Abstract

Objective

To capture the perspective of prospective urology applicants experiencing unique challenges in the context of COVID-19.

Methods

A voluntary, anonymous survey was distributed online, assessing the impact of COVID-19 on a large sample of US medical students planning to apply to urology residencies. Themes of (1) specialty discernment, (2) alterations to medical education, and (3) the residency application process were explored.

Results

A total of 238 medical students, 87% third and fourth years, responded to the survey. While 85% indicated that the pandemic had not deterred their specialty choice, they noted substantial impacts on education, including 82% reporting decreased exposure to urology. Nearly half of students reported changes to required rotations and 35% reported changes to urology-specific rotations at their home institutions. Students shared concerns about suspending in-person experiences, including the impact on letters of recommendation (68% “very concerned) and program choice (73% “very concerned”). Looking to the possibility of virtual interactions, students identified the importance of small group and one-on-one communication with residents (83% “very important”) and opportunities to learn about hospital facilities (72% “very important”).

Conclusion

Despite the impacts of COVID-19 on medical education, prospective urology applicants appear to remain confident in their specialty choice. Students’ biggest concerns involve disruption of away rotations, including impacts on obtaining letters of recommendation and choosing a residency program.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in wide-reaching and unforeseeable changes to medical education. As a result of crucial health and safety precautions, medical students were temporarily removed from the clinical environment, resulting in delays and alterations of core requirements and specialty experiences. Students have been taking clinical subject exams remotely, and national licensing exams have been suspended. Changes will continue into the 2020-2021 residency application cycle, starting with the Coalition for Physician Accountability's recommendations against away rotations and in-person interviews.1 The Association of American Medical Colleges delayed the application deadline for the Electronic Residency Application Service. In addition, the Society of Academic Urologists converted to a coordinated interview offer process in the first week of November, with a delayed match date of February 1, 2021.

For medical students interested in applying to urology residencies, these changes present unique challenges. The American Urological Association match is consistently competitive and earlier in the year than the general National Resident Matching Program. Medical students have limited exposure to urology, as half of US schools provide no formal coursework in urology before third year.2 Historically, most prospective applicants have used their fourth year to complete multiple urology-specific rotations at different institutions, allowing students to gain additional exposure, confirm their interest in urology as a career choice, demonstrate geographic flexibility, and obtain letters of recommendation. In the current context, students’ in-person experiences will be restricted to their home institution with the possibility of virtual experiences at external programs. This new paradigm may make it more difficult for applicants to gain foundational knowledge and build strong relationships with urology faculty. Furthermore, with the applicant class yet undefined, it is difficult for programs to anticipate their priorities and interests.

These issues have been highlighted by commentary from residents and program directors.3 Kenisberg et al. used the most recent class as a proxy for these questions, finding that those who have already undergone the application process feel certain components cannot be replicated virtually.4 However, the issue remains that solutions and adaptations should consider the perspective of direct stakeholders, the 2020-2021 applicant class. We sought to capture their viewpoint through a survey-based questionnaire. We focused on how the pandemic has impacted 3 domains of the traditional student experience: (1) specialty discernment, (2) alterations to traditional medical education, and (3) the urology residency application process. We anticipate that such information may prove useful to urology training programs as rapid and widespread efforts are being made to develop new educational experiences and interactions with medical students interested in urology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A Google Forms survey was developed with medical student and program director oversight from 6 US urology residency programs. Survey questions were reviewed for content, quality, clarity, and effectiveness. Participation was anonymous and voluntary.

The survey consisted of 13 questions in multiple choice and Likert scale format, with 3 opportunities for free response comments. It elicited information on 3 domains of interest: (1) specialty discernment, (2) alterations to medical education, and (3) residency application process. The survey required participants to self-identify as medical students in the first question, closing the rest of the questions to those who selected “I am not a medical student.”

One question was in table format with a list of traditional curricular elements (required third-year core rotation, general surgery core rotation, urology rotation at home institution, urology rotation at other institution, USMLE Step 1 exam, USMLE Step 2 exam) and allowed students to select applicable alterations that they had experienced due to COVID-19 (canceled, altered from traditional form, postponed, not affected, unsure).

