Abstract

Introduction

This clinical randomized controlled trial evaluates the effectiveness of prednisolone mouthwash as a treatment modality for moderately advanced cases of oral submucous fibrosis.

Materials and Method

Sixty-four patients were enrolled for the study and randomized into two groups (n = 32 in each group). The experimental group was treated with prednisolone mouthwash and antioxidant capsule as per GDCH Nagpur protocol, and control group was treated with antioxidant capsule only. The primary outcome variables were interincisal mouth opening, burning sensation, and recurrent ulceration. Clinical responses were obtained at the time of the allocation, at 1, 3, 6, and 9 months into the intervention, and 6 months thereafter.

Results

The average increased mouth opening achieved was 10.46 mm (p < 0.5) in group A (experimental group) and only 1.04 mm (p < 0.5) mm in group B (control group). In addition, there was a significant difference in relief of burning sensation and recurrent ulceration. Relief of burning sensation and recurrent ulceration was within 12.81 and 10.93 days, respectively, in group A when compared to group B which was within 21.56 and 20.06 days, respectively.

Conclusion

We conclude that in our trial, prednisolone mouthwash with antioxidants was seen to be efficacious, safe, and reliable in the management of oral submucous fibrosis.

Keywords: Oral submucous fibrosis, Prednisolone, Mouthwash, Antioxidant, Interincisal mouth opening, Advanced cases, Prednisone, OSF, osmf

Introduction

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSF) is a chronic slowly progressive disease of oral cavity which is most prevalent in India and East Asia. According to J. J. Pindborg, submucous fibrosis may be defined as an insidious, chronic disease affecting any part of the oral cavity and sometimes the pharynx. Although occasionally preceded by, and/or associated with vesicle formation, it is always associated with a juxta-epithelial inflammatory reaction followed by a fibroelastic change of the lamina propria, with epithelial atrophy leading to stiffness of the oral mucosa and causing trismus and inability to eat [1]. The WHO definition for an oral precancerous condition—”a generalized pathological state of the oral mucosa associated with a significantly increased risk of cancer”—elaborates the characteristics of OSF [2]. The symptoms start from burning sensation in mouth specially while eating spicy food that progresses to recurrent oral ulcerations, pain and stomatitis. On continuation of the habit of areca nut chewing, which is the prime causative agent for this premalignant condition, patients start experiencing stiffness in the muscles of cheek and tongue. This ultimately leads to difficulty in chewing food, swallowing and reduced mouth opening. Patients often present with hollowing of cheeks, decreased mobility and depapillation of tongue, blanching of oral mucus membrane and fibrous bands palpable with respect to buccal mucosa and circumoral region. If not addressed well, it ultimately leads to change in voice, malnourishment and predispose to cancerous conditions. A wide range of treatment methods including medical and surgical interventions, physiotherapy, lifestyle modification or a combination of any of these are now being used for the treatment of OSF in clinical practice [3].

As we already know, moderate and advanced cases of OSF are managed surgically, but these have been reported with varying results [4, 5]. Early and low-grade OSF is managed by various medicinal treatments, which aim at providing relief to a certain extent in signs and symptoms of OSF. Their results are often variable and patient dependent. In addition, among the medical methods, locally injected intralesional steroids, especially glucocorticoids such as hydrocortisone, triamcinolone, betamethasone, and dexamethasone, have been highly popular in management of OSF mainly for two reasons—reduction in profibrotic inflammation and the enhancement of profibrolytic immune-mediated pathways [6].

Hence, the surgeon is always in dilemma regarding the treatment of choice for moderately advanced cases, leading to a paradigm shift toward finding alternative management. We therefore used prednisolone which has already been in use for the treatment of other oral lesions [7, 8], to assess the effectiveness of it as an alternate treatment modality for moderately advanced cases of OSF by evaluating the degree of improvement in interincisal mouth opening and relief of oral symptoms following steroid therapy. Prednisolone is a potent, intermediate acting corticoid that is available in the form of dispersible tablets and easily available in the market. The form of prednisolone used in our study is as a mouthwash, which is a topical form of delivering the drug through oral mucosa, and thus will have minimal side effects if used for the long term. Its intralesional injections have proven to be traumatic and have effects lasting only for intermediate time period and ultimately lead to fibrosis of the mucus membrane at the sites of injection, thus worsening the prognosis of the condition in the long term. Thus, mouthwash form of prednisolone was chosen as the treatment of choice in our study. The dosage taken is according to 1 mg/kg body weight where mean study population has weight of 60 kg, thus and, 20 mg thrice (total 60 mg) was delivered in a tapering dose.

