Abstract

Rational & Objective

A key aspect of smooth transition to dialysis is the timely creation of a permanent access. Despite early referral to kidney care, initiation onto dialysis is still suboptimal for many patients, which has clinical and cost implications. This study aimed to explore perspectives of various stakeholders on barriers to timely access creation.

Study Design

Qualitative study.

Setting & Participants

Semi-structured interviews with 96 participants (response rate, 67%), including patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (n = 30), new hemodialysis patients with (n = 18) and without (n = 20) permanent access (arteriovenous fistula), family members (n = 19), and kidney health care providers (n = 9).

Analytical Approach

Thematic analysis.

Results

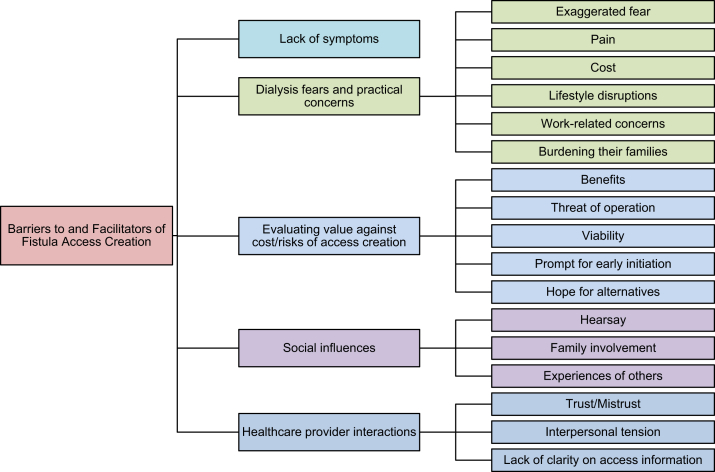

Patients reported differential levels of behavioral activation toward access creation: avoidance/denial, wait and see, or active intention. 6 core themes were identified: (1) lack of symptoms, (2) dialysis fears and practical concerns (exaggerated fear, pain, cost, lifestyle disruptions, work-related concerns, burdening their families), (3) evaluating value against costs/risks of access creation (benefits, threat of operation, viability, prompt for early initiation), (4) preference for alternatives, (5) social influences (hearsay, family involvement, experiences of others), and (6) health care provider interactions (mistrust, interpersonal tension, lack of clarity in information). Themes were common to all groups, whereas nuanced perspectives of family members and health care providers were noted in some subthemes.

Limitations

Response bias.

Conclusions

Individual, interpersonal, and psychosocial factors compromise dialysis preparation and contribute to suboptimal dialysis initiation. Our findings support the need for interventions to improve patient and family engagement and address emotional concerns and misperceptions about preparing for dialysis.

Index Words: Fistula, access creation, decision making, qualitative study, delay, chronic kidney disease, renal failure, renal replacement therapy

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a growing health problem that affects >10% of the world’s population.1 With aging and an increase in diabetes, end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) and the demand for dialysis will continue to increase. Key to a smooth transition from ESKD to dialysis is the optimal and timely preparation for kidney replacement therapy (KRT), that is, dialysis initiation with a permanent access (arteriovenous fistula [AVF] or arteriovenous graft for hemodialysis [HD] and a Tenckhoff catheter for peritoneal dialysis).2 Permanent access creation is associated with benefits for patients and health care systems alike, including lower costs, better patency, lower risk for infections and associated hospitalization events, and decreased mortality.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Rates of patients starting HD with permanent access are poor. Data from the US Renal Data System11 indicate that 80% of patients initiated HD with a temporary central venous catheter. Similarly, a study in Singapore found incidence rates of 44.1% and 85.7% for patients who had a dialysis plan and those who did not, respectively.3 These rates occur despite the clear specification of predialysis care pathways and international guidelines for timely referral for vascular access creation. Systemic and provider factors such as delays, late referral to kidney care, and no predialysis education12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 are important barriers yet cannot fully account for the observed trends. Patient-related barriers have received relatively little attention.12 Delay behaviors such as hesitation to receive predialysis education, defaulting appointments, reluctance to discuss dialysis,15 or refusal to make decisions related to dialysis or access12,13,16,17,19,20 are not well understood. Clinical uncertainty around disease progression further exacerbates patients’ inertia to preparing for dialysis because they often wait and see, leading to unplanned dialysis initiation.21

Systematic reviews of studies based on mainly established HD patients20,22 indicate that concerns related to vascular access and treatment burden are dominant treatment stressors. However, the accounts of patients already on KRT may be subject to recall bias, making their views of limited value.23 Reviews of medical records are informative of system/provider factors but do not document patient-related barriers24,25 or at best rely on indirectly inferred patient information. There remains limited work on patients with CKD not yet on dialysis but at the point of delaying dialysis preparation. Similarly, little is known about the perspectives of family members and kidney health care providers, who are potential powerful influences on patients’ decisions regarding starting HD with permanent access. As shown in the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology (SONG) initiatives,26 it is important to map patient-prioritized outcomes, yet there has been no focus specifically on the predialysis pathway.

This study aimed to synthesize the perspectives of patients with CKD (newly initiated HD patients and those currently deciding on access), family members, and health care providers on the issue of dialysis preparation and identify factors that facilitate or hinder timely access creation. A qualitative methodology was used to obtain perspectives without constraining participants to the limitations of a predetermined questionnaire. The focus was specifically on patients already in kidney care and exposed to predialysis education. By gaining a better understanding of this critical element of KRT, it is hoped that opportunities for improvements to kidney services and predialysis education can be identified.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore enablers and barriers to timely preparation for dialysis. Ethical approval was obtained by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (reference number: 2015/01225) and SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (reference number: 2016/2979). We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines.27

Setting and Participants

The study was conducted in 2 government-funded hospitals (Singapore General Hospital and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital) in Singapore from 2015 to 2017. The respective nephrology departments have similar care pathways and serve patients from diverse demographic backgrounds. All patients with CKD are promptly referred to predialysis education session(s) to support them in the process of selecting a treatment modality among those modalities clinically feasible for them. The predialysis education program involves 1-to-1 session(s) with kidney coordinators (typically specialist nurses). Written and audiovisual materials and resources are used at sessions and to take home. The sessions are conducted in patients’ preferred language and are supported by input from a multidisciplinary care team. Patient advocates who are already on KRT may at times be engaged to support the program, typically by patient request. Most patients undertake these sessions several months before KRT initiation, typically at stage 4 CKD. Kidney care, including predialysis education, is a fee for service in Singapore but subsidies are available to accommodate patients’ socioeconomic circumstances.

