Abstract

Aim

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) ankylosis is an extremely disabling affliction that causes problems in mastication, digestion, speech, appearance and hygiene. Surgery of TMJ ankylosis needs careful evaluation and planning to yield predictable results. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis is very common among young children. The aim of treatment is not only to treat the movement of the joint but also to prevent relapse.

Materials and Method

In this series, 18 cases of temporomandibular joint ankylosis were treated at our institute from January 2012 to January 2017 with osteoarthrectomy and interpositional arthroplasty. Patients were in the age range of 5–57 years, with 11 males and 7 females and including 8 unilateral and 10 bilateral cases. Duration of ankylosis ranged from less than 2 years to more than 6 years. Seven of the patients were secondarily taken up for correction of their deformities with either orthognathic surgery or distraction osteogenesis.

Results

Good mouth opening was achieved in all the patients with a mean follow-up period of 12 months. The early post-operative mouth opening ranged from 24 to 37 mm. The late post-operative mouth opening ranged from 20 to 33 mm. There was a stress on aggressive physiotherapy for a minimum of 6 months in all our patients.

Conclusion

Interpositional arthroplasty using vascularized temporalis fascia flap is a very reliable method to prevent recurrence of ankylosis, and it also avoids the disadvantages of alloplastic materials as well as nonvascularized autogenous tissues.

Keywords: Temporomandibular joint ankylosis, Temporalis fascia flap, Interpositional arthroplasty

Introduction

Temporomandibular joint ankylosis (TMA) is a highly distressing condition in which the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is replaced by scar tissue. The TMA can be classified using a combination of location (intraarticular or extra-articular) [1], type of tissue involved (bone, fibrous or fibro-osseous) [2] and extent of fusion (complete or incomplete). TMA partially or totally prevents the patient from opening his or her mouth. This disabling condition causes speech impairment, difficulty with mastication, poor oral hygiene and abnormalities of facial growth, generating significant psychological stress. TMA is most frequently associated with trauma, but local or systemic infection, tumours, degenerative diseases, intraarticular injection of corticosteroid, forceps delivery and complication of previous TMJ surgery have also been implicated. The common causes are trauma and infection. Younger patients have a greater tendency towards post-traumatic ankylosis, mostly before 10 years of age [3].

A number of surgical approaches have been designed to restore normal joint functioning and prevent reankylosis. The basic techniques are used: (a) gap arthroplasty, where a resection of bone between the articular cavity and mandibular ramus is created without any interposition material; (b) interpositional arthroplasty, which adds interpositional material between the new sculptured glenoid fossa and condyle; (c) joint reconstruction, when the TMJ is reconstructed with an autogenous bone graft or total joint prosthesis [4]; and (d) restoring the ramal condylar unit by distraction—neocondylogenesis.

Surgical intervention for correcting TMA may include autogenous costochondral rib grafts after condylectomy, mainly used for children due to the potential for continuous growth. Gap arthroplasty with tissue interposition between the mandibular ramus and glenoid fossa has been performed mainly in adults. Appropriate interposition materials include: (1) autogenous tissues: meniscus, muscle, fascia, skin, cartilage, fat or a combination of these tissues; (2) allogeneic tissues: cartilage and dura; (3) alloplastic: silastic materials, acrylic, Proplast and silicone; and (4) xenograft tissues: usually of bovine origin (collagen and cartilage). Gap arthroplasty without material interposition has also been performed. When preserved, the remaining TMJ disc, which has been displaced medially and anteroinferiorly, can be replaced and used as interpositional tissue for preventing reankylosis, in combination with the gap arthroplasty technique [5].

The aim of treatment in temporomandibular joint ankylosis is not only to re-establish the movement at the joint but also to prevent it from relapsing again. The restoration of occlusion and minimizing the secondary facial and occlusal abnormalities in children are equally important considerations, which may be achieved by interceptive surgery in an attempt to restore normal facial growth. In adults, however, due to the failure of adaptation of occlusion to the abnormal situation, corrective surgery to realign the chin point may leave a large lateral open bite on the affected side. Camouflaging procedures such as genioplasty may produce an acceptable result [6].