The primary aim of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of prednisolone in the management of moderately advanced oral submucous fibrosis in terms of relief of symptoms associated with the disease and interincisal mouth opening.

Patients and Methods

Indian subjects with oral submucous fibrosis who had stopped betel nut chewing for 3 months or more were enrolled for a randomized clinical controlled study. They were all provided with full information about the treatment and its adverse effects, especially of corticosteroids and of carotenodermia [9].

An informed consent was then obtained from them. Scientific and institutional ethical committee was informed and approved the protocol for the study.

Study Patients

Over a two and half year period, the authors identified 102 subjects with oral submucous fibrosis who were eligible for the study. The target disease was clinically diagnosed as oral submucous fibrosis based on criteria given by Khanna and Andrade [4].

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

Age between 15 and 40 years.

Group III with moderately advanced cases of OSF (interincisal mouth opening 15–25 mm)

Agreement not to use other curative agents during the procedure and

Willingness to follow the investigator’s instructions exactly.

Patients with traumatic ulcers from malposed third molars, those with trismus caused by other reasons, such as inflammation (as a result of pericoronitis, dental abscesses, or aphthous ulceration), oral malignancy, those who had previous treatment for OSF, and those with any systemic disorder or pregnancy and lactation were excluded from the study. Patients who had a history of non-compliance to medical regimens or who were considered potentially unreliable or will not be able to complete the entire study and patients who were part of or have participated in any clinical investigation with an investigational drug within 1 month prior to dosing were also excluded from the current study.

Among the 102 eligible cases, 36 refused to consent to the study because of concerns taking any long-term medication, or because of anxiety over the adverse effects reported in previous studies [8] and listed in the information sheet. Two were ineligible at the time of first interview as a result of recent history of chewing betel nuts or not being able to stop chewing it. The subjects were instructed to strictly adhere to tobacco avoidance.

Intervention

Each patient was counseled on complete discontinuation of the habit. Every registered patient was treated with the ‘intention to treat principle.’ They were numbered sequentially from 1 to 64 according to the time of enrollment. Thirty-two numbers were selected from a random number table generated by computer and the patients with the numbers selected were assigned to one study group and the remaining 32 patients were assigned to the other. The experimental group (group A) patients were treated with dispersible tablet prednisolone 20 mg as a mouthwash and antioxidant capsule (alpha lipoic acid 100 MG, beta carotene 20 MG, elemental copper 2 MG, elemental selenium 150 MCG, lycopene 10 MG, vitamin E 20 IU, zinc sulfate 54.9 MG per day) as per the GDCH Nagpur protocol for advanced cases of oral submucous fibrosis (Table 1) and instructions as given in (Table 2). The control group (group B) patients were treated with only the aforementioned antioxidant capsule.

Table 1.

Treatment protocol for advanced cases of oral submucous fibrosis

| 1st month | 2nd month | 3rd month | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 day | 10–20 day | 20–30 day | ||

| 60 MG (20 mg TDS) Tab Prednisolone + Cap Antioxidants BD | 40 MG (20 mg BD) Tab Prednisolone + Cap Antioxidants BD | 20 MG (20 mg OD) Tab Prednisolone + Cap Antioxidants BD | Cap Antioxidants BD | Cap Antioxidants BD |

Protocol should be repeated 2 times after completion of one

Table 2.

Information sheet about the oral use of prednisolone as mouthwash

| 1. | Use one 20 mg tablet and dissolve it in 10–20 ml of water. (Always make up a fresh mixture and use it straight away) |

| 2. | Hold the mixture in your mouth, especially around buccal mucosa, palate region for a time 5–10 min |

| 3. | Please spit out after using it in the mouth as a rinse |

| 4. | Always use after mealtimes so that it remains coating your mouth as long as possible |

| 5. | You need to get a repeat prescription from doctor before starting the next regime |

