Abstract

Background

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a form of behavioral therapy that teaches people to learn to accept rather than avoid challenging situations in their lives. ACT has shown to be an intervention with great success in the reduction of various mental disorders and substance use disorders (SUDs). The core of ACT when used in SUD treatment is guiding people to accept the urges and symptoms associated with substance misuse (acceptance) and use psychological flexibility and value-based interventions to reduce those urges and the symptoms (commitment). The purpose of this study is to review the existing literature to examine the evidence on the use of ACT in the management of SUD.

Methods

A thorough search of four databases (CINAHL, PubMed.gov, PsycINFO and PsycNET) from 2011 to 2020 was conducted using search terms like ACT, ACT and SUD, ACT, and substance misuse. The articles retrieved were critically appraised using the Critically Appraised Topic (CAT) Checklist.

Results

Most of the studies showed that ACT was effective in the management of SUD showing significant evidence of a reduction in substance use or total discontinuation with subsequent abstinence.

Conclusions

The literature review concluded that success has been achieved using ACT either as monotherapy or in combination with other therapy in the treatment of individuals with SUD.

Keywords: Acceptance and commitment therapy, Substance use disorders, Cognitive behavioral therapy, Reduction, Psychological flexibility

Introduction

Substance use disorder (SUD) is a global pandemic. Worldwide, about 172 to 250 million people aged from 15 to 65 years have used an illicit substance at least once in their lifetime [1]. The burden of this problem is high in the USA with 20.3 million people having SUDs [2]. SUD occurs when an individual continues to seek and use substances despite the problems and impairment that occurs from the use of the substance [3]. The substances included in the list for SUD include alcohol, cannabis, hallucinogens, phencyclidine, opioids, sedatives, stimulants, tobacco, and others [4]. To make a diagnosis of SUD, the person must have two or more out of the 11 symptoms described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) which can be classified as mild, four or more symptoms for moderate, and six or more symptoms for the severe form [4]. The symptoms include substances ingested in greater amounts and/or for a longer duration of time, concerted efforts, or aggressive actions to regulate or minimize substance use, and a vast amount of time is expended on activities to acquire, use, or recover from the substance’s effects [4]. There is a compulsion, inclination, or intense desire to use the drug, repeated use of substances, failure to meet certain designated responsibilities at work, school or home, and the ongoing use of drugs amid chronic social or behavioral issues induced or worsened by the use of substances. There is recurring use of a drug in potentially dangerous conditions. There is the continued use of drugs, even with the awareness that the drug is likely to have induced or worsened a chronic physical or psychological condition. Tolerance or withdrawal is another criterion [4]. There is recurrent substance use in situations that is physically hazardous.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is an intervention developed from the relational frame theory (RCT). It is a form of third-wave behavioral therapy. This form of therapy uses six processes of adaptation. They include defusion, acceptance, flexible attention to the present moment, self-as-a-context, values and committed actions [5]. ACT’s greatest focus is on psychological flexibility which is described by Hayes et al as the capability of a human being to confront the present moment and alter his actions to achieve the desired effect [5]. The core of ACT when used in SUD is for people to accept the urge and symptoms associated with substance misuse (acceptance) and then use psychological flexibility and value-based interventions to reduce the urge and symptoms (commitment) [5]. ACT is different from other behavioral therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). In CBT, people try to avoid or replace the urge and symptoms associated with substance use with more positive things rather than confronting and accepting that they exist and looking for ways to improve or overcome the challenges [6]. ACT has shown to be a very successful intervention in the reduction of various mental disorders [7-9]. Studies also show its effectiveness as a monotherapy or in combination with other therapies for the treatment of people with SUD [8, 10-13]. The effectiveness of ACT therapy has been shown and documented in different populations, such as adolescents, veterans, inmates, and geriatrics [14-16]. ACT is successful in many clinical settings (inpatient, outpatient, and drug treatment clinics) [8, 12, 17-19]. This paper aims to review the existing literature on the use of ACT alone or in combination with other therapies in the treatment of SUDs (Table 1) [20].

