Abstract

Background

Suicidal ideation and anxiety are common among adolescents although their prevalence has predominantly been studied in high income countries. This study estimated the population prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety and their correlates with peer support, parent-adolescent relationship, peer victimization, conflict, isolation and loneliness across a range of low-income, lower-middle-income, upper-middle-income countries and high-income countries (LMIC—HICs).

Methods

Data were drawn from the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) of adolescents aged 12–17 years between 2003 and 2015 in 82 LM-HICs from the six World Health Organization (WHO) regions. For those countries with repeated time point data in this study, we used data from the most recent survey. We estimated weighted prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety by country, region and at a global level with the following questions:-“Did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide during the past 12 months?” and “During the past 12 months, how often have you been so worried about something that you could not sleep at night?”. We used multiple binary logistic regression to estimate the adjusted association between adolescent age, sex, socioeconomic status, peer support, parent-adolescent relationship, peer victimization, conflict, isolation and loneliness with suicidal ideation and anxiety.

Findings

The sample comprised of 275,057 adolescents aged 12–17 years (mean age was 14.6 (SD 1.18) years of whom 51.8% were females). The overall 12 months pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety were 14.0% (95% CI 10.0–17.0%) and 9.0% (7.0–12.0%) respectively. The highest pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation was observed in the Africa Region (21.0%; 20.0–21.0%) and the lowest was in the Asia region (8.0%, 8.0–9.0%). For anxiety, the highest pooled prevalence was observed in Eastern Mediterranean Region (17.0%, 16.0–17.0%) the lowest was in the European Region (4.0%, 4.0–5.0%). Being female, older age, having a lower socioeconomic status and having no close friends were associated with a greater risk of suicidal ideation and anxiety. A higher levels of parental control was positively associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing suicidal ideation (OR: 1.65, 1.45–1.87) and anxiety (1.53, 1.30–1.80). Parental understanding and monitoring were negatively associated with mental health problems. Similarly, the odds of experiencing suicidal ideation and anxiety were higher among adolescents who had been experiencing peer conflict (1.36, 1.24–1.50; 1.54, 1.40–1.70), peer victimization (1.26, 1.15–1.38; 1.13, 1.02–1.26), peer isolation (1.69, 1.53–1.86; 1.76, 1.61–1.92) and reported loneliness (2.56, 2.33–2.82; 5.63, 5.21–6.08).

Interpretations

Suicidal ideation and anxiety are prevalent among adolescents although there is significant global variation. Parental and peer supports are protective factors against suicidal ideation and anxiety. Peer based interventions to enhance social connectedness and parent skills training to improve parent-child relationships may reduce suicidal ideation and anxiety. Research to inform the factors that influence country and regional level differences in adolescent mental health problems may inform preventative strategies.

Funding

None

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We systematically searched PubMed, EMBASE, PsycNIFO with a combination of MeSH heading terms and keywords. The key words used in the search (“suicide” OR “self-harm” OR “anxiety”) and (“adolescents” OR “child*” OR “teenager” OR “youth”) and (“developing country” OR “low socioeconomic status” OR “low income country” OR “middle income country” OR “low- and middle-income country” OR “ high income country” OR “low and middle income to high income countries” OR “LMIC—HICs” OR “LMICs”). The literature search was conducted up to August 27, 2019. We identified only one multicounty study which used data from the Global School-based Students Health Survey (GSHS) from 59 countries. We did not find any comparative study of the prevalence of suicidal ideation, anxiety among adolescents across low and middle to high income countries (LMIC—HICs). In addition, no prior study has evaluated the relationship between suicidal ideation and anxiety with peer support, parent-adolescent relationship, peer victimization, conflict, isolation and loneliness.

Added value of this study

This is the first study to comprehensively estimate the population prevalence of suicidal ideation, anxiety and its relationship with peer and parental support among adolescents across LMIC—HICs. We used data from the GSHS of adolescents, ages 12–17 years, in 82 LMIC—HICs in the six World Bank regions to show the geographic variation in prevalence of suicidal ideation, anxiety victimization in 82 LMIC—HICs. We demonstrated that parental involvement and peer support were strongly associated with reduced levels of suicidal ideation and anxiety.

Implications of all the available evidence

This study shows a large proportion of adolescents in all countries irrespective of income status experience suicidal thinking and anxiety although there is a high variation between countries. In every country, those adolescents with lower levels of peer and parental support and higher levels of parental control were more likely to report experiencing suicidal ideation and anxiety. Adolescent suicidal ideation and anxiety prevention strategies should address family and peer relationships which are socioculturally specific and sensitive.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Adolescents represent almost a quarter of the world's population [1] and are projected to proportionally increase in coming decades [2]. Adolescence is a pivotal developmental stage where improvements in health and education can establish an improved quality of lifetime health trajectories [3,4]. Nearly half of the global burden of disease has its origins in adolescence [5] and mental disorders account for 16% of the global burden of disease and injury in people aged 10–19 years [6,7]. In terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) mental and substance use disorders ranked 6th with 55.5 million DALYs and rise to 5th when mortality burden of suicide is attributed [6]. Data informing country and regional variation in prevalence estimates of mental health problems in adolescents are needed to identify potential modifiable risk factors and to inform differences in service needs globally.

