Abstract

Muscle-specific adult stem cells (MuSCs) are required for skeletal muscle regeneration. To ensure efficient skeletal muscle regeneration after injury, MuSCs must undergo state transitions as they are activated from quiescence, give rise to a population of proliferating myoblasts, and continue either to terminal differentiation, to repair or replace damaged myofibers, or self-renewal to repopulate the quiescent population. Changes in MuSC/myoblast state are accompanied by dramatic shifts in their transcriptional profile. Previous reports in other adult stem cell systems have identified alterations in the most abundant internal mRNA modification, N6-methyladenosine (m6A), conferred by its active writer, METTL3, to regulate cell state transitions through alterations in the transcriptional profile of these cells. Our objective was to determine if m6A-modification deposition via METTL3 is a regulator of MuSC/myoblast state transitions in vitro and in vivo. Using liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry we identified that global m6A levels increase during the early stages of skeletal muscle regeneration, in vivo, and decline when C2C12 myoblasts transition from proliferation to differentiation, in vitro. Using m6A-specific RNA-sequencing (MeRIP-seq), a distinct profile of m6A-modification was identified, distinguishing proliferating from differentiating C2C12 myoblasts. RNAi studies show that reducing levels of METTL3, the active m6A methyltransferase, reduced global m6A levels and forced C2C12 myoblasts to prematurely differentiate. Reducing levels of METTL3 in primary mouse MuSCs prior to transplantation enhanced their engraftment capacity upon primary transplantation, however their capacity for serial transplantation was lost. In conclusion, METTL3 regulates m6A levels in MuSCs/myoblasts and controls the transition of MuSCs/myoblasts to different cell states. Furthermore, the first transcriptome wide map of m6A-modifications in proliferating and differentiating C2C12 myoblasts is provided and reveals a number of genes that may regulate MuSC/myoblast state transitions which had not been previously identified.

Subject terms: Muscle stem cells, Transcriptomics, Stem-cell differentiation

Introduction

Skeletal muscle regeneration is reliant upon a population of skeletal muscle-specific adult stem cells (MuSCs) and their ability to employ a myogenic program to form new skeletal muscle. In mature skeletal muscle, MuSCs remain in a quiescent state until activated by injury associated ques, at which point they enter the cell cycle, give rise to a transient myoblast population, and divide1,2. After a series of cell divisions, a subset of MuSCs will return to the quiescent state to renew the MuSC population that is able to respond to subsequent injuries while another subset of MuSCs will commit to the myogenic lineage and proceed to terminal differentiation3. MuSCs that differentiate, will restore damaged skeletal muscle through formation of new myofibers or fusion with existing myofibers. The process of MuSC differentiation and fusion is known to include the choreographed expression of several transcription factors termed the myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) including myoblast determination protein 1 (MyoD), myogenic factor 5 (Myf5), and myogenin (Myog)2. The temporal sequence of the expression of each MRF is well documented however, less is known about how modification of these mRNAs influences their translation and regulatory functions.

Posttranscriptional modifications, particularly the most abundant mRNA modification, N6-methyladenosine (m6A), have rapid, pronounced effects on mRNA stability, splicing, and translation, and therefore a cell’s transcriptional profile. m6A modification requires a defined set of “writer” proteins including the active methyltransferase, methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), to deposit methyl groups on mRNA4. Homozygous knockout of Mettl3 is embryonic lethal in mice5. Mettl3 knockout in embryonic stem cells, however, is viable and has been shown to increase cell proliferation and reduce differentiation capacity when cells are in the naive state6. Intriguingly, the opposite effects of Mettl3 knockout on cell state were observed in primed, pluripotent stem cells7. The effect of METTL3 depletion on stem cell state is also dependent on stem cell lineage. For example, reducing m6A levels in hematopoietic stem cells reduces proliferation and promotes differentiation8 whereas increasing m6A levels in adult neural stem cells reduces differentiation9. Therefore, m6A modifications are central in regulating stem cell state, however, their role is lineage dependent.

To date, only two studies have evaluated the effects of m6A modification on myoblasts10,11. The first study evaluated the effect of depletion of the m6A “eraser,” mRNA demethylase, Fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO), in the immortalized myoblast cell line, C2C12 myoblasts. Depletion of FTO led to impaired differentiation and fusion in vitro and impaired postnatal skeletal muscle development in vivo10. It is difficult to attribute these effects solely to reductions in m6A as FTO has recently been shown to act on m6A as well as N6,2-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am), a distinct mRNA modification which occurs exclusively near the mRNA cap12. The second study used siRNA to knockdown the m6A writer, METTL3, which would be expected to have inverse results from knockdown of the m6A eraser, FTO, however a reduction in MyoD mRNA levels and protein expression of the terminal differentiation marker embryonic myosin heavy chain (eMHC) was observed11. Consequently, m6A modification appears to be implicated in C2C12 myoblast state transitions, but the directionality of the effect cannot be inferred from the available literature.

Our objective was to determine if m6A deposition on mRNA via Mettl3 is a regulator of MuSC/myoblast state in vitro and in vivo. This study defines the temporal dynamics of m6A levels in whole skeletal muscle tissue during the regeneration process, post injury, and in C2C12 myoblasts during in vitro proliferation and differentiation. Using liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC–MS), we identified increased m6A levels in skeletal muscle tissue in the early stages of tissue regeneration compared to pre-injury. Furthermore, LC–MS analysis and m6A-specific RNA-sequencing (MeRIP-seq) demonstrated increased m6A in C2C12 myoblasts during proliferation compared to differentiation. MeRIP-seq of proliferating and differentiating C2C12 myoblasts reveals the first comprehensive profile of mRNAs that are preferentially m6A-modified in different myoblast states and reveals that m6A modification is closely linked to genes implicated in transcriptional regulation during proliferation. Finally, we show that Mettl3 knockdown slows proliferation in primary mouse MuSCs and enhances their primary transplant capacity.