To maximize representation of various stakeholders, a combination of purposive and convenience sampling strategies was used to recruit patients with stages 4 to 5 CKD, new HD patients (<6 months) initiated on an emergency catheter, new HD patients initiated on an AVF, family members of patients with stage 4 CKD involved in decisions around dialysis, and kidney health care providers, including nephrologists, nurses, social workers, and kidney coordinators.

Eligibility criteria, which were determined by health care staff on site, included adults (aged >21 years) who had attended at least 1 KRT counseling session. Participants were excluded if they did not speak English, Malay, or Mandarin (the nation’s main spoken languages); had opted for conservative management; or had conditions (ie, functional psychosis or dementia/learning disabilities) that would prevent consent. Target sample size was 15 to 20 individuals per group as per recommendations to achieve theme saturation.28 Recruitment stopped when no new topics emerged in 2 consecutive interviews.

Data Collection

Eligible participants were approached at the clinic and interviewed by researchers independent from the kidney care team. Prior written consent to participate and for the interview to be audiorecorded was obtained before data collection. Sociodemographic information, including age, sex, ethnicity, employment, education, and marital status, were self-reported. Medical/serologic data (eg, estimated glomerular filtration rate, comorbid conditions, and primary ESKD diagnosis) were abstracted from medical records.

The interviews lasted 30 to 60 minutes and were conducted in the participants’ preferred language (English, Malay, or Mandarin) without an interpreter. The interviewers (Z.S.G., P.S.S., and Vanessa Lee) were all bilingual graduate psychologists (BSc(Hon) and/or MSc) with prior experience in qualitative methodology and analyses. They were supervised by K.G. The interview guide, developed following literature and experts’ review, included the following topics: participants’ experiences with discussions related to dialysis access and health system navigation, their decision-making process, influencers and considerations, and concerns related to access (see Item S1 for English language topic guides). The interview guide was pilot tested with 2 stakeholders (1 provider and 1 patient or family member) and refined based on their feedback. Interviews were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. Non-English interviews were translated. To validate the translations, 20% of transcripts were independently translated by a lay translator (κ > 0.98). Field notes were taken immediately after interviews.

Analytical Approach

An inductive thematic analysis approach that uses the steps of familiarization, coding, theme development, reviewing themes, defining themes, and reporting was applied to identify barriers and facilitators for the 3 groups of participants: patients, family members, and health care providers.29 All interviews were coded by 2 coders. Specialist software was not used. Initial codes and preliminary codebooks of emerging themes per group of participants were iteratively refined after 2 coders reached agreement. These preliminary codebooks were applied to all subsequent interviews for each group of participants. Researcher reflexivity was supported by regular meetings with the research group in which themes (including illustrative quotes) and codebooks were reviewed and refined. All themes and codebooks for the 3 groups of participants were reviewed and contrasted and a final master codebook was collaboratively developed, expanding and collapsing themes to reflect all 3 participant groups. Language of the interview was not analyzed separately due to homogeneity in themes. The final codebook was used to recode all transcripts. Coded quotes were organized by theme, subtheme, and participant type (patient or family member or health care providers). We followed the recommendations outlined in COREQ to report study findings.27

Results

A total of 147 eligible participants were approached, and 97 consented to participate (response rate, 66%). Reasons for nonparticipation included being uninterested and having no time. One patient from the CKD4 group was excluded ad hoc because inclusion criteria were not met. The final sample comprised 96 participants: CKD4, n = 30; HD with catheter, n = 20; HD with AVF, n = 18; family members, n = 19; and health care providers, n = 9. A total of 57 (59.4%) interviews were conducted in English; 37 (38.5%), in Mandarin; and 2 (2.1%), in Malay (Table 1; see Table S1 for characteristics of family members and health care providers).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patient Participants

| Group | Total (N = 96) | CKD4 (N = 30) | HD on Catheter (N = 20) | HD on AVF (N = 18) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 59.3 ± 12.2 | 66.2 ± 9.9 | 59.1 ± 7.5 | 61.0 ± 9.3 |

| Men | 52 (54.2%) | 21 (70%) | 11 (55%) | 12 (66.6%) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Chinese | 68 (71%) | 22 (73%) | 13 (65%) | 13 (72.2%) |

| Malay | 21 (22%) | 6 (20%) | 4 (20%) | 4 (22.2%) |

| Indian | 5 (5%) | 2 (7%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Other | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Relational status | ||||

| Married | 44 (66.7%) | 18 (64.3%) | 14 (70%) | 12 (66.7%) |

| Divorced | 5 (7.6%) | 2 (7.1%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Widowed | 6 (9.1%) | 3 (10.7%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Other | 11 (16.7%) | 5 (17.9%) | 2 (10%) | 4 (22.2%) |

| Cause of ESKD | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 19 (63.3%) | 12 (60%) | 14 (77.8%) | |

| Hypertension | 5 (16.7%) | 5 (25%) | 2 (11.1%) | |

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 3 (10%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (5.6%) | |

| Others | 3 (10%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5.6%) | |

| Months in kidney care (1st appointment with nephrologist) | 38.1 ± 31.0 | 43 ± 33.7 | 36.7 ± 36.5 | 31.7 ± 16.7 |

| Months since 1st appointment with kidney coordinator | 20.8 ± 19.1 | 26.2 ± 24.4 | 13.0 ± 10.5 | 20.3 ± 13.3 |

| Time on HD, mo | 2.35 ± 1.84 | 3.67 ± 2.09 | ||

| Access already created (CKD4 group) | ||||

| None | 20 (66.7%) | |||

| AVF | 10 (33.3%) | |||

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 (CKD4 group only) | 11 ± 4.51 |

Note: Values expressed as number (percent) unless otherwise noted. See characteristics of family members and providers in Table S1.

Abbreviations: AVF, arteriovenous fistula; CKD4, chronic kidney disease stage 4; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration); ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; HD, hemodialysis.

Levels of Behavioral Activation

The stance of patients regarding access creation is frequently dynamic and oscillating. Three levels of behavioral activation toward access creation emerged in patient interviews: avoidance/denial, wait and see, and active intention (Table 2). Patients in avoidance/denial were reluctant to talk about dialysis and often resistant to information from health care providers. They refused to engage in conversations about dialysis access, and some even denied the severity of their condition and need for KRT. Patients with the wait-and-see stance recognized the severity of kidney function decline, but were not convinced of the urgent need to act on access creation. They accepted the prospect of dialysis but preferred the status quo and hence took no action. Some expressed the intention to wait until an emergency before proceeding with access creation. However, patients with an active intention accepted the severity of their condition and the need for dialysis and recognized the value of timely preparation and permanent access creation.

