Abstract

Cardiothoracic surgery will soon have a shortage of qualified surgeons in India, because the profession is losing appeal among surgical residents. Do we really understand why the profession is not their first choice, or what the current cardiothoracic residents think about their training? This article is the first nationwide survey meant only for cardiothoracic residents in training, conducted through online survey tool to report on the issues concerning our residents.

Keywords: Thoracic surgery, Residents, Cardiothoracic and vascular surgery

Introduction

Every cardiac surgeon recognizes that there will soon be a shortage of qualified cardiothoracic surgeons because the profession is losing appeal among surgical residents. But do we really understand why the profession is not their first choice, or what the current cardiothoracic residents think about their training? This article is the first nationwide survey to report on the issues concerning our residents.

Methods

The survey was meant for only cardiothoracic residents in training; a web link was emailed to individual residents or their program directors. It was conducted using the online survey tool, Survey Monkey (Survey monkey enterprise, Los Angeles, CA). The survey comprised of 7 sections with a total of 34 questions, covering demographics, training pathway, work life balance, academics and prospects, workplace environment, and a dedicated section for female residents. Where the answers required a statement the Likert scale (e.g., very satisfied, satisfied, neutral, dissatisfied and very dissatisfied) was employed. The survey was anonymous but covered details like age, gender, year of training, and training pathway.

Results

A total of 145 residents participated in the survey, 128 males and 17 females. One hundred and five out of 145 were answered all the questions.

Basic demographics

Out of the respondents, 28% were between the ages of 21 and 30, 52% between 31 and 39, and 20% were over the age of 40. One hundred six (73%) were married and out of them, 60 had children below the age of 18 years.

Training pathway

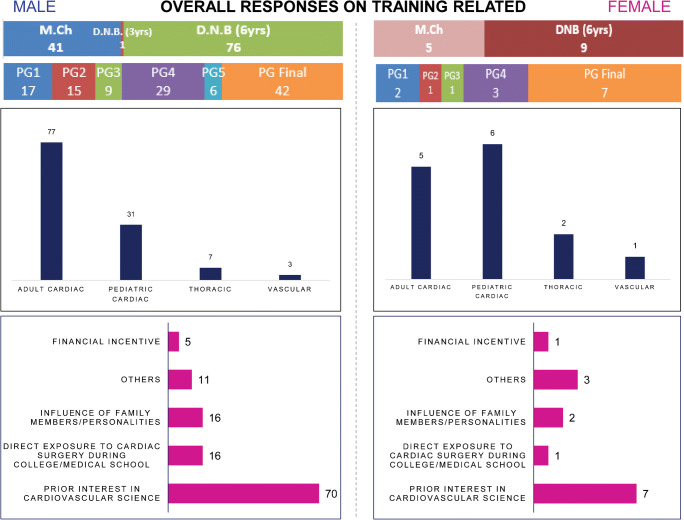

Seventy-six (52%) were from the National board of examination (NBE) 6-year cardiothoracic (CT) program, 41 (28%) were in the M.Ch (CT) program, and 1 respondent was from the NBE 3-year CT program. Forty-two (35%) were final year trainees, 41 (34%) were between 1st and 3rd years while the remaining 35(31%) were in the 4th and 5th years of training (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Showing (i) training pathway respondents, (ii) year of training, (iii) preferred career pathway for respondents, and (iv) reasons for choosing cardiac surgery. Similar results from female respondents are displayed on the left

Motivation and prospects

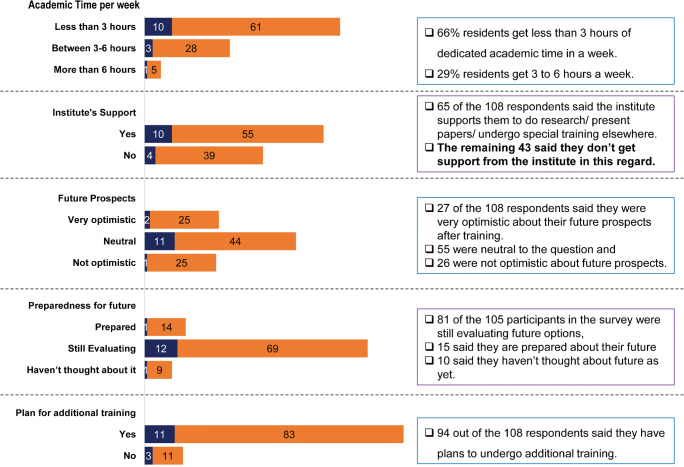

When asked about their future career paths, 77 (65%) chose adult cardiac surgery, 31 (26%) chose pediatric cardiac, and 10 (9%) decided on thoracic and vascular path. Seventy (48%) respondents said they joined the profession out of interest in the field of cardiac surgery, 16 (11%) said they had prior exposure to CT surgery, and 16 (11%) gave other reasons. When asked about their level of optimism towards their prospects, 27 of the 108 respondents said they were optimistic, while 55 chose to remain neutral and 26 were not optimistic. When asked about their preparedness for the future, 15 of the 105 respondents were prepared, 81 were still evaluating, and 10 have not started preparing. Eighty-seven percent of residents have claimed that they are not confident of independent practice and will choose to undergo additional training.