Results

Global m6A levels decline during the MuSC transition from proliferation to differentiation

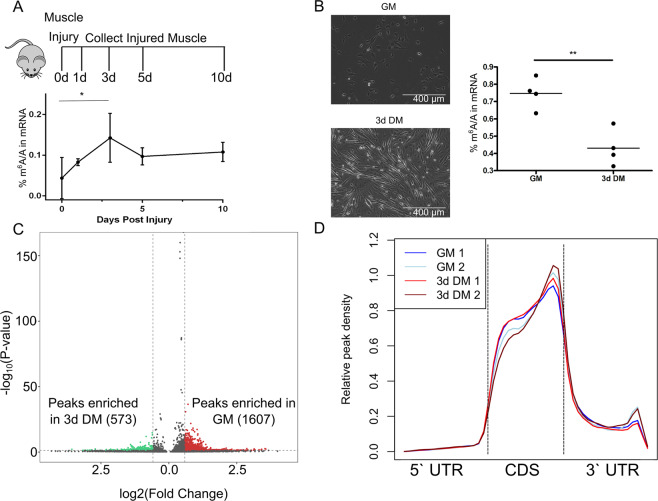

Global m6A levels were assessed in skeletal muscle tissue after BaCl2 induced injury using LC–MS. In whole skeletal muscle tissue, relative m6A levels increased at 3 days post injury (dpi) compared to baseline (Fig. 1a). 3 dpi corresponds to a time of substantial MuSC proliferation but also infiltration of a number of other cell types that support the skeletal muscle regenerative process13–15. Global m6A levels at later times points when MuSC differentiation is initiated (i.e., 5 and 10 dpi) were not different from baseline suggesting this increase in m6A levels was specific to MuSC proliferation. To understand the dynamics of global m6A levels at the MuSC/myoblast level, during this period of rapid proliferation, C2C12 myoblasts (Fig. 1b) and primary mouse myoblasts (Supplementary Fig. 1A) were used. m6A levels were greater when cells were cultured in proliferation favoring media for 24 h (GM) compared to when cells were switched from GM to serum restricted, differentiation inducing media for 3 days (3d DM) in both myoblast models. Because both myoblast models behaved similarly and due to the large amount of input required for downstream applications, C2C12 cells were used for subsequent cell culture experiments, unless otherwise specified.

Fig. 1. m6A-modifications are dynamically regulated in regenerating skeletal muscle and C2C12 myoblasts.

a The TA of Pax7nTnG mice (n = 3–4 per time point) were injected with BaCl2, and global m6A levels were measured by LC–MS at 0, 1, 3, 5, and 10 dpi. *P < 0.05. b mRNA was isolated from C2C12 myoblasts during proliferation (GM) or 3 days after differentiation was induced (3d DM) and global m6A levels were measured by LC–MS (n = 4). **P < 0.01. c Volcano plot displaying unique m6A-peaks significantly enriched in C2C12 myoblasts in GM (red, n = 2) or 3d DM (green, n = 2) according to MeRIP-seq. d Distribution of m6A peaks along all transcripts identified as m6A-modified by MeRIP-seq. Each individual replicate is plotted (GM, n = 2; 3d DM, n = 2). UTR untranslated region, CDS protein coding region.

MeRIP-sequencing reveals dynamic changes in transcript-specific m6A-modification abundance but not the frequency of m6A-modification location on transcripts

To map the changes in the transcriptome marked by m6A as myoblasts transition from proliferation to differentiation, MeRIP-seq was performed in GM and 3d DM samples. Confirming our LC–MS data, MeRIP-seq revealed an enrichment of m6A-modified transcripts in GM (vs. 3d DM) samples (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Tables 1, 2). The distribution of m6A across transcripts was similar in GM and 3d DM samples with modifications being most abundant at the boundary of the coding sequence and 3′ regions (Fig. 1d). Therefore, we concluded that a global- and transcript-specific program of m6A enrichment is associated with maintaining myoblasts in a proliferative state and that this effect is not driven by differences in the location of m6A-modification on transcripts.

Characterization of the proliferation-specific m6A profile at the individual transcript level

MeRIP-seq analysis revealed 1607 m6A peaks representing 862 unique genes enriched in GM compared to 3d DM (Fig. 1c). The top m6A-enriched transcripts, based on fold change (GM to 3d DM), were Dmp1, Ccdc73, GM5141, Zfp316, Zfp157, Cebpa, Gprin1, Chst7, Ncam1, and Nlrx1 (Supplementary Table 1). Comparing the MeRIP-seq analysis with results from concurrently performed bulk RNA-seq (Supplementary Table 3) it was noted that only 14 transcripts were both m6A-enriched in GM compared to 3d DM (Supplementary Table 4) and differentially expressed in GM (vs. 3d DM). Of the 14 common transcripts, 7 were zinc finger proteins. To evaluate the effect of m6A-modification on individual gene expression, we compared whether having at least one m6A-modification predicted relative gene expression (Fig. 2a). Overall, transcripts with at least one enriched m6A-modification site in myoblasts during proliferation (i.e., GM samples) were moderately more likely to have increased gene expression; increased expression was determined by fold change >1.0 (GM/3d DM) for transcripts in the RNA-seq dataset (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. MeRIP-seq analysis identifies transcriptional regulation as the main target of m6A-modification during C2C12 myoblast proliferation.

a The abundance of m6A-modified vs. non-m6A-modified mRNAs in GM based on RNA-seq comparing GM vs. 3d DM samples. m6A-modification was determined by MeRIP-seq. Inset, box plot of the mRNA log fold change (GM/3d DM) of m6A-modified and non-m6A-modified mRNAs. ****P < 2.2 × 10−16 (two-sided Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). b Enriched PANTHER GO-slim Molecular Function Pathways identified from m6A-enriched genes in GM vs. 3d DM samples. c Venn diagram displaying overlap of GO-slim Molecular Function Pathways overrepresented in GM vs. 3d DM samples in both RNA-seq (blue) and MeRIP-seq (red) datasets.

To identify Molecular Function Pathways associated with the m6A-modified mRNAs that were overrepresented in GM, we performed PANTHER GO-slim Molecular Function analysis (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table 5)16. An emerging theme from the PANTHER analysis was that m6A-modified transcripts that clustered into related Molecular Function Pathways were related to transcriptional regulation (e.g., transcription factor binding, transcription coregulator activity, and chromatin binding). We next performed PANTHER GO-slim analysis on differentially regulated transcripts during GM compared to 3d DM, based on bulk RNA-seq results (Supplementary Table 6); we identified nine overlapping Molecular Function Pathways between the RNA-seq and MeRIP-seq analyses (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 7). Similar to our analysis at the single transcript level, the incomplete overlap of affected Molecular Function Pathways between the MeRIP-seq and RNA-seq datasets indicates that some of the functional outcomes of m6A-modifications during GM are beyond enhanced transcript stabilization and/or decay.