Table 2.

Levels of Behavioral Activation Toward Access Creation in Patients

| Illustrative Quotes |

| Avoidance/Denial |

| “I was undecided and very confused. I was even thinking maybe I don’t need to go through all these. All the dialysis, all the operations and all that. At first you will tend to have [this] escapist mind. Yes, I keep on thinking maybe I will be special. You don’t tend to believe in it. Maybe it’s not that bad, maybe they made a wrong diagnosis. At that point I felt that I was just listening to her [doctor] talk and then get out. You just want to shut your mind off.” (HD patient with catheter) |

| “Actually the dialysis thing is already out of mind. It’s only when somebody mention then I bring it up from my mind to you. If not, I put aside. I put aside, that’s why I told the coordinator be happy and I put aside.” (CKD4 patient) |

| Wait and See |

| “I will decide it later on when it is unbearable.” (HD patient with catheter) |

| “I feel that me doing dialysis, it’s a matter of time. My kidney functioning index will not get better. I tried my best to take medicine and try to delay as much as possible. I was hopeful.” (CKD4 patient) “I say, see a few years later. Wait till I act up then see how… I was unwilling to go… keep unwilling to go. Only wait till when I feel very lethargic in my whole body can’t get up then no choice I go.” (HD patient with catheter) |

| Active Intention |

| “I thought it [dialysis] will be coming very fast the way things are. So be prepared for it, so I need to do that [AVF].” (CKD4 patient) |

| “Because confirm I will be going for dialysis so it’s better to go for one operation instead of two.” (HD patient with AVF) “From blood test it shows that your kidney is not good. Don’t waste time, the more you wait, maybe the more [the] problem [will] affect other areas… at the end of the day I think dialysis is still the answer.” (HD patient with AVF) |

Abbreviations: AVF, arteriovenous fistula; CKD4, chronic kidney disease stage 4; HD, hemodialysis.

Health care providers recognized patient hesitation and resistance toward dialysis. The term denial was often used to collectively refer to patients’ disengagement with services, including defaulting care, inertia in terms of decision making, or actions, such as following up with referrals related to access. They remarked that although systemic barriers related to referrals have been to a great extent circumvented, the most common barrier is patient avoidance of dialysis discussions and preparation. Health care providers also recounted how patients even when attending kidney appointments would disengage, for example by looking away, being impatient during the consultations, or avoiding any verbal commitment or action toward dialysis preparation.

Analyses revealed 6 superordinate overarching themes related to levels of behavioral activation: (1) lack of symptoms, (2) dialysis fears and practical concerns (exaggerated fear, pain, cost, lifestyle disruptions, work-related concerns, and burdening their families), (3) evaluating value against costs/risks of access creation (benefits, threat of operation, viability, and prompt for early initiation), (4) hope for alternatives, (5) social influences (hearsay, family involvement, and experiences of others), and (6) health care provider interactions (mistrust, interpersonal tension, and lack of clarity on information; see Table 3 for themes and illustrative quotes across groups of participants and Figure 1 for thematic schema).

Table 3.

Factors Influencing Behavioral Activation Toward Access Creation

| Themes | Illustrative Quotes |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Family Members | Health Care Providers | |

| Lack of symptoms | “Yeah, I won't be convinced until I feel that there is something wrong with my body and I will go for it [AVF preparation and dialysis].” (CKD4 patient) I can walk, I can run, I can eat, I can drink and I got no problem.” (HD patient with catheter) |

“Now I think he still can walk and exercise, so I don't care about it much. If the condition won’t worsen and stabilizes like this then it will be okay.” | “Sometimes if the patient doesn’t have any symptoms…or the patient has lack of knowledge, most of the time the patient will decline the dialysis” (kidney doctor) “…the lack of symptoms…, they don’t see a real need because their life is well. They can eat, they can sleep well” (kidney coordinator) |

| Dialysis Fears and Practical Concerns | |||

| Exaggerated fear | “In my concept… dialysis is like… a handicapped person. He can’t do anything, he is just bed ridden.” (HD patient with AVF) “I said gone, that’s it, that’s it. This is the end… this is the end of me.” (HD patient with catheter) |

“Dialysis is tantamount to doomsday.” “Yes, I saw and was afraid. When I see people come back after dialysis, they looked very exhausted. That’s why I hope he doesn't need to go for dialysis.” |

“When I ask them what dialysis means to them, some of them told me that, ‘It means that your life is over, it means the end.’ Some of them say you know, it’s the start of large deterioration on health.” (kidney coordinator) |

| Pain | “… When you go [on] dialysis they will poke you with needle everything you feel the pain. They might say a small ant bite but one week three times it’s quite painful.” (HD patient with AVF) | “Because he's [the patient is] very scared of pain also, so uh, I heard it’s quite painful right, dialysis?” | |

| Cost | “My main problem is financial. Number one. I can’t overcome this problem already.” (CKD4 patient) “I really do not have the money to go for dialysis. Where can I get the money to go for dialysis? This is a rich man illness.” (HD patient with AVF) |

“Still need to pay for it, it’s not like it’s free. 3 times per week needs a lot of money right. She’s [patient] not working, who is going to support her?” | “The fear of financial burden is very very big. They said it’s very expensive, always very expensive like, ‘I can’t afford it.’ And just erm, ‘I don’t make much money,’ ‘I’m not a high incomer.’ (kidney coordinator) |

| Lifestyle disruptions | “Worry about affecting my lifestyle, my job… Maybe social… so called outing, going out with friends then suddenly cannot make it because of dialysis.” (CKD4 patient) | “I look after my mother also. If my husband do dialysis that means I cannot mix around…That means I cannot enjoy… Because [if] my husband do dialysis very difficult for me to visit my mother and go to my son’s and daughter’s place.” | “Like because once they start on dialysis their lifestyle is going to change as well. So I think they don’t know if they can adjust to this new lifestyle.” (kidney coordinator) |

| Work-related concerns | “There’s no reason that a boss will employ you when you can’t go for work for 3 days per week. I do this (AVF), my boss doesn’t know. I tried to hide it from them, if too many know that you have kidney failure they will ask you don’t need to report to work tomorrow.” (HD patient with AVF) | “A lot of them are thinking about that, ‘you know, if dialysis I can’t work. Because who would want to employ a dialysis patient who have to go to dialysis three times a week.’” (social worker) | |

| Burdening their families | “It’s good for the family (that I don’t dialyze yet). I am not disrupting their lives. If there’s any worries in the family then how are they going to live well?” (CKD4 patient) “I have no savings. I don't want to get from them (daughter and son-in-law)… burden will be too heavy.” (HD patient with AVF) |

