Abstract

Background

The Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR), the first nation-wide registry of renal biopsies in Japan, was established in 2007, and expanded to include non-biopsy cases as the Japan Kidney Disease Registry (J-KDR) in 2009. The J-RBR/J-KDR is one of the biggest registries for kidney diseases. It has revealed the prevalence and distribution of kidney diseases in Japan. This registry system was meant to be revised after 10 years.

Methods

In 2017, the Committees of the Japanese Society of Nephrology started a project for the revision of the J-RBR/J-KDR. The revised system was designed in such a way that the diagnoses of the patients could be selected from the Diagnosis Panel, a list covering almost all known kidney diseases, and focusing on their pathogenesis rather than morphological classification. The Diagnosis Panel consists of 22 categories (18 glomerular, 1 tubulointerstitial, 1 congenital/genetical, 1 transplant related, and 1 other) and includes 123 diagnostic names. The items for clinical diagnosis and laboratory data were also renewed, with the addition of the information on immunosuppressive treatment.

Results

The revised version of J-RBR/J-KDR came into use in January 2018. The number of cases registered under the revised system was 2748 in the first year. The total number of cases has reached to 43,813 since 2007.

Conclusion

The revised version 2018 J-RBR/J-KDR system attempts to cover all kidney diseases by focusing on their pathogenesis. It will be a new platform for the standardized registration of kidney biopsy cases that provides more systemized data of higher quality.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10157-020-01932-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Renal biopsy, Pathology, Registry

Introduction

The Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR), the first nation-wide web-based registry of renal biopsies in Japan, was established in 2007 [1]. The renal biopsy is the gold standard for the classification and diagnosis of kidney diseases, and it provides essential information for managing the condition [2,3]. It can also provide us with information on the incidence and distribution of kidney diseases. From the 1980s, the results of renal biopsy registry studies have been reported from all over the world [4–7].

In 2009, the Japan Kidney Disease Registry (J-KDR) which includes non-biopsy cases in addition to those registered in the J-RBR was started [8]. Thereafter, the kidney diseases that do not require renal biopsy, such as polycystic kidney disease and congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT), could also be registered. As of December 2017, 143 nephrology centers have joined the J-RBR/J-KDR, which includes 40,369 patients in total: 37,215 biopsy cases and 3154 non-biopsy cases [9]. The cross-sectional data from the J-RBR/J-KDR have revealed the demographics of kidney diseases in Japan [10–18] and provided fundamental knowledge for ancillary studies [19–24].

In the original J-RBR/J-KDR 2007 system, diagnosis of the patients consists of three components: (i) a clinical diagnosis, (ii) a histological diagnosis by pathogenesis, and (iii) a histological diagnosis by histopathology (Online Resource 1) [1]. It followed the classification of glomerular diseases that was originally proposed in the 1980s by the World Health Organization (WHO) and revised in the 1990s [25,26]. This classification describes histopathological patterns of glomerular injury but does not encompass its etiology. Recently, Sethi et al. suggested a pathogenesis-based classification for glomerulonephritis [27], however, that did not include major proteinuric glomerular diseases, such as minimal change disease (MCD), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), membranous nephropathy (MN), and tubulointerstitial diseases. Therefore, it was necessary to establish a comprehensive classification, which covers all categories of biopsy-proven kidney diseases based on their pathogenesis.

The Committee for Renal Biopsy and Disease Registry of the Japanese Society of Nephrology revised the J-RBR/J-KDR system to establish a more practical histopathological grouping and classification of the kidney diseases.