Clinical Assessment and Data Collection

The 20 mg dispersible tablet prednisolone used as a mouthwash and antioxidants therapy were prescribed to the experimental group for 9 months, followed by a 6-month follow-up of the patients to evaluate its clinical response. The patients were followed up on the monthly basis for counseling regarding the habit and whether they were taking medications as per the protocol. They were also questioned regarding the relief of their symptoms in every monthly visit. Three parameters were assessed for each subject: interincisal mouth opening, burning sensation, and recurrent ulceration. Mouth opening was measured as the interincisal distance from the incisal edge of the upper central incisor tooth to the incisal edge of the lower central incisor tooth. The measurement was made using a stainless steel scale and recorded in millimeters. Burning sensation and recurrent ulceration was recorded as persistent, reduced, or absent at every visit based on patient’s response and clinical examination. Patients reported the number of days after which they stopped having new ulcers and burning sensation, and the data were mentioned in the patient’s chart. Digital photographs of all participants were obtained at the time of the allocation, at 3 and 6 months into the intervention, at the completion of the intervention, and 6 months thereafter. Clinical responses were assessed at the end of the 9-month trial period and at the end of the 6-month observation period. The response evaluation and measurements were performed by a trained maxillofacial surgeon who was not the part of the study and blinded to the groups of the patients.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 16 was used for data analysis. Post hoc Tukey’s test was used for comparison of mean interincisal mouth opening at baseline and different follow-ups within each group. Statistical significance was kept at p value ≤ 0.05.

Result

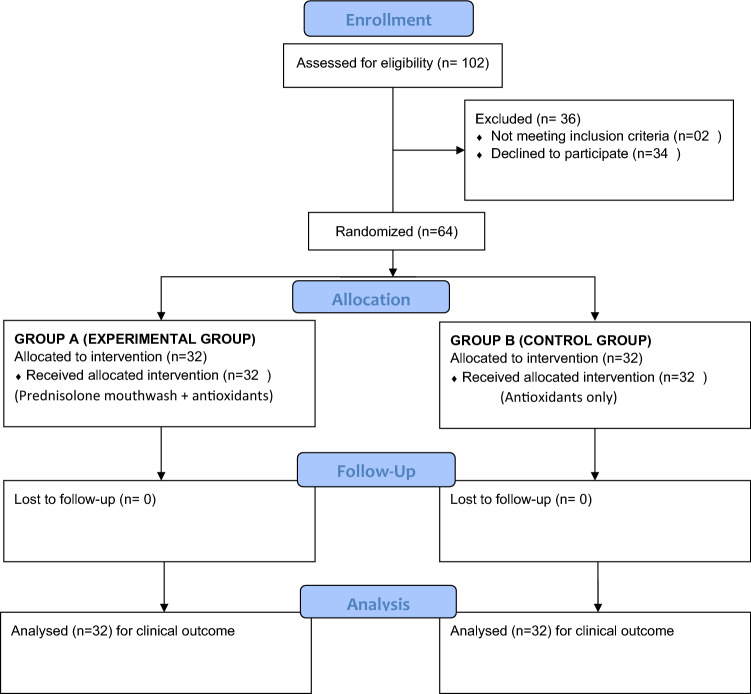

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 64 participants (Fig. 1) (45 male, 21 female; mean age 28.03 years, range 16–38 years) were enrolled for the study. All the participants who completed the study adhered to strict protocol required as per the trial. The intragroup and intergroup analysis of improvement is shown in Table 3 that was statistically significant for both the groups.

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram

Table 3.

Intragroup and intergroup analysis of interincisal mouth opening change from initial to 6-month follow-up

| Timeline | Group A | Group B | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Initial | 21.3 (2.5) | 20.5 (2.6) | 0.22 |

| 3 months | 23.7 (2.9) | 21 (3) | 0.001 |

| 6 months | 26.5 (3.1) | 21.3 (3.1) | < 0.001 |

| 9 months | 30.2 (4.4) | 21.9 (3.4) | < 0.001 |

| 6 month follow-up | 31.7 (4.9) | 21.5 (3.1) | < 0.001 |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Post hoc Tukey’s test | Initial < 3 month < 6 month < 9 month < 6 month follow-up | Initial < 3 month < 6 month < 9 month < 6 month follow-up |

