ABSTRACT

Aim

To compare the efficacy and safety between modified quadruple- and bismuth-containing quadruple therapy as first-line eradication regimen for Helicobacter pylori infection.

Methods

This study was a multicenter, randomized-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Subjects endoscopically diagnosed with H. pylori infection were randomly allocated to receive modified quadruple- (rabeprazole 20 mg bid, amoxicillin 1 g bid, metronidazole 500 mg tid, bismuth subcitrate 300 mg qid [elemental bismuth 480 mg]; PAMB) or bismuth-containing quadruple therapy (rabeprazole 20 mg bid, bismuth subcitrate 300 mg qid, metronidazole 500 mg tid, tetracycline 500 mg qid; PBMT) for 14 days. Rates of eradication success and adverse events were investigated. Antibiotic resistance was determined using the agar dilution and DNA sequencing of the clarithromycin resistance point mutations in the 23 S rRNA gene of H. pylori.

Results

In total, 233 participants were randomized, 27 were lost to follow-up, and four violated the protocol. Both regimens showed an acceptable eradication rate in the intention-to-treat (PAMB: 87.2% vs. PBMT: 82.8%, P = .37), modified intention-to-treat (96.2% vs. 96%, P > .99), and per-protocol (96.2% vs. 96.9%, P > .99) analyses. Non-inferiority in the eradication success between PAMB and PBMT was confirmed. The amoxicillin-, metronidazole-, tetracycline-, clarithromycin-, and levofloxacin-resistance rates were 8.3, 40, 9.4, 23.5, and 42.2%, respectively. Antimicrobial resistance did not significantly affect the efficacy of either therapy. Overall compliance was 98.1%. Adverse events were not significantly different between the two therapies.

Conclusion

Modified quadruple therapy comprising rabeprazole, amoxicillin, metronidazole, and bismuth is an effective first-line treatment for the H. pylori infection in regions with high clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance.

KEYWORDS: Helicobacter pylori, disease eradication, bismuth, metronidazole, drug resistance

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is associated with various diseases, including gastritis, peptic ulcer, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, gastric adenocarcinoma, or immune thrombocytopenic purpura.1-4 Eradication of this pathogen can cure the associated diseases or alter their clinical course.5 Clarithromycin-containing triple therapy has been the primary regimen worldwide.6 However, due to high rate of clarithromycin resistance, the current eradication rate of this therapy has fallen below 80% in Korea, which is unacceptable as a first-line eradication regimen.7-9

The recent nationwide antibiotic resistance mapping of H. pylori in Korea showed that the clarithromycin resistance rate is over 15%; the metronidazole resistance is 30–40% in Gyeonggi and 40–50% in Gangwon province, respectively.10 The rate of dual clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance is approximately 6–8%; therefore, bismuth-containing quadruple or concomitant therapy is recommended as an alternative first-line regimen according to the major guidelines.1-3

However, concomitant therapy is not recommended in regions with high metronidazole resistance, and the rate of metronidazole resistance has been reported to be up to 66% in Korea.11 Moreover, dual clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance undermines the efficacy of concomitant therapy.1 There is also no definite second-line or third-line rescue regimen for patients who do not respond to the above therapies as high quinolone resistance has been reported, and there are concerns about the emergence of rifabutin-resistant mycobacteria in Korea.5 Therefore, determining an optimal regimen for first-line eradication is warranted.

The Maastricht V/Florence consensus report stated that if tetracycline is not available in regions with high levels of dual resistance, the modified (bismuth-containing) quadruple therapy, combining amoxicillin plus metronidazole (proton-pump inhibitor [PPI], amoxicillin, metronidazole, bismuth; PAMB) can be considered.1 However, this evidence is based only on the results of one study that investigated the efficacy of a combination of PPI, amoxicillin, furazolidone, and bismuth (PAFB), rather than the PAMB regimen.12

A recent Korean study has shown that PAMB has eradication success and adverse events rates comparable to those of concomitant therapy13 and a recent Iranian study revealed that PAMB is superior to bismuth-containing quadruple therapy.14 However, these studies did not explore the antibiotic resistance profile of H. pylori, which makes it difficult to interpret their results.

A previous Chinese study also revealed that PAMB regimen had high and non-inferior eradication success compared to that of the combination of PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and bismuth potassium citrate (PACB).15 However, there have been no comparative studies on PAMB versus bismuth-containing quadruple therapy as a first-line regimen in cases of antibiotic resistance, except for comparisons in a rescue therapy setting.16

Therefore, this study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety between modified quadruple- and bismuth-containing quadruple therapy as a first-line eradication regimen and to provide an antibiotic resistance profile of H. pylori.