Positive relationships with family and friends are consistently linked with improved mental health and wellbeing during adolescence [8], [9], [10]. For example, a study in Vietnam reported that greater parental understanding and monitoring was significantly associated with reduced risk of mental health problems. By contrast, greater parental control was significantly associated with greater likelihood of having suicidal ideation [11]. Similarly, positive peer support is important to the mental wellbeing of adolescents. Supportive peer relations following aversive peer experiences reduces the risk of internalizing and externalizing symptoms [12].

Globally 10–20% of adolescents have mental health problems and adolescents from low-resource settings are particularly vulnerable to mental ill-health [13]. A systematic review conducted in 27 countries including every world region reported that the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders was 13.4% (95% CIs 11.3–15.9) with the prevalence of any anxiety disorder reported as 6.5% (4.7–9.1) [14]. A recent study reported that more than three-quarters of suicides globally occur in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) [15]. However, in LMICs mental disorders still remain under-reported because of social stigma, religious or cultural taboos and inadequate reporting systems [16]. Some country-specific data are available, for example a study from Vietnam showed that more than 30% of adolescents self-reported life time experiences of low mood, and the prevalence rates of suicidal behaviours were 12.2% [17]. Another study in Pakistan reported that prevalence of anxiety and suicidal ideation were 8.4% and 7.3%, respectively. To date, there are a paucity of studies examining the prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety among adolescents in low- and middle-income country and comparing to high income country (LMIC—HIC) settings. Uddin et al. (2019) used the Global School-based student Health Survey (GSHS) data to examine suicidal ideation among adolescents in 59 LMICs without comparison with HICs. This study did not examine the correlates of suicidal ideation [15]. In the current study we aimed to estimate the prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety and examine their correlates among adolescents aged 12 to 17 years across 82 countries with varying income levels from different world regions.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

Data were from the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS), which commenced in 2003. The GSHS was jointly developed by the WHO and the United States centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in collaboration with The United Nations International Children's Fund (UNICEF), The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural organisation (UNESCO), and The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS). GSHS is administered to adolescents aged 12–17 years to capture information on a wide range of health indicators using validated items from ten core modules including: nutrition, physical activity, hygiene, mental health, alcohol use, tobacco use, drug use, sexual behaviors, violence/injury, and protective factors [18]. In collecting this information, GSHS employed a two-stage cluster sampling technique. In the first stage, the schools were selected randomly. Classes that provided a representative sample of the general population aged 12–17 years were selected within the schools at the second stage of sampling [19]. The study design and selection procedure of the participants were similar across the GSHS countries. For this study we included data from 82 LMIC—HICs from inception year 2003 to 2015. Only 10 countries had two-time point's data and that information presented in supplementary table-2. For those countries with repeated time point data in this study, we used data from the most recent survey.

2.1.1. Ethics statement

In each of the participating countries, the GSHS received ethics approval from the Ministry of Education or a relevant institutional ethics review committee, or both. Only those adolescents and their parents or guardians who provided written or verbal consent participated. As the current study used retrospective publicly available data, we did not require ethics approval.

2.2. Suicidal ideation and anxiety among adolescents

Suicidal ideation was examined with the question “Did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide during the past 12 months?” with a binary response of “yes” or “no.”

Anxiety was assessed with the question “During the past 12 months, how often have you been so worried about something that you could not sleep at night?” With response ‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’, ‘most of the time’ and ‘always’.

Anxiety responses were recoded and classified as ‘yes’, with endorsement of ‘most of the time/always’, and ‘no’, which included ‘never’, ‘rarely’, and ‘sometimes’.

2.3. Peer support

Peer support was assessed using a proxy variable based on the question “During the past 30 days, how often were most of the students in your school kind and helpful?” to which students could respond ‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’, ‘most of the time’ or ‘always’. Responses were recoded as never/rarely, sometimes, most of the times and always.

2.4. Parent–adolescent relationship

Parental understanding, parental monitoring and parental control are components of the relationship between the adolescent and their parents as perceived by the adolescent [20]. These were assessed with three questions: i) parental understanding of student's problems (“During the past 30 days, how often did your parents or guardians understand your problems and worries?”), ii) parental monitoring of student's activities during their free time (“During the past 30 days, how often did your parents or guardians really know what you were doing with your free time?”). iii) Parental control was examined with the question “How often did your parents or guardians go through your things without your approval during the past 30 days?” Possible response options to each of these questions were ‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’, ‘most of the time’ and ‘always’. These variables were recoded and classified as never/rarely, sometimes, most of the time and always.

2.5. Socio-demographic factors

The sex and age of the participants were included in the survey. Participants were categorized into three age groups: 12–13 years, 14–15 years and 16–17 years. Socioeconomic status (SES) was measured by the variable, “During the past 30 days, how often did you go hungry because there was not enough food in your home?” Responses of “never to rarely” were recoded as ‘average’, and “sometimes to always” as ‘below average’ SES [21]. We included country policy or plan for mental health as reported by the World Health Organization.

2.6. Peer victimization, conflict and loneliness

Conflict was assessed with two questions “During the past 12 months, how many times you were physically attacked” and “During the past 12 months, how many times were you in a physical fight?”. Student responses for conflict were recoded as ‘yes’ (reported being attacked or fighting one or more times) or ‘no’. Peer victimization was assessed with the question “How many days where you bullied during the past 30 days?” and the response was recoded as “yes” for answer of one or more days or “no”.

