ABSTRACT

Background

Animal data suggest a role of the gut-liver axis in progression of alcoholic liver disease (ALD), but human data are scarce especially for early disease stages.

Methods

We included patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD) who follow a rehabilitation program and matched healthy controls. We determined intestinal epithelial and vascular permeability (IP) (using urinary excretion of 51Cr-EDTA, fecal albumin content, and immunohistochemistry in distal duodenal biopsies), epithelial damage (histology, serum iFABP, and intestinal gene expression), and microbial translocation (Gram – and Gram + serum markers by ELISA). Duodenal mucosa-associated microbiota and fecal microbiota were analyzed by 16 S rRNA sequencing. ALD was staged by Fibroscan® (liver stiffness, controlled attenuation parameter) in combination with serum AST, ALT, and CK18-M65.

Results

Only a subset of AUD patients had increased 51Cr-EDTA and fecal albumin together with disrupted tight junctions and vasculature expression of plasmalemma Vesicle-Associated Protein-1. The so-defined increased intestinal permeability was not related to changes of the duodenal microbiota or alterations of the intestinal epithelium but associated with compositional changes of the fecal microbiota. Leaky gut alone did not explain increased microbial translocation in AUD patients. By contrast, duodenal dysbiosis with a dominance shift toward specific potential pathogenic bacteria genera (Streptococcus, Shuttleworthia, Rothia), increased IP and elevated markers of microbial translocation characterized AUD patients with progressive ALD (steato-hepatitis, steato-fibrosis).

Conclusion

Progressive ALD already at early disease stages is associated with duodenal mucosa-associated dysbiosis and elevated microbial translocation. Surprisingly, such modifications were not linked with increased IP. Rather, increased IP appears related to fecal microbiota dysbiosis.

KEYWORDS: Alcohol, liver disease, dysbiosis, microbiota, gut barrier, microbial translocation, CK-18, alcohol use disorder, alcohol abstinence

Introduction

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is one of the leading causes of chronic liver disease worldwide. Although around 90% of patients with alcohol use disorders (AUD) develop steatosis, only a minority progress to the more severe forms of liver disease and its related complications. Currently, the main mechanisms involved in disease progression are not completely understood1.

Animal models of chronic alcohol exposure highlight the potential role of the gut-liver axis in ALD evolution.2 Changes of the gut microbiota composition,3,4 disruption of the gut barrier function,5,6 and subsequent translocation of microbial products to the liver could activate immune responses implicated in disease progression.7 Manipulations designed to interfere with this process, all improved liver disease in animals.8–12 However, these data cannot necessarily be extrapolated to human pathology for several reasons. Animals have a natural aversion to alcohol,13,14 a 5 times faster ethanol metabolism,15 and profound differences in their immune system16 and their microbiota17 compared to humans. Animals do only develop mild forms of ALD upon chronic alcohol feeding and do not resume the liver-damage pattern observed in humans.18 Human studies generally focused on the role of the gut-liver axis in severe alcoholic hepatitis and decompensated cirrhosis.19–23 Little is known about the mechanisms operating at earlier stages of ALD and only two studies reported increased intestinal permeability (IP) in association with alterations of the fecal microbiota in less than 50% of AUD patients.24,25 Liver disease was not assessed in these reports.

The aim of our present study is to assess the relationship between IP, the duodenal and fecal microbiome, and microbial translocation in AUD patients and how these changes are associated with liver disease. To test this, we analyzed epithelial and vascular permeability, microbial translocation markers, and the composition of the microbiota attached to the duodenal mucosa and in the stools of actively drinking AUD patients. We finally correlated the observed changes with the pattern of liver disease.

Methods

Patients

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) patients (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria) admitted for elective alcohol withdrawal from April 2017 until January 2019 to dedicative alcohol withdrawal unit followed a highly standardized and controlled 3-week detoxification and rehabilitation program (Figure 1). They were compared to healthy volunteers matched for gender, age, and BMI (social drinkers consuming <20 g of alcohol/day) in a one(controls) to four (AUD patients) ratio. All patients reported long-term (>1 year) alcohol consumption (>60 g/day) and were actively drinking until the day of admission. Additional inclusion and exclusion criteria are available in Supplementary data. All clinical and baseline biochemical data were collected prospectively for all patients, and due to methodological and logistical reasons, the different investigations analysis were performed only in representative cohorts of patients, as indicated in the figure legends.

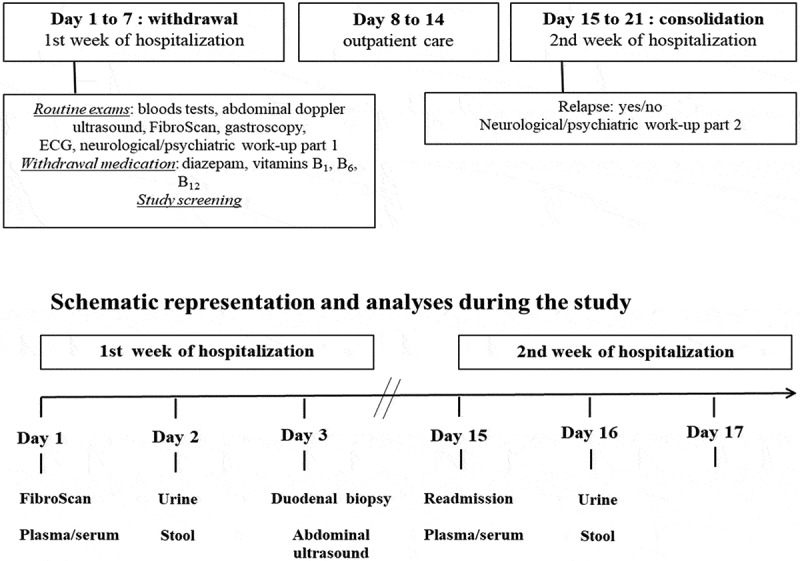

Figure 1.

Standardized working scheme of the alcohol withdrawal unit.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) patients are undergoing a highly standardized clinical work-up with fixed sampling of biological specimens.

Examinations and sample collections (Figure 1)

On the day of admission, Fibroscan® (Echosense, Paris, France) combined with the controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) were performed and a fasting blood sample (serum, plasma) was drawn. A 24 h urine collection for 51Cr-EDTA determination (see below) was obtained on the second day and a gastroscopy with distal duodenal biopsies on the following day (details in supplementary material). Stools samples were collected from the first bowel movement after admission.

In addition, patients underwent an abdominal Doppler ultrasound on the third day as part of the routine work-up in the unit.

Ethical aspects

The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institution’s human research and ethical committee (B403201422657). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and healthy volunteers. We followed the STROBE criteria for reporting cohort studies.

Measurement of intestinal permeability (IP) and intestinal epithelial cell damage

IP was assessed by measuring the urinary excretion of the radioactive probe 51Cr-EDTA, as described previously24 and the fecal albumin content using a commercial ELISA kit (Human Albumin ELISA Kit, Immundiagnostik AG, Bensheim, Germany) (details in supplementary material).

Intestinal epithelial cell damage was measured by ELISA using serum intestinal fatty acid-binding protein (i-FABP) as a surrogate marker following the manufacturer’s instructions (Human i-FABP ELISA kit, HycultBiotech, Uden, Holland).

Histology and morphometric indices

Duodenal sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin and examined by an experienced gastro-intestinal pathologist as a part of the standardized routine procedure of the alcohol withdrawal unit. Slides were then digitalized using a SCN400 slide scanner (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) at X20 magnification and subjected to morphometric analysis. The major axis length of several villi was measured (details in supplementary material).

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin fixed duodenal sections were routinely stained and analyzed by immunohistochemistry using standard methods followed by quantification (details in supplementary material).

Immunofluorescence

Five µm cryosections were stained with the primary and secondary antibodies followed by quantification (details in supplementary material).

16 S rRNA sequencing and data analysis

DNA extraction and 16 S rRNA library were constructed as described previously.26 16 S sequence reads were processed using MOTHUR-base 16 S analysis workflow to determine the operational taxonomic units as described previously.11,27,28 Phyloseq package was used for the α-diversity (observed OTUs, Chao 1, Shannon, and Simpson) and β-diversity (weighted and unweighted Unifrac) analysis.29 Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) was used to compare the difference between different groups.30

Determination of serum biomarkers of liver cell damage and microbial translocation

In addition to AST and ALT, serum cytokeratin 18 (CK18) was used to assess liver cell damage (CK18-M65 ELISA kit; TECOmedical AG, Sissach, Switzerland). Microbial translocation was determined using soluble CD14, Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein (Human CD14 Quantikine ELISA kit sCD14 and Human LBP duoset ELISA, Bio-techne Ltd., Abingdon, United Kingdom) and Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins (Human PGRPs ELISA kit, Thermofisher, Merelbeke, Belgium), respectively. All assays were performed in duplicate following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Reverse-transcription and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Duodenal tissue messenger RNA (mRNA) was assessed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantified as described.31 Primer sequences are listed in supplementary material.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using Graph Pad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise indicated. Normality was assessed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test followed by t-tests for normally distributed data, or the Wilcoxon test for nonnormally distributed data. Data were compared by one-way ANOVA for multiple groups, followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons. Wilcoxon or paired t-tests compared data of patients before and after abstinence. Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation tests were used for correlations between data sets. A p value <.05 was considered as statistically significant. Area under the receiver-operating characteristics curves (AUROC) were constructed using the method by Hanley and McNeil. Youden’s statistics was performed for the determination of the threshold values. MaAsLin2 analysis (https://bitbucket.org/biobakery/maaslin2/src/default/) was used to determine the association between microbiota and serum surrogate markers of microbial translocation.

