Abstract

Objectives

The aim of our study is to evaluate the influence of patient risk factors and the length of surgical time on the onset of BPPV (benign paroxysmal positional vertigo) and suggest surgical and clinical strategies to prevent this rare complication.

Method

Our retrospective study analyzes that, in 2 years, 281 patients, divided into three groups, underwent wisdom teeth extraction, sinus lift elevation and orthognathic surgery, at the Oral and Maxillofacial Department of the University of Naples “Federico II.”

Results

Twenty-one patients presented postoperative BPPV. Some comorbidities, like dyslipidemia, high cholesterol levels, vascular problems, endocrinological disorders, perimenopausal age, female gender, cranial trauma, neurologic disorders, migraine, hypovitaminosis D, autoimmune disease, flogosis of inner ear, can be risk factors to the occurrence of postoperative vertigo.

Conclusion

Our statistical analysis revealed a relationship between surgical time and comorbidity and onset of vertigo for each group of patients.

Keywords: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Etiology, Surgical trauma, Oral and maxillofacial surgery

Introduction

Positional vertigo is a feeling of spinning when the patient turns the head in a particular manner or assumes a certain position [1].

The etiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is unknown. About 20% of cases have been associated with minor and major head and neck traumas; few cases were associated with oral or maxillofacial procedures [2].

Preparation of implant beds or sinus floor elevation procedures, impacted wisdom teeth extraction, osteotomies during orthognathic surgery with the aid of osteotomes and surgical mallets transmits percussive and vibratory forces capable of detaching the otoliths, causing them to float around in the endolymph producing BPPV [3].

BPPV is usually unilateral; episodes associated with head trauma are bilateral as well as some cases of bilateral vertigo after orthognathic surgery [4].

The common postoperative complications of extraction of wisdom teeth, orthognathic surgery and sinus floor lift are: infection, injury to neighboring vessels, nerve injuries, bad fractures, acute or chronic sinusitis, implant failure, Schneiderian membrane perforation and so on [5–8].

The postoperative BPPV is a less common complication less described in the scientific literature; however, oral and maxillofacial surgeons should consider it.

The aim of our study is to evaluate the influence of specific comorbidities on the onset of BPPV and the relation between the length of surgical time and the onset of BPPV. Furthermore, we propose some surgical and/or clinical strategies to prevent this complication.

Materials and Methods

From January 2015 to December 2016, 301 patients underwent wisdom teeth extraction, sinus lift elevation and orthognathic surgery, at the Oral and Maxillo Facial Department of University of Naples “Federico II.”

Patients lost during follow-up or BPPV sintomatology for over 15 days from surgery, or previous surgical treatment for facial traumas, or previous BPPV or previous labyrinth disorders were excluded (20 patients).

For this retrospective analysis, 281 subjects (180 males and 101 females, average age of 41.5) were enrolled; of these, 21 patients presented postoperative BPPV.

All surgical procedures required osteotomes and/or mallets and/or rotating tools.

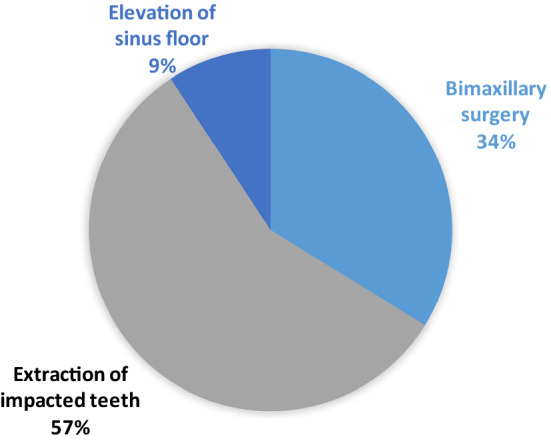

Features of selected patients are outlined in Table 1. All patients were divided into three groups: 95 patients (67 males and 28 females) underwent bimaxillary surgery for dentoscheletric malocclusion (Group I); 160 patients (97 males and 63 females) underwent extraction of impacted teeth of 3.8 and 4.8 through the erosion of the incarcerating bony wall (Group II); and 26 patients (16 males and 10 females) underwent preparation of implants bed with elevation of sinus floor (Group III) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Clinical data of patients enrolled for the study