The most important aim, however, must be to restore normal function, which can be best achieved at the level of previous glenoid fossa from the mechanical point of view. This, however, is also the level at which reankylosis is most likely to occur [4].

Materials and Methods

With the approval of ethical committee of the institution, the study was conducted on 18 patients (11 males, 7 females) who presented with true TMJ ankylosis. Trauma was the cause of the ankylosis in most of the cases (13 cases), and 5 were of congenital origin. The patients’ age ranged from 5 to 57 years. Ankylosis was bilateral in 10 cases and unilateral in 8 cases. None of the patients had been previously operated for ankylosis release.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. A thorough history was taken. Age, sex, aetiology, side of involvement, duration of symptoms, and the mouth opening were recorded before the operation. All the patients were evaluated using physical and radiological examinations (three-dimensional, axial and coronal CT scans and panoramic radiographs were obtained), the degree of mouth opening was evaluated pre-op, during surgery, early post-op (during the time of discharge) and late post-operatively (at the last visit which ranged from 6 months to 2 years after surgery), and the mouth opening was considered to be the maximum interincisal distance.

The average duration of the condition from trauma or birth depending on the aetiology was 4 years. Thirteen of the 18 patients also presented with a residual deformity in the form of hypoplastic mandible or facial asymmetry.

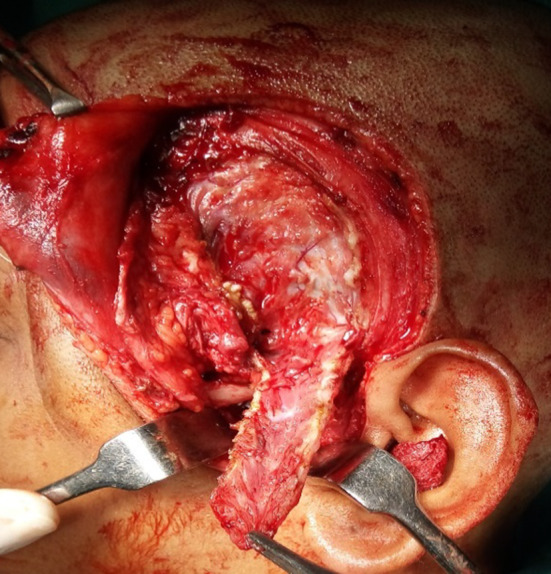

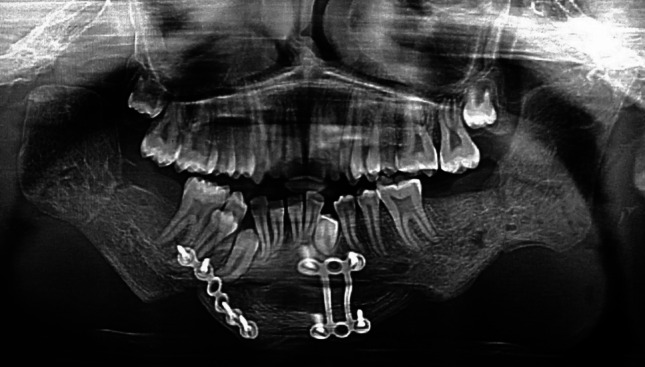

The surgical procedure included general anaesthesia through fibre-optic bronchoscope-assisted nasoendotracheal intubation. The classic Alkayat Bramley preauricular approach was used (Fig. 1) to obtain access to the region. After determining the anterior and posterior limits of the ankylosed condyle (Fig. 2), the bony segment was resected using microsaws to separate the ramus from the cranial base, thus creating gap of approximately 1 cm (Fig. 3). The irregular edges of the segments were smoothened by bur, and the ramus was completely disconnected from the upper bony block. Coronoidectomy was performed only ipsilaterally in 4 patients through the same approach, while bilateral coronoidectomy was done in 14 cases. Four of these cases were unilateral ankylosis cases requiring the contralateral coronoidectomy through an intraoral approach to achieve adequate mouth opening. The pedicled temporalis fascia was harvested (Fig. 4) rotated over the zygomatic arch and sutured medial to the gap created to the medial pterygoid muscle. Suction drain was placed in all the cases and pressure dressing applied over the surgical site. Early mobilization to prevent hypomobility was encouraged. Jaw-opening exercise, active chewing movements and intensive physiotherapy were started within 7 days of surgery, and patients and their relatives were advised to continue the same for 6 more months. During the follow-up period, the patients were evaluated clinically and by panoramic radiographs (Fig. 5).