Methods

Design of the trial

This was an open-label, multicenter, randomized-controlled, non-inferiority trial of subjects with H. pylori infection. They were randomly assigned to receive either modified quadruple- (rabeprazole 20 mg bid, amoxicillin 1 g bid, metronidazole 500 mg tid, bismuth subcitrate [De-Nol®] 300 mg qid daily) or bismuth-containing quadruple therapy (rabeprazole 20 mg bid, tetracycline 500 mg qid, metronidazole 500 mg tid, bismuth subcitrate 300 mg qid daily; PBMT) for 14 days. The eradication success, treatment-related adverse events, and compliance were investigated and compared between the two therapies.

Subjects of the trial

Participants were recruited from two Hospitals (Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital in Gangwon and Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital in Gyeonggi province) from August 2018 to July 2019.

Subjects who underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and were proven to have H. pylori infection either by using the rapid urease test, the 13 C-urea breath test (UBT), or histological examination were included. Subjects who took medications as PPI, Histamin-2 receptor antagonist and antibiotics, who underwent stomach resection and less than 18 years of age, were excluded from this study. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria is described in the protocol of this trial.17

Outcome measurement

H. pylori infection was diagnosed using one or more of the following methods: rapid urease test, UBT, or histological examination. Two specimens from the gastric corpus and two specimens from the antrum were taken during endoscopy for the rapid urease test (Pronto Dry New®; Medical Instruments Corp., Herford, Germany) or histological assessment using Giemsa staining. After administering eradication therapy for H. pylori, a UBT (UBiT-IR 300; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was performed at least 4 weeks after termination of medications. Delta over baseline >2.5‰ was considered positive.17

All the subjects were educated about adverse events related to the eradication medications, and they were asked to submit self-reported questionnaires at the first visit (2 weeks after ending the eradication regimen) and at the second visit (6 weeks after enrollment). The severity of the adverse events was classified as ‘mild’ (transient and well-tolerated), ‘moderate’ (causing discomfort and partially interfering with daily activities), or ‘severe’ (causing considerable interference with daily activities).16 Potential adverse events were monitored by the research staff for 3 months after enrollment. Information about adverse events related to the eradication medications was gathered from self-report questionnaires and interviews conducted by the doctors and independent staff. Compliance with the eradication regimen was checked at the first visit by independent staff.17

Randomization and blinding

Eligible participants were recruited voluntarily. An independent staff member prepared the randomization sequence, which was accomplished using a block design and a block size of four. Randomization of a block was performed according to a random-number chart. This study was an open-label trial due to the difference in administration methods for each arm. However, only the rate of eradication success, adverse events, and compliance were considered the outcomes, and it was believed that an open-label design in itself did not influence the results.17

Phenotypic and genotypic antibiotic resistance tests

For subjects who underwent endoscopy with the rapid urease test or histological examination to determine H. pylori infection, one biopsy specimen from the gastric corpus or antrum was cultured using an agar dilution to assess phenotypic antibiotic resistance. One specimen was also used to sequence the 23 S rRNA gene in clarithromycin-resistant strains to assess genotypic antibiotic resistance. For the subjects who had already undergone endoscopy before enrollment or who were diagnosed with H. pylori infection using the UBT, antibiotic resistance tests were omitted.

The MIC cutoffs were defined according to the criteria of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards: MIC value >0.5 μg/ml (amoxicillin), >8 μg/ml (metronidazole), >4 μg/ml (tetracycline), >1 μg/ml (clarithromycin), >1 μg/ml (levofloxacin), and >1 μg/ml (ciprofloxacin)18 and all sequencing work was performed by a commercial expert agency (Samkwang Medical Laboratories, Seoul, Korea). The detailed methods of phenotypic and genotypic antibiotic resistance test are described in the protocol of this trial.17

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated by using an α-error of < 0.05 and a β-error < 0.2 for a two-tailed significance test. The calculated number of subjects required for the trial was 100 in each arm, which was determined by assuming an eradication rate of 96.2% following treatment with bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for 14 days as seen in an earlier Korean study (per-protocol [PP] analysis), with an equivalence margin of 8% and a dropout rate of 10%.19