Results

Study population

The study population consists of a cohort of 106, middle-aged, predominantly male AUD patients and 24 volunteers. Demographic and biochemical data are provided in Table 1. All patients reported alcohol consumption until the evening prior to their admission. Twenty-seven percent (29/106) had detectable blood alcohol concentrations on the following day at admission with a median level of 0.5 g/L (range 0.1–2.5 g/L).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and biochemical data of the study population.

|

Demographics |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy volunteers (n = 24) |

AUD patients (n = 106) |

p value | |||

| Gender (female/male) | 10 (41.6%)/14 (58.4%) | 28 (26.4%)/78 (73.6%) | .1380 | ||

| Mean ± SEM | |||||

| Age (years) | 42 ± 11 | 46 ± 9.2 | .1537 | ||

| Height (m) | 1.74 ± 0.08 | 1.75 ± 0.07 | .9583 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 71.4 ± 9.4 | 75 ± 11.3 | .2598 | ||

| BMI | 23.4 ± 2.9 | 24.6 ± 3.2 | .2012 | ||

| Biochemistry | |||||

| Mean ± SEM (normal range) | |||||

| AST (IU/L) | 17.8 ± 3.5 | 64 ± 44.4 (<40) | .0274 | ||

| ALT (IU/L) | 10.9 ± 2.9 | 53.5 ± 34.6 (<40) | .0052 | ||

| γ-GT (IU/L) | 22.4 ± 8.6 | 211.4 ± 217.6 (<40) | .1745 | ||

| ALP (IU/L) | 52 ± 11 | 79 ± 24 (30–120) | .0578 | ||

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.21 ± 0.13 | 0.55 ± 0.24 (0.3–1.2) | .0106 | ||

| Albumin (g/L) | 44 ± 0.8 | 47 ± 4 (35–52) | .0717 | ||

| Creatinine | 0.97 ± 0.13 | 0.8 ± 0.1 (<1.2) | .0021 | ||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; AST, Aspartate transaminase; ALT, Alanine transaminase; γ-GT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase

Clinical classification of patients according to severity of liver disease

To allow a more detailed analysis related to clinical parameters we assessed the pattern of liver disease in AUD patients who were clinically classified as depicted in Table 2 into non-progressive (no liver disease/simple steatosis) and progressive liver disease (steato-hepatitis/steato-fibrosis). All the patients with steato-hepatitis or steato-fibrosis had a preserved synthetic liver function and showed no clinical signs of liver decompensation. Doppler ultrasound ruled out any significant vascular or biliary problem in the liver.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the patient’s subgroups based on clinical evaluation of ALD.

| |

Non-progressive liver disease (n = 53) |

Progressive liver disease (n = 45) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No liver disease (n = 24) | Simple steatosis (n = 29) | Steato-hepatitis (n = 29) | Steato-fibrosis (n = 16) | |

| Clinical parameters | AST/ALT < 40 IU/L | AST/ALT < 40 IU/L | AST/ALT > 40 IU/L | AST/ALT > 40 IU/L |

| CAP < 250 dB/m | CAP > 250 dB/m | CAP > 250 dB/m | CAP > 250 dB/m | |

| kPa < 7.6 | kPa < 7.6 | kPa < 7.6 | kPa > 7.6 | |

| Clinical data | ||||

| AST (IU/L; N < 40) | 22.16 ± 4.68 | 28.93 ± 5.73 | 89.78 ± 34.24 | 127.125 ± 89.05 |

| ALT (IU/L; N < 40) | 19.21 ± 5.17 | 27.76 ± 9.13 | 84.57 ± 30.37 | 88.44 ± 55.99 |

| γ-GT (IU/L; N < 40) | 35.3 ± 18.48 | 68.48 ± 41.32 | 217.25 ± 151.62 | 521 ± 372.87 |

| ALP (IU/L; N < 130) | 61.74 ± 10.88 | 68.82 ± 15.25 | 76.25 ± 14.82 | 111.69 ± 35.77 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL; N < 1.2) | 0.46 ± 0.18 | 0.48 ± 0.18 | 0.51 ± 0.14 | 0.76 ± 0.44 |

| Albumin (g/L; N > 35) | 47.46 ± 3.36 | 47.64 ± 2.95 | 47.99 ± 3.68 | 45.67 ± 6.25 |

| CAP (dB/m) | 202 ± 22 | 297 ± 29 | 319 ± 24 | 296 ± 45 |

| kPa | 4.85 ± 0.81 | 4.79 ± 0.95 | 5.53 ± 0.92 | 20.69 ± 12.06 |

Serum cytokeratin 18 levels (CK18) further refine the clinical classification

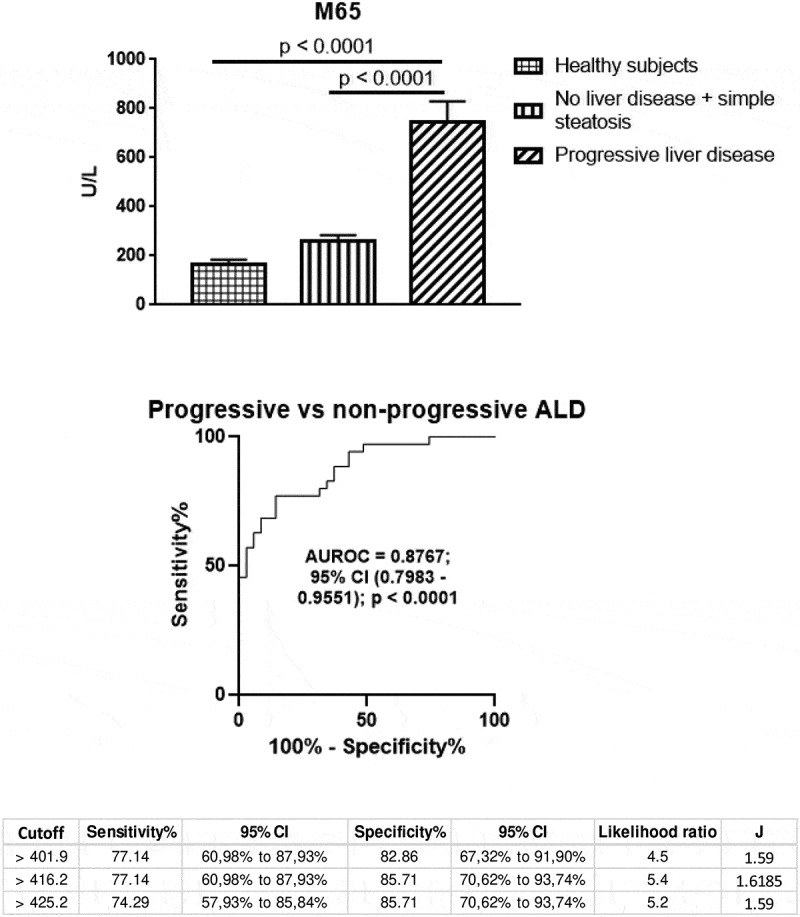

Cytokeratin 18 is released upon cell damage (necrosis, apoptosis) and has been considered as a liver-specific cell damage marker.32 Serum CK18-M65 increased significantly in AUD patients compared to healthy volunteers. When looking at the different clinical subgroups, high CK-M65 levels were found in AUD patients with progressive ALD but not in those with non-progressive forms of the disease (Figure 2). Receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis showed that serum CK18-M65 levels allowed to distinguish with high accuracy progressive ALD from the non-progressive forms of liver disease (AUROC = 0.8767; 95%CI: 0.7983–0.9551; p < .0001). We then identified the cutoff using the Youden’s statistics (416 U/L) with the best specificity and sensitivity profile (85.7% and 77.1%, respectively). Interestingly, CK18-M65 levels did not separate patients with steato-hepatitis from those with steato-fibrosis within the progressive ALD group (Supplementary Figure 1). Thus, CK18-M65 was associated with liver damage regardless of fibrosis.

Figure 2.

Serum cytokeratin 18 (CK18-M65) as a surrogate marker of liver damage.

High serum CK18-M65 levels characterized progressive ALD (upper) and differentiate severe forms of alcoholic liver disease from the non-progressive forms of alcoholic liver disease, as shown by Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis (middle) (AUROC = 0.8767; 95% CI: 0.7983–0.9551; p < .0001). Below, the cutoff identified using the Youden’s statistics (416.2 U/L) was characterized by high sensitivity and specificity (77.14% and 85.71%, respectively).

Overall, serum CK18-M65 seems to be a reliable diagnostic tool to identify progressive ALD with a high positive likelihood ratio (Table 3). Consequently, we used CK to adjust the definition of the group with no liver disease or steatosis (CK18 < 416 U/L, G1 group) and the group with steato-hepatitis or steato-fibrosis (CK>416 U/L, G2 group).

Table 3.

Statistical analysis of serum CK18-M65 levels as a biomarker of progressive ALD.

| Statistics | Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Likelihood Ratio | 5.56 | 2.43 to 12.74 |

| Negative Likelihood Ratio | 0.24 | 0.12 to 0.47 |

| Positive Predictive Value (%) | 84.37 | 70.20 to 92.52 |

| Negative Predictive Value (%) | 81.08 | 68.60 to 89.37 |

| Accuracy (%) | 82.61 | 71.59 to 90.68 |

Assessment of intestinal permeability (IP), morphology and microbial translocation in AUD patients

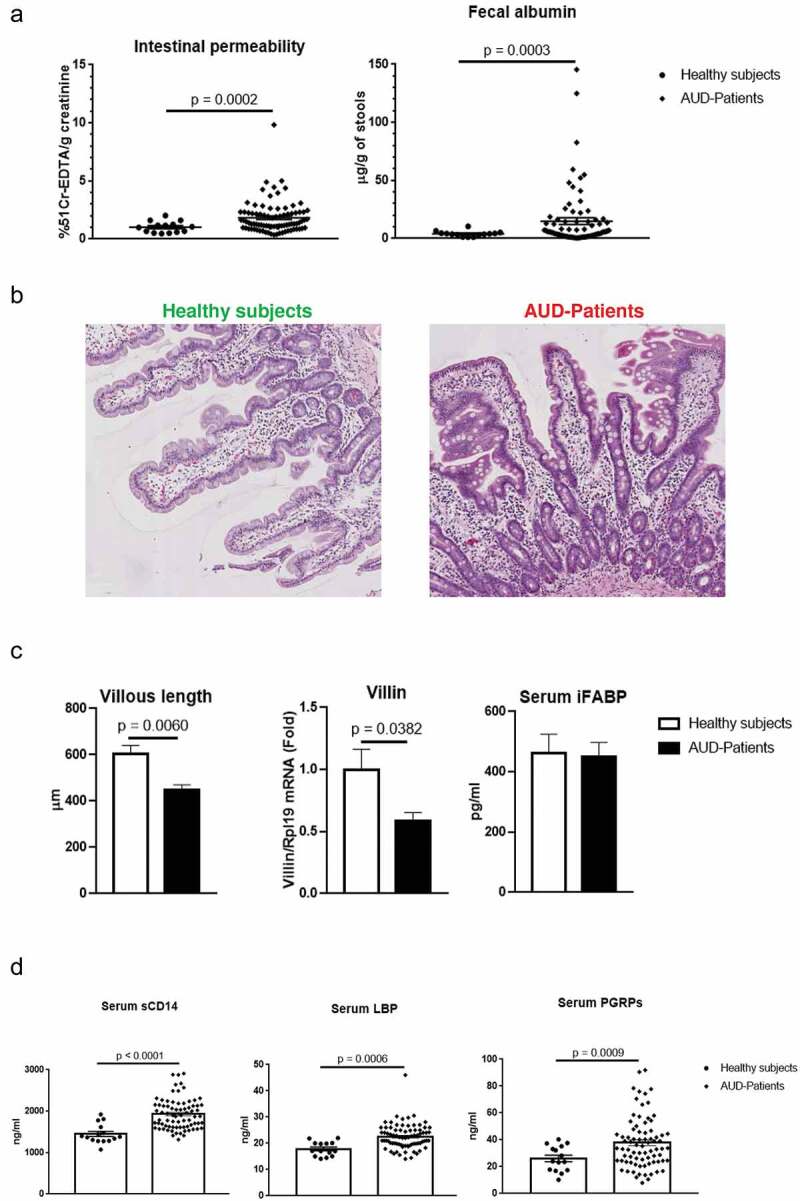

Intestinal paracellular and capillary leakiness33 can be measured by the urinary excretion of the radioactive probe 51Cr-EDTA and fecal albumin content, respectively. Compared to controls, 51Cr-EDTA and fecal albumin content supported increased IP in actively drinking AUD (Figure 3a). The two markers were however not correlated (r = 0.006, p = .9625) meaning that they likely do not measure the same parameters of IP.33 In addition, immunofluorescence showed up-regulated duodenal expression of plasmalemma Vesicle-Associated Protein 1(PV-1), a marker of disruption of the Gut-Vascular Barrier34 in AUD patients compared to controls (Figure 4c).