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 25–69 (mean 41.5) |

| Sex | Male n = 180 |

| Female n = 101 | |

| Surgical technique | Orthognathic surgery (Group 1) n = 95 |

| Third molar extraction 3.8, 4.8 (Group 2) n = 160 | |

| Sinus lift (Group 3) n = 26 | |

| BPPV onset | Group 1 n = 4; bilateral n = 4; unilateral n = 0 |

| Group 2 n = 14; bilateral n = 11; unilateral n = 3 | |

| Group 3 n = 3; bilateral n = 0; unilateral n = 3 | |

| Presence of comorbidities | Group 1 n = 31 |

| Group 2 n = 75 | |

| Group 3 n = 16 | |

Fig. 1.

Surgical techniques performed on enrolled patients

All patients were subjected to bed-side examination, posterior nystagmus was evaluated, and cases of BPPV were identified through the involvement of vertical or lateral channels.

The diagnosis of postoperative BPPV was made, under Frenzel glasses or videoculoscopy control, using the typical positioning maneuvers of Hallpike for the posterior semicircular canal (PSc) and Pagnini [9] and Mc Clure’s maneuvers [10] (slow positioning on the sides) for the lateral semicircular canal (lSc).

The canalith repositioning procedure (CRP) through Epley maneuver [11] was performed for all patients with postoperative BPPV.

Patients’ follow-up was scheduled for 3, 6 and 12 months after Epley maneuver.

Data were aggregated with Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet, and statistical analysis was performed using statistical packages software system 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Fisher double-tailed test has been used to evaluate statistical relationship between surgical time with comorbidity and onset of vertigo.

Results

Vestibular pathology has been recorded on the side submitted to surgical treatment in 6 cases: 2 males and 1 female underwent extraction of impacted teeth, and 1 male and 2 females underwent preparation of implants bed with unilateral elevation of sinus floor. There was evidence of bilateral pathology with simultaneous involvement of multiple semicircular canals in 15 cases: 2 females and 2 males underwent bimaxillary surgery, and 7 males and 4 females underwent extraction of impacted teeth (3.8 and 4.8).

The mean onset time of postoperative BPPV was 3.61 days. The most rapid onset was reported in a 60-year-old female, 8 h after extraction of 1.8 and 4.8 impacted teeth. The most remote onset was reported in a 68-year-old female 7 days after extraction of 4.8 impacted teeth.

Fisher test conducted for each group of patients revealed a statistical dependence as shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Table 2.

Analysis of risk factors associated with the onset of BPPV for patients that underwent orthognathic surgery (Group 1) (Fisher exact test both tails for p = 0.05)

| Risk factors | + BPPV (n =) | − BPPV (n =) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities | |||

| Presence | 1 | 30 | 0.621 |

| Absence | 3 | 35 | |

| Surgical time | |||

| > 3 h | 4 | 25 | 0.007 |

| < 3 h | 0 | 66 | |

Table 3.

Analysis of risk factors associated with the onset of BPPV for patients that underwent third molar avulsion (Group 2) (Fisher exact test both tails for p = 0.05)

| Risk factors | + BPPV | − BPPV | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities | |||

| Presence | 6 | 69 | 1 |

| Absence | 8 | 91 | |

| Surgical time | |||

| > 45 min | 9 | 43 | 0.014 |

| < 45 min | 5 | 103 |

Table 4.