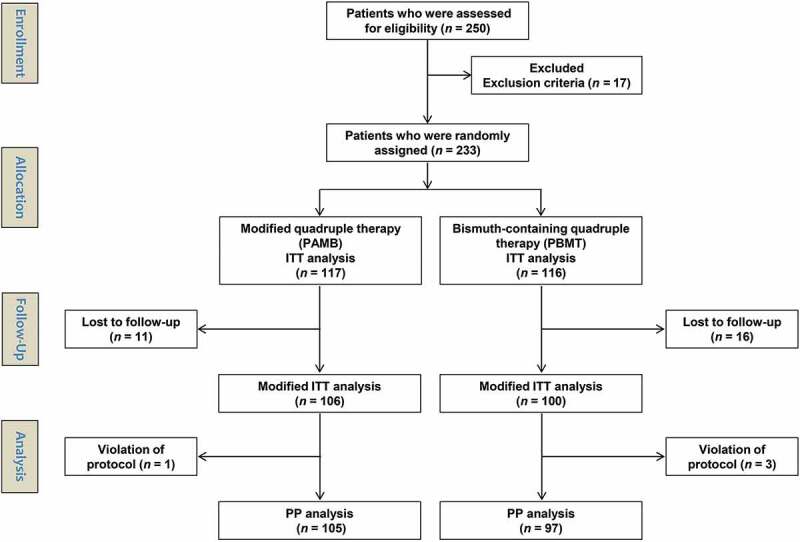

For the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, all participants who took at least the first dose of the medications were included. For the modified ITT analysis, all participants who took at least the first dose of medications and in whom the post-treatment H. pylori status could be evaluated were included. For the PP analysis, only those who maintained and completed treatment with the medications without violating the study regulations (defined as taking <80% of medications) were included (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient enrollment flow chart. ITT, intention-to-treat; PP, per-protocol; n, number.

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. First, we compared the baseline characteristics of the enrolled subjects using the Student’s t-test and Fisher’s exact test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. We then performed ITT, modified ITT, and PP analyses to compare the eradication success rate, compliance with therapies, and adverse event rate between the two arms. Subgroup analyses were performed according to the antibiotic resistance profile of the H. pylori isolate. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance for all tests except for non-inferiority test. Non-inferiority was confirmed via using Chi-squared test, and a p-value <0.25 was used as the threshold. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.17

Ethics

We received approval from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in Korea and the Institutional Review Board before the study was initiated. This study was registered at ClinicalTrial.gov in June 2018 (NCT03665428), and the protocol was published in November 2018.17 All authors had access to the study data, reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Results

Characteristics of the enrolled population

A total of 233 subjects were randomly allocated to receive either PAMB (n = 117) or PBMT (n = 116) therapy. The characteristics of the enrolled population are summarized in Table 1. The baseline characteristics were not significantly different between the two groups. Among the enrolled subjects, 11 patients in the PAMB and 16 patients in the PBMT group were lost to follow-up. One patient in the PAMB and three patients in the PBMT group violated the protocol. The flow diagram of this trial is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Variable | PAMB (n = 117) | PBMT (n = 116) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 53.7 ± 10.8 | 53.4 ± 11.4 | 0.86 |

| Sex, male/female | 59/58 | 58/58 | >0.99 |

| Smoking | 22 (18.8%) | 15 (12.9%) | 0.28 |

| Diagnosis | 0.47 | ||

| Peptic ulcer | 73 (62.4%) | 73 (62.9%) | |

| Chronic atrophic gastritis | 27 (23.1%) | 33 (28.4%) | |

| Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer or gastric adenoma | 9 (7.7%) | 4 (3.4%) | |

| Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis | 7 (6%) | 6 (5.2%) | |

| Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma | 1 (0.9%) | 0 | |

| Antibiotic resistance | |||

| Cultured | 93 (79.5%) | 87 (75%) | 0.44 |

| Amoxicillin resistance | 6 (6.5%) | 9 (10.3%) | 0.42 |

| Metronidazole resistance | 30 (32.3%) | 42 (48.3%) | 0.03 |

| Tetracycline resistance | 9 (9.7%) | 8 (9.2%) | >0.99 |

| Clarithromycin resistance* | 28 (23.9%) | 26 (22.4%) | 0.88 |

| Levofloxacin resistance | 37 (39.8%) | 39 (44.8%) | 0.55 |

| Ciprofloxacin resistance | 36 (38.7%) | 39 (44.8%) | 0.45 |

| Dual clarithromycin & metronidazole resistance | 7 (7.5%) | 5 (5.7%) | 0.77 |

| Lost to follow-up | 11 (9.4%) | 16 (13.8%) | 0.31 |

| Poor compliance (administration of less than 80% tablets) | 1 (0.9%) | 3 (3%) | 0.36 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%). *Sequencing-based results.

