Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic there has been a reduction in hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction. This manuscript presents the analysis of Google Trends meta-data and shows a marked spike in search volume for chest pain that is strongly correlated with COVID-19 case numbers in the United States. This raises a concern that fear of contracting COVID-19 may be leading patients to self-triage using internet searches.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians worldwide have noted reductions in hospital admissions for emergencies including acute myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke.1 , 2 Several explanations have been proposed including reduced air pollution, changes in diet and lifestyle, or, most worryingly, avoidance of hospitals to reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection.3 There is significant concern that instead of presenting to hospital, fear of COVID-19 has led patients to self-triage using internet searches.

Google Trends™ is a free publicly available tool that monitors how often search items are queried over time and provides insights into public health behavior. Recommendations for the documentation of Google Trends™ analyses have previously been published4 and were consulted to facilitate reproducibility of the present study. We quantified searches in the United States (US) for the symptom of interest, chest pain, and the control terms toothache, abdominal pain, knee pain, heart attack, and stroke (time period Jan 1, 2017 to May 24, 2020, accessed May 28, 2020, no quotation marks, no combination symbols, all query categories). Data on the number of COVID-19 cases per day in the United States was retrieved from USAFacts.org, which collates data from government agencies and is used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Time-lag correlation analysis was performed using R. To assess the relationship between chest pain searches and COVID-19 caseload, data on search volume was also collected for the states with the highest and lowest numbers of COVID-19 cases. No extramural funding was used to support this work.

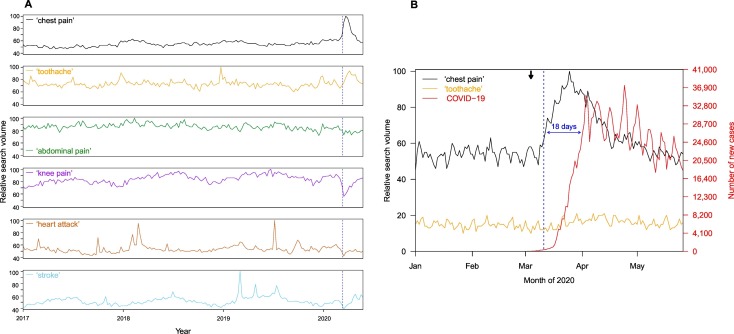

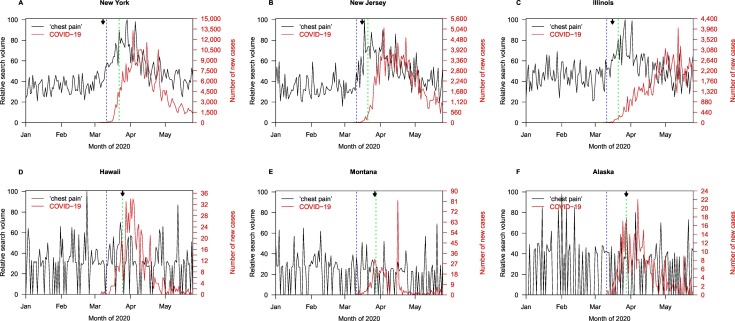

The number of cases of COVID-19 in the United States rose rapidly throughout March 2020 and during the same month the relative search frequency of the symptom chest pain, but not the control terms, nearly doubled compared to the previous 3 years (Figure 1A). There was a strong correlation between the number of new COVID-19 cases and Google search queries for chest pain (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.79 with 18-day time-lag) (Figure 1B). The search volume for chest pain also spiked in the states with the three highest (New York, New Jersey, Illinois), but not the three lowest (Hawaii, Montana, Alaska), COVID-19 caseloads (Figure 2 ).

Figure 1.

Relationship between internet search volume for ‘chest pain’ and new COVID-19 cases in the United States (US). A. Relative Google search volume for ‘chest pain’ and control terms ‘toothache’, ‘abdominal pain’, ‘knee pain’, ‘heart attack’ and ‘stroke’ from Jan 1, 2017 to May 24, 2020 in the United States. Blue dashed line: World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. B. Correlation between relative search volume for ‘chest pain’ and number of new COVID-19 cases per day in the United States (Pearson correlation 0.79 with 18-day time-lag). Time period: Jan 1 to May 26, 2020. Arrow: 100th cumulative case reached in the United States.