Fig. 1.

Alkayat Bramley incision

Fig. 2.

Right TMJ ankylosis

Fig. 3.

Osteoarthrectomy

Fig. 4.

Preparing the temporal fascial flap

Fig. 5.

After release of ankylosis

Results

The surgical protocol adopted in the 18 patients was osteoarthrectomy along with interpositional temporalis musculofascial flap along with ipsilateral coronoidectomy. Contralateral coronoidectomy of the uninvolved side was performed in 4 patients. The approach to the ankylosis was Alkayat Bramley approach in all cases. The early post-operative mouth opening ranged from 24 to 37 mm.

A minimum of 6-month vigorous physiotherapy was recommended in all patients. On review, over a period of 6 months to 2 years, the late post-operative mouth opening ranged from 20 to 33 mm.

There were no complications in the late post-operative periods. Temporal facial palsy that lasted 3 weeks post-operatively was observed in 11 cases. At the end of 3 months, this resolved spontaneously. All the patients had satisfactory mouth opening and occlusion. Most of the bilateral cases had an anterior open bite in the initial phase due to the sudden loss of the masticatory muscle influence. Jaw exercises and training of the muscles in the post-operative phase resulted in settling of this occlusal discrepancy in 6 months time.

Properties and results of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The summary of the patient characteristics

| Patient | Age | sex | Aetiology | Affected side | Mouth opening (pre-op) (mm) | Mouth opening (early post-op) (mm) | Mouth opening (late post-op) (mm) | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23 | F | Trauma | B/L | 7 | 24 | 30 | Facial palsy/anterior open bite |

| 2 | 20 | M | Trauma | B/L | 5 | 36 | 29 | Anterior open bite |

| 3 | 5 | M | Trauma | B/L | 2 | 25 | 33 | Anterior open bite |

| 4 | 8 | M | Trauma | Unilateral | 5 | 28 | 31 | |

| 5 | 18 | M | Trauma | B/L | 4 | 24 | 25 | Facial palsy/anterior open bite |

| 6 | 21 | F | Trauma | B/L | 2 | 29 | 27 | Facial palsy/anterior open bite |

| 7 | 19 | M | Trauma | Unilateral | 10 | 36 | 28 | Facial palsy |

| 8 | 6 | M | Trauma | Unilateral | 6 | 33 | 33 | |

| 9 | 24 | M | Trauma | Unilateral | 10 | 32 | 28 | Facial palsy |

| 10 | 12 | M | Trauma | B/L | 3 | 25 | 24 | Facial palsy |

| 11 | 32 | F | Congenital | Unilateral | 2 | 33 | 26 | Facial palsy |

| 12 | 18 | F | Trauma | B/l | 4 | 24 | 22 | Anterior open bite |

| 13 | 4 | F | Congenital | B/L | 2 | 26 | 22 | |

| 14 | 57 | M | Trauma | Unilateral | 3 | 24 | 30 | Facial palsy |

| 15 | 10 | M | Congenital | Unilateral | 6 | 33 | 33 | Facial palsy |

| 16 | 21 | M | Congenital | B/L | 4 | 34 | 30 | Facial palsy/anterior open bite |

| 17 | 4 | F | Congenital | B/L | 3 | 25 | 20 | Anterior open bite |

| 18 | 16 | F | Trauma | Unilateral | 4 | 37 | 33 | Facial palsy |

Thirteen out of the 18 patients also had an obvious facial deformity. Only 7 of these agreed for further surgery to correct the condition. Four of these patients underwent body distraction in the sagittal plane along with advancement genioplasty to correct the deformity and achieve facial symmetry (Fig. 6). Three patients were subjected to bilateral sagittal split osteotomy for advancement of the hypoplastic mandible along with advancement genioplasty. All these procedures were undertaken after a minimum period of 6 months after release of ankylosis.