Materials and methods

Participants and data collection

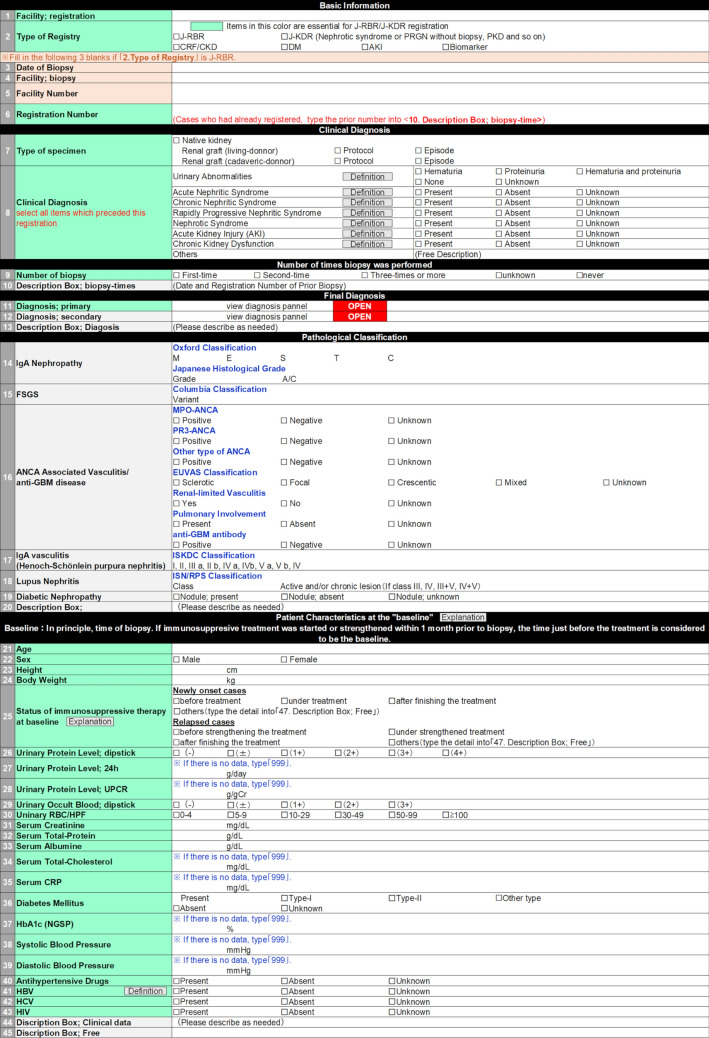

The J-RBR/J-KDR collects clinical data and pathological diagnoses of patients from the collaborative institutes in Japan. These data are registered via the web page of the J-RBR/J-KDR (Fig. 1) utilizing the system of Internet Data and Information Center for Medical Research (INDICE) in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN). The essential points of this revision are described below.

Fig. 1.

The main page for registration with J-RBR/J-KDR. Definitions: Urinary Abnormalities, hematuria and/or proteinuria observed prior to registration; Acute Nephritic Syndrome, A syndrome characterized by abrupt onset of macroscopic hematuria, proteinuria, hypertension, decreased glomerular filtration and retention of sodium and water [26]. Chronic Nephritic Syndrome, slowly developing renal failure accompanied by proteinuria, hematuria, and hypertension [26]. Rapidly Progressive Nephritic Syndrome, rapidly progressing renal failure within several weeks to several months that is associated with urinary findings, such as proteinuria, hematuria, red blood cell casts, and granular casts indicating glomerulonephritis [28]. Nephrotic Syndrome, both massive proteinuria (≥ 3.5 g/day) and hypoalbuminemia (serum albumin ≤ 3.0 g/dL) [29]. Acute Kidney Injury, (1) Increase serum Creatinine ≥ 0.3 mg/dL within 48 h, (2) Increase serum Creatinine ≥ 1.5 times baseline within 7 days, (3) Urine volume < 0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 h [30]. Chronic Kidney Dysfunction, Cases with eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.75m2 for more than 3 months [31]. Pulmonary involvement of ANCA-associated vasculitis/anti-GBM disease, abnormality in chest X-ray except infection or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), alveolar hemorrhage and interstitial pneumonia. HBV, cases with prior infection or latent infection are considered as “present”. Explanations: *Patient characteristics at the “baseline”, If immunosuppressive treatment was started or strengthened more than 1 month prior to biopsy, the time of biopsy is considered to be the baseline. If immunosuppressive treatment was started or strengthened within 1 month prior to biopsy but the data just before the treatment were not available, the time of biopsy is considered to be the baseline. † Status of immunosuppressive therapy at baseline, Select the status of immunosuppressive treatment at the time of “baseline”. “after finishing the treatment” indicates the status without any immunosuppressive treatment. J-RBR Japan Renal Biopsy Registry, J-KDR Japan Kidney Disease Registry, RPGN rapid progressive glomerulonephritis, CRF chronic renal failure, CKD chronic kidney disease, DM diabetes mellitus, AKI acute kidney injury, FSGS focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, ANCA anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, MPO myeloperoxidase, PR3 proteinase 3, EUVAS the European Vasculitis Study Group, GBM glomerular basement membrane, ISKDC the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children, ISN/RPS the International Society of Neurology and the Renal Pathology Society, UPCR urinary protein creatinine ratio, RBC red blood cell, HPF hyper power field, CRP C-reactive protein, NGSP the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program, HBV hepatitis B virus, HCV hepatitis C virus, HIV human immunodeficiency virus

Clinical diagnoses

The clinical diagnoses of the patients are selected from the list shown in Fig. 1, which includes urinary abnormalities, acute nephritic syndrome, chronic nephritic syndrome, rapidly progressive nephritic syndrome, nephrotic syndrome, acute kidney injury (AKI), chronic kidney dysfunction, and others. These clinical diagnoses are defined by current related guidelines or WHO classification [26,28–31]. The revised system of the J-RBR/J-KDR 2018 allows the registration of multiple clinical diagnoses for each case in case of overlapping clinical symptoms e.g., an MCD case demonstrated with acute kidney injury. A new category for urinary abnormalities was added to describe the patients whose biopsy was followed by asymptomatic mild hematuria and/or proteinuria.