“The people who have to look after her, like myself who has to work, and look after her… she feels like she’s going to be a burden.” | “Because of financial issues. They are afraid that it may burden their spouse or their family members, their children.” (kidney coordinator) |

| Evaluating Value Against Costs/Risks of Access Creation | |||

| Benefits | “The dialysis preparation will help you in the sense that, and if its time you need it for emergency it’s already there.” (CKD4 patient) “If you operate, you put it there, then next time got any problem, urgent ah, then dialysis from here. If not have [to] poke needle here, poke needle here… more painful.” (CKD4 patient) |

“The doctor said that…if you do it early you can straightaway start dialysis if need be suddenly, but if you don't do it early it will be more troublesome.” | |

| Threat of operation | “I [have] phobia… I’m scared they want to cut my hand and put inside the tube…painful. Before that they asked me to book [AVF creation appointment], I always run away, I think I ran away 6 times.” (CKD4 patients) “… I don’t want to cut means I don’t want to cut. I understand the procedure. I just don’t want to go operate. Nobody wants to go [for an] operation. They cut here, cut there. I don’t want to go for operation.” (CKD4 patient) |

“We are afraid that the operation will be risky… Because when we were about to have the operation for the fistula, the anaesthetic doctor told us many problems, eg, after operation needs to be very careful so that it wouldn't be affected so have to be very careful that’s why we were a little worried about it.” | “But then the thought of having an operation… is still scary.” (kidney nurse) |

| Viability | “… like (maybe) there will be some complication like bleeding. Then sometimes like it’s not successful. So that’s why make me afraid.” (HD patient with catheter) “At that point in time I was afraid…the doctor told us there are cases whereby the fistula can’t be used for some patients. I was just worried about this.” (HD patient with AVF) |

“What if it [the fistula] spoils again, you will have to do it again. So I was thinking after the operation he was in pain, his arms also no strength, I also think it’s not right… if you create another one as spare, spoil already still need to create another one.” | “Damaged, a lot of them said they heard it [the fistula] can get damaged easily… they will worry that it gets damaged very fast.” (kidney coordinator) “I think the fear of dialysis weighs more than fistula. Once they can get over the dialysis part. Fistula… I try to explain the rationale why must we get it done now… we (can) try to get it done as soon as possible.” (kidney coordinator) |

| Prompt for early initiation | “Cause when you do the fistula you might as well go in straight for dialysis.” (HD patient with AVF) | ||

| Hope for alternatives | “My husband went to buy all these Indian herbs… He said it’s good for the kidney. But end up… he just use his own method.” (HD patient with catheter) | “They could still be holding on to certain hopes, for example, some of them, to quote patient, ‘I want to try traditional Chinese medicine,’ or ‘I want to try jamu.’ Jamu is a Malay kind of traditional medicine.” (kidney coordinator) | |

| Social Influences | |||

| Hearsay | “A lot of people will give you a lot of ideas, they will say don't go for dialysis you will die faster. When you do dialysis your heart will stop. A lot of things and they will say go for herbal treatment this and that.” (HD patient with AVF) | “So he’ll think that… by listening to all those people in the market saying hoo-ha about it, you can be cured.” | “They are very afraid because [there is] a lot of hearsay that dialysis is very costly like three, four thousand dollars. A bit exaggerated.” (kidney nurse) |

| Family involvement | Because she [wife] also encouraged me to create the fistula. She told me I have to face it sooner or later.” (CKD4 patient) “My husband also keep on telling me not to do it [AVF creation]. He said there is another way to do….” (HD patient with catheter) “Of course my family they said just try to hold on [preparing for dialysis], don’t do it so fast.” (CKD4 patient) |

“But once we bring this question up he [the patient] will be very resistant. That means he doesn’t want. It’s like we cannot go on to the next step to discuss which type of dialysis modality already. I don’t know also. I don’t know what he’s thinking in his own world. This has been happening more recently… I don’t know what’s in his mind. Maybe it’s his character?” |

“They want the support from the family members also. Like maybe they are concerned that let’s say they’re on dialysis and there’s no one to really take care of them. So, so they… they want to hear from their family members. Especially those who are very close with their family members. So when they really encourage them I think the patients will actually listen to them.” (kidney coordinator) “Get the significant others on board, and not just sit there in the clinic, but also, I mean, they are also heavily influenced by friends, so get them, or people they are close with… get them to see what’s going on.” (kidney doctor) |

| Experiences of others | “Because I have a friend with kidney failure and has a hole here [neck]. After the hole here, they do the leg and after that they do the fistula. Very painful right, three, four times, why not…just one time only do here just standby. Instead of three painful, you just one painful [sic].” (HD patient with AVF) “Like my brother-in-law, he dialyzed for about 3 years and he started to have a lot of illness and were in and out of the hospital. It does not seem that dialysis is very good.” (HD patient with catheter) |

“I have a friend, her mum didn't want to go for dialysis, end up needed to insert the tube. The tube was infected so cannot dialyse immediately. Have to stay in the hospital for one whole month, after that then can dialyse. You see, it costs more like this.” | “They might have talked to their friends. Yeah, so if they happened to talk to someone who has a very bad experience on dialysis then they will be likely to listen to them….: (kidney coordinator) |

| Health Care Provider Interaction and Communication | |||

| Trust/mistrust | “They [doctors] have more confidence to tell you how serious your condition is. But we are not doctors, for us if you are still feeling well how can we believe what you say… I’m half believing and half doubting.” (HD patient with catheter) | [Interviewer: Why do you think the doctor suggested preparing early for AVF?]” I think you all doctors want to make money is it?” | “They may not be accepting because for renal coordinator to tell them…that you need dialysis soon and from doctor’s point to tell them is different. Yeah so sometimes they prefer to hear from the doctor to tell them that when they will need.” (kidney coordinator) |