Three questions asked students to identify the level of priority of specific issues. Regarding changes to their curriculum and match process, the scale ranged from “not a concern,” “some concern,” to “very concerned.” For possible features of virtual interactions with programs, the range was “not important, “somewhat important,” to “very important.”

The survey was distributed by each of the 6 urology residency programs, utilizing a link through Urology Collaborative Online Video Didactics (COViD) evaluation form. COViD is a multi-institutional effort to provide lectures for residents during COVID that is hosted by the UCSF website.5 It provides an evaluation form for viewers to assess lectures. Viewers who completed an evaluation form and selected “medical student” as their evaluator demographics were then directed to our survey. This link was also shared via Twitter and the shared applicant Google spreadsheet. The link went live on May 3, 2020, and the survey was periodically retweeted over the following 7 days by the co-authors and regularly retweeted by members of the urologic community until it closed May 10, 2020. Individual responses were summarized with descriptive statistics. The survey received an exemption by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington.

RESULTS

A total of 238 medical students responded to the survey, the majority of which identified as third- or fourth-year students (87%, n = 214). Of all survey participants, there was a “definite applicant” subgroup of 172 students, consisting of third- or fourth-year students who responded that they were “definitely applying” to urology. An additional 18% (n = 43) chose “most likely applying.” Participants were geographically distributed as follows: South 32% (n = 76), Northeast 26% (n = 61), Midwest 23% (n = 54), West 17% (n = 40), and outside of the United States 3% (n = 7).

Specialty Discernment

Most students reported COVID-19 has had “no change” on their decision to apply to urology (86%, n = 201). Overall, 9% (n = 21) were “less likely to apply” to urology and 3% (n = 6) were “more likely to apply.” For students who reported being less likely to apply, the most common contributing factors were “inability to rotation at other institutions” (76%, n = 16) and “insufficient exposure to urology to be confident in specialty choice” (67%, n = 14). Students who were “more likely to apply” reported that they had additional time to learn about urology (50%, n = 3) and considered urology a traditionally high-earning specialty (50%, n = 3). An additional 3% (n = 6) reported planning to defer their application, citing the “inability to rotate at other institutions” (100%, n = 6) as well as the “inability to get letters of recommendation” (83%, n = 5).

In the subgroup of students “definitely applying to urology,” 93% (n = 163) reported no change due to COVID-19 and 3% (n = 5) reported they were less likely to apply. In contrast, for those that selected any levels of certainty below “definitely applying” (n = 60), a higher portion (27%, n = 16) reported they were “less likely to apply to urology” due to COVID-19.

Alterations to Medical Education

Of the 238 participants, 82% (n = 195) stated that the COVID-19 pandemic has reduced opportunities for exposure to urology, 16% (n = 37) described no change, and 3% (n = 6) reported more opportunities. Almost half of students reported alteration in format or duration of a required third-year rotation (48%, n = 114), and 16% (n = 39) identified changes to their required general surgery rotation (Fig. 1 ). Students reported that 35% (n = 83) of home urology rotations had been postponed and 32% (n = 77) reported no changes to those rotations. At the time of the survey, 82% (n = 196) of respondents reported away urology rotations had either already been cancelled (42%, n = 101) or were unsure of their status (40%, n = 95). The USMLE Step 1 exam was largely unaffected for the students completing the survey with 85% (n = 202) reporting no impacts from COVID-19. However, 39% (n = 93) have had Step 2 postponed and an additional 26% (n = 63) were unsure about their testing status.

Figure 1.

Alterations to medical education as a result of COVID-19 (n = 238).

Students were most likely to report being very concerned regarding “fewer opportunities to obtain meaningful letters of recommendation” (68%, n = 161), “fewer opportunities to see urologic procedures and surgeries” (55%, n = 131), and “fewer opportunities to interact with urology patients” (48%, n = 115; Fig. 2 ). Less than 12% of students designated each of these three categories as “not a concern.” In contrast, a majority of students were not concerned about the impact on their decision to pursue urology (61%, n = 144) or changes in grading systems (50%, n = 119).

Figure 2.