Pathological diagnoses

-

Overview of the diagnosis panel

The pathological diagnoses for registration are selected from the “Diagnosis Panel” in the web page of J-RBR/J-KDR. Clicking the button of the panel on the web page opens the list of the diagnoses as shown in Table 1. It is the main part of this revision, and constructed based on two principles. First, we tried to cover all the diagnostic names of kidney diseases including the rare ones. The panel contains 22 categories of renal diseases: 18 glomerular, 1 tubulointerstitial, 1 congenital/genetical, 1 transplant related, and 1 other, including 123 diagnostic names. In the registration process, the most appropriate diagnosis should be selected from the panel as principal diagnosis. For complex cases with multiple diagnoses, such as lupus nephritis with findings of diabetic nephropathy, additional panels for secondary diagnosis are set on the web page of the J-RBR/J-KDR.

Second, the diagnostic names of the kidney diseases will be registered based on their pathogenesis rather than morphology. For example, a patient with MN induced by hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is registered into the category of infection-related glomerulonephritis and not MN.

Additional information, such as the name of specific drug that provoked drug-induced secondary MCD, may be entered in the <13. Description Box; Diagnosis> in the main page of the J-RBR/J-KDR registration (Fig. 1). This panel was reviewed by the Japanese Renal Pathology Society.

Detailed pathological classification (optional)

Table 1.