| Interpersonal tension | “I talked back to him [doctor]. I said if you want to dialyze, you go dialyze yourself. They kept persuading me and I just scolded them. I felt alright, why do I need to go for dialysis? Many doctors refused to see me because of my attitude.” (HD patient with catheter) | “It’s no problem to create the fistula, but don’t keep telling the patient that they have to create the fistula. He said he don’t want to come next time to see the doctor….” | “Some of them are quite hostile, they come in they said, ‘Why must I talk to you? Why must I waste my time talking to you? I’m alright.’ I quote, some of them they said, ‘I’m alright, I can work, I can eat, I can do whatever.’” (kidney coordinator) |

| Lack of clarity on access information | “You should ask the doctor to explain clearly. You cannot say the blood toxic level is too high, you got 900. You need to explain this 900, if you don't go for dialysis then what will happen this and that. You also never explain.” (HD patient with AVF) “I didn’t know at all that I needed to go for surgery… previously I knew that I needed to go for dialysis, my kidney failed but I didn’t know about the fistula surgery… the doctor didn’t tell me anything, no elaboration, no explanation.” (CKD4 patient) |

“Most important part is…on one hand is the patient’s acceptance. Acceptance depends on the patient’s knowledge, education background and…again whether the patient [has] symptoms or not.” (kidney doctor) “What might help in my opinion might be perhaps to clear this concept of dialysis. What does it entail if we have a guided tour if we have a patient to share about [dialysis]? How good it would be if I can prepare earlier.” (social worker) |

|

Abbreviations: AVF, arteriovenous fistula; CKD4, chronic kidney disease stage 4; HD, hemodialysis.

Figure 1.

Thematic schema.

These themes were common to all participant groups and characterized by subthemes to capture diversity of participant perspectives. Subthemes described by patients and family members focused predominantly on personal and interpersonal experiences, whereas subthemes described by health care providers additionally touched on processes and protocols related to predialysis education. These nuanced perspectives on subthemes are highlighted next.

Lack of Symptoms

The experience of symptoms was a dominant theme among all participant groups and appears to be fundamental in how patients make sense of their condition. Responsiveness and behavioral activation levels are linked to symptom experience and burden. As shared by all groups of participants, patients actively monitor and interpret their symptoms and report that they will know when they are sufficiently unwell to proceed with access preparation. Those with low symptom burden were unconvinced of the need for preparation because they could still carry out their normal day-to-day living without difficulties. Symptoms, if any, were normalized or not perceived severe enough to act on. Despite laboratory test results indicating declining estimated glomerular filtration rates, patients would report “feeling okay” and hence dismiss the need for AVF creation.

Dialysis Fears and Practical Concerns

Dialysis fears and practical concerns was also a dominant theme among all participant groups. Patients’ accounts focused on cost of treatment, dialysis-related lifestyle disruptions, and the impact on work ability or prospects. The difficulty accommodating dialysis into personal, work, and family life and daily routine was noted. Work was important not only as a source of income but also as a source of identity and means of fulfilling responsibilities toward family. Aside from these concerns, patients’ accounts were dominated by intense fear. For many, dialysis engenders fear related to their own mortality. Dialysis was described often in catastrophic terms, equating it to the end of life and prolonged suffering: “Dialysis no cure, dialysis just waiting to die only” (HD patient with AVF). Less common was fear of pain related to needles. Patients also reported fear of being a burden to their family. This concern transcended both the emotional dread and the practical dialysis concerns.

Family members also shared concerns over the anticipated lifestyle changes related to dialysis and highlighted the impact both on the patient and on themselves. The anticipated losses of time and resources (be it work or income) and the need to provide care acted as deterrents toward them supporting dialysis preparation and timely access creation.

Health care providers were cognizant of the concerns related to dialysis. They further noted how the general fear of dialysis is linked to dialysis stigma, which in turn acts as a barrier for clinicians tasked with initiating KRT discussions, often resulting in patients defaulting appointments. “They don’t want to think maybe because of taboo. They feel that once they start thinking about this they will resign themselves to it” (social worker).

Evaluating Value Against Costs/Risks of Access Creation

Patients reported weighing the value against the costs of access creation. Although many acknowledged that the benefits are that it is safer, easier, and avoids emergency care, these were not prioritized over the perceived risks. Many reported fear of surgery, including being cut, pain, and potential complications. Concerns about the viability of the fistula were noted, including complications and failure. Albeit not as frequently endorsed, some shared concerns about being embarrassed by the fistula appearance and it being a prompt for earlier/unnecessary initiation onto dialysis. “Once you operate already, you must go [on] dialysis. Correct or not? So don’t operate, you can still don’t go [on] dialysis” (patient with CKD4).

Family members also shared concerns related to access, but their concerns were mainly focused on the operation and viability rather than body image or earlier initiation onto dialysis. Their viability concerns revolved around risks for fistula blockage if not used or when engaging in activities (eg, sleep) that could compress the site. They were hence hesitant to support access creation because this would require extra care in everyday activities both for the patient and themselves. Health care providers noted that as with all procedures, there is a probability of failed fistulas. However, in their experience, although patients may have viability concerns, these are secondary to fear of dialysis. Fear surpasses any of the access concerns that patients or family may have about access and related procedures. They remarked that when or if patients’ fear of dialysis is overcome, their concerns related to access resolve or can be more easily addressed in the kidney care sessions.

Hope for Alternatives

It was common for patients and family members to turn to alternative treatments, such as Chinese or Malay traditional medicine, prayers, or holy water in the hope of sustaining kidney function and avoiding dialysis by achieving better outcomes when medicine could not. The preference to explore alternative options induces delay because both patients and family members put on hold any plans of decision related to KRT.

Preference for alternatives, albeit not endorsed in the process of formal care, was known to health care providers. They noted that traditional medicine was more readily accepted in the hopes of averting dialysis. This is driven by local practices and beliefs that traditional medicine is a less harmful alternative to medication and treatment.

Social Influences

Behavioral activation is susceptible to social influence in particular from family and friends and the experience of others. Social information can either hinder or facilitate dialysis preparation.

Hearsay

Hearsay, defined as information from sources that do not have a clear or credible origin, was often volunteered by family or friends. Notably, in all instances recounted, hearsay was negative, hence reinforcing fear and hindering timely access creation. Hearsay, as described by health care providers, caused patients to delay dialysis as they heard negative, and at times exaggerated, stories about costs and adverse outcomes from other people.