Analysis of risk factors associated with the onset of BPPV for patients that underwent sinus lift (Group 3) (Fisher exact test both tails for p = 0.05)

| Risk factors | + BPPV (n=) | − BPPV (n=) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities | |||

| Presence | 3 | 7 | 0.046 |

| Absence | 0 | 16 | |

| Surgical time | |||

| > 1.5 h | 2 | 9 | 0.555 |

| < 1.5 h | 1 | 14 |

After Epley maneuver, a negative clinical pattern was confirmed in all cases at 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up.

Discussion

The inner ear is formed by the osseous labyrinth and the membranous labyrinth. The osseous labyrinth is contained in the petrous portion of the temporal bone; it is formed by the vestibule, semicircular canals and the cochlea. These bone cavities are lined with a very thin fibroserous membrane filled with the perilymph. The semicircular canals and vestibule contain equilibrium receptors. Receptors in the semicircular canals respond to alterations in direction of head movement. During head rotation, the endolymph in the semicircular canals slows down and then moves in the opposite direction to the head’s movement causing stimulation of hair cells that send an impulse to the cerebellum through the vestibular nerve. The vestibule contains macula receptors that sense the body’s static equilibrium. Otoliths move with head position and stimulate the hair cells that in turn transmit a signal to the brain to sense balance in the vestibule [1, 2].

The BPPV is an attack of rotatory vertigo, induced by changes in the head position relative to gravity. Typical signs of BPPV are a paroxysmal nystagmus, torsional and directed upwards, for the PSc, horizontal and geotropic or apogeotropic for lSc.1 The criteria used for the diagnosis were: a paroxysmal nystagmus with brief latency, accompanied by exhaustible, repeatable and fatigable vertigo. Each vertigo episode appears with short latency, lasts for less than a minute and is characterized by an increase followed by a decrease in its intensity. The vertigo is associated with neurovegetative symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, tachycardia and anxiety, without any cochlear symptoms such as hearing loss, tinnitus or ear fullness [2].

The etiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is unknown; 15–20% of cases have been associated with minor and major head trauma; few cases were associated with oral or maxillofacial procedures. Sinus floor elevation procedures, wisdom teeth avulsion, maxillary and mandibular osteotomies performed with osteotomes and surgical mallets transmit percussive and vibratory forces capable of detaching the otoliths, causing them to float around in the endolymph, hence determining BPPV [1–5, 12–14]. The BPPV is usually unilateral; the episodes associated with head trauma and orthognathic surgery are bilateral [15], as in our sample.

In our sample, for patients that underwent orthognathic surgery and third molar extraction (Group 1 and Group 2) emerges a statistical correlation between the length of surgical time and the onset of BPPV (Table 2, p = 0.007, Table 3, p = 0.014).

The patient’s surgical head position, with hyperextended head, the length of surgical time with a repeated percussive and vibratory stress help the displacement of these free-floating particles into the posterior semicircular canal; when the patient later adopts a seated position, the otoconia descend into the ampullary crest, triggering an anomalous stimulus causing vertigo (BPPV). The postoperative BPPV is characterized by short-term recurrent episodes of vertigo associated with intense nystagmus, due to the anatomical features of the district involved. BPPV risk factors (comorbidities), like dyslipidemia, high cholesterol levels, vascular problems, endocrinological disorders, perimenopausal age (50–60 years), sex (female gender), cranial trauma, neurologic disorders, migraine, hypovitaminosis D, autoimmune disease, flogosis of inner ear, may promote the occurrence of postoperative vertigo [16–23].

In our sample, for patients that underwent preparation of bed implant through sinus floor lift (Group 3) emerges a statistical correlation between the presence of comorbidities and the onset of BPPV (Table 4, p = 0.046).

The criteria commonly approved for the diagnosis of BPPV are a paroxysmal nystagmus with brief latency, accompanied by exhaustible, repeatable and fatigable vertigo. The diagnosis is made, under Frenzel glasses or videoculoscopy control, using the typical positioning maneuvers of Hallpike and Pagnini and Mc Clure’s maneuvers (slow positioning on the sides) for the lateral semicircular canal (lSc).

