Abstract

The aortic valve is the functional unit of cusp and root. Various geometrical and functional analyses for the aortic valve unit have been executed to understand normal valve configuration and improve aortic valve repair. Different concepts and procedures have then been proposed for reparative approach, and aortic valve repair is still not standardized like mitral valve repair. It has become apparent, however, that interpretation of the geometry of the aortic cusp and root and its appropriate application to operative strategy lead to creating a functioning aortic valve. Herein, the aortic valve geometry and its clinical implications are reviewed to provide information for the selection of appropriate operative strategies.

Keywords: Aortic valve repair, Aortic valve geometry, Cusp effective height

Introduction

Historically, heart valve repair started with procedures on the mitral valve in the form of closed commissurotomy for stenosis in 1920s. These first attempts appear crude compared with current standards; they were performed on the closed and beating heart, and echocardiography was not yet available. The first attempts at treating aortic regurgitation were also reparative operations on the closed heart [1]. It was only after the development of extracorporeal circulation and controlled cardiac arrest as basis for precise intracardiac procedures that mitral valve repair evolved further. In parallel to extracorporeal circulation, heart valve prostheses were developed. They revolutionized the treatment of heart valve disease being a very reproducible operation.

While valve replacement became a routine procedure, some surgeons persistently worked on improving reconstructive procedures, mainly for the mitral valve. In particular, Carpentier was one of the individuals who improved the quality of mitral valve repair by creating standardized procedures [2]. This was in effect facilitated by the fact that the mitral valve was a good substrate for repair and it proved to be relatively easy to assess its morphology and pathology. In particular, it has only two leaflets with one coaptation line; the classic water test has been a simple method of checking mitral valve form and function. Even though different annuloplasty devices were designed, reduction and stabilization of the mitral annulus proved to be comparatively easy for most pathologies. In 1990s and early 2000s, it became apparent that mitral valve repair resulted in a survival advantage over mitral valve replacement and was associated with a lower incidence of valve-related complications. Therefore, valve repair became the preferred treatment modality for mitral regurgitation.

Stimulated by the feasibility and clinical success of mitral valve repair, some surgeons started repairing the aortic valve, either for rheumatic regurgitation or insufficiency of the bicuspid valve [3, 4]. In addition, some surgeons were struck by the impression that the valve itself, i.e., cusps, was apparently normal in many instances of aortic dilation and concomitant regurgitation. They came to realize that normal aortic valve form depends not only on cusps, but also on root morphology; the aortic valve is the functional unit of cusp and root. This realization stimulated the hypothesis that normalization of root form should lead to normalization of aortic valve function. This was the common denominator of operations like sinotubular junction (STJ) remodeling, root remodeling, or valve reimplantation [5–7].

In the past 20 years, various geometrical and functional analyses for the aortic valve unit have been performed to understand normal valve configuration and improve aortic valve repair. There is increasing evidence that accurate interpretation of the geometry of the aortic cusp and root and its appropriate application in the operative strategy are important prerequisites to successful aortic valve repair. Herein, the current knowledge of aortic valve geometry and its clinical implications are reviewed.