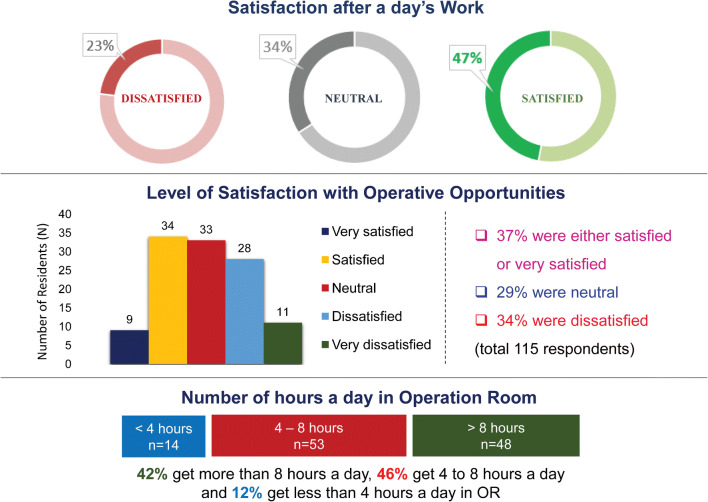

Work life balance

Forty-seven percent of residents said they were satisfied with their training, 23% were dissatisfied, while 34% chose to remain neutral. When specifically asked about their level satisfaction with their operating opportunities, 37% replied positively, 29% were neutral, and 34% replied negatively. Forty-two percent of residents said they spent more than 8 h a day in the operating room (OR), 46% spend between 4 and 8 h, while 12% spend less than 4 h in the OR (Fig. 2). Fifty-seven percent of residents claimed they are on call 1 in 3 days, 38% said they get between 1 in 3 and 1 in 6 on call duties per week, and the remaining get less than 1 in 6 calls per week. Eighty-one percent of the respondents claim they barely get leisure time while the remaining 19% claimed they get adequate leisure time.

Fig. 2.

The upper chart displaying level of satisfaction among residents, middle chart showing satisfaction with operative opportunities, and the lower part is showing hours spent in the operating room

Academics

Sixty-six percent of respondents said they get less than 3 h of dedicated academic sessions per week, 29% get between 3 and 6 h a week, while 5% get more than 6 h a week. When it comes to institutional support to present papers, perform research, or acquire special training, 65 of the 108 respondents replied positively (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Showing residents response to number of hours dedicated to (i) academics, (ii) response to institutes support towards research, paper presentation, and outside training, (iii), (iv), (v) showing their response to level of optimism towards the future, preparedness for the future, and their plan for additional training. Female responses are charted in blue

Training environment

Residents were asked the level of importance their program tracks their operative requirements, only 27% of respondents said their program actively tracks their operative requirements. Ninety percent of residents have a dedicated library at their institute, 58% of respondents have a dedicated on-call room, however, 54% of female residents claimed they did not have a dedicated on-call room. Ninety-three percent of the residents do not have a designated area for recreation or sports, and 61% of the residents claim their canteens fail to provide wholesome food.

Sixteen percent of the respondents claim that they have been used by faculty members to run personal errands; 53% also claim that they are engaged in more clerical than clinical work. Forty-four percent of the residents say they find it difficult to avail leave and only 54% of residents say they are respected and made to feel wanted by their faculty.

Female residents

There were a total of 14 female respondents. When asked if they feel their career would come in the way of their profession, 64% agreed, 36% were unsure, and 18% disagreed. Sixty-one percent of the respondents said they have no female role models, 27% did not see the need for one, and 15% said they have female role models. Regarding sexual harassment at the workplace, there were 13 respondents and only 1 claimed to have faced it (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Showing responses of female cardiac surgical trainees

Finally, when asked about their decision to take up cardiac surgery, sadly, only 59% replied positively, 19% resigned to treating it like any other profession, and 22% would change if they could.

Discussion

As the population ages, so does the burden of cardiovascular disease; unfortunately now, there is fall in the number of cardiothoracic surgeons entering the workforce, and by 2020, the USA is going to face an acute shortage of CT surgeons [1]. India already faces a shortage of cardiothoracic surgeons who perform between 70 and 80,000 heart surgeries a year but need to perform close to 5 million heart surgeries annually [2]. Up to 60% of the M.ch positions in CT surgery were left vacant last year; poor remuneration and long latency to reach financial independence were the reasons cited [3]. This is one of the reasons why the 6-year integrated program is becoming popular among medical students aspiring to become cardiac surgeons [4]. Lack of remuneration is a complex problem attached to the economics of the whole profession affecting multiple stakeholders, and its discussion would be futile. However, we need to address why cardiac surgery is not the first choice among surgical aspirants and why current trainees have a negative outlook towards their profession.

The results of this survey show that 75% of the respondents had a negative outlook to their future, 87% agreed that they are not confident of independent practice at the end of their training, and regrettably 41% were unhappy with their decision of taking up cardiac surgery. Even if you assume that only disgruntled residents will make the effort of venting out their frustrations through this survey, selection bias aside, it is still a significant number. This is a cry for help; we need to spend more time with our residents and understand how best we can help them.