Family Involvement

Family advice was commonly sought but familial responses toward access varied. Some families urged patients to proceed with access creation to avoid the hassle of emergencies, whereas others advocated a delay due to dialysis concerns and fear. In some occasions, as shared by both patients and family member groups, patients chose to exclude family from discussion and the decision, in which case avoidance/denial or wait-and-see responses were dominant. Health care providers emphasized the importance of engaging with families, who in turn can help encourage patients to move toward dialysis access preparation.

Experiences of Others

Vicarious learning through the experiences of others, that is, witnessing or caring for family members or friends on dialysis, complemented hearsay or direct family input. Participants actively sought stories of “what life to expect on dialysis” and these shaped their orientation toward dialysis preparation. Others’ negative experiences seemed to outweigh health care provider advice, undermining confidence and reinforcing avoidance or delay of access creation. Conversely, for a few, such negative stories served as cue for action. Positive experiences that others had increased confidence about dialysis and AVF operation.

Health Care Provider Interaction and Communication

Health care interaction and communication was a dominant theme among all participant groups. Patients and family members focused mainly on the interpersonal climate and experience of trust in those key exchanges with health care providers. It was evident in both patient and family member accounts that health care providers are potentially key influencers, but their recommendations elicited different responses depending on interpersonal climate and trust.

Trust/Mistrust

Both trust and mistrust were voiced by patients and family members. Mistrust toward health care providers, when noted, appeared to be often reinforced by personal, family, or vicarious experiences of failed fistulas and appeared to hinder progress toward access. In contrast, trust of the health care provider or team of health care providers helped override dialysis concerns and fear. Interpersonal and communication aspects were linked to patients’ and family members’ experience.

Health care providers did not specifically discuss trust but commented that patients and family members appeared more receptive toward physicians and less trustful or open to advice from other kidney health care providers.

Interpersonal Tension

Behavioral activation toward dialysis preparation can be hindered by interpersonal tension during consultations and health care interactions. Tension and communication breakdown was noted across different parties (ie, health care provider–patient and health care provider–family). The tension typically arose from the provision of blunt and unsolicited advice by health care providers. Persistent advice, albeit well intended, before the patients and/or family members had come to terms with the need for dialysis triggered fear and avoidance. Ensuing responses by patients included hostility, dismissiveness, or failing to attend follow-up appointments. Family members noted that patients may be reluctant to return for follow-up appointments due to pressure from health care providers to make KRT plans and worry of being reprimanded for not committing to decision or delaying.

Lack of Clarity on Access Information

Despite KRT counseling, insufficient or lack of clarity about information was still evident. Many patients and family members reported being unaware of the value of access creation or having a limited understanding of their disease and KRT options and access procedures. Such gaps deter behavioral activation toward dialysis.

Health care providers acknowledged that at times patients may not fully comprehend or retain the information due to the increased load and the complexity and novelty of the content that is covered. Although these sessions are long enough to cover content, the longer duration may cause fatigue. Some noted that perhaps this part of predialysis is introduced rather late, that is, stage 4 or 5, and that it may be better to introduce part of the content earlier to allow patients and families time to come to terms with the CKD journey including ESKD.

Discussion

The present study triangulated the perspectives of patients, family care partners, and health care providers to examine barriers to timely access creation and optimal initiation of dialysis. As shown in prior work, the delay in AVF creation is mostly intentional rather than due to system/referral or provider delay.12,13,16,19 Despite early referral and access to kidney care and predialysis education, behavioral activation toward dialysis preparation is variable. All patients had attended kidney counseling sessions, yet few reported active intention and plans toward dialysis preparation. Most were oscillating between hesitation and ambivalence (wait and see) and disengagement manifested as denial of severity of their condition, avoidance of issue, or direct confrontation of providers’ recommendations. This suggests that existing pathways fail to sufficiently promote engagement and help patients begin planning.

This study identified perceptual and emotional barriers that are potentially amenable to change. Key is the lack of symptoms and mismatch between biomarkers of kidney function decline/severity (ie, low estimated glomerular filtration rate) and patients’ symptomatic experience. While symptoms are powerful internal triggers for help-seeking behavior, CKD remains asymptomatic until severe stages and there is marked interindividual variability in the course and severity of symptoms.29 When symptom burden is low or has no noticeable impact on functioning, patients readily dismiss the need to act toward dialysis. Even if symptoms are present, they may be too vague and generic (eg, fatigue) or not disruptive enough to cause alarm and action.30 Symptoms may also not be reported due to fear of being hastened onto dialysis, inadequate knowledge, or misattribution to other causes (eg, old age).31 There is a need for more effective education strategies to reconcile the discrepancy between symptomatic experiences and kidney function markers. Active visualization using dynamic representations such as animations or computer modeling may be promising tools to portray kidney function decline, its effects on other body functions, or access creation. Such visual interventions have been proven superior to traditional counseling or simple visual aids in other patient populations and may hence be well suited for predialysis education.32

The discrepancies between the content of predialysis education and the priorities of patients and their families are noteworthy. We found that the information needs and priorities of patients and their families diverge from those of health care providers.33,34 Patients and families were concerned about the trade-offs of dialysis in terms of costs, lifestyle/employability, and family burden, which fueled delay in dialysis plans.20,33,35 They were also deterred by concerns of surgery or the experience or stories of failed fistulas.23 They valued and sought information on the practical aspects and the subjective experience of life on dialysis, yet the content of classic predialysis education does not meet these needs. Predialysis education remains skewed toward provider-led biomedical-centric information about dialysis modalities with less attention to its psychological experiences.25

Study findings revealed unmet emotional needs and low emotional preparedness for dialysis. Fear was commonly cited. It often stems from the overcatastrophizing and maladaptive views of dialysis that far exceed negative perceptions, as noted in prior work.20,25 Dialysis, once considered a life-saving treatment with patients competing for access to dialysis programs, is now viewed as “suffering” and “end of meaningful life,” triggering intense and exaggerated emotions. In this context, safety-seeking behaviors such as avoidance and delay are likely to be negatively reinforced. These beliefs, albeit modifiable, seem to persist despite exposure to predialysis education.

More importantly, the effectiveness of educational efforts is questionable as information awareness remains low.36, 37, 38 Although all respondents in patient groups had been in kidney care for more than 2 years and attended at least 2 kidney coordinator sessions and hence were well exposed to extensive health information, they were not only emotionally unprepared but also not uniformly well informed. Many participants reported limited understanding and lack of clarity on information related to access and dialysis. Some reported that key information had not been communicated to them and did not recall benefits related to permanent access, although this was delivered as standard predialysis education content.