Loneliness was examined using the question “How often have you felt lonely during the past 12 months?” with responses ranging from “never” to “always.” The responses were dichotomized to “lonely” where the student endorsed “most of the time” or “always” or “no” meaning “never/rarely or sometimes”.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The data were weighted by primary sampling unit (PSU). The weighting is based on the PSU which is derived from the probability of a school being selected, a classroom being selected, school and student level non-response and gender. Therefore, the samples were nationally representative in respect to the study population. This included using strata and primary sampling units at the country level. Weighted mean estimates of prevalence (with corresponding 95% CIs) were calculated by country and sex. We used random-effects meta-analysis to generate regional and overall pooled estimates of suicide and anxiety data, using the DerSimonian and Laird inverse-variance method. Forest plots show the prevalence of each indicator by country and its corresponding weight, and the pooled prevalence by region and its associated 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity was examined using the I2-statistic and a high level of inconsistency (I2 > 50%) warranted the use of a random effect.

Bivariate analysis was performed to calculate the prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety over background characteristics at the global and regional level. We conducted binary logistic regression analysis to examine the associations between suicidal ideation and anxiety with peer support, parent-adolescent relationship, peer victimization, conflict, isolation and loneliness. We conducted multiple regression models which included all significant variables binary logistic regression and survey year to explore independent factors associated with suicidal ideation and anxiety. Variations due to clustering were controlled in all analyses.

3. Results

The sample comprised of 275,057 adolescents aged 12–17 years (mean age was 14.6 (SD 1.18) years of whom 51.8% were females. Response rates ranged from 60% in Chile to 99.8% in Jordan (supplementary Table 1). Of the 82 participating countries by World Bank classification, 25.0% of the data came from low-income countries, 31.5% from lower-middle-income countries, and 20.1% from upper-middle-income countries and 23.4% from high-income countries.