Eradication success rate

A total of 233 subjects were included in the ITT-, 206 subjects in the modified ITT-, and 202 subjects in the PP analysis. Both regimens showed a high eradication rate in the ITT- (PAMB: 87.2% vs. PBMT: 82.8%, p = .37), modified ITT- (PAMB: 96.2% vs. PBMT: 96%, p > .99), and PP (PAMB: 96.2% vs. PBMT: 96.9%, p > .99) analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Eradication rates of modified quadruple therapy and bismuth-containing quadruple therapy.

| PAMB | PBMT | Difference from PBMT group | p value for difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention-to-treat | ||||

| Eradication rate | 87.2% (102/117) | 82.8% (96/116) | 4.4% (95% CI: −4.7–13.6%) | 0.19 |

| Modified intention-to-treat | ||||

| Eradication rate | 96.2% (102/106) | 96% (96/100) | 0.2% (95% CI: −5.1–5.5%) | 0.06 |

| Per-protocol | ||||

| Eradication rate | 96.2% (101/105) | 96.9% (94/97) | −0.7% (95% CI: −5.7–4.3%) | 0.10 |

CI: confidence interval.

The difference in eradication rates between the two groups was 4.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]: −4.7–13.6%) in the ITT, 0.2% (95% CI: −5.1–5.5%) in the modified ITT-, and −0.7% (95% CI: −5.7–4.3%) in the PP analysis. The equivalence margin was 8% and all the p value was less than 0.25; therefore, non-inferiority was confirmed (Table 2).

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

The overall bacterial culture success rate was 77.3% (180/233). The resistance rates for amoxicillin-, metronidazole-, tetracycline-, clarithromycin-, levofloxacin-, and ciprofloxacin-resistance were 8.3% (15/180), 40% (72/180), 9.4% (17/180), 31.7% (57/180), 42.2% (76/180), and 41.6% (75/180), respectively. The rate of dual clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance was 6.7% (12/180).

Among the 233 enrolled subjects who were proven to have H. pylori infection, H. pylori was not detected in three subjects during the genotypic antibiotic resistance testing. Therefore, the success rate of genotypic antibiotic resistance testing was 98.7% (230/233). The genotypic resistance rate of clarithromycin was 23.5% (54/230), and the agreement between genotypic and phenotypic resistance had a Cohen’s kappa of 0.76 (a substantial agreement).20 Among the 54 subjects with genotypic resistance for clarithromycin, 98.1% (53/54) and 1.9% (1/54) exhibited the A2143 G mutation and the A2142 G mutation, respectively.

The antibiotic resistance profile of H. pylori was not significantly different between the two arms, except for metronidazole resistance (32.3% [30/93] in the PAMB vs. 48.3% [42/87] in the PBMT group, p = .03) (Table 1). However, subgroup analysis revealed that metronidazole resistance did not affect the efficacy of either therapy (eradication success: 100% [26/26] in the PAMB vs. 97% [32/33] in the PBMT group, p > .99). Both regimens showed acceptable efficacy, irrespective of the presence of antibiotic resistance. Even dual clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance did not affect the efficacy of either regimen (Table 3).

Table 3.

Eradication rates of modified quadruple therapy and bismuth-containing quadruple therapy in the presence of antibiotic resistance.

| Per-protocol population | PAMB | PBMT | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin resistance | 83.3% (5/6) | 83.3% (5/6) | >0.99 |

| Metronidazole resistance | 100% (26/26) | 97% (32/33) | >0.99 |

| Tetracycline resistance | 100% (7/7) | 100% (5/5) | >0.99 |

| Clarithromycin resistance* | 96.2% (25/26) | 95.8% (23/24) | >0.99 |

| Levofloxacin resistance | 97.2% (35/36) | 96.3% (26/27) | >0.99 |

| Ciprofloxacin resistance | 100% (32/32) | 93.8% (30/32) | 0.49 |

| Dual clarithromycin & metronidazole resistance | 100% (6/6) | 100% (4/4) | >0.99 |

*Sequencing-based results.