Specifically, in posterior canal type of BPPV, a torsional nystagmus is present, with additional vertical upward component, in which the upper pole of the eye rotates toward the affected ear. Such nystagmus is induced by the Dix–Hallpike maneuver [24], while in lateral canal type of BPPV, geotropic nystagmus is present, induced by the supine roll test. The rightward horizontal nystagmus is induced by the right-ear-down head position, while leftward horizontal nystagmus is induced by the left-ear-down head position, with the patient supine in the geotropic variant and leftward horizontal nystagmus induced by the right-ear-down head position and rightward horizontal nystagmus induced by the left-ear-down head position in apogeotropic variant [25]. There are several reports of BPPV following osteotome sinus floor elevation [14, 3, 13, 26, 10, 27, 28].

Di Girolamo et al. [3] analyzed 146 patients who underwent osteotome sinus floor elevation; 4 patients of 146 developed BPPV 1 or 2 days after the surgical procedure, which was solved with the Epley repositioning maneuver.

Sammartino et al. [28] showed that 3 of 98 patients who underwent sinus floor elevation with osteotome and mallet developed BPPV but none of the 98 patients who underwent sinus floor elevation without the use of a mallet.

Moreover, Chiarella et al. [2] showed that dentoalveolar surgery with a rotating bur for removal of impacted teeth and cysts could lead to BPPV.

Furthermore, Beshkar et al. [1] analyzed 50 patients who underwent orthognathic surgery and showed 1 case of BPPV positive on Dix–Hallpike test subsequently treated by a neurologist.

Vannucchi et al. [29] explained that the treatment for BPPV is expected by the canalith repositioning procedure (CRP), such as modified Epley maneuver for the treatment of the posterior canal type of BPPV, in which the specific sequential head movements cause otoconial debris to move from the posterior semicircular canal to the utricle. Specifically, after rotating the head to the affected ear, the patient is moved from the sitting position to supine position, with their head tilted back of about 45°. Subsequently, after 30 s, the head is moved to the other side and then the patient’s trunk is turned in the opposite direction to the affected ear. Then, after additional 30 s, the patient is placed in sitting position.

Conclusion

The postoperative BPPV is a less common complication that should be considered by oral and maxillofacial surgeons.

We propose, in the treatment of patients with risk factors to the postoperative BPPV, some surgical and/or clinical strategies to prevent this complication:

Use piezoelectric and endoscopic aid to reduce vibration and percussion stress in long and complicated surgery;

Limit the hyperextension of the head during surgery;

Advise on a semi-deployed (double pillow use) position, during postoperative times, even during night rest.

Finally, patients should always be informed about the possible BPPV postoperative complication in order to prevent legal disputes.

In further studies, with an enlargement of the sample, it would be appropriate to evaluate the ocular vemps (vestibular evoked myogenic potentials) and the cervical vemps through the video head impulse test. The possible irreversible saccular and utricular otolithic dysfunction caused by the surgical insult could be related to the clinical substrate (comorbidity).

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Beshkar M, Hasheminasab M, Mohammadi F. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo as a complication of orthognathic surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41(1):59–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiarella G, Leopardi G, De Fazio L, Chiarella R, Cassandro E. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo after dental surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265(1):119–122. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0397-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Girolamo M, Napolitano B, Arullani CA, Bruno E, Di Girolamo S. Paroxysmal positional vertigo as a complication of osteotome sinus floor elevation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262(8):631–633. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0879-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furman JM, Cass SP. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(21):1590–1596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911183412107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flanagan D. Labyrinthine concussion and positional vertigo after osteotome site preparation. Implant Dent. 2004;13(2):129–132. doi: 10.1097/01.ID.0000127527.44561.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friscia M, Sbordone C, Petrocelli M, Vaira LA, Attanasi F, Cassandro FM, Paternoster M, Iaconetta G, Califano L. Complications after orthognathic surgery: our experience on 423 cases. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;21(2):171–177. doi: 10.1007/s10006-017-0614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friscia M, Petrocelli M, Sbordone C, Corvino R, Maglitto F, Cassandro FM, Iaconetta G, Califano L (2017) Retained upper third molars during Le Fort I osteotomy with downfracture. Ann Ital Chir 88 [PubMed]