Table 1. Benefits/Challenges of ACT.

| Number | Benefits of ACT | Challenges with the use of ACT |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acceptance allows individuals who are experiencing problems to think about those problems without developing anxiety or feeling guilty [20]. | ACT requires a lot of sessions to achieve a therapeutic effect [20]. |

| 2 | Cognitive diffusion in ACT enables individuals to experience negative thoughts and emotions to challenge their behavior without fixating on them [20]. | Limited availability of specialized and certified people to coach people on ACT [20]. |

| 3 | Mindfulness in ACT helps people to be aware of their negative feeling without been judgmental towards themselves or trying to change the situation [20]. | |

| 4 | The commitment aspect of ACT helps the individual to achieve their long-term goals by focusing on the values that will help them get better [20]. | |

| 5 | ACT helps individuals to become psychologically more flexible [20]. |

ACT: acceptance and commitment therapy.

Methods

To review existing literature on this topic, the authors highlighted both inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were: 1) Studies that looked at the impact of the utilization of ACT alone or in combination with different therapies for the treatment of SUDs; 2) Studies that looked at the population with single or multiple SUDs; 3) Studies that measure a reduction in SUD, abstinence from substance abuse, and/or complete discontinuation of misused substance as a primary outcome; and 4) Studies published on the use of ACT for SUDs between the time frame of 2011 and 2020. The exclusion criteria were: 1) Studies greater than 10 years; 2) Non-English language articles; 3) Studies that do not measure a reduction in SUD, abstinence from substance abuse, and/or complete discontinuation of misused substance as a primary outcome; and 4) Studies that do not use ACT as a primary intervention.

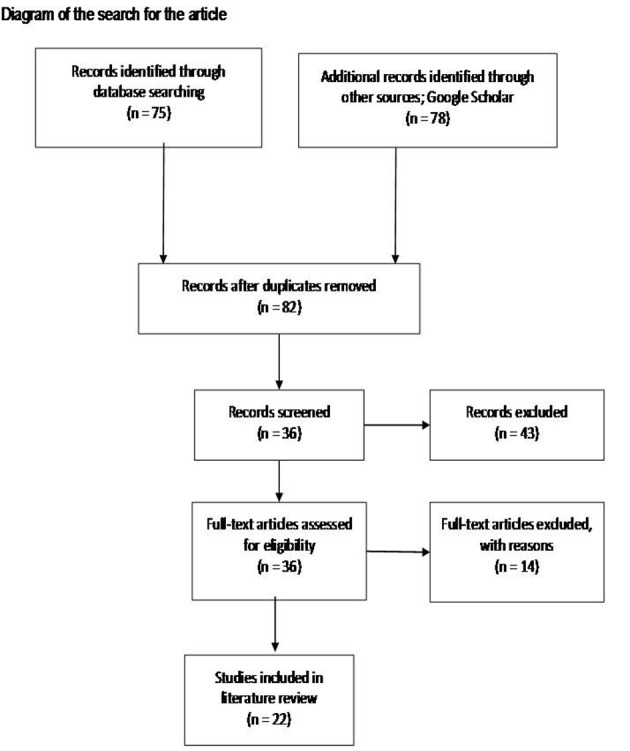

Using these criteria, the authors searched four databases: CINAHL, PubMed.gov, PsycINFO, and PsycNET. We used search terms: ACT, ACT and SUD, ACT, and substance misuse. Initial search generated 1,242 articles, which were modified to include the articles from 2011 to 2020. The search yielded 82 articles after applying exclusion criteria, and later duplicate articles were removed. A total of 36 publications made the eligibility list after further screening. Of these publications, using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 22 relevant articles were included in the review, while 14 were excluded in final round by the authors because they did not measure reduction or abstinence of their primary outcome. Figure 1 highlights the flow of this search.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the search for the articles.

To critically appraise the articles extracted, we used certain elements from the Critically Appraised Topic (CAT) Checklist and Guide Questions Sullivan 2008 [21]. We also use the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice; Evidence Level and Quality Guide [22]. Supplementary Material 1 (www.jocmr.org) shows the critical appraisal of the articles retrieved.

Discussion

To discuss the results and relevance of ACT in SUD, the authors grouped the articles under subheadings to reflect the nature of SUD, interventions, participants, and environment where ACT was used.