Characterization of the differentiation-specific m6A profile at the individual transcript level

We repeated the analysis for transcripts that emerged as m6A-enriched in the 3d DM MeRIP-seq dataset; 573 m6A peaks were identified as associated with 340 unique genes that were significantly enriched in 3d DM vs. GM samples (Fig. 1c). Using fold change, the top 10 m6A-enriched transcripts in 3d DM were Flcn, Zfp712, Zfp59, Zfp964, Atxn712, Gsdme, Taf12, Col23a1, Ankfy1, and Cep851 (Supplementary Table 2). Only six transcripts were both differently regulated in the RNA-seq dataset and m6A-enriched in 3d DM based on the MeRIP-seq dataset (Supplementary Table 8). Similar to GM, in 3d DM having at least one m6A-modification enrichment site present on transcript tended to increase the likelihood that the corresponding transcript was expressed to a greater degree in 3d DM vs. GM (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3. MeRIP-seq analysis identifies microtubule binding as a main target of m6A-modification during C2C12 myoblast differentiation.

a The abundance of m6A-modified vs. non-m6A-modified mRNAs in 3d DM based on RNA-seq comparing 3d DM vs. GM samples. m6A modification was determined by MeRIP-seq. Inset, box plot of the mRNA log fold change (3d DM/GM) of m6A-modified and non-m6A-modified mRNAs. ****P < 2.2 × 10−16 (two-sided Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). b Enriched PANTHER GO-slim Molecular Function Pathways identified from m6A-enriched genes in 3d DM vs. GM samples. c Venn diagram displaying overlap of GO-slim Molecular Function Pathways overrepresented in 3d DM vs. GM samples in both RNA-seq (blue) and MeRIP-seq (red) datasets.

PANTHER GO-slim Molecular Function Pathway analysis revealed fewer Molecular Function Pathways related to transcriptional regulation than appeared in the GM dataset (Figs. 2b, 3b). The most prominent pathway enriched in 3d DM was microtubule binding (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 8). Furthermore, unlike in GM, all Molecular Function Pathways identified in the MeRIP-seq dataset emerged as enriched in the RNA-seq dataset suggesting a closer link to m6A-modification and transcript abundance in 3d DM than in GM (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Tables 5, 9, 10).

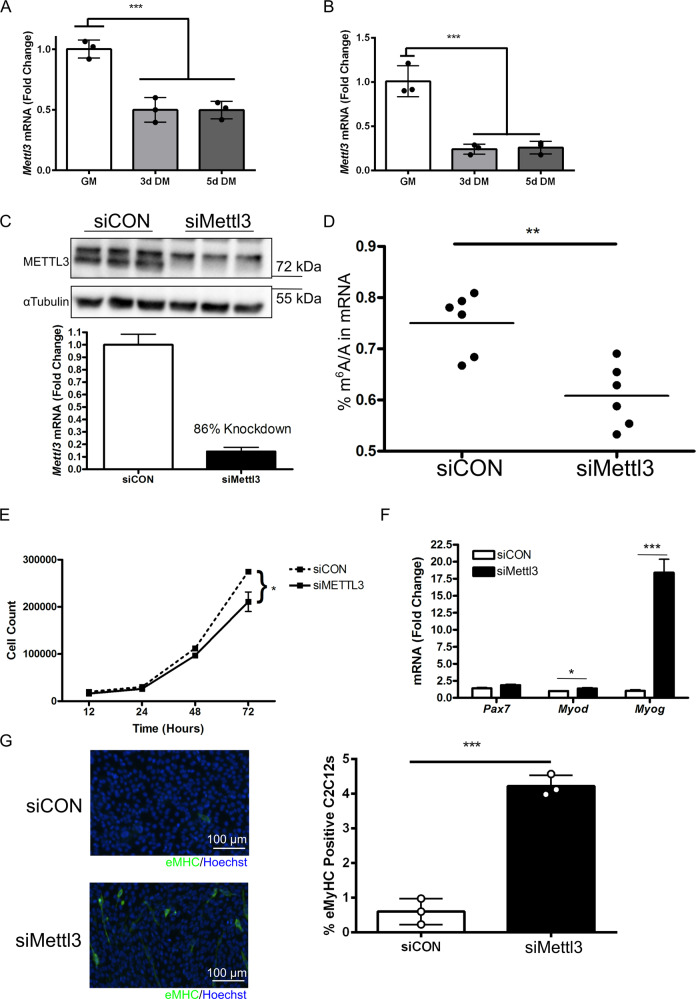

Mettl3 regulates the myoblast transition from proliferation to differentiation

We hypothesized that m6A levels were enriched in GM samples due to increased expression of the active m6A writer Mettl3. To model MuSC activity during regeneration, C2C12 myoblast and primary mouse myoblasts were cultured then prompted to differentiate in vitro by serum restriction; Mettl3 expression levels markedly declined in both C2C12 myoblast (Fig. 4a) and primary mouse myoblasts (Fig. 4b) after differentiation initiation.

Fig. 4. Mettl3 knockdown forces premature myoblast differentiation.

a Mettl3 gene expression levels were assessed via qPCR in C2C12 myoblasts in GM as well 3d and 5d DM (n = 3). ***P < 0.001. b Gene expression levels of Mettl3 were measured via qPCR in GM as well 3d and 5d DM in primary mouse myoblasts (n = 3). ***P < 0.001. c siRNA targeting Mettl3 was applied to C2C12 myoblasts for 2 days in proliferation favoring media and protein levels (immunoblotting) and gene expression (qPCR) levels of Mettl3 demonstrated an efficient knockdown (n = 3). d mRNA was isolated from C2C12 myoblasts after 2 days of siMettl3 or siCON and global m6A-modification levels were determined via by LC–MS (n = 6). **P < 0.01. e Total C2C12 myoblast number was counted at the time points indicated after treatment with siMettl3 or siCON (n = 3). *P < 0.05. f Gene expression levels of Pax7, Myod1, and Myog were measured via qPCR after 2 days of siMettl3 or siCON (n = 3). *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001. g Immunocytochemistry for eMHC in C2C12 cells (left) and quantification (right) after 2 days of siMettl3 or siCON (n = 3). ***P < 0.001.