Anatomy and nomenclature of the aortic valve

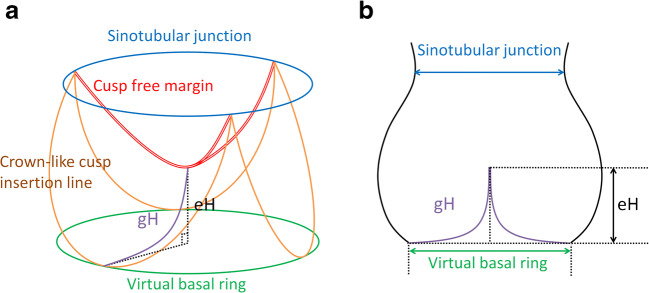

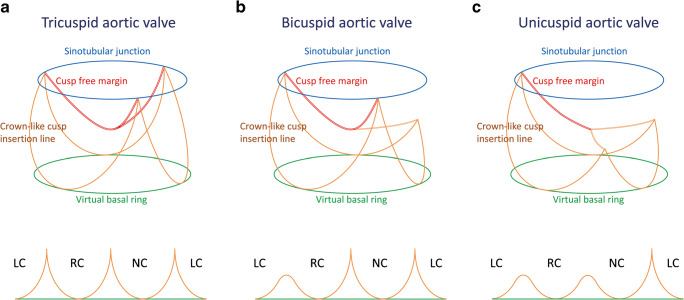

In simple terms, the aortic valve is a cylindrical structure extending from the left ventricle in which cusps are supported in crown-like fashion (Fig. 1a). This crown-like cusp insertion line is helpful to explain anatomical characteristics of the aortic valve. Each tip of the crown-like cusp insertion line is termed the commissure, and the STJ corresponds to the plane connecting the commissures. Importantly, the number of commissures of normal height defines cusp morphology; the tricuspid aortic valve has three commissures of normal height (Fig. 2a), the bicuspid aortic valve has two (Fig. 2b), and the unicuspid aortic valve has one or none (Fig. 2c). A lower commissure can be described as rudimentary and corresponding cusp apposition is fused at the various degrees. In the sinus of Valsalva, the crown-like cusp insertion line partitions aortic root wall into the coronary sinus and the intercusp triangle. The former is exposed to aortic pressure and the latter to left ventricular pressure.

Fig. 1.

Normal aortic valve configuration. a Diagrammatic representation. b Schematic drawing, modified from Schäfers 2013 [8]. (eH effective height, gH geometric height)

Fig. 2.

Diagrammatic representation of aortic valve morphology and schematic drawing of cusp insertion line, modified from Schäfers 2008 [9]. a Tricuspid aortic valve. b Bicuspid aortic valve. c Unicuspid aortic valve. (LC left coronary sinus, NC noncoronary sinus, RC right coronary sinus)

The lower part of the aortic root, namely the base of the aortic valve, could be considered as the annulus. The nomenclature for this part has been confusing in the surgical and cardiologic literature. It has been termed aortoventricular junction, i.e., transition of ventricular to aortic tissue [10]. Whereas it may be the case in some normal aortic valves [11, 12], this transition may be in the sinus portion of the root, especially in bicuspid and unicuspid aortic valves (submitted). This observation confirms the publication of Anderson who actually assumed that the aortoventricular junction is above the basal level of the valve in all three sinuses [10]. He also pointed out that the term “ring” is favorable to describe circles surrounding the crown-like cusp insertion line. Therefore, the best term for the basal circumference connecting cusp nadirs is probably the “virtual basal ring”, which is in line with echocardiographic terminology [13].

The clinical problem

Since aortic cusp and root repairs were invented as mentioned above, a number of groups attempted to reproduce these techniques. Over the next 10 years, it became apparent that these operations could produce an acceptable early result, but did not always normalize aortic valve function in a reproducible and durable fashion. Unfortunately, only a limited number of reports dealing with failed aortic valve repair appeared in the surgical literature at that time [14, 15]. Different possible causes of failure were proposed, but none analyzed both failures and successes in a systematic and geometric fashion. Duran attributed failures of his valve repairs to degeneration of the used material [14]. Cosgrove and coworkers related failures after reconstruction of regurgitant bicuspid aortic valves mainly to the used technique, e.g., triangular resection of cusp tissue [15].

A few reports also dealt with failed aortic root repair, but did not come up with conclusions that could have led to improved performance of these operations. Pethig and colleagues, who analyzed failures of the valve reimplantation, simply concluded that the level at which the valve was placed within the graft was essential [16]; they did not analyze valve form further.