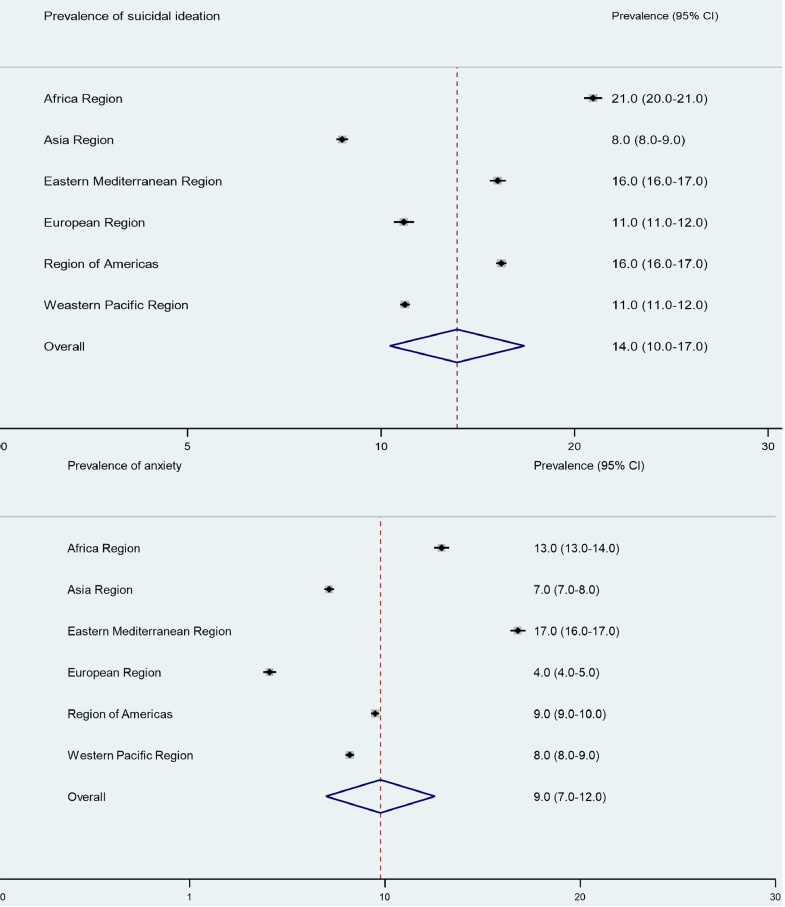

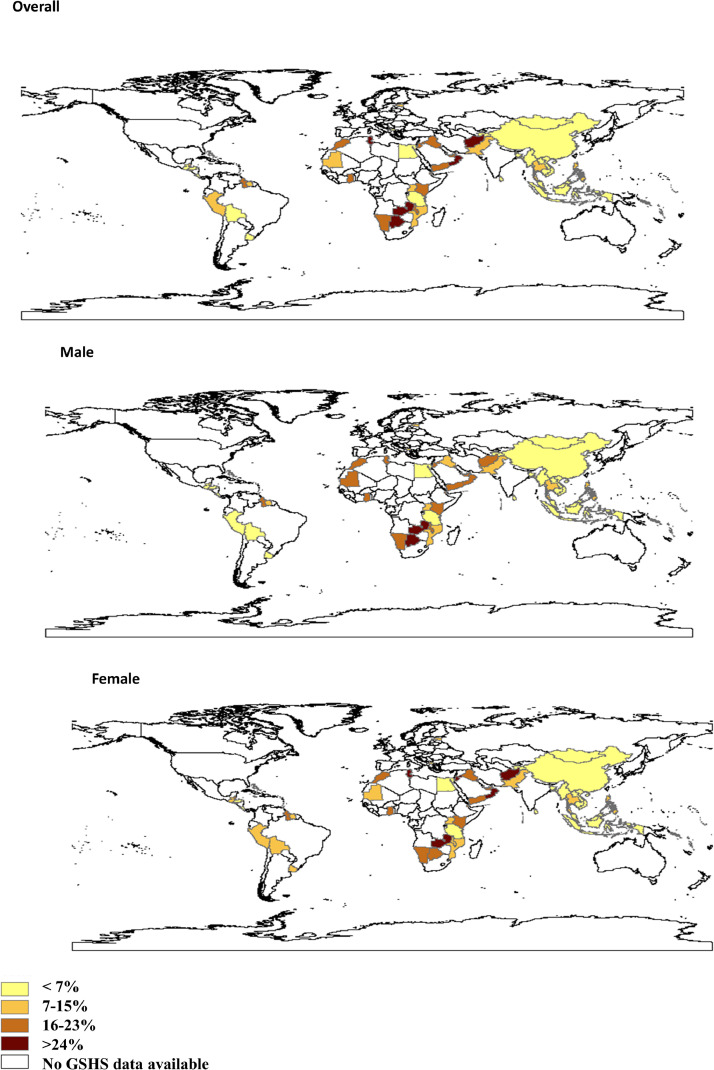

The overall pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety were 14.0% (95% CI: 10.0–17.0%) and 9.0% (7.0–12.0%) respectively. There was significant regional variation in the prevalence of mental health problems. The highest pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation was observed in the Africa Region (21.0%; 20.0–21.0%) and the lowest was in the Asia region with 8.0% (8.0–9.0%; Fig. 1). The highest pooled prevalence of anxiety was observed in Eastern Mediterranean Region (17.0%, 16.0–17.0%) whereas the lowest prevalence of anxiety was in the European Region (4.0%, 4.0–5.0%).

Figure 1.1. and 1.2.

Fig. 1.1.

Pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety, by WHO region, among adolescents aged 12–17 years.

Fig.. 1.2.

Pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety, by the World Bank income groups, among adolescents aged 12–17 years.