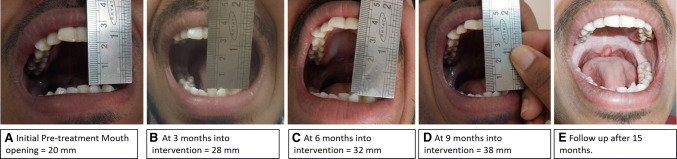

Mean score of interincisal mouth opening of group A at baseline was 21.25 mm while at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 15 months after treatment with prednisolone and antioxidants combination was 23.52 mm, 23.17 mm, 26.53 mm, 30.21 mm, and 31.71 mm, respectively. On the contrary, mean score of interincisal mouth opening of group B at baseline was 20.46 mm while at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 15 months after treatment with antioxidants was 20.62 mm, 21.03 mm, 21.31 mm, 21.87 mm, and 21.50 mm, respectively. The average increased mouth opening achieved was 10.46 mm (p < 0.5) in group A (experimental group) and only 1.04 mm (p < 0.5) mm in group B (control group). After 15 months of recall visits, pair-wise comparison by post hoc Tukey’s test showed that mean scores of interincisal mouth opening at baseline of group A are significantly higher from group B. Figure 2 demonstrates the initial pre-treatment as well as the gradual change in the mouth opening during the treatment under Group A.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of gradual increase in mouth opening during the trial study period

In addition, relief of symptoms was inquired from all the patients during their monthly visit and there was a significant difference in relief of burning sensation and recurrent ulceration within 12.81 and 10.93 days, respectively, in group A when compared to group B which was 21.56 and 20.06 days, respectively.

None of the patients reported any adverse reactions of the experimental drugs during the trial period. The clinician reported no signs of any adverse effects like change in color, aggravated ulcerations, or any systemic complications during the follow-up visits.

Patient compliance was good throughout the study period. We lost no patient during follow-up probably because of monthly recall and counseling.

Discussion

The results of this trial show that a commercially available, inexpensive, and well-tolerated prednisolone tablets when used as a mouthwash are effective in the relief of severity of symptoms of oral submucous fibrosis, especially grade III. Patient-reported outcomes are ability to maintain a normal diet, gradual increase in mouth opening, and relief in recurrent ulcerations as well as burning sensation further substantiated the efficacy of prednisolone mouthwash. This trial has further led to a favorable way of treating a debilitating condition with the most conservative and patient-friendly manner.

OSF is predominantly seen in South and South East Asia or among those in diaspora originating from these countries. Various factors associated with the etiology of OSF include areca nut (most common), red chilies (capsaicin), tobacco, nutritional deficiency and genetics [10].

The specific etiology of OSF remains to be elucidated, although several pathophysiologies have been suggested including increased collagen synthesis by fibroblast, inhibition of collagenase enzyme and fibrinolytic system, and the adverse effects on local tissue architecture caused by the metabolic intermediates from betel nut [11–13].

Treatment protocol depends on groups who are categorized into four stages according to interincisal mouth opening, alteration in mucosa, distribution of fibrous band, and malignant transformation. Medical intervention was considered to be solution for early stages but partially relieved patients of their symptoms, as confirmed in many studies [4, 5], and have very inconsistent outcomes and are still not satisfactory. However, in stage III patients, the medical modality is not sufficient to achieve restoration of function. In this group of patients, surgical intervention should be kept as the second option [14].

Various surgical modalities have been quoted in the literature with variable results which aims at improving mouth opening by release of the fibrous bands, temporalis myotomy and coronoidectomy [4, 15]. This can be followed by introduction of remote tissues (such as a buccal fat pad [16], nasolabial [17] or platysmal flaps [18], or free tissue transfer) in the resultant defects. The success of surgical management depends to a great extent on the postoperative physiotherapy for mouth opening and the patient’s compliance for the same [18, 19]. Despite this wide range of treatment options, there is no reliable evidence for the effectiveness of any of them and no single modality has been identified to cure Grade III OSF [20].

The presumption that the pathophysiology of the disease involves inflammatory reactions supports the use of steroids, antioxidants, interferon gamma or anti-inflammatory placental extracts, dietary supplementation, and injection of derivative enzymes to facilitate fibrous tissue removal [6, 14, 15]. However, the progressive nature of the disease and lack of awareness regarding the disease pathogenesis coupled with the limited routes of administration make it difficult for a single drug to reverse the OSF progression [6].

Various steroid preparations like intralesional or topical has been shown to be efficacious in ameliorating oral symptoms [14], but it was found that the mechanical insults due to insertion of injection needles [6, 21] and the chemical irritation caused by the injected fluids aggravate fibrosis, trismus, dysphagia, and other morbidity after a period of time. Oral route of medicaments limits the concentration of drug delivery [3, 14]. This is the reason why intralesional injections were not preferred in the present study.

