Abstract

Background

To systematically review the reconstructive options for oral submucous fibrosis utilizing buccal pad of fat versus conventional nasolabial and extended nasolabial flap versus platysma myocutaneous flap.

Objective

The succeeding systematic review and meta-analysis addresses the following question, what is the optimal reconstructive option for oral submucous fibrosis?

Study Design

A systematic electronic and manual database search revealed five relevant articles comparing buccal fat pad, nasolabial flap and platysma myocutaneous flap as reconstructive options in oral submucous fibrosis.

Methods

A total of 1538 articles were found across PubMed, Cochrane and clinical trials.gov. Only five relevant articles were selected for the study. Quality assessment of the selected studies was executed by Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Statistical software RevMan (Review Manager [Computer program], version 5.3, Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) was used for meta-analysis. Differences in means and risk ratios were used as principal summary measures. The overall estimated effect was categorized as significant where p < 0.05.

Results

Three of the five studies selected favoured buccal fat pad over nasolabial flap owing to its ease of harvest and lesser number of post-operative complications. One study favoured nasolabial flap because of the progressive increase in mouth opening and bulk of the tissue obtained for reconstruction. A single study favoured platysma flap over nasolabial flap although no difference was obtained in mouth opening, owing its excellent tissue bulk, fewer complications compared to the nasolabial flap.

Conclusion

Definitive conclusions cannot be drawn as there are number of limitations in the studies included. However, a general consensus has been towards favouring buccal fat pad over nasolabial flap. The platysma flap owing to its excellent tissue bulk and fewer complications can be considered as an alternative when dealing with defects which are challenging to reconstruct with the buccal fat pad.

Keywords: Oral submucous fibrosis, Nasolabial flap, Extended nasolabial flap, Buccal pad of fat, Platysma myocutaneous flap, Systematic review oral submucous fibrosis

Introduction

Rationale

According to Pindborg and Sirsat [1], oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) is a chronic sinister disease that affects the entire oral cavity, sometimes even pharynx and larynx. Symptoms include blanching and stiffness of the oral mucosa, instigating a progressive limitation in mouth opening and intolerance to hot and spicy food. OSMF is a debilitating, pre-cancerous condition, commonly seen in Asian countries, with high prevalence in Indian population and being strongly associated with areca nut chewing [2, 3]. The treatment for this condition requires the release of fibrous bands to increase mouth opening. In the early stages of the disease, medical therapy is beneficial and includes injection with steroids and hyaluronidase, antioxidants, vitamins and iron supplements and placental extracts. For advanced stages of OSMF, surgery is the only option available which involves resection of the fibrotic bands and reconstruction of the defect using various techniques [4].

Various surgical treatment modalities have evolved, but the mainstay is release of fibrosis by excision of fibrous bands with or without grafts [5]. A variety of reconstructive options are available including islanded palatal mucoperiosteal flap, tongue flap, buccal pad of fat, radial forearm flap, temporalis myofascial flap, placental grafts, skin grafts, lingual pedicle flaps, the temporalis fascia flap with split thickness skin graft, flaps from anterolateral thigh, artificial dermis and nasolabial flaps [6–14]. In severe trismus cases, bilateral coronoidectomy and temporalis myotomy can be performed to relieve the trismus and enhance the mouth opening [15].

Objectives

A systematic literature review of buccal fat pad, nasolabial flap and platysma myocutaneous flap as reconstructive options in patients with oral submucous fibrosis.

To outline the effectiveness of each flap, their limitation in patients with OSMF.

Methods

The current systematic review has been prepared according to the equator guidelines (https://www.equator-network.org) and Prisma Statement (http://prisma-statement.org/).

Electronic and manual literature searches were carried out for studies relating various reconstructive options for OSMF published until August 2019. The results were limited to studies written in English. The terms which were imported in the search strategy on various databases (PubMed, Cochrane and clinicaltrials.gov) were oral submucous fibrosis, buccal pad of fat, nasolabial, extended nasolabial flap and platysma myocutaneous flap. (“oral submucous fibrosis”[MeSH Terms] OR (“oral”[All Fields] AND “submucous”[All Fields] AND “fibrosis”[All Fields]) OR “oral submucous fibrosis”[All Fields]) AND buccal[All Fields] AND (“Pathog Dis”[Journal] OR “pad”[All Fields]) AND fat[All Fields] AND nasolabial[All Fields] AND extended[All Fields] AND (“surgical flaps”[MeSH Terms] OR (“surgical”[All Fields] AND “flaps”[All Fields]) OR “surgical flaps”[All Fields] OR “flap”[All Fields]) AND (“superficial musculoaponeurotic system”[MeSH Terms] OR (“superficial”[All Fields] AND “musculoaponeurotic”[All Fields] AND “system”[All Fields]) OR “superficial musculoaponeurotic system”[All Fields] OR “platysma”[All Fields]) AND (“myocutaneous flap”[MeSH Terms] OR (“myocutaneous”[All Fields] AND “flap”[All Fields]).