Remote/electronic-based ACT for SUDs

In 2015, Jones et al conducted a randomized control trial (RCT) on the web-based ACT and smoking cessation treatment for smokers with depressive symptoms. There was a randomization of 98 individuals who met the inclusion criteria; they were grouped into Webquit.org (ACT) or Smokefree.gov. The results revealed a higher quit rate (20% to 12%) in the Webquit.org participants than the Smokefree.gov [23]. A similar study conducted by Bricker et al in 2013 showed that the participants who used Webquit.org had a higher quit rate (23% to 10%) compared to those who used Smokefree.gov [11]. Bricker et al [12] demonstrated a similar result using the telephone app Smartquit (ACT) versus the Quitguide (the National Cancer Institute’s Quiet Guide App) for smoking cessation. This study randomized 196 participants and results showed that 13% of the Smartquit participants quit smoking after 3 months of follow-up compared with 8% of the Quitguide participants. The Smartquit participants at 2 months also showed an increase in the acceptance of cravings of tobacco (P < 0.04) [6].

In all these studies, the sample sizes were small, making it difficult to apply the findings to the general population. The studies using the web-based approach were not blinded and could result in reporting bias. The study from Jones et al did not show a statistically significant quit rate amongst the groups (P = 0.42) [23]. There was a high attrition rate, with only 45 of the 98 participants completing the study. The results from the study were also dependent upon self-reporting of abstinence and the use of the apps [24]. This may introduce bias that could affect the internal validity of the studies.

ACT for incarcerated/institutionalized/residential patients with SUDs

Studies using ACT alone or combined with other methods for treatment of SUD have been experimented on incarcerated, institutionalized, or residential patients [16, 24, 25]. In a RCT on 31 incarcerated women with SUDs, the participants in the control group were on a waiting list [24]. There was a 27.8% increase in abstinence from the use of drugs at the end of the treatment period which increased to 43.8% at a 6-month follow-up [26]. When ACT was compared with CBT in 50 women residing in the state prison in Spain, ACT showed significant improvement in reducing drug use (43.8% in ACT vs. 26.7% in CBT) after 6 months [16]. Another study conducted on patients in a residential substance treatment found that there was no statistically significant difference between the ACT and mindfulness group and the treatment as usual (TAU) after 28 - 30 days of treatment in a drug treatment residential facility. TAU consisted of programs like Alcohol Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous. There was no follow-up of the patients [25]. These studies used a small sample size making generalizability difficult. The low sample sizes may also increase the likelihood of a type II error. The studies did not blind the researchers or participants, which can affect the internal validity arising from the Hawthorne effect or reporter’s bias [27].

The use of ACT in the treatment of single substance abuse

ACT is an intervention that has shown a lot of promises in patients with single SUD. Two studies have shown ACT as an effective therapy for alcohol use disorder. Meyer et al in 2018 carried out an uncontrolled pilot study of 43 veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [28]. At the end of 10 to 12 sessions of ACT with TAU, the veterans demonstrated a significant reduction in the total number of drinks and heavy drinking days [28]. Ehman and Gross in 2018 also conducted a case study on a 29-year-old woman who was a college student and had AUD. She showed a lot of commitment to ACT therapy. At the end of the treatment period, she reported a significant reduction in the number of consumption episodes and severe drinking [29]. The study by Meyer et al was prone to type 1 error because of its limited sample size. The lack of controls would introduce bias from confounding variables [28]. The results obtained were from self-reporting which may lead to reporting bias. Finally, the study had a high attrition rate of 33%. This high attrition rate would affect the external validity of this article [28]. The study by Ehman and Gross is a case study whose outcome cannot be generalized to the entire population [29]. Several studies showed the influence of ACT on smoking cessation. These studies utilized in-person interventions, web-based solutions, or mobile apps to deliver therapy to participants [11, 12, 23, 30]. The outcomes were a significant reduction in smoking, decreased cravings, and increased psychological flexibility [12, 23, 28]. The studies had limitations like small sample size, lack of blinding, and very high attrition rates. These limitations would introduce significant biases in the results obtained in the studies [3]. A preliminary study on 30 men who misused methamphetamine attending a drug rehabilitation center in Tehran showed a significant reduction in addiction to methamphetamine [8]. This study did not compare ACT with any other form of therapy. The sample size in the study was small, and the participants were all men. These limitations would make it difficult to apply this study to the general population. It would also increase the chance of a type I error [27]. A study conducted on the use of ACT in the treatment of methadone by Stotts et al did not show any statistically significant difference when compared to regular drug counseling [17].