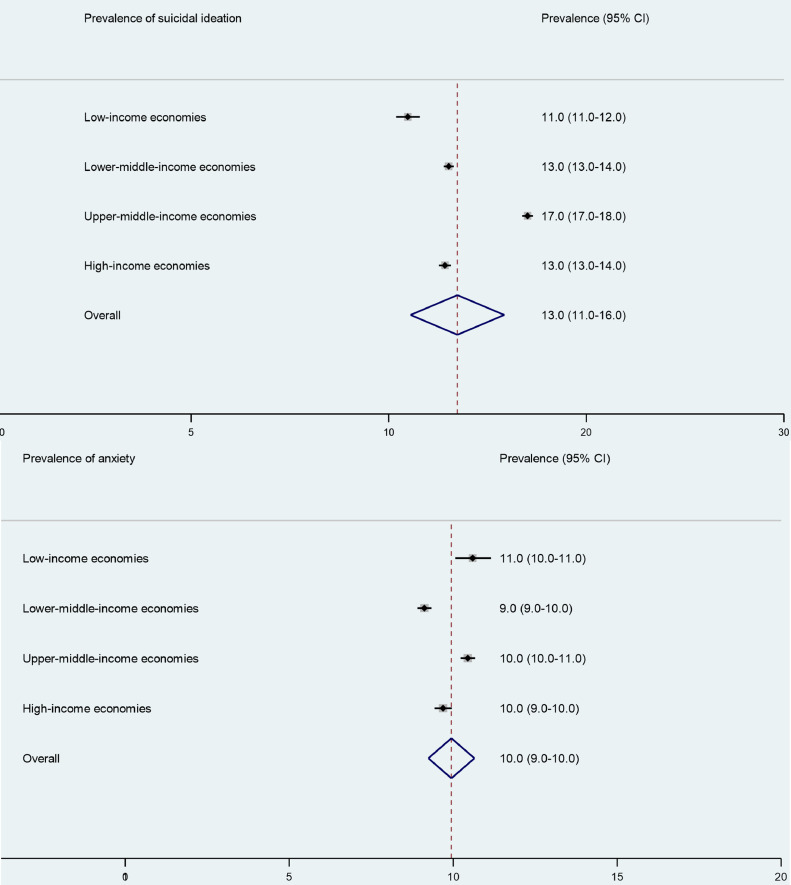

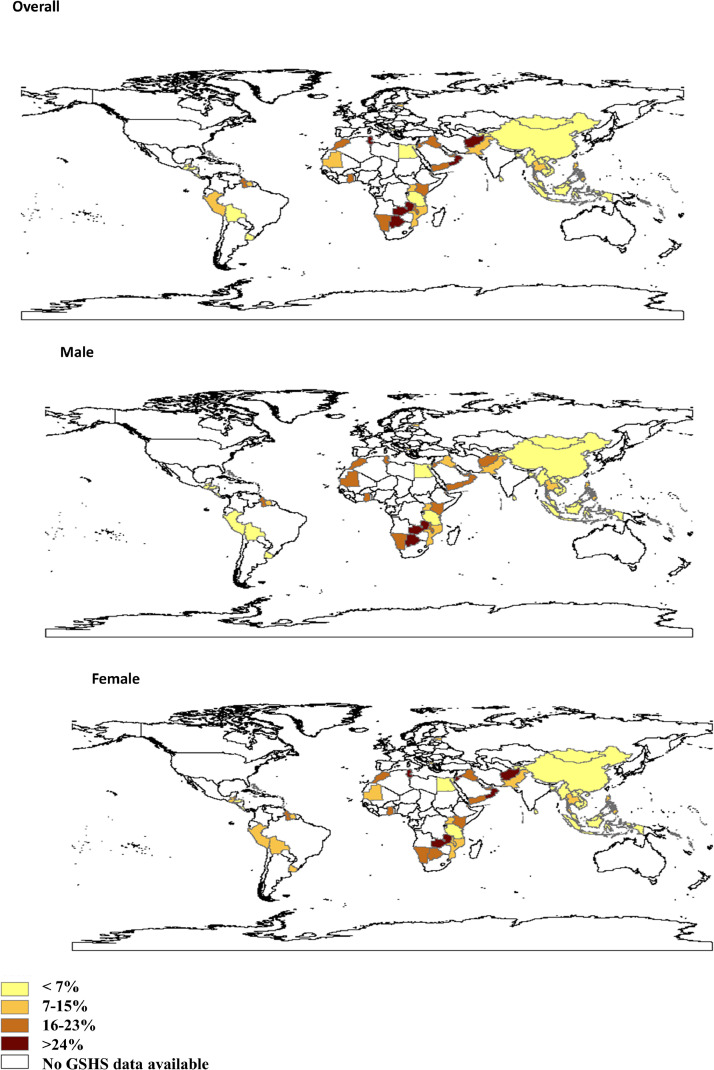

Figure 2.1. and 2.2.

Fig.. 2.1.

Prevalence of suicidal ideation among adolescents aged 12–17 years for 82 LM-HICs, 2003–2015.

Fig.. 2.2.

Prevalence of anxiety among adolescents aged 12–17 years for 82 LM-HICs, 2003–2015.

According to the country income classification, pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation among the adolescents was highest in upper-middle-income countries (17.0%; 17.0–18.0%) and lowest in lower-income group of LMICs (11.0%; 10.0–12.0; Fig. 1). On the other hand, pooled prevalence of anxiety (10.0%, 10.0–11.0%) was highest in lower-income economies and lowest in Lower-middle-income economies countries (9.0%, 9.0–10.0%). Similarly, there was wide variation in the mental health problems at the country level. The country-specific prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety are presented in Fig. 2. Prevalence of suicidal ideation ranged from 1.0% in Myanmar to 40.0% in Samoa. Prevalence of anxiety ranged from 2.0% in Myanmar to 84.0% in Djibouti (Fig. 2). A large variation in prevalence among both male and female adolescents was observed (Fig. 2). The prevalence of suicidal ideation (male: 10.13% vs female: 13.08%) and anxiety (male: 7.35% vs female: 9.21%) was higher among the female than male adolescents. In almost all countries suicidal ideation and anxiety were more prevalent in adolescent females compared to males (Fig. 2). Countries had two time points data and that information presented in supplementary Table 2.

Table 1 shows the prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety by age group, socioeconomic status, peer support, parent-adolescent relationship, peer victimization, conflict, isolation and loneliness. Mental health problems were more prevalent in those of older age, those from a lower SES, and those without peer support. Almost without exception, suicidal ideation and anxiety in adolescents was negatively associated with higher levels of peer support and parental support (table 1). At the same time, suicidal ideation and anxiety were positively associated with greater parental control, peer victimization, conflict, isolation and loneliness.

Table. 1.

Prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety by age group, socioeconomic status, parent-adolescent bonding, peers support, peers victimization, peers conflict, peers isolation.

| Variables | Suicidal ideation (%, 95% CI) | Anxiety (%, 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Boys | 10.1 (9.8–10.5) | 7.4 (7.1–7.7) |

| Girls | 13.1 (12.7–13.5) | 9.2 (8.9–9.5) |

| Age | ||

| 12–13 years | 9.3 (8.9–9.7) | 6.8 (6.4–7.1) |

| 14–15 years | 11.6 (11.2–12) | 8.3 (8–8.6) |

| 16–17 years | 14.3 (13.6–15) | 10.6 (10.1–11.1) |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Average | 10.9 (10.6–11.2) | 7.2 (6.8–7.2) |