Patient compliance and adverse events

A total of 99.1% of subjects in the PAMB and 97% of subjects in the PBMT group adhered to the eradication regimen (p = .36). The overall compliance rate was 98.1% (202/206). There was no significant difference in the rate of adverse events between the PAMB and the PBMT group (29.9% vs. 30.2%, p > .99). The proportion and grade of adverse events were also not significantly different between the two therapies. The most common adverse event was diarrhea/loose stool, followed by dyspepsia, headache, fatigue, and experiencing a bitter taste (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adverse events of eradication medications.

| Variables | PAMB (n = 117) | PBMT (n = 116) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total adverse events | 35 (29.9%) | 35 (30.2%) | >0.99 |

| Grade of adverse event | 0.26 | ||

| Mild | 30 (25.6%) | 23 (19.8%) | |

| Moderate | 4 (3.4%) | 8 (6.9%) | |

| Severe | 1 (0.9%) | 4 (3.4%) | |

| Details of adverse events | |||

| Nausea | 18 (15.4%) | 18 (15.5%) | >0.99 |

| Dizziness | 3 (2.6%) | 10 (8.6%) | 0.05 |

| Abdomen pain/discomfort | 7 (6%) | 5 (4.3%) | 0.77 |

| Diarrhea/loose stool | 8 (6.8%) | 3 (2.6%) | 0.22 |

| Dyspepsia | 3 (2.6%) | 6 (5.2%) | 0.33 |

| Headache | 5 (4.3%) | 4 (3.4%) | >0.99 |

| Fatigue | 4 (3.4%) | 3 (2.6%) | >0.99 |

| Bitter taste | 2 (1.7%) | 4 (3.4%) | 0.45 |

| Epigastric soreness | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (1.7%) | >0.99 |

| Vomiting | 2 (1.7%) | 1 (0.9%) | >0.99 |

| Skin rash | 0 | 1 (0.9%) | 0.50 |

| Insomnia | 2 (1.7%) | 1 (0.9%) | >0.99 |

| Febrile sensation | 2 (1.7%) | 1 (0.9%) | >0.99 |

| Poor compliance (administration of less than 80% tablets) | 1 (0.9%) | 3 (2.6%) | 0.37 |

Discussion

Modified quadruple therapy involves the replacement of tetracycline with amoxicillin in a bismuth-containing quadruple regimen. In the present study, this regimen showed an acceptable and non-inferior eradication rate compared to that in bismuth-containing quadruple therapy with high adherence. Moreover, antimicrobial resistance did not significantly affect the efficacy. Adverse events related to the eradication medication might be interpreted as relatively high (29.9%). However, this could be due to thorough investigation through the self-report questionnaires and interviews conducted by the doctors and independent staff; the majority of the reported adverse events were ‘mild’. Discontinuation of medication due to a ‘severe’ adverse event only occurred in one subject (PAMB group) and this patient complained of nausea which was relieved with conservative management.

The reason for the high eradication rate shown by modified quadruple therapy and bismuth-containing quadruple therapy can be explained via several mechanisms. First, combining bismuth with metronidazole could induce a synergism, even making metronidazole resistant strains susceptible.21 Bismuth, which has a bactericidal effect on H. pylori, could decrease the bacterial load. Bismuth impedes proton entry into the bacteria, leading to a decrease in the expected fall in cytoplasmic pH. With pH remaining within range for increased metabolic activity of a neutrophil, the efficacy of growth-dependent antibiotics is known to be augmented.22 Second, the combination of metronidazole with rabeprazole (20 mg bid was used in this study), which is less influenced PPI through the CYP 2C19 polymorphism, might enhance the efficacy of metronidazole, irrespective of the resistant strains.23,24 The degree of acid inhibition is important in the eradication success of H. pylori. The duration with pH >4 and continuous periods with intragastric pH >6 were related to eradication success, implicating profound acid inhibition is responsible for improved eradication rates.25 Moreover, antibiotics are more stable and have higher activity at higher intragastric pHs attributed by PPIs.25 A previous Japanese study on potassium-competitive acid blocker (PCAB), which has more potent acid inhibitory effect than PPI has shown higher eradication rate than that of PPI in the extensive metabolizer, highlighting the importance of maintaining higher pH in the H. pylori eradication.26 Further research on H. pylori eradication using PCAB in subjects other than the Japanese population would elucidate this mechanism more clearly. Third, the sufficient dose of metronidazole (at least 1500 mg daily) and the extended duration of 14 days could be the reason for overcoming metronidazole resistance.27,28 Generally, a high dose and long-term duration of metronidazole administration is associated with the development of adverse events. However, this was not a significant issue during this trial, and international consensus reports have typically recommended using quadruple regimens of 14-days, unless 10-day therapies are proven effective locally.1,3 Irrespective of the mechanisms, tetracycline is not available in some countries, thus making modified quadruple therapy beneficial in these countries.