This lack of clinical analysis may in retrospect have been related to limited knowledge on the normal geometry of the aortic valve. An experimental investigation on aortic valves by Swanson and Clark was one of the limited pieces of information in this field [17]. They studied five aortic homografts after pressurized fixation by silicone rubber and found relatively constant relationship between different dimensions of cusp and root. The investigation, however, did not generate an objective and quantitative parameter indicating the valve configuration. In addition, there was little interest in aortic valve repair at that time, and possibly, their information was simply overlooked subsequently.

Kunzelman and David noticed the importance of understanding normal valve configuration for aortic root repair and conducted an anatomic study on ten aortic homografts [18]. They also detected the geometrical relationship between cusp and root size and proposed ideal root size compatible with each cusp size. Whereas this research was meaningful as an operation-oriented study, their aim was limited to appropriate graft selection for the valve reimplantation and their all values were established on the assumption that all cusps should be geometrically normal.

Effective height

These investigations did not yet lead to better understanding of cusp and root as a functional unit based on objective and quantitative parameters. Intuitively, it seems apparent that the aortic cusps need not only a sufficient amount of tissue but also a particular form for their function.

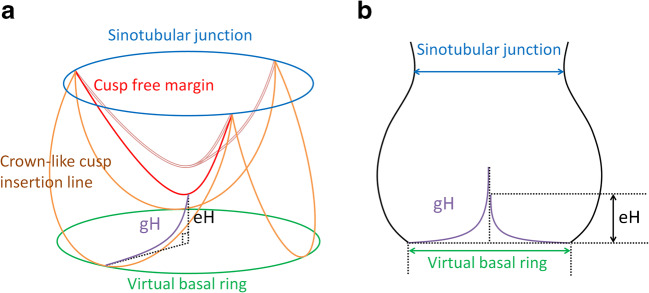

The first analysis that led to the development of a new configuration parameter was a clinical review of preserved or repaired bicuspid aortic valves in our own experience [19]. We observed failure with the need for reoperation in several patients after valve-sparing aortic root replacement. The common denominator of these valves was the presence of cusps with abnormally low height distance between the free margin in diastole and the basal plane (Fig. 3). Initially, this finding was not well understood. The clinical analysis then suggested that this decreased height distance—termed effective height (eH)—is an indicator of cusp prolapse (Figs. 1 and 3). The next patients who came for reoperation were treated by shortening of both cusp free margins, which led to elevation of eH and restored aortic valve function to normal. We thus hypothesized that eH could be used as an indicator of competent aortic valve function [20].

Fig. 3.

Prolapsed aortic valve configuration. a Diagrammatic representation. b Schematic drawing, modified from Schäfers 2013 [8]. (eH effective height; gH geometric height)

Available literatures did not indicate the normal range of eH at that time. Therefore, we initiated an investigation in which 130 volunteers with normal aortic valve function were studied by transthoracic echocardiography [21]. We found a close correlation between eH and aortic root size as well as patient size. In adult individuals with a mean body surface area of 1.8 to 2 m2, eH was almost in the range of 9 to 10 mm. This finding was recently confirmed by a recent anatomic study [22]. Determination of eH can be done by echocardiography to assess cusp configuration before and after repair; it has been entered into the echocardiographic recommendations for aortic valve assessment [23]. Moreover, a caliper was developed for the clinical scenario, which allows for intraoperative measurement of eH before and after repair and thus facilitates the decision making [20]. With this caliper, we define cusp prolapse as 40% or less of cusp geometric height (described in the next section) and perform central plication sutures on the cusp free margin or triangular resection in the presence of marked tissue redundancy until an appropriate eH is achieved.