A good role model can allay their fears of cardiac surgery and correct misconceptions of the specialty. Vaporciyan et al. reported that general surgical residents exposed to a mentor from cardiac surgery early into their training were more likely to join cardiac surgery [5]. We need a structured mentorship program to nurture current residents and guide them to their ultimate career goals. Mentors should identify their residents’ shortcomings and help work on them. The goal of every program director should be directed towards making their residents “job worthy” at the end of their training. In Salazar’s report, most US cardiac surgical residents claimed that the negative outlook of their program directors and their lack of involvement in getting them a job was one of the reasons for their disgruntlement with the profession [6]. We need to develop a systematic mentorship program and recruit cardiac surgeons who have the aptitude to foster trainees. The mentor along with his mentees should set realistic goals, assess the effectiveness of the training, and prepare for the future career. There needs to be a structured feedback system wherein both stakeholders can provide feedback about each other and rework on it. Mentors and mentees necessarily need not to belong to the same institution; the American College of Cardiology website allows mentors and mentees to register for a mentorship program, which then matches them based on their profiles. The website also provides resources to develop and monitor the program [7].

We need to engage medical students and general surgery residents early on, in order to attract the best and the brightest. Medical school students need to learn about cardiac surgery from practicing specialists and to clear popular misconceptions about the profession. Table 1 shows list of suggestions to improve satisfaction among residents and their quality of training. Interns and general surgery residents interested in cardiac surgery should undergo supervised rotations at busy cardiac surgery units, so that they get a good feel of the specialty and make an informed decision on their career. In their article, Preece et al. have showed that among surgical occupations, first year medical students showed the highest interest in cardiac surgery but this interest wanes in the final years, because of lack of engagement from the profession [8].

Table 1.

Listing suggestions to improve satisfaction among residents and their quality of training

| Early engagement with medical students and general surgery residents from cardiac surgery professionals | |

| Structured mentorship program for current residents | |

| Setting realistic goals from trainees at the beginning of their program. | |

| Modular training program to assess competency, progress, and aspiration | |

| Mandatory tracking of operative requirements | |

| Focus on making trainees job worthy by the end of their training |

In our survey, residents have expressed their displeasure with their training and academics. The current training pathways in India are broad based with little emphases on its effectiveness. Valooran and authors have suggestions for a modular training program which systematically trains and re-evaluates competency at various levels [9]. Based on these recommendations, the various academic boards need to revisit their guidelines and curriculum, for the training to become more relevant to current requirements and expectations.

This article has highlighted the disillusionment of residents in training, and the lack of attention from program directors or guides. Dr. Marc Orringer once said, “the lifeblood of every profession is the infusion to its ranks of youth”. The 6-year integrated program has worked well in addressing the shortage of CT residents both in India and in the USA [10]. Among the public, cardiac surgery still has an aura around it; sadly, this diminishes when it comes to our trainees. As stakeholders of this noble profession, it is our responsibility to ensure that the “best and brightest” make cardiac surgery their first choice. We need to engage aspirants at medical school and during general surgery, and we are obliged to support and guide our current residents.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Grover A, Gorman K, Dall TM, et al. Shortage of cardiothoracic surgeons is likely by 2020. Circulation. 2009;120:488–94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.The Indian Express Online Edition. Press release of Governor’s speech in National Cardiothoracic Surgery Conference. 2008. http://www.webcitation.org/6ErUM1Hr9. Accessed 04 Mar 2013.

- 3.Few takers for cardiothoracic surgery course alarming: Patil- The New Indian Express. http://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/bengaluru/2017/feb/24/few-takers-for-cardiothoracic-surgery-course-alarming-patil-1574109.html. Accessed 25 May 2018.

- 4.Vaithianathan R, Panneerselvam S. Emerging alternative model for cardiothoracic surgery training in India. Med Educ Online. 2013;18:1–4. doi: 10.3402/meo.v18i0.20961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaporciyan AA, Reed CE, Erikson C, Dill MJ, Carpenter AJ, Guleserian KJ, Merrill W. Factors affecting interest in cardiothoracic surgery: survey of North American general surgery residents. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salazar JD, Ermis P, Laudito A, Lee R, Wheatley GH, III, Paul S, Calhoon J. Cardiothoracic surgery resident education: update on resident recruitment and job placement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1160–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resources for Mentors. American College of Cardiology. https://www.acc.org/membership/member-benefits-and-resources/career-resources/mentoring-program. Accessed 11 Sep 2018.

- 8.Preece R, Ben-David E, Rasul S, Yatham S. Are we losing future talent? A national survey of UK medical student interest and perceptions of cardiothoracic surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2018;27:525–529. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivy119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valooran GJ, Sebastian R. Modular training in cardiothoracic residency—practical considerations to revive and streamline Indian training systems. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;33:361–368. doi: 10.1007/s12055-017-0595-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chikwe J, Brewer Z, Goldstone AB, Adams DH. Integrated thoracic residency program applicants: the best and the brightest? Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:1586–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.05.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]