Inclusion criteria:

Comparative human randomized and non-randomized controlled trials; prospective and retrospective cohort studies that comprised of options for oral submucous fibrosis; buccal pad of fat versus nasolabial and extended nasolabial flap versus platysma myocutaneous flap.

Studies comparing at least two of the above-mentioned reconstructive options

The studies included should be based on data obtained from patients who had mouth opening of less than 25 mm, painful ulcerations, burning sensation, intolerance to spices, a habit of betel nut or tobacco chewing.

Studies with an average follow-up for 6 months

Exclusion criteria:

Non comparative studies including buccal fat pad, nasolabial flap and platysma myocutaneous flap.

Case reports and case series.

Studies evaluating the effect of other reconstructive options like skin grafts, temporal fascia, free flaps, etc.

Study Selection

Two reviewers screened all identifiable titles and abstracts independently. In addition, the reference lists of the subsequently selected abstracts and the bibliographies of the systematic reviews, human randomized and non-randomized controlled trials and; prospective and retrospective cohort studies were searched manually. For studies appearing to meet the inclusion criteria, or for which insufficient data in the title and abstract was available, the full text was obtained. Disagreements were solved through discussion between the reviewers. Finally, the full-text evaluation of the remaining publications was done using the above-listed inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction and meta-analysis: Two reviewers independently extracted data from the included studies. Disagreements were again resolved through discussion. Corresponding authors were contacted when data were incomplete or unclear. With respect to the listed question of our systematic review, data were sought for predictor variables i.e. buccal pad of fat, nasolabial, extended nasolabial flap and platysma myocutaneous flap. Both reviewers evaluated the primary outcome variable, which was post-operative mouth opening. The secondary outcome variables were the presence of extraoral scar, widening of the oral commissure, complications related to the flap itself including flap necrosis, donor site paraesthesia, etc. Meta-analysis was attempted for studies reporting the same outcome measures. Finally, funding sources of the selected studies have been checked.

Quality of the Studies

Quality assessment of the selected studies was executed by Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Scale was applied for cohort studies to judge each included study on selection of studies, comparability of cohorts and the ascertainment of either the exposure or outcome of interest. Stars were awarded such that the highest quality studies were awarded up to nine stars.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical software RevMan (Review Manager [Computer program], version 5.3, Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) was used for meta-analysis. Differences in means and risk ratios were used as principal summary measures. The overall estimated effect was categorized as significant where p < 0.05.

Results

A systematic review of the literature search revealed five relevant articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria; comparing the effectiveness of buccal fat pad, nasolabial flap and platysma myocutaneous flap as reconstructive options in OSMF. These studies were used for data extraction and meta-analysis.

Study Characteristics

Within the remaining group of five included studies, one was retrospective study; three were prospective comparative studies and one clinical trial. All studies considered for meta-analysis were comparative studies. Studies by Pardeshi et al. [3] and Rai et al. [16] compared the buccal pad of fat with nasolabial flap; whereas study by Patil et al. [5] and Agrawal et al. [4] compared the buccal pad of fat with extended nasolabial flap. The study by Bande et al. [17] compared extended nasolabial flap with the platysma myocutaneous muscle flap. The predictor variable for all the studies was a reduced mouth opening, < 15 mm (Pardeshi et al. [3], Patil et al. [5]), < 20 mm (Rai et al. [16]) and < 25 mm (Agrawal et al. [4], Bande et al. [17]) (Table 1); painful ulcerations, burning sensation, intolerance to spices, a habit of betel nut or tobacco chewing, and who were histologically confirmed cases of OSMF. All studies determined the effect of treatment variables by assessing the results after following patients post-operatively for various time periods, up to 6 months (Agrawal et al. [4]), 1 year (Pardeshi et al., Patil et al., Rai et al.) and 3 years (Bande et al.).

Table 1.