To determine if prevention of m6A-modification deposition alone was adequate to initiate differentiation, C2C12 myoblasts were treated with siRNA targeting Mettl3 (Fig. 4c), which was successful in reducing the frequency of m6A-modification (Fig. 4d). Knockdown of Mettl3 reduced cell count (Fig. 4e). We next evaluated the effect of Mettl3 knockdown on MRFs associated with proliferation (Pax7), early differentiation (Myod1), and late differentiation (Myog). Gene expression of Myod1 and Myog were significantly increased after Mettl3 knockdown (Fig. 4f). Finally, Mettl3 knockdown significantly increased the number of C2C12 myoblasts expressing eMHC, a marker of terminal differentiation (Fig. 4g), indicating a transition from proliferation to differentiation despite cells being cultured in proliferation favoring media. Altogether these data support a model whereby Mettl3 knockdown in proliferating C2C12 myoblasts reduces global levels of m6A-modification and causes premature differentiation of myoblasts.

Mettl3 knockdown affects primary MuSC engraftment

To test the effect of Mettl3 knockdown on primary mouse MuSCs, MuSCs were isolated from CMV-luc mice, treated with one of four different short-hairpin constructs targeting Mettl3 (shMettl3) or a nonmammalian control (shCON, Fig. 5a); the two most effective constructs at reducing Mettl3 levels were used for transplantation experiments. Knockdown of Mettl3 in primary mouse MuSCs effectively reduced luciferase expression (a surrogate for nuclei number, Fig. 5b) and percent confluence (Supplementary Fig. 2A) after 7 days of culture in a proliferation favoring media. When Mettl3 was knocked down prior to transplantation the likelihood for engraftment and bioluminescent expression of engrafted MuSCs improved (Fig. 5c, d). Additionally, we performed serial transplants to identify if MuSCs maintained engraftment potential; however, none of the shMettl3 or shCON transplants were capable of engraftment upon secondary transplantation, indicating no MuSCs were retained in a stem like state after primary transplantation (data not shown).

Fig. 5. Mettl3 knockdown enhances MuSC engraftment after primary transplantation.

a Primary mouse MuSCs were isolated from CMV-luc mice, treated with shRNAs targeting Mettl3 or a nonmammalian control sequence, and cultured for 7 days prior to measuring Mettl3 gene expression levels via qPCR (n = 4). ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. b Luminescence was measured in primary mouse MuSCs after 7 days of culture and treatment with shMettl3 or shCON (n = 4). *P < 0.05. c Schematic of primary mouse MuSC transplantation strategy; Primary mouse MuSCs were isolated from CMV-luc mice and transplanted into the TA of NSG knockout mice (n = 8 transplants per condition) and followed for 40 days. d Bioluminescence was measured at the time points indicated (left) and representative images are shown with the number of transplants with successful engraftment indicated (right). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (main effect of shRNA, one-way ANOVA).

Discussion

In the experiments described here, we provide the first evidence that global m6A levels increase after skeletal muscle injury at a time point corresponding with rapid MuSC proliferation. Additionally, the use of LC–MS m6A measurement and MeRIP-seq build upon an earlier report that showed, using the RNA dot blot method, global m6A levels in primary mouse myoblasts or C2C12 myoblasts are increased during proliferation and decline during differentiation in vitro10. Our MeRIP-seq analysis extended previous findings showing that not only are global m6A levels greater in proliferation, but that there are also unique subsets of transcripts which are preferentially methylated in different cell states (i.e., proliferation and differentiation).

The transition from myoblast proliferation to differentiation is accompanied by drastic alterations in the transcriptome17–19. Transcriptional changes influencing MuSC/myoblast state transitions have been shown to be affected by a number of processes including changes in DNA and histone methylation of the MRFs20. This study provides the first, comprehensive identification of transcripts that are m6A-modified in myoblasts during proliferation and in early differentiation. We found no differences in methylation of transcription factors known to drive MuSC state changes such as Pax7, Myod1, or Myog suggesting that the MRFs are not direct targets of dynamic m6A-modification but rather, changes in their expression resulting in altered cell state is a secondary effect. Intriguingly, of the top m6A-enriched transcripts in GM and in 3d DM, many have not been previously linked to MuSC/myoblast function but have been demonstrated to regulate transcription and even cell state in other cell types. For example, a number of zinc finger proteins including Zfp316 and Zfp157 (in GM) as well as Zfp712, Zfp59, and Zfp964 (in 3d DM) were among the top ten transcripts differentially m6A-enriched during proliferation and differentiation, respectively. While many of the zinc finger proteins that emerged from the MeRIP-seq dataset have not been previously implicated in MuSC/myoblast state transitions, the regulation of myogenic differentiation by other zinc finger proteins is well established21. Notably, Zfp637 was identified as an m6A-enriched transcript in GM, compared to 3d DM. Zfp637 repression is reported to suppress C2C12 myoblast proliferation and its over expression prevents C2C12 myoblast differentiation22. Furthermore, the PANTHER GO-slim Molecular Function analysis revealed that 11/17 of the Molecular Function pathways that were overrepresented by m6A-enriched transcripts in GM (vs. 3d DM) were related to transcriptional regulation. Therefore, it appears likely that during proliferation, m6A-modification is used, in part, to affect the abundance of transcription regulating proteins, such as zinc finger proteins, which in turn define a transcriptional profile favoring cell cycle progression.

A dynamic pattern of Mettl3 expression during myoblast state changes was observed however, the upstream regulation of this expression remains elusive. m6A has been shown to be responsive to a number of external cues such as heat shock23 or inflammatory challenges24 at the cellular level or restraint stress at the organismal level25. During skeletal muscle injury a number of changes to the MuSC microenvironment occur, including cytokine release from invading immune cell populations26,27 and release of growth factors from the extracellular matrix28. It is likely that one or a combination of these factors is able to repress Mettl3 expression and drive the reduction in m6A levels observed, thereby facilitating the transition from proliferation to differentiation in MuSCs at the correct time.

Transplantation of Mettl3-knockdown MuSCs showed improved engraftment capacity compared to controls. Engraftment potential determined by bioluminescence imaging has been identified to be an approximate representation of maintenance of MuSC self-renewal, and therefore stem potential29, but is also influenced by the MuSCs’ niche colonization capability30. Culturing of MuSCs in vitro prior to transplantation, as was done in this study, is documented to prompt the transition from a stem to a progenitor like state and impair engraftment potential after transplantation29,31,32. We hypothesize that this enhanced engraftment capacity of Mettl3-knockdown MuSCs is due to increased resistance to activation, and delayed progression toward a progenitor like state, prior to transplantation, resulting in enhanced niche colonization capability. The failure of secondary transplants, from any condition, to engraft supports a loss of stem potential and underscores that the increase in bioluminescent signal observed in Mettl3-knockdown MuSCs was likely due to enhanced niche colonization and not maintenance of a stem like state. A delay to activation of MuSCs due to Mettl3 knockdown supports a framework where the function of m6A-modification in MuSCs is to regulate transitions between cell states including quiescence to activation as well as proliferation to differentiation.

