Abstract

Objectives

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused many nursing homes to prohibit resident visits to prevent viral spread. Although visiting restrictions are instituted to prolong the life of nursing home residents, they may detrimentally affect their quality of life. The aim of this study was to capture perspectives from the relatives of nursing home residents on nursing home visiting restrictions.

Design

A cross-sectional online survey was conducted.

Setting and Participants

A convenience sample of Dutch relatives of nursing home residents (n = 1997) completed an online survey on their perspectives regarding nursing home visiting restrictions.

Methods

The survey included Likert-item, multiselect, and open-answer questions targeting 4 key areas: (1) communication access to residents, (2) adverse effects of visiting restrictions on residents and relatives, (3) potential protective effect of visiting restrictions, (4) important aspects for relatives during and after visiting restrictions.

Results

Satisfaction of communication access to nursing home residents was highest when respondents had the possibility to communicate with nursing home residents by nurses informing them via telephone, contact behind glass, and contact outside maintaining physical distance. Satisfaction rates increased when respondents had multiple opportunities to stay in contact with residents. Respondents were concerned that residents had increased loneliness (76%), sadness (66%), and decreased quality of life (62%), whereas study respondents reported personal sadness (73%) and fear (26%). There was no consensus among respondents if adverse effects of the visiting restrictions outweighed the protective effect for nursing home residents. Respondents expressed the need for increased information, communication options, and better safety protocols.

Conclusion and Implications

Providing multiple opportunities to stay in touch with nursing home residents can increase satisfaction of communication between residents and relatives. Increased context-specific information, communication options, and safety protocols should be addressed in national health policy.

Keywords: COVID-19, visiting restrictions, relatives, perspectives, policy, nursing home

Institutionalized older adults have the highest risk of mortality from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).1, 2, 3 Many governments, including the Netherlands, instituted visiting restrictions in nursing homes to control contagion and avoid high mortality numbers.4 For many nursing home residents, this caused isolation from their family and friends.5

Isolating policies are widely recommended to prevent COVID-19 contagion6 , 7; however, consequential detrimental effects of isolating nursing home residents on quality of life are known from the 2003 SARS outbreak.8 A qualitative study of McCleary8 found that as a result of nursing home visiting restrictions during the 2003 SARS outbreak, both nursing home residents and their relatives experienced a negative impact on their physical and emotional well-being. Previous studies have also found that chronic isolation of older adults was associated with cognitive decline and anxiety.9 , 10 Furthermore, family care and support normally provided in nursing homes like assistance with activities of daily living care, emotional support, and socialization is no longer possible.11, 12, 13 Also, it is known that alternative forms of communication between family and nursing home residents used during visiting restrictions like telephone, video calls, and e-mail are modest substitutes for in-person family care.5 , 14

On March 20, 2020, the Netherlands closed all visitation to all 115,000 nursing home residents.15 Although visiting restrictions are instituted to prolong the life of nursing home residents, they may detrimentally and disproportionately affect their quality of life, creating a dilemma between quantity of life versus quality of life. Given this dilemma, it is important to evaluate visiting restriction policies from different perspectives. It is particularly important to identify the perspectives of the people who are highly affected by the restrictions, like nursing home residents and their relatives. It is currently unclear if relatives support these restrictive policies, what detrimental effects do relatives think may be occurring for nursing home residents and for themselves, and are there unmet needs for residents and relatives. The aim of this study was to capture the perspectives on the COVID-19 nursing home visiting restrictions from relatives of nursing home residents. These results are imminently important to inform policy makers and nursing homes with regard to unmet needs and create best practices during and after visiting restrictions, especially considering the COVID-19 crisis is far from over, and nursing homes might need to prohibit visits again in the near future.

Methods

Study Design

This cross-sectional survey study was conducted between April 28, 2020 and May 3, 2020, which was 6 weeks after the Dutch government closed all nursing homes visitation due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since May 25, 2020, nursing homes are gradually opening to a limited number of visitors. It should be noted that in this period there was a shortage of personal protective gear for nursing home staff and visitors.16 , 17 This study was developed using the STROBE guidelines.18

Respondents

People were eligible to participate in this study if they were 18 years and older, had a family member or friend in a nursing home during the period of the visiting restrictions, and were able to read and write Dutch. Respondents were recruited via the Web site of a senior citizens’ union, nursing labor union V&VN, a dementia patient federation, and 2 national newspapers. The soliciting text explained the aim and relevance of this study. Potential respondents were asked to complete an online survey embedded in a direct link on the Web site.