Figure 2.

Relationship between ‘chest pain’ search volume and new COVID-19 cases in the US states with the highest and lowest caseloads. Time period: Jan 1 to May 26, 2020. Blue line: World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Green line: stay-at-home order became effective in that state. Arrow: 100th cumulative case reached in that state. When search volume is below a critical value, this is registered by Google Trends™ as zero. A-C, US states with the three highest number of COVID-19 cases overall: New York, New Jersey and Illinois. D-F, US states with the three lowest number of COVID-19 cases overall: Hawaii, Montana and Alaska.

In this analysis we describe a strong correlation between the increase in COVID-19 cases and the utilization of Google for medical information. Chest pain is a common presenting symptom of life-threatening medical conditions including coronary artery disease, aortic dissection and pulmonary embolus, but is not a common symptom of COVID-19.5 The analysis presented here suggests that the rise in COVID-19 cases has led patients to seek medical information about their symptoms from the internet at substantially higher rates compared to the previous 3 years. This does not appear to be due to generally increased search volumes nor seasonal variation (Figure 1). Within the United States this was observed in states with a high prevalence of COVID-19 but not states with a low prevalence (Figure 2). This was despite all analyzed states instituting stay-at-home orders, which suggests this phenomenon is not related to lockdown restrictions. This raises a significant concern that in regions where caseloads are high, fear of contracting COVID-19 may be leading patients to self-triage, potentially in lieu of presenting to hospital. The rise in search volume for ‘chest pain’ but not ‘heart attack’ or ‘stroke’ may be explained by several hypotheses, including patients being more likely to search for symptoms rather than diagnoses, or it may reflect the reduced hospitalizations for these conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic and hence fewer patients receiving the diagnostic labels ‘heart attack’ and ‘stroke’. Indeed it was recently reported that the rate of catheter laboratory activation for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction has decreased by 38% in the United States compared to the pre-COVID-19 period,1 and there have been similar reductions in hospital presentations for other life-threatening conditions such as acute aortic dissection.6 This has been accompanied by a concurrent increase in out-of-hospital cardiac arrests7 and, amongst patients that did present to hospital with acute myocardial infarction, increased rates of delayed presentation and complications.8 While COVID-19 has a mortality of approximately 1%,9 acute myocardial infarction in the absence of contemporary treatment has a one-month mortality of up to 50%.10 As lockdown regulations begin to relax worldwide there is a significant risk of a second-wave of COVID-19, and so it is critical to re-emphasize to patients that internet searches are not an alternative to professional medical attention.

Footnotes

The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the manuscript, and its final contents.

References

- 1.Garcia S., Albaghdadi M.S., Meraj P.M. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(22):2871–2872. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diegoli H., Magalhaes P.S.C., Martins S.C.O. Decrease in hospital admissions for transient ischemic attack, mild, and moderate stroke during the COVID-19 Era. Stroke. 2020;51(8):2315–2321. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allahwala U.K., Denniss A.R., Zaman S. Cardiovascular Disease in the Post-COVID-19 Era - the Impending Tsunami? Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29(6):809–811. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nuti S.V., Wayda B., Ranasinghe I. The use of Google trends in health care research: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Hamamsy I., Brinster D.R., DeRose J.J. The COVID-19 pandemic and acute aortic dissections in New York: a matter of public health. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(2):227–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mountantonakis S.E., Saleh M., Coleman K. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and acute coronary syndrome hospitalizations during the COVID-19 surge. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.07.021. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Rosa S., Spaccarotella C., Basso C. Reduction of hospitalizations for myocardial infarction in Italy in the COVID-19 era. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(22):2083–2088. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambless L., Keil U., Dobson A. Population versus clinical view of case fatality from acute coronary heart disease: results from the WHO MONICA Project 1985-1990. Multinational MONItoring of Trends and Determinants in CArdiovascular Disease. Circulation. 1997;96(11):3849–3859. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.11.3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]