Fig. 6.

Radiograph after distraction and advancement genioplasty

Three of the 18 patients also had pre-operative signs and symptoms of obstructive sleep apnoea which included episodes of snoring, daytime sleepiness and fatigue. There was radiographic evidence of narrow oropharyngeal airway in lateral cephalograms. Due to financial constraints, polysomnography was not performed. All these patients had symptomatic relief with virtual absence of snoring and better sleep patterns at night after the release of the ankylosis and corrective surgery to treat the mandibular deficiency. In all these cases, release of the ankylosis preceded the mandibular advancement.

Discussion

The most important cause of TMJ ankylosis is trauma [7]. In intracapsular fractures, the condylar head splits in a sagittal plane and the lateral fragment passes upwards over the outer rim of the glenoid fossa. The associated disruption and displacement of the interarticular cartilaginous disc together with the inevitable loss of mobility may lead to ankylosis [4].

The normal mouth opening in adults ranges from 40 to 56 mm but varies in children depending upon the age and structure of the child. Ankylosis causes hypomobility of jaw movement and affects daily functions of speech, mastication and oral hygiene. In a growing child, it affects the development of the mandible, resulting in facial deformity, malocclusion and obstructive sleep apnoea–hypopnoea syndrome [4].

Treatment is surgical, and the various methods include simple resection of the bony fusion or resection plus interposition of alloplastic or autologous material. Another method is resection plus reconstruction of the condyle. Gap arthroplasty without interposition reported recurrence rate as high as 53% [7].

A 7-step protocol developed by Kaban, Perott and Fisher [8] for the treatment of TMJ ankylosis has been the mainstay of treatment for quite sometime. It includes (1) aggressive resection of the ankylotic segment, (2) ipsilateral coronoidectomy, (3) contralateral coronoidectomy when necessary, (4) lining of the joint with temporalis fascia or cartilage, (5) reconstruction of the ramus with a CCG, (6) rigid fixation of the graft and (7) early mobilization and aggressive physiotherapy. With this protocol, they achieved a mean maximum post-operative interincisal opening at 1 year of 37.5 mm, with lateral excursions present in 16 of 18 joints and pain present in 2 of 18 joints.

Rajgopal et al. have suggested radical condylectomy as well as coronoidectomy, but the vertical ramus height becomes greatly reduced [9]. Alloplastic materials like Proplast, Teflon, silastic, methyl methacrylate or autogenous tissue like fascia lata or muscle, full thickness skin or cartilage into the defect have also been tried [10].

Costal cartilage for the treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis gives good functional results, but antigen antibody reaction leading to late resorption of graft may lead to recurrence of ankylosis in the end. The grafted cartilage does evoke transplantation antigens, and the rejection response is merely delayed by the physical barrier that the matrix interposes between the chondrocytes and the cells of immune surveillance system of the recipient host. However, temporalis fascia flap is available at the operative site and is easy to raise and quick to execute. The vascularized flap shows less chance of subsequent absorption and fibrosis [10].

Abdul Hassan et al. have studied the surgical anatomy of temporal region. They found the superficial temporal fascia lies immediately deep to the hair follicles and is a part of the subcutaneous musculoaponeurotic system and is continuous in all direction with other structures belonging to that layer. We have used this temporalis fascia in all our patients and found that superficial temporal fascia has a rich blood supply and satisfactory arc of rotation to fill in the defect of osteotomy/ostectomy. The follow up of patients has shown no relapse and recurrence of ankylosis in the long run [11].

Total joint replacement for TMJ ankylosis has been restricted to end-stage arthritic disease, bony or fibrous ankylosis, failed autogenous tissue reconstruction or failed alloplastic reconstruction [12].