Geometric height

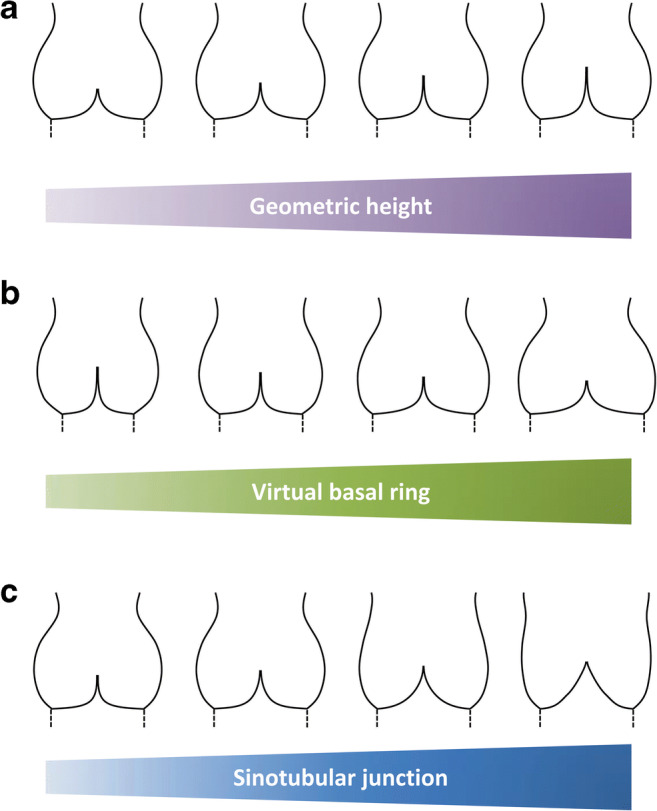

There were already basic considerations that eH would have to be related to the amount of cusp tissue (Fig. 4a) and the height of cusp tissue in the center of the cusp could be employed as an indicator of cusp size. In addition, clinical observations indicated limited reparability and suboptimal durability of valve repair in so-called restrictive cusps [27]. While most restrictive cusp pathologies can be expected to involve a certain degree of cusp shrinking, no objective or quantitative parameter was used to define cusps as restricted. We hypothesized that the height of cusp tissue could be used as a quantitative parameter to indicate the presence of restriction or retraction.

Fig. 4.

Correlation between aortic valve configuration and each geometrical determinant. a With different geometric height, modified from Marom 2013 [24]. b With different virtual basal ring diameter, modified from Marom 2013 [25]. c With different sinotubular junction diameter, modified from Marom 2013 [26]

A review of literatures yielded limited information for this issue, which did not appear conclusive [17, 18, 28–30]. We thus initiated a study in which we measured the cusp tissue height—termed geometric height (gH)—in 621 patients undergoing aortic valve repair (Figs. 1 and 3) [8]. In tricuspid aortic cusps, a mean gH was determined to be 20 mm; 24 mm for the nonfused cusp in bicuspid aortic valves. A recent anatomic study in normal tricuspid aortic valves confirmed a mean gH of 19 mm [22]. Using this data, we arbitrarily defined a gH of less than 80% of normal as retracted. This definition has been used in our decision-making process of pursuing with valve repair only if gH is normal. We usually proceed with valve repair if gH is at least 17 mm in tricuspid valves and 20 mm in bicuspid valves; otherwise, we will prefer to replace the valve.

Importance of annular dilation

It has frequently been stated that the annulus is important for aortic valve form and function, and this has been taken as an argument in favor of valve reimplantation approach or the combination of root remodeling with annuloplasty [31–33]. These statements, however, are not founded on clear facts. The normal values for annular dimension have never been clearly defined; in echocardiographic studies, annular diameters of up to 30 mm have been documented in healthy young individuals with normal aortic valve function [34].

In our own experience, a large annulus was indeed a predictor for postoperative valve failure in valve-sparing aortic root replacement [35]. Interestingly, this predictor was independent of the operative technique used (reimplantation or remodeling). We have also found that a large annulus was associated with large root dimension. One likely explanation for this finding is that normalization of large root dimension led to a higher incidence of postoperative cusp prolapse, at least if the operation was not guided by eH measurement. The negative effect could be neutralized by cusp plication and, therefore, the impact of annular dilation itself was not clarified in this study. Moreover, our recent observation complicates the matter of annular stabilization further since we found a reduction of annular diameter even through root remodeling without additional annuloplasty [36].