| Below average | 13.1 (12.7–13.6) | 10.1 (10.4–11.3) |

| Close friends | ||

| No | 24.3 (22.9–25.8) | 12.7 (11.7–13.7) |

| Yes | 10.7 (10.5–11) | 7.9 (7.7–8.1) |

| Peers supportive | ||

| Never/rarely | 15.1 (14.5–15.7) | 10.5 (10.1–11.3) |

| Sometimes | 10.1 (9.6–10.5) | 6.8 (6.5–7.2) |

| Most of the times | 9.5 (8.9–10.1) | 7.8 (7.3–8.3) |

| Always | 9.1 (8.5–9.6) | 7.8 (7.3–8.3) |

| Parental understanding | ||

| Never/rarely | 15.5 (15.1–16.3) | 10.6 (10.2–11.0) |

| Sometimes | 10.1 (9.6–10.6) | 6.4 (6.3–6.7) |

| Most of the times | 8.4 (7.9–9.1) | 7.3 (6.8–7.8) |

| Always | 8.5 (8.1–8.9) | 7.3 (6.8–7.7) |

| Parental Monitoring | ||

| Never/rarely | 15.4 (14.9–16) | 10.1 (9.6–10.4) |

| Sometimes | 10.4 (9.9–11) | 7.2 (6.8–7.6) |

| Most of the times | 9.1 (8.6–9.7) | 7.8 (7.3–8.4) |

| Always | 8.7 (8.3–9.1) | 7.2 (6.8–7.6) |

| Parental control | ||

| Never/rarely | 9.8 (9.5–10.2) | 7.1 (6.8–7.4) |

| Sometimes | 10.8 (10.1–11.6) | 7.3 (6.7–7.9) |

| Most of the times | 15.8 (14.3–17.4) | 13.2 (11.9–14.6) |

| Always | 14.3 (13.1–15.8) | 11.8 (10.7–13.1) |

| Peer conflict | ||

| No | 9.3 (9.0–9.6) | 6.4 (6.2–6.7) |

| Yes | 15.8 (15.2–16.3) | 12.5 (12.1–13.3) |

| Peer victimization | ||

| No | 9.2 (8.8–9.5) | 6.6 (6.3–6.8) |

| Yes | 13.4 (12.9–13.9) | 10.5 (10–10.9) |

| Peer isolation | ||

| No | 8.1 (7.8–8.4) | 5.4 (5.2–5.6) |

| Yes | 17.3 (16.7–17.9) | 14 (13.5–14.5) |

| Loneliness | ||

| No | 10.0 (9.4–9.9) | 6.0 (5.3–5.7) |

| Yes | 27.0 (26.1–28.3) | 30.0 (29.4–31.6) |

Table 2 shows the multivariate associations (adjusted model) of suicidal ideation and anxiety for the overall sample and supplementary Table 3–4 by WHO region. Overall, mental health problems were associated with being female, older age, and having a lower socioeconomic status and an absence of close friends. For example, suicidal ideation was higher among females (OR; 1.68; 95% CI: 1.55–1.81) older age (1.55; 1.41–1.71), and having a lower socioeconomic status (1.10; 1.01–1.19) and those reporting no close friends (2.14; 1.87–2.46) compared to their counterparts. Those adolescents who perceived they experienced parental understanding and experienced more parental monitoring had significantly lower rates of suicidal ideation (0.69; 0.61–0.79) and (0.68; 0.62–0.76) respectively. Conversely, suicidal ideation and anxiety were more likely to be reported by those adolescents who perceived higher levels of parental control (1.65; 1.45–1.87; and 1.53; 1.30–1.80 respectively). Similarly, peer victimization, peer conflict, peer isolation and loneliness were all strongly correlated with suicidal ideation and anxiety. For example, anxiety was higher among adolescents who had experienced peer conflict (1.54; 1.40–1.70), peer victimization (1.13; 1.02–1.26), peer isolation (1.76; 1.61–1.92) or reported loneliness (5.63; 5.21–6.08) compared to those who did not endorse these items.

Table. 2.

Multiple logistic regression analysis (adjusted ORs) to identify factors associated with suicidal ideation and anxiety among the young adolescent.

| Suicidal ideation |

Anxiety |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | p- value | OR (95% CI) | p- value |

| Sex | ||||

| Boys | Ref | Ref | ||

| Girls | 1.68 (1.55–1.81) | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.36–1.65) | <0.001 |

| Age | ||||

| 12–13 years | Ref | Ref | ||

| 14–15 years | 1.22 (1.11–1.34) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.08–1.31) | <0.001 |

| 16–17 years | 1.55 (1.41–1.71) | <0.001 | 1.68 (1.49–1.9) | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Average | Ref | Ref | ||

| Below average | 1.10 (1.01–1.19) | 0.032 | 1.30 (1.19–1.42) | <0.001 |

| Close friends | ||||

| No | 2.14 (1.87–2.46) | <0.001 | 1.06 (0.88–1.28) | 0.551 |

| Yes | Ref | Ref | ||

| Peers supportive | ||||

| Never/rarely | Ref | Ref | ||

| Sometimes | 0.76 (0.68–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.72–0.96) | 0.011 |

| Most of the times | 0.77 (0.68–0.87) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.84–1.11) | 0.582 |

| Always | 0.78 (0.7–0.87) | <0.001 | 1.03 (0.91–1.17) | 0.641 |

| Parental understanding | ||||

| Never/rarely | Ref | Ref | ||

| Sometimes | 0.77 (0.68–0.87) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.65–0.83) | <0.001 |

| Most of the times | 0.61 (0.55–0.69) | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.7–0.95) | 0.010 |

| Always | 0.69 (0.61–0.79) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.81–1.06) | 0.273 |

| Parental monitoring | ||||

| Never/rarely | Ref | Ref | ||

| Sometimes | 0.77 (0.69–0.86) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.8–1.04) | 0.158 |

| Most of the times | 0.67 (0.6–0.74) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.81–1.1) | 0.440 |

| Always | 0.68 (0.62–0.76) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.8–1.06) | 0.256 |

| Parental control | ||||

| Never/rarely | Ref | Ref | ||

| Sometimes | 1.27 (1.13–1.42) | <0.001 | 1.09 (0.94–1.26) | 0.241 |

| Most of the times | 1.60 (1.35–1.89) | <0.001 | 1.69 (1.44–1.98) | <0.001 |

| Always | 1.65 (1.45–1.87) | <0.001 | 1.53 (1.30–1.80) | <0.001 |

| Peer conflict | ||||

| Yes | 1.36 (1.24–1.5) | <0.001 | 1.54 (1.40–1.70) | <0.001 |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Peer victimization | ||||

| Yes | 1.26 (1.15–1.38) | <0.001 | 1.13 (1.02–1.26) | 0.019 |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Peer isolation | ||||

| Yes | 1.69 (1.53–1.86) | <0.001 | 1.76 (1.61–1.92) | 0.000 |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Loneliness | ||||

| Yes | 2.56 (2.33–2.82) | <0.001 | 5.63 (5.21–6.08) | <0.001 |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

*Adjusted by survey year, gender, age, socioeconomic status, peer support, parent-adolescent bonding, injuries, violence and loneliness.