Survey Development

The survey construction was based on a literature review search and multiple group discussions with a team of geriatricians, registered nurses, and physical therapists. The survey targeted 4 key areas: (1) communication access to residents, (2) potential adverse effects of visiting restrictions on residents and relatives, (3) potential protective effect of visiting restrictions on residents, and (4) important aspects for relatives during and after visiting restrictions (see Appendix for complete survey instrument). Each of the 4 key areas included multiple survey questions. The survey consisted of 5 Likert items (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree), 3 multiple-select questions, and 2 open-ended questions. In addition, key demographics were included.

Statistical Analyses

Results were presented as frequencies and percentages. Furthermore, using Likert items as the outcome variable, ordinal logistic regressions were performed with results expressed in proportional odds ratios. Variables included the backward stepwise selection procedure included age, sex, relation to nursing home resident, and urban or rural living. The assumption of proportional odds was tested for all models. The final model was based on independent variables having a P value less than .05. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis to systematically examine patterns in the written data.19 JW analyzed all written data, and DK and MvR each analyzed half of the data. Coding schemes were regularly discussed and compared in the research group.

Results

Participant Characteristics

From the 3316 survey respondents who started the survey, 1117 did not meet the eligibility criteria, and 202 were excluded because they did not fill in any survey question, resulting in 1997 respondents included in the analysis. Baseline characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Characteristics of Respondents (n = 1997)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1334 | 66.8 |

| Male | 461 | 23.1 |

| Missing data | 202 | 10.1 |

| Age in mean (range) | 60.1 | 20–97 |

| Missing data | 194 | 9.7 |

| Relation to nursing home resident | ||

| Partner | 183 | 9.2 |

| First-degree relative | 1190 | 64.6 |

| Other relative | 338 | 16.9 |

| Friend | 107 | 5.4 |

| Other | 78 | 3.9 |

| Missing data | 0 | 0.0 |

| Living area of respondent | ||

| Urban | 1085 | 54.4 |

| Rural | 713 | 35.6 |

| Missing data | 199 | 10.0 |

Communication Access to Nursing Home Residents

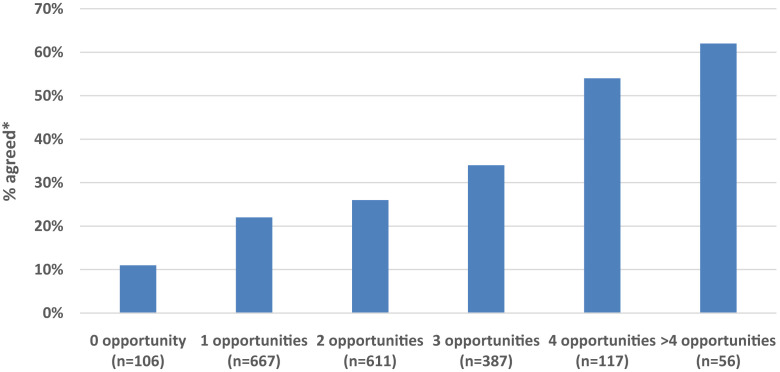

Table 2 shows that most frequently used means to stay in touch with nursing home residents were telephone (n = 1135) and video calling (n = 848). Respondents experienced most satisfaction when they had the possibility to stay in touch with nursing home residents by nurses informing them by telephone (44%), contact behind glass (40%), or contact outside maintaining distance (40%). Furthermore, satisfaction of communication access increased by the amount of possibilities available to respondents (see Figure 1 ).

Table 2.

Contact Possibilities, Usage, and Satisfaction of Relatives to Stay in Touch With Nursing Home Residents (n = 1994)

| n∗ | Satisfaction, %† | |

|---|---|---|

| Telephone | 1135 | 30 |

| Video calling | 848 | 33 |

| Informed via online patient record | 543 | 36 |

| Behind glass | 424 | 40 |

| Outside maintaining distance | 320 | 40 |

| Nurse informs me via telephone | 265 | 44 |

| Other | 196 | 32 |

| No opportunity | 185 | 15 |

Respondents could select multiple contact possibilities available to them.