List of the diagnoses in the Diagnosis Panel of the J-RBR/J-KDR

| 1. IgA nephropathy |

| 1) Primary IgA nephropathy |

| 2) Secondary IgA nephropathy |

| (1) Hepatological disorder* |

| (2) Others* |

| 2. Minimal change disease (MCD) |

| 1) Primary (idiopathic) MCD |

| 2) Secondary MCD |

| (1) Malignancy* |

| (2) Drug-induced* |

| (3) Others* |

| 3. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) |

| 1) Primary (idiopathic) FSGSa |

| 2) Secondary FSGS |

| (1) Familial/genetic* |

| (2) Obesity |

| (3) Low birth weight* |

| (4) Hypertension/arteriosclerosis* |

| (5) Drug-induced* |

| (6) Others* |

| 4. Membranous nephropathy |

| 1) Primary (idiopathic) Membranous nephropathy |

| 2) Secondary Membranous nephropathy |

| (1) Malignancy* |

| (2) Drug-induced* |

| (3) Infection*,b |

| (4) Others* |

| 5. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) |

| 1) Primary MPGNc |

| (1) Type I MPGN |

| (2) Type III MPGN* |

| 2) Secondary MPGNd |

| (1) Secondary MPGN* |

| (2) Others* |

| 6. C3 glomerulopathy |

| 1) Dense deposit disease (DDD) |

| 2) C3 glomerulonephritis |

| 7. Vasculitis syndromee |

| 1) ANCA-associated vasculitis |

| (1) Microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) |

| (2) Granulomatous polyangiitis (GPA) |

| (3) Eosinophilic granulomatous polyangiitis (EGPA) |

| (4) Drug-induced* |

| (5) Unclassified* |

| 2) Anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) diseasef |

| 3) IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis)g |

| 4) Polyarteritis nodosa |

| 5) Others*,h |

| 8. Nephropathy associated with connective tissue diseases |

| 1) Lupus nephritisi |

| 2) Sjögren syndrome |

| (1) Tubulointerstitial nephritis |

| (2) Others* |

| 3) Rheumatoid arthritis*,j |

| 4) Systemic sclerosis |

| (1) Thrombotic microangiopathy |

| (2) Others* |

| 5) Others* |

| 9. Infection related glomerulonephritis |

| 1) Poststreptococcal acute glomerulonephritis |

| 2) Staphylococcus associated glomerulonephritis* |

| 3) HBV-associated nephropathy |

| (1) Membranous nephropathy |

| (2) Others* |

| 4) HCV-associated nephropathy |

| (1) MPGN |

| (2) Others* |

| 5) Parvovirus related glomerulonehritis |

| 6) HIV associated nephropathy |

| 7) Others* |

| 10. Other glomerulonephropathies |

| 1) IgM nephropathy |

| 2) C1q nephropathy |

| 3) Others* |

| 11. Hypertension/arteriosclerosis |

| 1) Nephrosclerosis |

| (1) Essential hypertension/arteriosclerosis |

| (2) Malignant hypertension |

| 2) Choresterol crystal embolization |

| 3) Others*,k |

| 12. Thrombotic microangiopathy(TMA)・endothelial injury |

| 1) Shiga toxin-production E coli hemolytic uremic syndrome (STEC-HUS) |

| 2) Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) |

| 3) Preeclampsia |

| 4) Drug-induced* |

| 5) Others* l |

| 13. Diabetic nephropathy |

| 1) Diabetic nephropathy |

| 14. Nephropathies with altered lipid metabolism |

| 1) Lipoprotein glomerulopathy |

| 2) LCAT deficiency |

| 3) Others* |

| 15. Paraprotein-related kidney disesasem |

| 1) Monoclonal immunoglobulin deposit disease (MIDD) |

| (1) Light chain deposition disease (LCDD) |

| (2) Heavy chain deposition disease (HCDD) |

| (3) Light and heavy chain deposition disease (LHCDD) |

| 2) Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits (PGNMID)n |

| 3) Cast nephropathy* |

| 4) Others* |

| 16. Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis |

| 1) Cryoglobulinemic vasculitiso |

| (1) Hematological/lymphoproliferative disorders* |

| (2) Others/unknown etiology* |

| 17. Nephropathies with organized deposit |

| 1) Immunotactoid glomerulopathy |

| 2) Fibrillary glomerulonephritis |

| 3) Fibronectin glomerulopathy |

| 4) Collagenofibrotic nephropathy |

| 5) Others* |

| 18. Renal amyloidosis |

| 1) AA amyloidosis* |

| 2) AL amyloidosis* |

| 3) Other type of amyloidosis*,p |

| 19. Congenital/genetic |

| 1) Congenital nephrotic syndromeq |

| 2) Alport syndrome |

| 3) Thin basement membrane disease |

| 4) Fabry disease |

| 5) Renal disease associated with mitochondrial cytopathy |

| 6) Autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease (ADTKD): including medullary cystic kidney disease (MCKD) |

| 7) Nephronophthisis/nephronophthisis-associated ciliopathies |

| 8) Polycystic kidney disease |

| (1) Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) |

| (2) Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) |

| (3) Others |

| 9) Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) |

| (1) Syndromic CAKUT |

| (2) Non-syndromic CAKUT |

| 10) Nail-patella syndrome/LMX1B associated nephropathy |

| 11) Others* |

| 20. Tubulointerstitial nephropathies |

| 1) Tubulointerstitial nephritis |

| (1) Drug-induced* |

| (2) IgG4-related kidney disease |

| (3) Sarcoidosis |

| (4) Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome |

| (5) Others*,r |

| (6) Unknown |

| 2) Acute tubular necrosis |

| 3) Others* |

| 21. Transplant kidney |

| 1) Transplant rejection |

| (1) Hyperacute rejection |

| (2) Acute rejection |

| ① Acute antibody mediated rejection |

| ② Acute T-cell mediated rejection |

| (3) Chronic rejection |

| ① Chronic antibody mediated rejection |

| ② Chronic T-cell mediated rejection |

| (4) Others* |

| 2) Drug-induced graft injury |

| (1) Calcineurin inhibitor induced nephropathy |

| (2) Others* |

| 3) Transplant related infection |

| (1) BK virus |

| (2) Adenovirus |

| (3) Epstein–Barr viruss |

| (4) Cytomegalovirus |

| (5) Others* |

| 4) Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) |

| 5) No specific findings |

| 6) Others* |

| 22. Others |

| 1) No specific abnormalities |

| 2) Others* |

| 3) Undiagnosable* |

J-RBR Japan Renal Biopsy Registry, J-KDR Japan Kidney Disease Registry, ANCA anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, HBV hepatitis B virus, HCV hepatitis C virus, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, LCAT lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase

*Describe the details in the < 13. Description Box; Diagnosis > in the main page of the registration for the J-RBR/J-KDR (Fig. 1).

