality and end‐stage kidney disease in patients with chronic kidney disease under nephrologist care mdash;The NephroTest study. BMC Nephrol 2017; 18: 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rossignol P, Lamiral Z, Frimat L, Girerd N, Duarte K, Ferreira J, Chanliau J, Castin N. Hyperkalaemia prevalence, recurrence and management in chronic haemodialysis: a prospective multicentre French regional registry 2‐year survey. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017; 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Noel JA, Bota SE, Petrcich W, Garg AX, Carrero JJ, Harel Z, Tangri N, Clark EG, Komenda P, Sood MM. Risk of hospitalization for serious adverse gastrointestinal events associated with sodium polystyrene sulfonate use in patients of advanced age. JAMA Intern Med 2019; 179: 1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bouet P. Atlas de la démographie médicale en France. 2018. https://www.conseil-national.medecin.fr/sites/default/files/external-package/analyse_etude/hb1htw/cnom_atlas_2018_0.pdf (14 June 2019).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Telephone survey.