Figure 3.

Assessment of intestinal permeability (IP), morphological features of the duodenal mucosa, enterocyte damage and microbial translocation.

(a) IP measured in vivo by 51Cr-EDTA (n = 86) urinary excretion (left) and fecal albumin content (n = 78) (right) increased significantly in the overall alcohol use disorder (AUD) population compared to controls (n = 14). (b) Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of duodenal biopsies from healthy volunteers and AUD patients. (c) Morphometric analysis showing statistically significant reduction of villi’s length in AUD patients (n = 11) compared to controls (n = 5) associated with down-regulation of Villin gene expression by qPCR (middle) in AUD patients (n = 43) compared to controls (n = 9) whereas serum levels of the enterocyte damage marker (intestinal fatty acid binding protein, i-FABP) (right) did not differ between AUD patients (n = 77) and healthy subjects (n = 11). (d) Gram-negative soluble CD14 (sCD14) and Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein (LBP) as well as the Gram-positive translocation marker Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins (PGRPs) increased significantly in AUD patients (n = 75) compared to controls (n = 15).

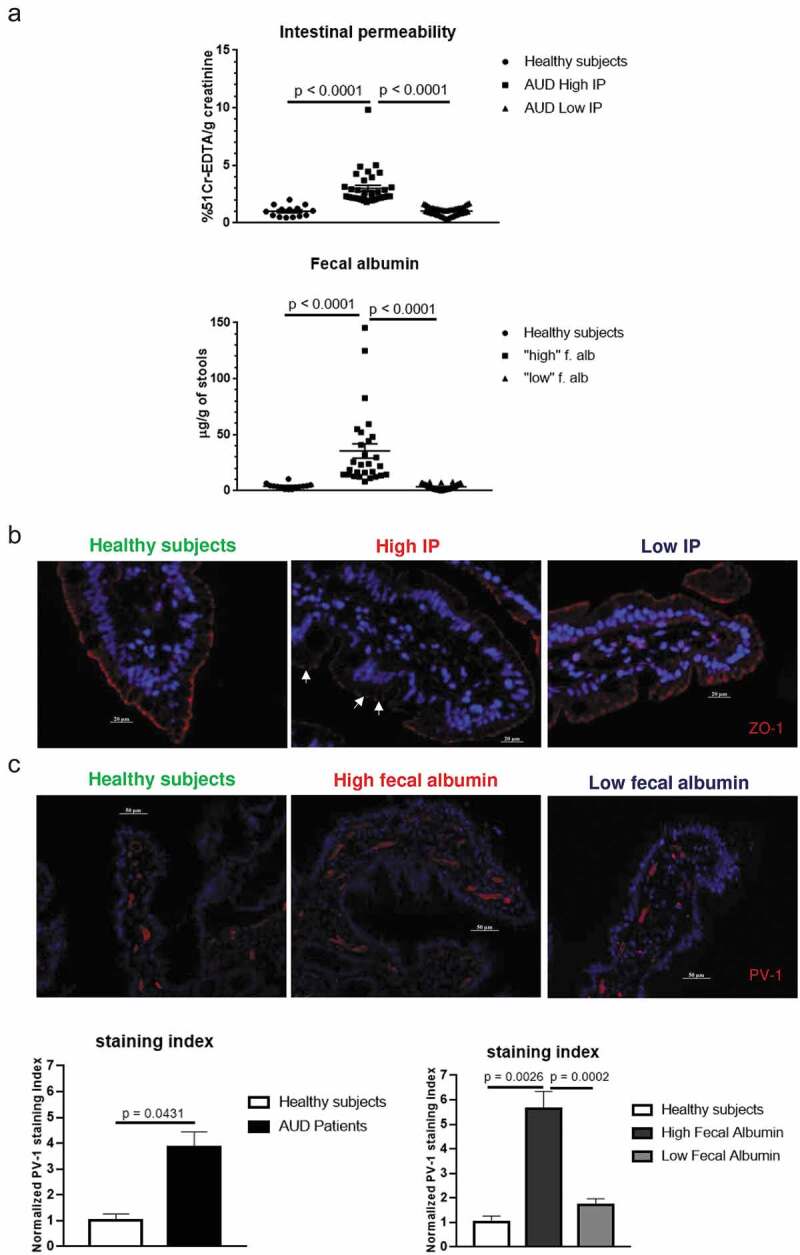

Figure 4.

Assessment of intestinal permeability (IP) in relation to histological features.

(a) More detailed analysis revealed that only one-third of AUD patients showed significantly increased IP (n = 34 and n = 28 for 51Cr-EDTA and fecal albumin, respectively) compared to controls. This separation of subjects was calculated according to a deviance criterion at a threshold of 1.65 SDs of the mean of the control group. (b) Representative immunofluorescence of ZO-1 duodenal tissues from healthy volunteers, and AUD patients with high IP and low IP showing disrupted tight junctions (indicated by arrows) in AUD patients only with high IP. (c) Representative immunofluorescence staining of PV-1 in duodenal tissues of healthy volunteers and AUD patients with high and low fecal albumin, respectively. Increased expression PV-1 in vessels of AUD patients was found principally in association with high fecal albumin and confirmed by quantitative analysis (staining index).

As morphological changes and/or enterocyte damage might be causes of gut barrier dysfunction, we studied mucosal morphology on duodenal biopsies and measured serum i-FABP levels as a marker of intestinal epithelial cell damage. Compared to healthy volunteers, AUD patients were characterized by shorter villi and down-regulation of Villin gene expression (Figure 3b, c). Serum i-FABP did not significantly change between AUD patients and controls (Figure 3c)

Soluble CD14 (sCD14), lipopolysaccharide binding protein (LBP) and Peptidoglycan-recognition Proteins (PGRPs) have been used as serum surrogate markers of microbial translocation (MT) for Gram- and Gram+ bacteria, respectively.35–37 All three markers were significantly higher in AUD patients compared to healthy controls (Figure 3d). Chronic alcohol consumption has also been associated with an altered mycobiome and translocation of fungal products.20 We thus assessed serum antibodies directed against Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ASCA) as a potential surrogate of fungal translocation. Serum ASCA IgA and IgG were low or undetectable in controls whereas high levels were observed in AUD patients (Supplementary Figure 4).

Only a subset of AUD patients shows increased IP together with disruption of tight junctions and vasculature expression of PV-1

When looking at the data more closely, about two-thirds of AUD patients had intestinal permeability measurements close to those of controls while 36–40% showed high IP based on fecal albumin and 51Cr-EDTA, respectively (Figure 4a). This separation of subjects into two categories was calculated according to a deviance criterion at a threshold of 1.65 SDs of the mean of the control group. High IP was principally related to the proximal small bowel as suggested by the small bowel component (duodenum, jejunum) of the 51Cr-EDTA measurements (Supplementary Figure 2) without significant modifications of the distal gut component (ileum, colon) (data not shown).

In accordance with 51Cr-EDTA data, Zonula Occludens 1 (ZO-1), a tight junction protein that regulates paracellular permeability, was disrupted in AUD subjects with high IP but not in those with normal IP (Figure 4b). By contrast, patients with high fecal albumin content showed a higher staining index of PV-1 in endothelial cells of the duodenal mucosa (Figure 4c).

Morphological changes or enterocyte damage do not associate with intestinal permeability

Strikingly, morphological changes were not more prominent in AUD patients with high IP (Supplementary Figure 3) suggesting that they do not play a major role in determining intestinal permeability. Increased IP was not associated with enterocyte damage since even after splitting them according to permeability measurements no differences in serum i-FABP were found compared to controls (Supplementary Figure 3).

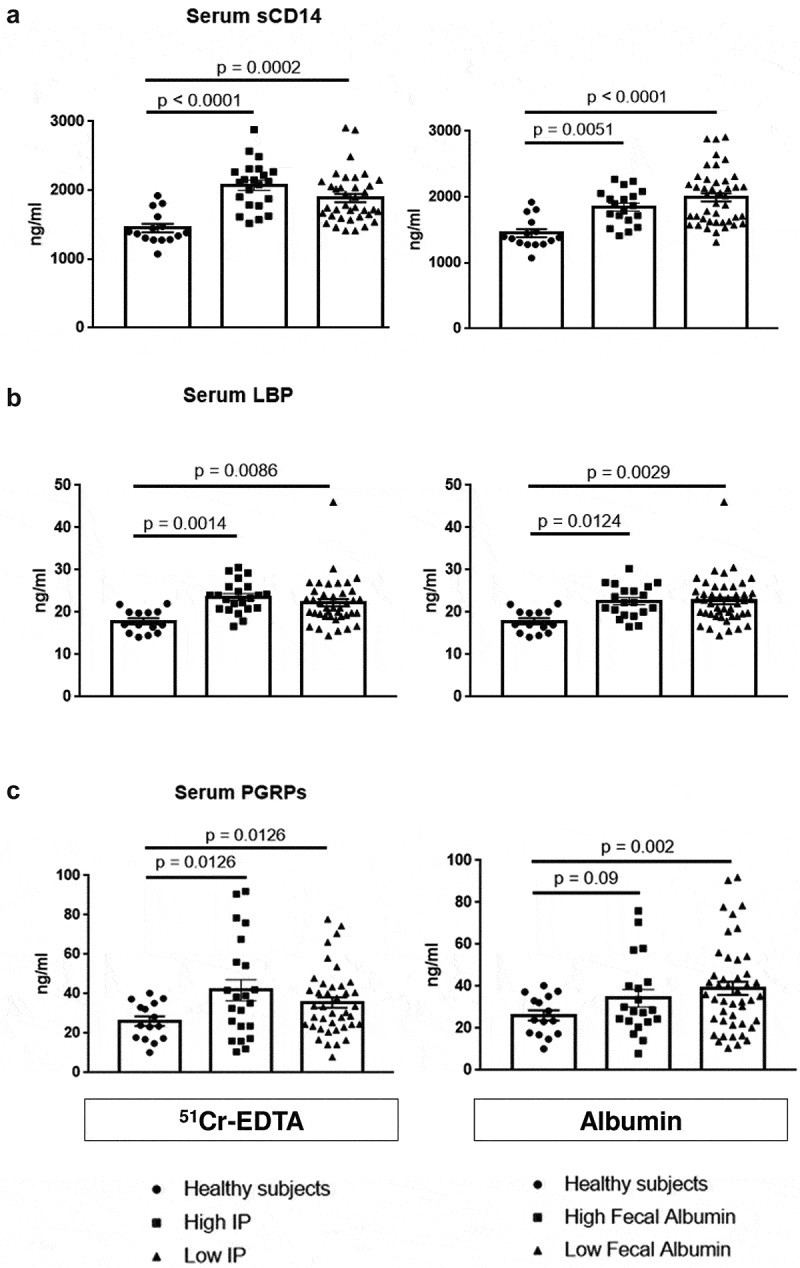

Microbial translocation is not exclusively dependent on increased IP

Serum surrogate markers of microbial translocation (PGRPs, sCD14, and LBP) were significantly higher in AUD patients compared to healthy controls. However, the levels were similar in the patients with increased and normal gut permeability whether based on 51Cr-EDTA or fecal albumin measurements (Figure 5a–c). As with bacterial translocation markers, an increase in ASCA levels in AUD patients occurred independently from high IP and high fecal albumin (Supplementary Figure 4).