Mean of mouth opening (in mm)

| Groups | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| BFP group | 24.75 | 30.47 | 28.0733 | 2.97046 | 20.6943 | 35.4524 |

| NL group | 30.00 | 32.00 | 31.00 | 1.41 | 25.1469 | 37.8531 |

| ENL group | 21.50 | 40.00 | 29.52 | 8.38 | 16.1889 | 42.8661 |

| Platysma group | 40.00 | 41.00 | 40.50 | 0.707 | 34.1469 | 46.8531 |

| One-way ANOVA of your kk = 4 independent treatments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Sum of squares SS | Degrees of freedom df | Mean square MS | F statistic | p-value |

| Treatment | 212.7865 | 3 | 70.9288 | 2.1639 | 0.1804* |

| Error | 229.4523 | 7 | 32.7789 | ||

| Total | 442.2389 | 10 | |||

*p-value > 0.05 is statistically insignificant

Results of the Individual Studies

As measured in the five included studies, four studies used buccal pad of fat for management with total number of patients 60, and post-operatively mean mouth opening was 28.07 mm, ranged from 24.75 to 30.47 mm (95% CI 20.69–35.45). In two studies, nasolabial flap was used for surgical management in 35 patients and mean mouth opening found post-operatively was 32 mm (95% CI 25.14–37.85). In three studies, 25 patients were analysed for extended nasolabial flap with mean post-operative mouth opening of 29.52 mm, ranging from 21.5 to 40 mm (95% CI 16.18–42.86). In one retrospective study, author analysed use of platysma in 10 patients with mean mouth opening of 41 mm post-operatively (95% CI 34.14–46.85).

Quality of the Studies

Quality assessment of the included clinical trials, retrospective and prospective cohort studies was executed according to the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. All the five studies were of moderate quality, and risk of bias is present in all. For the retrospective study, the total data obtained were dependent on previous records. As the variability is noticed in the criteria of mouth opening and the absence of a larger sample size in all the studies could ascertain the results as concluded from them. The studies highlight the clinical applications of the different treatment options available for OSMF. In our validity assessment, we found that the Bande et al. paper is at high risk of bias, as it estimated the retrospective data for the outcome of treatment of OSMF. The study of Patil et al. is also not conclusive as sample size taken for estimation of result was too small.

Synthesis of Results

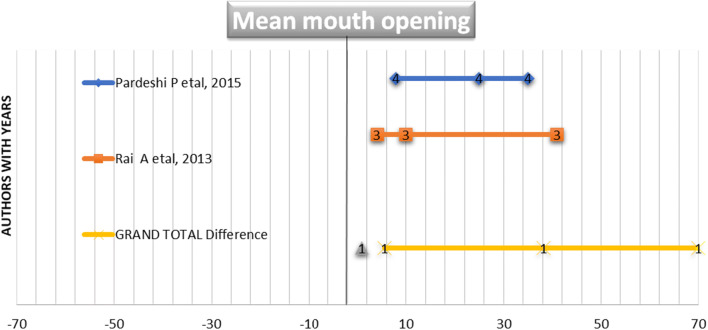

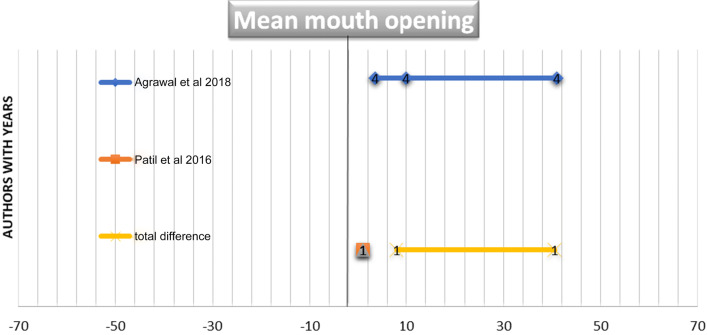

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate a forest plot graphs showing a significant association between post-operative mouth openings in all the referred studies. The mean mouth opening of two included studies using BPF and NL flap including 70 patients is 38.25 ± 5.6. The forest plot in Fig. 1 demonstrates a significant correlation between BPL and NL groups in both the included studies. The mean mouth opening of two included studies using BPF and ENL flap including 40 patients is 32.3 ± 6.89. The forest plot in Fig. 2 demonstrates a significant correlation between BPL and ENL groups in both the included studies. The mean mouth opening of one included study using platysma and NL flap including 20 patients is 40.05 ± 7.89 and demonstrated a significant correlation between platysma and NL groups in the included study.

Fig. 1.