In conclusion, we elucidate METTL3-mediated m6A regulation as an important regulator of MuSC/myoblast state transitions and provide the first comprehensive map of m6A-modified transcripts during myoblast proliferation and differentiation. Future investigation into the biological function of the genes from the datasets developed here may glean new insight into the earliest stages of terminal differentiation commitment in MuSC/myoblasts. Furthermore, an understanding of the upstream signal that leads to the decline in Mettl3 transcription upon differentiation initiation would be invaluable in understanding how MuSC-microenvironment communication underlies transcriptional changes that regulate the initial steps in myogenic differentiation.

Materials and methods

Mice and animal care

All mice were maintained according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and all procedures were approved by The Cornell University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. For skeletal muscle injury experiments, previously published B6.Cg-Pax7tm1(Cre/ERT2)Gaka/J mice33 (JAX: 017763) were crossed with B6N.129S6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(CAG-tdTomato*,−EGFP)/Ees/J mice34 (JAX: 005304) to produce the following mouse: Pax7CreERT2;Rosa26nTnG (hereafter referred to as Pax7nTnG). Pax7nTnG mice were used for all muscle injury experiments. Mice ubiquitously expressing luciferase, FVB-TG(CAG-luc,-GFP)L2G85Chco/J (JAX: 008450, CMV-luc mice)35,36, were used for the isolation of donor cells for transplantation experiments and were transplanted into immunodeficient NSG mice (NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ, JAX: 005557)37,38. Animals were randomly assigned to treatment groups and the treatment group of samples derived from each animal were blinded to the investigator performing downstream analyses. The number of animals per experimental condition are reported in the figure legends and sample sizes were based on convention in the field.

Skeletal muscle injury

To induce skeletal muscle injury, 50 µL of 1.2% BaCl2 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was injected into the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle of Pax7nTnG mice under isoflurane anesthesia. Mice were sacrificed at 0 (baseline), 1, 3, 5, and 10 dpi and the TA muscle was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until mRNA isolation.

C2C12 myoblast culture

C2C12 myoblasts (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in a growth medium containing high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco, Gaithers MD, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 4 mM Glutamax (Gibco, Gaithers MD, USA), and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Corning, Pittston, PA, USA). Cultures were not tested for mycoplasma contamination. When cultures were between 80-100% confluent they were switched to a media containing high glucose DMEM supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated horse serum to promote differentiation. GM samples were taken after 24 h of culture in growth medium when cultures were ~50% confluent and DM samples were taken at various days after the switch to differentiation media, as indicated. All C2C12 myoblasts were used between passage 5 and 10 and were cultured in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C on collagen (Type I, Rat Tail, Corning, Pittston, PA, USA) coated plates. As per convention in the field, all experiments were repeated at least three times for all cell culture experiments (excluding MeRIP-seq experiments) with specific values noted in the figure legends.

Primary mouse myoblast culture

Passage 17–20 primary mouse myoblasts, obtained as previously described, were used39. Primary mouse myoblasts were cultured in a growth medium of 43% low glucose DMEM (Gibco, Gaithers MD, USA), 40% Ham’s F10 (Gibco, Gaithers MD, USA), 15% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, 1% Glutamax, and 2.5 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). When cultures were between 80 and 100% confluent, they were switched to a media containing 2% heat-inactivated horse serum. Similar to C2C12 myoblast experiments, GM samples were obtained at ~50% confluency (24 h after seeding) and DM samples at various days after the switch to differentiation media. Primary mouse myoblasts were seeded on collagen (Type I, Rat Tail) coated plates and maintained in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C.

m6A LC–MS

For analysis of m6A levels in skeletal muscle tissue, RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For analysis of m6A levels in cell lysates and RNA isolated from skeletal muscle tissue mRNA was isolated via Dynabeads Oligo(dT)25 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as recommended by the manufacturer. The sample preparation and LC–MS method protocol was adapted from a previously published protocol40. One hundred nanograms of mRNA was incubated with 2 U nuclease P1 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a buffer of DEPC treated 25 mM NaCl and 2.5 mM ZnCl2 at 37 °C for 60 min to isolate individual nucleotides followed by incubation for 60 min at 37 °C with 0.5 U alkaline phosphatase (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) to remove all phosphate groups, thus producing nucleosides. Samples were then diluted to 200 µL with Di H2O. Adenosine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and m6A (Toronto Research Chemicals, North York, Canada) standard curves were also prepared by serial dilution in Di H2O. Prior to injection into the LC/MS/MS system equipped with Accela autosampler and pump (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and TSQ Quantum Access (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), samples and calibration points were mixed with an equal volume solution containing 10 µM of 13C5-Uridine (Toronto Research Chemicals, North York, Canada) in 0.1% formic acid in Di H2O as an internal standard. Ten microliters of sample was injected into a Phenomenex Luna C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). An elution gradient of 0.1% formic acid in Di H2O and 0.1% formic acid in methanol at 0.45 mL/min was run as follows: 0 min, 10% methanol; 5 min, 99% methanol; 7 min, 99% methanol; 8 min, 10% methanol; 12 min, 10% methanol. XCalibur (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) software was used for quantification of m6A and adenosine. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions in positive mode were: m/z 282–150 for m6A and m/z 268–136 for adenosine. The m6A to total adenosine (m6A + total adenosine) peak area ratio was calculated and differences in ratios reported.