Medical student concerns about alterations to medical education as a result of COVID-19 (n = 238).

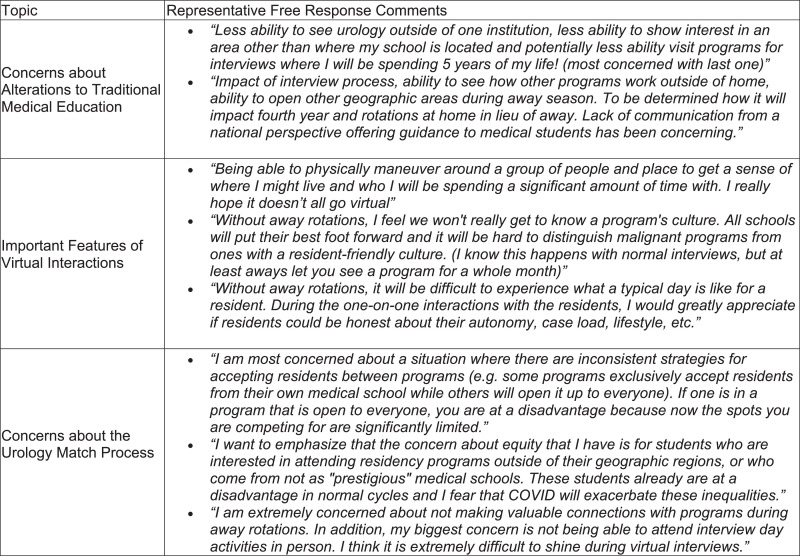

There were 43 comments identifying areas that participants felt were not addressed in the closed-ended options (Fig. 4). The most common themes centered on (1) the desire for in-person away rotations (21 comments), (2) concern regarding programs’ evaluation of applicants and perception of applicants’ interest (10 comments), and (3) concern about ability to build relationships with programs (10 comments).

Figure 4.

Representative medical student comments by topic.

Residency Application Process

Most respondents reported having a urology program at their home institution (87%, n = 207). Of those with a home program, roughly half responded that their home program had discussed the possible logistical changes to away rotations, the interview process, and match in the 2020-2021 cycle (46%, n = 207) while half had not discussed these potential changes (42%, n = 99).

When asked what features of away rotations and interview experiences would be most valuable to include, students designated one-on-one or small group interactions with residents (83%, n = 197) and faculty (69%, n = 165), and learning more about the hospitals and facilities (72%, n = 171) as very important (Fig. 3 ). For the subgroup of third- and fourth-year students who are “definitely applying” (n = 172), these priorities were even stronger, designating resident and faculty interactions as very important at rates of 88% (n = 151) and 73% (n = 126) respectively. Students also reported interest in opportunities to learn more about the city (49%, n = 116) and to get letters of recommendation from external institutions (61%, n = 144). There was the least enthusiasm about joining virtual clinics, with 27% (n = 81) of students overall and 37% (n = 63) of the definite applicant subgroup stating this was “not important.” This question acquired 24 free responses (Fig. 4 ). Common themes were (1) a desire for insights into the program culture, including meeting residents (10 comments), (2) experience of daily operations including scheduling and case volumes (6 comments), and (3) students’ desire to demonstrate their own abilities (4 comments).

Figure 3.

Features of virtual interactions important to medical students interested in urology (n = 238).

Last, students were asked to identify their concerns about the urology match process. The largest concern was “Program choice: I am concerned that inability to complete away rotations will make it more difficult to learn about different programs” (73% “very concerned,” n = 174). A high percentage of those responses came from definite applicant subgroup, with 80% (n = 137) answering “very concerned” and rising to 97% (n = 166) when including “some concern” responses. Next, students were concerned about “Equity: I am concerned that differing policies in different schools and states will place some students at an advantage” (54% “very concerned”, n = 128). Of note, 64% of students overall and 80% of third- and fourth-year students who are definitely applying stated that specialty discernment was “not a concern.”

A total of 40 free response comments were shared in this section (Fig. 4). The most common theme was students’ concern regarding their ability to evaluate programs and build meaningful relationships with them (14 comments) followed by concern about feasibility of matching at an outside institution and demonstrating regional interest (12 comments). Students also expressed concern regarding residencies' changing application evaluation processes in this context and the possibility of creating greater inequities (9 comments).