Nevertheless, the first clinical proof of the importance of annular dilation was maybe our group’s analysis of isolated bicuspid aortic repair [37]. Although cusps were repaired according to eH, more than 50% of the repairs failed within the first 5 to 7 years if there had been marked annular dilation at the time of surgery. The annular contribution to failure was confirmed by the observation that valve stability was drastically improved with the use of external suture annuloplasty [38]. The results of valve reimplantation for a similar cohort of patients, which is a more aggressive repair, were also comparable to ours with the same reasoning [39].

While these clinical data produced most of circumstantial evidence, the only clear proof of the importance of annular diameter is probably a computer simulation study [25]. In this investigation, all other dimensions of the aortic cusp and root were kept constant, and only annular diameter was varied (Fig. 4b). With increasing annular diameter, there was a decrease in eH and coaptation height and ultimately also a central lack of coaptation, i.e., a clear morphologic substrate for a leak. Our own first clinical observations with the use of annuloplasty seem to confirm this simulation, in that annular reduction led to a higher proportion of completely competent aortic valves [40].

The interesting question remaining open is whether there is a lower limit of annular size reduction, provided that it does not induce aortic stenosis. The computer simulation model indicates that there must be an optimal relationship between cusp size and annular diameter since marked annular reduction led to billowing of cusps [24].

Importance of STJ dilation

It has long been observed that dilation of the STJ may lead to aortic regurgitation. In fact, the operation of STJ remodeling and its effectiveness have documented that elimination of STJ dilation can improve or even normalize aortic valve function [5, 41, 42]. However, it is as yet unclear whether this argument applies mainly to tricuspid aortic valves or also to other congenital malformations.

Our own clinical observations indicate that tricuspid aortic valves are particularly prone to decrease their coaptation in the presence of STJ dilation (unpublished data). This tendency has also been confirmed by computer simulation (Fig. 4c) [26]. On the other hand, normal values for the STJ are less well defined than for the annulus. In addition, the effect of STJ dilation is almost certainly related to cusp size. In our opinion, a STJ diameter of more than 30 to 35 mm is too large for tricuspid aortic valves and requires its reduction with supracoronary ascending aortic replacement or external suture STJ plasty. We use both procedures depending on the size of the ascending aorta (≥ 40 mm: ascending aortic replacement, < 40 mm: suture STJ plasty).

In bicuspid aortic valves, the impact of STJ dilation might be dependent on their circumferential commissural orientation, i.e., STJ dilation will probably be more critical for asymmetrical commissural orientation. This could be one of reasons why valve repair more frequently failed in asymmetrical bicuspid aortic valves [37]. In unicuspid aortic valves, STJ dilation may affect valve function least of all.

Integration of dimensions into a comprehensive concept

As time goes on and information piles up, it now appears evident that the normal form and function of the aortic valve is dependent on the appropriate relationship between different geometrical determinants. Most determinants can be easily manipulated by surgeons. Annular or STJ diameter can be reduced by annuloplasty or STJ remodeling. Prolapse—characterized by low eH in the presence of an adequate amount of cusp tissue—can be corrected by plication of the cusp free margin. On the other hand, the amount of cusp tissue—quantified with gH as a surrogate parameter—is more difficult to change. The extension of gH can be achieved with patch augmentation of cusps, but the degeneration of patch material is inevitable. In this context, we have to consider again that normal values and arbitrary cut-offs of gH may differ depending on the characteristics of the individuals; short gH could be accepted for valve repair if it matches patients’ body size and aortic root geometry.

Therefore, it seems reasonable to build a comprehensive repair concept integrating the data obtained by the computer simulation and available additional evidence [8, 11, 12, 21, 22, 24–26]. Practically speaking, gH will determine the predicted values of the remaining cusp and root dimensions for successful aortic valve repair. For its clinical application, it would be useful to have either a computer app or a simple table which help the surgeon to make the necessary detailed decisions. This concept has already been introduced by one group with promising first results [43]. Before such an app or table concept can be applied more widely, it will have to be tested further prospectively.