The use of ACT in the treatment of multiple SUD

Two groups of researchers (Luoma et al and Lanza et al) performed two different researches on the use of ACT in the management of SUDs. The studies found a significant reduction in substance use after 4 months and 6 months [10, 16]. ACT was used in the management of female inmates on a long-term basis, with a significant reduction in substance misuse after 18 months [13]. A study conducted on 111 patients in a residential home did not find any statistically significant difference between ACT and TAU [25]. There was no long-term follow-up of the patients. This lack of follow-up may have affected the outcome of the treatment [25]. In all the studies mentioned above, the sample sizes were small, and the researchers and participants were not blinded. These limitations can affect both the internal and external validity of these studies [27].

Limitations

The most common limitations highlighted by the authors of the articles reviewed were the small sample sizes, lack of blinding, and self-reporting of abstinence and reduction in the use of the substance. Further relevant studies may be present in databases other than the ones used for this review. However, the databases which the authors selected are the standard databases for archiving literature in this field. Our selected search terms may have also missed relevant studies. As discussed, there is a risk of bias with regards to generalizing some of the results due to small sample size and short-term follow-up. There should be studies in future to show the efficacy of ACT on SUD in the different genders and age groups.

Further direction

Looking at the gaps in the existing literature of small sample size which may lead to bias of lack of generalizability of the studies on the ACT program, a recommendation for large scale multicenter studies on the use of ACT for SUD in different populations and settings is needed and desired.

Conclusions

In conclusion, ACT has shown to be a promising therapy to be used in the management of patients with SUD. Most of the articles reviewed in this study showed significant reductions in the use of the substance immediately post-treatment and on the follow-up of the participants.

Supplementary Material

The Critical Appraisal of the Articles Retrieved.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

JO and CO contributed to the design of the study, data collection, interpretation of the data, helped to write the final draft of the manuscript, and have full access to all the data in the study as the primary authors of the manuscript. SA contributed to the design of the study and supervised the writing of the final draft of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. World Health Organization, W.H.O. Atlas on substance use (2010): resources for the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders. World Health Organization. 2009. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500616.

- 2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2019. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

- 3.Medina J. Psychosocial Treatments for Alcohol Use Disorder. Psych Central. 2020. https://psychcentral.com/addictions/alcohol-use-disorder-psychosocial-treatments/