aDescribe the Columbia classification in < 15. FSGS > in the main web page (Fig. 1)

bCases related to HBV or HCV should be registered in 9. Infection related glomerulonephritis

cMPGN type II (DDD) should be registered in 6. C3 glomerulopathy

dCases related to HBV or HCV should be registered in 9. Infection related glomerulonephritis

eIf the patient has other underlying diseases, e.g., systemic sclerosis, the details should be described in < 13. Description Box; Diagnosis > in the main web page (Fig. 1). ANCA-negative ANCA associated vasculitis should also be categorized into MPA, GPA or EGPA

fDescribe the data about antibodies/pathological classifications into < 16. ANCA Associated Vasculitis/anti-GBM disease > in the main web page (Fig. 1)

gDescribe the pathological classification into < 17. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis > in the main web page (Fig. 1)

hCases with cryoglobulinemic vasculitis should be registered in 16. Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis

iDescribe the pathological classification in < 18. Lupus Nephritis > in the main web page (Fig. 1)

jCases with membranous nephropathy or amyloidosis should be registered into their distinct categories

kCases with FSGS lesion should be categorized into secondary FSGS

lTMA associated with systemic sclerosis should be categorized into 8. Nephropathy associated with connective tissue diseases

mCases with amyloid deposition should be registered in 18. Renal amyloidosis

nDescribe the subtype of immunoglobulin in < 13.Description Box; Diagnosis > in the main web page (Fig. 1)

oCases with the infectious etiologies, such as HCV, should be categorized into 9. Infection related glomerulonephritis. Cases with the etiologies of connective tissue diseases such as SLE, should be categorized into 8. Nephropathy associated with connective tissue diseases. In these cases, describe the information on cryoglobulinemia in < 13. Description Box; Diagnosis > in the main web page (Fig. 1)

pCases which do not have any information about AA/AL should also be registered to 3) Other type of amyloidosis in 18. Renal amyloidosis

qDescribe pathological diagnosis in < 13.Description Box; Diagnosis > in the main web page (Fig. 1) if available

rCases who associated with any infection should be registered to 7) Others in 9. Infection related glomerulonephritis

sCases with Epstein-Barr virus related PTLD should be registered in PTLD

In this revision, we added more items for detailed pathological classification of several glomerular diseases, such as the Oxford Classification [32–34] and Japanese Histological Grade [35] for IgA nephropathy, the Columbia Classification for FSGS [36], the International Society of Neurology and the Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) classification for Lupus nephritis [37], the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children (ISKDC) classification for Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis [38], and the European Vasculitis Study Group (EUVAS) classification for ANCA-associated vasculitis [39].

Clinical data

-

Physical measurements and laboratory data

The revised system collects baseline clinical data (Fig. 1). The baseline is defined in the next section. The clinical variables include patient characteristics and physical measurements (age, sex, height, body weight, and systolic/diastolic blood pressure), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, infection of HBV, hepatitis C virus, or human immunodeficiency virus), urinary findings (qualitative testing for urinary protein, occult blood, and red blood cells, and quantitative measurement of urinary protein creatinine ratio and daily proteinuria), and blood test findings (serum creatinine, total protein, albumin, total cholesterol, CRP, and HbA1c). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is calculated from the patient’s age, sex, and serum creatinine level using the equations for Japanese children [40] and adults [41] at the time of analysis.

Treatment status of the “baseline”

In patients who received immunosuppressive treatment before biopsy, laboratory data at biopsy may be modified by the treatment. Information on the treatment status including whether the case is a new onset one or relapsed one will also be collected. The “baselines” for collecting clinical data are defined as follows (Fig. 1). Regarding the cases in which immunosuppressive treatment started or strengthened within 1 month prior to biopsy, the time just before the initiation of treatment is considered to be the baseline. In the cases in which immunosuppressive treatment started or strengthened more than 1 month prior to biopsy, the time of biopsy is considered as the baseline. In the cases in which immunosuppressive treatment started or strengthened within 1 month prior to biopsy but the data just before the treatment were not available, the time of biopsy is considered to be the baseline.

Results

The revised system of J-RBR/J-KDR came into use in January 2018. As of December 2018, the number of cases registered under the revised system had reached 2748 in the first year from 146 facilities. The total number of the cases registered in the J-RBR/J-KDR had reached 43,813 from the beginning of J-RBR in 2007.

Discussion

The J-RBR/J-KDR is a nationwide web-based registry in Japan, which has been conducted for more than 10 years, and it is one of the biggest registries for patients with kidney diseases including biopsy cases. We revised its registration system in 2018 with several strengths.

Clinical diagnoses that can represent the clinical status of the patients

The clinical diagnoses in the revised system enable to describe the clinical status of the patients more accurately based on the following modifications. First, the revised J-RBR/J-KDR allows the selection of all clinical diagnoses that are appropriate for the patients from the 8 listed items. Although the clinical indications for kidney biopsy vary [6], we sometimes experience patients who have multiple clinical symptoms that lead to biopsy. For example, 20–30% of the patients with MCD were reported to have demonstrated AKI [42]. If only one clinical diagnosis is registered in such cases, both the clinical diagnoses, nephrotic syndrome and AKI, could be underestimated. Second, the items indicating abnormalities in urinalysis were added. In Japan, a nationwide annual health examination program including urinalysis screening for all community residents has been going on for over 40 years [43]. It enables early detection of urine abnormalities and early referral to a nephrologist, and it is possible that a substantial number of the patients have undergone renal biopsy due to asymptomatic hematuria and/or proteinuria. Therefore, the revised J-RBR/J-KDR 2018 can describe clinical features of such patients.