Figure 5.

Assessment of serum microbial translocation markers in relation to intestinal permeability (IP).

Gram-negative (a, b) soluble CD14 (sCD14) and Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein (LBP) as well as the Gram-positive translocation marker (c) Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins (PGRPs) increased significantly in AUD patients with high and low IP compared to controls while levels did not differ between high and low IP, measured by 51Cr-EDTA urinary excretion (left graphs) and fecal albumin content (right graphs).

These observations suggest that, in AUD patients, systemic microbial translocation might occur even if IP is normal.

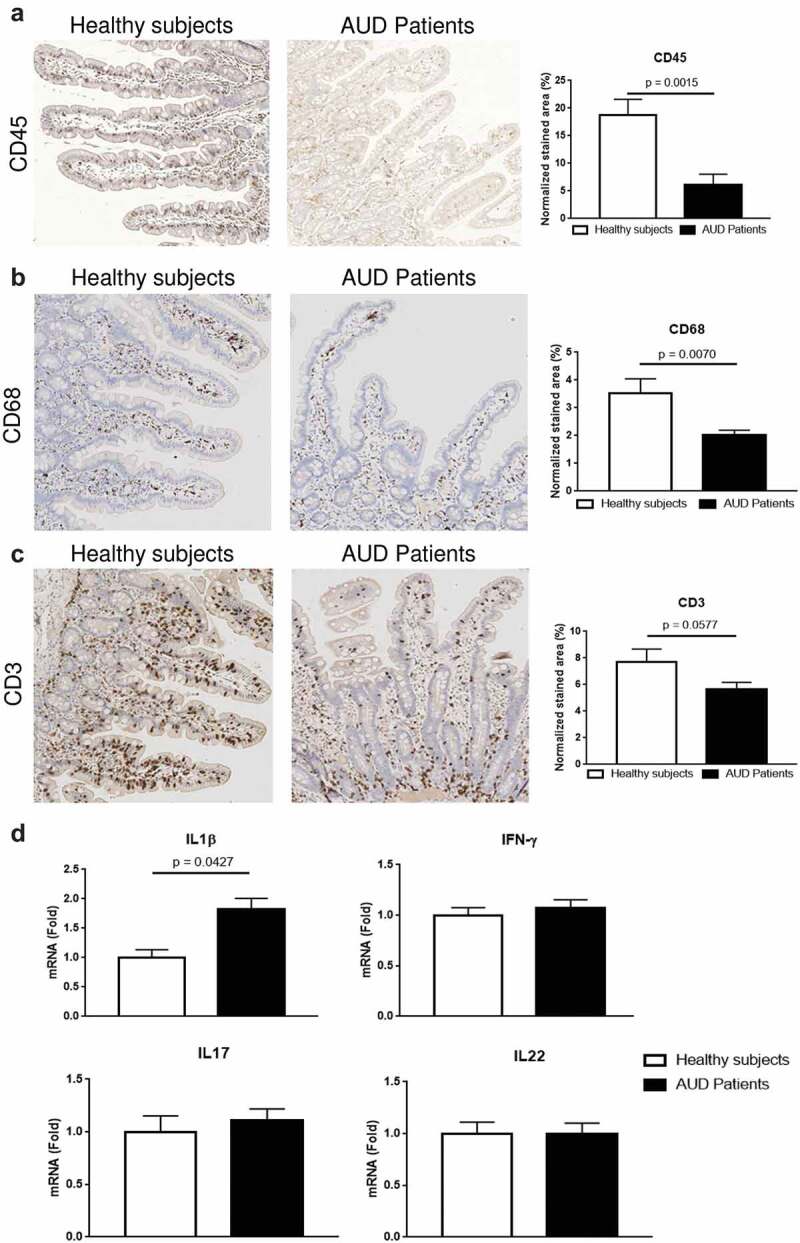

Reduced inflammatory cell infiltration and absence of a pro-inflammatory response characterized the duodenal mucosa of AUD patients

Since intestinal inflammation could contribute to intestinal cell damage and favor microbial translocation, we quantified duodenal mucosal infiltration by immune cells and assessed mucosal expression of major gut-specific pro-inflammatory cytokines. Overall, CD45-positive immune cells and more specifically CD68-positive macrophages and CD3-positive T cells were reduced in distal duodenal biopsies in AUD patients (Figure 6a–c). Although Interleukin-1beta (IL1β) mRNA was increased, other gut-specific pro-inflammatory cytokines, interleukin 17 and 22 as well as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) remained unchanged in AUD patients compared to healthy controls (Figure 6d).

Figure 6.

Evaluation of immune cells and inflammatory markers in the duodenum of alcohol use disorder (AUD) patients.

Immunohistochemistry analysis of the hematopoietic cell marker CD45 (a) revealed a decrease of immune cells in the duodenal mucosa of AUD patients (n = 11) compared to controls (n = 6). Analysis of the macrophages marker CD68 (b) and the T cell marker CD3 (c) revealed a reduction of both cell types in the duodenal mucosa of alcohol use disorder (AUD) patients (n = 15) compared to healthy controls (n = 8). Duodenal gene expression (d) of Interleukin-1beta (IL1β) increased in AUD patients (n = 59) compared to controls (n = 13) while mRNA levels of Interleukin-17(IL17), Interleukin-22 (IL22) and Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) were similar between AUD patients and healthy volunteers.

These results rule out mucosal inflammation as a significant driver of morphological changes and microbial translocation in AUD patients. Rather a reduction of immune effector cells in the small gut might contribute to decreased immune surveillance and facilitate microbial translocation.

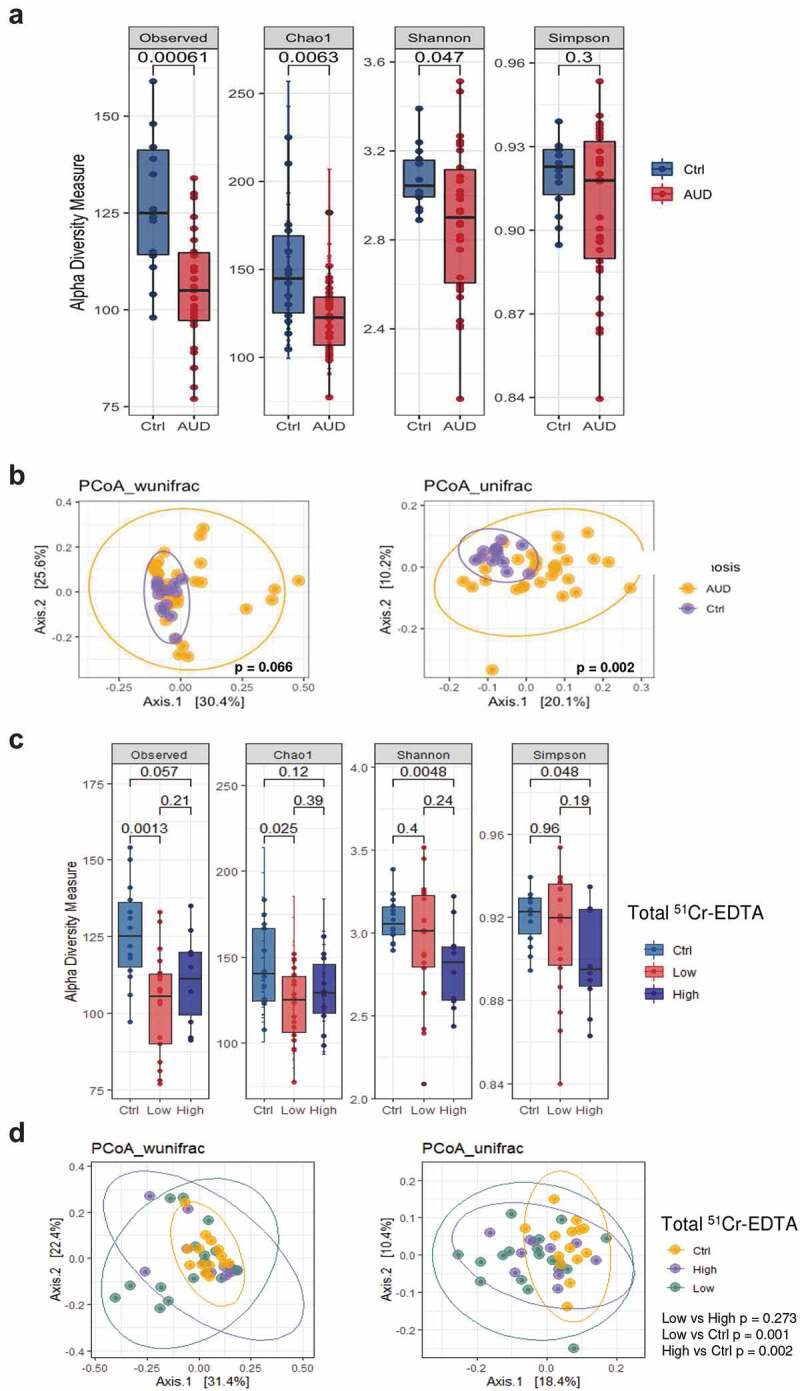

Assessment of the duodenal mucosa-associated microbiota and fecal microbiota in relation to IP

Changes in the duodenal mucosa-associated microbiota in AUD patients do not determine increased intestinal permeability