- 4.Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM 5 Spl edition (Pb 2017) (5th ed) Cbs Publishing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayes SC, Pistorello J, Levin ME. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a unified model of behavior change. The Counseling Psychologist. 2012;40(7):976–1002. doi: 10.1177/0011000012460836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bricker JB, Bush T, Zbikowski SM, Mercer LD, Heffner JL. Randomized trial of telephone-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy versus cognitive behavioral therapy for smoking cessation: a pilot study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(11):1446–1454. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berglund E, Anderzen I, Andersen A, Carlsson L, Gustavsson C, Wallman T, Lytsy P. Multidisciplinary intervention and acceptance and commitment therapy for return-to-work and increased employability among patients with mental illness and/or chronic pain: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2424. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahrami S, Asghari F. A controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy for addiction severity in methamphetamine users: preliminary study. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2017;19(2):49–55. doi: 10.12740/APP/68159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Donoghue E, Clark A, Richardson M, Hodsoll J, Nandha S, Morris E, Kane F. et al. Balancing ACT: evaluating the effectiveness of psychoeducation and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) groups for people with bipolar disorder: study protocol for pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):436. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2789-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luoma JB, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Fletcher L. Slow and steady wins the race: a randomized clinical trial of acceptance and commitment therapy targeting shame in substance use disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(1):43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0026070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bricker J, Wyszynski C, Comstock B, Heffner JL. Pilot randomized controlled trial of web-based acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(10):1756–1764. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bricker JB, Mull KE, Kientz JA, Vilardaga R, Mercer LD, Akioka KJ, Heffner JL. Randomized, controlled pilot trial of a smartphone app for smoking cessation using acceptance and commitment therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;143:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Menendez A, Fernandez P, Rodriguez F, Villagra P. Long-term outcomes of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in drug-dependent female inmates: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2014;14(1):18–27. doi: 10.1016/S1697-2600(14)70033-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dindo L, Zimmerman MB, Hadlandsmyth K, StMarie B, Embree J, Marchman J, Tripp-Reimer T. et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for prevention of chronic postsurgical pain and opioid use in at-risk veterans: a pilot randomized controlled study. J Pain. 2018;19(10):1211–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eilenberg T, Fink P, Jensen JS, Rief W, Frostholm L. Acceptance and commitment group therapy (ACT-G) for health anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2016;46(1):103–115. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanza PV, Garcia PF, Lamelas FR, Gonzalez-Menendez A. Acceptance and commitment therapy versus cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of substance use disorder with incarcerated women. J Clin Psychol. 2014;70(7):644–657. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stotts AL, Green C, Masuda A, Grabowski J, Wilson K, Northrup TF, Moeller FG. et al. A stage I pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy for methadone detoxification. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(3):215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thurstone C, Hull M, Timmerman J, Emrick C. Development of a motivational interviewing/acceptance and commitment therapy model for adolescent substance use treatment. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2017;6(4):375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghouchani S, Molavi N, Massah O, Sadeghi M, Mousavi SH, Noroozi M, Sabri A. et al. Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) on aggression of patients with psychosis due to methamphetamine use: A pilot study. Journal of Substance Use. 2018;23(4):402–407. doi: 10.1080/14659891.2018.1436602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feliu-Soler A, Montesinos F, Gutierrez-Martinez O, Scott W, McCracken LM, Luciano JV. Current status of acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a narrative review. J Pain Res. 2018;11:2145–2159. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S144631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sullivan. Critically Appraised Topic (CAT) Checklist and Guide Questions. Critically Appraised Topic (CAT) Checklist and Guide Questions, 1-12. 2008. https://www.nuhs.edu/media/25485/studyguide-criticalappraisalforresearchpapers.pdf.

- 22.Hunt J. Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice. Nursing Management. 2012;19(7):8. doi: 10.7748/nm.19.7.8.s3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones HA, Heffner JL, Mercer L, Wyszynski CM, Vilardaga R, Bricker JB. Web-based acceptance and commitment therapy smoking cessation treatment for smokers with depressive symptoms. J Dual Diagn. 2015;11(1):56–62. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2014.992588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villagra Lanza P, Gonzalez Menendez A. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for drug abuse in incarcerated women. Psicothema. 2013;25(3):307–312. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2012.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shorey RC, Elmquist J, Gawrysiak MJ, Strauss C, Haynes E, Anderson S, Stuart GL. A randomized controlled trial of a mindfulness and acceptance group therapy for residential substance use patients. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52(11):1400–1410. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1284232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davoudi M, Omidi A, Sehat M, Sepehrmanesh Z. The effects of acceptance and commitment therapy on man smokers' comorbid depression and anxiety symptoms and smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Addict Health. 2017;9(3):129–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houser J. Nursing Research: Reading, Using and Creating Evidence (4th ed.) Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer EC, Walser R, Hermann B, La Bash H, DeBeer BB, Morissette SB, Kimbrel NA. et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol use disorders in veterans: pilot treatment outcomes. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(5):781–789. doi: 10.1002/jts.22322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ehman AC, Gross AM. Acceptance and commitment therapy and motivational interviewing in the treatment of alcohol use disorder in a college woman: a case study. Sage Journal. 2018;18(1):36–53. doi: 10.1177/1534650118804886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Connor M, Whelan R, Bricker J, McHugh L. Randomized controlled trial of a smartphone application as an adjunct to acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation. Behav Ther. 2020;51(1):162–177. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The Critical Appraisal of the Articles Retrieved.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.