MeRIP-sequencing

RNA for MeRIP-seq was isolated from C2C12 myoblasts using the Omega E.Z.N.A.® Total RNA Kit I (Omega Bio-Tek Inc, Norcross, GA, USA). RNA quality was determined by denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis. mRNA was isolated from >120 µg total RNA using Arraystar Seq-StarTM poly(A) mRNA Isolation Kit (ArrayStar Inc, Rockville, MD, USA) as per the manufacturer’s directions. Isolated mRNA was fragmented to a median size of 10 nt in 20 µL of a buffer containing 10 mM Zn2+ and 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) for 7 min at 94 °C. Fragment size was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Ten percent of fragmented mRNA was saved for RNA-sequencing to serve as input control for MeRIP-seq. The remaining fragmented mRNA was used for m6A immunoprecipitation.

m6A immunoprecipitation was performed by combining fragmented mRNA with 2 µg anti-m6A antibody (Cat: 202 003, Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany) and rotated head over tail for 120 min at 4 °C in 500 µL total volume. Twenty microliters of DynabeadsTM M-280 sheep anti-rabbit IgG (clone 11204D, Thermo Fisher Scientific Waltham, MA, USA) were blocked with 0.5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin at 4 °C for 120 min. The blocked Dynabeads and fragmented mRNA/antibody mixture were combined for 120 min at 4 °C. The solution was then washed 3× with a buffer of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% NP-40 followed by 2× washes with a buffer comprised of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM NaCl, and 0.1% NP-40. mRNA immunoprecipitated to the DynabeadsTM was separated by incubation with 200 µL of an elution buffer [10 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.4) 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% SDS, 40 U proteinase K (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany)] for 30 min at 50 °C. mRNA was then extracted by phenol–chloroform and ethanol precipitated before sequencing.

The KAPA Stranded mRNA-seq Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to prepare the RNA-seq libraries for m6A immunoprecipitated mRNA and input control mRNA libraries. Quality of the libraries was determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. The HiSeq 3000/4000 PE Cluster Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to generate clusters from the prepared libraries following the manufacturer’s instructions. The clustered libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 system.

MeRIP-sequencing analysis

The 5′, 3′-adaptor trimmed reads were aligned to the mm10 reference genome using HISAT2 (v2.1.0)41. ExomePeak was used for MeRIP peak calling and statistically significant MeRIP enriched regions (MeRIP peaks) were identified at the sample level with a significance threshold of P ≤ 0.0542. ExomePeak was also used to compare transcripts which were differentially m6A-modified between the GM and 3d DM samples with significance set at P ≤ 0.0542.

RNA-sequencing analysis

The input control RNA-sequencing results were subjected to differential gene expression analysis using edgeR43 in RStudio (Version 3.6.1). Genes with at least two counts per million in at least three of the samples were kept for analysis.

Pathway analysis

Pathway analysis was conducted using the PANTHER (version 14.1) GO-Slim Molecular Function Overrepresentation Test with a false discovery rate (FDR) correction16. PANTHER analysis was performed using lists of m6A-modified transcripts that were enriched (P < 0.05) in GM and separately on lists of transcripts that were enriched in 3d DM based on the MeRIP-seq dataset. PANTHER analysis was also performed using the list of transcripts that were differentially regulated between GM and 3d DM according to the RNA-seq data (FDR < 0.05, log fold change >1.5 or <−1.5).

C2C12 myoblast siRNA transfection

C2C12 myoblasts were reverse transfected with siRNA-lipid complexes (RNAiMAX, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) targeting Mettl3 (siMettl3, Cat: 4457298, Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) or a non-targeting control (siCON, Cat: 4390846, Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). C2C12 myoblasts were maintained in growth medium for 48 h after transfection prior to analysis of gene expression, protein expression, and global m6A levels.

Quantitative RT-PCR

The Applied Biosystems High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used to synthesize cDNA via reverse transcription of 2 µg RNA extracted using Omega E.Z.N.A.® Total RNA Kit I (Omega Bio-Tek Inc, Norcross, GA, USA) as per the manufacturer’s directions. RNA quality and quantity were determined spectrophotometrically. Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) was used to measure mRNA levels of Mettl3 (Mm01316319), Pax7 (Mm0135484), Myod1 (Mm00440387), and Myog (Mm00446195). Expression levels were normalized to 18S (Mm03928990) expression using the Taqman Gene Expression System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Immunoblotting

Cell lysates were collected using RIPA buffer containing protease (cOmplete, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and phosphatase (PhosSTOP, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) inhibitors. Following cell lysis, the protein fraction was cleared of other cellular debris via centrifugation (12,000 × g, 15 min, 4 °C). Ten micrograms of protein, as determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific Waltham, MA, USA), was loaded on 10% SDS gels and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with a chemiluminescent blocking buffer (bl∅kTM—CH, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) for 60 min at room temperature (RT) before being transferred into a solution containing either a METTL3 primary antibody (1:1000 dilution in chemiluminescent blocking buffer, overnight incubation at 4 °C, Cat: 15073-1-AP, Proteintech Group Inc, Rosemont, IL, USA) or an HRP-conjugated ɑ-TUBULIN primary antibody (1:1000 dilution in chemiluminescent blocking buffer, 60 min incubation at RT, Cat: 9099, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA). Membranes incubated with the METTL3 antibody were then washed 3 × 5 min in 0.1% Tween in tris-buffered saline following a 60 min incubation in goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:100,000 dilution in chemiluminescent blocking buffer, Cat: SA00001-2, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA,). Membranes were then incubated in SuperSignalTM West Femto (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 1 min and visualized on the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP. METTL3 protein was normalized to α-TUBULIN expression using the ImageLab 4.1 software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

C2C12 myoblast population expansion assay

To determine the effect of Mettl3 knockdown of cell number, C2C12 myoblasts that were cultured in 6-well cell culture dishes were counted using the Moxi Z Mini Automated Cell Counter (ORFLO Technologies, Ketchum, ID, USA) 12, 24, 48, and 72 h after seeding and siRNA transfection in growth medium.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was used to determine expression of eMHC. C2C12 myoblasts were fixed for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde at RT before 3 × 5 min washes in PBS. Fixed, C2C12 myoblasts were blocked for 60 min at RT in 5% goat serum then incubated with primary eMHC antibody supernatant (DSHB Hybridoma Product F1.652, F1.652 was deposited to the DSHB by Blau, Helen M.)44 overnight at 4 °C. C2C12 myoblasts were then washed 3 × 5 min in PBS and incubated in secondary antibody (Alex Fluor® 488 goat anti-mouse, Cat: A11029, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) diluted 1:1000 in 1% goat serum. Hoechst 33342 was used as a counterstain to identify nuclei and stained cells were imaged on the Celigo S Imaging Cytometer (Nexcelom Bioscience, Lawrence, MA, USA).