Moreover, it is well known that corticosteroids have different dose-dependent effects on different tissues due to their mechanism of action. Systemic corticosteroids are rarely used for the treatment of OSF because of their side effects and are only reserved for those with severe, refractory disease. Owing to progressive nature of OSF, we used the dose of 60 mg tablet prednisolone as a mouthwash for first 10 days and then tapered to 40 mg for next 10 days followed by 20 mg for next 10 days. To reduce adverse effects of prolonged use of corticosteroid, we gradually tapered off the dose of prednisolone over 1 month and discontinued it for a further 2 months. This whole 3-month regimen was repeated two times to achieve the best possible results. Among the glucocorticoids, prednisolone (prednisone) was used in our trial as it has already been in use for the treatment of other oral lesions with significant favorable results [7, 22].

Various studies also have emphasized over the use of antioxidant group of drugs for such cases [3, 6, 7, 23]. An effective increase in mouth opening and tongue protrusion with beta carotene and vitamin was observed by Gupta et al. [13]. Lycopene, a natural carotenoid with antioxidant and anti-proliferative properties, is very efficacious in improving clinical symptoms of multiple oral conditions. Apart from the mouth opening, the other complaints such as burning sensation, recurrent stomatitis, and intolerance to spicy foods are usually addressed by the administration of multivitamins and dietary supplements as first-line therapy for initial submucous fibrosis [6, 24].

Interincisal mouth opening was the most commonly measured outcome across the majority of studies as primary outcome. In our trial study, mouth opening improvement ranged from 7 to 17 mm, with 10.46 mm as the mean in group A. This change in the mean mouth opening was considered to be statistically significant. Follow-up done at monthly intervals illustrated a maintenance of this improvement from 3rd and 6th months into the intervention, at the completion of the intervention, and 6 months thereafter. In comparison with group A, the average improvement in group B patients was only 1.14 mm, with the minimum and maximum values being 0 mm and 4 mm, respectively. This change was found to be statistically significant. Although the improvement was statistically significant, it was not clinically significant.

In terms of burning sensation, group A showed a relief in 12.81 days compared to Group B which showed improvement in 21.56 days. Group A patients also reported a better response to recurrent ulcerations in 10.93 days compared to patients in Group B that reported relief in recurrent ulcerations in mean 20.06 days (Table 4).

Table 4.

Improvement in other clinical response in Group A and Group B

| Clinical response | Group A | Group B | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Recurrent ulceration | 10.9d (2.7) | 20.1d (6) | < 0.001 |

| Burning sensation | 12.8d (4.6) | 21.6d (4.5) | < 0.001 |

d = Days

Our results indicate that antioxidants are indeed effective in reducing associated symptoms but not effective for improvement in mouth opening. Topical corticosteroids (prednisolone) proved to be reliable in treating all the symptoms of OSF including significant relief of trismus. On comparing the results of the experimental and the control group, it is inferred that an effective management of a debilitating condition is very much possible if we combine two separate potent therapeutic agents. Patient satisfaction in terms of maintaining a normal diet and mouth opening is achieved conservatively and for long duration.

Although steroids have been used before in the treatment of OSF through various routes of administration for quite a long time, its administration via mouthwash is definitely a novel approach in the management of OSF. This modality has many benefits. Firstly, dispersible prednisolone tablets are easily available and affordable. It is a noninvasive treatment modality especially for the borderline cases. Also, in elderly patients or patients in whom a non-compliance may be obtained for post-surgery physiotherapy, this approach serves as better option to avoid surgery.

Limitations of the Study

This clinical trial was subject to certain limitations. Firstly, histological changes after treatment were not evaluated because most patients refused to undergo a biopsy at the end of therapy. Secondly, a completely blank control group was not set up for this trial due to patient refusal. Moreover, there were ethical concerns regarding the chances of malignant transformation if only placebo was given. Thirdly, as a preliminary clinical trial, the dosage and frequency of prednisolone mouthwash were decided according to various previously reported trials [25–27].

In the present study, a favorable clinical response was obtained from patients with the use of a combination of prednisolone mouthwash and antioxidants rather than antioxidants alone. This combination was found to be effective and yielded superior results in management of OSF. Further investigations should be carried out to determine the safety and effectiveness of these affordable and most importantly, noninvasive interventions for the treatment of OSF.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

“All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards”. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Abhay Datarkar, Email: abhaydatarkar@yahoo.com.

Abhishek Akare, Email: abhiakre@gmail.com.