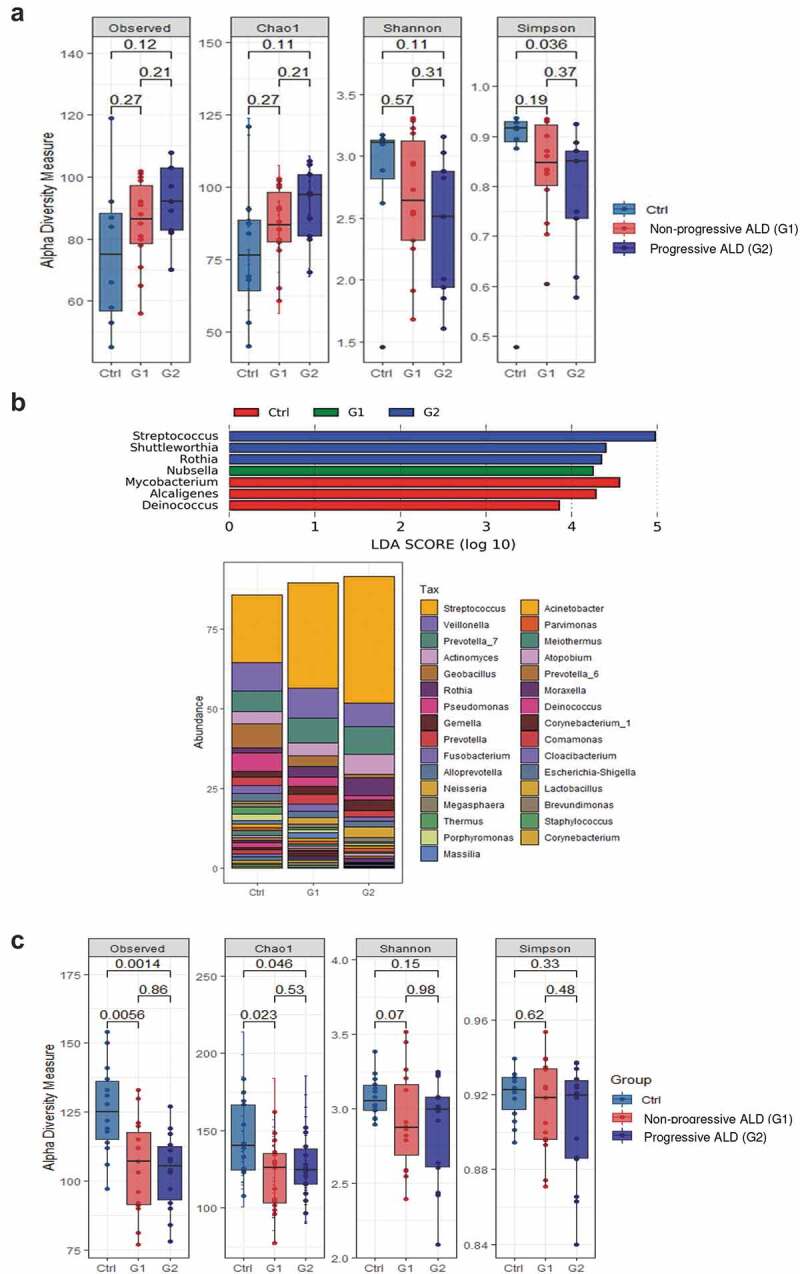

We have previously observed an increased number of duodenal mucosa-associated bacteria in AUD patients.9 We here analyzed the composition of the microbiota in duodenal biopsies of a representative group of actively drinking AUD patients. Albeit not-significant, duodenal-associated microbiota of AUD patients showed an increased number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) compared to healthy volunteers (Observed species and Chao1) reflecting a higher richness. Intriguingly, this increased number of bacteria was accompanied by a reduced Simpson index in AUD patients. This observation suggests that the different OTUs are not evenly distributed and indicates that some bacterial taxa are more dominant than others (Figure 7a). Although the PCoA of β-diversity indexes (weighted and unweighted Unifrac) did not allow a clear separation between AUD patients and healthy controls (Figure 7a), we found that 10 bacterial genera were different between AUD and controls. As reflected by the LDA score, the relative abundance of Nubsella, Rothia, and Streptococcus was higher in AUD patients while the relative abundance of Mycobacterium, Alcaligenes, Lachnoclostridium, Ralstonia, Rarobacter, Ethanoligenens, and Dolosigranulum was higher in healthy subjects (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Evaluation of duodenal mucosa-associated microbiota in relation to intestinal permeability (IP).

(a) Microbial α diversity (left), showed an increased number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (Observed and Chao1), in AUD patients (n = 22) compared to healthy volunteers (n = 8) indicating increased richness. This increased number of bacteria was accompanied by reduced evenness (Simpson index), with a shift regarding the dominance of certain genera, compared to controls. By contrast, β diversity (right) did not differ between AUD and controls. (b) Different genera overrepresented in the distal duodenum of AUD patients and healthy subjects, as assessed by linear discriminating analysis (LDA) (above) of AUD patients compared to controls at the genus level. Below, the relative abundance of the different genera in the two groups. Only genera with detection in at least 2% are shown. (c) No differences in terms of α diversity were found when AUD patients were split into high (n = 8) and low IP (n = 14), according to 51Cr-EDTA measurements.

We next assessed whether mucosa-associated microbiota changes were related to increased IP assessed by 51Cr-EDTA measurements. Despite the observed differences between AUD patients and healthy subjects, neither α-diversity indexes nor β-diversity did differ between AUD patients with high IP when compared to those with normal IP (Figure 7c, Supplementary Figure 5).

These observations suggest that changes in the duodenal microbiota do not necessarily associate with increased intestinal permeability.

Reduced richness and evenness of the fecal microbiota in AUD patients is associated with increased intestinal permeability

We assessed whether changes of the fecal microbiota were associated with leaky gut in our cohort of AUD patients. We compared the fecal microbiota of AUD patients and healthy controls. Microbial α-diversity indexes were lower in AUD patients, reflecting reduced richness (observed species, Chao1) and evenness (Shannon). This also indicates that the number of OTUs was lower and less evenly distributed in the fecal samples of AUD patients compared to controls. (Figure 8a). Furthermore, the PCoA of UniFrac indexes (β-diversity) allows a separation between the AUD patients and healthy subjects suggesting that bacterial profiles are different between these two groups (Figure 8b). Linear discriminating analysis (LDA) revealed a higher abundance of five genera such as Gemella, Actinomyces, Desulfovibrio, Subdoligranulum, and Akkermansia in AUD patients compared to healthy subjects (Supplementary Figure 6).

Figure 8.

Fecal microbiota assessment in AUD patients in relation to intestinal permeability (IP).

(a) Microbial α diversity showed reduced number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (Observed and Chao1), in AUD patients (n = 30) compared to healthy volunteers (n = 13) indicating reduced richness. Intriguingly, this diminished number of bacteria was accompanied by decreased evenness (Shannon index), reflecting the loss of rare species, compared to controls. (b) Comparison of principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) by using weighted and unweighted UniFrac distance showed that overall fecal microbiota composition (β diversity) was different between AUD patients and controls. Each dot represents one sample and the distance between the samples represents the difference in community composition of the samples. (c) Reduced evenness (Shannon and Simpson) were found only in AUD patients with high IP compared to controls. (d) Fecal microflora composition (β diversity) did not change between AUD patients with high and low IP.

Compared to controls, reduced richness, and evenness of the fecal microbiota were principally found in AUD patients with high but not in normal IP (Figure 8c). By contrast, bacterial composition (β-diversity) of the stool microflora were similar in high and low IP (Figure 8d, Supplementary Figure 7).

These observations suggest that compositional changes of the fecal microbiota could be associated with increased intestinal permeability.

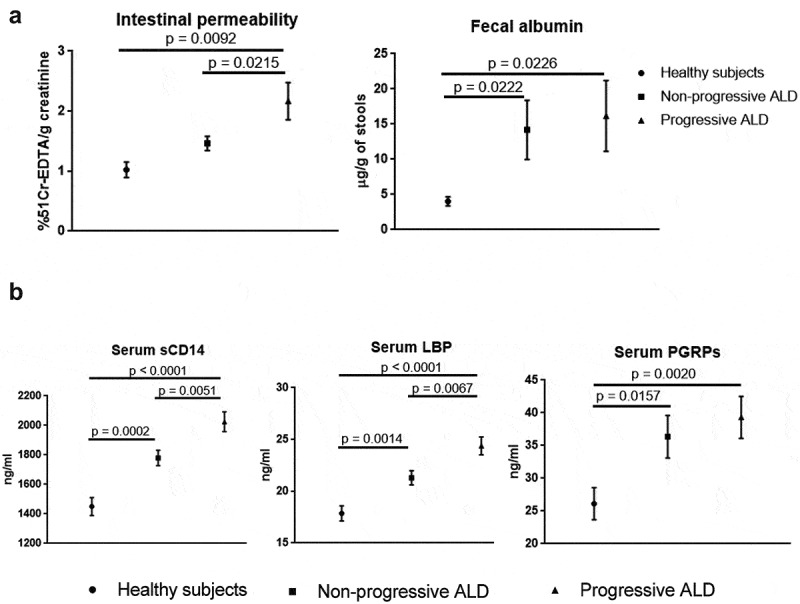

Relationship between progressive ALD, intestinal permeability, microbial translocation, and microbiota

Elevated translocation of microbial products has been linked in ALD models to the progression of liver disease.38,39 After refining of the clinical subgroups using CK18-M65 biomarker, we assessed whether IP, microbial translocation markers, duodenal, and fecal microbiota changes were associated with progressive forms of liver disease.

Increased IP and Gram-negative translocation markers are associated with progressive forms of liver disease

51Cr-EDTA increased significantly with progressive ALD compared to controls but no differences were found between non-progressive ALD and healthy volunteers. By contrast, fecal albumin increased independently of ALD severity (Figure 9a). Serum microbial Gram-negative markers sCD14 and LBP were upregulated in AUD patients with the highest levels found in progressive ALD (Figure 9b). Both markers also significantly correlated with CK18-M65 (r = 0.39 and 0.378; p < .001, respectively).

Figure 9.

Relationship between intestinal permeability (IP), microbial translocation and stage of alcoholic liver disease (ALD).

(a) IP assessed by 51Cr-EDTA (left) increased significantly with progressive ALD while levels in non-progressive ALD remained close to controls. High fecal albumin (right) was independent from liver disease severity and already significantly increased in non-progressive ALD compared to controls. (b) Gram-negative serum microbial translocation markers soluble CD14 (sCD14) and Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein (LBP) levels gradually increased with the highest levels observed in progressive ALD, while the Gram-positive translocation marker Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins (PGRPs) increased independently from the stage of ALD compared to controls.

By contrast, PGRPs rose independently of the stage of liver disease in AUD patients (Figure 9b) as did serum ASCA IgA and IgG (Supplementary Figure 8).

Increased richness and predominance shift in the duodenal mucosa-associated microbiota, but not in the fecal microbiota, in patients with progressive ALD

AUD patients with progressive ALD showed increased richness (observed species, Chao1) as well as reduced evenness with a dominance shift toward some bacterial taxa (Simpson) of their mucosa-associated microbiota whereas no significant changes were found in AUD with non-progressive liver disease compared to controls (Figure 10a). While the overall bacterial profiles (β-diversity) did not differ between the groups (Supplementary Figure 9a), we found that six OTUs were different between progressive ALD and controls. LDA scores indicated that Streptococcus, Shuttleworthia, and Rothia were overrepresented in AUD patients with progressive ALD while Mycobacterium, Alcaligenes, and Deinococcus were specific of healthy volunteers (Figure 10b).

Figure 10.

Analysis of the duodenal mucosa-associated microbiota and fecal microbiota in relation to alcoholic liver disease (ALD) severity.