4. Discussion

The present study based on the GSHS data provides the most comprehensive summary to date of the prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety among adolescents across 82 HIC-LMICs from six WHO regions. This is the first global study of its kind to examine the relationship between suicidal ideation and anxiety with peer and parental relationships in a wide range of countries. There are four major findings. First, a high prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety was observed in most of the 82 countries, irrespective of income classification. Second, there was a wide variation between countries in the prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety. Third, there were strong and consistent associations between suicidal ideation and anxiety in adolescents and the nature of the relationships they had with their parents and peers across all world regions. Finally, negative experiences with peers such as peer victimization, conflict, isolation and loneliness were strongly correlated with suicidal ideation and anxiety.

A previous study of 59 LMICs using GSHS data reported that the prevalence of suicidal ideation was 16.9% [15]. Studies in Nepal and China [22]. reported that the prevalence of suicidal ideation was 13.6% in general, and 17.4% among adolescents [23]. We found a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety in females compared to male adolescents which aligns with a study of loneliness among adolescents in the US, Czech Republic and Russia [24]. The higher prevalence of suicidal ideation among female adolescents is consistent with other studies of internalizing disorders for example, higher rates of any mood disorder among females (18.3%) than males (10.5%) [25]. Suicidal ideation is only loosely connected with completed suicide which is higher among males. It is likely that suicidal ideation is a proxy for psychological distress. Its higher prevalence in female adolescents, especially in LMICs may be explained by a range of biopsychosocial factors which would include gender inequity, a tendency for females to internalize their distress more than males, greater exposure of females to forms of maltreatment, particularly childhood sexual abuse in addition to biological factors such as estrogen [26].

Adolescents who reported they had higher levels of peer support, parental understanding and monitoring had significantly lower rates of mental health problems. Conversely suicidal ideation and anxiety were approximately double in adolescents who perceived high levels of parental control. Other studies have also reported child anxiety to be significantly associated with observed parental control [27], [28], [29], [30]. Aligned to our findings, other studies have also highlighting the relationship between peer support, paternal relationship and depressive symptoms in adolescents [31,32]. At the same time both cross-sectional and longitudinally studies reported, higher levels of peer support also predict reduced onset of depressive symptoms over time [32,33].

Resources for mental health services in LMICs are scarce. The World Health Assembly adopted the Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 [33]. However, of the 82 countries in this study, 36 countries have no specific mental health policy (Supplementary figure-1). The strong association between parental and peer relationships on adolescent anxiety and suicidal ideation should inform national policies to improve population mental health. Culturally appropriate interventions that modify the parent- adolescent relationship and promote the adolescent's individuation-separation whilst maintaining parental monitoring and understanding may also promote mental wellbeing in adolescents. Similarly, establishing school-based programmes or community activities that increase peer connectedness may also help reduce distress, anxiety, and alleviate progression to suicidal ideation.

The present study needs to be viewed in the context of a number of important limitations. First, there is a risk of selection bias because school attendance is low in some counties and only children that attend school participated. Non-attendance at school is differentially likely to be more so among students in LMICs than in HICs. Further, some students were absent from school on the day of data collection. Second, suicidal ideation and anxiety were each measured in the GSHS using a single self-report item. While self-report is an accepted method of measuring suicidal ideation and anxiety in adolescents, there is a limitation of possible shared method variance. Further, there would be cultural and legal factors that might influence self-report, particularly of suicidal ideation. For example, in some countries, suicide is illegal (eg India, Singapore and Kenya) and discussion of suicidal ideation is discouraged. Another limitation is the measure of socioeconomic status, peer support, parent-adolescent relationship, peer victimization, conflict, isolation which were based on a proxy measures generally derived from a single item. Some regions (European and African) were not well represented in the study. The study design was cross-sectional, therefore the temporality between the variables in unclear and causality must not be inferred.

On the other hand, the study has a number of strengths that help us to uniquely estimate the global prevalence of suicidal ideation and anxiety amongst adolescents in various settings. First, the GSHS methodology uses a standardized questionnaire. Collection of the data was standardized and always occurred during a regular class period. The questionnaire did not allow skip patterns in questions enabling consistency and uniformity of comparison across participant sites. Another strength is the use of survey data with large random sample sizes taken from a wide variety of international geographical and cultural settings. Finally, the analyses were inclusive of data from 82 countries.

Mental health problems such as suicidal ideation and anxiety in adolescents are a major public health concern globally [34]. Although there is enormous global variation, there is consistency across cultures and across country development status (LMIC vs HIC) that mental health in adolescents is strongly influenced by parental and peer relationships. Similarly, there is a consistently higher prevalence of mental ill-health in female adolescents compared with males. These findings are important to inform national and global policies and related actions to address adolescent suicidal ideation and anxiety. Adolescent suicidal ideation and anxiety prevention strategies should include female-specific initiatives, family and peer relationships which are sociocultural specific and sensitive. Given the substantial variation among countries and regions, more work is needed to understand the sociocultural context of the antecedents of adolescents’ mental health related behaviours in low-income and middle-income countries.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

All authors critically reviewed earlier versions of the draft and approved the final manuscript. TB and AAM conceived the paper. TB, JGS and AAM developed the analysis plan. TB did the analysis and wrote the initial draft. AMNR, KM, LBR and JB contributed to the write up and editing.