DISCUSSION

The COVID-19 pandemic will have wide-ranging effects on the traditional urology residency application experience, and it is essential to recognize and learn from these changes. We sought to characterize applicants’ concerns through the administration of a student-focused survey. The results will both provide guidance moving forward and serve as a historical record of the impact of COVID-19 on urologic education.

While the number of students considering a career in urology at this point in time remains undefined, prior data suggest the average number of applicant registrations is 459.8, with 414.2 applicants ultimately submitting lists.6 Therefore, the response may represent approximately half of the applicants in the coming 2 cycles.

Specialty Discernment

Our findings suggest that COVID-19 has minimally impacted specialty discernment, with most participants indicating there was no change in their commitment to urology despite the pandemic. However, students who were less confident in urology overall were more likely to indicate that COVID-19 had negatively impacted their specialty choice.

These results are consistent with literature suggesting that while clinical rotations tend to have a positive impact on students’ consideration of that specialty, the rotations themselves do not often change students’ minds but more likely reinforce their opinions.7 However, other studies have shown possible influence of clerkship experience, for example, students with prior urology clerkship experience are more likely to consider a career in urology.8 It may be more important to target students who are less confident in urology in order to enhance specialty discernment. As a field, we may need to be prepared for fewer applicants to urology this year.

Impact on Medical Education

Decreased exposure to urology is potentially a major concern both for the logistics of students’ clinical rotation scheduling and for residency preparedness. With almost half of students reporting impacts on core rotations, scheduling for urology electives may be postponed or deprioritized. In addition, students’ return to the clinical setting will be variable, contingent upon state and institutional policies and local COVID-19 prevalence.

The vast majority of students reported decreased opportunity for exposure to urology. As a result, the average foundational knowledge and practical experience may be lower than in previous years, when students often received 3-4 months of urology-specific education through home and external rotations. In addition, effects on core rotations may require medical schools to decrease direct patient care graduation requirements, and lack of clinical experience may negatively impact students’ comfort in the clinical environment upon entry to residency.

Residency Application Process

Perhaps the most noticeable change caused by the pandemic is the restriction on in-person interactions, including during the residency application process. Students express significant concerns regarding the repercussions on subinternships, away rotations, and interviews.

The away rotation framework has contributed to foundational components of residency applications, including letters of recommendation, urology-specific grades, and demonstration of surgical skills and geographic preferences. Consequently, their absence raises concerns regarding how programs will assess applications and distinguish between applicants. Other changes such as implementation of pass/fail grading systems, limited access to USMLE Step 2, and de-emphasis of USMLE Step 1 scores will further modify students’ applications compared to previous years. As a result, students will need to prioritize well-crafted ERAS applications with effective communication of their strengths and interests, which may facilitate programs’ ability to conduct holistic evaluations.

Letters of recommendation, which have previously been identified as perhaps the most important selection criterion for urology programs, may be an area of particular concern.9 Due to COVID-19, students will rely heavily on letters from 1 institution, and any letters from external programs will be based on virtual interactions. While the SAU has decreased the required number of letters from 4 to 2, with only 1 from a urologist, this may not completely solve the problem. Rising fourth-years who have already completed most if not all of their core rotations may not have asked for letters from attendings outside of their intended specialty. Even as students identify letter writers in other specialties, some, such as the 16% who were not able to complete their general surgery core rotations, may still feel at a disadvantage. Last, students cannot anticipate how letters from other specialties will be evaluated. Considering these issues, students would benefit from increased communication or possible standardization of letters to enhance equity.

Apart from contributing to applications, in-person experiences permit students to explore their priorities for their future residencies. External programs may provide subspecialties, research emphases, practice styles, and hospital types not available at their home institution. As students share with their peers on the interview trail, they gain information about programs’ cultures organically by word-of-mouth. Data reliant on former applicants misses some of the changes of this year—for example, while city visits may have been inconsequential in prior years, their absence and inability to be replicated this year may have a larger impact.10 This survey confirms students’ apprehension about their own abilities to make informed decisions without in-person opportunities to directly compare programs.