- 8.Reddy KS, Shivu ME, Billimaga A. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo during lateral window sinus lift procedure: a case report and review. Implant Dent. 2015;24(1):106–109. doi: 10.1097/ID.0000000000000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pagnini P, Nuti D, Vannucchi P. Benign paroxysmal vertigo of the horizontal canal. ORL. 1989;51:161–170. doi: 10.1159/000276052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McClure JA. Horizontal canal BPV. J Otolaryngol. 1985;14(1):30–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epley JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107(3):399–404. doi: 10.1177/019459989210700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim JH, Kim HJ, Kang JW. Bilateral benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: an unusual complication of orthognathic surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51(8):e291–e292. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.05.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penarrocha M, Perez H, Garcia A, et al. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo as a complication of osteotome expansion of the maxillary alveolar ridge. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:106–107. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.19307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saker M, Ogle O. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo subsequent to sinus lift via closed technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1385–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.05.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan DM, Attal U, Kraus M. Bilateral benign paroxysmal positional vertigo following a tooth implantation. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117:312–313. doi: 10.1258/00222150360600959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peñarrocha M, Garcia A. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo as a complication of interventions with osteotome and mallet. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(8):1324. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes CA, Proctor L. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1997;107(5):607–613. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iorio N, Sequino L, Chiarella G, Cassandro E. Database of benign positional paroxysmal nystagmus. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2004;24(3):125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salzano FA, Guastini L, Mora R, Dellepiane M, Salzano G, Santomauro V, Salami A. Nasal tactile sensitivity in elderly. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130(12):1389–1393. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2010.495135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dell’Aversana Orabona G, Salzano G, Abbate V, Piombino P, Astarita F, Iaconetta G, Califano L. Use of the SMAS flap for reconstruction of the parotid lodge. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2015;35(6):406–411. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dell’Aversana Orabona G, Salzano G, Petrocelli M, Iaconetta G, Califano L. Reconstructive techniques of the parotid region. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(3):998–1002. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000000664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dell’Aversana Orabona G, Abbate V, Piombino P, Romano A, Schonauer F, Iaconetta G, Salzano G, Farina F, Califano L. Warthin’s tumour: Aetiopathogenesis dilemma, ten years of our experience. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015;43(4):427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turri-Zanoni M, Salzano G, Lambertoni A, Giovannardi M, Karligkiotis A, Battaglia P, Castelnuovo P. Prognostic value of pretreatment peripheral blood markers in paranasal sinus cancer: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio. Head Neck. 2017;39(4):730–736. doi: 10.1002/hed.24681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dix MR, Hallpike CS. The pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of the vestibular system. Ann Otol. 1952;61:987–1016. doi: 10.1177/000348945206100403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitzgerald G, Hallpike CS. Studies in human vestibular function: 1. Observation on the directional preponderance of caloric nystagmus resulting from cerebral lesions. Brain. 1942;65:115–137. doi: 10.1093/brain/65.2.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su GN, Tai PW, Su PT, Chien HH. Protracted benign paroxysmal positional vertigo following osteotome sinus floor elevation: a case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2008;23:955–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vernamonte S, Mauro V, Vernamonte S, Messina AM. An unusual complication of osteotome sinus floor elevation: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40:216–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sammartino G, Mariniello M, Scaravilli MS. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo following closed sinus floor elevation procedure: mallet osteotomes vs. screwable osteotomes. A triple blind randomized controlled trial. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2011;22:669–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.01998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vannucchi P, Giannoni B, Pagnini P. Treatment of horizontal semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Vestib Res. 1997;7:16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]