(a) Microbial diversity (α diversity), plotted for healthy controls (Ctrl), AUD patients with non-progressive ALD (G1) and progressive ALD (G2), showed that G2 is characterized by increased richness as well as a reduced evenness with a shift in bacterial dominance (Simpson index) of their mucosa-associated microbiota compared to controls. (b) Different genera overrepresented in the distal duodenum of AUD patients in relation to ALD severity and healthy subjects (Ctrl). Results of linear discriminating analysis (LDA) of AUD patients (G1 and G2) compared to controls at the genus level. Below, relative abundance of the different genera in the three groups. Only genera with detection in at least 2% are shown. (c) By contrast to the duodenal mucosa-associated microbiota, fecal microbial α diversity did not differ in AUD patients when they were split according to the severity of liver disease.

We finally assessed whether dysbiosis of the fecal microbiota was also associated with progressive ALD. Interestingly, and in contrast to the duodenal microbiota, no differences in α- and β-diversity indexes and composition of the fecal microbiota were observed when the cohort was split into AUD patients with or without progressive liver disease compared to controls (Figure 10c, Supplementary Figure 9b).

Thus, increased richness with a dominance shift toward specific bacteria of the duodenal mucosa-associated microbiota and not of the fecal microbiota, are associated with progressive ALD.

Microbial translocation markers correlate with duodenal microbiota changes in progressive ALD

We next assessed the association between microbiota and two representative serum surrogate markers of microbial translocation (sCD14 and PGRPs). In patients with non-progressive ALD, six duodenal and four fecal microbial species correlated almost exclusively with the translocation marker sCD14.

By contrast, the number of duodenal microbial species that correlated with translocation markers further increased to 12 in progressive ALD, 5 species correlating with sCD14 and 7 with PGRPs. Additionally, five species in the fecal samples showed a correlation principally with PGRPs. All individual correlations were statistically significant (p-values < 0.05). However, after adjusting for multiple comparisons, the q-values were greater than 0.5 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation between microbiota species in duodenum and stools and serum surrogate markers of microbial translocation sCD14 and PGRPs at different stages of alcoholic liver disease (ALD).

| Microbe | Gram | Marker | Coef | stderr | N | p-val | q-val |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-progressive ALD | |||||||

| Microbiota: duodenal | |||||||

| Gemella | Positive | PGRPs | −0.0014923 | 0.00044804 | 14 | 0.01037279 | 0.83197791 |

| Bacillus | Positive | sCD14 | −6.97E-06 | 2.53E-06 | 14 | 0.02498809 | 0.83197791 |

| Corynebacterium | Positive | sCD14 | −1.71E-05 | 6.28E-06 | 14 | 0.02598272 | 0.83197791 |

| Novosphingobium | Negative | sCD14 | −2.09E-06 | 6.95E-07 | 14 | 0.01674825 | 0.83197791 |

| Cloacibacterium | Negative | sCD14 | −2.76E-05 | 1.07E-05 | 14 | 0.03262759 | 0.83197791 |

| Sphingobacterium | Negative | sCD14 | −2.24E-06 | 8.89E-07 | 14 | 0.03591045 | 0.83197791 |

| Microbiota: fecal | |||||||

| Unclassified_Erysipelotrichaceae | Positive | sCD14 | −1.36E-05 | 5.86E-06 | 14 | 0.04246871 | 0.90377608 |

| Hespellia | Positive | sCD14 | 8.51E-06 | 3.70E-06 | 14 | 0.04430796 | 0.90377608 |

| Dialister | Negative | sCD14 | 5.85E-05 | 2.61E-05 | 14 | 0.04868563 | 0.90377608 |

| Clostridium_XlVb | Negative | sCD14 | 5.32E-06 | 2.38E-06 | 14 | 0.04903367 | 0.90377608 |

| Progressive ALD | |||||||

| Microbiota: duodenal | |||||||

| Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group | Negative | PGRPs | 6.06E-05 | 1.55E-05 | 9 | 0.011346 | 0.57354547 |

| Bergeyella | Negative | PGRPs | 0.00011534 | 3.19E-05 | 9 | 0.01527949 | 0.57354547 |

| Anaeroglobus | Negative | PGRPs | 0.00010158 | 3.09E-05 | 9 | 0.02190414 | 0.57354547 |

| Fretibacterium | Negative | PGRPs | 6.84E-05 | 2.13E-05 | 9 | 0.02375486 | 0.57354547 |

| Capnocytophaga | Negative | PGRPs | 0.00061948 | 0.00022807 | 9 | 0.04196674 | 0.57354547 |

| X.Eubacterium._nodatum_group | Positive | PGRPs | −5.78E-05 | 2.06E-05 | 9 | 0.03806405 | 0.57354547 |

| Abiotrophia | Positive | PGRPs | 0.00036362 | 0.0001331 | 9 | 0.04118104 | 0.57354547 |

| Bergeyella | Negative | sCD14 | 2.50E-06 | 7.41E-07 | 9 | 0.01968319 | 0.57354547 |

| Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group | Negative | sCD14 | 1.20E-06 | 3.60E-07 | 9 | 0.02062727 | 0.57354547 |

| Roseateles | Negative | sCD14 | −2.98E-06 | 9.85E-07 | 9 | 0.02921792 | 0.57354547 |

| Aeromonas | Negative | sCD14 | −2.65E-06 | 9.03E-07 | 9 | 0.03260309 | 0.57354547 |

| Enterococcus | Positive | sCD14 | 7.42E-06 | 2.59E-06 | 9 | 0.0351744 | 0.57354547 |

| Microbiota: fecal | |||||||

| Unclassified_Rikenellaceae | Negative | sCD14 | 1.60E-06 | 5.63E-07 | 11 | 0.02496945 | 0.89385681 |

| Gemella | Positive | PGRPs | 6.63E-05 | 2.65E-05 | 11 | 0.04072833 | 0.89385681 |

| Acidaminococcus | Negative | PGRPs | −0.000892 | 0.00035918 | 11 | 0.04200311 | 0.89385681 |

| Roseburia | Positive | PGRPs | −0.0050578 | 0.0020531 | 11 | 0.04324419 | 0.89385681 |

| Unclassified_Erysipelotrichaceae | Positive | PGRPs | 0.00154982 | 0.00065127 | 11 | 0.04890272 | 0.89385681 |

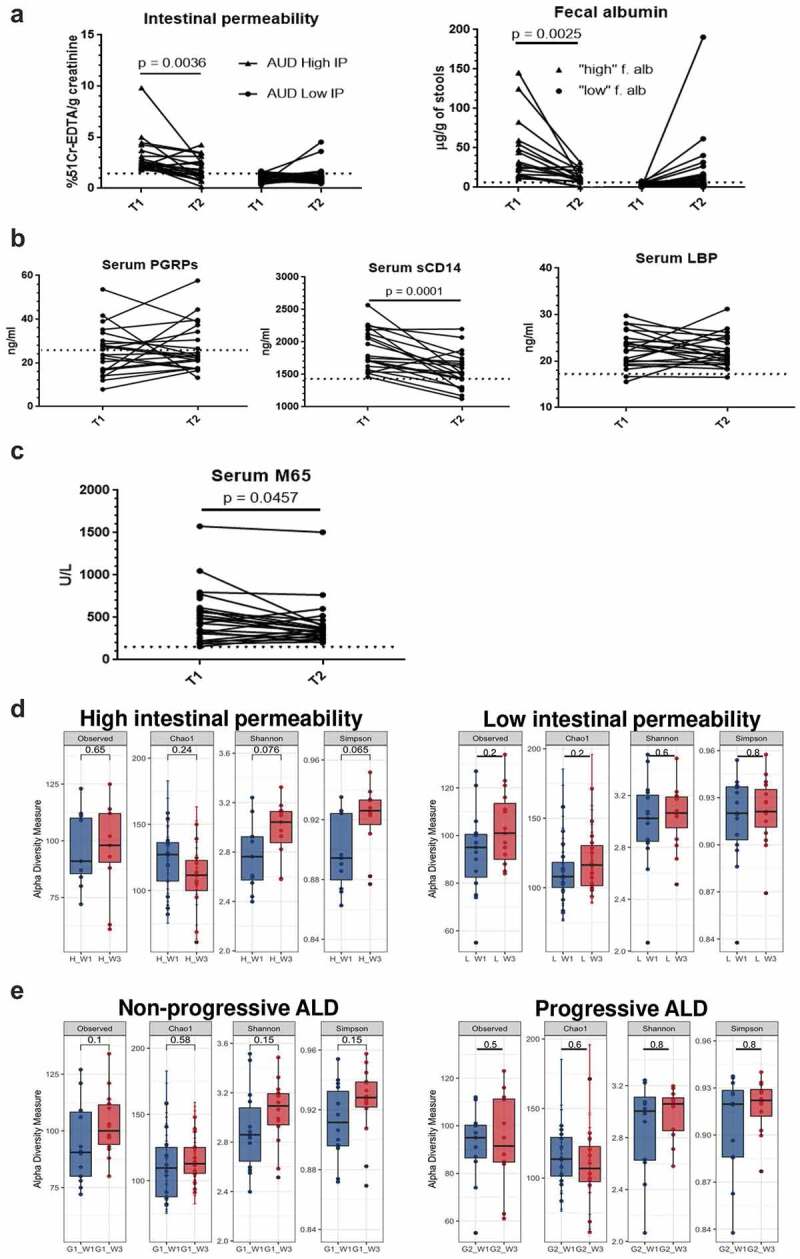

A short time of abstinence restores normal intestinal permeability and fecal microbiota but does not normalize microbial translocation and liver damage

In the absence of effective pharmacological therapy, abstinence constitutes the foundation of ALD treatment. We, therefore, assessed whether a short period of abstinence, often encountered in AUD patients, was able to restore alcohol-related changes in the gut and liver cell damage. We retested AUD patients who remained abstinent at the end of 3-wk detoxification program (T2). IP of AUD patients with both high 51Cr-EDTA urinary excretion and high fecal albumin content returned to values observed in the control group and remained low in those with already normal levels at admission (T1) (Figure 11a). In parallel, serum sCD14 levels also significantly decreased upon abstinence. By contrast, neither LBP nor PGRPs were modified by alcohol cessation (Figure 11b) suggesting the persistence of some microbial translocation. In addition, serum CK18-M65 decreased after abstinence (Figure 11c) but remained significantly higher than control levels, indicating persisting but attenuated liver damage.

Figure 11.

Impact of short time of abstinence on intestinal permeability (IP), microbial translocation, liver damage and microbiota composition.

(a) In AUD patients with both high 51Cr-EDTA urinary excretion and high fecal albumin content, levels returned to those observed in the control group (indicated with the dotted line) whereas no significant changes were found in AUD subjects with normal/low IP at T1. (b) Among microbial translocation markers, only serum soluble CD14 (sCD14) levels (middle) decreased upon abstinence but not LBP and PGRPs. (c) Levels of serum cytokeratin 18 (CK18-M65), a marker of liver cell damage, decreased significantly after abstinence but remained higher compared to controls (indicated with the dotted line). (d) Evenness (Shannon and Simpson) but not richness (observed species and Chao1) of the fecal microbiota increased in AUD patients with high intestinal permeability (left) after abstinence but not in those with initially normal intestinal permeability (right). (e) Observed species and evenness (Shannon and Simpson) were only slightly modified upon abstinence in AUD patients with non-progressive ALD but not in those with progressive ALD.