Shikha Tayal, Email: daringshikha@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Pindborg JJ, Sirsat SM. Oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;22(6):764–779. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(66)90367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajendran R. Oral submucous fibrosis: etiology, pathogenesis, and future research. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72(6):985. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerr AR, Warnakulasuriya S, Mighell AJ, Dietrich T, Nasser M, Rimal J, Jalil A, Bornstein MM, Nagao T, Fortune F, Hazarey VH. A systematic review of medical interventions for oral submucous fibrosis and future research opportunities. Oral Dis. 2011;17:42–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanna JN, Andrade NN. Oral submucous fibrosis: a new concept in surgical management: report of 100 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;24(6):433–439. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80473-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Passi D, Bhanot P, Kacker D, Chahal D, Atri M, Panwar Y. Oral submucous fibrosis: newer proposed classification with critical updates in pathogenesis and management strategies. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2017;8(2):89. doi: 10.4103/njms.NJMS_32_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang X, Hu J. Drug treatment of oral submucous fibrosis: a review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(7):1510–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carbone M, Goss E, Carrozzo M, Castellano S, Conrotto D, Broccoletti R, Gandolfo S. Systemic and topical corticosteroid treatment of oral lichen planus: a comparative study with long-term follow-up. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32(6):323–329. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.González-Moles MA, Scully C. Vesiculo-erosive oral mucosal disease—management with topical corticosteroids: (2) protocols, monitoring of effects and adverse reactions, and the future. J Dent Res. 2005;84(4):302–308. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagao T, Warnakulasuriya S, Nakamura T, Kato S, Yamamoto K, Fukano H, Suzuki K, Shimozato K, Hashimoto S. Treatment of oral leukoplakia with a low-dose of beta-carotene and vitamin C supplements: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(7):1708–1717. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tilakaratne WM, Ekanayaka RP, Warnakulasuriya S. Oral submucous fibrosis: a historical perspective and a review on etiology and pathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(2):178–191. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tilakaratne WM, Klinikowski MF, Saku T, Peters TJ, Warnakulasuriya S. Oral submucous fibrosis: review on aetiology and pathogenesis. Oral Oncol. 2006;42(6):561–568. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajalalitha P, Vali S. Molecular pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis: a collagen metabolic disorder. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34(6):321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S, Reddy MV, Harinath BC. Role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in aetiopathogenesis and management of oral submucous fibrosis. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2004;19(1):138. doi: 10.1007/BF02872409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rai S, Rattan V, Gupta A, Kumar P. Conservative management of Oral Submucous Fibrosis in early and intermediate stage. J Oral Biol Craniofacial Res. 2018;8(2):86–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warnakulasuriya S, Kerr AR. Oral submucous fibrosis: a review of the current management and possible directions for novel therapies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(2):232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma R, Thapliyal GK, Sinha R, Menon PS. Use of buccal fat pad for treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(1):228–232. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambade P, Meshram V, Thorat P, Dawane P, Thorat A, Rajkhokar D. Efficacy of nasolabial flap in reconstruction of fibrotomy defect in surgical management of oral submucous fibrosis: a prospective study. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;20(1):45–50. doi: 10.1007/s10006-015-0519-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bande CR, Datarkar A, Khare N. Extended nasolabial flap compared with the platysma myocutaneous muscle flap for reconstruction of intraoral defects after release of oral submucous fibrosis: a comparative study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51(1):37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta D, Sharma SC. Oral submucous fibrosis—a new treatment regimen. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46(10):830–833. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angadi PV, Rao S. Management of oral submucous fibrosis: an overview. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;14(3):133–142. doi: 10.1007/s10006-010-0209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borle RM, Borle SR. Management of oral submucous fibrosis: a conservative approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49(8):788–791. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lozada F, Frey FJ, Benet LZ. Prednisolone clearance: a possible determinant for glucocorticoid efficacy in patients with oral vesiculo-erosive diseases. J Dent Res. 1983;62(5):575–577. doi: 10.1177/00220345830620051401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh M, Krishanappa R, Bagewadi A, Keluskar V. Efficacy of oral lycopene in the treatment of oral leukoplakia. Oral Oncol. 2004;40(6):591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar A, Bagewadi A, Keluskar V, Singh M. Efficacy of lycopene in the management of oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 2007;103(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.http://www.bhamcommunity.nhs.uk/EasySiteWeb/GatewayLink.aspx?alId=12046

- 26.https://www.drugs.com/pro/prednisone.html

- 27.https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02229136