Forest plot graph was plotted to draw inference from two related articles used for systematic review. The articles were named by authors with years. The parameters plotted in graph are N, mean and standard deviation of mouth opening in BPL and NL cases

Fig. 2.

Forest plot graph was plotted to draw inference from two related articles used for systematic review. The articles were named by authors with years. The parameters plotted in graph are N, mean and standard deviation of mouth opening in BPL and ENL cases

Discussion

The study by Agrawal et al. followed patients at regular interval for a period of 6 months and found statistically significant difference between pre-operative and post-operative mouth opening in both the groups. Over the period of next 6 months, there was a progressive improvement in mouth opening in patients reconstructed with nasolabial flap compared to the buccal fat pad. The buccal fat pad group although had a sudden increase in mouth opening intraoperatively and over a period of next 2 weeks, showed a decline in mouth opening at 6 months. The study favoured nasolabial flap for reconstructive purpose owing to the steady increment in mouth opening. However, there was no significant difference in mouth opening among both the groups over a period of 6 months. The study highlighted the drawback of buccal fat pad in closing the anterior most portion of the defect and the nasolabial flap in terms of intraoral hair growth and an extraoral scar. Nevertheless, a short duration of follow-up and a small sample size were the major limitations of the study. Similar results were obtained by studies of Kavarana et al. [18] and Borle et al. [19]. Yeh et al. [20], in his study, discussed the drawbacks of buccal fat pad in OSMF. The anterior reach of the flap is often not adequate leaving behind a raw are which heals by secondary intention leading to atrophy.

The study by Bande et al. compared extended nasolabial flap versus platysma myocutaneous flap with coronoidectomy in patients with OSMF. They favoured the platysma flap over the nasolabial flap as all the patients of the latter group had extraoral scars compared with none of the platysma flap group. Considering delayed complications, there were none in the platysma group. However, two patients of the nasolabial group had fish mouth deformity even after a year.

In his 2018 prospective study, Bande et al. [21] appraised the effectiveness of platysma myocutaneous flap in oral cavity reconstruction of patients with OSMF and early stage (T1N0M0) oral cavity carcinomas. They concluded that platysma flap is a good versatile flap for small to medium-sized intraoral defects ranging from 2 to 4 cm2. Uneventful healing, minimal donor site morbidity, acceptable donor site scarring, negligible intraoral hair growth, excellent colour match and flap thickness were some of the advantages of the flap. The platysma flap is based on perforators from the submental branch of the facial artery which has numerous anastomosis with ipsilateral and contralateral lingual, inferior labial and superior thyroid arteries. Although it is desirable to preserve the facial artery, the survival of the flap is not compromised even when it is ligated. The size of the skin paddle can vary from 5–10 to 7–14 cm [22]. Coleman et al. [23] recommended using a skin paddle of 5 cm to preserve maximum number of perforators as smaller-sized skin paddles can compromise vascular supply to the flap [24].

The randomised controlled trial by Pardeshi et al. compared the usefulness of nasolabial flap versus buccal fat pad for OSMF. They concluded that buccal fat pad was effective in moderate cases of trismus (> 15 mm mouth opening), whereas nasolabial flap is effective in severe trismus (< 15 mm mouth opening), as it provides the bulk required for reconstruction. Similar results were also obtained by studies of Gupta and Sharma [25] and Tideman et al. [26].

Patil et al. compared extended nasolabial flap versus buccal fat pad in their prospective pilot study. Although nasolabial flaps provided the bulk required for closure, it had several disadvantages as compared to buccal fat pad. This study contradicted the study done by Agrawal et al. The study by Patil et al. favoured buccal fat pad as a reconstructive option owing to the increase in mouth opening at the end of 1 year. The study highlighted the drawbacks of the nasolabial group; intraoral hair growth, extraoral scar, temporary widening of the commissures. The study also tinted on the fact that; nasolabial flaps are suitable for larger defects particularly juxtaposed defects of the buccal mucosa. The buccal fat pad is particularly useful in moderate-sized defects as the anterior reach of the flap is questionable in larger defects.

The pilot study by Rai et al. also favoured buccal fat pad over nasolabial flap owing to fewer complications in the former group. Both the groups had certain similar complications like subluxation of the TMJ and fish mouth deformity; however, the nasolabial group had significant aesthetic challenges. The study also highlighted that atrophy of the buccal fat pad leading to reduction in mouth opening can be controlled by aggressive physiotherapy, which is a limitation of buccal fat pad. Increase in the intercommisural distance is a significant drawback of the nasolabial flap as highlighted by this study. The study also proposed a protocol for management of OSMF: (1) Cessation of betel nut and tobacco chewing habits. (2) Fibrotomy. (3) Bilateral coronoidectomy/coronoidotomy. (4) Extraction of all third molar teeth. (5) Reconstruction with nasolabial flap or buccal fat pad. (6) Aggressive physiotherapy and regular follow-up.