These observations indirectly confirm that increased IP is not absolutely required for microbial translocation to occur but sustain a potential association of bacterial translocation with liver disease.

The microbial composition in the stool was also assessed at the end of 3 week-detoxification in AUD patients subdivided according to both permeability and ALD stage. Interestingly, we found an increased evenness (Shannon and Simpson) only in AUD patients with high IP (Figure 11d) while the number of observed species remains the same. By contrast, α-diversity indexes did not change in AUD patients with normal intestinal permeability (Figure 11d). Regarding ALD stage, we found a minor change in α-diversity indexes (richness and evenness) only in AUD patients with non-progressive ALD but not in progressive ALD (Figure 11e). Overall, microbial profile (β-diversity) did not change upon abstinence (Supplementary Figures 10,11).

These results support and reinforce the concept of a possible link between fecal microbiota dysbiosis and leaky gut but not with ALD progression in humans.

Discussion

Our work addresses the link between the gut and the liver at early stages of ALD in a unique human cohort. We demonstrate for the first time that alterations in the duodenal mucosa-associated microbiota together with elevated translocation of either microbial products and/or microbes themselves are associated with liver disease progression in a large human cohort of AUD patients. Intriguingly, the increase of surrogate markers for Gram+, Gram-, and fungal microbial translocation in the blood of AUD patients compared to controls occurred independently from both paracellular and vascular IP, measured by 51Cr-EDTA and fecal albumin, respectively. Therefore, one might ask the question as to whether increased IP is absolutely required for microbes to cross the gut barrier. Microbial translocation might involve different mechanisms that do not necessarily depend on changes in paracellular and/or vascular gut leakiness. On the other hand, increased IP alone might also not be sufficient to cause microbial translocation unless additional mechanisms in the complex interactions between host and microbes in the gut fail.

Inappropriate immune responses and/or transcytosis in the gut, as shown in several situations26,40 but not investigated in our study, might be one of those mechanisms also implicated in ALD. We found a decreased number of immune cells, such as macrophages and T cells, in the duodenal mucosa of AUD patients as well as little, if any, upregulation of gut-specific pro-inflammatory cytokines. This argues against a major inflammatory component as a driver for morphological changes and microbial translocation. Rather, one might speculate that this unexpected but intriguing decrease in immune effector cells leads to reduced immunosurveillance that may allow microbes to cross the gut barrier and reach the blood circulation. Indeed, an appropriate immune defense in the intestine should ward off the translocation and control invasion of bacteria and fungi into the tissues.41

Goblet cells also contribute to mucosal immunosurveillance. They may form the so-called goblet cell-associated antigen passages (GAPs) to deliver microbial antigens to antigen-presenting cells within the lamina propria.40 It is tempting to speculate that under pathological conditions, microbes might also use this route in order to invade the intestine and finally enter the blood circulation. Thus, irrespectively of IP, the relative inefficiency of innate as well as adaptive components orchestrating the mucosal defense against microbial invaders, may explain, at least in part, our observation.

Gram-microbial translocation was associated with progressive ALD and correlated with liver cell damage marker CK18-M65. In addition, reduced richness with dominance shift toward potential pathogenic bacteria such as Streptococcus, Shuttleworthia, and Rothia characterized the duodenal-associated microbiota of AUD patients with progressive ALD. Intriguingly, all these genera belong to the Gram+ instead of Gram-bacteria. Thus, elevated sCD14 levels in the serum may not entirely reflect Gram-translocation because it recognizes ligands at the cell surface of both Gram- and Gram+ bacteria and it has been associated with Gram+ sepsis and mortality.42,43 Several studies reported a higher abundance in stool or saliva of Streptococcus in association with cirrhosis severity, decompensation, and encephalopathy.22,44-46 Interestingly, both Shuttleworthia and Rothia are part of the normal oral microflora47,48 and are overrepresented in the distal duodenum of AUD patients with progressive ALD compared to controls. These findings suggest a possible extension of the oral microflora further down into the duodenum as a potential determinant in ALD progression, as already speculated in advanced stages of liver disease.49 Proton pump inhibitor (PPIs) therapy50 cannot explain the overrepresentation of oral microflora components in the duodenum of AUD patients since only a minority (<20%; data not shown) took PPIs on admission. Notably, Rothia spp. are generally considered organisms of low virulence in immune-competent hosts but they have emerged as pathogens which can cause significant infections, for example, in patients with severe forms of liver disease.51 This predominance shift was accompanied by the diminution of important genera such as Mycobacterium, Alcaligenes, and Lachnoclostridium characterizing the mucosa of healthy volunteers. Interestingly, Alcaligenes spp. have been shown to be important for the development, maturation, and maintenance of an appropriate gut immune system52 and its loss could be deleterious for immune surveillance in the intestine of AUD patients. Thus, our results revealed that specific opportunistic pathogens become dominant in the patients’ small bowel mucosa who develop progressive ALD. Furthermore, the fact that intestinal permeability restores after short-term abstinence in opposite to microbial translocation (in particular Gram+) and liver damage indicates that both phenomena might indeed be linked. Our study confirms in humans, some observations made in mice of elevated translocation of microflora products related to disease severity.38,39

Neither intestinal inflammation, morphological changes in the duodenum nor enterocyte damage provided a convincing explanation for IP changes. The reduction in villi length found in AUD patients might be caused by alterations of the differentiation program in the small intestinal epithelium and could influence absorption of various important nutrients.53 Further studies are needed to investigate these processes and whether they result from toxicity related to alcohol and its metabolites and/or are caused by alterations of the intestinal microbiome/metabolome. We also reveal important conceptual differences between the duodenal mucosa-associated and the fecal microbiota in relation to IP and ALD progression. We found that only a subgroup of AUD patients is characterized by increased IP associated with dysbiosis of the fecal microbiota but not with changes in the microflora attached to the duodenal mucosa. The present results confirm our previous observation in a different cohort of AUD patients with no or mild liver disease where fecal microbiota changes were associated with high IP.24 Interestingly, metabolic analysis of fecal samples showed alterations of the metabolic profile linked to gut barrier dysfunction.24,54 51Cr-EDTA measurements suggest that the permeability of the colon is preserved in AUD patients with fecal dysbiosis (not shown) which raises the question of how those changes indirectly interfere with events that occur in the small bowel. One might speculate that specific microbial metabolites which could reach the circulation could be linked to increased IP and appropriate metabolomics analysis together with a mechanistic approach is needed in order to elucidate the mechanisms involved in this intriguing observation. By contrast, fecal dysbiosis was not associated with ALD progression. However, we cannot exclude a potential link given its association with increased IP which could act as a facilitator of microbial translocation.

An intrinsic limitation of this study is that data are mainly based on associations/correlations, which do not formally prove a cause-and-effect relationship. However, given the difficulties in accessing tissues at early-stage disease, we believe our study adds significant insights into the role of the gut-liver axis in the early pathogenesis of ALD. Certainly, the main strength of this investigation is the unique patient cohort of a high number of heavily, actively drinking AUD patients in whom distal duodenal biopsies with collections of the blood, stools, and urine have been performed in a strict, highly standardized clinical program. We used point of care noninvasive techniques (Fibroscan®, controlled attenuation parameter (CAP), AST, and ALT levels) to diagnose and stage liver disease in combination with serum CK18-M65 levels. This allowed the identification of liver damage with high accuracy even at early stages of ALD. A recent report underlines a benign disease course in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with normal transaminases.55 Other studies suggest an added value of CK-18, a component of the cytoskeleton of hepatocytes which is released in the blood upon cell damage56in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and viral disease.57–59 Our study extends current data on CK-18 also to ALD. The good diagnostic power of our integrated approach might prove useful for monitoring liver disease progression and/or regression in AUD patients.

Our observations may be relevant for clinical practice in the future since they suggest that many unfavorable factors are already linking the gut and the liver at early stages in human ALD. Short-term abstinence does not fully abolish microbial translocation, which can potentially lead to disease progression. Understanding the mechanisms underlying dysbiosis and translocation of microbes and/or their products into the blood circulation would provide us with new possible therapeutic targets at the frontlines of the complex host-microbes interactions during early human ALD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by NIH grants R01 AA24726 (to D.E.F., B.S., P.S.), U01 AA026939 (to D.E.F., B.S.) and services provided by P30 DK120515 and P50 AA011999, by grants from Fond National de Recherche Scientifique Belgium (J.0146.17 and T.0217.18) and Action de Recherche Concertée (ARC), Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium to P.S. We thank the IREC imaging platform for their support in analyzing the results.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Fonds national de la Recherche Scientifique - FNRS [J.0146.17]; Fonds national de la Recherche Scientifique - FNRS [T.0217.18]; National Institutes of Health [U01 AA026939]; National Institutes of Health [R01 AA24726]; Université Catholique de Louvain [ARC 2018].