A previous Taiwanese study evaluated the efficacy of 1-week PAMB regimen against a combination of PPI, amoxicillin, bismuth, and tetracycline (PABT).29 The study found unsatisfactory and lower eradication rate of PAMB regimen compared to that of PABT, particularly in the subjects with metronidazole resistance.29 However, the treatment duration was only 1 week, and the dose of metronidazole used was less than 1500 mg daily, which is insufficient to overcome the metronidazole resistance. Moreover, antibiotic susceptibility was determined using E-test, which tends to overestimate metronidazole resistance.23 A previous Turkish study also compared the efficacy of 2-week PAMB regimen with that of PABT and PBMT.30 The treatment duration was extended to 14 days, and the eradication success was not different between the therapies. However, the treatment indication was second-line rescue for patients who failed previous clarithromycin-containing triple regimen. Further, the dosage of metronidazole was less than 1500 mg daily.30 A recent Iranian study compared the efficacy of 2-week PAMB with that of PBMT using a protocol similar to the current study.14 The eradication success rate was higher (95.5% vs.83.8% in the PP analysis) and the adverse events were lower (43.4% vs. 65.2%) in the PAMB group.14 However, only patients with duodenal ulcer were enrolled without providing antibiotic resistance profile in this study.14 The most important point relevant to the studies about PAMB regimen is the lack of antibiotic susceptibility test, which makes it hard to interpret the results. A recent Korean study evaluating PAMB vs. concomitant regimen also omitted this analysis.13 Only two Chinese studies conducted in 2015 (PAMB vs. PACB) and 2016 (PAMB vs. PBMT in a third-line rescue regimen)15,16 presented antibiotic resistance profiles, and both showed good efficacy of PAMB regimen, even in areas with high metronidazole and clarithromycin resistance.

Recently published two randomized controlled trials in China commonly revealed the favorable efficacy of high-dose amoxicillin containing regimens, irrespective of the addition of bismuth.31,32 High-dose dual therapy including esomeprazole 40 mg bid, and amoxicillin 1 g tid with or without elemental bismuth 220 mg bid for 2 weeks showed comparable efficacy (over 90% eradication success in the PP analysis), irrespective of the antibiotic resistance.31 Study of PAMB vs. PAM regimen including high dose amoxicillin (esomeprazole 20 mg bid, amoxicillin 1 g tid, and metronidazole 400 mg tid with or without 220 mg elemental bismuth bid) for 2 weeks also showed comparable efficacy (over 90% eradication success in the PP analysis), irrespective of the antibiotic resistance.32 Although metronidazole resistance can be overcome with the additive effect of bismuth, both bismuth and high-dose amoxicillin can both independently theoretically improve treatment outcomes.32 However, the favorable efficacy of high-dose dual therapy have not been reproduced in Korean studies.33,34 Further research is needed considering the efficacy classified according to the dose of amoxicillin, the degree of corpus gastritis, and CYP2C19 polymorphisms because these factors are influential on the therapeutic efficacy and may differ depending on the target population.

Despite the favorable efficacy of modified quadruple therapy, it is not indicated for patients with penicillin allergy. However, an amoxicillin-containing regimen, such as clarithromycin-based triple therapy, has primarily been the first-line regimen worldwide. Considering that most patients with a history of penicillin allergy do not have true hypersensitivity, 2 this should not be a barrier for providing alternative first-line eradication regimen. The complexity of the administration method is a limitation. However, detailed medication education and counseling would enhance the adherence to therapy ;35,36 in this trial, compliance was remarkably high.

This study compared the efficacy and safety of modified quadruple- and bismuth-containing quadruple therapy and described the antibiotic resistance profiles of H. pylori. The strength of this study is that it provides evidence on the efficacy and safety of both therapies as a first-line regimen in different regions. The antibiotic resistance profile was measured using the agar dilution and clarithromycin resistance was validated using genotypic resistance sequencing.

Despite these strengths, this study also has several limitations. Only one biopsy specimen could be obtained to determine the antibiotic resistance. The cultured or sequenced H. pylori from only one sample of the biopsied specimen may not accurately represent the bacterial flora of the entire stomach.37 Furthermore, a detailed comparison between the phenotypic and genotypic antibiotic resistance was not possible. This was because the agreement between the two methods was substantial, and the most commonly detected point mutations were the A2143 G mutations, except for only one strain with the A2142 G mutation. Further research involving PCAB with metronidazole or simplified combination medication avoiding complex administration method will more clearly elucidate the real value of modified quadruple regimen.

In conclusion, modified quadruple therapy is an effective alternative first-line regimen for the eradication of H. pylori in regions with high clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Hallym University Research Fund 2018 (number: HURF-2018-39) and the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) & by the Korean government, Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) (number: NRF2017M3A9E8033253).