Classification of kidney diseases and the structure of their registry system

For kidney diseases, the classification system should meet the following requirements: (a) clinically significant, useful, and therapeutically relevant, (b) based on pathogenesis within current knowledge, (c) easy to use and morphologically reproducible and (d) able to provide the information for prognosis [44]. Although the terminology of kidney diseases has been mainly based upon morphology, the pathogenesis of kidney diseases has been gradually revealed in recent decades. For example, membranous proliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) has been recognized as a pattern of glomerular injury and indicates a grouping of the patients who share common light microscopic findings. Nowadays, the cases with dysregulation of the alternative pathway of complement in MPGN are subdivided into C3 glomerulopathy [45]. Considering these advances, a classification based on etiology and pathogenesis is more desirable [44].

In addition, the value of a registry depends on its data quality, clarity of registration method, and ease of using the collected data [46]. The WHO classification [25,26], which was the fundamental concept behind the original J-RBR/J-KDR 2007 system, embodies the idea that the pathology of kidney diseases should be comprehensively interpreted with the integration of clinical, histopathological, and pathognomonic diagnoses. However, this classification was basically weighted in favor of morphology, not pathogenesis. Further, this complicating method made difficulty in data aggregation and not all diagnoses are suitable for being expressed by this method (e.g., MCD or diabetic nephropathy). In this revised system, the most appropriate diagnosis for the patients can be selected from the diagnosis panel, and this simple method will provide high reproducibility in registration.

Clinical data collection with the information of treatment status

Most of registries for kidney diseases collect the clinical data at the time of biopsy. However, it is difficult to interpret the laboratory data of patients without information on the treatment status. For example, we cannot distinguish the patients who demonstrated non-nephrotic range proteinuria from those who showed the improvement in nephrotic syndrome as a result of immunosuppressive treatment from their laboratory data alone. The revised J-RBR/J-KDR 2018 collects the information whether the laboratory data were collected before or after starting the immunosuppressive treatment. In this revision, based on these status, different “baselines” are defined for each case and it will provide more reliable data to describe the laboratory features of kidney diseases.

Problems requiring further discussion

The revised J-RBR/J-KDR 2018 system has several points that require further discussion. First, the borderline between the terms, “Primary (idiopathic)” and “Secondary,” in the glomerular disease is ambiguous. For example, primary MCD and FSGS are considered as a spectrum of diseases that are provoked by humoral permeability factors [47], while secondary cases indicate the presence of an identifiable etiology [48,49]. However, the identities of the permeability factors for MCD/FSGS are yet to be revealed [50]. For MN, the antibodies against potent etiological factors, such as the phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R) [51] and thrombospondin type-1 domain-containing 7A (THSD7A) [52], have been detected. Therefore, the classification based on the terminology of “primary” that indicates an unknown etiology may no longer make sense for patients with MN [53].

Second, this revision does not completely cover the recently reported disorders, such as tubulointerstitial nephritis with IgM-positive plasma cells [54]. Furthermore, in the near future, the newly developed technical approaches in kidney research including multi-omics analysis will probably reveal new pathogenesis for kidney diseases [55,56],therefore, it is necessary to continue the revision of the diagnosis panel with every new result.