The secondary deformity of face results commonly from long-standing TMJ ankylosis of paediatric onset. The deformity has both cosmetic and functional effects. The cosmetic effects are borne by both mandible and maxillae. The resulting occlusion cant, restricted mandible growth and secondary maxillary undergrowth require both jaw surgeries. Simultaneous maxillomandibular distraction or conventional orthognathic surgery is indicated in these conditions. In case of functional effects on the posterior pharyngeal airspace, TMJ ankylosis may be associated with obstructive sleep apnoea, thus demanding management of both conditions. It is in these specific conditions that surgeons have advocated preceding ankylosis release with mandibular advancement by distraction [13].

Krishna Rao et al. have shown the role of simultaneous gap arthroplasty and distraction osteogenesis in the management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis in children, but this requires patient selection in whom semi-classical microstomia is coexisting [14].

Conclusion

The main aim of treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis is not only to achieve adequate mouth opening but also to prevent recurrence of ankylosis. Interposition arthroplasty using vascularized temporalis fascia flap is a very reliable method to prevent recurrence of ankylosis, and it also avoids the disadvantages of alloplastic materials as well as nonvascularized autogenous tissues. The success of the meticulous surgical reconstruction is dependent on good physiotherapy and with regular follow-up for at least one year.

Funding

None.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Satyapriya Shivakotee, Email: drsatyapriyashivakotee@gmail.com.

Col Suresh Menon, Email: psurmenon@gmail.com.

M. E. Sham, Email: ehtaisham@yahoo.com

Veerendra Kumar, Email: drveeru07@gmail.com.

S. Archana, Email: archana.dr.s@gmail.com

References

- 1.Kazanjian Varaztad H. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis with mandibular retrusion. Am J Surg. 1955;90(6):905–910. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(55)90721-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He D, Yang C, Chen M, Zhang X, Qiu Y, Yang X, Li L, Fang B. Traumatic temporomandibular joint ankylosis: our classification and treatment experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(6):1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bortoluzzi Marcelo Carlos, Sheffer MAR. Treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis with gap arthroplasty and temporal muscle/fascia graft: a case report with five-year follow-up. Rev Odonto Cienc. 2009;24(3):315–318. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guven O. A clinical study on temporomandibular joint ankylosis in children. J Cranio facial Surg. 2008;19(5):1263–1269. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181577b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karamese M, Duymaz A, Seyhan N, Keskin M, Tosun Z. Management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis with temporalis fascia flap and fat graft. J Cranio Maxillo Fac Surg. 2013;41:789–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodra P, Sundi A. Interposition arthroplasty using temporal fascia flap for temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Int J Contemp Med Res. 2017;4:2454–7379. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laskin DM. Role of the meniscus in the etiology of posttraumatic temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Int J Oral Surg. 1978;7:340. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(78)80106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaban LB, Perrott DH, Fisher K. A protocol for management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48(11):1145–1151. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90529-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajgopal A, Banerjee PK, Baluria V, Sural A. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis: a report of 15 cases. J Cranio Maxillofac Surg. 1983;11:37. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0503(83)80009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moriconi ES, Popowich LD, Guernsey LH. Alloplastic reconstruction of the temporomandibular joint. Dent Clin North Am. 1986;30(2):307–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abul-Hassan S, Hussain Grace Von, Dras Ascher AMI, Robert D, Acland MD. Surgical anatomy and blood supply of the fascial layers of the temporal region. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77:17–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mercuri LG. Temporomandibular joint total joint replacement: TMJ TJR—a comprehensive reference for researchers, material scientists and surgeons. New York: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrade NN, Kalra R, Shetye SP. New protocol to prevent TMJ reankylosis and potentially life threatening complications in triad patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:1495–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao K, Kumar S, Kumar V, Singh AK, Bhatnagar SK. The role of simultaneous gap arthroplasty and distraction osteogenesis in the management of temporo-mandibular joint ankylosis with mandibular deformity in children. J Cranio Maxillofac Surg. 2004;32:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]