Mehrotra et al. [27] in her retrospective review of 100 patients compared several reconstructive options for OSMF; buccal fat pad, nasolabial flap, tongue flap and split thickness skin graft. The results were not statistically significant with regards to interincisal distance; however, there was a gradual fall in mouth opening amongst all the groups. The nasolabial group sustained the 1-week post-operative mouth opening to the maximum over the follow-up period. They study favoured buccal fat pad over other reconstructive options, owing to its ease of harvest and reduced post-operative morbidity. The study also outlined a treatment strategy according to the clinical grading, considering surgery only in advanced cases with supportive medical therapy.

Aafiya et al. [28] proposed a sandwich technique to treat OSMF, a combination of nasolabial flap and buccal fat pad. The rationale was that the anterior reach of the buccal fat pad is questionable and as such it is left to heal by secondary intention causing atrophy, whereas nasolabial flap is associated with post-operative aesthetic challenges and also sometimes the posterior limit of the flap in the oral cavity is not adequate leaving behind a dead space. In this technique, the buccal fat pad is used to reconstruct the posterior most part of the oral cavity defect annulling any dead space, and the nasolabial flap is used to reconstruct the anterior part.

Limitations

The current systematic review studied the literature on treatment options available for OSMF. The five included papers were analysed separately. As demonstrated by equality of the risk ratios and on account of the limited amount of included studies, the relevance of obtained information needs to be verified further. Bias is present in the included papers, and this can have a substantial impact on our findings.

Except for one study, rest all the studies are either prospective or retrospective studies. There is variation in follow-up amongst all the studies. Contradicting conclusions have been drawn with regards to three of our included studies; Agrawal et al. favoured nasolabial flap over buccal fat pad, as there is a progressive increase in mouth opening. Studies by Patil et al. and Rai et al. favoured buccal fat pad over nasolabial owing to a steady decline in mouth opening among the nasolabial group and also the increasing complication rates in the latter. There is also variation in the pre-operative mouth opening amongst the groups; nevertheless, a mouth opening of < 15 mm has been considered to be of severe trismus.

Conclusion

With all the literature research within the scope of our systematic review, definitive conclusion cannot be drawn regarding the best reconstructive option for OSMF. Nevertheless, majority of the studies favoured buccal fat pad over nasolabial flap. The major limitation of the buccal fat pad is the anterior reach of the flap leading to atrophy on long-term basis. However, studies have shown that aggressive physiotherapy annuls this effect. The nasolabial flap along with its increase in post-operative morbidity leaves a dead space posteriorly in the oral cavity. A sandwich technique seems to be effective in this regard. The platysma flap is a very versatile flap for oral cavity reconstruction with reduced post-operative morbidity as compared to the nasolabial flap and increased tissue bulk as compared to the buccal fat pad. Hence, a greater number of clinical trials and observational studies are required before drawing definitive conclusions regarding the best reconstructive option for OSMF.

Author Contributions

PT, RNB, NC: Conception and design of study/review/case series, acquisition of data: laboratory or clinical/literature search, analysis and interpretation of data collected, drafting of article and/or critical revision. Final approval and guarantor of manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or no profit sectors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Preeti Tiwari, Email: drtiwaripreeti@gmail.com.

Rathindra Nath Bera, Email: rathin12111991@gmail.com.