Percentage of agreement on the statement “The contact possibilities available to me are sufficient to stay in touch with nursing home residents”.

Fig. 1.

Contact possibilities, satisfaction of relatives by the number of possibilities available to them (n = 1944). ∗Percentage of agreement on the statement “The contact possibilities available to me are sufficient to stay in touch with nursing home residents”.

Potential Adverse Effects of Visiting Restrictions on Residents and Relatives

Most relatives selected loneliness (76%), sadness (66%), and loss of quality of life (62%) as potential adverse effects on nursing home residents (see Table 3 ). Respondents specified in the “other” option that adverse effects also included increase of cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, insufficient personal care (eg, care of hair and nails), and especially for persons with dementia, alienation from their social network. The most selected adverse effect on relatives of nursing home residents was sadness (73%). Respondents specified in the “other” option that adverse effects on relatives included feelings of guilt, and no recognition of informal caregiver role.

Table 3.

Results of Multiselect Questions Regarding the Potential Adverse Effects of Visiting Restrictions on Nursing Home Residents and Their Relatives (n = 1942)

| Potential Adverse Effects on Nursing Home Residents, n (%) | Adverse Effects on Relatives of Nursing Home Residents, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | 1485 (76) | 298 (15) |

| Sadness | 1291 (66) | 1424 (73) |

| Loss of quality of life | 1212 (62) | 418 (21) |

| Fear | 677 (35) | 498 (26) |

| Physical complaints such as pain, physical functioning | 658 (34) | 94 (5) |

| Agitation | 425 (22) | 347 (18) |

| Safety | 352 (18) | 218 (11) |

| Loss of dignity | 351 (18) | 186 (10) |

| Loss of autonomy | 256 (13) | 219 (11) |

| Other | 196 (10) | 216 (11) |

Results are ordered by most selected potential adverse effects for nursing home residents.

Perspectives on the Protective Effect of Visiting Restrictions

Table 4 shows that most of the respondents (66.7%) agreed that visiting restrictions protected nursing home residents against COVID-19, less than half of the respondents agreed that visiting restrictions protected visitors (48.1%), and that the protective effect of visiting restrictions outweighed the adverse effects on well-being of nursing home residents and visitors (40.1%). Men were more likely than women to agree that the restrictions protected nursing home residents [odds ratio (OR) 1.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.19–1.76], visitors (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.15–1.70), and the protective effects outweighed the adverse effects of well-being (OR 1.50 95% CI 1.23–1.82). Being an older age was associated with greater odds of agreeing that the restrictions protected visitors (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.04) and the protective effects outweighed the adverse effects of well-being (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.02). Results of multivariable analysis can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 4.

Results of Likert Items on Perspectives of Relatives Regarding the Protective Effects of the Visiting Restrictions (n = 1997)

| Strongly Agree, n (%) | Agree, n (%) | Neutral, n (%) | Disagree, n (%) | Strongly Disagree, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restrictions are needed to protect nursing home residents | 494 (24.7) | 838 (42.0) | 358 (17.9) | 225 (11.3) | 82 (4.1) |

| Restrictions are needed to protect visitors | 318 (15.9) | 644 (32.2) | 432 (21.6) | 469 (23.5) | 134 (6.8) |

| Protective effect of restrictions outweigh the adverse effects | 278 (14.9) | 471 (25.2) | 422 (22.6) | 452 (24.2) | 247 (13.2) |

Important Aspects for Relatives During and after Visiting Restrictions

Respondents answered open-ended questions regarding their needs during visiting restrictions. Two themes of needs experienced during the period the government closed all nursing homes to visitation were revealed. First theme, provision of information. Respondents explained that they needed more information about the health and well-being of nursing home residents, and specific information from the nursing homes on what the visiting restrictions entail in their situation. Second theme, context-specific solutions. Respondents made clear that nursing homes should facilitate contact possibilities by for example the use of timetables or appointing a staff member as primary contact. Furthermore, nursing homes should provide more alternative contact possibilities like online technologies or a physical chat box in which people can communicate behind glass.