Poor recall and misunderstandings may be related to information and emotional overload. The intense emotional arousal, that is, fear, may lead to increased attention focus on the negative parts of information and potential threats (eg, AVF complications). Fear may also compromise working memory and information recall.39,40 Patients may also feel overwhelmed by the amount of information to the extent that they may disengage or have difficulties retaining and processing information. Given the cognitive impairment associated with CKD,41,42 more effective and streamlined ways of delivering information are needed. More emphasis should also be placed on emotional preparedness interventions. The ample evidence on the value of psychological preparation interventions in other contexts such as surgery would support adopting similar approaches in the context of dialysis preparation.43

Last, while concerns and fear toward dialysis were expressed, for some participants these faded away as a result of strong family support, positive peer influence, and trust in health care providers. It may be useful to consider how to best leverage these parties to motivate patients to start planning at earlier stages. First, professional input should expand beyond education and advice giving. Although these approaches are the backbone of health care,44 they may backfire when the focus is solely on advocating treatment while undervaluing personal costs or emotional concerns.45, 46, 47 As shared by health care providers, their efforts to coerce action or persuade are often met with resistance or disengagement.48 Interactions may become tension filled and adversarial, resulting in mistrust and pushback with regard to dialysis.24,25 There is thus a need to move away from a 1-size-fits-all educational approach whereby information is provided in a convenient standardized but potentially ineffective format. Dialysis preparation is a process rather than an event and care pathways should better align with individual (information and emotional) needs and levels of behavioral activation. It is difficult to pinpoint the optimal content, intensity, or mode of delivery. This study’s findings resonate with the concept of ongoing decision-support care, with lay input as opposed to discrete time-limited session(s). Earlier initiation of predialysis education to allow progressive exposure to ESKD information ahead of deteriorating kidney health, alongside discussion of values and preferences or concerns, may help ease psychological discomfort, as suggested by research on cognitive behavior therapy and exposure-based approaches.49 Given the dominance of financial concerns among patients and families, advanced planning related to financial matters may be a good starting point for such discussions.

Second, because peer influences are often as important as health care providers’ input,23,50 opportunities to incorporate peer learning in the context of predialysis education should be pursued.51 To this end, patient narrative resources, which carefully balance positive stories with challenges, may be particularly pertinent. Experimental studies in the general population have shown that peer stories weigh more heavily in dialysis modality decisions than physician’ recommendations.52 When portraying living well on dialysis, it is important to not make light of the life-changing experience or invalidate emotional concerns, but to challenge the maladaptive negative stereotypes. These can serve to both complement education and boost emotional preparedness for dialysis.

Last, findings suggest that families should be invited to be proactively involved so that their concerns can be addressed and they can then be enlisted as advocates for timely access creation and overcoming medical mistrust.

Study limitations should be noted. A convenience sample rather than a probability-based sample was used, which may limit generalizability. The ethnically diverse sample is one of the largest recruited to date and represents fairly well the national registry, yet sampling and self-selection biases cannot be ruled out. Patients not fluent in English, Chinese, or Malay were excluded. It is also possible that those who declined participation may have different perspectives on access creation. In addition, given the small sample size, differences in the perspectives of various health care provider types were not examined. Perspectives of physicians and coordinators could differ. Replication in other settings and wider samples of health care providers is warranted.

In conclusion, study findings showed that making the decision for timely AVF creation is a complex process that needs to be supported by efforts that go beyond information provision and education. Perceptual and emotional barriers need to be addressed to shift patients from avoidance and delay to timely access creation. The active involvement of health care providers, family, and peers earlier in the process may facilitate this process. These findings set the stage for interventions adjunct to kidney care to promote timely decision making and smooth transition onto KRT.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Konstadina Griva, PhD, Pei Shing Seow, BSocSci, Terina Ying-Ying Seow, MRCP, Zhong Sheng Goh, BSocSci, Jason Chon Jun Choo, MRCP, Marjorie Foo, FRCP, and Stanton Newman, PhD.

Authors’ Contributions

Research conceptualization and study design: KG, TY-YS; data acquisition: PSS, ZSG, KG; data analyses/interpretation: KG, PSS, ZSG; supervision or mentorship: KG, TY-YS, JCJC, MF, SN. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

This study is supported by National Medical Research Council Health Services Research grant (NMRC/HSRG/0058/2016). The funding source had no role in the study design or intervention; recruitment of patients; data collection, analysis, or interpretation of the results; writing of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Tonia Griva, health care professionals in the participating sites, and all study participants for support in this study.

Data Sharing Statement

The data generated and analyzed are not available publicly but are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Peer Review

Received April 4, 2019. Evaluated by 3 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from an Associate Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form October 19, 2019.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Supplementary Material File (PDF)

Item S1: English language interview guide.

Table S1: Characteristics of nonpatient participants.

Supplementary Material

Item S1. English language interview guide.