Primary mouse MuSC isolation

Primary mouse MuSC isolation was performed as previously described31. CMV-luc mice were anesthetized with isoflurane followed by cervical dislocation prior to harvesting of all hindlimb muscles. Muscles were incubated in a digestion cocktail of low glucose DMEM and 2.5 mg/mL Collagenase D (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 15 min at 37 °C. Physical dissociation was then performed using the GentleMACS system (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), followed by the addition of Dispase II (0.04 U/mL final concentration stock, Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and an additional 40 min incubation at 37 °C. Further physical dissociation of the muscle tissue was performed using an 18-gauge needle. Cell suspensions were passed through a prewashed 100 µM filter, then a 40 µM filter to remove debris. The remaining cells were pelleted via centrifugation (700 × g, 7 min, 4 °C) and resuspended in red blood cell lysis buffer (IBI Scientific, Dubuque, Iowa, USA) for 5 min at RT. The cell suspension was pelleted again, resuspended in 1 mL of a cocktail of biotin conjugated primary antibodies specific for CD45 (2 µL, clone 30-F11, Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), CD31 (5 µL, clone 390, Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), CD11b (5 µL, clone M1/70, Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), and Sca1 (5 µL, clone D7, Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), and incubated, on ice, for 25 min. Streptavidin microbeads (12 µL, Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) were added to the cell suspension/antibody cocktail mixture and incubated, on ice, for 10 min. After incubation the mixture was passed through prewashed magnetic columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Cells were pelleted and resuspended in a 1 mL solution containing antibodies specific for the following proteins: CD34 (eFluor450, clone ram34, Invitrogen eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) α7-integrin (AlexaFluor647, clone r2f, Ablab, British Columbia, Canada), and streptavidin (PE-Cy7, Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA). After a 20 min incubation on ice, the cell suspension was washed, pelleted, and resuspended in a 200 µL 1:100 solution of propidium iodide. CD34+/α7-integrin+/CD45−/CD31−/CD11b−/Sca1− cells were isolated via flow cytometry. Isolated primary mouse MuSCs were then seeded on plates coated with laminin (20 µg/mL, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and RetroNectin® Recombinant Human Fibronectin Fragment (15 µg/mL, Takara Bio USA, Mountainview, CA, USA) in the same growth medium used for primary mouse myoblast culture.

Primary mouse MuSC shRNA transfection

For in vitro experiments primary MuSCs from CMV-luc mice were transfected with short-hairpin lentiviruses targeting Mettl3 (sh1, clone TRCN0000039110; sh2, clone TRCN0000039111; sh3, clone TRCN0000039112; sh4, clone TRCN0000039113, MISSION, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) or a nonmammalian targeting control (shCON, Cat: SHC002, MISSION, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) 12 h after seeding. Fresh growth medium was replaced 48 h after transfection and continued to be changed every 48 h for 7 days.

For transplantation experiments primary MuSCs from CMV-luc mice were transfected with shCON, sh2, sh3, or a combination of sh2 and sh3 (sh2/3) 12 h after seeding. Twenty-four hours following transfection MuSCs were harvested for transplantation.

Primary mouse MuSC transplantation

For primary transplantation experiments primary MuSCs isolated from CMV-luc mice from each shRNA condition (shCON, sh2, sh3, and sh2/3) were individually resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 175 MuSCs per 20 µL PBS 24 h after transfection in culture. NSG knockout mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and 20 µL of the MuSC cell suspension was injected into their TA muscles. Each TA muscle received MuSCs from one shRNA condition (i.e., shCON, sh2, sh3, and sh2/3) in a random fashion for a total of 8 replicates per condition across 16 recipient mice.

For secondary transplantation, the TA muscles of primary transplant recipient mice were harvested and digested as described in the primary mouse MuSC isolation section. The cell suspension resulting from each TA muscle was evenly divided and injected into two recipient TA muscles for a total of 8 replicates per condition across 16 recipient mice.

In vitro luciferase assay

To determine the effect of shRNA conditions on MuSC proliferation after 7 days in culture, primary MuSCs from CMV-luc mice were incubated in fresh growth medium containing 0.15 mg/mL D-Luciferin (Gold Biotechnology, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 15 min at 37 °C prior to measurement on a SpectraMax M3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA).

In vivo bioluminescent imaging

In vivo bioluminescent imaging was used to track MuSC behavior after transplantation. Transplant recipient mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and injected with 125 µL of 30 mg/mL D-Luciferin prior to imaging (Gold Biotechnology, St. Louis, MO, USA). Bioluminescent imaging was performed using the IVIS® Spectrum in vivo imaging system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Digital images were obtained 12 min after injections and analyzed using Living Image Software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, US). The engraftment threshold was set at 50,000 photons per second. Bioluminescent images were taken at 3, 11, 17, 25, 31, and 40 days after primary transplantation. For secondary transplantation experiments, bioluminescent images were taken 35 days after transplantation.

Confluence analysis

Confluence measurements were performed as previously described45. Briefly, confluence was determined as the area of the cell culture surface covered by cells as measured by the Celigo S Imaging Cytometer (Nexcelom Bioscience, Lawrence, MA, USA).

Statistics

Statistical analyses for experimental data were performed in GraphPad (Version 1.0.136) with either two-tailed unpaired t tests or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data are displayed as means ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined at P < 0.05. When a main effect of a one-way ANOVA was found to be statistically significant, a Tukey–Kramer post hoc test was conducted.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Cornell University Division of Nutritional Sciences funds (to A.T.M.), the Cornell University Stem Cell Program (to A.T.M.), a Canadian Institutes for Health Research Doctoral Foreign Study Award (to B.J.G.), the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-1650441 (to J.E.B.) as well as National Institutes of Health under awards R01AG058630 (to B.D.C. and A.T.M.) and R21AR072265 (to B.D.C.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of these funding sources. We are thankful for assistance from the Cornell Biotechnology Resource Center Imaging Facility for the IVIS Spectrum bioluminescence imaging system and acknowledge its support from NIH Award S10OD025049. We are thankful for assistance from the Cornell Center for Animal Resources and Education and the PATh PDX Facility for maintenance of the NSG mouse colony.