“We need more ways to stay in touch with my grandmother. For example, that we frequently can video call or call. That the nursing staff helps to establish a video call connection when she cannot. We also would like a container with glass in the middle so we can see each other in person.” (Quote of a relative)

Two themes of needs expected for when nursing homes start allowing a limited amount of visitors from outside nursing homes were revealed. First theme, protective measures. Respondents questioned the availability of personal protective gear to prevent transmission. In addition, they indicated testing visitors for COVID-19 should be possible. Second theme, safety protocols. Respondents ask for clear safety protocols for visitors, nursing home residents, and nursing home staff. Moreover, respondents would like to be involved in the process of designing these protocols to ensure their needs are included.

“I see that many people are reckless, for example not maintaining social distance. We need clear protocols so that safety is ensured. Checking for Corona symptoms, checking temperature at the entrance, walking routes, washing hands, and visits in a special room.” (Quote of a relative)

Discussion

Key Findings

This study provided insights into the perspectives of relatives of nursing home residents on the nursing home visiting restrictions during the COVID-19 crisis. Results showed that satisfaction of relatives of nursing home residents regarding communication access to nursing home residents differs per contact possibility available, and increases with the amount of possibilities available. In addition, according to relatives of nursing home residents, both nursing home residents and relatives experienced adverse effects on well-being because of visiting restrictions. However, there was no consensus between relatives of nursing home residents if the adverse effects on well-being outweigh the protective effect against the COVID-19. Nevertheless, they expressed various needs during visiting restrictions such as the need for more context-specific information, communication options, and safety protocols.

Relatives who stayed in contact with nursing home residents through nurses informing them via telephone, contact behind glass, or contact outside maintaining physical distance experienced most satisfaction of communication access to nursing home residents. Even though communicating with nursing home residents by telephone and video calls was more frequently used, respondents experienced less satisfaction thereof. This supports the idea that only telephone and video communication is a modest substitute for physical contact.5 , 14 What is surprising is that more satisfactions was experienced by nurses informing relatives via telephone than relatives engaging with nursing home residents themselves. A possible explanation might be that the use of communication devices for telephoning and video calling can be experienced as difficult for nursing home residents, or is hindered by impairments such as deafness, visual impairments, or dementia, while nurses might provide clearer information on the well-being of nursing home residents.

In addition, this study found that providing multiple possibilities to stay in contact with nursing home residents increased satisfaction. However, only a small proportion of study participants had access to more than 2 contact possibilities. These results imply more efforts should be made to facilitate more frequent and alternative contact possibilities available apart from telephone and video communication.

Furthermore, this study showed that most respondents were concerned the nursing home residents were experiencing loneliness, sadness, and decreased quality of life while respondents themselves were mainly experiencing sadness. These findings are consistent with previous studies who found that isolated older adults are at higher risk of depression and anxiety.8 , 20 Other studies found that social isolation of older adults is also associated with cardiovascular and cognitive decline.9 , 10 , 21

Adverse effects on health and well-being seem to be a prevalent argument in the debate on discarding visiting restrictions. Even more so because many nursing home residents are in their end-of-life phase, and prefer quality of life over quantity of life.22 Yet, this study showed that there is a dichotomy in opinions of relatives of nursing home residents if visitors should be allowed back in nursing homes. An interesting finding is that male sex and being at older age is associated with higher agreement on the potential protective effects of visiting restrictions. A possible explanation for older people having more positive attitudes regarding the protective effects of visiting restrictions could be that older people themselves have a higher risk of severe illness from COVID-19. Nevertheless, these results imply policy makers have to find a balance between infection prevention and opening up nursing homes for visitors.

Even though opinions regarding visiting restriction differed, this study identified several needs experienced during visiting restrictions. This study found that needs were provision of information and alternative ways for staying in touch with nursing home residents. These findings are in line with other studies that emphasized the importance of communication among nursing home staff, nursing home residents, and relatives.8 , 23, 24, 25 When nursing homes start allowing a limited amount of visitors, needs concern protective measures like personal protective gear, and safety protocols. These needs corroborate with strategies suggested by key public health organizations specialized in infection control.6 , 7