Table S1. Characteristics of nonpatient participants

References

- 1.Eckardt K.U., Coresh J., Devuyst O. Evolving importance of kidney disease: from subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet. 2013;382(9887):158–169. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendelssohn D.C., Curtis B., Yeates K. Suboptimal initiation of dialysis with and without early referral to a nephrologist. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(9):2959–2965. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teo B.W., Ma V., Xu H., Li J., Lee E.J. Profile of hospitalisation and death in the first year after diagnosis of end-stage renal disease in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39(2):79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomes A., Schmidt R., Wish J. Re-envisioning fistula first in a patient-centered culture. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1791–1797. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03140313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravani P., Palmer S.C., Oliver M.J. Associations between hemodialysis access type and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(3):465–473. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012070643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhingra R.K., Young E.W., Hulbert-Shearon T.E., Leavey S.F., Port F.K. Type of vascular access and mortality in U.S. hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2001;60(4):1443–1451. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polkinghorne K.R. Vascular access and all-cause mortality: a propensity score analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(2):477–486. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000109668.05157.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rastogi A., Linden A., Nissenson A.R. Disease management in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008;15(1):19–28. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solid C.A., Carlin C. Timing of arteriovenous fistula placement and Medicare costs during dialysis initiation. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:498–508. doi: 10.1159/000338518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arhuidese I.J., Orandi B.J., Nejim B., Malas M. Utilization, patency, and complications associated with vascular access for hemodialysis in the United States. J Vasc Surg. 2018;68(4):1166–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Renal Data System . USRDS; Bethesda, MD: 2018. 2018 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenz O., Sadhu S., Fornoni A., Asif A. Overutilization of central venous catheters in incident hemodialysis patients: reasons and potential resolution strategies. Semin Dial. 2006;19(6):543–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2006.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez-Vargas P.A., Craig J.C., Gallagher M.P. Barriers to timely arteriovenous fistula creation: a study of providers and patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(6):873–882. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buck J., Baker R., Cannaby A.M., Nicholson S., Peters J., Warwick G. Why do patients known to renal services still undergo urgent dialysis initiation? A cross-sectional survey. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:3240–3245. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhan V., Soroka S., Constantine C., Kiberd B.A. Barriers to access before initiation of hemodialysis: a single-center review. Hemodial Int. 2007;11:349–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2007.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes S.A., Mendelssohn J.G., Tobe S.W., McFarlane P.A., Mendelssohn D.C. Factors associated with suboptimal initiation of dialysis despite early nephrologist referral. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(2):392–397. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon H.E., Chung S., Chung H.W. Status of initiating pattern of hemodialysis: a multi-center study. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24(suppl 1):S102–S108. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.S1.S102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donca I.Z., Wish J.B. Systemic barriers to optimal hemodialysis access. Semin Nephrol. 2012;32(6):519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xi W., MacNab J., Lok C.E. Who should be referred for a fistula? A survey of nephrologists. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(8):2644–2651. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casey J.R., Hanson C.S., Winkelmayer W.C. Patients’ perspectives on hemodialysis vascular access: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(6):937–953. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Hare A.M., Batten A., Burrows N.R. Trajectories of kidney function decline in the 2 years before initiation of long-term dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(4):513–522. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberti J., Cummings A., Myall M. Work of being an adult patient with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Open. 2018;8(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xi W., Harwood L., Diamant M.J. Patient attitudes towards the arteriovenous fistula: a qualitative study on vascular access decision making. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(10):3302–3308. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussain J.A., Flemming K., Murtagh F.E.M., Johnson M.J. Patient and health care professional decision-making to commence and withdraw from renal dialysis: a systematic review of qualitative research. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(7):1201–1215. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11091114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harwood L., Clark A.M. Understanding pre-dialysis modality decision-making: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(1):109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tong A., Craig J.C., Nagler E.V. Composing a new song for trials: the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology (SONG) initiative. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:1963–1966. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creswell J. Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. SAGE Publications; Los Angeles: 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dousdampanis P., Trigka K., Fourtounas C. Diagnosis and management of chronic kidney disease in the elderly: a field of ongoing debate. Aging Dis. 2012;3(5):360–372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown S.A., Tyrer F.C., Clarke A.L. Symptom burden in patients with chronic kidney disease not requiring renal replacement therapy. Clin Kidney J. 2017;10(6):788–796. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfx057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pugh-Clarke K., Read S.C., Sim J. Symptom experience in non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease: a qualitative descriptive study. J Ren Care. 2017;43(4):197–208. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones A.S.K., Petrie K.J. I can see clearly now: using active visualisation to improve adherence to ART and PrEP. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(2):335–340. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1611-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urquhart-Secord R., Craig J.C., Hemmelgarn B. Patient and caregiver priorities for outcomes in hemodialysis: an international nominal group technique study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(3):444–454. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henry S.L., Munoz-Plaza C., Garcia Delgadillo J., Mihara N.K., Rutkowski M.P. Patient perspectives on the optimal start of renal replacement therapy. J Ren Care. 2017;43(3):143–155. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morton R.L., Devitt J., Howard K., Anderson K., Snelling P., Cass A. Patient views about treatment of stage 5 CKD: a qualitative analysis of semistructured interviews. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(3):431–440. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finkelstein F.O., Story K., Firanek C. Perceived knowledge among patients cared for by nephrologists about chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease therapies. Kidney Int. 2008;74(9):1178–1184. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright J.A., Wallston K.A., Elasy T.A., Ikizler T.A., Cavanaugh K.L. Development and results of a kidney disease knowledge survey given to patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(3):387–395. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song M.K., Lin F.C., Gilet C.A., Arnold R.M., Bridgman J.C., Ward S.E. Patient perspectives on informed decision-making surrounding dialysis initiation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(11):2815–2823. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Figueira J.S.B., Oliveira L., Pereira M.G. An unpleasant emotional state reduces working memory capacity: electrophysiological evidence. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2017;12(6):984–992. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsx030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tugade M.M., Fredrickson B.L., Barrett L.F. Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. J Person. 2004;72:1161–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berger I., Wu S., Masson P. Cognition in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2016;14:206. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0745-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Etgen T., Chonchol M., Frstl H., Sander D. Chronic kidney disease and cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35(5):474–482. doi: 10.1159/000338135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powell R., Bruce J., Johnston M. Psychological preparation and postoperative outcomes for adults undergoing surgery under general anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;5 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008646.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martino S. Motivational interviewing to engage patients in chronic kidney disease management. Blood Purif. 2011;31(1-3):77–81. doi: 10.1159/000321835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fisher S. Meeting Between Experts: An Approach to Sharing Ideas in Medical Consultations (Book) Sociol Health Illn. 1987;9(2):211–213. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rollnick S., Kinnersley P., Stott N. Methods of helping patients with behaviour change. BMJ. 1993;307(6897):188–190. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6897.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lederer S., Fischer M.J., Gordon H.S., Wadhwa A., Popli S., Gordon E.J. Barriers to effective communication between veterans with chronic kidney disease and their healthcare providers. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8:766–771. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller W.R., Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2012. The effects of brief mindfulness intervention on acute pain experience: an examination of individual difference; pp. 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- 49.von Knorring L., Lundberg V.A., Beckman V. Treatment of anxiety disorders: a systematic review. Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU). 2005. http://www.sbu.se/en/publications/sbu-assesses/treatment-of-anxiety-disorders2/

- 50.Griva K., Li Z.H., Lai A.Y., Choong M.C., Foo M.W.Y. Perspectives of patients, families, and health care professionals on decision-making about dialysis modality-the good, the bad, and the misunderstandings! Perit Dial Int. 2013;33(3):280–289. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2011.00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dennis C.L. Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40(3):321–332. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(02)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winterbottom A.E., Bekker H.L., Conner M., Mooney A.F. Patient stories about their dialysis experience biases others’ choices regardless of doctor’s advice: an experimental study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:325–331. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Item S1. English language interview guide.

Table S1. Characteristics of nonpatient participants