Guarantor of the article

Chang Seok Bang, MD, PhD. Hyun Lim, MD, PhD.

Specific author contributions

Study design, data acquisition, statistical analysis, interpretation, drafting of the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript: CS Bang; patient recruitment, acquisition of data, drafting of the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript: H Lim; patient recruitment and study coordination: HM Jeong, WG Shin, JS Soh, HS Kang, YJ Yang, JT Hong, SP Shin, KT Suk, GH Baik, DJ Kim; Phenotypic antibiotic resistance test: JH Choi; study supervision and technical support: JJ Lee

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY, et al. Management of helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence consensus report. Gut. 2017;66:6–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF.. ACG clinical guideline: treatment of helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(2):212–239. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fallone CA, Chiba N, van Zanten SV, Fischbach L, Gisbert JP, Hunt RH, Jones NL, Render C, Leontiadis GI, Moayyedi P, et al. The toronto consensus for the treatment of helicobacter pylori infection in adults. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(1):51–69.e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, Graham DY, El-Omar EM, Miura S, Haruma K, Asaka M, Uemura N, Malfertheiner P, et al. Kyoto global consensus report on helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64(9):1353–1367. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi JH, Yang YJ, Bang CS, Lee JJ, Baik GH. Current status of the third-line helicobacter pylori eradication. Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2018;2018:6523653. doi: 10.1155/2018/6523653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SG, Jung HK, Lee HL, Jang JY, Lee H, Kim CG, Shin WG, Shin ES, Lee YC. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea, 2013 revised edition. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1371–1386. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JW, Kim N, Kim JM, Nam RH, Chang H, Kim JY, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH, Jung HC, et al. Prevalence of primary and secondary antimicrobial resistance of helicobacter pylori in Korea from 2003 through 2012. Helicobacter. 2013;18(3):206–214. doi: 10.1111/hel.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim BJ, Kim HS, Song HJ, Chung I-K, Kim GH, Kim B-W, Shim K-N, Jeon SW, Jung YJ, Yang C-H, et al. Online registry for nationwide database of current trend of helicobacter pylori eradication in Korea: interim analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:1246–1253. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.8.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gong EJ, Yun SC, Jung HY, Lim H, Choi K-S, Ahn JY, Lee JH, Kim DH, Choi KD, Song HJ, et al. Meta-analysis of first-line triple therapy for helicobacter pylori eradication in Korea: is it time to change? J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:704–713. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.5.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Ahn JY, Choi KD, Jung H-Y, Kim JM, Baik GH, Kim B-W, Park JC, Jung H-K, Cho SJ, et al. Nationwide antibiotic resistance mapping of Helicobacter pylori in Korea: a prospective multicenter study. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12592. doi: 10.1111/hel.12592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim N, Kim JM, Kim CH, Park YS, Lee DH, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Institutional difference of antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains in Korea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(8):683–687. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang X, Xu X, Zheng Q, Zhang W, Sun Q, Liu W, Xiao S, Lu H. Efficacy of bismuth-containing quadruple therapies for clarithromycin-, metronidazole-, and fluoroquinolone-resistant Helicobacter pylori infections in a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(802–7.e1). doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choe JW, Jung SW, Kim SY, Hyun JJ, Jung YK, Koo JS, Yim HJ, Lee SW. Comparative study of Helicobacter pylori eradication rates of concomitant therapy vs modified quadruple therapy comprising proton-pump inhibitor, bismuth, amoxicillin, and metronidazole in Korea. Helicobacter. 2018;23(2):e12466. doi: 10.1111/hel.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salmanroghani H, Mirvakili M, Baghbanian M, Salmanroghani R, Sanati G, Yazdian P. Efficacy and tolerability of two quadruple regimens: bismuth, omeprazole, metronidazole with amoxicillin or tetracycline as first-line treatment for eradication of helicobacter pylori in patients with duodenal ulcer: a randomized clinical trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0197096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, Chen Q, Liang X, Liu W, Xiao S, Graham DY, Lu H. Bismuth, lansoprazole, amoxicillin and metronidazole or clarithromycin as first-line Helicobacter pylori therapy. Gut. 2015;64(11):1715–1720. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Q, Zhang W, Fu Q, Liang X, Liu W, Xiao S, Lu H. Rescue therapy for helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized non-inferiority trial of amoxicillin or tetracycline in Bismuth quadruple therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1736–1742. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim H, Bang CS, Shin WG, Choi JH, Soh JS, Kang HS, Yang YJ, Hong JT, Shin SP, Suk KT, et al. Modified quadruple therapy versus bismuth-containing quadruple therapy in first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea; rationale and design of an open-label, multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(46):e13245. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards . Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; seventeenth informational supplement. [accessed 2018 September13]. http://www.microbiolab-bg.com/CLSI.pdf.