Considering the challenges in communication access to nursing home residents, the adverse effects of visiting restrictions, and the importance of family caregiving in nursing homes,13 future research should focus on balanced policies allowing visitors back in nursing homes, while accounting for COVID-19 risk reduction. Verbeek et al.26 piloted allowing visitors back in 26 Dutch nursing homes using a comprehensive visiting guideline. Results showed that all nursing homes supported the added value of personal contact, and although more research is needed on long-term effects, allowing visitors was not associated with an increase of COVID-19 infections.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge this is the first study that gives insight into perspectives of relatives regarding visiting restrictions in nursing homes and includes a large sample size of relatives of nursing home residents. However, a limitation of this study was the use of a convenience sample, which limits the generalizability of the conclusions. Convenience samples may cause sampling bias where one group may be overrepresented while another group is underrepresented, causing sampling error. Given the large sample size included in this study, convenience sampling enables us to see trends in data.

Conclusions and Implications

Findings of this study can help understand how nursing home residents and their relatives experience visiting restrictions. Nursing home residents and their relatives can experience adverse effects on well-being because of visiting restrictions during COVID-19. However, there is no consensus between relatives of nursing home residents if the adverse effects on well-being outweigh the protective effect against the COVID-19. Nevertheless, they expressed various needs during visiting restrictions like improvement of communication between nursing home staff and relatives, and facilitating possibilities for nursing home residents to stay in touch with their relatives. Incorporating the needs of relatives of nursing home residents in policy development might increase support for visiting restrictions and decrease some of the adverse effects because of isolation.

During a period of visiting restrictions, it is important to strengthen the communication between nursing home staff and relatives of nursing home residents. Timely communicate information on what the visiting restrictions entail, and frequently inform relatives on health, well-being and care planning of nursing home residents. Also, communication between nursing home residents and their relatives is vital. Facilitate regular communication through contact possibilities such as phone calls or video calls, and provide alternative forms of communication such as meeting each other behind glass or outside while maintaining physical distance. Simard and Volicer27 provide 9 practical ideas for families to communicate with nursing home residents such as sending cards and simulated presence therapy. When a limited number of visitors are allowed at nursing homes, provide clear safety protocols for nursing home residents, visitors, and staff. In addition, personal protective gear should be provided for nursing home staff, nursing home residents, and their relatives.

Acknowledgments

We thank the senior citizens' union PCOB, Nursing labor union V&VN, and the Dutch dementia patient federation for their valuable contribution in spreading the survey and collecting survey data.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.This work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (NWO-ZonMw Veni, 091.619.060), and the Ben Sajet Centrum Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Appendix. [Translated from Dutch]

Page 1

Since March 20 the government implemented visiting restrictions for all Dutch nursing homes, which prohibits all visits at nursing homes. These regulations are implemented to protect nursing home residents, their relatives, and nursing home staff against the coronavirus. With this survey we would like to know your experiences regarding the visiting restrictions, the way you stay in touch with nursing home residents, and what are your needs.

The survey takes approximately 5 minute to complete; however, can take more time, depending on your response. All answers will be anonymized and handled with confidentiality. This online survey is according to the Dutch General Data Protection Regulation (Dutch: Algemene Verordening Gegevensbescherming).

[Q 1]

Do you have a family member or friend in a nursing home at the moment?

-

1.

Yes

-

2.

No

[Q 1 and 2.]

You indicated not to have a family or friend in a nursing home at the moment. This survey targets respondents who have a family or friend in a nursing home at the moment. You don't meet the target population of this survey. We would like to thank you for your interest and time. You will be redirected to the Web site you entered this survey from.

[Q 2]

What is your relation to the nursing home resident?

-

1.

Partner

-

2.

Parent

-

3.

Child

-

4.

Other family member

-

5.

Friend

-

6.

Other

[Q 2 and 6.]

Please clarify

Page 2

Visiting restrictions are implemented to protect nursing home residents, their relatives, and nursing home staff against the coronavirus. Older adults have higher risk for complications and mortality of the coronavirus. Because older adults live closely to each other in nursing homes they become vulnerable to spread of the virus. By prohibiting all visits from outside nursing homes, the spread of the coronavirus will be prevented as much as possible. The following statements concern your feelings of safety and that of nursing home residents

[Q 3]

The visiting restrictions are needed to protect nursing home residents against the coronavirus.

-

1.

Strongly agree

-

2.