Conclusion and future perspectives

The revised J-RBR/J-KDR 2018 system has attempted to cover the current classification and diagnosis of kidney diseases based on pathogenesis. It can provide data of higher quality on the demographics of kidney diseases and their classifications. In addition, the revised J-RBR/J-KDR 2018 system will be a platform for standardized registration of kidney diseases, and with this platform, we expect to promote international collaborations in research.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all their colleagues who participated in the J-RBR (Online Resource 2). This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Intractable Renal Diseases Research, Research on Rare and Intractable Diseases, and Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (H29-nanchi-ippan-017).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors have declared no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The J-RBR/J-KDR and its revision were approved from the ethical committee of the Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmaceutical Sciences (approval number: 233) and the Japanese Society of Nephrology [approval number: 62(3-6)]. All the participating institutions and hospitals individually approved this study. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. J-RBR/J-KDR is registered with the UMIN Clinical Trial Registry (UMIN000000618).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sugiyama H, Yokoyama H, Sato H, et al. Japan Renal Biopsy Registry: the first nationwide, web-based, and prospective registry system of renal biopsies in Japan. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2011;15(4):493–503. doi: 10.1007/s10157-011-0430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen AH, Nast CC, Adler SG, et al. Clinical utility of kidney biopsies in the diagnosis and management of renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 1989;9:309–315. doi: 10.1159/000167986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richards NT, Darby S, Howie AJ, et al. Knowledge of renal histology alters patient management in over 40% of cases. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 1994;23:1255–1259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo KT, Chan CM, Chin YM, et al. Global evolutionary trend of the prevalence of primary glomerulonephritis over the past three decades. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;116:337–346. doi: 10.1159/000319594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGrogan A, Franssen CFM, De Vries CS. The incidence of primary glomerulonephritis worldwide: a systematic review of the literature. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2011;26:414–430. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiorentino M, Bolignano D, Tesar V, et al. Renal biopsy in 2015—from epidemiology to evidence-based indications. Am J Nephrol. 2016;43:1–19. doi: 10.1159/000444026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Shaughnessy MM, Hogan SL, Thompson BD, et al. Glomerular disease frequencies by race, sex and region: results from the international kidney biopsy survey. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2018;33:661–669. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugiyama H, Yokoyama H, Sato H, et al. Japan Renal Biopsy Registry and Japan Kidney Disease Registry: committee report for 2009 and 2010. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:155–173. doi: 10.1007/s10157-012-0746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugiyama H, Shimizu A, Sato H. Annual report of J-RBR/J-KDR 2018 [in Japanese]. https://cdn.jsn.or.jp/news/180711_kp.pdf. Accessed 31 Dec 2019.