In addressing student concerns, programs may remedy the lack of in-person interactions with opportunities for candid communication, specifically with residents. While prior research has suggested that applicants highly value time with residents, the magnitude of change for this cycle requires that we address the question again, specifically identifying the most preferable format of these interactions.9 Our findings suggest that small groups and one-on-one conversations will be most important. As students seek out their best “fit,” it will be essential to create environments where residents may speak freely and answer applicants’ questions. Students also indicated interest to learn more about the hospitals and facilities which may be accomplished with virtual tours and discussion of practical logistics.

Programs will be forced to find alternative means to communicate with applicants, making online content more important than ever. Some programs have already reached out to students with virtual town halls, information sessions, and social media accounts. It will be essential for programs to harness websites as accessible and stable sources of information to which students can refer, especially as students try to balance their schedules with frequent online sessions. Websites may highlight program strengths and speak to recognized student interests in faculty members and alumni fellowships.11

Limitations of this study include that distribution via the COViD lecture series and social media may have introduced a selection bias for interested applicants who have already sought out lectures and made professional connections on Twitter. The reference map for students’ demographics only included the continental United States. Participant demographics were self-reported. The evolving nature of the impact of COVID-19 on medical education means that changes have already occurred since the survey was distributed. For example, the survey was distributed prior to the Coalition for Physician Accountability's release of recommendations. Because there was no denominator, we cannot know the survey response rate. Nonetheless, the information in the survey is potentially valuable for divining students’ most acute concerns and providing insights into what they value most.

CONCLUSION

Medical education during a pandemic is a novel matter, presenting unanticipated challenges for both students and medical education programs. Programs must consider the perspective of those directly impacted, and our survey demonstrates widespread concerns regarding the absence of away rotations and in-person interactions. Open communication between students and programs will be an essential component for equitable and successful adaptions.

Footnotes

This work was initially gathered to inform the Society of Academic Urologists (SAU) Executive Committee as they made decisions related to alterations in external rotations, recruitment, interviews, and the residency match process for this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It was also used by several of the Virtual Sub-Internships in Urology SAU Working Groups to help create a guidebook.

References

- 1.The Coalition for Physician Accountability's Work Group on Medical Students in the Class of 2021 Moving Across Institutions for Post Graduate Training. Final report and recommendations for medical education institutions of LCME-accredited. 2020.Available at: http://www.nrmp.org/coalition-physician-accountability-documents.

- 2.Slaugenhoupt BL, Ogunyemi O, Giannopoulos M, et al. An update on the current status of medical student urology education in the United States. Urology. 2014;84:743–747. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabrielson AT, Kohn TP, Clifton MM. COVID-19 and the urology match: perspectives and a call to action. J Urol. 2020;204:17–19. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenigsberg AP, Khouri RK, Kuprasertkul A, et al. Urology residency applications in the COVID-19 era. Urology. 2020;143:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.05.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Chu C, de la Calle CM, et al. Multi-institutional collaborative resident education in the era of COVID-19. Urol Pract. 2020;6:425–433. doi: 10.1097/UPJ.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Urological Association This data is an average of 2016-2020. Urology Residency Match Statistics. Available at: https://www.auanet.org/education/auauniversity/for-residents/urology-and-specialty-matches/urology-match-results.

- 7.Maiorova T, Stevens F, Scherpbier A, et al. The impact of clerkships on students’ specialty preferences: what do undergraduates learn for their profession? Med Educ. 2008;42:554–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiles BB, Thompson JA, Griebling TL, Thurmon KL. Perception, knowledge, and interest of urologic surgery: a medical student survey. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:351. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1794-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissbart SJ, Stock JA, Wein AJ. Program directors’ criteria for selection into urology. J Urol. 2015;85:731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs JC, Guralnick ML, Sandlow JI, et al. Senior medical student opinions regarding the ideal urology interview day. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:878–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel BG, Gallo K, Cherullo EE, Chow AK. Content analysis of ACGME accredited urology program webpages. Urology. 2020;138:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2019.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]