- 19.Chung J-W, Lee JH, Jung H-Y, Yun S-C, Oh T-H, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Kim J-H. Second-line Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized comparison of 1-week or 2-week bismuth-containing quadruple therapy. Helicobacter. 2011;16(4):289–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alkim H, Koksal AR, Boga S, Sen I, Alkim C. Role of Bismuth in the eradication of helicobacter pylori. Am J Ther. 2017;24:e751–e757. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus EA, Sachs G, Scott DR. Colloidal bismuth subcitrate impedes proton entry into Helicobacter pylori and increases the efficacy of growth-dependent antibiotics. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:922–933. doi: 10.1111/apt.13346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham DY, Lee SY. How to effectively use Bismuth quadruple therapy: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2015;44:537–563. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugimoto M, Shirai N, Nishino M, Kodaira C, Uotani T, Yamade M, Sahara S, Ichikawa H, Sugimoto K, Miyajima H, et al. Rabeprazole 10 mg q.d.s. decreases 24-h intragastric acidity significantly more than rabeprazole 20 mg b.d. or 40 mg o.m., overcoming CYP2C19 genotype. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:627–634. doi: 10.1111/apt.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott DR, Sachs G, Marcus EA. The role of acid inhibition in Helicobacter pylori eradication. F1000Res. 2016;5:pii: F1000 Faculty Rev-1747. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8598.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murakami K, Sakurai Y, Shiino M, Funao N, Nishimura A, Asaka M. Vonoprazan, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, as a component of first-line and second-line triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a phase III, randomised, double-blind study. Gut. 2016;65(9):1439–1446. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2010;59:1143–1153. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.192757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van der Wouden EJ, Thijs JC, Zwet AA. The influence of metronidazole resistance on the efficacy of ranitidine bismuth citrate triple therapy regimens for Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:297–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chi CH, Lin CY, Sheu BS, Yang H-B, Huang A-H, Wu -J-J. Quadruple therapy containing amoxicillin and tetracycline is an effective regimen to rescue failed triple therapy by overcoming the antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:347–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uygun A, Ozel AM, Yildiz O, Aslan M, Yesilova Z, Erdil A, Bagci S, Gunhan O. Comparison of three different second-line quadruple therapies including bismuth subcitrate in Turkish patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia who failed to eradicate Helicobacter pylori with a 14-day standard first-line therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:42–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu L, Luo L, Long X, Liang X, Ji Y, Graham DY, Lu H. High-dose PPI-amoxicillin dual therapy with or without bismuth for first-line Helicobacter pylori therapy: A randomized trial. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12596. doi: 10.1111/hel.12596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo L, Ji Y, Yu L, Huang Y, Liang X, Graham DY, Lu H. 14-day high-dose amoxicillin- and metronidazole-containing triple therapy with or without Bismuth as first-line helicobacter pylori treatment. Dig Dis Sci. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwack W, Lim Y, Lim C, Graham DY. High dose ilaprazole/amoxicillin as first-line regimen for helicobacter pylori infection in Korea. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:1648047. doi: 10.1155/2016/1648047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park HY, Kang EJ, Kim DG, Kim KJ, Choi JW, Nam SY, Kwon YH, Lee HS, Jeon SW. High and frequent dose of dexlansoprazole and amoxicillin dual therapy for helicobacter pylori infections: a single arm prospective study. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2017;70:176–180. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2017.70.4.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bang CS, Kim YS, Park SH, Kim JB, Baik GH, Suk KT, Yoon JH, Kim DJ. Additive effect of pronase on the eradication rate of first-line therapy for helicobacter pylori infection. Gut Liver. 2015;9(3):340–345. doi: 10.5009/gnl13399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Eidan FA, McElnay JC, Scott MG, McConnell JB. Management of Helicobacter pylori eradication - the influence of structured counselling and follow-up. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:163–171. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arslan N, Yilmaz O, Demiray-Gurbuz E. Importance of antimicrobial susceptibility testing for the management of eradication in Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2854–2869. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i16.2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards . Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; seventeenth informational supplement. [accessed 2018 September13]. http://www.microbiolab-bg.com/CLSI.pdf.