Data availability

All RNA-seq and MeRIP-seq data generated or analyzed for the present study are included in this article (including the accompanying Supplementary Tables) and have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus data base (GSE144885).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by A. Emre Sayan

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41420-020-00328-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Lepper C, Partridge TA, Fan CM. An absolute requirement for pax7-positive satellite cells in acute injury-induced skeletal muscle regeneration. Development. 2011;138:3639–3646. doi: 10.1242/dev.067595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almada AE, Wagers AJ. Molecular circuitry of stem cell fate in skeletal muscle regeneration, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:267–279. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dumont NA, Wang YX, Rudnicki MA. Intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms regulating satellite cell function. Development. 2015;142:1572–1581. doi: 10.1242/dev.114223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer, K. D & Jaffrey, S. R. Rethinking m6A readers, writers, and erasers. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol.33, 319–342 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Geula S, et al. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naïve pluripotency toward differentiation. Science. 2015;347:1002–1006. doi: 10.1126/science.1261417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batista PJ, et al. M6A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, et al. N6 -methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:191–198. doi: 10.1038/ncb2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vu LP, et al. The N 6 -methyladenosine (m 6 A)-forming enzyme METTL3 controls myeloid differentiation of normal hematopoietic and leukemia cells. Nat. Med. 2017;23:1369–1376. doi: 10.1038/nm.4416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L, et al. Fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) protein regulates adult neurogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:2398–2411. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, et al. FTO is required for myogenesis by positively regulating mTOR-PGC-1α pathway-mediated mitochondria biogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2702. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kudou, K. et al. The requirement of Mettl3-promoted MyoD mRNA maintenance in proliferative myoblasts for skeletal muscle differentiation. Open Biol.7, 170119 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Mauer, J. et al. Reversible methylation of m6Am in the 5′ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature 541, 371–375 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Giordani L, et al. High-dimensional single-cell cartography reveals novel skeletal muscle-resident cell populations. Mol. Cell. 2019;74:609–621.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dell’Orso, S. et al. Single cell analysis of adult mouse skeletal muscle stem cells in homeostatic and regenerative conditions. Development146, dev174177 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.De Micheli AJ, et al. Single-cell analysis of the muscle stem cell hierarchy identifies heterotypic communication signals involved in skeletal muscle regeneration. Cell Rep. 2020;30:3583–3595.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Ebert D, Huang X, Thomas PD. PANTHER version 14: More genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D419–D426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen X, et al. Genome-wide examination of myoblast cell cycle withdrawal during differentiation. Dev. Dyn. 2003;226:128–138. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delgado I, et al. Dynamic gene expression during the onset of myoblast differentiation in vitro. Genomics. 2003;82:109–121. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(03)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomczak KK, et al. Expression profiling and identification of novel genes involved in myogenic differentiation. FASEB J. 2004;18:403–405. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0568fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson DCL, Dilworth FJ. Epigenetic regulation of adult myogenesis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2018;126:235–284. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cassandri, M. et al. Zinc-finger proteins in health and disease. Cell Death Discov.3, 17071 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Li K, et al. A novel zinc finger protein Zfp637 behaves as a repressive regulator in myogenic cellular differentiation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010;110:352–362. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou J, et al. Dynamic m6A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature. 2015;526:591–594. doi: 10.1038/nature15377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Z, Li Q, Meng R, Yi B, Xu Q. METTL3 regulates alternative splicing of MyD88 upon the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in human dental pulp cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018;22:2558–2568. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engel M, et al. The role of m6A/m-RNA methylation in stress response regulation. Neuron. 2018;99:389–403.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pillon, N. J., Bilan, P. J., Fink, L. N. & Klip, A. Cross-talk between skeletal muscle and immune cells: Muscle-derived mediators and metabolic implications. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab.304, E453–E465 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Arnold L, et al. Inflammatory monocytes recruited after skeletal muscle injury switch into antiinflammatory macrophages to support myogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1057–1069. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodgers JT, Schroeder MD, Ma C, Rando TA. HGFA is an injury-regulated systemic factor that induces the transition of stem cells into GAlert. Cell Rep. 2017;19:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sacco A, Doyonnas R, Kraft P, Vitorovic S, Blau HM. Self-renewal and expansion of single transplanted muscle stem cells. Nature. 2008;456:502–506. doi: 10.1038/nature07384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tierney MT, et al. Autonomous extracellular matrix remodeling controls a progressive adaptation in muscle stem cell regenerative capacity during development. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1940–1952. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cosgrove BD, et al. Rejuvenation of the muscle stem cell population restores strength to injured aged muscles. Nat. Med. 2014;20:255–264. doi: 10.1038/nm.3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilbert PM, et al. Substrate elasticity regulates skeletal muscle stem cell self-renewal in culture. Science. 2010;329:1078–1081. doi: 10.1126/science.1191035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy MM, Lawson JA, Mathew SJ, Hutcheson DA, Kardon G. Satellite cells, connective tissue fibroblasts and their interactions are crucial for muscle regeneration. Development. 2011;138:3625–3637. doi: 10.1242/dev.064162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prigge JR, et al. Nuclear double-fluorescent reporter for in vivo and ex vivo analyses of biological transitions in mouse nuclei. Mamm. Genome. 2013;24:389–399. doi: 10.1007/s00335-013-9469-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao YA, et al. Shifting foci of hematopoiesis during reconstitution from single stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:221–226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2637010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheikh AY, et al. Molecular imaging of bone marrow mononuclear cell homing and engraftment in ischemic myocardium. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2677–2684. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coughlan AM, et al. Myeloid engraftment in humanized mice: Impact of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor treatment and transgenic mouse strain. Stem Cells Dev. 2016;25:530–541. doi: 10.1089/scd.2015.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shultz LD, et al. Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R γ null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells. J. Immunol. 2005;174:6477–6489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rando TA, Blau HM. Primary mouse myoblast purification, characterization, and transplantation for cell-mediated gene therapy. J. Cell Biol. 1994;125:1275–1287. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia G, et al. N6-Methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meng J, et al. A protocol for RNA methylation differential analysis with MeRIP-Seq data and exomePeak R/Bioconductor package. Methods. 2014;69:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4288–4297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webster C, Silberstein L, Hays AP, Blau HM. Fast muscle fibers are preferentially affected in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1988;52:503–513. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90463-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gheller, B. J. et al. Isolation, culture, characterization, and differentiation of human muscle progenitor cells from the skeletal muscle biopsy procedure. J. Vis. Exp.150, e59580 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All RNA-seq and MeRIP-seq data generated or analyzed for the present study are included in this article (including the accompanying Supplementary Tables) and have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus data base (GSE144885).