Conclusion

The accumulated knowledge on aortic valve geometry has drastically changed the area of aortic valve repair and valve-sparing aortic root replacement. For many years, these procedures could be performed only in selected patients and only by a limited number of surgeons who could intuitively generate a near-normal shape of the aortic valve. The systematic application of these geometrical principles does not only have the advantage that a much larger cohort of patients can be treated with aortic valve repair; the performance of these operations is greatly facilitated, which will help much more surgeons to repair the aortic valve in a predictable and reproducible fashion.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Not required.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Taylor WJ, Thrower WB, Black H, Harken DE. The surgical correction of aortic insufficiency by circumclusion. J Thorac Surg. 1958;35:192–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpentier A. Cardiac valve surgery--the "French correction". J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1983;86:323–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duran CG. Reconstructive techniques for rheumatic aortic valve disease. J Card Surg. 1988;3:23–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.1988.tb00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosgrove DM, Rosenkranz ER, Hendren WG, Bartlett JC, Stewart WJ. Valvuloplasty for aortic insufficiency. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;102:571–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frater RW. Aortic valve insufficiency due to aortic dilatation: correction by sinus rim adjustment. Circulation. 1986;74:I136–I142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarsam MA, Yacoub M. Remodeling of the aortic valve anulus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;105:435–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.David TE, Feindel CM. An aortic valve-sparing operation for patients with aortic incompetence and aneurysm of the ascending aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;103:617–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schäfers HJ, Schmied W, Marom G, Aicher D. Cusp height in aortic valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schäfers HJ, Aicher D, Riodionycheva S, et al. Bicuspidization of the unicuspid aortic valve: a new reconstructive approach. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:2012–2018. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson RH. Clinical anatomy of the aortic root. Heart. 2000;84:670–673. doi: 10.1136/heart.84.6.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Kerchove L, Jashari R, Boodhwani M, et al. Surgical anatomy of the aortic root: implication for valve-sparing reimplantation and aortic valve annuloplasty. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khelil N, Sleilaty G, Palladino M, et al. Surgical anatomy of the aortic annulus: landmarks for external annuloplasty in aortic valve repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99:1220–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evangelista A, Flachskampf FA, Erbel R, et al. Echocardiography in aortic diseases: EAE recommendations for clinical practice. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010;11:645–658. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jeq056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duran CM, Gometza B, Shahid M, Al-Halees Z. Treated bovine and autologous pericardium for aortic valve reconstruction. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:S166–S169. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)01030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casselman FP, Gillinov AM, Akhrass R, Kasirajan V, Blackstone EH, Cosgrove DM. Intermediate-term durability of bicuspid aortic valve repair for prolapsing leaflet. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:302–308. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pethig K, Milz A, Hagl C, Harringer W, Haverich A. Aortic valve reimplantation in ascending aortic aneurysm: risk factors for early valve failure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:29–33. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swanson M, Clark RE. Dimensions and geometric relationships of the human aortic valve as a function of pressure. Circ Res. 1974;35:871–882. doi: 10.1161/01.res.35.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunzelman KS, Grande KJ, David TE, Cochran RP, Verrier ED. Aortic root and valve relationships. Impact on surgical repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:162–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schäfers HJ, Aicher D, Langer F, Lausberg HF. Preservation of the bicuspid aortic valve. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:S740–S745. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schäfers HJ, Bierbach B, Aicher D. A new approach to the assessment of aortic cusp geometry. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:436–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bierbach BO, Aicher D, Issa OA, et al. Aortic root and cusp configuration determine aortic valve function. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Kerchove L, Momeni M, Aphram G, et al. Free margin length and coaptation surface area in normal tricuspid aortic valve: an anatomical study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;53:1040–1048. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanoverschelde JL, van Dyck M, Gerber B, et al. The role of echocardiography in aortic valve repair. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;2:65–72. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2012.12.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marom G, Haj-Ali R, Rosenfeld M, Schäfers HJ, Raanani E. Aortic root numeric model: correlation between intraoperative effective height and diastolic coaptation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:303–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marom G, Haj-Ali R, Rosenfeld M, Schäfers HJ, Raanani E. Aortic root numeric model: annulus diameter prediction of effective height and coaptation in post-aortic valve repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:406–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.01.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marom G, Halevi R, Haj-Ali R, Rosenfeld M, Schäfers HJ, Raanani E. Numerical model of the aortic root and valve: optimization of graft size and sinotubular junction to annulus ratio. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:1227–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.le Polain de Waroux JB, Pouleur AC, Goffinet C, et al. Functional anatomy of aortic regurgitation: accuracy, prediction of surgical repairability, and outcome implications of transesophageal echocardiography. Circulation. 2007;116:I264–I269. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.680074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thubrikar MJ, Labrosse MR, Zehr KJ, Robicsek F, Gong GG, Fowler BL. Aortic root dilatation may alter the dimensions of the valve leaflets. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28:850–855. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vollebergh FE, Becker AE. Minor congenital variations of cusp size in tricuspid aortic valves. Possible link with isolated aortic stenosis. Br Heart J. 1977;39:1006–1011. doi: 10.1136/hrt.39.9.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silver MA, Roberts WC. Detailed anatomy of the normally functioning aortic valve in hearts of normal and increased weight. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55:454–461. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90393-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.David TE, David CM, Feindel CM, Manlhiot C. Reimplantation of the aortic valve at 20 years. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.deKerchove L, Mastrobuoni S, Boodhwani M, et al. The role of annular dimension and annuloplasty in tricuspid aortic valve repair. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49:428–437. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lansac E, Di Centa I, Sleilaty G, et al. Remodeling root repair with an external aortic ring annuloplasty. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boraita A, Heras ME, Morales F, et al. Reference Values of Aortic Root in Male and Female White Elite Athletes According to Sport. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e005292. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunihara T, Aicher D, Rodionycheva S, et al. Preoperative aortic root geometry and postoperative cusp configuration primarily determine long-term outcome after valve-preserving aortic root repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:1389–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunihara T, Arimura S, Sata F, Giebels C, Schneider U, Schäfers HJ. Aortic annulus does not dilate over time after aortic root remodeling with or without annuloplasty. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155:885–894. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aicher D, Kunihara T, Abou Issa O, Brittner B, Gräber S, Schäfers HJ. Valve configuration determines long-term results after repair of the bicuspid aortic valve. Circulation. 2011;123:178–185. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.934679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider U, Hofmann C, Aicher D, Takahashi H, Miura Y, Schäfers HJ. Suture Annuloplasty Significantly Improves the Durability of Bicuspid Aortic Valve Repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:504–510. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nawaytou O, Mastrobuoni S, de Kerchove L, Baert J, Boodhwani M, El Khoury G. Deep circumferential annuloplasty as an adjunct to repair regurgitant bicuspid aortic valves with a dilated annulus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156:590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.03.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aicher D, Schneider U, Schmied W, Kunihara T, Tochii M, Schäfers HJ. Early results with annular support in reconstruction of the bicuspid aortic valve. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:S30–S34. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.David TE, Feindel CM, Armstrong S, Maganti M. Replacement of the ascending aorta with reduction of the diameter of the sinotubular junction to treat aortic insufficiency in patients with ascending aortic aneurysm. J ThoracCardiovascSurg. 2007;133:414–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asano M, Kunihara T, Aicher D, El Beyrouti H, Rodionycheva S, Schäfers HJ. Mid-term results after sinutubular junction remodelling with aortic cusp repair. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42:1010–1015. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Komiya T, Shimamoto T, Nonaka M, Matsuo T. Is small cusp size is a limitation for aortic valve repair? Eur J CardiothoracSurg. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]