Declaration of interests

All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank the US Centers for Disease Control and WHO for making Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) data publicly available for analysis. We thank Md. Mehedi Hasan, for helping us data management. This research was partially supported by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (project number CE140100027). James Scott is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship Grant (APP1105807).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100395.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Magadi MA. multilevel determinants of teenage childbearing in sub-saharan Africa in the context of Hiv/aids. Health & place. 2017;46:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss HA, Ferrand RAJTL. Improving adolescent health: an evidence-based call to action 2019;393(10176): 1073-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent development. Annual review of psychology. 2001;52(1) doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patton GC, Olsson CA, Skirbekk V, et al. Adolescence and the next generation 2018;554(7693): 458. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.The LJL Health an afterthought in a single-issue election 2017;389(10080):1670. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Erskine H, Moffitt TE, Copeland W. A heavy burden on young minds: the global burden of mental and substance use disorders in children and youth. Psychological medicine. 2015;45(7):1551–1563. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

- 8.Moore GF, Cox R, Evans RE, et al. School, peer and family relationships and adolescent substance use, subjective wellbeing and mental health symptoms in wales: a cross sectional study 2018;11(6): 1951-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Tough H, Siegrist J, Fekete CJBph. Social relationships, mental health and wellbeing in physical disability: a systematic review2017;17(1): 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Bowes L, Maughan B, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Arseneault LJJoCP, Psychiatry Families promote emotional and behavioural resilience to bullying: evidence of an environmental effect2010;51(7): 809-17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Nguyen HTL, Nakamura K, Seino K, Al-Sobaihi SJBp. Impact of parent–adolescent bonding on school bullying and mental health in Vietnamese cultural setting: evidence from the global school-based health survey2019;7(1): 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Sweeting H, Young R, West P, Der GJBjoep. Peer victimization and depression in early–mid adolescence: A longitudinal study2006;76(3): 577-94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, et al Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action2011;378(9801): 1515-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA. Annual Research Review: A meta‐analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015;56(3):345–365. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uddin R, Burton NW, Maple M, Khan SR, Khan AJTLC. Health A Suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts among adolescents in 59 low-income and middle-income countries: a population-based study 2019;3(4): 223-33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Jordans M, Rathod S, Fekadu A, et al. Suicidal ideation and behaviour among community and health care seeking populations in five low-and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study 2018;27(4): 393-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Le MTH, Nguyen HT, Tran TD, Fisher JRJJoah. Experience of low mood and suicidal behaviors among adolescents in Vietnam: findings from two national population-based surveys 2012;51(4): 339-48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.WHO Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS); http://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/en/ (accessed July 25).

- 19.https://www.cdc.gov/gshs/background/pdf/gshs-data-users-guide.pdf.

- 20.Biswas T, Scott JG, Munir K, et al. Global variation in the prevalence of bullying victimisation amongst adolescents: Role of peer and parental supports. 2020: 100276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Rao S, Shah N, Jawed N, Inam S, Shafique KJBph Nutritional and lifestyle risk behaviors and their association with mental health and violence among Pakistani adolescents: results from the National Survey of 4583 individuals2015;15(1): 431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Cheng Y, Tao M, Riley L, et al Protective factors relating to decreased risks of adolescent suicidal behaviour2009;35(3): 313-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Pandey AR, Bista B, Dhungana RR, Aryal KK, Chalise B, Dhimal MJPo Factors associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts among adolescent students in Nepal: Findings from Global School-based Students Health Survey2019;14(4): e0210383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Stickley A, Koyanagi A, Koposov R. Loneliness and its association with psychological and somatic health problems among Czech. Russian and US adolescents. 2016;16(1):128. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0829-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, Kessler RC. Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents 2009;11(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Altemus M, Sarvaiya N, Epperson CNJFin. Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. 2014;35(3): 320-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Van Der Bruggen CO, Stams GJJ, Bögels SMJJoCP, Psychiatry Research Review: The relation between child and parent anxiety and parental control: a meta‐analytic review2008;49(12): 1257-69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.De Rosnay M, Cooper PJ, Tsigaras N, Murray LJBr, therapy Transmission of social anxiety from mother to infant: An experimental study using a social referencing paradigm2006;44(8): 1165-75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Gerull FC, Rapee RMJBr, therapy. Mother knows best: effects of maternal modelling on the acquisition of fear and avoidance behaviour in toddlers2002;40(3): 279-87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Waite P, Whittington L, Creswell CJPR. Parent-child interactions and adolescent anxiety: A systematic review2014;1(1): 51-76.

- 31.MacPhee AR, Andrews JJJA. Risk factors for depression in early adolescence 2006;41(163): 435. [PubMed]

- 32.Chester C, Jones DJ, Zalot A, Sterrett EJJoCC, Psychology A The psychosocial adjustment of African American youth from single mother homes: The relative contribution of parents and peers 2007;36(3): 356-66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Allen JP, Insabella G, Porter MR, et al A social-interactional model of the development of depressive symptoms in adolescence. 2006;74(1): 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Saxena S, Funk M, Chisholm DJTLWorld health assembly adopts comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020 2013;381(9882): 1970-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.