Agree

-

3.

Neutral

-

4.

Disagree

-

5.

Strongly disagree

[Q 4]

The visiting restrictions are also needed to protect relatives of nursing home residents against the coronavirus.

-

1.

Strongly agree

-

2.

Agree

-

3.

Neutral

-

4.

Disagree

-

5.

Strongly disagree

At this moment there are many information sources that provide information about the visiting restrictions. The following statements concern your feeling of being informed.

[Q 5]

I am informed sufficiently about why the visiting restrictions are implemented.

-

1.

Strongly agree

-

2.

Agree

-

3.

Neutral

-

4.

Disagree

-

5.

Strongly disagree

[Q 5 clarification option]

Please clarify

Page 3

Many nursing homes try to maintain contact with nursing home residents by different forms of communication. The following questions relate to how you stay in touch with nursing home residents.

[Q6]

In what way you stay in touch with nursing home residents? Multiple answers are possible.

-

1.

I do not have a possibility to stay in touch

-

2.

Telephone

-

3.

Video calling

-

4.

The nursing home provides the opportunity to make visits behind glass.

-

5.

The nursing home provides the opportunity to make visits outside maintaining physical distance

-

6.

Nurses keep me informed by telephone

-

7.

Nurses keep me informed by the online patient record

-

8.

Other

[Q6 and 8]

Please clarify

The contact opportunities provided are sufficient to stay in touch with nursing home residents.

-

1.

Strongly agree

-

2.

Agree

-

3.

Neutral

-

4.

Disagree

-

5.

Strongly disagree

[Q6 clarification option]

Please clarify.

The visiting restrictions can have negative effects on nursing home residents and you as relatives of nursing home residents. The following statements concern the potential affects you see for nursing home residents and for yourself.

Page 4

[Q7]

The visiting restrictions have the following adverse effects on nursing home residents. Multiple answers are possible.

-

1.

Fear

-

2.

Quality of life

-

3.

Loneliness

-

4.

Safety

-

5.

Dignity

-

6.

Autonomy

-

7.

Agitation

-

8.

Sadness

-

9.

Physical complaints (eg, pain, decrease in physical functioning)

-

10.

None

-

11.

Other

[Q7 and 11]

Please clarify.

The visiting restrictions have the following adverse effects on myself. Multiple answers are possible.

-

1.

Fear

-

2.

Quality of life

-

3.

Loneliness

-

4.

Safety

-

5.

Dignity

-

6.

Autonomy

-

7.

Agitation

-

8.

Sadness

-

9.

Physical complaints (eg, pain, decrease in physical functioning)

-

10.

None

-

11.

Other

[Q8 and 11]

Please clarify

Page 5

The following questions concern the potential protective effect for the coronavirus of visiting restrictions.

[Q9]

I think protecting nursing home residents, family, and others from the coronavirus outweighs not being able to visit nursing home residents and the potential negative effects thereof.

-

1.

Strongly agree

-

2.

Agree

-

3.

Neutral

-

4.

Disagree

-

5.

Strongly disagree

[Q9 clarification option]

Please clarify

At this moment the visiting restrictions still apply to all visits of nursing home residents. Even though unclear when, in the future a minimum of number of visitors might be allowed. The following questions concern your needs experienced now and for the future when nursing homes slowly open up.

[Q10]

What are you needs now while all visits are prohibited for nursing home residents?

[Q11]

What do you need when nursing homes start allowing (a minimum number) of visitors?

Page 6

These were all survey questions. We would like you to provide your personal information. All information will be handled confidentially.

[Q12]

What is your age in years?

[Q13]

What is your sex?

-

1.

Female

-

2.

Male

[Q14]

In which province do you live?

-

1.

Groningen

-

2.

Friesland

-

3.

Drenthe

-

4.

Overijssel

-

5.

Flevoland

-

6.

Gelderland

-

7.

Utrecht

-

8.

Noord-Holland

-

9.

Zuid-Holland

-

10.

Zeeland

-

11.

Noord-Brabant

-

12.

Limburg

[Q15]

In what kind of area do you live?

-

1.

Urban living

-

2.

Rural

This is the end of the survey. Thank you for your cooperation.

After closing this page you will be redirected to the Web site you entered this survey from.

Supplementary Table 1.