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

B.S. has been consulting for Ferring Research Institute, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, HOST Therabiomics and Patara Pharmaceuticals. B.S.’s institution UC San Diego has received grant support from BiomX, NGM Biopharmaceuticals, CymaBay Therapeutics, and Synlogic Operating Company. P.S. received grant support from Gilead Sciences Belgium.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- 1.Hammer JH, Parent MC, Spiker DA. World Health Organization . Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Vol. 65; 2018. doi: 10.1037/cou0000248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stärkel P, Leclercq S, de Timary P, Schnabl B.. Intestinal dysbiosis and permeability: the yin and yang in alcohol dependence and alcoholic liver disease. Clin Sci. 2018;132(2):199–23. doi: 10.1042/CS20171055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bull-Otterson L, Feng W, Kirpich I, Wang Y, Qin X, Liu Y, Gobejishvili L, Joshi-Barve S, Ayvaz T, Petrosino J, et al. Metagenomic analyses of alcohol induced pathogenic alterations in the intestinal microbiome and the effect of lactobacillus rhamnosus GG treatment. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):4–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan AW, Fouts DE, Brandl J, Stärkel P, Torralba M, Schott E, Tsukamoto H, Nelson EK, Brenner AD, Schnabl B, et al. Enteric dysbiosis associated with a mouse model of alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53(1):96–105. doi: 10.1002/hep.24018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worthington BS, Meserole L, Syrotuck JA. Effect of daily ethanol ingestion on intestinal permeability to macromolecules. Am J Dig Dis. 1978;23(1):23–32. doi: 10.1007/BF01072571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draper LR, Gyure LA, Hall JG, Robertson D. Effect of alcohol on the integrity of the intestinal epithelium. Gut. 1983;24(5):399–404. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.5.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartmann P, Seebauer CT, Schnabl B. Alcoholic liver disease: the gut microbiome and liver cross talk. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(5):763–775. doi: 10.1111/acer.12704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen P, Stärkel P, Turner JR, Ho SB, Schnabl B. Dysbiosis-induced intestinal inflammation activates tumor necrosis factor receptor I and mediates alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology. 2015;61(3):883–894. doi: 10.1002/hep.27489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang L, Fouts DE, Stärkel P, Hartmann P, Chen P, Llorente C, DePew J, Moncera K, Ho S, Brenner D, et al. Intestinal REG3 lectins protect against alcoholic steatohepatitis by reducing mucosa-associated microbiota and preventing bacterial translocation. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(2):227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendrikx T, Duan Y, Wang Y, Oh J-H, Alexander LM, Huang W, Stärkel P, Ho SB, Gao B, Fiehn O, et al. Bacteria engineered to produce IL-22 in intestine induce expression of REG3G to reduce ethanol-induced liver disease in mice. Gut. 2019;68(8):1504–1515. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen P, Torralba M, Tan J, Embree M, Zengler K, Stärkel P, van Pijkeren J-P, DePew J, Loomba R, Ho SB, et al. Supplementation of saturated long-chain fatty acids maintains intestinal eubiosis and reduces ethanol-induced liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(1):203–214.e16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartmann P, Chen P, Wang HJ, Wang L, McCole DF, Brandl K, Stärkel P, Belzer C, Hellerbrand C, Tsukamoto H, et al. Deficiency of intestinal mucin-2 ameliorates experimental alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology. 2013;58(1):108–119. doi: 10.1002/hep.26321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkin RJW, Lalor PF, Parker R, Newsome PN. Murine models of acute alcoholic hepatitis and their relevance to human disease. Am J Pathol. 2016;186(4):748–760. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabakoff B, Hoffman PL. Animal models in alcohol research. Alcohol Res Heal. 2000;24:77–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cederbaum IA. Metabolism alcohol. Clin Liver Dis. 2013;16(4):667–685. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002.ALCOHOL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mestas J, Hughes CCW. Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology. J Immunol. 2004;172(5):2731–2738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen TLA, Vieira-Silva S, Liston A, Raes J. How informative is the mouse for human gut microbiota research? DMM Dis Model Mech. 2015;8(1):1–16. doi: 10.1242/dmm.017400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao B, Xu MJ, Bertola A, Wang H, Zhou Z, Liangpunsakul S. Animal models of alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and clinical relevance. Gene Expr. 2017;17(3):173–186. doi: 10.3727/105221617X695519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mutlu EA, Gillevet PM, Rangwala H, Sikaroodi M, Naqvi A, Engen PA, Kwasny M, Lau CK, Keshavarzian A. Colonic microbiome is altered in alcoholism. Am J Physiol - Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302(9). doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00380.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kisseleva T, Keshavarzian A, Wang L, Chen C-S, Moncera K, Mutlu EA, Yang A-M, Inamine T, Mehal WZ, Schnabl B, et al. Intestinal fungi contribute to development of alcoholic liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(7):2829–2841. doi: 10.1172/jci90562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Llopis M, Cassard AM, Wrzosek L, Boschat L, Bruneau A, Ferrere G, Puchois V, Martin JC, Lepage P, Le Roy T, et al. Intestinal microbiota contributes to individual susceptibility to alcoholic liver disease. Gut. 2016;65(5):830–839. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Yang F, Lu H, Wang B, Chen Y, Lei D, Wang Y, Zhu B, Li L. Characterization of fecal microbial communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;54(2):562–572. doi: 10.1002/hep.24423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Addolorato G , Ponziani FR, Dionisi T , Mosoni C , Vassallo GA , Sestito L , Petito V , Picca A, Marzetti E , Tarli C, et al. Gut microbiota compositional and functional fingerprint in patients with alcohol use disorder and alcohol associated liver disease. Liver Int 2020 Apr;40(4):878-888. doi: 10.1111/liv.14383.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leclercq S, Matamoros S, Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Jamar F, Stärkel P, Windey K, Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F, Verbeke K, et al. Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(42):E4485–E4493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415174111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leclercq S, Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Stärkel P, Jamar F, Mikolajczak M, Delzenne NM, de Timary P. Role of intestinal permeability and inflammation in the biological and behavioral control of alcohol-dependent subjects. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(6):911–918. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dillon A, Lo DD. M cells: intelligent engineering of mucosal immune surveillance. Front Immunol. 2019;10(JUL):1–13. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Llorente C, Jepsen P, Inamine T, Wang L, Bluemel S, Wang HJ, Loomba R, Bajaj JS, Schubert ML, Sikaroodi M, et al. Gastric acid suppression promotes alcoholic liver disease by inducing overgrowth of intestinal enterococcus. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1). doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00796-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duan Y, Llorente C, Lang S, Brandl K, Chu H, Jiang L, White RC, Clarke TH, Nguyen K, Torralba M, et al. Bacteriophage targeting of gut bacterium attenuates alcoholic liver disease. Nature. 2019;575(7783):505–511. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1742-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One. 2013;8(4). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12(6):R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stärkel P, De Saeger C, Strain AJ, Leclercq I, Horsmans Y. NFκB, cytokines, TLR 3 and 7 expression in human end-stage HCV and alcoholic liver disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40(7):575–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mueller S, Nahon P, Rausch V, Peccerella T, Silva I, Yagmur E, Straub BK, Lackner C, Seitz HK, Rufat P, et al. Caspase-cleaved keratin-18 fragments increase during alcohol withdrawal and predict liver-related death in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2017;66(1):96–107. doi: 10.1002/hep.29099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang L, Llorente C, Hartmann P, Yang AM, Chen P, Schnabl B. Methods to determine intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation during liver disease. J Immunol Methods. 2015;421:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spadoni I, Zagato E, Bertocchi A, Paolinelli R, Hot E, Di Sabatino A, Caprioli F, Bottiglieri L, Oldani A, Viale G, et al. A gut-vascular barrier controls the systemic dissemination of bacteria. Science 2015;350(6262):830–834. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stehle JR, Leng X, Kitzman DW, Nicklas BJ, Kritchevsky SB, High KP. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, a surrogate marker of microbial translocation, is associated with physical function in healthy older adults. Journals Gerontol - Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(11):1212–1218. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Bornstein E, Lambotte O, Altmann D, et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12(12):1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Royet J, Gupta D, Dziarski R. Peptidoglycan recognition proteins: modulators of the microbiome and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(12):837–851. doi: 10.1038/nri3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adachi Y, Moore LE, Bradford BU, Gao W, Thurman RG. Antibiotics prevent liver injury in rats following long-term exposure to ethanol. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(1):218–224. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Enomoto N, Yamashina S, Kono H, Schemmer P, Rivera CA, Enomoto A, Nishiura T, Nishimura T, Brenner DA, Thurman RG, et al. Development of a new, simple rat model of early alcohol-induced liver injury based on sensitization of Kupffer cells. Hepatology. 1999;29(6):1680–1689. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knoop KA, McDonald KG, McCrate S, McDole JR, Newberry RD. Microbial sensing by goblet cells controls immune surveillance of luminal antigens in the colon. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8(1):198–210. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmad R, Sorrell MF, Batra SK, Dhawan P, Singh AB. Gut permeability and mucosal inflammation: bad, good or context dependent. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10(2):307–317. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korpelainen S, Intke C, Hämäläinen S, Jantunen E, Juutilainen A, Pulkki K. Soluble CD14 as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in hematological patients with febrile neutropenia. Dis Markers. 2017;2017:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2017/9805609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burgmann H, Winkler S, Locker GJ, Presterl E, Laczika K, Staudinger T, Knapp S, Thalhammer F, Wenisch C, Zedwitz-Liebenstein K, et al. Increased serum concentration of soluble CD14 is a prognostic marker in gram-positive sepsis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;80(3II):307–310. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y, Guo J, Qian G, Fang D, Shi D, Guo L, Li L. Gut dysbiosis in acute-on-chronic liver failure and its predictive value for mortality. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(9):1429–1437. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qin N, Yang F, Li A, Prifti E, Chen Y, Shao L, Guo J, Le Chatelier E, Yao J, Wu L, et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature. 2014;513(7516):59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature13568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bajaj JS, Betrapally NS, Hylemon PB, Heuman DM, Daita K, White MB, Unser A, Thacker LR, Sanyal AJ, Kang DJ, et al. Salivary microbiota reflects changes in gut microbiota in cirrhosis with hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2015;62(4):1260–1271. doi: 10.1002/hep.27819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Downes J, Munson MA, Radford DR, Spratt DA, Wade WG. Shuttleworthia Satelles Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., Isolated from the human oral cavity. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;Sep;52(Pt 5):1469–1475. doi:10.1099/00207713-52-5-1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zamakhchari M, Wei G, Dewhirst F, Lee J, Schuppan D, Oppenheim FG, Helmerhorst EJ. Identification of rothia bacteria as gluten-degrading natural colonizers of the upper gastro-intestinal tract. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Acharya C, Sahingur SE, Bajaj JS. Microbiota, cirrhosis, and the emerging oral-gut-liver axis. JCI Insight. 2017 Oct 5;2(19):e94416. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.94416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jackson MA, Goodrich JK, Maxan M-E, Freedberg DE, Abrams JA, Poole AC, Sutter JL, Welter D, Ley RE, Bell JT, et al. Proton pump inhibitors alter the composition of the gut microbiota. Gut. 2016;65(5):749–756. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abidi MZ, Ledeboer N, Banerjee A, Hari P.. Morbidity and mortality attributable to rothia bacteremia in neutropenic and nonneutropenic patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;85(1):116–120. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kunisawa J, Kiyono H. Alcaligenes is commensal bacteria habituating in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue for the regulation of intestinal IgA responses. Front Immunol. 2012;3(APR):2009–2013. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moor AE, Harnik Y, Ben-moshe S, Massasa EE, Rozenberg M, Eilam R, Halpern KB, Itzkovitz S. Spatial reconstruction of single enterocytes uncovers broad zonation along the intestinal villus axis spatial reconstruction of single enterocytes uncovers broad zonation along the intestinal villus axis. Cell. 2018;1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao B, Lang S, Duan Y, Wang Y, Shawcross DL, Louvet A, Mathurin P, Ho SB, Stärkel P, Schnabl B, et al. Serum and fecal oxylipins in patients with alcohol-related liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(7):1878–1892. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05638-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Natarajan Y, Kramer JR, Yu X, Li L, Thrift AP, El‐Serag HB, Kanwal F. Risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer in patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease and normal liver enzymes. Hepatology. 2020;0–3. doi: 10.1002/hep.31157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ku NO, Strnad P, Bantel H, Omary MB. Keratins: biomarkers and modulators of apoptotic and necrotic cell death in the liver. Hepatology. 2016;64(3):966–976. doi: 10.1002/hep.28493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong VWS, Adams LA, de Lédinghen V, Wong GLH, Sookoian S. Noninvasive biomarkers in NAFLD and NASH — current progress and future promise. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(8):461–478. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Darweesh SK, Abdelaziz RA, Abd-Elfatah DS, AbdElazim NA, Fathi SA, Attia D, AbdAllah M. Serum cytokeratin-18 and its relation to liver fibrosis and steatosis diagnosed by FibroScan and controlled attenuation parameter in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis C virus patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31(5):633–641. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.He L, Deng L, Zhang Q, Guo J, Zhou J, Song W, Yuan F. Diagnostic value of CK-18, FGF-21, and related biomarker panel in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2017/9729107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.