Nishtha Chauhan, Email: chauhannishtha@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Pindborg JJ, Sirsat SM. Oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;22(6):764–779. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(66)90367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang X, Hu J. Drug treatment of oral submucous fibrosis: a review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(7):1510–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardeshi P, Padhye M, Mandlik G, Mehta P, Vij K, Madiwale G, et al. Clinical evaluation of nasolabial flap and buccal fat pad graft for surgical treatment of oral submucous fibrosis—a randomized clinical trial on 50 patients in Indian population. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(Supp 1):e121–e122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2015.08.733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agrawal D, Pathak R, Newaskar V, Idrees F, Waskle R. A comparative clinical evaluation of the buccal fat pad and extended nasolabial flap in the reconstruction of the surgical defect in oral submucous fibrosis patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;76(3):676.e1–676.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patil SB, Durairaj D, Suresh Kumar G, Karthikeyan D, Pradeep D. Comparison of extended nasolabial flap versus buccal fat pad graft in the surgical management of oral submucous fibrosis: a prospective pilot study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2017;16(3):312–321. doi: 10.1007/s12663-016-0975-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yen DJC. Surgical treatment of submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;54(3):269–272. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murti PR, Bhonsle RB, Pindborg JJ, Daftary DK, Gupta PC, Mehta FS. Malignant transformation rate in oral submucous fibrosis over a 17-year period. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1985;13(6):340–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1985.tb00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egyedi P. Utilization of the buccal fat pad for closure oroantral and/or oro-nasal communications. J Maxillofac Surg. 1977;5(4):241–244. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0503(77)80117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mokal NJ, Raje RS, Ranade SV, Prasad JS, Thatte RL. Release of oral submucous fibrosis and reconstruction using superficial temporal fascia flap and split skin graft—a new technique. Br J Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;58(8):1055–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamath VV. Surgical interventions in oral submucous fibrosis: a systematic analysis of the literature. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14(3):521–531. doi: 10.1007/s12663-014-0639-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JT, Cheng LF, Chen PR, Wang CH, Hsu H, Chien SH, Wei FC. Bipaddled radial forearm flap for the reconstruction of bilateral buccal defects in oral submucous fibrosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36(7):615–619. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsao CK, Wei FC, Chang YM, Cheng MH, Chwei-Chin Chuang D, Kao HK, Dayan JH. Reconstruction of the buccal mucosa following release for submucous fibrosis using two radial forearm flaps from a single donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(7):1117–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang JJ, Wallace C, Lin JY, Tsao CK, Kao HK, Huang WC, Cheng MH, Wei FC. Two small flaps from one anterolateral thigh donor site for bilateral buccal mucosa reconstruction after release of submucous fibrosis and/or contracture. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(3):440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko EC, Shen YH, Yang CF, Huang IY, Shieh TY, Chen CM. Artificial dermis as the substitute for split-thickness skin graft in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20(2):443–445. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31819b97d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang YM, Tsai CY, Kildal M, Wei FC. Importance of coronoidotomy and masticatory muscle myotomy in surgical release of trismus caused by submucous fibrosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(7):1949–1954. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000122206.03592.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rai A, Datarkar A, Rai M. Is buccal fat pad a better option than nasolabial flap for reconstruction of intraoral defects after surgical release of fibrous bands in patients with oral submucous fibrosis? A pilot study: a protocol for the management of oral submucous fibrosis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42(5):e111–e116. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bande CR, Datarkar A, Khare N. Extended nasolabial flap compared with the platysma myocutaneous muscle flap for reconstruction of intraoral defects after release of oral submucous fibrosis: a comparative study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51(1):37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kavarana NM, Bhathena HM. Surgery for severe trismus in submucous fibrosis. Br J Plast Surg. 1987;40(4):407–409. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(87)90045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borle RM, Borle SR. Management of oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49(8):788–791. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh CJ. Application of buccal fat pad to the surgical treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;25(2):130–133. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(96)80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bande C, Joshi A, Gawande M, Tiwari M, Rode V. Utility of superiorly based platysma myocutaneous flap for reconstruction of intraoral surgical defects: our experience. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;22(1):45–51. doi: 10.1007/s10006-017-0665-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Futrell JW, Johns ME, Edgerton MT, Cantrell RW, Fitz-Hugh GS. Platysma myocutaneous flap for intraoral reconstruction. Am J Surg. 1978;136(4):504–507. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coleman JJ, Jurkiewicz MJ, Nahai F, Mathes SJ. The platysma musculocutaneous flap: experience with 24 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;72(3):315–321. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198309000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howaldt HP, Bitter K. The myocutaneous platysma flap for the reconstruction of intraoral defects after radical tumour resection. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1989;17(5):237–240. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(89)80076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta D, Sharma SC. Oral submucous fibrosisda new treatment regimen. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46(10):830–833. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tideman H, Bosanquet A, Scott J. Use of the buccal fat pad as pedicled graft. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;44(6):435–440. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(86)80007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehrotra D, Pradhan R, Gupta S. Retrospective comparison of surgical treatment modalities in 100 patients with oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(3):e1–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ambereen A, Lal B, Agarwal B, Yadav R, Roychoudhury A. Sandwich technique for the surgical management of oral submucous fibrosis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;57(9):944–945. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2019.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]