Result of Backward Stepwise Selection Method, Ordinal Logistic Regression of Likert Items on Perspectives on the Protective Effect of Visiting Restrictions

| Odds Ratio∗ | P Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visiting restrictions protect nursing home residents | |||

| Sex male | 1.45 | <.001 | 1.19–1.76 |

| Visiting restrictions protect visitors | |||

| Sex male | 1.40 | .001 | 1.15–1.70 |

| Age in years | 1.03 | <.001 | 1.02–1.04 |

| The protective effects outweigh the adverse effects on well-being | |||

| Sex male | 1.50 | <.001 | 1.23–1.82 |

| Age in years | 1.02 | <.001 | 1.01–1.02 |

Men were more likely than women to agree that the restrictions protected nursing home residents, visitors, and the protective effects outweighed the adverse effects of well-being. Older adults had greater odds of agreeing that the restrictions protected visitors and the protective effects outweighed the adverse effects of well-being.

Proportional odds ratios of falling in a higher category (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) calculated from ordinal logistic regression.

References

- 1.Applegate W.B., Ouslander J.G. COVID-19 presents high risk to older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:681. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L., He W., Yu X., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: Characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect. 2020;80:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niu S., Tian S., Lou J., et al. Clinical characteristics of older patients infected with COVID-19: A descriptive study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;89:104058. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.British Geriatrics Society Managing the COVID-19 pandemic in care homes. British Geriatrics Society Good Practice Guide. 2020;3:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson P.M., Szanton S.L. Nursing homes and COVID-19: We can and should do better. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:2758–2759. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Infection prevention and control guidance for long-term care facilities in the context of COVID-19; 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331508/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPC_long_term_care-2020.1-eng.pdf Available at:

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Key strategies to prepare for COVID-19 in long-term care facilities; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/long-term-care-strategies.html Available at:

- 8.McCleary L. Impact of SARS visiting restrictions on relatives of long-term care residents. Journal of Social Work in Long-Term Care. 2008;3:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhong B.L., Chen S.L., Conwell Y. Effects of transient versus chronic loneliness on cognitive function in older adults: Findings from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24:389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerst-Emerson K., Jayawardhana J. Loneliness as a public health issue: The impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1013–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis L., Buckwalter K. Family caregiving after nursing home admission. J Ment Health Aging. 2001;7:361–379. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaugler J.E. Family involvement in residential long-term care: A synthesis and critical review. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9:105–118. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331310245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlaudecker J.D. Essential family caregivers in long-term care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:983. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trabucchi M., De Leo D. Nursing homes or besieged castles: COVID-19 in northern Italy. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:387–388. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30149-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cenraal Bureau voor Statistiek Aantal bewoners van verzorgings- en verpleeghuizen 2019; 2019. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/maatwerk/2020/13/aantal-bewoners-van-verzorgings-en-verpleeghuizen-2019 Available at:

- 16.V&VN. Tekorten aan maskers; 2020. https://www.venvn.nl/nieuws/peiling-v-vn-tekorten-maskers-houden-aan-psychische-druk-hoog/ Available at:

- 17.Rijksoverheid Het corona virus en peroonlijke beschermingsmiddelen. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/coronavirus-covid-19/zorg/beschermingsmiddelen Available at:

- 18.Vandenbroucke J.P., von Elm E., Altman D.G., et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santini Z.I., Jose P.E., York Cornwell E., et al. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): A longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e62–e70. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armitage R., Nellums L.B. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e256. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsson I.N., Runnamo R., Engfeldt P. Medication quality and quality of life in the elderly, a cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:95. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hado E., Friss Feinberg L. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, meaningful communication between family caregivers and residents of long-term care facilities is imperative. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32:410–415. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1765684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hart J.L., Turnbull A.E., Oppenheim I.M., et al. Family-centered care during the COVID-19 era. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e93–e97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banskota S., Healy M., Goldberg E.M. 15 Smartphone apps for older adults to use while in isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21:514–525. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verbeek H., Gerritsen D.L., Backhaus R., et al. Allowing visitors back in the nursing home during the COVID-19 crisis: A Dutch national study into first experiences and impact on well-being. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:900–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simard J., Volicer L. Loneliness and isolation in long-term care and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:966–967. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]