- 10.Yokoyama H, Taguchi T, Sugiyama H, et al. Membranous nephropathy in Japan: Analysis of the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR) Clin Exp Nephrol. 2012;16:557–563. doi: 10.1007/s10157-012-0593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yokoyama H, Narita I, Sugiyama H, et al. Drug-induced kidney disease: a study of the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry from 2007 to 2015. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2016;20:720–730. doi: 10.1007/s10157-015-1201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komatsu H, Fujimoto S, Yoshikawa N, et al. Clinical manifestations of Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis and IgA nephropathy: comparative analysis of data from the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR) Clin Exp Nephrol. 2016;20:552–560. doi: 10.1007/s10157-015-1177-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishi S, Muso E, Shimizu A, et al. A clinical evaluation of renal amyloidosis in the Japan renal biopsy registry: a cross-sectional study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2017;21:624–632. doi: 10.1007/s10157-016-1326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ichikawa K, Konta T, Sato H, et al. The clinical and pathological characteristics of nephropathies in connective tissue diseases in the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2017;21:1024–1029. doi: 10.1007/s10157-017-1398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiromura K, Ikeuchi H, Kayakabe K, et al. Clinical and histological features of lupus nephritis in Japan: a cross-sectional analysis of the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR) Nephrology (Carlton) 2017;22:885–891. doi: 10.1111/nep.12863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakagawa N, Hasebe N, Hattori M, et al. Clinical features and pathogenesis of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis: a nationwide analysis of the Japan renal biopsy registry from 2007 to 2015. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018;22:797–807. doi: 10.1007/s10157-017-1513-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okabayashi Y, Tsuboi N, Amano H, et al. Distribution of nephrologists and regional variation in the clinical severity of IgA nephropathy at biopsy diagnosis in Japan: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e024317. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katsuno T, Ito Y, Kagami S, et al. A nationwide cross-sectional analysis of thrombotic microangiopathy in the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR) Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10157-020-01896-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yonekura Y, Goto S, Sugiyama H, et al. The influences of larger physical constitutions including obesity on the amount of urine protein excretion in primary glomerulonephritis: research of the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19:359–370. doi: 10.1007/s10157-014-0993-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokoyama H, Sugiyama H, Narita I, et al. Outcomes of primary nephrotic syndrome in elderly Japanese: retrospective analysis of the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR) Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19:496–505. doi: 10.1007/s10157-014-1022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakashima H, Kawano M, Saeki T, et al. Estimation of the number of histological diagnosis for IgG4-related kidney disease referred to the data obtained from the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR) questionnaire and cases reported in the Japanese Society of Nephrology Meetings. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2017;21:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s10157-016-1260-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komatsu H, Fujimoto S, Maruyama S, et al. Distinct characteristics and outcomes in elderly-onset IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura) with nephritis: nationwide cohort study of data from the Japan Renal Biopsy Registry (J-RBR) PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0196955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamoto R, Imai E, Maruyama S, et al. Regional variations in immunosuppressive therapy in patients with primary nephrotic syndrome: the Japan nephrotic syndrome cohort study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018;22:1266–1280. doi: 10.1007/s10157-018-1579-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto R, Imai E, Maruyama S, et al. Incidence of remission and relapse of proteinuria, end-stage kidney disease, mortality, and major outcomes in primary nephrotic syndrome: the Japan Nephrotic Syndrome Cohort Study (JNSCS) Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10157-020-01864-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Churg J, Sobin LH. Renal disease: classification and atlas of glomerular diseases. Tokyo: Igakushoin; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Churg J, Bernstein J, Glassock RJ. Renal disease: classification and atlas of glomerular diseases. 2. Tokyo: Igakushoin; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sethi S, Haas M, Markowitz GS, et al. Mayo clinic/renal pathology society consensus report on pathologic classification, diagnosis, and reporting of GN. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:1278–1287. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015060612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arimura Y, Muso E, Fujimoto S, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis 2014. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2016;20:322–341. doi: 10.1007/s10157-015-1218-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishi S, Ubara Y, Utsunomiya Y, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for nephrotic syndrome 2014. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2016;20:342–370. doi: 10.1007/s10157-015-1216-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kellum JA, Lameire N, Aspelin P, et al. Kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–138. [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Kidney Foundation K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(suppl 1):S1–S266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cattran DC, Coppo R, Cook HT, et al. The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: rationale, clinicopathological correlations, and classification. Kidney Int. 2009;76:534–545. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts ISD, Cook HT, Troyanov S, et al. The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney Int. 2009;76:546–556. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trimarchi H, Barratt J, Cattran DC, et al. Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy 2016: an update from the IgA Nephropathy Classification Working Group. Kidney Int. 2017;91:1014–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawamura T, Joh K, Okonogi H, et al. A histologic classification of IgA nephropathy for predicting long-term prognosis: emphasis on end-stage renal disease. J Nephrol. 2013;26:350–357. doi: 10.5301/jn.5000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.D’Agati VD, Fogo AB, Bruijn JA, et al. Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a working proposal. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:368–382. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weening JJ, D’Agati VD, Schwartz MM, et al. The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:241–250. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000108969.21691.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Appel GB, et al. Shonlein-henoch purpura. In: Brenner BM, et al., editors. Brenner and Rector’s the kidney. 7. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004. pp. 1411–1415. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berden AE, Ferrario F, Hagen EC, et al. Histopathologic classification of ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1628–1636. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uemura O, Nagai T, Ishikura K, et al. Creatinine-based equation to estimate the glomerular filtration rate in Japanese children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2014;18:626–633. doi: 10.1007/s10157-013-0856-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR From serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:982–992. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyrier A, Niaudet P. Acute kidney injury complicating nephrotic syndrome of minimal change disease. Kidney Int. 2018;94:861–869. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Imai E, Yamagata K, Iseki K, et al. Kidney disease screening program in japan: history, outcome, and perspectives. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:1360–1366. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00980207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou XJ, Laszik Z, Nadasdy T, et al. Silva's diagnostic renal pathology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2017. Algorithmic approach to the interpretation of renal biopsy; pp. 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis—a new look at an old entity. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1119–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1108178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arts DGT, De Keizer NF, Scheffer GJ. Defining and improving data quality in medical registries: a literature review, case study, and generic framework. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2002;9:600–611. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maas RJ, Deegens JK, Wetzels JF. Permeability factors in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: historical perspectives and lessons for the future. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2014;29:2207–2216. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glassock RJ. Secondary minimal change disease. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2003;18(Suppl 6):vi52–i58. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Agati VD. The many masks of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 1994;46:1223–1241. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rovin BH, Caster DJ, Cattran DC, et al. Management and treatment of glomerular diseases (part 2): conclusions from a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2019;95:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beck LH, Jr, Bonegio RGB, Lambeau G, et al. M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tomas NM, Beck LH, Jr, Meyer-Schwesinger C, et al. Thrombospondin type-1 domain-containing 7A in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2277–2287. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Floege J, Barbour SJ, Cattran DC, et al. Management and treatment of glomerular diseases (part 1): conclusions from a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2019;95:268–280. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takahashi N, Saeki T, Komatsuda A, et al. Tubulointerstitial nephritis with IgM-positive plasma cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3688–3698. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016101074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mariani LH, Kretzler M. Pro: “The usefulness of biomarkers in glomerular diseases”. The problem: Moving from syndrome to mechanism—Individual patient variability in disease presentation, course and response to therapy. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2015;30:892–898. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mariani LH, Pendergraft WF, Kretzler M. Defining glomerular disease in mechanistic terms: implementing an integrative biology approach in nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:2054–2060. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13651215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.